#1905 russian revolution

Text

On Soviets

"The word “soviet” roughly translates as “council.” These workers councils were first formed during the 1905 Revolution to coordinate strikes among workers and broker deals with factory owners. They were seen as a direct embodiment of proletarian power. This association became important to legitimacy of the St. Petersburg soviet after the tsarist regime fell in 1917 and was later used by the Bolsheviks to define the Soviet Union as a workers' state."

Source: Russian History: from Lenin to Putin (Lecture). University of California, Santa Cruz.

#Soviets#Russian History#Bolsheviks#Bolshevik Party#1905 Russian Revolution#1917 Russian Revolution#The Russian Revolution#the Soviet Union

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

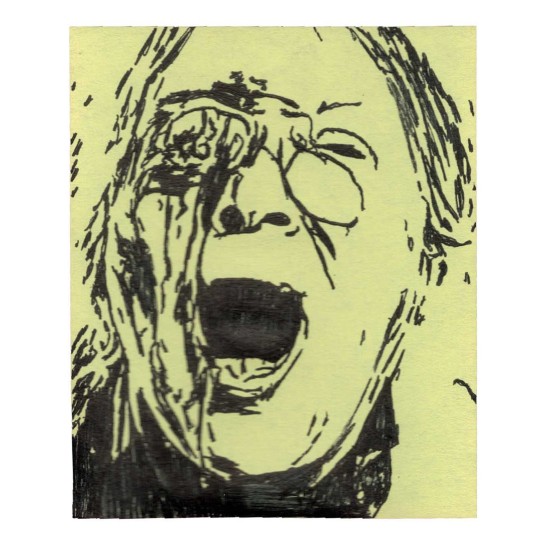

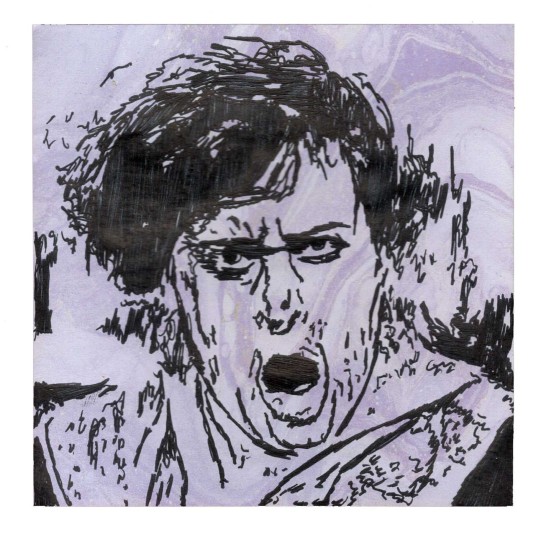

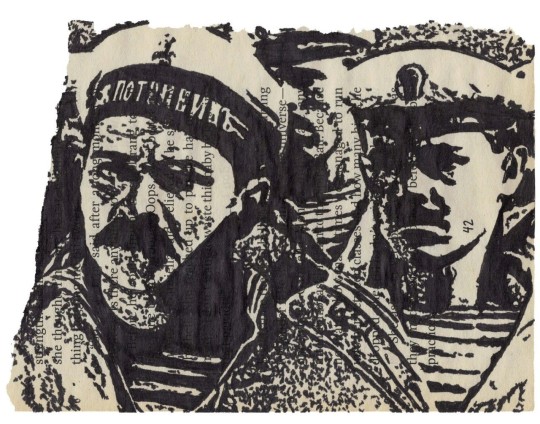

On January 30, 1989 Battleship Potemkin was screened at the Gothenburg Film Festival.

#battleship potemkin 1925#battleship potemkin#sergei eisenstein#soviet film#war films#anti war film#communist propaganda#soviet propaganda#soviet cinema#soviet culture#avant garde film#1905 russian revolution#ussr#soviet movie#movie art#art#drawing#movie history#pop art#modern art#pop surrealism#cult movies#portrait#cult film

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Disarmament Or Disczarmament?

July 31, 1906

The Russian Army holds a gun to the Czar's head, the Douma's Appeal to Army discarded by his boot.

The caption reads "The Czar - ‘If I had only carried out that disarmament idea of mine.’"

The Russian Duma had appealed to the Russian Army to join the revolution against the Czar and his government.

See Also: Nicholas II

From Hennepin County Library

Original available at: https://digitalcollections.hclib.org/digital/collection/Bart/id/5714/rec/207

0 notes

Text

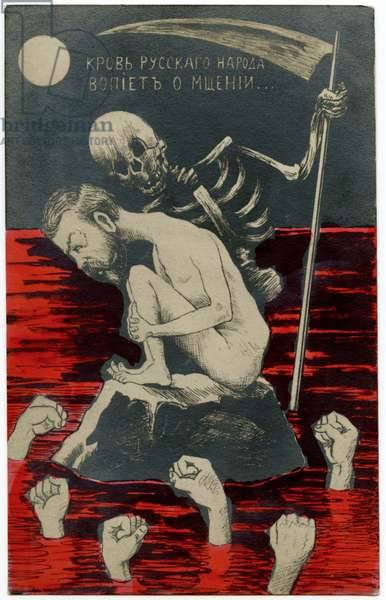

1905 Russian Postcard

The caption in Russian reads: "The Blood of the Russian People Cries Out for Revenge." This is a Russian copy of a French postcard. This dates from the period after the "Bloody Sunday" revolution of 1905, when czarist palace guards shot at protesting crowds, forever burying the Czar's reputation to his people.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The hall of mirrors that Vladimir Putin has built around himself and within his country is so complex, and so multilayered, that on the eve of a genuine insurrection in Russia, I doubt very much if the Russian president himself believed it could be real.

Certainly the rest of us still can’t know, less than a day after this mutiny began, the true motives of the key players, and especially not of the central figure, Yevgeny Prigozhin, the leader of the Wagner mercenary group. Prigozhin, whose fighters have taken part in brutal conflicts all over Africa and the Middle East—in Syria, Sudan, Libya, the Central African Republic—claims to command 25,000 men in Ukraine. In a statement yesterday afternoon, he accused the Russian army of killing “an enormous amount” of his mercenaries in a bombing raid on his base. Then he called for an armed rebellion, vowing to topple Russian military leaders.

Prigozhin has been lobbing insults at Russia’s military leadership for many weeks, mocking Sergei Shoigu, the Russian minister of defense, as lazy, and describing the chief of the general staff as prone to “paranoid tantrums.” Yesterday, he broke with the official narrative and directly blamed them, and their oligarch friends, for launching the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Ukraine did not provoke Russia on February 24, he said: Instead, Russian elites had been pillaging the territories of the Donbas they’ve occupied since 2014, and became greedy for more. His message was clear: The Russian military launched a pointless war, ran it incompetently, and killed tens of thousands of Russian soldiers unnecessarily.

The “evil brought by the military leadership of the country must be stopped,” Prigozhin declared. He warned the Russian generals not to resist: “Everyone who will try to resist, we will consider them a danger and destroy them immediately, including any checkpoints on our way. And any aviation we see above our heads.” The snarling theatricality of Prigozhin’s statement, the baroque language, the very notion that 25,000 mercenaries were going to remove the commanders of the Russian army during an active war—all of that immediately led many to ask: Is this for real?

Up until the moment it started, when actual Wagner vehicles were spotted on the road from Ukraine to Rostov, a Russian city a couple of miles from the border (and actual Wagner soldiers were spotted buying coffee in a Rostov fast-food restaurant formerly known as McDonald’s), it seemed impossible. But once they appeared in the city—once Prigozhin posted a video of himself in the courtyard of the Southern Military District headquarters in Rostov—and once they seemed poised to take control of Voronezh, a city between Rostov and Moscow, theories began to multiply.

Maybe Prigozhin is collaborating with the Ukrainians, and this is all an elaborate plot to end the war. Maybe the Russian army really had been trying to put an end to Prigozhin’s operations, depriving his soldiers of weapons and ammunition. Maybe this is Prigozhin’s way of fighting not just for his job but for his life. Maybe Prigozhin, a convicted thief who lives by the moral code of Russia’s professional criminal caste, just feels dissed by the Russian military leadership and wants respect. And maybe, just maybe, he has good reason to believe that some Russian soldiers are willing to join him.

Because Russia no longer has anything resembling “mainstream media”—there is only state propaganda, plus some media in exile—we have no good sources of information right now. All of us now live in a world of information chaos, but this is a more profound sort of vacuum, because so many people are pretending to say things they don’t believe. To understand what is going on (or to guess at it), you have to follow a series of unreliable Russian Telegram accounts, or else read the Western and Ukrainian open-source intelligence bloggers who are reliable but farther from the action: @wartranslated, who captions Russian and Ukrainian video in English, for example; or Aric Toler (@arictoler), of Bellingcat, and Christo Grozev (@christogrozev), formerly of Bellingcat, the investigative group that pioneered the use of open-source intelligence. Grozev has enhanced credibility because he said the Wagner group was preparing a coup many months ago. (This morning, I spoke with him and told him he was vindicated. “Yes,” he said, “I am.”)

But the Kremlin may not have very good information either. Only a month ago, Putin was praising Prigozhin and Wagner for the “liberation” of Bakhmut, in eastern Ukraine, after one of the longest, most drawn-out battles in modern military history. Today’s insurrection was, by contrast, better planned and executed: Bakhmut took nearly 11 months, but Prigozihin got to Rostov and Voronezh in less than 11 hours, helped along by commanders and soldiers who appeared to be waiting for him to arrive.

Now military vehicles are moving around Moscow, apparently putting into force “Operation Fortress,” a plan to defend the headquarters of the security services. One Russian military blogger claimed that units of the military, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the FSB security service, and others had already been put on a counterterrorism alert in Moscow very early Thursday morning, supposedly in preparation for a Ukrainian terrorist attack. Perhaps that was what the Kremlin wanted its supporters to think—though the source of the blogger’s claim is not yet clear.

But the unavoidable clashes at play—Putin’s clash with reality, as well as Putin’s clash with Prigozhin—are now coming to a head. Prigozhin has demanded that Shoigu, the defense minister, come to see him in Rostov, which the Wagner boss must know is impossible. Putin has responded by denouncing Prigozhin, though not by name: “Exorbitant ambitions and personal interests have led to treason,” Putin said in an address to the nation this morning. A Telegram channel that is believed to represent Wagner has responded: “Soon we will have a new president.” Whether or not that account is really Wagner, some Russian security leaders are acting as if it is, and are declaring their loyalty to Putin. In a slow, unfocused sort of way, Russia is sliding into what can only be described as a civil war.

If you are surprised, maybe you shouldn’t be. For months—years, really—Putin has blamed all of his country’s troubles on outsiders: America, Europe, NATO. He concealed the weaknesses of his country and its army behind a facade of bluster, arrogance, and appeals to a phony “white Christian nationalism” for foreign audiences, and appeals to imperialist patriotism for domestic consumption. Now he is facing a movement that lives according to the true values of the modern Russian military, and indeed of modern Russia.

Prigozhin is cynical, brutal, and violent. He and his men are motivated by money and self-interest. They are angry at the corruption of the top brass, the bad equipment provided to them, the incredible number of lives wasted. They aren’t Christian, and they don’t care about Peter the Great. Prigozhin is offering them a psychologically comfortable explanation for their current predicament: They failed to defeat Ukraine because they were betrayed by their leaders.

There are some precedents for this moment. In 1905, the Russian fleet’s disastrous performance in a war with Japan helped inspire a failed revolution. In 1917, angry soldiers came home from World War I and launched another, more famous revolution. Putin alluded to that moment in his brief television appearance this morning. At that moment, he said, “arguments behind the army’s back turned out to be the greatest catastrophe, [leading to] destruction of the army and the state, loss of huge territories, resulting in a tragedy and a civil war.” What he did not mention was that up until the moment he left power, Czar Nicholas II was having tea with his wife, writing banal notes in his diary, and imagining that the ordinary Russian peasants loved him and would always take his side. He was wrong.

#current events#history#politics#russian politics#russo-ukrainian war#2022 russian invasion of ukraine#russian revolution of 1905#russian revolution#russia#yevgeny prigozhin#vladimir putin#wagner group

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Soviets

'The workers, naturally enough, were the first to react to Bloody Sunday. Abandoning any hope of support from church or tsar, they turned for advice and organizational support to the opposition, especially to the socialists. The Social Democrats and Socialist Revolutionaries were slow to respond: their leaders were still in emigration, cut off from their potential constituents and preoccupied by heated polemics with one another. Local activists did what they could to improvise meetings, protests, and strikes, and gradually their contact with the workers improved and assumed more organized forms.

The result was a new type of workers' association, the Soviet (Council) of Workers' Deputies. First set up in the textile town of Ivanovo-Voznesensk to coordinate a general strike, the soviets were usually elected by the workers of the major enterprises in any given town, at the rate of one deputy for every 500 or so workers. They would meet in a large building, or even in the open air, where not only deputies but also their electors could attend and contribute to discussions. This was a close approach to direct democracy, since, at least in principle, any deputy could be recalled at any time if he failed to satisfy his constituents and be replaced by someone else. The members of each soviet elected an executive committee to deal with day-to-day business and to negotiate with employers, municipality, and police: often they would choose professional people, seeing them as more skillful spokesmen than they themselves could be. Through the executive committees the socialist activists gained influence over the soviets and sometimes directly organized them.

The soviets were the best forum for radical intellectuals and workers to cooperate with each other at a time of political crisis. For the workers, they took a familiar form: their general meetings resembled overgrown and disorderly village assemblies, in which everyone tried to speak and mass enthusiasm welled up. On the other hand, the executive committees supplied the element of conscious policy and organization. The soviets' greatest moment came in St. Petersburg in October 1905, when they organized a general strike which disrupted normal production and communications not only in the capital city but over much of the empire. This was the decisive blow which compelled the tsar to grant the October Manifesto, promising civil liberties and an elected legislative assembly.'

Russia and the Russians, by Geoffrey Hosking

#soviets#workers soviets#workers councils#1905 revolution#russian revolution#russian socialism#october manifesto#general strike#direct action#self-organisation#class struggle

0 notes

Text

IM SO BOREEEEEDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD

#dogstar speaking#this resting shit is annoying!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!#but i gotta bc i worked for 2.55 hours this morning and my brain is offline#i think im too tired to read too#since work was. all reading accounts of the 1905 russian revolution.#and next week is the 1917 russian revolution#and brain dont wanna read again!!!!! brain simply tired!!! i have a burgeoning headache!!!!!!

0 notes

Text

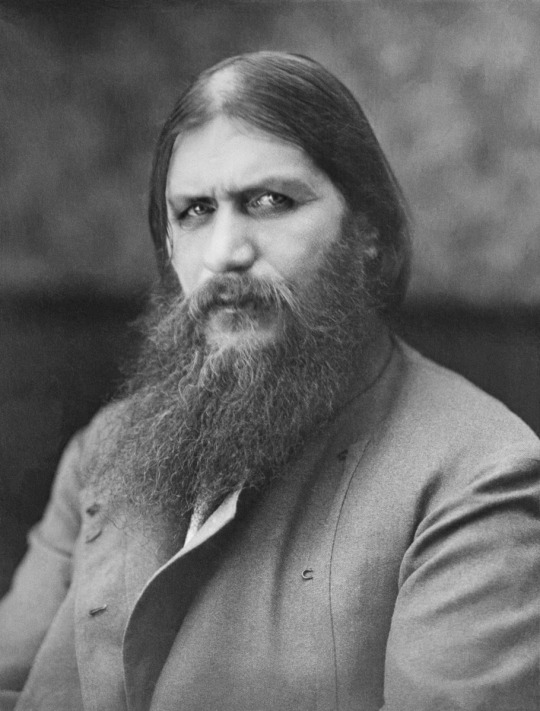

The Uses of History, 22 – Russia the Long-Suffering, 4 – 1905-1914

(Photo credit – Wikipedia – Rasputin)

Following the abortive Revolution of 1905, catalyzed by the defeat in the war with Japan (1904-1905), the Russian Empire clearly needed to undertake serious reform in virtually every aspect of its society. Mere economic reform and modernization of industry and finances would not suffice. There was no imperial will for democracy, but an elected Duma was…

View On WordPress

#Bolsheviks#Duma#Grigori Rasputin#Hemophilia#Kadets#Mensheviks#Russian Revolution#Russian Revolution of 1905#Stolypin#Tsar Nicholas II#Tsarina Alexandra

0 notes

Text

Buffy the Vampire Slayer takes place in a world full of demons and magic and werewolves and invisible girls and convincingly human-like robots; in a world where the Russian Revolution took place in 1905 and a song released in 1957 could be a hit in 1955 and high school sports coaches can use declassified Soviet research to turn teenagers into fish monsters; in a world where vampire attacks are commonplace enough that the police have a standard lie ready to deploy about them and where weekly student deaths are not reason enough to shut down the local high school.

But so far, forty-one episodes into my rewatch, the most fantastic and least plausible thing in the show by some distance is the fact that Buffy still willingly chooses to socialize with Xander Harris.

#btvs#yes it's very boring and obvious to say that Xander sucks and is a terrible friend who is weirdly obsessed about Buffy's sex life#but unfortunately that's the version of the character that the writers consistently put in the show#I genuinely cannot fathom why Buffy lets him talk to her the way he so routinely does#(or what Cordelia is supposed to see in him for that matter)#at this point I am just desperately clinging to the thought that Xander will start to become more tolerable soon

110 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's the justification for the military action against the Kronstadt sailors? From what I understand their demands seem(ed) pretty reasonable

The Russian civil war lasted from right after the October Revolution in 1917 to 1923. The kronstadt rebellion occurred in 1921. It was not a bottom up rebellion like that of the 1905, or Petrograd rebellions. It wasn't sanctioned by the kronstadt soviet, nor did the majority of the ship crews, peasants, and workers support it. It rather had a strange petite-bourgeois mix with 'anarchist' leanings (indeed the case of many anarchist groups). The material effect of the rebellion was, of course, a force of counter-revolution. Even if they did not assist the white army, they did resist the active construction of the Soviet Union and put yet another road bump in the rocky path of the Russian civil war. You can read about what trotsky though about it in hue and cry over kronstadt.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy birthday, Nadezhda Krupskaya! (February 26, 1869)

Wife of Vladimir Lenin and a Marxist revolutionary in her own right, Nadezhda Krupskaya was born to a formerly noble family in Saint Petersburg, and she gained an early sympathy for the plight of the poor. She met Lenin at a Marxist discussion circle in 1894, and they were married in 1898 after he was exiled to Siberia for his revolutionary activities. Like her husband, she was a prominent member of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party, and served as the Central Committee's secretary from 1905. After the Bolshevik Revolution, she was vital to the construction of the Soviet educational system, education having long been a passion of hers. After Lenin's death, Krupskaya continued to play a role in Soviet politics, at times supporting and opposing Stalin's leadership, until her death in 1939.

232 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Opening the Russian Parliament

May 10, 1906

Czar Nicholas carefully opens Russia's New Parliament, unlatching it with a pole, while The Common People and Uncle Sam look on warily.

The caption reads “The Common People - 'What is there in it for me?'

Russia's new parliament, brought on by recent uprisings and protests, was set to open, but Czar Nicholas still maintained an iron grip on power.

See Also: Nicholas II

From Hennepin County Library

Original available at: https://digitalcollections.hclib.org/digital/collection/Bart/id/5694/rec/133

#Charles Bartholomew#political cartoon#1905 russian revolution#russian history#uncle sam#Nicholas II

0 notes

Note

We in the US get like no education whatsoever about Imperial Russian life and culture even in college, what are some things you know about it and whether or not the shift to the Soviet Union and later Russian Federation altered it or killed it?

Apologies if this is a sensitive topic.

Imperial Russia was a whack-ass place, where rughly 85% of the population were peasants, who were not allowed to leave the plot of land they were assigned to. So slaves, with a bit of extra flair.

The rest lived a pretty average European existence of the time, with minor caveats, like the horrible police system, the awful bureaucracy and no political representation whatsoever. Tiny attempts at liberalism were only attempted in the brief time between 1905 and World War I.

Then the Soviets came, tried to do a bunch of wild experiments, before defaulting to the pre-revolution status quo, sans the hereditary monarchy. Like, that's legitimately the only thing they got rid of. Peasants still couldn't leave their villages, there was no political representation and the cities and villages lived in entirely different worlds.

Then the Soviets decided they need HEAVY INDUSTRY and that started a massive growth in the number of urban citizens (a good chunk of which were forcibly-ressetled peasants).

Then the 90s threw everything out of whack. We had a brief period of something approaching political freedom up until roughly 2004, when Putin settled into his autocrat status. The 90s were also, like, really-really bad. Everyone suddenly became even poorer than before and the crime skyrocketed. But there's a good argument to be made that it would've happened anyway, even if USSR didn't collapse. Shit was bad.

Culture-wise all of this did some interesting things. So, in the Imperial times, culture as a whole was a prerogative of the free and the wealthy, but also it was mostly pushed forward by rebellious rich kids in a few big cities. They got a nice formal education, spoke several languages and studied foreign art.

Then the Soviets came and due to the inequality inherent in the Soviet regime, the artists, once again, were relegated to the few big cities where there were education opportunities. But the import of foreign art stopped to a trickle, so the culture diverged from the then-contemporary West in its own weird ways. Ways that were tightly controlled by the state, but hey.

And then in the 90s, 7 lost decades of media suddenly flooded into the country along with true opportunities to rise from nothing for the first time since forever. Again, a very interesting cultural time, until it all got massively corporate and state-sponsored. Yeah, at the same time.

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

Never have I ever game-- you're known for playing with the source material in ways that don't change canon's outcome, but would you ever do a non-canon Black Sails take? An AU that is entirely different setting from pirates, mod au, fairytale au, space au, cowboy au, etc?

Oh that is a great question. I don't generally do AU, and especially not modern AU, because for me personally it is hard to put them into a high enough stakes environment to explore the elements of the show I'm interested in. HOWEVER. There is one that I started to consider a while ago and have pretty thoroughly fleshed out, and have a serious plan to start once other projects are finished, and that is: Russian Revolution AU!

Ok. Stick with me here. [Or don't. I'm going to put this under a cut, it is a lot, and may not make very much sense if you don't already know something about the historical period.]

So, I love the idea of using the Russian revolution as a way to explore some of the same dynamics as the show because it is a period in which there was a lot of righteous idealism, and then it all went very wrong, which naturally brings up questions of ideological commitment vs survival, what are you willing to sacrifice, how do your ideals hold up in the real world, etc. It is also a time when how queerness was treated was very in flux, fitting well with 'we care if its politically convenient to care.'

Basically, we start in the early 1920s right after Lenin dies. Flint is a general, old guard party member, was a commander in the civil war. He is known for doing Really Heinous Flinty Shit during that period. He is sort of revered but also feared, and very ideologically motivated, and so of course he is about to get his ass purged when Stalin starts to consolidate and bring everybody into line.

Silver (10ish years younger) grew up during the upheaval of the 1905, WWI, 1917. He's his survivalist trauma bundle self, and ends up working as a low level NKVD (early Soviet intelligence) guy. He gets sent to keep tabs on/gather evidence against Flint - there is immediately a Frenemies attraction spark there. For Plot Reasons they have to do something together and become Reluctant Allies. I have some of the actual plot worked out but I'm not going to get much into it here, but there is absolutely a parallel conflict in values to the show, and choice that has to be made at the end.

IN THE MEAN TIME interspersed through all of this, in flashbacks: back sometime in the years right after the 1905 revolution, Flint is a promising young military guy who came up from nothing, and has a Hennessey parallel benefactor who sends him to school to be educated. He falls in with Thomas, who is the son of a minor prince, very queer and getting away with it, and is a radical in the Christian anarchist Tolstoy model. Flint gets radicalized through him and his friends, they spend happy years abroad in exile with Thomas writing and Flint being a tactician and doing direct action stuff. They come back in 1917, the civil war starts, Thomas is basically murdered by his family because he sided against them, and he is still set to inherit. SO, that is why Flint goes all Darkness and gets especially nasty during the civil war.

There is a Miranda proxy as well. I believe she disappears and her disappearance is what sets off Plot Events.

It's also set in St. Petersburg, if anybody is wondering. Moscow, with the level I have Flint at, would involve too much interaction with Actual Historical Figures, and while I know a fair amount about this era and am totally committed to research, but still, that gets to be Much.

So, there you have it, Russia AU! My delusional long-term goal is for this to be different enough from canon that it could be published. Thanks for the ask, it's helping me get excited about that project again!

#a lot of the point of Longfic is actually teaching myself to write well enough to do this#ok this is the last one of these i'll throw in the tag i promise#but i can't resist i love this project so much and will take any opportunity to talk about it#anon#black sails#my writing#fanfic#russia au#ask game#spinning shit out on tumblr is so much easier than writing

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

"For the Russians, Alexandra is still the symbol of the secret political adviser. To her credit, a successful personal life. She loved her husband and gave him excellent advice in choosing collaborators: first Sergei Witte, then Pyotr Stolypin. Under her leadership, Russia had an extremely rapid development and a bright cultural life. It was the "Silver Age" in literature, the time of the Symbolists and the first Cubists in painting, Russian ballets in music and dance. The reasons for criticism with regard to her are the two wars, one lost, in 1904, against Japan, the other, which cost many Russian lives, the war of 1914, as well as the revolutions of 1905 and 1917. Many felt that she played a fatal role in the imperial couple and that she did not have the necessary qualities to occupy such important functions. Her physical fragility and introverted temperament did not allow her to play a beneficial political role for Russia in times of crises. But in today's Russia a more favorable image of the last Tsarina begins to impose itself, precisely to the extent that communist ideology evaporates. In the 1970s, it was carried by Samizdat - a "parallel" publication - and even by certain official media. In 1972, the large-circulation daily Zviezda published a detailed and objective account of the assassination of the Tsar and his family, "the twenty-three steps". In 1977, an elegy in memory of the imperial family was published in a Leningrad magazine, Avrora. Nowadays portraits of the Tsarina and her family circulate freely. And the archives also confirm Alexandra's exceptional courage during the captivity."

The Tsarinas - The Women who Made Russia | Vladimir Fedorovski

(loose translation)

77 notes

·

View notes

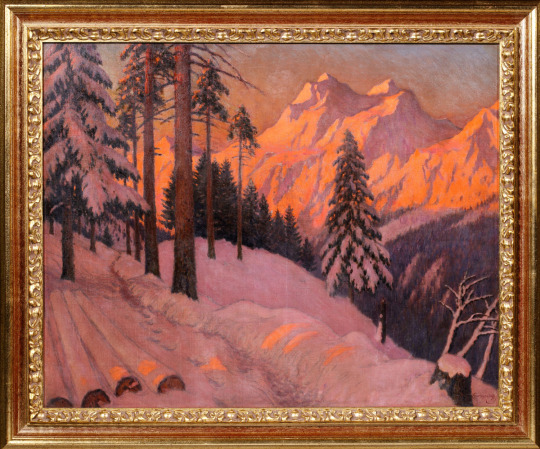

Text

Germashev Mikhail Markianovich (1867-1930).

Sunset in the Mountains

Oil on canvas.

Bottom right: "Guermacheff."

Expert opinion - NINE named after P.M. Tretyakova (2021).

Expert - Yu.V. Chaykina.

Decorated in a frame.

Famous painter, graphic artist. He studied at MUZHVZ (1892-1899) with A.E. Arkhipov, N.A. Kasatkina, I.I. Levitan, K.A. Savitsky and others. In 1897, for the painting "Snow Fell", later acquired by P.M. Tretyakov, he received the prize "for the genre" of the Moscow Society of Art Lovers named after N.S. Mazuryan. He lived in Moscow. He painted landscapes, still lifes, works on genre subjects. He worked in watercolor and pastel techniques. He continued "wandering traditions" in his work. Favorite themes of Germashev's paintings were winter and spring landscapes of Central Russia ("Grey Day", 1894; "The Frozen River", 1898; "In March", 1905; "To Spring", 1912). Since 1892 - participant of exhibitions (apprentice, MUZHVZ). Member and exhibitor of the Moscow Association of Artists (1893-1910, with interruptions), the Moscow Society of Art Lovers (1896-1908, with interruptions), the art circle "Sreda" (Shmarinoff Wednesdays, 1911). He exhibited his works at Spring exhibitions in the halls of the IACH (1898-1900), TPHV (1901-1914, with breaks). In 1911 he traveled to France, in 1915 he visited France and Belgium. After the October Revolution, he participated in the VI Art Exhibition of Paintings by Northern Artists in Vologda, the Exhibition of Paintings, Sculpture and Art Industry in Ryazan (both - 1918), the VIII State Exhibition in Moscow (1919). In the early 1920s, he emigrated and settled in Paris. He painted Russian landscapes under a contract with Marshal Leon Gerard. He was engaged in book illustration. He exhibited his works at exhibitions at the Gerard Gallery, the Salon of the National Society of Fine Arts and the Federation of French Artists (1927). Germashev's works are in many museum and private collections, including the State Russian Museum, the Irkutsk Regional Art Museum named after V.P. Sukacheva and others.

Nikitskiy

20 notes

·

View notes