#'the ethics of care considers the family as the primary sphere in which to understand ethical behavior'

Text

i’ve been thinking a lot about what is so unique and appealing about 80s robin jay’s moral standing that got completely lost in plot later on. and i think a huge part of it is that in a genre so focused on crime-fighting, his motivations and approach don’t focus on the category of crime at all. in fact, he doesn’t seem to believe in any moral dogma; and it’s not motivated by nihilism, but rather his open-heartedness and relational ethical outlook.

we first meet (post-crisis) jay when he is stealing. when confronted about his actions by bruce he’s confident that he didn’t do anything wrong – he’s not apologetic, he doesn’t seem to think that he has morally failed on any account. later on, when confronted by batman again, jay says that he’s no “crook.” at this point, the reader might assume that jay has no concept of wrong-doing, or that stealing is just not one of the deeds that he considers wrong-doing. yet, later on we see jay so intent on stopping ma gunn and her students, refusing to be implicit in their actions. there are, of course, lots of reasons for which we can assume he was against stealing in this specific instance (an authority figure being involved, the target, the motivations, the school itself being an abusive environment etc.), but what we gather is that jay has an extremely strong sense of justice and is committed to moral duty. that's all typical for characters in superhero comics, isn't it? however, what remains distinctive is that this moral duty is not dictated by any dogma – he trusts his moral instincts. this attitude – his distrust toward power structures, confidence in his moral compass, and situational approach, is something that is maintained throughout his robin run. it is also evident in how he evaluates other people – we never see him condemning his parents, for example, and that includes willis, who was a petty criminal. i think from there arises the potential for a rift between bruce and jay that could be, have jay lived, far more utilised in batman comics than it was within his short robin run.

after all, while bruce’s approach is often called a ‘philosophy of love and care,’ he doesn’t ascribe to the ethics of care [eoc] (as defined in modern scholarship btw) in the same way that jay does. ethics of care ‘deny that morality consists in obedience to a universal law’ and focus on the ideals of caring for other people and non-institutionalized justice. bruce, while obviously caring, is still bound by his belief in the legal system and deontological norms. he is benevolent, but he is also ultimately morally committed to the idea of a legal system and thus frames criminals as failing to meet these moral (legal-adjacent) standards (even when he recognizes it is a result of their circumstances). in other words, he might think that a criminal is a good person despite leading a life of crime. meanwhile, for jay there is no despite; jay doesn't think that engaging in crime says anything about a person's moral personality at all. morality, for him, is more of an emotional practice, grounded in empathy and the question of what he can do for people ‘here and now.’ he doesn’t ascribe to maxims nor utilitarian calculations. for jay, in morality, there’s no place for impartiality that bruce believes in; moral decisions are embedded within a net of interpersonal relationships and social structures that cannot be generalised like the law or even a “moral code” does it. it’s all about responsiveness.

to sum up, jay's moral compass is relative and passionate in a way that doesn't fit batman's philosophy. this is mostly because bruce wants to avoid the sort of arbitrariness that seems to guide eoc. also, both for vigilantism, and jay, eoc poses a challenge in the sense that it doesn't create a certain 'intellectualised' distance from both the victims and the perpetrators; there's no proximity in the judgment; it's emotional.

all of this is of course hardly relevant post-2004. there might be minimal space for accommodating some of it within the canon progression (for example, the fact that eoc typically emphasises the responsibility that comes with pre-existing familial relationships and allows for prioritizing them, as well as the flexibility regarding moral deliberations), but the utilitarian framework and the question of stopping the crime vs controlling the underworld is not something that can be easily reconciled with jay’s previous lack of interest in labeling crime.

#fyi i'm ignoring a single panel in which jay says 'evil wins. he chose the life of crime' because i think there's much more nuance to that#as in: choosing a life of crime to deliberately cause harm is a whole another matter#also: inb4 this post is not bruce slander. please do not read it as such#as i said eoc is highly criticised for being arbitrary which is something that bruce seeks to avoid#also ethics of care are highly controversial esp that their early iterations are gender essentialist and ascribe this attitude to women#wow look at me accidentally girl-coding jay#but also on the topic of post-res jay.#it's typically assumed that ethics of care take a family model and extend it into morality as a whole#'the ethics of care considers the family as the primary sphere in which to understand ethical behavior'#so#an over-simplification: you are allowed to care for your family over everything else#re: jay's lack of understanding of bruce's conflict in duty as batman vs father#for jay there's no dilemma. how you conduct yourself in the familial context determines who you are as a person#also if you are interested in eoc feel free to ask because googling will only confuse you...#as a term it's used in many weird ways. but i'm thinking about a general line of thought that evolves into slote's philosophy#look at me giving in and bringing philosophy into comics. sorry. i tried to simplify it as much as possible#i didn't even say anything on criminology and the label and the strain theories.#i'm so brave for not info-dumping#i said even though i just info-dumped#jay.zip#jay.txt#dc#fatal flaw#core texts#robin days

203 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Specific Critique of Our Politics

There is growing sentiment that our current political system is broken & needs fundamental change. This to me is both obvious & necessary, but we need to figure out how to navigate the problem of changing fundamental power structures. Here's what I think is the single most elegant & specific critique of both sides, hopefully in a way that provides the eventual clarity necessary to solve our shared problems together.

Both the right & left, individuals, ideologies & political parties are a mess & frankly embarrassing to participate in, hence the record turnout of this year, is still lackluster in any direct analysis. There is much broken to fix, but starting point is important.

The right needs to recognize a deep failure within its moral & psychological framing of people & events. There is a type of 'moral' double bind social dynamic I despise. 'Holier than thou' is one way to describe this double bind game. Another way to phrase it, popularized by Bret Weinstein, is the Personal Responsibility Votex. It works by framing another person such that all their possible decisions appear to be either direct moral failing, or make them powerless. In a large social dynamic this allows the deceptive public figures who use it to blind their audience to the social & moral critiques applied to them by those attempting to constrain their ruthlessness.

This is a common dynamic used by the establishment on the right against their audience, & I believe one of the social forces driving the right into wildly overblown conspiracy theorizing instead of toward the most effective & elegant criticisms of our current social system provided by conscientious objectors on the left, & 'center'. I want to call it something with an egoic sense, beyond the specific tactics used. "I don't need to pay attention to anyone's worldview & ideas except my own because anyone different from me is either weak or a hypocritical liar."

A good concrete & meaningful example is a situation which my own family is in, & a decision tree I have faced myself. I am a staunch environmentalist, although my perspective is far more nuanced than the common tropes of the popular narratives. #solarpunk & others do a good job of popularizing more generally correct ideals closer to my own.

To the point, my family owns oil properties. Oil is clearly a dysfunctional primary energy source going forward, far beyond carbon dioxide, but deeper into how the industry impacts the world in which we all live. Global politics (war & conflict over who profits from oil), finance (who oils & controls society through oil), transportation (asphalt is oil), plastics, farming (fertilizer is oil), pharmaceuticals (organic chemistry can be oil) are all fields of society deeply disturbed by the power structures of oil.

I don't want to participate in that, but I cannot sell my property. If someone else owns it they will build far more pumps & extract far more oil than I do or ever have, or plan to do. I also would be foolish & insane & counter productive to my goals in their pure form if I took a purist stance & went bankrupt via halting all pumping on my property. I would still loose everything to the ruthless oil magnates, but I would also be incapable of doing any good in the world.

Either I am a hypocrite or too weak to do anything useful or meaningful in the world. The situation is systemically broken. Only legislation that stops oil extraction allows the rational approach of my situation to result in an outcome I can accept as good. Until then my moral duty is best served by pumping oil to invest in environmental causes. Which is an absurd situation to find oneself in, but from a sane perspective there is actually no more moral or correct option available to me. I've considered all possibilities at length.

This is a double bind, that traps me in technical hypocricy as the most morally & ethically optimized stable position I can hold. All other positions make those who would harm the earth more powerful at my expense. This is not my failing, but a tragedy of the wise. Understand this, find & respect people who hold positions similar to mine out of moral duty & necessity, despite the tragic self-contribution to the very process which I find necessary & right to end.

*

The left equally has a grave error.

I find it a laughable failure of the intellectual & media elite of the left do not possess & destribute as common knowledge the game theoretic conclusions ones reaches upon an analysis of our voting system. Plurality Voting or (first past the post) #EndPluralityVoting, is an awful system of selection for solving any democratic problem. You will know it as "Choose One Candidate" on a ballot sheet. This voting method itself, as opposed to any other reason, is the specific direct reason we have a two party system. This is a certain & abject truth, that with depth, is inarguable.

The direct, most elegant & most superb alternative system is called #ApprovalVoting, & it is what you would know on a ballot as "Choose One, Or More, Candidate[s]."

Many social media polling systems have this as an option, always use it, it should be the universal voting process default.

Approval Voting has one challenge that prevents it from being common place across democratic systems, it requires a well crafted Parliamentary system to be used at the political stage above it. The two systems integrate together exceptionally well, for deep, nuanced & powerful technical reasons. Of primary import is that Approval Voting most accurately represents the true values & views of the demos, the people, at the cost of some stability & of having an electoral majority. The Parliamentary system handles greater volitity & also non-majority leadership situations better than other political systems.

This is all clear & obvious to me after analyzing political processes, but because this knowledge does not serve the self interest of collecting power, it is not the well destributed understanding of political systems that it should be.

(I will quickly note the popular alternative voting system of #RCV or ranked choice voting. This is a cludge, I support it as better than plurality voting, because anything is, but the only reason it is the voting method of choice is because it's compatible with our current very broken political system, not because it has any superior qualities to approval Voting. It's complicated and less useful. Approval Voting is superior at every angle of analysis except how easy it is to achieve in our current dysfunctional moment.)

*

The sources of dysfunction that are most are fault for neuroticizing us on whichever side, I lay foremost at the feet of these two problems in our approaches to addressing problems in the political/intellectual sphere.

It is time to start applying ourselves with astute, well rounded & careful analysis of broad human systems using the tools of Game Theory & of evolutionary process analysis, which some might know as market forces.

I could go fard deeper into more problems, ad infinitum in fact, I think & write at length on these topics elsewhere, but posting some thoughts on the dysfunctional mess that is our ongoing political moment is a necessary duty I feel is apt & appropriate here.

Thanks for reading.

Take care & keep your soul.

🌳♂️ Masculine Way of Life!🧔🥊

#Election#2020#Voting#Politics#Economics#Solar punk#environment#Environmentalist#solarpunk#Economy#Eco#cottagecore

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Can I be polyamorous and serve in ministry?

This question has been on my mind, in part, due to a parallel fear drawn from my experiences as a queer person. (And a very idle daydream of going into ministry myself, but I am choosing not to examine that too closely right now.) Something LGBTQ folks hear a lot from churches is that while they’re welcome to attend, they are not welcome to serve. This, among other issues, sets up a toxic and false distinction between ‘normal people’ and SOGI minorities—clean and unclean, worthy and unworthy. For surely all that is required to serve the Lord is a penitent and willing heart, and by gatekeeping in this way you’re not-so-subtly sending a message about who is ‘really’ saved and worthy of entering God’s kingdom.

Here in the Anglican Church (of Canada), I seriously doubt anyone would try to stop me from, say, joining the choir or serving on an altar gilding team, but there does seem to be a distinction in the standards lay servants are held to compared to those of the clergy, which is presumably meant for the greater unity and strength of the church.

The most obvious passage to examine in consideration of this question is 1 Timothy 3:2-13, which details requirements for those aspiring to the priesthood, and in the popular consciousness (drawn from the King James Version) declares that bishops and deacons should be ‘the husband of one wife’. In the NRSV, the translation generally used by the Anglican and Episcopalian Churches, it reads as follows:

2 Now a bishop must be above reproach, married only once, temperate, sensible, respectable, hospitable, an apt teacher, 3 not a drunkard, not violent but gentle, not quarrelsome, and not a lover of money. 4 He must manage his own household well, keeping his children submissive and respectful in every way— 5 for if someone does not know how to manage his own household, how can he take care of God’s church? 6 He must not be a recent convert, or he may be puffed up with conceit and fall into the condemnation of the devil. 7 Moreover, he must be well thought of by outsiders, so that he may not fall into disgrace and the snare of the devil.

8 Deacons likewise must be serious, not double-tongued, not indulging in much wine, not greedy for money; 9 they must hold fast to the mystery of the faith with a clear conscience. 10 And let them first be tested; then, if they prove themselves blameless, let them serve as deacons. 11 Women likewise must be serious, not slanderers, but temperate, faithful in all things. 12 Let deacons be married only once, and let them manage their children and their households well; 13 for those who serve well as deacons gain a good standing for themselves and great boldness in the faith that is in Christ Jesus.

‘Married only once’? Interesting. In the New International Version, however, the bishop is specifically charged to be ‘faithful to his wife’, as is the deacon. WELL. Each of these seems, at least on the surface, to emphasise a similar yet distinct point: the NIV charges clergy against cheating; the NRSV, against remarriage; and the KJV, against plural marriage.

This is fascinating, and telling. We Christians do not want to imagine ourselves to be guided by the social mores of our time, yet as culture shifts, so does our theology, to various extents. Tricky or confusing injunctions ought always to be checked against different translations and an understanding of the law rooted in the love of Christ. It happens from time to time that a pastor is exposed for cheating on his wife, and we hear calls from other evangelicals for grace and forgiveness, often without regard for the healing process—and that’s apart from the question of whether forgiveness and reconciliation ought to be on the table at all.

Socially, polyamory is far less understood and accepted than even cheating. Serial monogamy—the string of monogamous relationships that is most people’s dating and marriage history—is all we have achieved under the ideal of ‘till death do we part’. Everyone recognises that faithfulness in monogamy is hard, perhaps nearly impossible, and cheating is generally considered a normal failing, a mistake that doesn’t necessarily define a person. In secular circles, cheating usually results in the de facto dissolution of the primary relationship, but in many religious communities the marriage vows are prioritised above the health and even safety of the couple, so that cheating and sometimes abuse are not definite grounds for divorce.

[As an aside: Even if we make it clear that polyamory, by virtue of being consensual and open, is not cheating—which is, by definition, the breaking of a relationship agreement—it is often thought that polyamorous people take relationships and commitment less seriously. That is untrue. A polyamory proverb (which I draw directly from the seminal work of Eve Rickert and Franklin Veaux, More Than Two) is that people are more important than relationships. If a relationship is not serving the participants, it is their right and duty to make a change; to transition the relationship to something different or, if necessary, end it. This is why, although I am deeply romantic and desire some form of marriage myself one day, I will not make a promise of till death do we part.]

The context, as always, is important to a complex and nuanced understanding of this injunction. What else does this passage say about requirements for our clergy and how might a practice of polyamory complicate or empower a faithful and conscious fulfilment of these commands?

A leader who is ‘temperate, sensible, respectable, hospitable, an apt teacher, not a drunkard, not violent but gentle, not quarrelsome, and not a lover of money … serious, not double-tongued, not indulging in much wine', would be so whether married to one person or three. Yet any relationship requires work, and a lot of it. That’s magnified when you add more partners to the mix, so as with the decision to have any number of children, new relationships must be undertaken with consideration to time, energy, potential growth of the relationship and any other ways it may impact your life and that of your family. One must ‘manage their household well’, as the passage states. Part of being a good leader in any sphere of life is knowing how much to take on and how to assert healthy boundaries. This is a call for moderation and self-control.

It is argued with surprising frequency that polyamory encourages immoderation and a lack of self-control. Indeed, our society at large (thanks to capitalism and its children, instant gratification and excessive consumption) is surely responsible for any lack of discipline particular to the modern population, and it is generally understood in polyamorous spheres that ‘relationship broke, add more people’ is a surefire way of running your relationships into the ground. Anyone experienced with ethical polyamory understands that you can’t simply date everyone you’re attracted to; for the health of yourself, your partners and your family, you’ve got to nurture and strengthen existing relationships, and understand the limits on your time and energy, before forming new connections.

Leaders in the Anglo/Protestant church are generally expected, where they are married, to provide an upstanding model of Christian marriage, but it has always been prescribed by authoritarian powers, rather than the hearts of the individuals involved, who may feel called to take a path less travelled. This marriage is a relatively modern vision which most often takes the form of a consensually romantic and sexual, lifelong, monogamous contract—a far cry from the Biblical standard of marriage as a political and social function, and which was often polygamous. (Still, contemporary North American purity culture often refers to the woman in a conventional marriage as the ‘helpmeet’ of the man, which is an idea still essentially meant for the social and political benefit of the man and, importantly, the survival of the woman.)

I will write further about the potential for a Christian model of polyamorous relationships, but for now I merely wish to make the point that the gold standard of the day for marriage and relationships has almost never been based in principles of true Christian love. Rather, it is by tradition sexist, economically coercive and prone to enabling all kinds of self-serving vices—further, almost no one is able to get it right. Heartache, repression, frustration and abuse are all too common in the standard, with the possibility of alternatives custom-tailored to the people of God—who are, by virtue of their creation, highly unique individuals with vastly different needs—denied in favour of prescriptive conformity to a one-size-fits-all structure.

I don’t know about you, but that sounds more like Empire than Kingdom, and I want no part of it.

#polyamory#polyamorous#christian#christianity#religion#faith#church#polyam#poly#nonmonogamy#nonmonogamous

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

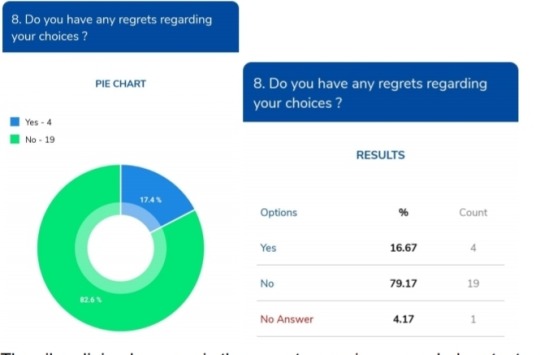

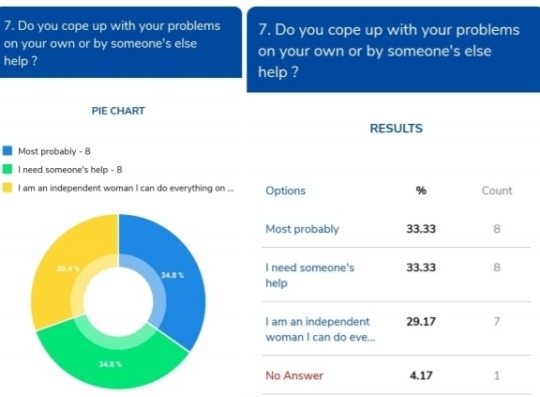

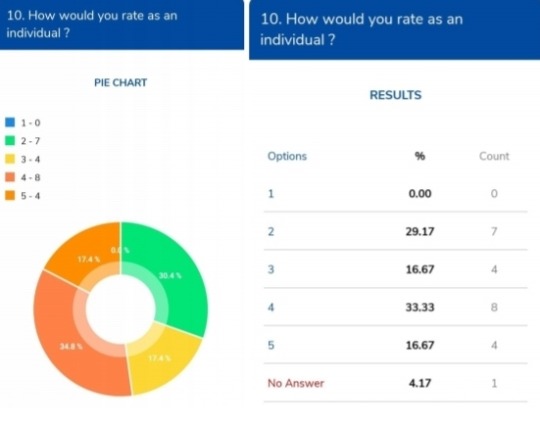

Topic-

Up to what extent women can open up

about their problems they face in the day to day life.

• Women in India have to face a lot of issues. They have to go through gender

discrimination, harassment, sexual abuse, lack of education, dowry-related harassment,

gender pay gap and much more.

• We must come together to empower women. They must be given equal educational

opportunities. Furthermore, they must be paid equally. Moreover, laws must be made more

stringent for crimes against women.

The lack of respect for caregiving Women in the United States who are caregivers—for children, parents, spouses, siblings or

extended family members—have two full-time jobs, while trying to compete with men who

have one. And over half of us are the primary breadwinners in our households. The standard

response is to persuade men to “help” more. But we need a sea-change, one that can

happen only with a normative revolution around the value of care.

Navigating career and motherhood

According to the World Health Organization, 830 women die every day from “preventable

causes related to pregnancy.” These statistics are even more staggering in developing

countries and among women of color in the United States. Black women in particular are the

most affected, dying at a ratio of 25.1 deaths per 100,000.

The economy is not working for women

Women are the primary or joint breadwinners for a majority of American households. But

right now, this economy and our government is not working for them and their families.

Women play a very significant role in the overall development of any society and Kashmir is

no exception. But what is ironic is that despite her equal share in the human development

she remains at the mercy of men at least in our part of the world.

The silver lining however is the recent surge in women led protest movements across India.

She is out there to challenge the well established gender biased norms and deeply

entrenched patriarchal stranglehold over the fairer sex.

Woman is a very strong character than a man as she not only has to take care of herself but

whole family as a daughter, granddaughter, sister, daughter-in-law, wife, mother,

mother-in-law, grandmother, etc. No mean task by any stretch of imagination. Add to this her

role as an active member of the society as a working lady in different spheres of life. Woman

has come of age.

Earlier women in India were facing problems like child marriage, sati pratha, parda pratha,

restriction to widow remarriage, widow exploitation, devadasi system, etc. However, almost

all such old practices have almost vanished. But that doesn’t mean an end to the challenges

women face. New and modern day challenges have cropped up making life uneasy for

women.

Issues facing women still consume the attention of researchers in social sciences,

governments, planning groups, social workers and reformers. Approaches to the study of

women’s problems range from the study of gerontology to psychiatry and criminology. But one important problem relating to women which has been vastly ignored is the problem of

violence against women.

Firstly, violence against women is a very grave issue faced by women in India. It is

happening almost every day in various forms. People turn a blind eye to it instead of doing

something. Domestic violence happens more often than you think. Further, there is also

dowry-related harassment, marital rape, genital mutilation and more.

Next up, we also have the issues of gender discrimination. Women are not considered equal

to men. They face discrimination in almost every place, whether at the workplace or at

home. Even the little girls become a victim of this discrimination. The patriarchy dictates a

woman’s life unjustly.

Moreover, there is also a lack of female education and the gender pay gap. Women in rural

areas are still denied education for being a female. Similarly, women do not get equal pay as

men for doing the same work. On top of that, they also face workplace harassment and

exploitation.

• Not enough women at the table

Kamala Harris is a Democratic U.S. senator from California. She is running for president in

2020.

I don’t think it’s possible to name just one challenge—from the economy to climate change to

criminal justice reform to national security, all issues are women’s issues—but I believe a

key to tackling the challenges we face is ensuring women are at the table, making decisions.

••Trauma-centers

The threat of harm is a human constant, but by any reasonable measure, American women

are among the safest, freest, healthiest, most opportunity-rich women on Earth. In many

ways, we are not just doing as well as men, we are surpassing them. But everywhere,

especially on college campuses, young women are being taught that they are vulnerable,

fragile and in imminent danger. A new trauma-centered feminism has taken hold.

Access to equal opportunity

Education, these mothers believed, would provide their daughters with opportunities they,

because of their gender, were denied. Unfortunately, even with adequate education, women

here in the United States as well as women across much of the world still lack equal access

to opportunity.

Ways to overcome women related issues

1. Raise your voice

Voice amplifies, directs and changes the conversation. Don’t sit silent in meetings or

conversations with friends when you have something to contribute to the conversation.

2. Support one another

Recognize inherent dignity in oneself and all other human beings through acceptance of

identities different from one’s own.

3. Share the workload

Share the responsibility of creating safe environments for vulnerability to be freely

expressed.

4. Get involved

Acknowledge that your actions are crucial to the creation of fairness and accountability.

Identify your commitments. Speak about them, and act on them.

5. Educate the next generation

Listen actively and seek understanding. Share experience and knowledge to grow wisdom.

6. Know your rights

Human rights are women’s rights, and women’s rights are human rights. At their most basic,

human rights concern reciprocity in human relationships that extend to all humanity and

beyond.

7. Join the online conversation

Human beings express their identities and their aspirations through what they say. Join the

IWD Conversation #TimeIsNow and #IWD2018. Social media amplifies women’s voices and

emboldens their collective agency.

8. Give to the cause

It takes time and effort for the gender equality conversation to reach everyone. Consider

giving to the cause by donating money or time

In short we can say that following steps helps in achieving our goal:

Enabling the political empowerment of women

Uplifting the role of women in society through entrepreneurship. Educating

women.Contributing to the education and skills development of women.

Education and skills development is one of the most important

and sustainable interventions needed to effectively assist women

in restoring their lives and positively influencing the future of young

girls.

Developing women as entrepreneurs and mentoring them.

Businesses operating internationally have an ethical responsibility to contribute to the empowerment of people, so that they at

least live above the breadline. Multinational companies are better

positioned to mobilize greater resources in the form of financial aid, proper governance, project management and expertise to bring

entrepreneurial programmes to women in conflict or post-conflict

regions. However, local companies must also bear some of the

responsibility.

- Pooja

0 notes

Photo

Sanctification of Human Labor - Part 2 - Labor Day: USA

Professional Ethics and Sanctification of Work

In this study we will discuss how the message of sanctification of work, spread among persons of all walks of life by St. Josemaría, the founder of Opus Dei, helps clarify many of the central questions of professional ethics in the contemporary world.

St. Josemaría summed up this message as follows: “Those who want to live their faith fully and do apostolate according to the spirit of Opus Dei, must sanctify themselves with their work, sanctify their work, and sanctify others through their work.”

Sanctifying professional work

Beginning with the second of these three points, work is the primary and permanent material that the ordinary Christian has to sanctify. The founder of Opus Dei speaks of “ordinary work,” but he usually made the term more precise by adding the adjective “professional.”

Certainly, the ordinary duties of the Christian cannot be reduced to what would today be called professional work by a sociologist. Work is an essential element in the constitution of civil society, but it cannot “be reduced to its professional dimension, but rather transcends this restricted sphere. . .We can think of the work duties of the mother of a family who devotes herself to domestic tasks and the education of her children on a full-time basis.”

Thus even though “a reduction in the number of hours of work may continue in the future, as history has shown from the beginning of the industrial revolution until today, the message of Opus Dei will continue to exist in a permanent and ever timely way.” St. Josemaría’s concept of work “places before us a primary anthropological concept, with a permanent philosophical meaning.”

The term “professional” has acquired progressive importance throughout the past century. In his encyclical Mater et Magistra (part 2), Pope John XXIII, described the professionalization of human tasks as a phenomenon according to which one placed greater confidence in the income and rights obtained through work than in those derived from capital. One might say that if nineteenth century society was centered on owners and the proletariat, the twentieth century was centered on the professional. Along these lines Pierpaolo Donati observes that the kind of work that is emerging in today’s society is to a large extent made up of relationships. This web of personal relationships in work facilitates the sanctification of tasks, which are thus made more properly human.

The moral code of every profession includes the obligation to carry out a work that is well done. This basic ethical imperative to work well becomes, for the person trying to sanctify his work, an ideal of perfection, since to sanctify something means in the first place to make of it an offering to God. “It is no good offering to God something that is less perfect than our poor human limitations permit. The work that we offer must be without blemish and it must be done as carefully as possible, even in its smallest details, for God will not accept shoddy workmanship.” “If you consider the many compliments paid to Jesus by those who witnessed his life, you will find one which in a way embraces all of them. I am thinking of the spontaneous exclamation of wonder and enthusiasm which arose from the crowd at the astonishing sight of his miracles: bene omnia fecit (Mk 7:37), he has done everything exceedingly well: not only the great miracles, but also the little everyday things that didn’t dazzle anyone, but which Christ performed with the accomplishment of one who is perfectus Deus, perfectus homo, perfect God and perfect man.” Thus our service to God is not true service if “we don’t put as much effort and self-sacrifice as others do into the fulfillment of professional commitments; if we can be called careless, unreliable, frivolous, disorganized, lazy, or useless.”

The ethical imperative to carry out a work that is well done has, for Josemaría Escrivá, ultimately a divine origin, because “work is a command from God.” “After two thousand years, we have reminded all humanity that man was created to work :homo nascitur ad laborem, et avis ad volatum(Job 5:7), man was born to work, and the bird to fly.”

Because of the moral decay that has occurred in our time in many professional practices, it is becoming ever more necessary to clearly explain the basic moral rules that are a condition sine qua non for a particular activity to be qualified as professional. Thereby one can help clarify that immoral behavior, for example, lying, falsifying the evidence supporting a hypothesis, or presenting as one’s own someone else’s ideas, cannot be part of the demands of a profession. These ways of acting are not “professional.” What is more, if they are permitted, one could say that the activity is “de-professionalized.”

Anyone seeking to sanctify his work should consider it indispensable to maintain and strengthen the consistency between his profession and morality. Work, besides being a way of supporting oneself and one’s family, is for St. Josemaría, “an opportunity to develop one’s personality.” Pope John Paul II gives great importance to this quality of work throughout his encyclical Laborem Exercens: “Work is a good thing for man—a good thing for his humanity—because through work, man not only transforms nature, adapting it to his own needs, but he also achieves fulfillment as a human being, and indeed in a sense becomes ‘more a human being.’”

This effort entails a great respect for each one’s personal freedom. One should strive to live one’s faith while respecting and trying to understand the points of view and choices of one’s colleagues. In this respect the teaching of the founder of Opus Dei is clear: “Avoid an abuse that seems to be exaggerated in our times...which shows the desire, contrary to the licit freedom of mankind, to try to oblige all men and women to form a single group in regard to matters of opinion, to create as it were dogmas in temporal questions.”

Finishing tasks well

The ethical importance of professional work being well-done is indisputable. But someone might ask: What do you mean in this context by “work that is well done?” What are the criteria by which one can judge about “professional” goodness in carrying out a task?

It is not enough to consider the opinion of others, although it would be imprudent to ignore this. First of all, for a task to be well done it has to be finished and not left half done. As the founder of Opus Dei said: “You asked me what you could offer God. I don’t have to think twice about the answer: offer the same things as before, but do them better, finishing them with love.”

As the social scientist Peter Drucker has said felicitously, to do good one first has to do something well. This play on words recalls one used much earlier by St. Josemaría: para servir, servir: if you want to be useful, serve. In order to perform a service, to benefit others, one has to serve: to know how to do things, to be useful. “As the motto of your work, I can give you this one: ‘If you want to be useful, serve.’ For, in the first place, in order to do things properly, you must know how to do them. I cannot see the integrity of a person who does not strive to attain professional skills and to carry out properly the task entrusted to his care. It’s not enough to want to do good; we must know how to do it.”

If sanctity is found in the heroic exercise of the virtues, “heroism at work is found in finishing each task.” In many of his writings, St. Josemaría emphasized the requirement to finishing tasks well with italics or even exclamation points. Such emphasis is very understandable if one takes into account that the Christian concept of sanctity implies the “fullness of charity.” This fullness has as its necessary corollary fulfilling as perfectly as possible one’s particular professional duties. It is perhaps here that one can see most graphically the consequences for professional ethics when the person performing a task takes as his goal not merely to fulfill certain minimal ethical rules, but to achieve the fullness of Christian life all his actions.

Care in the details

The importance of finishing work well for it to be perfect, and hence suitable material for the attainment of sanctity—“Be perfect as my heavenly Father is perfect —is closely related to another basic idea in the message of St. Josemaría: putting care into little things, into details. Speaking of his apostolic work in the early years of Opus Dei, he said: “I liked to climb up into the cathedral tower, to look closely at the stonework, a real lacework of stone, the fruit of costly labor.” He would point out that this marvelous craftsmanship could not be seen from below: “That is working for God, the work of God! To fulfill one’s personal task with perfection, with beauty, with the loveliness of that delicate stone tracery.”

This teaching of Josemaría Escrivá is reflected in our ordinary language when we speak, for example, of putting the finishing touches on a building. In fact, today material objects are appreciated and given greater value precisely on the basis of such finishing touches.

Ordinary work

St. Josemaria’s emphasis on the importance of details is well suited to those at whom his message is aimed: ordinary Christians called to sanctify their ordinary work. Sanctity is identified not with extraordinary actions but with a life in which, as the founder of Opus Dei repeatedly said, one does ordinary things extraordinarily well. “It is very much our mission to transform the prose of this life into poetry, into heroic verse.”

Another quality of work that St. Josemaría emphasizes is the need for cheerfulness. “Msgr. Escrivá, with Gospel in hand, constantly taught: God does not want us simply to be good; he wants us to be saints, through and through. However, he wants us to attain that sanctity, not by doing extraordinary things, but rather through ordinary common activities. It is the way they are done which must be uncommon. There in the middle of the street, in the office, in the factory, we can be holy, provided we do our job competently, for love of God and cheerfully, so that everyday work becomes, not ‘a daily tragedy,’ but ‘a daily smile.’”

Finally, the ethical requirement of working well necessarily entails the obligation, also ethical, of continuous education, even more necessary today because of the accelerated advance of science and technology.

Duties of justice in one’s work

The ethical imperative of work that is well done is explicitly related to duties of justice. The “exact fulfillment of one’s obligations” is the best means at hand for a Christian to contribute what he owes to society, making a positive impact on it and ordering it in accord with Christian ends. “While Christians enjoy the fullest freedom in finding and applying various solutions to these problems, they should be united in having one and the same desire to serve mankind.” This is not just a question of a human service to society, but also the effort to ensure that temporal institutions and structures “are in accordance with the principles which govern a Christian view of life.”

St. Josemaría Escrivá founded Opus Dei by divine will as a path of sanctification in professional work and in the fulfillment of the ordinary duties of the Christian. Its faithful to strive to live this message in the midst of the activities of the world. In these activities, each one works and moves “with the full rights of a citizen,” and thus carries out a beneficial influence on the real Christianization of temporal structures from within, at their very source and origin. Therefore exemplarity in the exercise of one’s profession contributes “to the sanctification of the world, as from within like leaven.” Many years prior to the Second Vatican Council, Josemaría Escrivá taught that involvement in the world and intimacy with God were perfectly compatible. This way of fostering the Christianization of the world brings with it “a concern to perfect this world” and to “improve the ordering of human society;” while at the same time contributing to its “temporal progress.” This ordering is “of vital concern to the kingdom of God,” as one reads in the pastoral constitution on the Church in the modern world.

The ordering of human society to God is brought about, according to Gaudium et Spes, through work: “Individual and collective activity, that monumental effort of man through the centuries to improve the circumstances of the world, presents no problem to believers: considered in itself, it corresponds to the plan of God.”

Sanctifying oneself in professional work

One’s particular profession or job represents the material that has to be sanctified, but in addition and simultaneously, it is the means by which one can attain sanctity. Professional work that is well done contributes positively to the growth of the spiritual life in many ways. In first place, work is an indispensable means for the development of the natural virtues, which are the foundation for the supernatural ones.

Work, for the founder of opus Dei, is undoubtedly “a chance to develop one’s own personality” and “to draw fruit from the few or many talents God has given to each person,” and is thus a “witness to the worth of the human creature.” This perfecting of the person who is working goes hand in hand with the reality that is being perfected through one’s work, as Pope John Paul II has stressed. Employing the concepts objective work and subjective work developed in his encyclical Laborem Exercens, he stresses the need both to sanctify work and to sanctify oneself in that work.

One can say that the first and most basic contribution of the Christian to society is to Christianize the world by means of his own work, which constitutes his most noble mission: “Work is a participation in the creative work of God,” who upon creating and blessing man gave him dominion over the earth and all of its creatures. In this context John Paul II wrote: “As man, through his work, becomes more and more the master of the earth, and as he confirms his dominion over the visible world, again through his work, he nevertheless remains in every case and at every phase of this process within the Creator’s original ordering.”

Priestly soul

Work is the privileged milieu for Christians to exercise the supernatural virtues: “to live their faith perfectly,” to engage in “filial contemplation, in a constant dialogue with God,” converting their ordinary activities into an “encounter with God,” into “constant opportunities of meeting God, and of praising him and glorifying him through our intellectual or manual work.”

St. Josemaría emphasizes the intimate relationship between work as a means of sanctification and the priestly soul that every Christian has by reason of baptism, which confers the common priesthood that all the faithful possess. “Acting in this way, in the presence of God, for reasons of love and of service, with a priestly soul, all our actions take on a true supernatural meaning, which keeps our life united to the fount of all graces.” So much so that we can become “contemplative souls in the midst of the world.” Hence our work cannot be done haphazardly or left half-finished, since then it would not be in harmony with the practical requirements of our “priestly soul.”

The common priesthood of the faithful is united, without being confused, with the ministerial priesthood in the sacrifice of the Mass, where the natural elements cultivated by man (the bread and the wine) are converted into the Body and Blood of Christ. As St. Josemaría taught, the worktable of a Christian can be considered as an altar of offerings to God. Since all Christians are “priests of our lives,” and since work constitutes an essential element of human dignity, by offering our work to God at Mass we offer him our entire lives.

Synthesis of the finis operis and the finis operantis

The consideration of work as the material we are called to sanctify and the environment for seeking sanctity constitutes, in our judgment, one of the most important contributions of the founder of Opus Dei.

In human work “sometimes the end of the worker differs from the end of the work.” In ethical considerations of human work there have been those who identify or superimpose both ends, so that the one who carries out the work cannot have any end other than the institutional or objective end of the work itself—as in the case of some socialist interpretations of human work. Others see a complete divorce between the subjective ends of the worker and the objective ends of the work, in what could be called “paleoliberalism.” Here the selfish aim of the individual can be enough to produce a good work, that is, something which is socially useful.

St. Josemaría Escrivá points out the danger of a double life. We can’t have a split personality if we want to be Christians, because “we discover the invisible God in the most visible and material things.” Objective work, visible and material, cannot be indifferent to the life of a Christian, since it “is a participation in the creative work of God.” In addition, work has been taken up by Christ “as something both redeemed and redeeming,” and made into “a means, a way of holiness, a specific task which sanctifies and can be sanctified.”

But the moral goodness of the work done—which should be carried out, as we have said, with the greatest possible human perfection—is assured and increased by the supernatural intention with which it is carried out. The intention has always been important in Christian ethics to attain moral rectitude in one’s actions, which are judged good if they are soex toto genere suo, in all their aspects. Josemaría Escrivá never stopped stressing that a job poorly done cannot be offered to God. But now we can add that the intention of offering it to God is the fundamental incentive for a Christian to do a good job.

An upright finis operantis, a right intention, is not limited then to merely human goals: “feeding one’s self-esteem,” “assuring peace of mind,” or being concerned about what people will say. “First of all you should worry about what God will say: then, very much in the second place, and sometimes not at all, you may consider what others might think.” In line with this, Antonio Aranda has stated from a theological perspective: “Sanctified work (in its double dimension, objective and subjective, that is to say as a work done and the intended action in doing it, both in Christ), has a meaning of its own: it means something in itself and by itself; it is something substantive and not only accidental or instrumental in the plane of the economy of salvation, that is, in the mystery of Christ…Sanctified work (in its objective and subjective dimension) is the essential internal moment of that dynamism of sanctification, and not simple an external or accidental framework or instrument for carrying it out.”

In addition, rectitude of intention leads us to remain vigilant so that professional successes or failures do not make us forget, “even for a moment,” what the true aim of our work is: “the glory of God.” The desire to attain sanctity in our work even leads us to give up, if the Kingdom of God requires this, goals that in themselves are good and licit: “Being a Christian means rising above petty objectives of personal prestige and ambition and even possibly nobler aims, like philanthropy…It means setting our mind and heart on reaching the fullness of love which Jesus Christ showed by dying for us.” This is so because “being a Christian is not something incidental; it is a divine reality that takes root deep in our life. It gives us a clear vision and strengthens our will to act as God wants.”

Striving for rectitude of intention is part of the continuous ascetical effort a zeal for holiness brings with it. Although this is a totally supernatural endeavor, it leads us to fulfill faithfully the natural and even material demands entailed in any human work. Thus the divine reality of the Christian vocation to sanctity is deeply immersed in the realities of our human life. As St. Josemaría said forcefully, “the Christian is no expatriate. He is a citizen of the city of men, while his soul longs for God.”

Sanctifying others through one’s profession

Work, besides being the environment for our sanctification, is also converted into an “instrument” of apostolate. This is both an ethical requirement implied in every profession or job and a consequence of our priestly soul, stemming from the common priesthood of the faithful.

“Our Lord wants men and women of his own in all walks of life. Some he calls away from society, asking them to give up involvement in the world, so that they remind the rest of us by their example that God exists. To others he entrusts the priestly ministry. But he wants the vast majority to stay right where they are, in all earthly occupations in which they work: the factory, the laboratory, the farm, the trades, the streets of the big cities and the trails of the mountains.”

The ethical requirements that human work entails are stressed clearly in the papal encyclicals on social questions: Rerum Novarum,Quadragesimo Anno,Populorum Progessio,Centesimus Annus, and specifically in this case, Laborem Exercens. Evident in all of them is a concern for the state of man the midst of the ever more complex realities of industrial society.

Human development through work

Work can never be allowed to become more important than the persons carrying out the work. To use the terminology employed by John Paul II, objective work can never be allowed to supercede subjective work. Men and women have to be helped to grow as persons while engaged in producing products or performing services. Fostering this human development is undoubtedly part of the apostolate we are called to carry out.

“The apostolic concern which burns in the heart of ordinary Christians is not something separate from their everyday work. It is part and parcel of one’s work, which becomes a source of opportunities for meeting Christ. As we work at our job, side by side with our colleagues, friends and relatives and sharing their interests, we can help them come closer to Christ.” An apostolate of this kind, aside from its clear personal character, rests firmly on the value of human freedom, which our Lord does not destroy. “That is why he does not want to wring obedience from us. He wants our decisions to come from the depths of our heart.”

It would be a simplistic reduction to think that the problem of human development in work is restricted to mere worker-owner relationships, as if the directors, owners or executives of organizations were the only ones responsible for solving the problem. On the contrary, human development is attained through relationships with one’s colleagues, subordinates and superiors, providers and clients, patients and students… In the network of connections through which contemporary work has developed (which In Mater et Magistra is called socialization), the expansion of our anthropological possibilities is many sided and multi-dimensional and is conditioned in all directions.

The “socialization” of work means that no one can carry it out by himself. Professional ethics makes a mistake if it thinks that each individual, although having work relationships with others, is in reality isolated. A fundamental principal of the ethics of work consists in seeing to it that “individuals” grow as “persons” in their relationships with other men and women.

Supernatural development through work

In affirming that work is a means for helping other men and women attain sanctity, we confront the need to foster their development in all aspects. Consequently, apostolate cannot be absent in work, nor should it be considered as an accidental juxtaposition.

For St. Josemaría “professional work is also an apostolate, an opportunity to give ourselves to others, to reveal Christ to them and lead them to God the Father—all of which is the overflow of the charity which the Holy Spirit pours into our hearts. When St. Paul explained to the Ephesians how their conversion to Christianity should affect their lives, one of the things he said was: ‘Anyone who was a thief must stop stealing; he should try to find some useful manual work instead and be able to do some good by helping others that are in need’ (Eph 4:28).”

In addition to being an ethical requirement, sanctification of others through work arises, we might say, as a consequence of the “priestly soul” of the ordinary faithful. The real and effective ordering of temporal structures to the ends foreseen by God — the “effort to build up the earthly city” —is not an individualistic task, carried out atomically or in isolation by each individual: it is a social task. Hence the ordering of temporal structures is not only impossible without apostolate, but constitutes part of the apostolate itself.

The associative character of work and apostolate

Sanctifying others in daily work requires, in the first place, being conscious of the social value of work. St. Josemaría points to the consequences of a certain type of individualism: “If you occupy a position of responsibility, you should remember as you do your job that personal achievement perishes with the person who made himself indispensable.” The need for dividing up work and delegating responsibility, makes it even more indispensable to “work side by side with our companions, sharing their interests.”

Studies of industrial psychology have made it clear that the required division of functions has to be complemented by the coordination of efforts. This double aspect of work is not foreign to its ethical dimensions. “In our ordinary work, we have to always foster an ordered charity, the desire and reality of making our task perfect by love. We have to strive to get along with all men and women, in order to bring them ‘in season and out of season’ (2Tim 4:2), with God’s help and with human refinement, to Christian life, and even to Christian perfection in the world.” This social character of work becomes evident when one considers its purpose as service to the social community: “That is one of the battles of peace we have to win: to find God in our work and, with Him and like Him, serve others.”

Work ethics and Christian asceticism

The recognition of the associative character of work has important consequences for the moral behavior of the worker, fighting against overly individualistic tendencies in one’s work. For example, overcoming the rivalries, suspicions and envies that can easily arise, the tendency to belittle the importance of the work of others, mistrust, disparaging one’s subordinates, etc.

A deep moral effort is required to tear down the barriers between people that impede the carrying out of joint work. This ethical effort can be focused not only from a Christian vision of man but also from a purely natural and professional perspective on work. From this perspective it has been said, and rightly so, that work is the best therapy for selfishness. According to Fritz Schumacher, traditional wisdom teaches us that the basic function of work is simply to give a person the possibility of developing his faculties, of producing the goods and services that we all need for a dignified life, “permitting a person to overcome his innate egocentrism by uniting with other men and women in a common task.”

This requires shared purposes and the interrelationship of efforts, which facilitates apostolate. “The apostolic concern . . . is not something separate from their everyday work. It is part and parcel of one’s work, which becomes a source of opportunities for meeting Christ.” St. Josemaría anticipated the Second Vatican Council’s teaching on the intrinsic nobility of human work: “Moreover, we believe by faith that through the homage of work offered to God man is associated with the redemptive work of Jesus Christ, whose labor with his hands at Nazareth greatly ennobled the dignity of work.”

Work relationships result in the apostolate of an ordinary citizen becoming “a great work of teaching. Through real, personal, loyal friendship, you create in others a hunger for God.” The practice of the virtues that work favors, as we have seen, leads to apostolate. “In fact it already is apostolate. For when people try to live in this way in the middle of their daily work, their Christian behavior becomes good example, witness, something which is a real and effective help to others. They learn to follow in the footsteps of Christ, who ‘began to do and to teach’ (Acts1:1), joining example to word. That is why, for these past forty years, I have been calling this apostolate an ‘apostolate of friendship and confidence.’”

Thus work groups become true communities of persons among whom there arises a mutual enrichment, in place of the mutual impoverishment which results when work is detached from the moral values by which it is intrinsically constituted.

Every kind of work brings with it a social praxis, a tradition, a collective context with ethical and religious implications. It is significant that no current book of “management” fails to emphasize transparency, honesty in presentations, sincerity in leadership, and truth in advertising. Mutual trust constitutes what has become known as “social capital,” which is more important than monetary capital. St. Josemaría always opposed the separation of private and social virtues, just as today the separation between private and public morality proclaimed by ideological liberalism is being refuted.

The apostolate of witness and of word

This apostolate of example, of witness, of friendship and trust contributes to the effective spread, from person to person, of the Christian criterion of life: “Through your professional work, which you bring to completion with all the human and supernatural perfection that is possible, you can and should give Christian standards in the places where you carry out your profession or job.”

One can clearly see that this open and logical (we might say inevitable) apostolic way of acting is not the result of a tactic: it is simply naturalness. “Let your lives as Christian men, as Christian women—your salt and your light—flow spontaneously, without anything odd or foolish: always carry with you our spirit of simplicity.” The question remains as to what is the principal content of the apostolic message that the ordinary Christian can transmit in his work. The answer is simple. The principal content of the message is precisely that of sanctifying what one is doing in the very dynamics of one’s activity of working. The ethics of work necessarily includes doing good to the persons with whom we are working, for whom we are working, under the direction of whom we are working… But for those who are eager to sanctify their work, this ethical imperative leads to its ultimate consequence: encouraging the others to seek sanctity in that which unites them, in their work.

“We have to remember and remind people around us that we are children of God, who have received the same invitation from our Father as the two brothers in the parable: ‘Son, go and work in my vineyard’ (Mt21:28). I give you my word that if we make a daily effort to see our personal duties in this light, that is, as a divine summons, we will learn to carry them through to completion with the greatest human and supernatural perfection of which we are capable.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Politics is What We Bring to the Everyday

by Robert Schmaltz • 29 June 2017

Politics, simply put involves the systematic ordering of society. It is commonly understood that “politicians” are responsible for politics. After all, politicians in the United States democratically assume representational roles in government.

Taken as professionals, it would seem reasonable to expect politicians to be charged with the duty to earnestly inform the public about the complicated matters that are an essential part of their representational practice. For anyone paying attention, politicians on the whole do not hold to such professional standards.

In many cases, persons in political office do not actually fit the conventional description of a professional. Most are politicians are not experts possessing any specialized knowledge that would benefit the complex cause of balancing immediate and long-term national interests. The majority of representatives in government do not have any knowledge in political science, philosophy, history, or even law. Business makes up the larger part of backgrounds to members of Congress, which does not necessarily translate into proficiency for public service.

As subjects, barring just a few, the majority politicians function without a clearly stated professional code. Everything considered, politicians principally aspire to keeping harmony and coherence with their party and supporters, not to value analysis and critical evaluation. It can hardly be said that they are liable to the public trust in all; however, politicians do maintain a special relationship with those who will support their principal aims.

The majority of work that politicians do remains outside of public view. To an even greater extent, policy work is an insulated sphere. The mystery surrounding those bureaucratic processes along with the concentration of benefits floating the dominant ranks of society, dovetailed with a lack of comprehensive returns to the common good has throughout history perpetuated an attitude of distrust toward government and its body of representatives.

How the public comes to be informed politically results from various forms of social, commercial, and political influence. A primary source for public knowledge on politics is political media. What is unique about our present era is just how sweeping political media has become, the diversity of ways made publicly available for accessing political media, and the many methods to participate in that information economy. What is also unparalleled today, is the immense capacity to manipulate the attitudes and behaviors of persons and groups in the American public.

News media places drama at the center of society; political media places drama at the center of democracy. Across outlets from broadcast, to print, to social media, mainstream to fringe, the predominant form of storytelling elevates the status of conflict in politics.

The arts have long maintained drama as an indispensable ingredient to society. Our political media follows in this manner, crafting the story of law and order in relation to society into a tragic one. Reducing representatives to competitors, victors and losers.

The resonance of news and political media is underpinned by the fact that we do always and truly happen to live in an interesting and stimulating world. Packaging this effectively means fulfilling on the aim to gather an audience.

The skillful thrust of this media reinforces a notion of a thoroughly corrupt and savage world. Society as a tragedy. Done well, politics as tragedy does prompt reactive attitudes. It does not incentivize agency. Quite the opposite, politics as tragedy provides incentive to public resignation.

To accept politics as it is presented, is to assume that politics comes down from above and likely has very little to do with us, the overlooked and disenchanted public. The received notion is that outside a narrow range of activities such as voting or protesting - both are essential to civil discourse and democratic order - we in the public do not have political power.

This could not be further from the truth. Politics is not the exclusive domain of corporate and government bodies. Politics is foremost reflected in the practice we bring to the quotidian details of the everyday.

The fulcrum to politics is located in the attitudes and behaviors of the persons and groups that combine together as the public. Not as citizens, but as humans as we are: interdependent and capable of choosing to order our minds, our senses, our lives in such a way that promotes specific living values over others; such as flourishing and inclusion over suffering and alienation. In the methodical ordering of society, the central act is the role each individual consciously accepts or disregards in relation to the concerns for the common good and for each other.

The essential function of politics is as down to earth as the efforts of caring mothers, caring fathers, eager students, life in rural communities, life in urban communities, and those of all variety of workers. Every time a person acts according to a judgement for what is believed to be a shared good, that person is acting politically. This does not assume a universal form of good, but a practical ability to reason, to care, and to guide personal behavior toward affirming the lived experience. Every occurrence like this, of little or large consequence, acts like a stitch in ordering the garment of society.

What each person and group faces politically, requires continuing effort and attention, or practice, of a sensitive kind. Practice is something most of us respect with regard to human excellence in sport. The same kind of practice is required in our daily life, our political life, because to reason personally and interpersonally together about the common good is synonymous with the willingness to be and act political.

As persons, we first receive our understanding of society from those who to varying degrees care for us. As we mature we begin to take on a willing sense of agency even as we continue to be impressed upon. Whether we are aware of the effects that our actions may have or oblivious to those effects, the balance of goods we share in society are sustained and advanced by the degree of practical reasoning we bring to our most basic activities; from how we speak to our children, our friends, and our neighbors as well as how organize, rally, and choose to vote.

People love, suffer, help others, and hurt others just as they will feel the loss of love, receive comfort, and will hurt others. People have needs and they have interests. We bring and raise kids into the world. We seek to improve our self. We stay curious. We get jobs. We get sick. We cry, we celebrate. We live and we die, leaving family and friends to continue on into the future.

All of that matters, and it matters to politics. How we choose to value these parts of our natural lives and relate these parts to our social lives does shape the order of society.

A personal mind turned toward the interdependence of one to each other, acknowledging dependence as counterpart to independence is how a community acts politically. There is no practical top down approach to this. The realistic approach is horizontal.

The actions that order society by and large follow from the attitudes and behaviors of we the persons of the public. How we gather knowledge, freedom of choice, and emotions into ethics or principles that guide our actions, proceeds from a process of acknowledging the absolute interdependent nature of personal growth and social wellness.

The problems that plague the United States today have resulted from a history of public life moving without a common recognition for interdepend needs and deliberation. This, and the receding away from the principle of holding above our other material concerns the common concern for justice and dignity.

We have run the public with a surplus of investment into the value of our corporeal utility, while running a deficit in appreciation for human dignity. With dignity, we expressly recognize what matters to us as humans, and with dignity we act to sustain that which humanly matters most.

The institutions of government, the vertical forms of law and order maintain a legitimate role in performing an irrevocable service to the overall balance and direction of society. These are not the totality of politics. The totality of politics reflects the public’s understanding and appreciation for the social, economic, and political structures of the nation as it relates to personal and interpersonal standards in perception and behavior.

In reality, society has not yet achieved anything like a political ideal. It is sensible that we continue to expect more public service out of elected officials. Also, it is sensible that we continue to seek to know more of what is actually happening in government, from our political media.

But for the aim bringing about politics serving the public good, ordering society into a more just and peaceful form, it is only reasonable to seek more attention to dignity in our own attitudes and behaviors.

_

Image: Annie Albers, With Verticals (1946), cotton and linen 154.9 × 118.1 cm. (Detail)

1 note

·

View note