#West Virginia University Press

Text

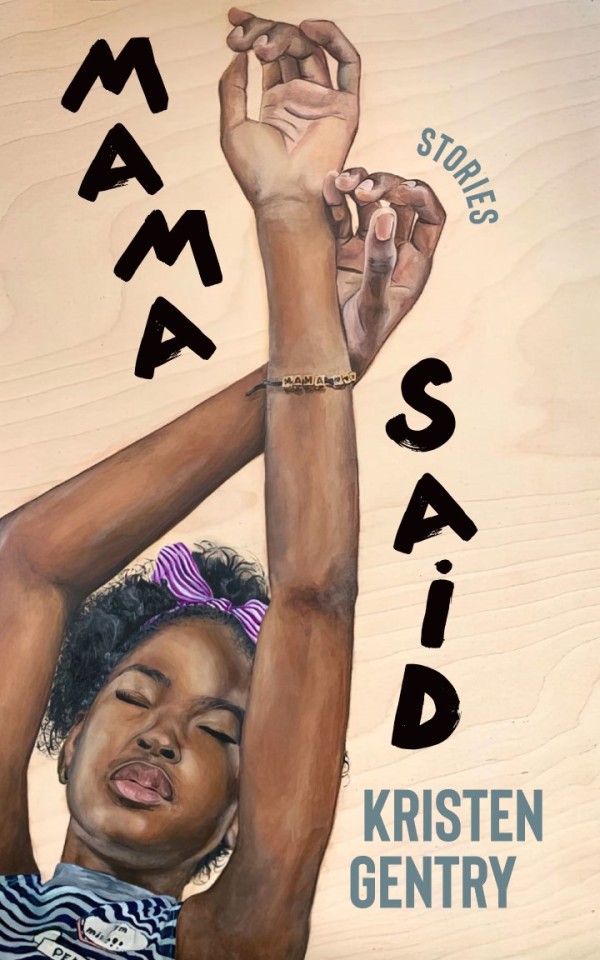

Book Spotlight: MAMA SAID by Kristen Gentry

Today's book spotlight shines on MAMA SAID: STORIES by #KristenGentry, published by #WVUPress. #fiction #shortstories #WestVirginiaUniversityPress

Mama Said: Stories by Kristen GentryISBN: 9781952271984 (Paperback)ISBN: 9781952271991 (eBook)ASIN: B0CDHLY51X (Kindle edition)Page Count: 288Publication Date: October 1, 2023Publisher: West Virginia University PressGenre: Fiction | Short Stories

Original stories of Black family life in Louisville, Kentucky, for readers of Dantiel Moniz (Milk Blood Heat) and Kai Harris (What the Fireflies…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

(Recommended) GOOD OMENS FICS THAT TEACH YOU STUFF

Was inspired by @maaikeatthefullmoon who posted a fic rec list, and I wanted to do something similar.

Because I like to learn while I read. Sometimes I’ll read a fic and had no idea that Things Could Be Like That, and I’m just floored, thinking about it for days, googling and crying. As I haven’t the best memory, I might have forgotten some, and I might add more later. Everything is rated E or M because I only read the slick and sloppy.

THE LIST

1: For Loving One (AU) - World War II has never really interested me, and I didn’t know much about what it was like to be queer back then. I just assumed almost everyone was out to get you (and I wasn’t wrong), but I just didn’t have any reference material. Now I do, as it’s clear the author knows a lot about this topic. This is a beautiful story, well researched, with just enough happy and just enough angst. I’ve learned a lot, entirely without meaning to.

2: Epistolary - one of my favorite tropes, which is Crowley finding and reading Aziraphale’s diary and stumbling upon very private thoughts and YearningTM throughout history. There are plagues, there are Aztec ritual sacrifices, there’s a long-haired, sleeping Crowley in a cave and Aziraphale losing his mind yearning over (literally over) said sleeping Crowley.

3: exodus2 (canon compliant AU - yes, it’s possible) - Ezra and Crowley, programming students in their early 20s, meet at university in a totalitarian European state, and both have an interest in banned media and causing some trouble. You’ll learn some Hebrew, some Yiddish and Scandinavian - and how to start an insurrection against the State. And, there are (banned) book recommendations!

4: A Godawful Small Affair - What if Vince Taylor wasn’t Bowie’s inspiration for Ziggy Stardust? A fic that placed me firmly in a music scene I’ve never immersed myself in, in a decade I somehow skipped over. Yes, I know, I’m weird - but I’ve learned a lot! It’s sweet and it really feels probable.

5: Rough Enough for Love (AU) - As an AFAB person, I’ve learned so much about… uh, the subjective intricacies of AMAB anatomy. Also, it’s nice to skip the yearning sometimes and just read them having their cake and eating it too.

6: The False and the Fair (AU) - I knew nothing about West Virginia, nor about coal mining. It has all the feels and if this was about anyone other than the ineffables I wouldn’t have read it and I would have missed out. I’ve learned so much about a society and a setting so far from everything I thought I was interested in. Don’t miss out!

7: A Gift of Words - Okay, it’s not slick and sloppy - but VERY sweet, and I learned a lot about Gutenberg and the printing press. Crowley changes the world for his angel, by giving him (arguably) his most favorite thing.

—

Let me know if YOU wrote a fic in which you teach the reader about something you have special knowledge of! I’d like to read, learn and link to it.

As a treat: a picture of a peacock because I’m on holiday in Portugal.

And yes, one of my fics is in there. Not ashamed. Hah!

#crowley#ineffable husbands#good omens fandom#good omens 2#aziraphale x crowley#crowley x aziraphale#ineffable spouses#innefable husbands#ineffable divorce#good omens fic recs#good omens fic rec#good omens fanfiction#good omens fanfic rec#good omens au#good omens after dark#good omens inspired#aziracrow

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

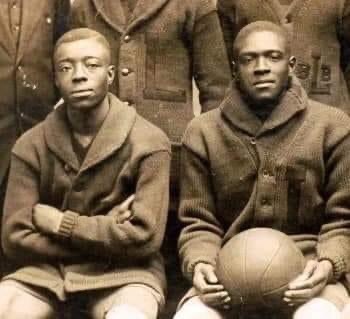

‘Pimp’ and ‘Lyss’: The Immortal Young Brothers by Claude Johnson (Black Fives Foundation)

They were brothers on and off the court. William Pennington Young, sometimes known as “Pimp” to his friends, and his older brother Ulysses S. Young, known simply as “Lyss” to his pals, were an unstoppable sibling pair of African American basketball stars that played during the 1910s and early 1920s.

They also made significant pioneering contributions off the court, long after their playing days ended.

Ulysses was born in Virginia in 1894. A year later, after his hard working parents migrated tot he North in pursuit of a better life, younger brother William was born in Orange, New Jersey.

A few years later, in 1900, their parents rented a room of their home to a young couple from Virginia, the Ricks family, who had a newborn son named James. Over the years the Young brothers embraced little James as if he were their own kin, and as the older boys got involved in sports, so did their protégé.

Something in that combined household created serious athletic skills.

Lyss and William attended nearby Orange High School, where they starred in football, basketball, and baseball. In 1910, while still in high school, the pair began playing semi-pro basketball for the Imperial Athletic Club, a local squad that competed against such teams as the Newark Strollers, the Montclair Athletic Club, and the Jersey City Colored YMCA. The two immediately received attention in the black sports press, including the popular and nationally circulated New York Age.

Their attraction to basketball got young James hooked on the sport too, and he soon developed his own talent. One huge advantage was having the opportunity to learn from- and train with the Young brothers.

The little basketball apprentice, James Ricks, would grow up to become James “Pappy” Ricks, who would become a founding member of the New York Renaissance Big Five professional basketball team and eventually reach the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame.

After high school, the Young brothers attended Lincoln University in West Chester, Pennsylvania, which was not only America’s oldest historically black university but also was the closest to home for them. In college they both were once again three-sport stars. Though the brothers excelled in each sport, their first claim to fame was through football.

Playing quarterback, William was named as a Negro All-American during his senior year. Ulysses, playing end, was named to the Milton Roberts All Time Black College Football Squad for the 1910s Decade.

After graduating from Lincoln (“Pimp” was class valedictorian in 1917), the Youngs were recruited to play professional basketball in Pittsburgh by prominent African American sports promoter Cumberland Posey. Posey, historian Rob Ruck wrote in Sandlot Seasons, his landmark book that explores the city’s unique athletic heritage, “was,as much as any one man could be, the architect of sport in black Pittsburgh.”

The pioneering promoter had been cultivating Pittsburgh’s black basketball talent through his operation of several different squads in the city, most prominently the Monticello Athletic Association, since the early 1910s. But with America’s imminent entry into World War I and the resulting lack of resources, Posey decided to consolidate his best talent into one powerfully built team.

The result was the Loendi Big Five, a legendary combo that was sponsored and got its name from the Loendi Social & Literary Club, an exclusive African American social club in the the city’s predominantly black Hill District.

1921.

Adding the collegiate superstars from Lincoln not only helped Posey promote his new team but also sparked the Loendi Big Five’s domination of black basketball, with a dynasty that included four straight Colored Basketball World Championships from 1919 through 1923.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

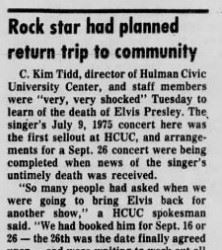

Had history turned out differently, Elvis' work schedule was set to continue throughout the late summer and autumn of 1977. Reports suggest that Elvis was in good spirits in the weeks off following his June tour, and told his cousin, Billy Smith, that this next tour was going to be the best yet.

This is the itinerary for his August tour:

Aug 17 - Cumberland County Civic Center, Portland, Maine

Aug 18 - Cumberland County Civic Center, Portland, Maine

Aug 19 - Utica Memorial Auditorium, Utica, NY

Aug 20 - Onondaga County War Memorial, Syracuse, NY

Aug 21 - Civic Center, Hartford, Connecticut

Aug 22 - Nassau Veterans Coliseum, Uniondale, NY

Aug 23 - University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky

Aug 24 - Roanoke Civic Center, Roanoke, Virginia

Aug 25 - Cumberland County Arena, Fayetteville, NC

Aug 26 - Asheville Civic Center Arena, Asheville, NC

Aug 27 - Mid-South Coliseum, Memphis, Tennessee

Aug 28 - Mid-South Coliseum, Memphis, Tennessee

At the time of his passing, there were already some keenly anticipated dates confirmed for a tour in September.

Sep 21, 1977 - Huntington Civic Center, Huntington, West Virginia

Sep 22, 1977 - Huntington Civic Center, Huntington, West Virginia

Sep 26, 1977 - Indiana State University , Terre Haute, Indiana

Sep 28, 1977 - Savannah Civic Center, Savannah, Georgia

Special thanks to Francesc Lopez for providing information and press for the September tour.

In October, Elvis was due open the 5 000 seat Las Vegas Hilton Pavilion, a new showroom which was part of a major hotel redevelopment.

And then, in September 1978...

#elvis history#elvis presley#elvis in the 70s#elvis fans#rock history#elvis 1970s#elvis aaron presley#musicians#las vegas

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

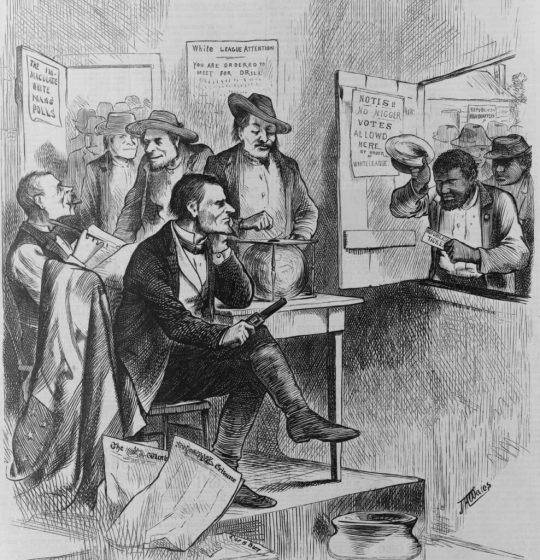

Land taken from African Americans through trickery, violence and murder

For generations, African American families passed down the tales in uneasy whispers: "They stole our land."

These were family secrets shared after the children fell asleep, after neighbors turned down the lamps -- old stories locked in fear and shame.

Some of those whispered bits of oral history, it turns out, are true.

In an 18-month investigation, The Associated Press documented a pattern in which African Americans were cheated out of their land or driven from it through intimidation, violence and even murder.

In some cases, government officials approved the land takings; in others, they took part in them. The earliest occurred before the Civil War; others are being litigated today.

Some of the land taken from African families has become a country club in Virginia, oil fields in Mississippi, a major-league baseball spring training facility in Florida.

The United States has a long history of bitter, often violent land disputes, from claim jumping in the gold fields to range wars in the old West to broken treaties with American Indians. Poor European landowners, too, were sometimes treated unfairly, pressured to sell out at rock-bottom prices by railroads and lumber and mining companies.

The fate of African American landowners has been an overlooked part of this story.

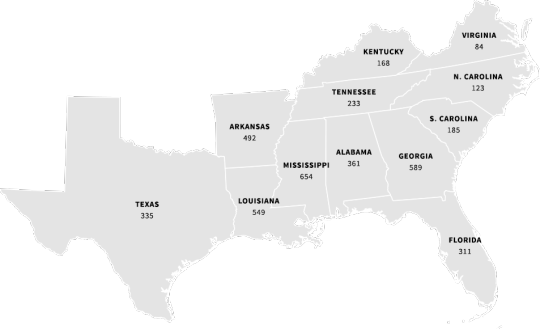

The AP -- in an investigation that included interviews with more than 1,000 people and the examination of tens of thousands of public records in county courthouses and state and federal archives -- documented 107 land takings in 13 Southern and border states.

In those cases alone, 406 African American landowners lost more than 24,000 acres of farm and timber land plus 85 smaller properties, including stores and city lots. Today, virtually all of this property, valued at tens of millions of dollars, is owned by Europeans or by corporations.

Properties taken from Africans were often small -- a 40-acre farm, a general store, a modest house. But the losses were devastating to families struggling to overcome the legacy of slavery. In the agrarian South, landownership was the ladder to respect and prosperity -- the means to building economic security and passing wealth on to the next generation. When African American families lost their land, they lost all of this.

"When they steal your land, they steal your future," said Stephanie Hagans, 40, of Atlanta, who has been researching how her great-grandmother, Ablow Weddington Stewart, lost 35 acres in Matthews, N.C. A European lawyer foreclosed on Stewart in 1942 after he refused to allow her to finish paying off a $540 debt, witnesses told the AP.

"How different would our lives be," Hagans asked, "if we'd had the opportunities, the pride that land brings?"

No one knows how many African American families have been unfairly stripped of their land, but there are indications of extensive loss.

Besides the 107 cases the AP documented, reporters found evidence of scores of other land takings that could not be fully verified because of gaps or inconsistencies in the public record. Thousands of additional reports of land takings from African American families remain uninvestigated.

Two thousand have been collected in recent years by the Penn Center on St. Helena Island, S.C., an educational institution established for freed slaves during the Civil War. The Land Loss Prevention Project, a group of lawyers in Durham, N.C., who represent blacks in land disputes, said it receives new reports daily. And Heather Gray of the Federation of Southern Cooperatives in Atlanta said her organization has "file cabinets full of complaints."

AP's findings "are just the tip of one of the biggest crimes of this country's history," said Ray Winbush, director of Fisk University's Institute of Race Relations.

Some examples of land takings documented by the AP:

After midnight on Oct. 4, 1908, 50 hooded European men surrounded the home of a African farmer in Hickman, Ky., and ordered him to come out for a whipping. When David Walker refused and shot at them instead, the mob poured coal oil on his house and set it afire, according to contemporary newspaper accounts. Pleading for mercy, Walker ran out the front door, followed by four screaming children and his wife, carrying a baby in her arms. The mob shot them all, wounding three children and killing the others. Walker's oldest son never escaped the burning house. No one was ever charged with the killings, and the surviving children were deprived of the farm their father died defending. Land records show that Walker's 2 1/2-acre farm was simply folded into the property of a white neighbor. The neighbor soon sold it to another man, whose daughter owns the undeveloped land today.In the 1950s and 1960s, a Chevrolet dealer in Holmes County, Miss., acquired hundreds of acres from African American farmers by foreclosing on small loans for farm equipment and pickup trucks. Norman Weathersby, then the only dealer in the area, required the farmers to put up their land as security for the loans, county residents who dealt with him said. And the equipment he sold them, they said, often broke down shortly thereafter. Weathersby's friend, William E. Strider, ran the local Farmers Home Administration -- the credit lifeline for many Southern farmers. Area residents, including Erma Russell, 81, said Strider, now dead, was often slow in releasing farm operating loans to Africans. When cash-poor farmers missed payments owed to Weathersby, he took their land. The AP documented eight cases in which Weathersby acquired African-owned farms this way. When he died in 1973, he left more than 700 acres of this land to his family, according to estate papers, deeds and court records.In 1964, the state of Alabama sued Lemon Williams and Lawrence Hudson, claiming the cousins had no right to two 40-acre farms their family had worked in Sweet Water, Ala., for nearly a century. The land, officials contended, belonged to the state. Circuit Judge Emmett F. Hildreth urged the state to drop its suit, declaring it would result in "a severe injustice." But when the state refused, saying it wanted income from timber on the land, the judge ruled against the family. Today, the land lies empty; the state recently opened some of it to logging. The state's internal memos and letters on the case are peppered with references to the family's race.

In the same courthouse where the case was heard, the AP located deeds and tax records documenting that the family had owned the land since an ancestor bought the property on Jan. 3, 1874. Surviving records also show the family paid property taxes on the farms from the mid-1950s until the land was taken.

AP reporters tracked the land cases by reviewing deeds, mortgages, tax records, estate papers, court proceedings, surveyor maps, oil and gas leases, marriage records, census listings, birth records, death certificates and Freedmen's Bureau archives. Additional documents, including FBI files and Farmers Home Administration records, were obtained through the Freedom of Information Act.

The AP interviewed black families that lost land, as well as lawyers, title searchers, historians, appraisers, genealogists, surveyors, land activists, and local, state and federal officials.

The AP also talked to current owners of the land, nearly all of whom acquired the properties years after the land takings occurred. Most said they knew little about the history of their land. When told about it, most expressed regret.

Weathersby's son, John, 62, who now runs the dealership in Indianola, Miss., said he had little direct knowledge about his father's business affairs. However, he said he was sure his father never would have sold defective vehicles and that he always treated people fairly.

Alabama Gov. Don Siegelman examined the state's files on the Sweet Water case after an inquiry from the AP. He said he found them "disturbing" and has asked the state attorney general to review the matter.

"What I have asked the attorney general to do," he said, "is look not only at the letter of the law but at what is fair and right."

The land takings are part of a larger picture -- a 91-year decline in African American landownership in America.

In 1910, African Americans owned more farmland than at any time before or since -- at least 15 million acres. Nearly all of it was in the South, largely in Mississippi, Alabama and the Carolinas, according to the U.S. Agricultural Census. Today, Africans own only 1.1 million of the country's more than 1 billion acres of arable land. They are part owners of another 1.07 million acres.

The number of European American farmers has declined over the last century, too, as economic trends have concentrated land in fewer, often corporate, hands. However, African American ownership has declined 2 1/2 times faster than white ownership, the U.S. Civil Rights Commission noted in a 1982 report, the last comprehensive federal study on the trend.

The decline in African American landownership had a number of causes, including the discriminatory lending practices of the Farmers Home Administration and the migration of Africans from the rural South to industrial centers in the North and West.

However, the land takings also contributed. In the decades between Reconstruction and the civil rights struggle, black families were powerless to prevent them, said Stuart E. Tolnay, a University of Washington sociologist and co-author of a book on lynchings. In an era when African Americans could not drink from the same water fountains as European and African men were lynched for whistling at white women, few Africans dared to challenge Europeans. Those who did could rarely find lawyers to take their cases or judges who would give them a fair hearing.

The Rev. Isaac Simmons was an exception. When his land was taken, he found a lawyer and tried to fight back.

In 1942, his 141-acre farm in Amite County, Miss., was sold for nonpayment of taxes, property records show. The farm, for which his father had paid $302 in 1887, was bought by a European man for $180.

Only partial, tattered tax records for the period exist today in the county courthouse; but they are enough to show that tax payments on at least part of the property were current when the land was taken.

Simmons hired a lawyer in February 1944 and filed suit to get his land back. On March 26, a group of Europeans paid Simmons a visit.

The minister's daughter, Laura Lee Houston, now 74, recently recalled her terror as she stood with her month-old baby in her arms and watched the men drag Simmons away. "I screamed and hollered so loud," she said. "They came toward me and I ran down in the woods."

The Europeans then grabbed Simmons' son, Eldridge, from his house and drove the two men to a lonely road.

"Two of them kept beating me," Eldridge Simmons later told the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. "They kept telling me that my father and I were 'smart niggers' for going to see a lawyer."

Simmons, who has since died, said his captors gave him 10 days to leave town and told his father to start running. Later that day, the minister's body turned up with three gunshot wounds in the back, The McComb Enterprise newspaper reported at the time.

Today, the Simmons land -- thick with timber and used for hunting -- is privately owned and is assessed at $33,660. (Officials assess property for tax purposes, and the valuation is usually less than its market value.)

Over the past 20 years, a handful of African families have sued to regain their ancestral lands. State courts, however, have dismissed their cases on grounds that statutes of limitations had expired.

A group of attorneys led by Harvard University law professor Charles J. Ogletree has been making inquries recently about land takings. The group has announced its intention to file a national class-action lawsuit in pursuit of reparations for slavery and racial discrimination. However, some legal experts say redress for many land takings may not be possible unless laws are changed.

As the acres slipped away, so did treasured pieces of family history -- cabins crafted by a grandfather's hand, family graves in shaded groves.

But "the home place" meant more than just that. Many Africans have found it "very difficult to transfer wealth from one generation to the next," because they had trouble holding onto land, said Paula Giddings, a history professor at Duke University.

The Espy family in Vero Beach, Fla., lost its heritage in 1942, when the U.S. government seized its land through eminent domain to build an airfield. Government agencies frequently take land this way for public purposes under rules that require fair compensation for the owners.

In Vero Beach, however, the Navy appraised the Espys' 147 acres, which included a 30-acre fruit grove, two houses and 40 house lots, at $8,000, according to court records. The Espys sued, and an all-white jury awarded them $13,000. That amounted to one-sixth of the price per acre that the Navy paid European neighbors for similar land with fewer improvements, records show.

After World War II, the Navy gave the airfield to the city of Vero Beach. Ignoring the Espys' plea to buy back their land, the city sold part of it, at $1,500 an acre, to the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1965 as a spring training facility.

In 1999, the former Navy land, with parts of Dodgertown and a municipal airport, was assessed at $6.19 million. Sixty percent of that land once belonged to the Espys. The team sold its property to Indian River County for $10 million in August, according to Craig Callan, a Dodgers official.

The true extent of land takings from African families will never be known because of gaps in property and tax records in many rural Southern counties. The AP found crumbling tax records, deed books with pages torn from them, file folders with documents missing, and records that had been crudely altered.

In Jackson Parish, La., 40 years of moldy, gnawed tax and mortgage records were piled in a cellar behind a roll of Christmas lights and a wooden reindeer. In Yazoo County, Miss., volumes of tax and deed records filled a classroom in an abandoned school, the papers coated with white dust from a falling ceiling. The AP retrieved dozens of documents that custodians said were earmarked for shredders or landfills.

The AP also found that about a third of the county courthouses in Southern and border states have burned -- some more than once -- since the Civil War. Some of the fires were deliberately set.

On the night of Sept. 10, 1932, for example, 15 Europeans torched the courthouse in Paulding, Miss., where property records for the eastern half of Jasper County, then predominantly African, were stored. Records for the predominantly white western half of the county were safe in another courthouse miles away.

The door to the Paulding courthouse's safe, which protected the records, had been locked the night before, the Jasper County News reported at the time. The next morning, the safe was found open, most of the records reduced to ashes.

Suddenly, it was unclear who owned a big piece of eastern Jasper County.

Even before the courthouse fire, landownership in Jasper County was contentious. According to historical accounts, the Ku Klux Klan, resentful that African were buying and profiting from land, had been attacking African-owned farms, burning houses, lynching African farmers and chasing African American landowners away.

The Masonite Corp., a wood products company, was one of the largest landowners in the area. Because most of the land records had been destroyed, the company went to court in December 1937 to clear its title. Masonite believed it owned 9,581 acres and said in court papers that it had been unable to locate anyone with a rival claim to the land.

A month later, the court ruled the company had clear title to the land, which has since yielded millions of dollars in natural gas, timber and oil, according to state records.

From the few property records that remain, the AP was able to document that at least 204.5 of those acres had been acquired by Masonite after African American owners were driven off by the Klan. At least 850,000 barrels of oil have been pumped from this property, according to state oil and gas board records and figures from the Petroleum Technology Transfer Council, an industry group.

Today, the land is owned by International Paper Corp., which acquired Masonite in 1988. Jenny Boardman, a company spokeswoman, said International Paper had been unaware of the "tragic" history of the land and was concerned about AP's findings.

"This is probably part of a much larger, public debate about whether there should be restitution for people who have been harmed in the past," she said. "And by virtue of the fact that we now own these lands, we should be part of that discussion."

Even when Southern courthouses remained standing, mistrust and fear of white authority long kept Africans away from record rooms, where documents often were segregated into "white" and "colored." Many elderly Africans say they still remember how they were snubbed by court clerks, spat upon and even struck.

Today, however, fear and shame have given way to pride. Interest in genealogy among African families is surging, and some African whispered stories.

"People are out there wondering: What ever happened to Grandma's land?" said Loretta Carter Hanes, 75, a retired genealogist. "They knew that their grandparents shed a lot of blood and tears to get it."

Bryan Logan, a 55-year-old sports writer from Washington, D.C., was researching his heritage when he uncovered a connection to 264 acres of riverfront property in Richmond, Va.

Today, the land is Willow Oaks, an almost exclusively European American country club with an assessed value of $2.94 million. But in the 1850s, it was a corn-and-wheat plantation worked by the Howlett slaves -- Logan's ancestors.

Their owner, Thomas Howlett, directed in his will that his 15 slaves be freed, that his plantation be sold and that the slaves receive the proceeds. When he died in 1856, his European relatives challenged the will, but two courts upheld it.

Yet the freed slaves never got a penny.

Benjamin Hatcher, the executor of the estate, simply took over the plantation, court records show. He cleared the timber and mined the stone, providing granite for the Navy and War Department buildings in Washington and the capitol in Richmond, according to records in the National Archives.

When the Civil War ended in 1865, the former slaves complained to the occupying Union Army, which ordered Virginia courts to investigate.

Hatcher testified that he had sold the plantation in 1862 -- apparently to his son, Thomas -- but had not given the proceeds to the former slaves. Instead, court papers show, the proceeds were invested on their behalf in Confederate War Bonds. There is nothing in the public record to suggest the former slaves wanted their money used to support the Southern war effort.

Moreover, the bonds were purchased in the former slaves' names in 1864 -- a dubious investment at best in the fourth year of the war. Within months, Union armies were marching on Atlanta and Richmond, and the bonds were worthless pieces of paper.

The Africans insisted they were never given even that, but in 1871, Virginia's highest court ruled that Hatcher was innocent of wrongdoing and that the former slaves were owed nothing.

The following year, the plantation was broken up and sold at a public auction. Hatcher's son received the proceeds, county records show. In the 1930s, a Richmond businessman cobbled the estate back together; he sold it to Willow Oaks Corp. in 1955 for an unspecified amount.

"I don't hold anything against Willow Oaks," Logan said. "But how Virginia's courts acted, how they allowed the land to be stolen -- it goes against everything America stands for."

#afrakan#african#kemetic dreams#africans#afrakans#european american#european#europeans#land grab#land

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Supreme Court declined on Tuesday to revisit the landmark First Amendment decision in New York Times v. Sullivan, rebuffing a request to take another look at decades-old precedent that created a higher bar for public figures to claim libel in civil suits.

The media world has for years relied on the unanimous decision in the 1964 case to fend off costly defamation lawsuits brought by public figures. The ruling established the requirement that public figures show “actual malice” before they can succeed in a libel dispute.

Despite being a mainstay in US media law, the Sullivan decision has increasingly come under fire by conservatives both inside and outside the court, including Justice Clarence Thomas, who said on Tuesday that he still wanted to revisit Sullivan at some point.

“In an appropriate case, however, we should reconsider New York Times and our other decisions displacing state defamation law,” Thomas wrote in a brief concurrence to the court’s decision not to take up the case. He said that the case, Don Blankenship v. NBC Universal, LLC, was a poor vehicle to reconsider Sullivan.

Just a few months ago, the conservative justice attacked the ruling in Sullivan in a fiery dissent in which he called it “flawed.” Thomas issued other public critiques of Sullivan in recent years, including in 2019, when he wrote that the ruling and “the Court’s decisions extending it were policy-driven decisions masquerading as constitutional law.”

The case at hand concerns Don Blankenship, a former coal baron who was convicted of a federal conspiracy offense related to a deadly 2010 explosion at a mine he ran, in what was one of the worst US mine disasters in decades. His sentence of a year in prison was one day less than a felony sentence.

“Blankenship himself admits this was a highly unusual sentence for a misdemeanor offense; he notes that he was the only inmate at his prison who was not serving a sentence for a felony conviction,” according to a lower-court opinion in the case.

During his unsuccessful 2018 US Senate campaign in West Virginia, a number of media organizations erroneously reported that he was a convicted felon, even though his conspiracy offense was classified as a misdemeanor.

Blankenship sued a slew of news outlets for the error, alleging defamation and false light invasion of privacy. Lower courts ruled against him, finding that the outlets did not make the statements with actual malice, the standard required by Sullivan.

Attorneys for Blankenship told the justices in court papers that the “damage was irreparable” since no felon has ever been elected to the Senate, and urged them to overturn the Sullivan decision.

“The actual malice standard poses a clear and present danger to our democracy,” they wrote. “New York Times Co. v. Sullivan and its progeny grant the press a license to publish defamatory falsehoods that misinform voters, manipulate elections, intensify polarization, and incite unrest.”

Attorneys for the media outlets urged the justices not to take up the case, arguing that it’s “as poor a vehicle as one could imagine to consider” questions related to Sullivan’s holding because, they said, the reporting mistakes were honest ones.

“There is good reason why the actual malice standard of New York Times has been embraced for so long and so often,” the media organizations told the justices. “At its essence, the standard protects ‘erroneous statements honestly made.’ While it permits recovery for falsehoods uttered with knowledge of falsity or with reckless disregard for the truth, it provides the ‘breathing space’ required for ‘free debate.’ A free people engaged in self-government deserves no less.”

Just last year the court declined to revisit Sullivan in a case brought by a not-for-profit Christian ministry against the Southern Poverty Law Center.

At the time, Thomas dissented from the court’s refusal to take up the case.

“I would grant certiorari in this case to revisit the ‘actual malice’ standard,” he wrote. “This case is one of many showing how New York Times and its progeny have allowed media organizations and interest groups ‘to cast false aspersions on public figures with near impunity.’”

In 2021, conservative Justice Neil Gorsuch also questioned the decision in Sullivan, writing in a dissent when the court decided not to take up a defamation case that the 1964 ruling should be revisited in part because it “has come to leave far more people without redress than anyone could have predicted.”

#us politics#news#cnn#justice clarence thomas#us supreme court#New York Times v. Sullivan#first amendment#defamation#actual malice standard#libel#civil lawsuits#Justice Neil Gorsuch#Don Blankenship#2023#Don Blankenship v. NBC Universal LLC

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

What was Lafayette's opinions on slavery? Sorry if this has been asked before ^^

Dear Anon,

excellent question! And please, never be sorry to ask anything. :-) While something like this has already been asked, I needed to update the post anyway.

The short answer is, La Fayette was decidedly opposed to the concept of slavery. But, just like with many white men of influence at that time – the matter was not quite that simple.

La Fayette had his first real exposure to the concept of slavery during his first visit to America. He soon could not quite understand how a people, fighting for Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness could keep other people in bondage. He furthermore witnessed first hand the bravery, ingenuity, cleverness and determination of enslaved people – one notable person here is James Armistead, later James Armistead Lafayette. When the state of Virginia refused to grant James his freedom after the end of the Revolutionary War, La Fayette used the full weight of his name to aide James, who rendered an invaluable service to La Fayette by spying for him on the British. The two men would later meet again during La Fayette’s tour to America 1824/25.

Back home in France with free time on his hand La Fayette wanted actions to follow his words. He wanted to show everybody that it was possible to abolish slavery – gradually at least. He wanted to purchase a plantation and a number of enslaved individuals and then teach them everything they needed to know – in his opinion at least, to be freed. He told Washington (and a number of other people) about his idea and tried to enlist his aide. In general, La Fayette often discussed the matter of slavery with Washington, who owned quite a number of enslaved individuals himself, and even tried to convince him of freeing all these men and women. La Fayette hoped that Washington’s greater than life reputation would convince other people to do so as well. Washington’s reputation and great name were also surely among the reasons why La Fayette wanted his help with regard to his plantation-project. He wrote the following in a letter to Washington on February 5, 1783:

Now, My dear General, that You are Going to Enjoy some Ease and Quiet, Permit me to propose a plan tot you Which Might Become Greatly Beneficial to the Black part of Mankind—Let us Unite in Purchasing a small Estate Where We May try the Experiment to free the Negroes, and Use them only as tenants—Such an Example as Yours Might Render it a General Practice, and if We succeed in America, I Will chearfully devote a part of My time to Render the Method fascionable in the West indias—if it Be a Wild scheme, I Had Rather Be Mad that Way, than to Be thought Wise on the other tack.

“To George Washington from Marie-Joseph-Paul-Yves-Roch-Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette, 5 February 1783,” Founders Online, National Archives, [This is an Early Access document from The Papers of George Washington. It is not an authoritative final version.] (01/25/2023)

For the next three years, not, much was happening – until La Fayette wrote Washington again on July 14, 1785:

You Remember an idea which I imparted to you three years ago—I am Going to try it in the french Colony of Cayenne—But will write more fully on the Subject in my other letters.

“To George Washington from Lafayette, 14 July 1785,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Confederation Series, vol. 3, 19 May 1785 – 31 March 1786, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1994, pp. 120–121.] (01/25/2023)

He wrote again to Washington on February 6, 1786:

(…) an other Secret I intrust to you, my dear General, is that I Have purchased for Hundred And twenty five thousand French livres a plantation in the Colony of Cayenne and am going to free my Negroes in order to Make that Experiment which you know is My Hobby Horse.

“To George Washington from Lafayette, 6 February 1786,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Confederation Series, vol. 3, 19 May 1785 – 31 March 1786, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1994, pp. 538–547.] (01/25/2023)

La Fayette had instructed his attorney to buy property in French Guiana in a letter on June 7, 1785 with the condition that he would “neither sell nor exchange any black.“ The 125.000 Livre he paid translate roughly to 1.250.000 modern US Dollar. The plantation was named La Belle Gabrielle and was the “home” of just under seventy individuals between the ages of a few months and 59 years (I have sadly never seen a more precise number). The Administer of the plantation, a Monsieur de Geneste, send La Fayette a list with the names, ages, and descriptions of these people. Here is the first page of his report.

Intendant L. de Geneste. “List of Negro Slaves Selected by Daniel Lescallier” for Lafayette’s Experimental Plantation. March 1, 1789, La Fayette: Citizen of Two Worlds, Cornell University. (01/25/2023)

La Belle Gabrielle was a clove and cinnamon plantation and after La Fayette bought the property, he employed the following changes. The people there were paid, given free time and days off and an education. Furthermore, the severity of their punishments was toned down to resemble the punishment that any free white labourer would face under similar circumstances. He soon bought additional property because La Belle Gabrielle did not sustain itself, since the production was switched to less labour intensive and less profitable crops. When the French Revolution really hit it off in 1789, La Fayette had less and less time to spend on his “hobby horse” as he called it. His wife Adrienne, who was involved from the begin, took over and managed now most of the plantation’s affairs. Adrienne was a very religious person and the moral and religious education of the people on the plantation was for her of great importance. Shee corresponded regularly with Miolas Jacquemin, a missionary who lived in a settlement of missionaries close by the plantation. It seems as though he not only reported to her what was happening on the plantation but that he and his fellow missionaries also coordinated the religious education of the people there.

In 1792, when the National Convention called for La Fayette’s arrest and he was captured by the Prussians, his properties were sold, including his plantation. His improvements on the plantations were revoked. In February of 1794 the Convention abolished slavery and French Guiana was actually one of the places that was reached by the new law while in many French colonies things continued like they were despite the new law. Furthermore, French Guiana was one of the few places that did not see a lot of violent upheaval during this time – something La Fayette later in life took great comfort in.

Jules Germain Cloquet wrote about this whole endeavour:

But he was not content with sterile wishes; and on his return to France, flattering himself, like Turgot and Poivre, that the gradual emancipation of the negroes might be conciliated with the personal interests of the colonists, he was desirous of establishing the fact by experience, and for that purpose he tried a special experiment, on a scale sufficiently large to put the question to the test. At that period, the intendant of Cayenne was a man of skill, probity, and experience, named Lescalier, whose opinions on the subject coincided with those of Lafayette. Marshal de Castries, the minister of the marine, not only consented to the experiment, but determined to aid it by permitting Lescalier to try upon the king's negroes the scheme for a new system. Lafayette had at first devoted 100,000 francs to this object: he confided the management of the residence which he had purchased at Cayenne to a man distinguished for philosophy and talent named Richeprey, who generously devoted himself to the direction of the experiment. The seminarists established in the colony, and above all the Abbé Farjon, the curate of it applauded and encouraged the measure. It is but justice to the colonists of Cayenne to say, that the negroes had been treated with more humanity there than elsewhere.

Richeprey’s six months’ stay there, and the example set by him before he fell a victim to the climate, contributed still further to assuage their lot. Larochefoucauld was to purchase another plantation as soon as Richeprey’s establishment had met with some success, and a third was afterwards to be bought by Malesherbes, who took a cordial interest in the plan. The untimely death of Richeprey, the difficulty of replacing such a man, the departure of the intendant, and a change in the ministry, threw obstacles in the way of this noble undertaking. When Lafayette had been proscribed in 1792, the National Convention confiscated all his property, and ordered his negroes to be sold at Cayenne, in spite of the remonstrances of Lafayette, who protested against the sale, observing that the negroes had been purchased only to be restored to liberty after their instruction, and not to be again sold as objects of trade and speculation. At a later period, all the negroes of the French colonies were declared free by a decree of the National Convention. It is nevertheless remarkable, that some of Lafayette’s plans with regard to slave emancipation were realized: Cayenne, the only one of our colonies in which the example set by him of instructing the negroes had been followed, was also the only colony in which no disorders took place. Urged by gratitude, the negroes of his plantation declared to Richeprey’s successor that if Lafayette’s property was confiscated they would avail themselves of their liberty, but that in the opposite case they would remain and continue to cultivate his estate. Lafayette was desirous of emancipating the negroes only by degrees and in proportion as their moral intellectual education rendered them worthy of freedom. He foresaw all the inconveniences that might the sudden emancipation of a people debased by slavery, and the dangers that must follow their transition from a state of brutal degradation to one entire liberty, - a state that must prove to them more than one of unbridled licentiousness, of despotism would artfully take advantage, as of a weapon, first to establish, and next to justify sway. For man, in fact, there are moral as well physical transitions. The prisoner enfeebled by a confinement in dark dungeons cannot, without danger, be suddenly restored to the light of day. The slave, like manner is, fitted to enjoy liberty only after enlightenment as to the privileges which it confers, duties which it imposes, and the limits prescribed to by reason and justice. But, in Lafayette’s opinion, the greater the difficulties that impeded the abolition of slavery, the more energetic should be the zeal, the more persevering the efforts, of the genuine to obtain so honourable a result; and he saw with pain that paltry considerations of interest paralysed the hearts of some who might have given a impulse to negro emancipation.

Jules Germain Cloquet, Recollections of the Private Life of General Lafayette, Baldwin and Cradock, London, 1835, pp. 152-154.

Even after this failed project and his personal hardships, he continued to be outspoken. He was a member of several manumission societies and corresponded with abolitionists all around the world. He and his wife Adrienne joined the Society of the Friends of Blacks right when it was founded in 1788. He was unanimously named a member of the Society for the Emancipation of the Blacks. He was also Vice-President of the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America. His last known letter was written to an abolitionist society in Glasgow. Interestingly, one of the few letter we have written by La Fayette to his daughters and daughters-in-law talks about slavery:

(…) there [Florida and Louisiana] is only one point to which I decidedly cannot resign myself: that is slavery, and the anti-Black prejudices. I believe that in this respect my travel might have been useful. The fact that I asked to meet with colored men who fought on January 8 was another proof of what I am preaching continuously, not for the beauty of it, but in order to bring gradual healing.

Lafayette. Letter to his Daughters and Grand-daughters. New Orleans, April 15, 1825, La Fayette: Citizen of Two Worlds, Cornell University. (01/25/2023)

La Fayette was praised and quoted by many abolitionists that came after him, Frederick Douglass quoted letters between George Washington and La Fayette in relation to the plantation in Cayenne in his news paper. Senator Charles Sumner famously quoted a letter by La Fayette to John Adams from February 22, 1786:

(…) in the Cause of My Black Brethren I feel Myself Warmly interested, and Most decidedly Side, so far as Respects them, Against the White part of Mankind— Whatever Be the Complexion of the Enslaved, it does not, in my opinion, Alter the Complexion of the Crime Which the Enslaver Commits, a Crime Much Blaker than Any Affrican face— it is to me a Matter of Great Anxiety and Concern to find that this trade is Some times perpetrated under the flag of liberty, our dear and Noble Stripes, to which Virtue and Glory Have Been Constant Standard Bearers—

“To John Adams from the Marquis de Lafayette, 22 February 1786,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Adams Papers, Papers of John Adams, vol. 18, December 1785–January 1787, ed. Gregg L. Lint, Sara Martin, C. James Taylor, Sara Georgini, Hobson Woodward, Sara B. Sikes, Amanda M. Norton. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016, pp. 182–183.] (01/25/2023)

Most notable is perhaps this quote from La Fayette:

Digital Commonwealth: Massachusetts Collections Online, Boston Public Library, Anti-Slavery (Collection of Distinction) (01/25/2023)

I would never have drawn my sword in the cause of America, if I could have conceived that thereby I was founding a land of slavery.

The British abolitionist Thomas Clarkson claimed that La Fayette wrote the above quote in a letter to him. This quote was printed on broadsides as seen above and distributed in America, mainly in New England I think. While it can be debated if La Fayette really said it like this, the publication of the broadsides had an enormous impact.

We could conclude the matter here and agree that La Fayette really meant well, he was opposed to slavery and earnestly wanted to do something. Were all of his believes as enlightened as he might have wanted them to be? Definitely not! Could some of his measures have been more thoughtful, more effective - in simple term “better”? Certainly! But La Fayette tried, and he meant well – while meaning well is still far cray from doing the right thing, it is still something.

We however, have to talk about two further aspects, something that some contemporary books often like to gloss over, because it is not quite that pretty and simple.

There is this letter from Henry Laurens to La Fayette, dated October 23, 1777:

I have not seen the french Gentleman who did me the honour to bring your Letter, but will enquire of your black Servant where he may be found & you may depend upon me Sir to attempt, at least, to Serve him, nor shall the Subject concerning Mr. De Valfort depart from my mind.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 1, December 7, 1776–March 30, 1778, Cornell University Press, 1977, pp. 126-128.

The “black Servant” that Laurens refers to was an enslaved man that La Fayette’s aide-de-camp Edmund Brice purchased for 180 Pounds on August 4, 1777. We no neither the name of the men, his age, nor his fate. This is the only reference that we find in La Fayette’s papers and it is hard to say what happened to the man. From context is fair to say that he probably was not long with La Fayette.

Then there is another matter, proposed by La Fayette in a letter. Take the following summary with a grain of salt, since I have only read the letter once and that was in a rush. The letter was in relation to the Canada expedition – the expedition was chronically underfunded and there was supposedly private property that had been confiscated, among the property were a number of enslaved individuals. La Fayette proposed that in selling these individuals, enough money could be raised. The expedition was aborted in the end and La Fayette never again came up with such ideas, so I like to think that he learned his lesson there.

This turned into a rather long post, but I think that this topic needs an in-depth discussion, especially since La Fayette tends to be put on a pedestal in some representations. As I already said, he meant well and had the best of intentions, even more so as he grew older, and he was determined to do something instead of twiddling his thumbs and his influence certainly helped the cause. He saw slavery as an evil that needed to be abolished. But we also have to see the wider picture and realize that he was an imperfect man with a fair amount of flaws.

#ask me anything#anon#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#adrienne de lafayette#adrienne de noailles#edmund brice#george washington#henry laurens#john adams#american revolution#american history#french history#french revolution#history#black history#slavery#1777#1786#1825#1788#1783#1785#james armistead lafayette#historical documents#founder online#jules germain cloquet#charles sumner#thomas clarckson#letter

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

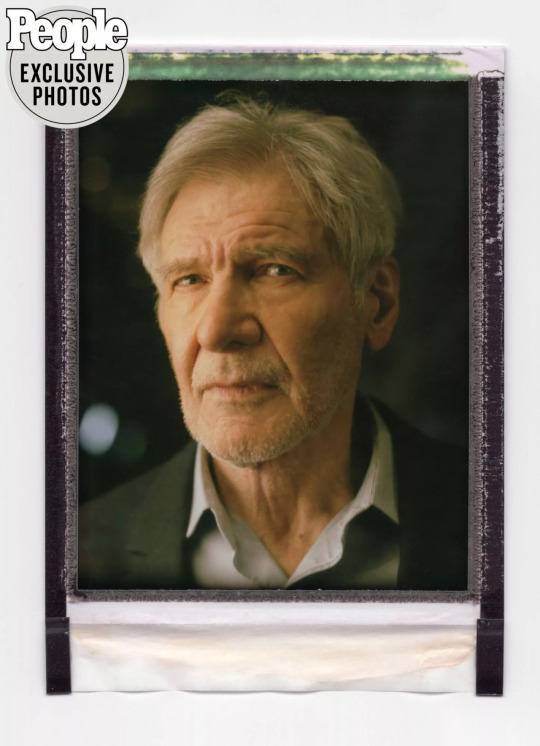

Harrison Ford: 2022 review

2022 has been a very busy year for Harrison! From finishing the next instalment of the Indiana Jones franchise, to star in his first TV shows in decades: the sitcom Shrinking and the western 1923. Let's have a look at the summary of this glorious year for Harrison's career.

JANUARY: no news. but Harrison is probably still working on the set of Indiana Jones 5.

FEBRUARY:

Frank Marshall announces Indiana Jones 5 had wrapped principal photography.

Harrison visits Barcelona

MARCH:

Harrison invites the whole cast and crew of Indy 5 to a wrap party in London

APRIL:

Harrison Ford To Star In ‘Shrinking’ Apple TV+ Series

Indiana Jones 5 Has Same Feel As The Original, Says Mads Mikkelsen

Cryptic picture of Harrison celebrating Easter:

Disney Exec Teases Guardians of the Galaxy 3, Indiana Jones, The Marvels, and More Footage Coming Soon

MAY:

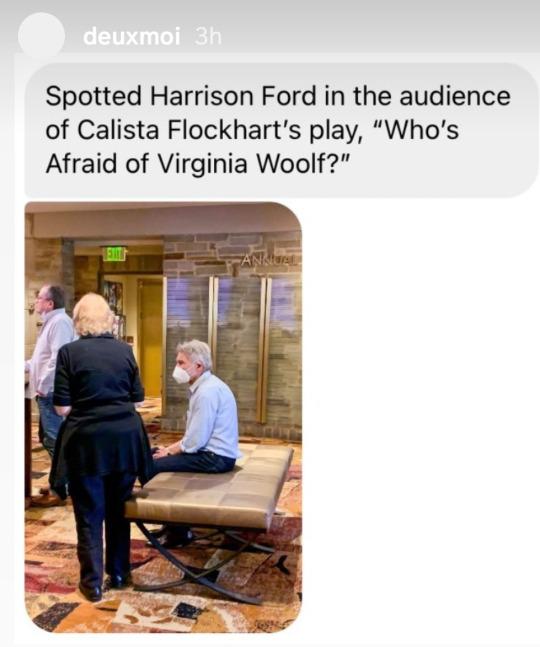

Harrison For attends the play "Who's afraid of Virginia Woolf?", played by his wife Calista Flockhart

New promo picture of Indy 5:

Harrison spotted in Fort Worth, Texas

instagram

Harrison Ford and Helen Mirren to Star in ‘Yellowstone’ Prequel ‘1932’

Helen Mirren and Harrison Ford are joining the “Yellowstone” universe in the upcoming series “1932” for Paramount+.

“1932,” which is the show’s working title, is an origin story introducing a new generation of the Dutton family. It’s set to explore the early 20th century when pandemics, historic drought, the end of Prohibition and the Great Depression all plague the mountain West and the Duttons who call it home,” the streamer said in a release.

(Note that the actual title of the show is 1923)

‘Indiana Jones 5’ First Look: Harrison Ford Returns as Swaggering Adventurer

Star Wars Celebration: Harrison Ford Makes Surprise Appearance for John Williams Birthday Tribute, Gives ‘Indiana Jones 5’ Update

JUNE:

Brett Goldstein Takes His ‘Ted Lasso’ Skills To ‘Shrinking’ Comedy With Harrison Ford At Apple TV+

JULY:

Directing this fellow this week. One of the highlights of my career.

(I’m not sure but this could be on the set of Shrinking, the new show for Apple TV)

Surprise party on the set if Shrinking to celebrate Harry's birthday

instagram

AUGUST:

Warner Bros. Wanted Harrison Ford to Play Kevin Smith's Perry White

Kevin Smith reveals Warner Bros. wanted Harrison Ford to play Perry White in his episode of Strange Adventures, the cancelled HBO Max anthology show.

SEPTEMBER:

Exclusive: Harrison Ford In Talks For Fantastic Four Role

According to our trusted and proven sources, Marvel Studios wants Harrison Ford for the upcoming, mysterious Fantastic Four movie.

(I must say this hasn't been confirmed yet)

Harrison on the set of 1923:

instagram

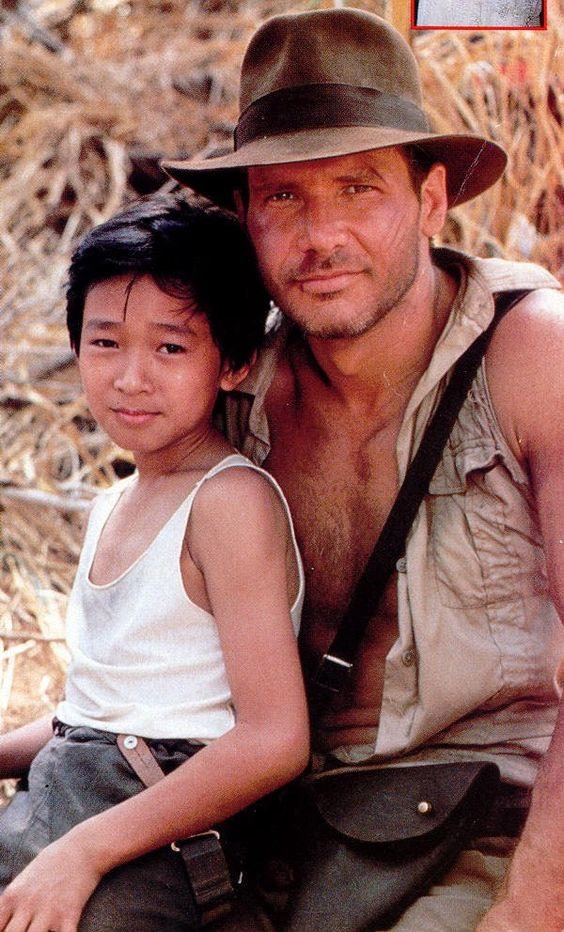

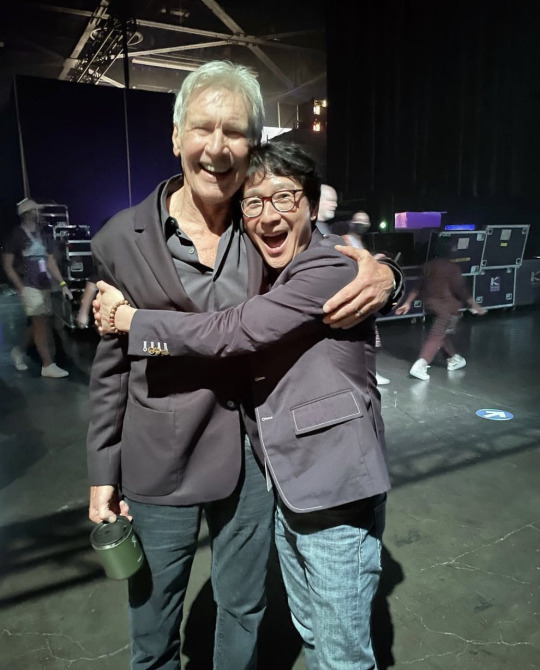

Harrison Ford and Ke Huy Quan reunite 38 years after ‘Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom’.

The trailer of Indiana Jones 5 is released to the Press, together with an exhibition of the costumes used in the movie

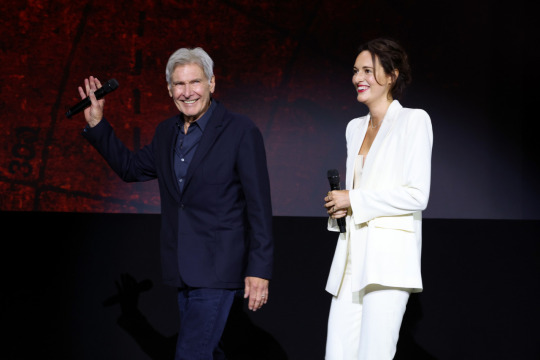

James Mangold and Harrison Ford debuted the first footage from the film at D23 Expo.

Harrison Ford, Phoebe Waller-Bridge and director James Mangold surprised fans at D23Expo.

OCTOBER:

Harrison Ford Set As General Thaddeus “Thunderbolt” Ross For ‘Captain America: New World Order’, Will Star Opposite Anthony Mackie

It’s official. Harrison Ford (Indiana Jones franchise) will be taking over the Marvel role of General Thaddeus “Thunderbolt” Ross, beginning with Phase 5 title Captain America: New World Order. He’ll star opposite Anthony Mackie, with Shira Haas, Tim Blake Nelson and Carl Lumbly also among the ensemble.

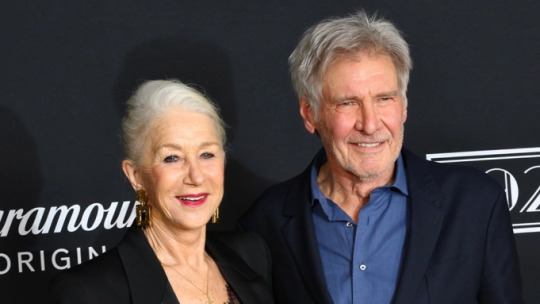

1923: Harrison Ford & Helen Mirren Series Expanded to Two Seasons, Paramount+ Sets Premiere Date

1923 is coming soon to Paramount+, and the series will stick around a bit longer than expected. What was expected to be a one-season limited series, has now been expanded to two eight-episode seasons. The Yellowstone prequel series will star Harrison Ford, Helen Mirren, Sebastian Roché, Darren Mann, Michelle Randolph, James Badge Dale, Marley Shelton, Brian Geraghty, Aminah Nieves, Julia Schlaepfer, Brandon Sklenar, Robert Patrick, and Jerome Flynn.

The series will arrive on Paramount+ on December 19th with a special two-hour premiere.

NOVEMBER:

1923 First Look: Harrison Ford and Helen Mirren Come to Yellowstone

The pair unveil their new series set at the Dutton ranch a century ago. “These are extraordinary people in an extraordinary time,” Ford says.

'1923' Teaser Offers First Exciting Look at Harrison Ford and Helen Mirren in 'Yellowstone' Spinoff

youtube

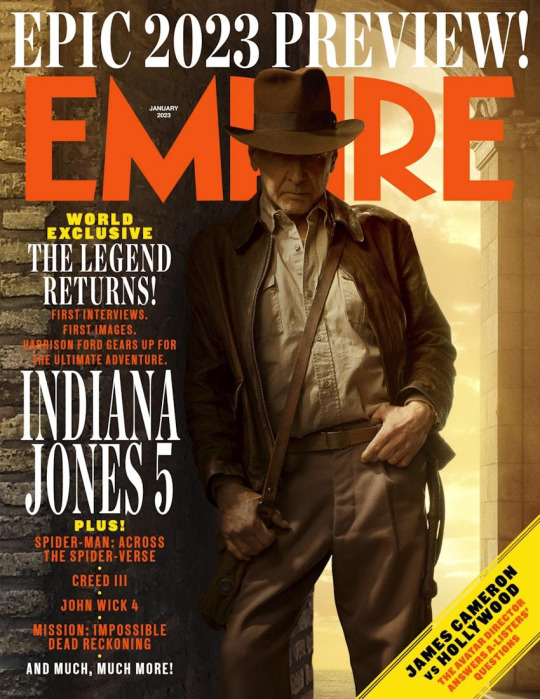

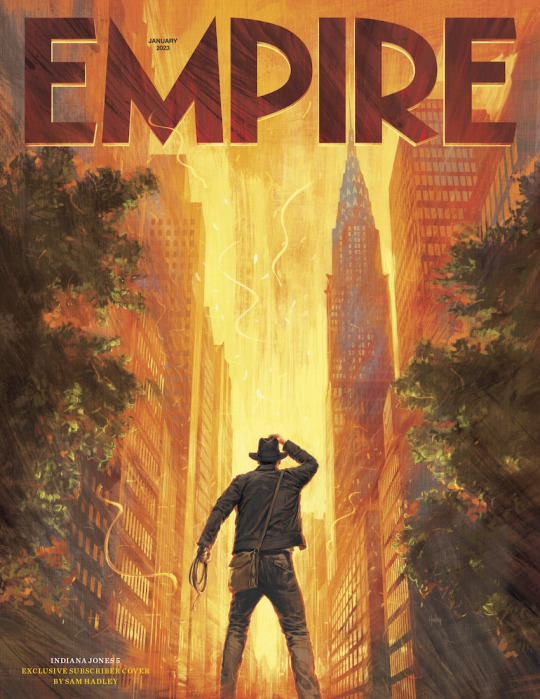

Empire’s World-Exclusive Indiana Jones 5 Covers Revealed

1923 Official Trailer:

youtube

'Shrinking' teaser trailer released

DECEMBER:

Indiana Jones 5 Official Trailer and Title released: Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny

youtube

See Helen Mirren and Harrison Ford in '1923' Premiere Photos — Taken with a Camera from the 1920s!

Helen Mirren Praises Her ‘1923’ Co-Star Harrison Ford at Premiere: ‘He Taught Me a Great Deal About Film Acting’

“1923” LA Premiere Screening & After Party

Harrison Ford Loves His Craft. ‘1923’ Tested His Limits.

#harrison ford#noticias de harrison ford#noticias 2022#hellen mirren#1923#taylor sheridan#Brandon Sklenar#Julia Schlaepfer#jerome flynn#darren mann#isabel may#brian geraghty#sebastian roche#indiana jones#indiana jones and the dial of destiny#indiana jones 5#james mangold#steven spielberg#john williams#frank marshall#kathleen kennedy#phoebe waller bridge#antonio banderas#john rhys davies#shaunette renee wilson#thomas kretschmann#toby jones#boyd holbrook#mads mikkelsen#lucasfilm

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Brian Handwerk, 11 May 2023

Mother’s Day is one of the year’s biggest greeting card occasions, but it definitely didn’t start out as a Hallmark holiday.

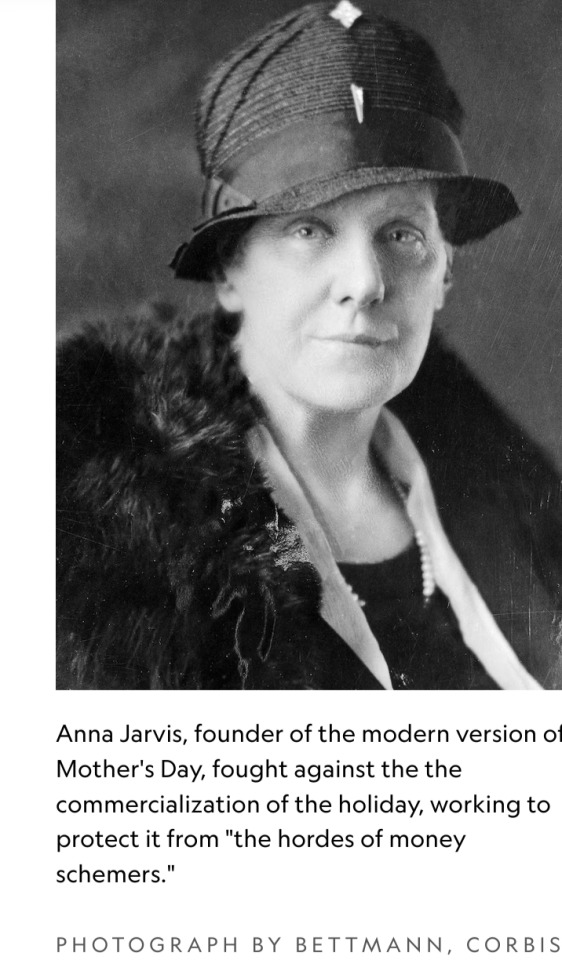

The Mother’s Day we celebrate on the second Sunday in May exists largely due to the incessant efforts — some might say maniacal single-mindedness — of a woman named Anna Jarvis.

But Jarvis wasn’t the first American to promote the idea.

Early attempts to get the holiday going focused on bigger social issues, such as promoting peace and improving schools.

But the version of the day that finally did catch on became its founder’s worst nightmare.

Early Mother’s Day celebrations

Mother’s Day was initially launched by antiwar activists in 1872.

Julia Ward Howe, better remembered for writing "The Battle Hymn of the Republic," advocated a Mothers’ Peace Day on which pacifist women would gather in churches, social halls, and homes to listen to sermons or essays, sing, and pray for peace.

American cities like Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago held annual Mother’s Day services, centered on pacifism, every June 2 until about 1913.

But these faded away, as did the mothers’ pleas for peace when the world entered World War I.

Another early Mother's Day effort was led by teacher and principal Mary Towles Sasseen, of Henderson, Kentucky.

Her idea, launched in 1887, focused on schools:

Sasseen wrote a guide, Mother’s Day Celebrations, with the hope that school systems around the country would observe Mother’s Day receptions to strengthen ties between students, parents, and teachers.

But by the time she died in 1924, Sasseen’s Mother’s Day never made it far beyond Kentucky.

Who really founded Mother’s Day?

In February 1904, Frank Hering, a University of Notre Dame faculty member, football coach, and national president of the Fraternal Order of Eagles delivered a speech entitled “Our Mothers and Their Importance in Our Lives.”

It was the first public call to set aside a national day to honor mothers.

Although that organization still bills Hering and itself as the “true founders of Mother's Day,” his role in proposing the holiday was soon eclipsed by the tireless efforts of Jarvis to publicize and promote the holiday — and herself as the founder.

Jarvis’s labors, which made Mother’s Day a reality, began with a wish to honor her own mother — who had attended Julia Ward Howe’s gatherings and prayed, quite literally, for such a day to exist.

In 1908, when Jarvis organized the first official Mother’s Day celebrations in Grafton, West Virginia, and Philadelphia, she chose the second Sunday in May because it honored the anniversary of her mother’s death.

As Jarvis’s campaigning rapidly expanded Mother’s Day observations across the country, she rejected the idea that Hering’s earlier suggestion had anything to do with it.

An undated 1920s statement entitled “Kidnapping Mother’s Day: Will You Be an Accomplice?” explained her attitude towards Hering:

“Do me the justice of refraining from furthering the selfish interests of this claimant, who is making a desperate effort to snatch from me the rightful title of originator and founder of Mother’s Day, established by me after decades of untold labor, time and expense.”

Jarvis, who never had children, acted partly out of ego, says Katharine Antolini, an historian at West Virginia Wesleyan College and author of Memorializing Motherhood: Anna Jarvis and the Struggle for Control of Mother's Day.

“Everything she signed was Anna Jarvis, Founder of Mother's Day. It was who she was."

How Mother’s Day became a national holiday

Jarvis had a point; she’s clearly the primary person responsible for launching the holiday as a national celebration.

Founding Mother’s Day and aggressively protecting her ownership of the holiday became her life’s work.

In her mission to win the holiday national recognition, Jarvis petitioned the press, politicians, churches, organizations, and individuals of influence including, notably, the wealthy Philadelphia department store magnate John Wanamaker.

Wanamaker embraced Jarvis’s idea and promoted a 10 May 1908 gathering at his department store, which Jarvis herself addressed.

The Philadelphia event drew a reported 15,000 people and each one received a free carnation — at least while they lasted. Mother’s Day was off and running.

Under relentless lobbying from Jarvis, state after state began to observe Mother’s Day.

In 1914, President Woodrow Wilson finally signed a bill designating the second Sunday in May as a legal holiday, Mother’s Day.

It was dedicated “to the best mother in the world, your mother.” The idea of honoring mothers was appealing.

General John “Black Jack” Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, highlighted the value of the holiday in a general order he issued on 8 May 1918 asking officers and soldiers to write letters home on Mother’s Day.

He wrote: “This is a little thing for each one to do, but these letters will carry back our courage and affection to the patriotic women whose love and prayers inspire us and cheer us on to victory."

In 1934, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt got into the act.

The avid stamp collector sketched a design for a Commemorative Mother’s Day Stamp based on the famous “Whistler’s Mother” portrait.

Unfortunately for FDR, Anna Jarvis didn’t approve.

She found the design ugly and made clear her intention that the words “Mother’s Day” not adorn the stamp — they never did.

Mother’s Day and commercialization

Business owners like John Wanamaker and Philadelphia's florists likely saw Mother’s Day’s commercial potential from that very first Sunday in 1908.

But Jarvis had many strong opinions about how the holiday should and should not be celebrated.

Foremost among them was her hatred of profiteering, even by charitable institutions.

Just a few years after that first Philadelphia Mother’s Day, one story goes, Jarvis ordered a “Mother’s Day Salad” at Wanamaker’s Tea Room — and dumped it on the floor.

Jarvis meant the holiday to be one of quiet reflection and personal relations between mothers and children.

“To have Mother’s Day the burdensome, wasteful, expensive gift day that Christmas and other special days have become is not our pleasure," she wrote in the 1920s.

“If the American people are not willing to protect Mother’s Day from the hordes of money schemers that would overwhelm it with their schemes, then we shall cease having a Mother’s Day—and we know how.”

If Jarvis really did have some plan to stop people from profiting off of Mother’s Day, that plan amounted to exactly nothing.

In 1948, Jarvis died in a Pennsylvania sanitarium, aged 84, penniless after spending her fortune fighting to maintain control over Mother’s Day.

Today, Mother’s Day isn’t just commercialized, it’s a retail juggernaut.

In fact, only Back-to-School and winter holidays inspire Americans to spend more money per person than Mother’s Day, according to the National Retail Federation.

The haul is over 30 billion dollars in all.

Hallmark profits handsomely from that spending; it’s the third biggest card-giving day of the year.

And, to the delight of florists, about three out of four people faithfully send mom flowers.

More than half of all celebrators also plan special outings for their mothers, gifting tickets to concerts and sporting events—or a day at the spa.

And Mother’s Day is also the busiest day of the year for restaurants, according to annual research surveys from the National Restaurant Association.

More than one in four people go out for a meal with mom each year, and many more at least order takeout so that no one has to spend the special day in the kitchen.

If the holiday has become a runaway moneymaker, Jarvis would have loathed, at least gathering around a table for those Mother’s Day meals offers children a chance to personally honor their moms in the way she always intended.

#Mother's Day#Anna Jarvis#Julia Ward Howe#Mary Towles Sasseen#Frank Hering#President Woodrow Wilson#President Franklin Delano Roosevelt#Hallmark

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

What You Need To Know About The Origins Of Black History Month

Black History Month is Considered one of the Nation’s Oldest Organized History Celebrations, and has been Recognized by U.S. Presidents for Decades Through Proclamations and Celebrations. Here is Some Information about the History of Black History Month.

— By Jesse J. Holland | February 1, 2024 | Associated Press

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. locks arms with his aides as he leads a march of several thousands to the court house in Montgomery, Alabama, March 17, 1965. From left: Rev. Ralph Abernathy, James Foreman, King, Jesse Douglas, Sr., and John Lewis (partially out of frame). (AP Photo)

How Did Black History Month Start?

It was Carter G. Woodson, a founder of the Association for the Study of African American History, who first came up with the idea of the celebration that became Black History Month. Woodson, the son of recently freed Virginia slaves, who went on to earn a Ph.D in history from Harvard, originally came up with the idea of Negro History Week to encourage Black Americans to become more interested in their own history and heritage. Woodson worried that Black children were not being taught about their ancestors’ achievements in American schools in the early 1900s.

“If a race has no history, if it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated,” Woodson said.

Carter G. Woodson in an undated photograph. Woodson is a founder of the Association for the Study of African American History, who first came up with the idea of the celebration that became Black History Month. Woodson, the son of recently-freed Virginia slaves who went on to earn a Ph.D in history from Harvard, originally came up with the idea as Negro History Week to encourage black Americans to become more interested in their own history. (AP Photo)

Why is Black History Month in February?

Woodson chose February for Negro History Week because it had the birthdays of President Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. Lincoln was born on Feb. 12, and Douglass, a former slave who did not know his exact birthday, celebrated his on Feb. 14.

Daryl Michael Scott, a Howard University history professor and former ASAAH president, said Woodson chose that week because Black Americans were already celebrating Lincoln’s and Douglass’s birthdays. With the help of Black newspapers, he promoted that week as a time to focus on African-American history as part of the celebrations that were already ongoing.

The first Negro History Week was announced in February 1926.

“This was a community effort spearheaded by Woodson that built on tradition, and built on Black institutional life and structures to create a new celebration that was a week long, and it took off like a rocket,” Scott said.

Why The Change From a Week To a Month?

Negro History Week was wildly successful, but Woodson felt it needed more.

Woodson’s original idea for Negro History Week was for it to be a time for student showcases of the African-American history they learned the rest of the year, not as the only week Black history would be discussed, Scott said. Woodson later advocated starting a Negro History Year, saying that during a school year “a subject that receives attention one week out of 36 will not mean much to anyone.”

Individually several places, including West Virginia in the 1940s and Chicago in the 1960s, expanded the celebration into Negro History Month. The civil rights and Black Power movement advocated for an official shift from Black History Week to Black History Month, Scott said, and, in 1976, on the 50th anniversary of the beginning of Negro History Week, the Association for the Study of African American History made the shift to Black History Month.

Six Catholic nuns, including Sister Mary Antona Ebo, front row fourth from left, lead a march in Selma, Ala., on March 10, 1965, in support of Black voting rights and in protest of the violence of Bloody Sunday when white state troopers brutally dispersed peaceful Black demonstrators. (AP Photo, File)

Presidential Recognition

Every president since Gerald R. Ford through Joe Biden has issued a statement honoring the spirit of Black History Month.

Ford first honored Black History Week in 1975, calling the recognition “most appropriate,” as the country developed “a healthy awareness on the part of all of us of achievements that have too long been obscured and unsung.” The next year, in 1976, Ford issued the first Black History Month commemoration, saying with the celebration “we can seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of Black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history.”

President Jimmy Carter added in 1978 that the celebration “provides for all Americans a chance to rejoice and express pride in a heritage that adds so much to our way of life.” President Ronald Reagan said in 1981 that “understanding the history of Black Americans is a key to understanding the strength of our nation.”

— This Article by Former AP Reporter Jesse J. Holland was Originally Published on Feb. 2, 2017.

#Black History Month#Origins#Nation’s Oldest Organized History Celebrations#Dr. Martin Luther King#Montgomery | Alabama#Rev. Ralph Abernathy | James Foreman | Jesse Douglas Sr. | John Lewis#Negro History#Presidential Recognition

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Cincinnati Housewife’s Career As A Novelist Was Cut Short By Censorship

As near as I can tell, not a single copy of Jean Randolph Searle’s novels is to be found in any Tri-State library, unless you count the book stacks at Anderson University, 88 miles away in Indiana.

It is ironic that many of the libraries holding Miss Searles’ books today are conservative Christian schools like Anderson, affiliated with the Church of God, Roman Catholic Carlow University in Pittsburgh, and “non-denominational conservative Christian” Patrick Henry College in Purcellville, Virginia. The irony lies in the reception her books detonated in 1912 when they were condemned by the national and local branches of the Society for the Suppression of Vice as “too utterly indecent for our young to see.”

Jean Randolph Searles was a most unlikely pornographer. In fact, Jean Randolph Searles did not exist. That was merely the pen name of Adah Viola Benz of Price Hill, aka Mrs. George Benz, mother of two daughters and wife of an apparently quite successful real estate developer.

One might assume that Mrs. Benz, married to an established businessman, had the money to pay for the publication of her two 1912 novels herself – a practice known as vanity publishing. The books credit the “Press of Jennings & Graham,” a printer affiliated with Cincinnati’s Methodist Book Concern, a publishing house and bookstore located on West Fourth Street. The wording implies that Jennings & Graham published the books, but it is likely they only printed and bound them.

The books in question are “The Girl In The Slumber Boots” and its simultaneously published sequel, “Further Annals of the Girl In The Slumber Boots.” Although the books deal with marital infidelity and its consequences the (shall we say) “mechanics” of this infidelity are buried in baroque prose that relies ponderously on innuendo and not at all on forthright exposition.

In brief, Nell, the titular girl in the slumber boots (heavy knit slippers made to wear to bed) is unhappily married and walks in her sleep. One morning, she finds herself in the bed of an unhappily married doctor who leaves his apartment door unlocked. When Nell enters his darkened room in the wee hours, he thinks she is his wife and has his way with her. Somehow, this activity does not rouse the somnambulist and it is only when she awakens hours later that the full import of her transgression inspires her to action. Drama and trauma ensue, involving British gentry, ruined damsels, misadventures out West and the shenanigans of high society.

According to Alfred Segal at the Cincinnati Post [26 November 1929], the Society for the Suppression of Vice may not have even read the book. Their censorious ire may have been directed toward the illustration opposite the title page:

“It showed a woman in a nightgown confronting a man in a bathrobe. Her hand seemed to flutter towards her face in fear. He stared at her with the glum expression which men on old-fashioned posters frequently had. That was too much for the purity of the day. The book officially was ruled out of the stalls and sent back to the author.”

None of the Cincinnati newspapers reviewed “The Girl In The Slumber Boots.” One of the few published reviews, from the Monroe City, Missouri, Democrat [12 December 1912] is more than a little vague in its appraisal:

“It is too bad that anyone capable of writing as interesting a story as this one spoils it by taking the wrong view of what is right and what wrong. To be sure she straightens out matters in the second volume, Further Annals of the Girl In The Slumber Boots, but she doesn’t look at life right. The books are not wholesome – are not what we would want our young people to read.”

Well, that was in 1912. By 1929 – only 17 years later! – when the Post’s Segal interviewed the author, times had changed. Hemlines had skyrocketed from floor-length to knee-length. Women now smoked in public, for goodness’ sake. The new morality was reflected in the racy novels of the Roaring Twenties. As Segal explained:

“Words that would have been strange to the Slumber Boot Girl were sprinkled all over the pages. Details which she would have locked forever in her heart were shouted in black type. The erstwhile author thought perhaps her hour had struck. If she had written naughty things (with indecent pictures) too early in the century, she now could make up for it.”

Mrs. Benz, by now living on Shiloh Avenue in Clifton, took copies of her books downtown to Fourth Street, to Bertrand L. Smith, proprietor of the Traveler’s Book Shop, later to be known as Bertrand Smith’s Acres of Books.

“Smith glanced at the ‘indecent’ pictures and smiled sadly. He skipped through a few lines of the intimate passages and smiled still more sadly. ‘Madame,’ he said, ‘this ain’t nuthin’.’”

Smith accepted Mrs. Benz’s books and put them on sale. Buyers told Smith it was a relief to find decent books still for sale in Cincinnati. Still, Mrs. Benz would not allow Al Segal to print her real name for fear the taint of prior condemnation might still adhere to it.

George Benz died in 1937. A couple years later, Adah Benz revived her pen name and published another novel, “Only A Substitute Wife.” This time, the book was actually accepted by a legitimate publisher, Ruter Press, who also issued books of Caroline Williams’ artwork. Adah’s third novel appears not to have sold well and copies are hard to locate.

Adah Viola Rohrer was born in Elkhart, Indiana, in 1872 and married George Benz, a young and ambitious carpenter, in 1896. The young couple moved to Cincinnati in 1906, where George, in partnership with Sherman Weigold, built and sold a good number of houses in the northeast portion of Northside. Both George and Adah, aka Jean Randolph Searles, are buried in Goshen, near Elkhart, Indiana.

Adah’s books, while not preserved in Cincinnati, are on file in the Library of Congress and perhaps a dozen other libraries. They can be located online, where original editions fetch $70 or more.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

#fictober23 day eighteen

"This better be good"

original fiction

word count: 529

Rhiannon’s palms were sweating as she sat in her grad advisor’s office. She clutched the folder in her hands - full of photographic evidence, transcriptions of her tests with Josie, various conclusions she’d drawn from them.