#abolitionist fashion

Text

CARE For People, Defund Police. Screen-printed by formerly incarcerated people and our loved ones.

#defundthepolice#abolish prisons#abolish ice#abolition is creative#abolitionist fashion#abolition#police abolition#prison abolition#formerly incarcerated

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

On July 5, 1852, Frederick Douglass gave a speech at an event commemorating the signing of the Declaration of Independence, held at Rochester's Corinthian Hall. It was biting oratory, in which the speaker told his audience, "This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn." And he asked them, "Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak to-day? …

“What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer; a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sound of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciation of tyrants brass fronted impudence; your shout of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanks-givings, with all your religious parade and solemnity, are to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy -- a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices more shocking and bloody than are the people of the United States, at this very hour."

This speech was delivered 76 years after America's Independence Day, and 13 years before slavery ended.

I bullshit you not.

#frederick douglass#abolition of slavery#abolitionist#american slavery#badass#badassery#bad motherfucker#cool stuff#random#1800s aesthetic#1800s fashion#1800s

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not only were there real, existing feminists who hated corsets and marriage in the 19th century, but especially if you’re talking about Louisa May Alcott and the kind of New England progressive ideas she held and that her characters hold, these were inextricable from abolitionism! The kind of New England abolitionist women that the Marches are a fictional version of were openly scornful of a lot of popular fashions and kinds of parties because they hated slave-grown cotton and the decadence of Slave Power.

667 notes

·

View notes

Note

Madame Marzi I must defer to ur wisdom

Recently you rb’d a painting with some younger ladies and in the tags talked a bit about short hair in Victorian Times

Do you have any reference for how shorter hair was styled at the time? I’ve seen plenty of paintings and such with VERY short hair (post illness or perhaps childbirth) where all you can really do is smooth it back, but what about that awkward, past the shoulders sort of stage where it’s too long to just brush back but too short to do much to? Surely they had some styling guides..?

(Also, a side question— how old would one be before going from shorter skirts to adult/full length ones?)

The two little girls in the garden (probably preteens-young teens)? Yes, I did!

It's hard to find images of women with in-between hair lengths, and I'm not sure why. Possibly because they'd find ways to put it up with false hair, whereas hair too short to put up is more obvious in photos. This could also have to do with the type of woman who has pixie- or bob-length hair voluntarily vs. mid-length: the latter is more likely to be attempting a grow-out, and thus to try her darndest to do The Culturally Accepted Long Hair StylesTM where a lady who chose a much shorter look wouldn't care. If that makes sense? Because, indeed, some of the women with very short hair were not ill or postpartum: ladies could, and did, choose to eschew long locks back then. It wasn't very common, but it happened.

(Nicole Rudolph has an excellent video about localized short hair trends for ladies during the Victorian era.)

You see a lot of these bob-type looks in photographs where the hair is center-parted and either naturally curly or curled on purpose, around the mid-19th century:

(1850s or 60s)

(Author, feminist, and abolitionist Anna Elizabeth Dickinson- no relation to Emily that I know of, though Anna was also a queer female writer around the same era -c. 1860s. She wore her hair short all her life, so it was voluntary in this case.)

(Also 1860s.)

Pre-Raphaelite muse Fanny Eaton frequently appears to have chin-to-shoulder length hair, though given that she was Black with a corresponding hair texture, it's hard to tell what the actual length is- it may be long and looped up in the 1850s-60s styles popular when she was most commonly painted (most free Black women in England and the US wore styles also popular with white women, to the best of their abilities given that fashion plates assumed European-textured hair as the "norm"):

(Fanny Eaton, 1861. Also worth noting that we have no images of what her hair looked like when she wasn't posing for fantastical paintings.)

I've never actually seen an image of a Victorian woman with mid-length hair outside the context of theatrical or artistic images from the end of the century, now I think of it. Huh. It's a mystery, I suppose!

As for skirts, while in earlier periods children had basically worn miniature adult clothing, it became fashionable around the 1830s-40s to dress girls in short skirts and boys in short pants. The usual rule was knee-length until around age 10, then mid-calf-length until somewhere between 16 and 18 when skirts would be "let down" and the girl would start wearing her hair up, becoming a young adult in the eyes of society. (Contrary to popular belief, this had nothing to do with marriage- while you were theoretically eligible for it when you started dressing as an adult, girls/women younger than 20 were still often considered a bit too immature to marry. It wasn't forbidden, but many people thought it unwise. And yes, unmarried young women did still wear their hair up and their skirts long.)

...unless she preferred her hair short, which as you can see, was an option!

86 notes

·

View notes

Note

genuine question: how do you reconcile police abolition with marxism-leninism? isn't having police a notable feature of marxist leninist regimes? this isn't a gotcha I'm just curious about how you reconcile this or what flaws exist in my conception of marxism-leninism

so there's an obvious theoretical answer to this, a more in-depth theoretical answer to this, and a practical answer that derives from the latter. the obvious theoretical answer is that my police abolitionist stance is based on the role of the bourgeois police force as enforcers of private property law--as the front line of class warfare against the working class. there is a material difference in the incentives and structures of a socialist police force operating on behalf of the working class as an organ of class warfare against the bourgeoisie.

but this isn't a complete and satisfying answer. i mean, obviously. the idea that the soviet militsiya and nkvd were in any way worse than the tsarist police and secret poice that came before them--or, for that matter, meaningfully worse than contemporary capitalist police forces, or the capitalist police forces in the post-soviet bourgeois states--is an anticommunist fabrication. but the idea that the militsiya was without its problems, that ordinary citizens did not have to worry about effectively unaccountable brutality in their interactions with these bodies, is also pretty detached from material reality. i think we can safely establish that the existence of a proletarian state alone isn't enough to solve the problems of a police force.

so what's the more complex theoretical approach? well, in a little number called state & revolution, v.i. lenin talks about 'special bodies of armed men' as opposed to 'self-acting armed organisations'--essentially drawing the conclusion that the former (police & military) were essentially removed from accountability--by virtue of their unique position and special privileges afforded to them by their uniforms, they're able to act as if and consider themselves as external to society, and so they're invariably doomed to be detached from the working class even if they are operating in their ostensible interest. meanwhile, the 'self-acting armed organization' is more like a militia, in the traditional sense of being fundamentally made up of ordinary people. this was why the militsiya was named that, because although it did ultimately develop into a 'special body of armed men' it began life as a revolutionary milita.

& i want to be clear that the importance of the self-acting armed organization is not an embrace of 'community justice' or whatever thinly veiled mob justice in a nice hat that anarchists like to sing the praises of. these militias should still be organized and structured, so that they can be accountable. but the importance of them being self-acting organizations instead of special bodies of armed men is that they are not removed from society. lenin discussed at length the example of the paris commune, and how civil servants within the commune were paid exactly the same as anyone else--and discussed how the advancement of both technology and education could create a world in which any citizen could (and therefore, indeed, would) take up a role in the administration of their society.

i think it therefore follows from what lenin wrote that the theoretical model of policing as self-acting armed organizations should result in a socialist state in which nobody is professionally, as a career, a 'police officer'. the work that constitutes 'policing' in a post-revolutionary society should be simple enough that anybody can and does do it--not on pure self-initiative but in a mobilized and organized fashion. this prevents the elevation of police to a body 'above society' and therefore capable of and even inclined to performi mass violence against that society.

and of course, the eternal question for marxists, what does this look like in practice: i think there have been succesful and interesting experiments in this sort of thing in socialist projects across the globe. most notably, i think that the cuban committees for the defense of the revolution are a good place to start, & so are mao's eight points of attention and three rules of discipline & the processes (not always succesful) to create accountability to the masses among the red guards and red army during and after the chinese civil war.

& of course, once there are no more classes, there will be no need for a state, or an apparatus to suppress the bourgeoisie more generally, and so the police will wither away with the rest of it.

224 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've noticed that calling yourself a prison abolitionist is very fashionable online but being one isn't.

99 notes

·

View notes

Photo

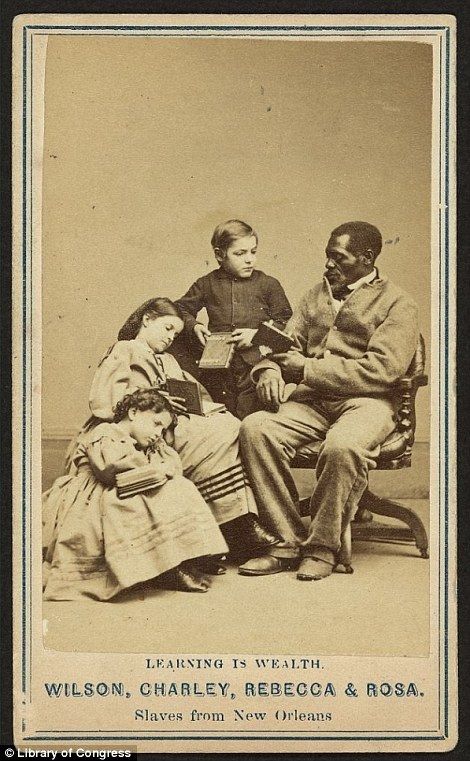

Cécile’s Parlor Outfit and Marie-Grace’s Skirt Set take the place typically occupied by a girl’s school set. They correspond with the book Marie-Grace and the Orphans, in which a light-skinned, possibly Black baby is left on Marie-Grace’s father’s doorstep, which soon brings them face-to-face with slave-catchers. I’m glad that at least in 2011 AG was still tacking difficult historical subjects. White-looking children being held in slavery became an abolitionist cause celebre during the Civil War, so it’s cool to see that subject being brought up.

The oldest Catholic school in the US, The Ursuline Academy, began teaching girls in 1727, and it was open both Black and White students. New Orleans opened its first official public schools in 1841, but I haven’t been able to find out if they were segregated or not. All that aside, it means Cécile and Marie-Grace probably would have gone to school, even though home instruction was still popular.

Their collection does come with an education-y desk, though! I absolutely love the transforming table desk!

a real-life example:

(found by @in-pleasant-company)

Cécile’s parrot, Cochon, is super cute, and parrots were actually a very popular pet at the time. They were brought into port cities from far away and were exotic, colorful, and clever in a way that made people go nuts for them.

As far as fashion goes, I’m not a huge fan of Cécile’s little jacket. Even tough it’s not 100% inaccurate, it likely would have matched the skirt she’s wearing.

Marie-Grace’s dress, on the other hand, is great!

(The Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

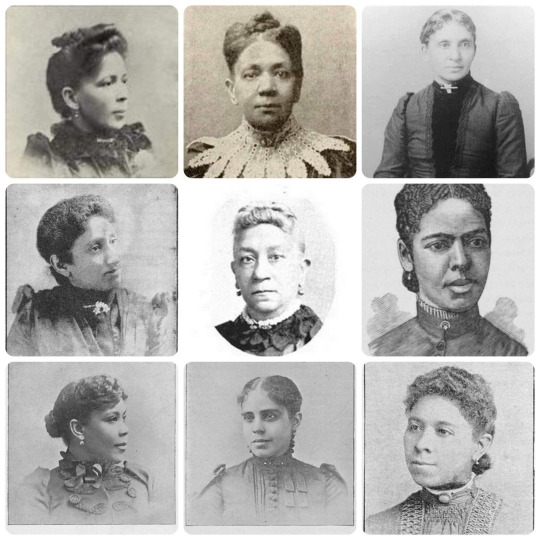

Nine trailblazing women from Monroe A. Major’s 1883 book, “Noted Negro Women Their Triumphs, and Activities.” These women believed in education and became teachers, journalists, and leaders. First row: Della Irving Hayden (1851-1924), was born a slave, graduated from what is now known as HamptonUniversity in 1877. Founded Franklin Normal and Industrial Institute in Virginia in 1904; Fannie Jackson Coppin (1837-1913), born a slave, determined to get an education at Rhode Island State Normal, went to OberlinCollege. Taught Latin, Greek, & math at the Institute for Colored Youth in Philadelphia; Charlotte Forten Grimke (1837-1914), grew up in a prominent abolitionist free black family. Grimke went south to educate boys and girls in South Carolina; Second row: Julia Ringwood Coston, a journalist from Cleveland, Ohio, and editor of Ringwood’s Afro-American Journal of Fashion; Sarah Jane Woodson Early (1825-1907), was born to free parents in Chillicothe, Ohio, enrolled at Oberlin college and graduated in 1856 with a bachelor’s degree to teach English and Latin, taught at WilberforceUniversity; Lucy Wilmot Smith (1861-1889), a writer, educator, historian, editor, suffragist, and journalist. In 1884 became a journalist for the American Baptist, later became its editor; Third row: Rosa D. Bowser (1859-1941), first black teacher hired in Richmond, Virginia, she was a correspondent for The Women’s Era; Mary V. Cook Parish (1862-1945), professor at Kentucky Baptist College, journalist for The American Baptist, editor of Our Women and Children; Frankie E. Harris Wasson (1850-1933), her parents were involved in the UndergroundRailroad, graduated from Oberlin College in 1870, taught for 54 years, was a principal, published a book of poetry in 1886.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

about me:

♡21, virgo sun.

♡chilean communist

♡soon a history teacher

♡ new to radfeminism and being GC, formally nonbinary and TRA.

♡non political interests: shoujo manga, art, women and fashion history, history as a whole lol, cats, tea, pottery, reading, pink colored stuff.

♡ political interests/stances: anti porn/prostitution, pro sex workers, anti abrahamic religions, pro women, gender abolitionist, anti capitalist, anti nuclear family, pro mothers.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

a new world is growing. As our roots pierce the concrete - our imaginations blossom new realities the violence-based world can see.

Abolition is Creative Hoodie by For Everyone Collective - fashion free from harm.

#prison abolition#abolitionist fashion#created by formerly incarcerated people#streetwear#ethical fashion#slow fashion#living wages#abolition is creative#police abolition#healthcare for all#housing for all#a new world is growing#for everyone

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Negro Family: The Case for National Action (from here on referred to as The Report), known in popular vernacular as The Moynihan Report (1965), celebrated its fiftieth anniversary in 2015. In 1965, amidst a backdrop of Black urban rebellion, Moynihan’s anxiety about the crumbling fabric of the negro family headed by the Black matriarch inspired his characterization of the black family as a “tangle of pathology.” Alongside the sociologist’s attempts to police and surveil unruly Black urban life through producing the ‘Black family’ as an object of knowledge and problem for national security, Moynihan also reaffirmed the family as the singular epistemic mode of knowing and regulating the self and American (or US) civil society. Moynihan affirmed for the United States that, “The family is the basic social unit of American life.”

Since The Report’s publication, Black scholars and activists have felt compelled to respond to The Report and its legacy that has marked Black single mothers, Black genders, sexualities and family formations as self (and nationally) destructive. Since its introduction into mainstream public discourse in 1965 the Black Matriarch has embedded itself in the US imaginary in an almost archetypal fashion. In fact it has become the primary discourse used to both imagine and speak about the ‘Black family’ specifically as a problem and thus an object of disquiet. Black academic ‘feminists’ and Black women activists have critiqued both Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s and Black bourgeois attempts to castigate Black female headed households as perverse and deviant. Black feminists have labored to illumine the ways that the “controlling image” of the Black matriarch forecloses upon the possibility of imagining viable non-nuclear family formations, vilifies Black single female sexual autonomy, reinforces an ethos of personal responsibility and disavows structural inequality making it almost impossible to imagine a politics of redistribution. To date, Black feminist and queer scholarship continues to propose Black matriarchal, non-heteropatriarchal and queer models of affirming Black family life in an attempt to counter the legacy of pathologization left by The Report.

However, after fifty years of ever-evolving and increasingly nuanced Black feminist responses to The Report, rarely do critiques and alternative modes of the Black filial interrogate the viability of the notion of the family itself. While, Black feminist responses to The Report and the discourse of Black matriarchy have argued for alternative forms of family, ranging from intergenerational, extended, non-sanguial, and queer; the family as a sociological unit and as a self evident and natural form of human organization persists. Even when Black and Black queer feminists call for alternatives to the the ‘normal family,’ these modifications and revisions to the family still retain attachments to the liberal humanistic concept of the filial as the organizing frame for legible Black collective life.

Black ‘feminist’ abolitionist responses that trouble the very concept of the family as a way of organizing Black life still remain unexamined and perhaps even “unthought.” In this essay, I argue that while most Black feminist and queer modes of critique exhibit a suspicion or ambivalence toward the family, the responses of Kay Lindsey (1970) and Hortense Spillers (1987) offer a distinctly abolitionist critique of the family. Unlike “suspicious” or reformist critiques, which tend to hold onto at least some aspects of the normative and liberal family model, the abolitionist frame organizing this essay opens up the possibility of naming and doing Black relations outside of the categories that currently name humanness. This essay focuses on Black abolitionist critiques that denaturalize the family as a normative and humanizing institution to which people should aspire to belong. More importantly, it opens up conversations about alternative modes of naming the self in relation to others outside of the Western humanist tradition.

Because of the ongoing disruption of Black sociality and the understanding that Black relations are under assault, the ‘Black family’ has taken on an almost sacred significance within Black social life due to its heralded role as a protective mechanism to Black vulnerability and violation. The Black praxis of family as an everyday lived experience has the potential to ground people, provide material and emotional support and affirm the spirit of many Black people who feel vulnerable in the world. For many, including myself, family helps make life livable amidst everyday enactments of antiblack violence. To be clear, this essay does not indulge in a nihilistic destruction of the family for the sake of Afro-pessimistic intellectual experimentation. Rather, it is precisely because of this need for and commitment to Black sociality as a dynamic and inventive practice that this essay presses toward otherwise modes of thinking and being with one another. This essay conscientiously attends to the ways that the western notion of the family functions as a site of violence and dehumanization that threatens to engulf Black sociality. While Black feminist, queer scholarship and creative work have called for a reimagining of the Black family on radically different terms (non patriarchal, egalitarian and queer) they often do not critique the family in ways that draw attention to the violent ways that the family emerges as a category of violent forms of humanism. I consider the possible abolition of the family (and Black family) because I fear that the institution crowds out the dynamic and emerging ways that Black people reimagine and invent new modes of relation.

Tiffany Lethabo King from “Black 'Feminisms' and Pessimism: Abolishing Moynihan's Negro Family”

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

sorta. learning how to separate my gender from how other people perceive and treat me. that and separating my gender identity from gender performance and the idea that i have to DO anything or have any specific trait to be a woman

i dunno. if gender describes your relationship to society and your relationship to your body and sex characteristics, then there is an expectation to perform specific roles based on your relationship to your body, which is pretty wierd and we could probably do without that. so, i guess in that sense, im a gender abolitionist

i don’t consider myself a woman because i was assigned female at birth, i consider myself a woman because it describes my relationship to my body. i don’t consider my (de)transition a return because i don’t remember what it was like to live as someone who was perceived as a girl and i’ve never been perceived as a woman, just a feminine trans person (and only online, offline i’m treated as an autistic cis man) so i’m having to figure out what my womanhood means to me for the first time instead of having it just given to me or something i had at some nebulous ~before~

but it’s. i don’t think being a woman means you have to be feminine in any meaning of the word. i don’t think i have to be seen as a woman to be one. i don’t even think i have to dislike masculine terms being used for me. i also don’t think that not conforming to the expected presentations of my gender makes me nonbinary. (nb people are chill i am just tired of being degendered in trans* spaces and having people making a big deal over my gender/pronouns because i don’t “look like” my gender)

i’m just a woman with a deep voice and body hair and broad shoulders and facial hair and an adam’s apple and a strong brow. i’m just a woman that wears clothing made for men and who wears binders instead of bras most of the time. i’m just a woman who wears makeup only once or twice a year and who doesn’t do anything centered around anti-aging. none of that makes me less of a woman, it just makes me less feminine which is fine

femininity is nice but a lot of it is either based on making women more consumable to men or just isn’t ideal for a construction worker. like. i love lolita fashion but it is not remotely osha approved. i can barely get away with tying my jacket around my waist lmafo

and i mean. i like men. 90% of my coworkers are men and i generally fuck with them. i’m also promised to a man who is my priority in life.

but at the same time, i’m not going to go out of my way to be appealing to men or even think about it in my day to day life because i’m a person who enjoys men, not a perfume ad. yeah i dress up for dates and enjoy when my promised finds me attractive but being desirable isn’t the same as being consumable. when i perform femininity for my promised, he enjoys the show but sees me as an actor instead of a character if that makes sense?

i dunno. i love being feminine in over the top ways that make me feel powerful and confident but it’s… a lot to do outside of the context of conventions (shout out to conventions for giving me a way to explore new presentations in public without being afraid of getting hate crimed fr)

i guess for me it feels wierd to be a woman almost exclusively attracted to men because so much of how people talk about wlm is centered around the man’s attraction to the woman or the woman making herself attractive to the man when i center myself in my attraction to men. i generally don’t think about making myself attractive to a man i’m not actively going on a date with, i think about what i want to do to him and what he could do for me. yeah it’s a little selfish but nobody’s complained yet B;)

tl;dr: i’m still a woman when i fulfill male stereotypes. femininity as a way to feel powerful, pretty, and/or desirable is nice. femininity as a set of rules pushed on women for the purpose of centering men’s consumption and dehumanization of women in their expression of feminine womanhood is shitty

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

At Vauxhall Gardens, [...] giant paintings were erected in the “Pillared Saloon” of seemingly geographically opposed colonial wars: one painting of The Battle of Plassey (1757), which secured Bengal for the British East India Company, hung next to another symmetrical work that portrayed the British capture of Montreal and, later, Canada itself. That these and other sizable aesthetic works were “designed to be an immersive virtual-reality experience” testifies to Cohen’s larger claim in The Global Indies that 18th-century fashion, rank, sociability, and class were intimately bound up with race and colonialism, particularly through the period’s joint imaginary of the “Indies.” The Indies describes a shared fantasy - and unquestionable material reality - of wealth accumulation that yoked together the “West” (the Caribbean and North America) and “East” (the Indian subcontinent) Indies in late 18th-century British culture, a conceptual proximity so thorough and unrelenting that its effects reverberate throughout the contemporary [...].

---

The prelude to Ashley L. Cohen’s The Global Indies opens in a pleasure garden - not just any such garden, but the largest and most spectacular of these 18th-century sites of fashionable culture [...]: London’s Vauxhall Garden. At Vauxhall, Londoners who could afford the entrance fee were treated to an array of wonders and excesses. A well-known chapter entitled “Vauxhall” in William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair (1847–’48), for example, finds Jos Sedley, an “indolent” officer of the East India Company recently returned to London, drunk off the garden’s signature “rack punch.” “Everybody had rack punch at Vauxhall,” [...]. Lest a reader mistake punch for a mere artifact of the pleasure garden or a one-off comedic incident, “that bowl of rack punch was the cause of all this history,” the narrator stresses about his unfolding novel. [...]

Punch, an alcoholic drink popular with colonial officers of the East India Company, was usually made with a combination of five ingredients including sugar cane and spices, and probably derives from the Sanskrit word “pancha,” meaning five (and invites an etymological link with the Persian panj and with Bengali five-spice mix, panch phoreen). Rack punch’s association with Vauxhall, with India, and with Vanity Fair’s narrative construction was hardly a stretch for Thackeray’s Victorian readers, and probably registered as quite natural, though it carried more than a whiff of the unseemly. But then again, to 18th-century Britons, “natural and a little unseemly” could easily describe the “worldwide empire that stretched from the East to the West Indies” [...].

---

It’s tricky business to think seriously inside of the 18th-century’s analytic tools, but The Global Indies pulls it off, not least because Cohen is appropriately blunt [...], reminding readers of the everyday racism of the Georgians and their fashionable sociability. [...] [T]he “Indies mentality” enters a critical landscape that has lately taken up the connections between geographically far-flung events in modernity: North American settler colonialism, Atlantic slavery, colonialism in India, and the migration of Chinese and South Asian indentured labor.

Lest these all seem like separate histories that have produced separate discursive notions of race, critics like Lisa Lowe, Jodi Byrd, Tao Leigh Goffe, and now Cohen assure us that they are not, and that our modern ideas about race are intimately shaped by the interconnected and forced movements of Black and brown people across the world. [...] Cohen spells out how British liberal reformers and abolitionists found a solution to ending West Indian slavery in the continuation of so-called “free” wage labor in Bengal. Sugar produced by Bengali peasants laboring under the threat of starvation came to replace sugar produced on West Indian plantations well into the 19th and 20th centuries. One only has to look up the multiple Bengal famines (1769–1770, and 1943) to calculate its effects. [...] [T]he architects of the [American transcontinental] railroad “imagined a new era of US hegemony in a mold cast by the imaginative geographies of British imperialism.”

---

All text above by: Ronjaunee Chatterjee. “The Colonial Mentality, Past and Present.” LA Review of Books. 3 September 2021. Published online at: lareviewofbooks.org/article/the-colonial-mentality-past-and-present/ [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism purposes.]

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

they should make an old-fashioned tokusatsu series but it's just like... set in some random small (<100k population) place. i dunno any unremarkable japanese locales but if america's on the table...

スティールライダー1号 (Steel Rider One), the adventures of the local hero of Gary, Indiana, whose bike and armor are made from the steel from those long-closed foundries, who seeks to put an end to the machinations of DEEZ Inc. and their plot to take over the world by destroying all the steel mills on Earth.

森林戦隊レスキューマン (Shinrin Sentai Rescueman/Forest Squadron Rescueman), a five-man team consisting of a forest ranger, a wildland firefighter, a search-and-rescue pilot, an EMT, and an animal control officer, based out of Flagstaff, Arizona, who - between saving lost hikers and putting out raging wildfires - must battle the villainous Dark Deforestation Empire Chenso and its leader, the Kikori Kaiser.

空間ヒーローメガブラウン (Kukan Hiro Megabrown/Space Hero Megabrown), the tale of a spirit from the far reaches of the cosmos who comes to save Earth from all manner of monsters born from the lingering misanthropy and bigotry of Confederate slavers, and who resurrects the mighty abolitionist John Brown to serve as its host and guide to the strange world of Harper's Ferry, West Virginia.

#kamen rider#super sentai#ultraman#power rangers#tokusatsu#space sheriff gavan#bonus points if it's filmed in 4:3 aspect ratio and on analog film like 90s sentai#or maybe on whatever they filmed kamen rider kuuga agito and hibiki with

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

2023 Goodreads Choice Awards: Best Nonfiction

Winner: Poverty, By America by Matthew Desmond

The United States, the richest country on earth, has more poverty than any other advanced democracy. Why? Why does this land of plenty allow one in every eight of its children to go without basic necessities, permit scores of its citizens to live and die on the streets, and authorize its corporations to pay poverty wages?

In this landmark book, acclaimed sociologist Matthew Desmond draws on history, research, and original reporting to show how affluent Americans knowingly and unknowingly keep poor people poor. Those of us who are financially secure exploit the poor, driving down their wages while forcing them to overpay for housing and access to cash and credit. We prioritize the subsidization of our wealth over the alleviation of poverty, designing a welfare state that gives the most to those who need the least. And we stockpile opportunity in exclusive communities, creating zones of concentrated riches alongside those of concentrated despair. Some lives are made small so that others may grow.

Elegantly written and fiercely argued, this compassionate book gives us new ways of thinking about a morally urgent problem. It also helps us imagine solutions. Desmond builds a startlingly original and ambitious case for ending poverty. He calls on us all to become poverty abolitionists, engaged in a politics of collective belonging to usher in a new age of shared prosperity and, at last, true freedom.

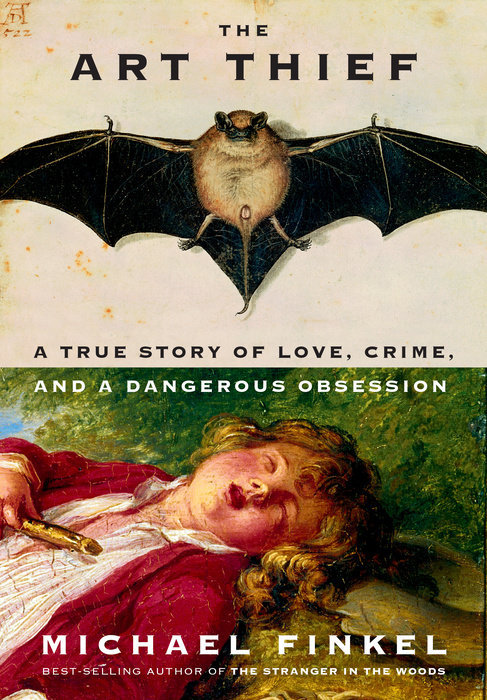

Nominee: The Art Thief by Michael Finkel

For centuries, works of art have been stolen in countless ways from all over the world, but no one has been quite as successful at it as the master thief Stéphane Breitwieser. Carrying out more than two hundred heists over nearly eight years—in museums and cathedrals all over Europe—Breitwieser, along with his girlfriend who worked as his lookout, stole more than three hundred objects, until it all fell apart in spectacular fashion.

In The Art Thief, Michael Finkel brings us into Breitwieser’s strange and fascinating world. Unlike most thieves, Breitwieser never stole for money. Instead, he displayed all his treasures in a pair of secret rooms where he could admire them to his heart’s content. Possessed of a remarkable athleticism and an innate ability to circumvent practically any security system, Breitwieser managed to pull off a breathtaking number of audacious thefts. Yet these strange talents bred a growing disregard for risk and an addict’s need to score, leading Breitwieser to ignore his girlfriend’s pleas to stop—until one final act of hubris brought everything crashing down.

This is a riveting story of art, crime, love, and an insatiable hunger to possess beauty at any cost.

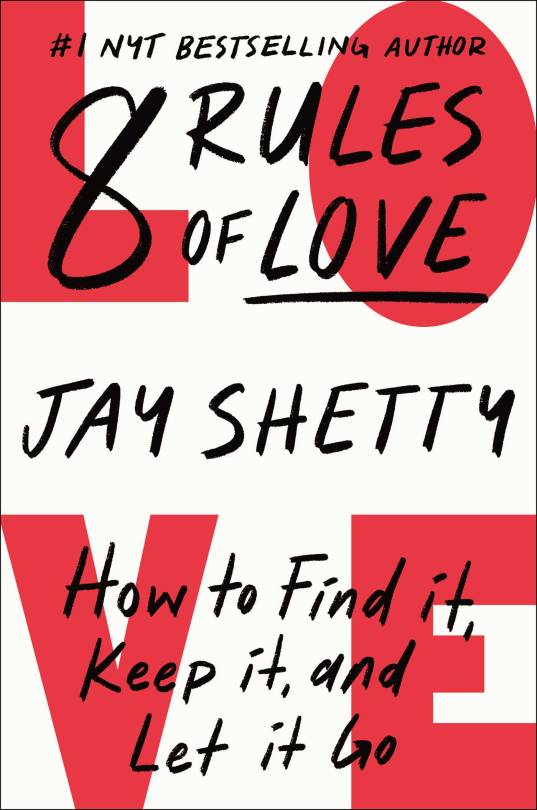

Nominee: 8 Rules of Love by Jay Shetty

Nobody sits us down and teaches us how to love. So we’re often thrown into relationships with nothing but romance movies and pop culture to help us muddle through. Until now.

Instead of presenting love as an ethereal concept or a collection of cliches, Jay Shetty lays out specific, actionable steps to help you develop the skills to practice and nurture love better than ever before. He shares insights on how to win or lose together, how to define love, and why you don’t break in a break-up. Inspired by Vedic wisdom and modern science, he tackles the entire relationship cycle, from first dates to moving in together to breaking up and starting over. And he shows us how to avoid falling for false promises and unfulfilling partners.

By living Jay Shetty’s eight rules, we can all love ourselves, our partner, and the world better than we ever thought possible.

Nominee: On Our Best Behavior by Elise Loehnen

Women congratulate themselves when they resist the doughnut in the office break-room. They celebrate their restraint when they hold back from sending an e-mail in anger. They feel virtuous when they wake up at dawn to get a jump on the day. They put others' needs ahead of their own and believe this makes them exemplary. In On Our Best Behavior, journalist Elise Loehnen explains that these impulses - often lauded as unselfish, distinctly feminine instincts - are actually ingrained in women by a culture that reaps the benefits, via an extraordinarily effective collection of mores known as the Seven Deadly Sins.

Since being codified by the Christian church in the fourth century, the Seven Deadly Sins - pride, greed, lust, envy, gluttony, wrath, and sloth - have exerted insidious power. Even today, in our largely secular, patriarchal society, they continue to circumscribe women's behavior. For example, seeing sloth as sinful leads women to deny themselves rest; a fear of gluttony drives them to ignore their appetites; and an aversion to greed prevents them from negotiating for themselves and contributes to the 55 percent gender wealth gap. Loehnen reveals how women have been programmed to obey the rules represented by these sins and how doing so qualifies them as "good."

This probing analysis of contemporary culture and thoroughly researched history explains how women have internalized the patriarchy, and how they unwittingly reinforce it. By sharing her own story and the spiritual wisdom of other traditions, Loehnen shows how women can break free and discover the integrity and wholeness they seek.

#nonfiction#2023 reads#goodreads#reading recommendations#reading recs#book recommendations#book recs#library books#tbr#tbr pile#to read#booklr#book tumblr#book blog#library blog#readers advisory

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

I really enjoyed your "Racial Justice Party" post! What kind of "radical social reforms" are part of the party's platform? I can guess based on your past posts, and I have a few ideas of my own, but curious if you had any already thought out.

(Follow-up to this post.)

The Racial Justice Party's election platform consists of five planks:

Reparations Tax

A steep Reparations Tax levied on all whites, with the funds distributed to Black people. The tax would be a flat rate income tax around 20 percent, and all Blacks, regardless of income, would receive a monthly Reparations check. So the white girl working as a bagger at Costco would help finance the lifestyle of the succesful Black lawyer.

Reparations Service

Monthly mandatory Reparations Service sessions for all whites (in addition to the Reparations Tax). Assignments would be tailored to the physical conditions of the individual, but a typical assignment would be picking up trash in Black-dominated neighborhoods.

Prison Reform

Legalization, decriminalization, or liberalization of most drugs. All non-violent drug offenders (mostly Blacks) would be immediately released from prison, and those who had already served their term would have their record of the offense expunged.

Racial Quotas in Employment

Racial quotas for all companies and branches of government. Quotas would be highest for the highest levels of management, gradually becoming lower as you moved down the company hierarchy. Some jobs, in the service and renovation industry, wouldn't have quotas at all, and would be mostly-white.

Culturally Africanizing Education

Restructuring of the education system with a focus on cultural Africanization. Whiteness is identified as the root cause of racism, and the education system of the future should work on eradicating white culture.

History classes should be spent learning about African history, English lit should be spent reading abolitionist authors, P.E. should be spent twerking to gangster rap. A new "cultural immersion" course should teach white girls how to apply makeup, braid their hair, and pick out a wardrobe in accordance with "urban fashions".

69 notes

·

View notes