#abolitionist literature

Text

"What does he know of the half-starved wreaths toiling from dawn till dark on the plantations? of mothers shrieking for their children, torn from their arms by slave traders? of young girls dragged down into moral filth? of pools of blood around the whipping post? of hounds trained to tear human flesh? of men screwed into cotton gins to die?"

Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

#incidents in the life of a slave girl#harriet jacobs#slavery#american slavery#abolition of slavery#abolitionist#liberation#liberty#freedom#racism#racism in america#human rights violations#human rights abuses#poc#black academia#black feminism#black liberation#american authors#american literature#literature#literature quotes#race theory#race and gender#race and ethnicity

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm gonna go out on a limb here and say it's actually a bit disingenuous to say that america, as it exists today, is not in any way a christian nation. it's true that it is not legally a christian nation, that its political bodies were not intended to be theocratic and that the concept of religious freedom and separation of church and state are intrinsic to the constitution. it should never have an official religion, least of all christianity.

but I mean. let's be honest with ourselves. there is no religion more thoroughly baked into american culture than christianity. it's everywhere, and has been everywhere since the colonial period. you see it in our music, you see it in our literature and films, it's in our holidays and customs and cultural practices. and it is in politics, whether we like it or not (and trust me, I do not.)

this is what people mean when they talk about cultural christianity in the us. there's no way around it- even if you yourself are not christian and/or have never been christian, you're surrounded by it. you're going to encounter it, you're going to see it, you might even be influenced by it. if nothing else, you will have to contend with it and you will have to contend with its influence on broader american culture. you just will.

I don't think it helps discourse to deny reality. separation of church and state is essential to maintain and religious freedom must be preserved and protected, religion should have no place in government as the founders intended, and...america is predominantly a culturally christian nation.

#...this post was inspired by of all things an instagram reel parodying battle hymn of the republic#but that particular song is a perfect microcosm of my point here#the song was written in the context of the american civil war#it's a patriotic song#written by an abolitionist#it's about a very specific historical and cultural time period and yet it has survived in the american cultural lexicon to this day#the song is referenced in the title of grapes of wrath which is a seminal piece of american literature#you've seen and heard it parodied and referenced a thousand times#it's played at inaugurations and important political events and sometimes sports games#it's used in movies and tv#I promise you that you know battle hymn of the republic if you grew up here#and what is the most famous lyric that isn't the refrain?#“as he died to make men holy let us die to make men free”#it's a fucking reference to jesus#I mean the whole song is religious#that is the definition of cultural christianity

1 note

·

View note

Text

“To suppress free speech is a double wrong. It violates the rights of the hearer as well as those of the speaker.” #quote #frederickdouglas #frederickdouglasquote

Frederick Douglas“To suppress free speech is a double wrong. It violates the rights of the hearer as well as those of the speaker.”Read this amazing autobiography by Frederick Douglas.Source: Gutenberg.org

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

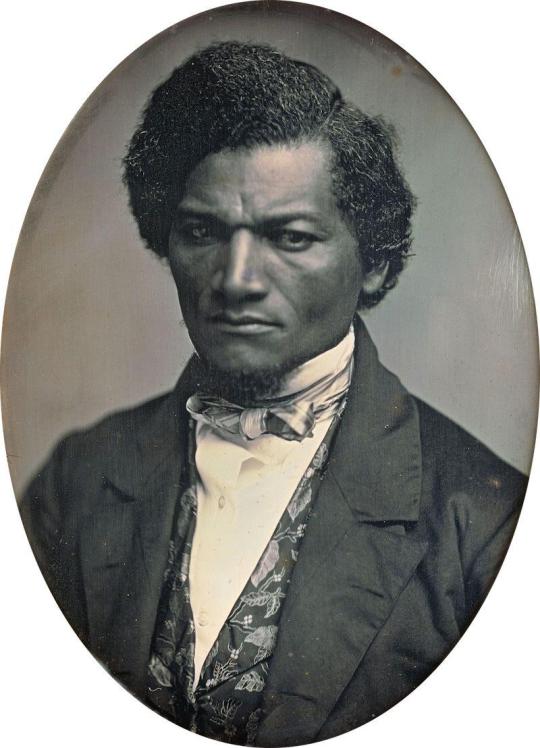

Photo

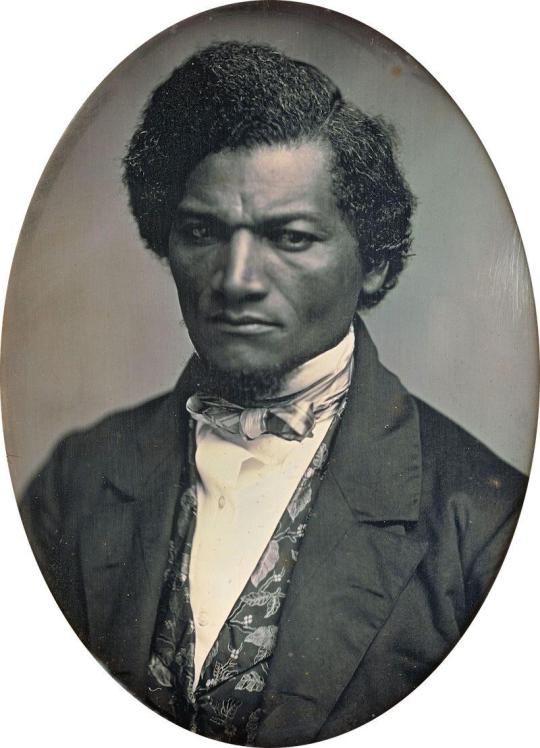

Abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass died #onthisday in 1895, aged 77. Read his only published work of fiction "The Heroic Slave", first featured in Autographs for Freedom, an anthology of anti-slavery literature published in 1853: https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/autographs-for-freedom-1853 #otd

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

September 2023 reading

Books:

Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

Dennis Cooper, The Sluts

Vladimir Mayakovsky, Volodya: Selected Works, ed. Rosy Carrick

Vincent Woodard, The Delectable Negro: Human Consumption and Homoeroticism Within US Slave Culture

Articles, papers, etc.:

S. Brook Corfman, Yentl and the Three-Quarter Profile

Catherine Damman and Saidiya Hartman, Saidiya Hartman on insurgent histories and the abolitionist imaginary

Jules Gill-Peterson, The Way We Weren't

killreplica, Heidegger's Broken Doll

Julian Lucas, How Samuel R. Delaney Reimagined Sci-Fi, Sex, and the City

Max Pensky, Angel of Mystery: The tangled story behind a famous Klee painting

Gloria Goodwin Raheja, Caste, Colonialism, and the Speech of the Colonized: Entextualization and Disciplinary Control in India

Achim Rohde, Gays, Crossdressers, and Emos: non-normative masculinities in militarized Iraq

Dylan Saba, Review: 'On Zionist Literature' by Ghassan Kanafani

Leo Zeilig, The Dar es Salaam Years

#reading#all the books are bolded bc it was a banger month for books hth#honest 2 god though i spend 90% of my free time on gay little visual novels atp

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

As early as 1700, Samuel Sewall, the renowned Boston judge and diarist, connected “the two most dominant moral questions of that moment: the rapid rise of the slave trade and the support of global piracy” in many American colonies [...]. In the course of the eighteenth century, [...] [there was a] semantic shift in the [literary] trope of piracy in the Atlantic context, turning its [...] connotations from exploration and adventure to slavery and exploitation. [...] [A] large share of Atlantic seafaring took place in the service of the circum-Atlantic slave trade, serving European empire-building in the Americas. [...] Ships have been cast as important sites of struggle and as symbols of escape in [...] Black Atlantic consciousness, from Olaudah Equiano’s Interesting Narrative (1789) and Richard Hildreth’s The Slave: or Memoir of Archy Moore (1836 [...]) to nineteenth century Atlantic abolitionist literature such as Frederick Douglass’s My Bondage and My Freedom (1855) or Martin Delany’s Blake (1859-1862). [...] Black and white abolitionists across the Atlantic world were imagining a different social order revolving around issues of resistance, liberty, (human) property, and (il)legality [...].

---

Using black pirates as figures of resistance [...], Maxwell Philip’s novel Emmanuel Appadocca (1854) emphasizes the nexus of insatiable material desire and its conditions of production: slavery. [...] [T]he consumption of commodities produced by slave labor itself was delegitimized [...]. Philip, a Trinidadian [and "illegitimate" "colored" child] [...], published Emmanuel Appadocca as a protest against slavery in the United States [following the Fugitive Slave laws of 1850.]. [...] [The novel places] at its center [...] a heroic non-white pirate and intellectual [...] [whose] pirate ship [...] [is] significantly named The Black Schooner [...]. One of the central discourses in [the book] is that of legitimacy, of rights and lawfulness, of both slavery and piracy [...]. About midway into the book, Appadocca gives a [...] speech in which he argues that colonialism itself is a piratical system:

If I am guilty of piracy, you, too [are] [...] guilty of the very same crime. ... [T]he whole of the civilized world turns, exists, and grows enormous on the licensed system of robbing and thieving, which you seem to criminate so much ... The people which a convenient position ... first consolidated, developed, and enriched, ... sends forth its numerous and powerful ships to scour the seas, the penetrate into unknown regions, where discovering new and rich countries, they, in the name of civilization, first open an intercourse with the peaceful and contented inhabitants, next contrive to provoke a quarrel, which always terminates in a war that leaves them the conquerors and possessors of the land. ... [T]he straggling [...] portions of a certain race [...] are chosen. The coasts of the country on which nature has placed them, are immediately lined with ships of acquisitive voyagers, who kidnap and tear them away [...].

In this [...], slavery appears as a direct consequence of the colonial venture encompassing the entire “civilized world,” and “powerful ships” - the narrator refers to the slavers here - are this world’s empire builders. [...] Piracy, for Philip, signifies a just rebellion, a private, legitimate [resistance] against colonial exploiters and economic inequality - he repeatedly invokes their solidarity as misfortunate outcasts [...].

---

All text above by: Alexandra Ganser. “Cultural Constructions of Piracy During the Crisis Over Slavery.” A chapter from Crisis and Legitimacy in the Atlantic American Narratives of Piracy: 1678-1865. Published 2020. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me.]

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

rubynye replied to this post:

Olaudah Equiano: enslaved as a child, bought his own freedom, campaigned eloquently for abolition, his memoir went through nine printings at least. An erudite Black man from before many people think Black people were invented. I can't adequately express how happy seeing him in your list made me.

Equiano is a truly fascinating, compelling figure. His memoir was assigned in a grad school seminar I took on 18th-century British literature focused on various forms of resistance and dialogue among/between/about the oppressed, and it was really intriguing to read abolitionist poetry and tracts mainly by white English people across the political spectrum of their era and then Equiano's Interesting Narrative. The contrast is incredible.

He's in my dissertation for basically one passage—the account of his capture and lifelong separation from his sister. But it's a hell of a passage.

(Now that I'm thinking about it, he was also in the curriculum I designed when I took over my advisor's upper-division 18th-century class for a semester, and my undergrad students loved the Interesting Narrative, way more than the grad students in my own seminar had. Most of my students had no idea he'd even existed and they just really got into it.)

#rubynye#respuestas#olaudah equiano#eighteenth century blogging#ivory tower blogging#cw slavery#the interesting narrative of the life of olaudah equiano#nice things people say to me

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chain Gang All-Stars

Great book.

I sort of hope Chain Gang All-Stars is never adapted into a show or movie. It’s certainly possible that it could be done with proper deference to the tone and message of the book, but I think it’s far more likely that it would end up essentially being what Chain Gang is in the story itself - a hyper-violent spectacle that people tune into because they think it’s cool and action-packed. I think Chain Gang All-Stars is very successful at walking the tightrope line of drawing the reader into the story and letting them flirt with what it must feel like to be a viewer of the program, while presenting enough reminders of its grim reality to prevent you from being totally sucked in. While there were times during the LinkLyfe segments where I was drawn in the way a viewer absorbed in a reality show would be, the battles themselves never give in to ‘just’ being badass. They were tense, certainly, and I was on pins & needles reading them, worried about the characters, but there’s a certain utilitarian brutality to the writing in those sections that keeps them grounded. I’d be worried any adaptation would make everything too stylish and exciting, thoroughly missing the point*.

*To say nothing of any potential dilution of the politics to appeal to a wider audience.

—

“All other sport was just a metaphor for this.”

—

Chain Gang All-Stars is incredibly good at giving every single character a depth and fullness, even ‘antagonists’, so that even the characters who infuriate us, we understand to a degree. The book doesn't justify evil deeds - there’s no excusing Wil’s dumb ass self - but it shows how easy it is for someone to placate themselves, to keep themselves on a surface level and not dig too deep into their own morality, to convince themselves that they’ve done what they could and that all those who have wrong done to them deserve what they get. The fluid perspective switches it accomplishes this with are fascinating, too. We get chapters dedicated to different characters, of course, be it our leads, our deuteragonists, and plenty of one-off side stories - standard stuff. But Adjei-Brenyah also rapidly switches between multiple perspectives within the same page, hell, the same paragraph at times, which gives us insight into a much wider breadth of viewpoints than we normally would.

By getting to see into the inner thoughts of quite a few Links, we get to see how, while their individual experiences are different, their imprisonment has broken them all in tragically similar ways. From Bishop to Sunset to Thurwar to Staxxx, we see a consistent, crippling lack of self-worth. The A-Hamm chain is unique in preaching a vision of solidarity, accepting one’s past mistakes, and focusing on how they’ve grown and changed as people. Despite this, at their core, none of them can truly find it in themselves to be forgiven, because Chain Gang grinds their lack of perceived value into them unceasingly - ultimately resulting in what is essentially suicide. The carceral system does not allow for or encourage rehabilitation, only suffering and self-hatred.

I thought it was a compelling decision to make the majority of the imprisoned characters we follow legitimate violent offenders. A lot of the abolitionist / prison-critical literature I’ve read often focuses on, or at least begins with, incarceration that is plainly, nakedly unjust, like long-serving non-violent offenders and mandatory minimum sentencing. Conversations about the treatment of murderers, rapists, etc., are naturally more fraught - it’s harder to get someone to imagine an entirely different system, rather than just adjustments to the current system.

Chain Gang All-Stars does not shy away from it one bit. We get self-reflection from multiple different Links, both those who regret what they’ve done and those who don’t; we get conflicted thoughts from family members who recognize that their lives have been fundamentally changed by the imprisonment of their kin, but are still ambivalent about forgiveness; and we get, of course, the fearmongering and appeals to pathos used by government and the media to try and stop any ideas of abolition from even beginning to take root in the minds of the public. The book understands that there’s no easy answers, and instead brings all of these perspectives to the reader, demanding they grapple with the issues themselves.

It does, however, make clear the absurdity of pretending that taking someone whose life has been indelibly touched by violence and putting them into a system that encourages and requires additional violence, by the state, by their peers, is somehow rehabilitation. It’s brought to an extreme in the novel, of course - Thurwar’s overriding instinct that every problem can potentially be solved by violence due to the constant killing she’s done is more reminiscent of a soldier returning to peacetime than anything else - but the message stands.

Some of the most powerful parallels shine through as-is, though. Even when you put aside the horror the Links are put through on a daily basis and the rampant normalization of state-sanctioned violence, the base lack of freedom and personal autonomy is what breaks people. Both during Chain Gang and our looks at other prisons, the regimented days, planned schedule, and inability to spend time or talk with the people they care about are basic human rights that are removed from prisoners every day. Hendrix’s silent prison (an idea I was horrified to find has been enacted before) shows this in one extreme - after being robbed of something as simple as his own voice for so long, Hendrix is willing to risk everything just to be able to reclaim that part of himself.

Most heartbreakingly, the morning of the final doubles match, Thurwar’s only desire is to stay in bed longer with Staxxx. Leisure time with your loved ones, one of the most basic luxuries a person ought to have, seen as an unobtainable prize. Don’t need a dystopian near-future novel to see that happening.

Speaking of Hendrix Young, the voice Adjei-Brenyah uses for his sections was absolutely beautiful and oozing with character and I loved it. The way he speaks is simultaneously poetic yet so pragmatic - there’s an idiosyncratic turn of phrase in nearly every paragraph, and his love for the world and its beauty is never eclipsed by his cynicism and the horrible things happening around him. His sections were handily my favorites, despite the looming dramatic irony that overshadows them all.

—

“I thought of how the world can be anything and how sad it is that it’s this.”

—

As a literary device, the interspersing of worldbuilding notes and Actual Fucked-Up Prison Facts was a genius touch. By priming your brain to expect something more fantastical, the more grounded notes become something of a sucker punch. The first few are all in-universe lore explanations - they’re not entirely necessary, you could’ve pretty much got the gist through context, but the thorough explanation written almost as an ad read pulls you into the mentality of this world… so then, when it drops, say, the net worth and founding members of the Corrections Corporation of America and you get the inkling that this tidbit feels a little too specific to be made up, the lines between the book’s world and our own start to blur.

In addition to the unique cognitive dissonance it invokes, I think it’s a pretty effective strategy to convince or teach a reader who perhaps hasn’t done as much digging about the nightmare that is the American prison-industrial complex. Especially given that the main conceit of the book is a little outlandish, it’s very easy for me to imagine such a reader enjoying the story for its plot, but deflecting or doubting the themes with the classic “Oh, but this is an exaggeration - it would never happen like this! It would never be that sadistic”. In some way, the footnotes feel like the author directly responding with a “Yes, it would, and in fact has already happened this way previously”.

I do wish the footnotes stayed as dense throughout the entire book as they were at the start. In the beginning, they come hard and fast, blending the real and the fictional, keeping the reader on their toes. About a third of the way through, though, they slow to a trickle, becoming a rarity. Adjei-Brenyah keeps experimenting with what the footnotes can convey (“Don’t look down. Help me.” was particularly chilling), but the infrequency starts to make them feel like an afterthought.

—

“Just jump.”

—

The closer I got to the end of Chain Gang All-Stars, as fewer and fewer pages remained, I was increasingly desperate for something to break. Even as the story continued towards the inevitable, even as it showed me there could be no other way for things to go, I hoped for something else. Anything but what happened.

And yet… the ending gives this book’s message a lot of its power. It’s not a story where things always work out and the good guys always win - it’s a reflection of real problems, and those real problems don’t have such a simple solution. Chain Gang All-Stars is about people living in an unfair world, working within a cruel, unjust, system, and still finding the strength and conviction to believe that there can be positive change. It’s about knowing that progress can be slow, and that the system can feel daunting, and feeling powerless to enact change, and still imagining and pushing for the world to be better anyway. And somehow, that it faces that hopelessness head-on makes it more uplifting than a safer story with an easier ending.

#will's media thoughts / virtual brain repository#books#chain gang all stars#just for the sake of the journal i'll add#that reading this after rewatching the hunger games#only lowered my esteem of them even further lol

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

The strong presence of the sea is grossly under-examined in American literature, doubly so in African American literature. As Elizabeth Schultz observes, "Historically and culturally, the African American experience has been an inland one. Black Americans," she continues, "have not generally turned seaward in their literature." Although she comes to a "however" that adds the observation "the sea is not absent from African American literature," the rhetorical pose imagined in the claim that "the sea is not absent" is that it will take a good deal of searching to find it. And yet, as Jeffery Bolster observes in his ground-breaking 1997 study Black Jacks, "Sailors wrote the first six autobiographies of blacks published in English before 1800". Many of these autobiographies carry clear abolitionist intent and hint at the type of anti-slavery discussions carried on by sailors around the Atlantic world. When scholars of African American literature turn their attention to works written by sailors, like Olaudah Equiano's The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavas Vassa, the African. Written by Himself (1789), most suffer from the misplaced assumption Schultz points to, and thus fail to see the crucial link between sailors and black abolitionism. Indeed, what Crispus Attucks, Paul Cuffee, Robert Smalls, Frederick Douglass, and so many other black revolutionaries in America have in common is that they were all sailors or in some other way directly connected to the maritime trades.

— Matthew D. Brown, 2013. “Olaudah Equiano and the Sailor’s Telegraph: The Interesting Narrative and the Source of Black Abolitionism.” Callaloo: A Journal of African Diaspora Arts and Letters 36 (1): 191–201. doi:10.1353/cal.2013.0059 (Google Drive link)

‘Drunken Sailors’ by John Locker, 1829 (NMM)

#age of sail#black history#black sailors#sailors#naval history#maritime history#atlantic world#abolitionism#black jacks#olaudah equiano#john locker#maritime art#black history month

178 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm kinda new to the abolitionist movement and I'm curious as to how it looks at people who actually do commit sex crimes (rape, molestation etc.) and what the plan is for handling them. I always assumed it was to separate them from society but still treat them with dignity but I'm still kinda doing my research. What's your take on it? How do we help these people and re-integrate them into society without risking them harming others?

the thing about abolitionism, as with most facets of anarchist philosophy, is that while we develop accurate and strong criticisms of the systems that are currently in place, we obviously do not have the perfect and immutable answers for what should replace these systems. clearly the american carceral system is corrupt, antithetical to its intended goal of reducing crime, and a tragedy against human rights. it is built on imperial, racist and classist foundations, and as the rot is foundational the system cannot be fixed from the inside.

as for what should replace it, the answer i think every anarchist can agree with is "something else". and, should that other thing prove to be inhumane, corrupt, prejudiced, and/or otherwise dysfunctional, it must be opposed and either fixed or else replaced itself.

you ask what my ideal process is for dealing with people who commit ('bad' or violent) sex crimes. i have met several people who fit this description, and each one was only able to reform and come to regret their actions after finding resources such as an understanding community, psychological help for past trauma, and grace that allowed them to re-integrate into society as a reformed person.

therefore, my answer to you is that the 'solution' is most likely holistic. people tend to not commit violent crimes in the first place when they are part of a positive and understanding community. people tend to not commit sexual crimes when they have a comprehensive education re: consent and sex. people tend to regret their past actions with the right support and education.

i am sure that you can find plenty of literature on the subject if you go looking. i hope that this helps!

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

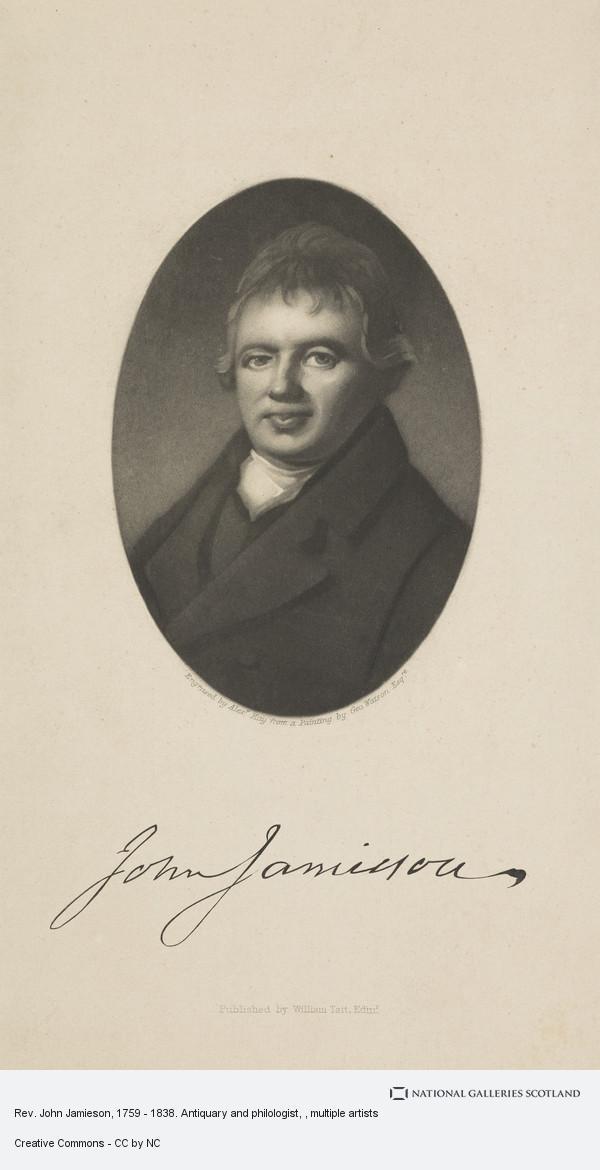

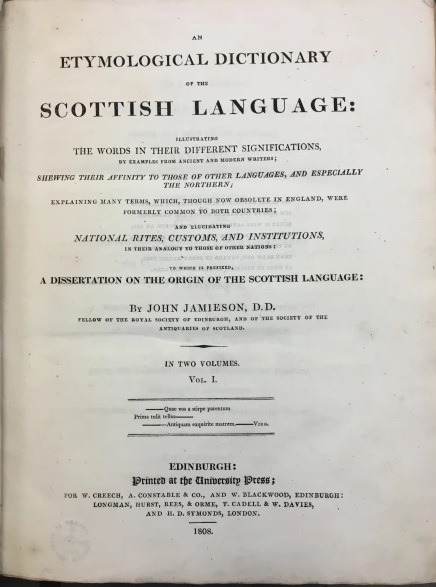

On March 5th 1759 the lexicographer and church minister John Jamieson was born in Glasgow.

I know most of you will not have heard of Jamieson, but his publication, Etymological Dictionary of the Scottish Language, is credited with keeping the language alive. He was a bit of a polymath though and learned in many fields.

The language I am talking about here is Scots, the Scot’s Tongue as it is often referred to, If you have read some of my posts I like to dig out documents etc from days gone by, a most of these are written in Scots, you only have to read the poetry of Robert Fergusson or Rabbie Burns, the vast majority which is written in the language, or up to modern times if you have read any of Irvine Welsh’s books, you will know that as a language it is distinctly different to what is termed as “proper English”

Anyway a bit about the man, Jamieson grew up in Glasgow as the only surviving son in a family with an invalid father, he entered Glasgow University aged at the staggeringly young age of just nine! From 1773 he studied the necessary course in theology with the Associate Presbytery of Glasgow, and in 1780 he was licensed to preach.

Jamieson was appointed to serve as minister to the newly established Secession congregation in Forfar, and stayed there for the next eighteen years, during which time he married Charlotte Watson, the daughter of a local widower, and started a family. Their marriage lasted fifty-five years and they had seventeen children, ten of whom reached adulthood, although only three outlived their father. He next became minister of the Edinburgh Nicolson Street congregation in 1797 where he guided the reconciliation of the Burgher and Anti-Burgher sects to a union in 1820.

In 1788 Jamieson’s writing was recognised by Princeton College, New Jersey where he received the degree of Doctor of Divinity. His other honours included membership of the Society of Scottish Antiquaries, of the Royal Physical Society of Edinburgh, of the American Antiquarian Society of Boston, United States, and of the Copenhagen Society of Northern Literature. He was also a royal associate of the first class of the Royal Society of Literature instituted by George IV.

Jamieson’s chief work, the Etymological Dictionary of the Scottish Language was published in two volumes in 1808 and was the standard reference work on the subject until the publication of the Scottish National Dictionary in 1931. He published several other works, but it is the dictionary he is best known for.

He had a particular passion for numismatics, and it was their mutual interest in coins which led to the first meeting between Jamieson and Walter Scott, in 1795, when Scott was only twenty-three and not yet a published author. Jamieson was also a keen angler, as the many entries relating to fishing terms in the Dictionary attest; and published occasional works of poetry, including a poem against the slave trade which was praised by abolitionists in its day. Entries provided by Scott include besom, which he described as a “low woman or prostitute,” and screed, defined as a “long revel” or “hearty drinking bout”. I wonder how many Scottish females have been called “a wee besom” by their mothers with neither really knowing it’s true meaning!

Jamieson’s association with Walter Scott was a two way thing, he wrote a Scots poem ‘The Water Kelpie’ for the second edition of Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border.

It was through his antiquarian research that Jamieson developed his practice of tracing words (particularly place-names) to their earliest form and occurrence: a method which was to be the foundation of the historical approach he would use in the Dictionary.

Jamieson wrote on other themes: rhetoric, cremation, and the royal palaces of Scotland, besides publishing occasional sermons. In 1820 he issued edited versions of Barbour’s The Brus and Blind Harry’s Wallace.

Revered by authors including Hugh MacDiarmid, who used it to shape his poetic output, Jamieson’s dictionary has long been regarded as a crucial groundwork which kept alive the Scots language at a time when it was in danger of falling into obscurity.

John Jamieson died on July 22nd 1839 and has a fine gravestone in St Cuthbert’s graveyard in Edinburgh, as seen in the fourth pic.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

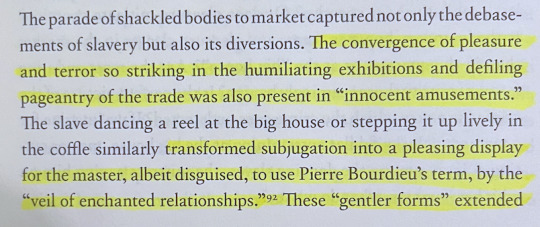

[ID: The parade of shackled bodies to market captured not only the debasements of slavery but also its diversions. The convergence of pleasure and terror so striking in the humiliating exhibitions and defiling pageantry of the trade was also present in “innocent amusements.” The slave dancing a reel at the big house or stepping it up lively in the coffle similarly transformed subjugation into a pleasing display for the master, albeit disguised, to use Pierre Bourdieu’s term, by the “veil of enchanted relationships.” These “gentler forms” extended and maintained the relations of domination through euphemism and concealment. Innocent amusements constituted a form of symbolic violence — that is, a “form of domination which is exercised through the communication in which it is disguised.”

When viewed in this light, the most invasive forms of slavery’s violence lie not in these exhibitions of “extreme” suffering or in what we see, but in what we don’t see. Shocking displays too easily obfuscate the more mundane and socially endurable forms of terror. In the benign scenes of plantation life (which comprised much of the Southern and, ironically, abolitionist literature of slavery) reciprocity and recreation obscure the quotidian routine of violence. The bucolic scenes of plantation life and the innocent amusements of the enslaved, contrary to our expectations, succeeded not in lessening terror but in assuring and sustaining its presence.

Rather than glance at the most striking spectacle with revulsion or through tear-filled eyes, we do better to cast our glance at the more mundane displays of power and the border where it is difficult to discern domination from recreation. Bold instances of cruelty are too easily acknowledged and forgotten, and cries quieted to an endurable hum. By disassembling the “benign” scene, we confront the everyday practice of domination, the daily routine of terror, the nonevent, as it were. Is the scene of slaves dancing and fiddling for their masters any less inhumane than that of slaves sobbing and dancing on the auction block? If so, why? Is the effect of power any less prohibitive? Or coercive? Or does pleasure mitigate coercion? Is the boundary between terror and pleasure clearer in the market than in the quarters or at the “big house”? Are the most enduring forms of cruelty those seemingly benign? Is the perfect picture of the crime the one in which the crime goes undetected? If we imagine for a moment a dusky fiddler entertaining at the big house, master cutting a figure among the dancing slaves, the mistress egging him on with her laughter, what do we see? end ID]

saidiya hartman, scenes of subjection

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Knowledge makes a man unfit to be a slave.” #quote #frederickdouglas #frederickdouglasquote

Frederick Douglas“Knowledge makes a man unfit to be a slave.”Read this amazing autobiography by Frederick Douglas.Source: Gutenberg.org

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass died #onthisday in 1895, aged 77. Read his only published work of fiction "The Heroic Slave", first featured in Autographs for Freedom, an anthology of anti-slavery literature published in 1853: https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/autographs-for-freedom-1853 #otd

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coral today is an icon of environmental crisis, its disappearance from the world’s oceans an emblem for the richness of forms and habitats either lost to us or at risk. Yet, as Michelle Currie Navakas shows in her eloquent book, Coral Lives: Literature, Labor, and the Making of America, our accounts today of coral as beauty, loss, and precarious future depend on an inherited language from the nineteenth century. [...] Navakas traces how coral became the material with which writers, poets, and artists debated community, labor, and polity in the United States.

The coral reef produced a compelling teleological vision of the nation: just as the minute coral “insect,” working invisibly under the waves, built immense structures that accumulated through efforts of countless others, living and dead, so the nation’s developing form depended on the countless workers whose individuality was almost impossible to detect. This identification of coral with human communities, Navakas shows, was not only revisited but also revised and challenged throughout the century. Coral had a global biography, a history as currency and ornament that linked it to the violence of slavery. It was also already a talisman - readymade for a modern symbol [...]. Not least, for nineteenth-century readers in the United States, it was also an artifact of knowledge and discovery, with coral fans and branches brought back from the Pacific and Indian Oceans to sit in American parlors and museums. [...]

---

[W]ith material culture analysis, [...] [there are] three common early American coral artifacts, familiar objects that made coral as a substance much more familiar to the nineteenth century than today: red coral beads for jewelry, the coral teething toy, and the natural history specimen. This chapter is a visual tour de force, bringing together a fascinating range of representations of coral in nineteenth-century painting and sculptures.

With the material presence of coral firmly in place, Navakas returns us to its place in texts as metaphor for labor, with close readings of poetry and ephemeral literature up to the Civil War era. [...] [Navakas] includes an intriguing examination of the posthumous reputation of the eighteenth-century French naturalist Jean-André Peyssonnel who first claimed that coral should be classed as an animal (or “insect”), not plant. Navakas then [...] considers white reformers, both male and female, and Black authors and activists, including James McCune Smith and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, and a singular Black charitable association in Cleveland, Ohio, at the end of the century, called the Coral Builders’ Society. [...]

---

Most strikingly, her attention to layered knowledge allows her to examine the subversions of coral imagery that arose [...]. Obviously, the mid-nineteenth-century poems that lauded coral as a metaphor for laboring men who raised solid structures for a collective future also sought to naturalize a system that kept some kinds of labor and some kinds of people firmly pressed beneath the surface. Coral’s biography, she notes, was “inseparable from colonial violence at almost every turn” (p. 7). Yet coral was also part of the material history of the Black Atlantic: red coral beads were currency [...].

Thus, a children’s Christmas story, “The Story of a Coral Bracelet” (1861), written by a West Indian writer, Sophy Moody, described the coral trade in the structure of a slave narrative. [...] In addition, coral’s protean shapes and ambiguity - rock, plant, or animal? - gave Americans a model for the difficulty of defining essential qualities from surface appearance, a message that troubled biological essentialists but attracted abolitionists. Navakas thus repeatedly brings into view the racialized and gendered meanings of coral [...].

---

Some readers from the blue humanities will want more attention, for example, to [...] different oceans [...]: Navakas’s gaze is clearly eastward to the Atlantic and Mediterranean and (to a degree) to the Caribbean. Many of her sources keep her to the northern and southeastern United States and its vision of America, even though much of the natural historical explorations, not to mention the missionary interest in coral islands, turns decidedly to the Pacific. [...] First, under my hat as a historian of science, I note [...] [that] [q]uestions about the structure of coral islands among naturalists for the rest of the century pitted supporters of Darwinian evolutionary theory against his opponents [...]. These disputes surely sustained the liveliness of coral - its teleology and its ambiguities - in popular American literature. [...]

My second desire, from the standpoint of Victorian studies, is for a more specific account of religious traditions and coral. While Navakas identifies many writers of coral poetry and fables, both British and American, as “evangelical,” she avoids detailed analysis of the theological context that would be relevant, such as the millennial fascination with chaos and reconstruction and the intense Anglo-American missionary interest in the Pacific. [...] [However] reasons for this move are quickly apparent. First, her focus on coral as an icon that enabled explicit discussion of labor and community means that she takes the more familiar arguments connecting natural history and Christianity in this period as a given. [...] Coral, she argues, is most significant as an object of/in translation, mediating across the Black Atlantic and between many particular cultures. These critical strategies are easy to understand and accept, and yet the word - the script, in her terms - that I kept waiting for her to take up was “monuments”: a favorite nineteenth-century description of coral.

Navakas does often refer to the awareness of coral “temporalities” - how coral served as metaphor for the bridges between past, present, and future. Yet the way that a coral reef was understood as a literal graveyard, in an age that made death practices and new forms of cemeteries so vital a part of social and civic bonds, seems to deserve a place in this study. These are a greedy reader’s questions, wanting more. As Navakas notes in a thoughtful coda, the method of the environmental humanities is to understand our present circumstances as framed by legacies from the past, legacies that are never smooth but point us to friction and complexity.

---

All text above by: Katharine Anderson. "Review of Navakas, Michele Currie, Coral Lives: Literature, Labor, and the Making of America." H-Environment, H-Net Reviews. December 2023. Published at: [networks.h-net.org/group/reviews/20017692/anderson-navakas-coral-lives-literature-labor-and-making-america] [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me.]

61 notes

·

View notes