#and has caused so much systemic oppression and created the class system that only widens the wealth gap as time moves on

Text

craaazy that some of you are so determined he stays within the mould when the entire show is chronicling him breaking out of it

#it fills in when he takes the role of crown prince after erik's death#and slowly becomes more rough until it's entirely not in the lines anymore#like season 3's logo#young royals#yr s3 spoilers#spoilers#no one yell at me i'm tagging everything#young royals season 3 spoilers#as someone who has grown up working class w a monarchy that sucks the living daylights out of my country#and has caused so much systemic oppression and created the class system that only widens the wealth gap as time moves on#i'm really exhausted by having to explain that wille being a queer king isn't a progressive thing#and that yah this is a tv show but it presents you an opportunity to#rewire your thinking about real life situations and the actual class system#the people at the top are still oppressive even if they're gay#imperialism is still imperialism even if you let gay people go to war#go read red white and royal blue if you want your gay royal fantasy#this is literally a show about the class system#and how historical systems that are held up by institutions like the monarchy#are a bad thing#and can never be progressive#even if you rainbow wash it

185 notes

·

View notes

Text

Last summer, after the killing of George Floyd ignited protests around the country, Brown got more calls from reporters than she’d received in her entire career. By the time President Biden promised, on his first day in office, to identify and dismantle systemic racism perpetuated by all federal departments, staffers on Capitol Hill were already consulting Brown about the Internal Revenue Service’s impact on racial disparities. “Suddenly people wanted to talk about race and tax,” she says.

With The Whiteness of Wealth, Brown has turned a notoriously boring topic into a surprisingly accessible and lively 288-page book, relying on examples from real families, including her own, to guide readers through the intricacies of a tax code provisioned for just about every milestone in a person’s life—education, marriage, homeownership, childbearing, death and inheritance. Generations of lawmakers have optimized the system for White people, she argues, with the result that in the U.S.’s supposedly progressive and race-neutral tax code, Black people end up paying more than White people with the same incomes.

The challenge for Brown’s research has been all the greater because the IRS doesn’t take race into account when it analyzes its giant trove of tax data. So she had to laboriously stitch together information from dozens of other sources to prove her book’s thesis. The best evidence that the system is unfair to Black people is the sheer size and persistence of the racial wealth gap. The median White family has a net worth eight times the typical Black family’s wealth. According to Federal Reserve figures, that’s the same size gap as in 1983, despite higher incomes, educational gains, and extraordinary progress by individual Black people, including to the highest office in the land.

The book also serves as something of a primer on how wealth works in America, showing how the rich pass assets to their children and why those starting from the bottom face such a difficult climb. Brown devotes her final chapter to advice for Black readers trying to navigate a system that disadvantages them at every turn. “Black Americans need to be defensive players,” she writes, “choosing strategies in their educations, careers, and family lives that compensate for oppressive practices and policies.” She also pushes for major tax changes to erase biases toward Whites and to assist all people, especially Black ones, who are trying to build wealth. Never again should politicians discuss tax reform without considering race, she says. “I literally want to change how America talks about tax policy.”

One afternoon in the early ’90s, Brown pulled out an essay she’d been looking forward to reading by her friend and mentor Jerome Culp, the first professor of color to receive tenure at Duke University’s law school. She’d been feeling isolated at her first academic job, with White colleagues who she says seemed clueless about race, at best. And here was Culp arguing that race should no longer be overlooked in important areas of the law. “There may be an income tax problem that would benefit from being viewed in a Black perspective,” he wrote by way of example, “but until you look, how will anyone know?” Brown called Culp and promised to try.

It took several years for her to publish her first research on the question, focusing on the taxation of married couples. Black Americans are more likely to be single, and if they’re married, it’s more likely both spouses will be working. These considerations wouldn’t have mattered when the income tax made its debut in 1913, because all earners were treated the same regardless of marital status. But in 1930 a rich White shipbuilder named Henry Seaborn persuaded the U.S. Supreme Court to lower his tax bill by imputing half his income to his wife. Congress eventually went along, and ever since, couples with only one high earner have paid less. Brown realized this policy had meant higher tax bills for her parents: The tax code essentially treats a plumber and a nurse who are paying for child care and commuting expenses with after-tax dollars the same or worse than it does a banker earning their combined salaries whose spouse stays home with the kids.

In the next 20 years, Brown went on to systematically catalog other ways in which, when Black families like her own tried to hoist themselves up the economic scale, the U.S. tax system pulled them down. Her colleagues, who were overwhelmingly White, expressed skepticism, however. “Dorothy, everybody knows your work is irrelevant, because Black people are poor and don’t pay taxes,” she says one professor told her, rudely laying bare an assumption she’s confronted countless times. (Four-fifths of Black households don’t fall below the poverty line.)

Brown’s father, James, with her nephew Jamaal in the early ’80s.

Brown’s early published work “caused her lots of professional grief,” recalls her friend Mechele Dickerson, a law professor at the University of Texas at Austin. “People thought you were just trying to be controversial—that you’re just making stuff up.” Those on the left asked if this was about class, not race. Conservatives posed a different question: Wouldn’t these disparities disappear if Black taxpayers just acted more like White ones?

Brown’s answer to both is that your class may change but your race can’t, no matter how differently you behave. “Blacks graduate from college with more debt, do not get jobs as easily as Whites, are not paid the same wages as their equally qualified White peers, are steered toward lower paying jobs, and have an unemployment rate twice that of Whites—yet are more likely to provide financial support for extended family,” she writes in her forthcoming book.

These present-day disparities are piled on top of a shameful history of Black Americans being purposely excluded from landmark federal legislation and programs. “For Whites, there were government interventions that created a middle class,” says New School economics professor Darrick Hamilton, an adviser to Senator Bernie Sanders’s 2020 presidential campaign who considers Brown a mentor. He points to the Homestead Act in the 19th century and much of the New Deal and the GI Bill in the 20th. “When Blacks were able to amass pockets of wealth, it’s been vulnerable to confiscation, theft, and terror,” he adds, citing the devastation wrought in Black neighborhoods by predatory subprime lenders as an example.

Brown argues that “tax policy adds insult to injury” by magnifying the financial toll of Blackness. The tax treatment of housing is a textbook case. Interest paid on mortgages is deductible, but there’s no comparable perk for renters, who are disproportionately Black. Also, White homeowners tend to pocket gains upon resale, which are largely tax-free. In contrast, Black homeowners are very likely to lose money on their investment, because homes don’t usually appreciate much in diverse neighborhoods that are shunned by White buyers. And losses aren’t tax-deductible.

Or consider tax incentives the federal government offers on 401(k)s and other types of retirement savings plans, which add up to more than a quarter trillion dollars per year, according to the Tax Policy Center. Only about half of U.S. workers have a retirement account, and they’re disproportionately White. Meanwhile, Black people are far more likely to have jobs that fail to provide 401(k)s and other corporate benefits, such as health care and flexible spending accounts, that are heavily subsidized by the tax code.

These discrepancies are nothing new—Brown’s father, locked out of the plumbing union for the first 20 years of his career, was employed by a small private company that offered no retirement or health-care plan. Now, though, the gap between different classes of workers might be widening, with the rise of the gig economy and corporations outsourcing more work to contractors. Brown is wary of the trend, seeing it as a “new form of occupational segregation” that’s ensnaring a disproportionate number of Black workers.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The “I” in Christ

Commissioning, Community, and Lessons From Hamilton

(My second sermon, for Confirmation Sunday. You can also listen on Soundcloud.)

This Sunday, a few of us are about to confirm our formal membership in this community of St. Andrew’s; we do this with a profession of faith, along with a promise to seek justice and resist evil. Not only does the process of confirmation ask the question of what it means to be part of a Christian community, but this passage from Luke (10:1-11,16-20) also poses the question of what it means to live out our own discipleship beyond the walls of the church — especially in an age where the image of door-to-door missionaries is something of a bad joke.

Perhaps Christianity’s best-kept secret is this: the actual gospel of Jesus is tremendously relatable to anyone else whose mission is also to seek justice and resist evil. These first disciples were instructed to bear one message: that “the Kingdom of God has come near” — or, to put it in more contemporary language, we might say “another world is possible”.

Jesus says to carry no extra gear, going out like lambs into the midst of wolves; greeting no one on the road, but traveling in pairs. This is a radically vulnerable commission — relying entirely on the generosity of strangers, who may not even care if you live or die — but it is also a commission of interdependence and reliance on one another. Sometimes, we might retreat by ourselves into the metaphorical desert for a while to figure things out. But when we go forth and proclaim the good news of the Kingdom of Heaven, we’re not meant to go it alone. And so, from its earliest moments, Christianity is lived out in relationship.

We also see this in how the very early Christians came together in table fellowship — the root of our communion ritual. Jesus and the disciples had caught on to something that’s borne out by sociological science today (this is why we also had lunch as part of our confirmation classes): deep down, our brain associates “the people with whom you eat” with “family”. This becomes especially resonant when we consider that Jesus’ ministry seems to have been responding, at least in part, to the breakup and dispossession of families caused by Roman encroachment on Jewish ancestral farmlands.

So part of Jesus’ message to these seventy disciples is about going out and finding allies — and through that work, making new and cohesive communities in a time of tremendous social upheaval. Then and now, Christianity creates familial structures that counter the systems of injustice in the world with a message of radical community and genuine connection.

The New Testament, in the original Greek, calls this concept of community or fellowship koinonia, literally participation, partnership, or sharing, with emphasis on the element of relationship; a koinonos, used in the Epistles to describe the disciples’ relationship to Christ and to one another, is a sharer, partner, or companion; a joint participant. So, when we become part of the Body of Christ, we become partners, koinonoi, in acting out God’s intent, “on earth as it is in heaven”. As Jesus says when he is asked when the Kingdom will come (later on in the Gospel of Luke), “the Kingdom of God is among you” (Luke 17:21).

So I suggest that we can look at koinonia — this radical companionship — as a concept that has four pillars. They are economic, interpersonal, internal, and political — and together, they answer a world of imperial domination and hierarchical, transactional relationships with the egalitarian, reciprocal relationships of a truly divine community.

Most of us grew up hearing the Gospel story of how a few loaves and fishes fed five thousand people. When Jesus says “give them something to eat”, the disciples respond with “but how can we possibly go out and buy enough bread for everybody?”. But Jesus had a plan — and we are told that “all ate and were filled” (Luke 9:10-17). This isn’t just a fanciful miracle story; in Jesus’ world, everybody gets enough. This is a total reimagining of our economic model.

We see this principle carried out in the book of Acts, chapter 4: among the growing circle of disciples, it’s said that “there was not a needy person among them”, because people sold their possessions and shared the proceeds; “they laid it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to each as any had need” (Acts 4:32-35).

“But that could never work!” we say, just like in the story of the loaves and fishes. I may not be an economic theorist, but my guess is that what gets in the way is our own self-interest; of course it won’t work if you assume that you and everyone else are just looking out for number one. The missing ingredient here is what the Bible calls lovingkindness, or what I call radical compassion — the key to the interpersonal aspect of the Kingdom of Heaven.

Remember, Jesus’ program is about treating people like family. And what happens when people feel safe enough, trusting enough, to be able to treat each other as a functioning family? “You’re in need? That’s okay, I’ll cover you.” — “Whatever happens, you’re still my sibling in Christ.”

This ideal of the family of God doesn’t end at the steps of the church, by the way. This is what Buddhist teachings mean when they talk about widening the circle of compassion: Talk to your neighbours. Look a panhandler in the eye. Fall in love with the immigrant kids down the corridor who won’t stop bouncing off the walls. Invite that raggedy backpacker down on Spring Garden Road to brunch. But, Jesus cautions, don’t make a big deal out of it; this is just what we do.

But again, we worry, just like the disciples: what if there’s someone in this community who’s really needy, taking up all the available resources and emotional energy? Perhaps that’s where a community can do its best work: helping a person become self-sufficient. Finding them a therapist, even if it means emailing every private practice in [the immediate area]. Finding them meaningful work in the community, something that provides for them and reminds them that their life matters. Granted, that’s extremely hard to do under late capitalism — but maybe that’s a specific challenge for Christians today!

We don’t claim to offer miracle cures here, but we do offer compassion and grace and walking with someone on the road to healing. And if you’ve bought into the Christian message, you’re already imagining the possibility of becoming whole — recognizing the image of God within yourself — and if you know any trauma survivors, you already know that that’s half the battle.

And to support each other like this, we have to be comfortable with being vulnerable. Paradoxically, that’s very hard to do in our white, English, North American church culture!

My childhood pastor used to say that a good church has to be so much more than just “a club for nice people” — part of that is because niceness and civility as we understand them involve building very specific walls around yourself, so that no one sees the mess and the struggle underneath your calm exterior. But when others see that you’re a flawed, messy human too, they respond in kind.

The very best of my church relationships are the very few people to whom I can confess almost anything, and they can confess almost anything to me. We inevitably find ourselves going deep; we have long conversations that are intense and sometimes unsettling, but I always come away feeling more fulfilled, more whole than I was before. And what is salvation in the original Greek but a kind of healing, or “making whole”?

That leads us into the internal work of the Kingdom of God. The hardest lesson we can hope to learn is to give up our preconceived notions of how things ought to be and what others are like. This is where contemplation comes in; it’s about letting go of our hangups so that we can see the bigger picture. This process of self-emptying seems like such a bewildering thought, but it’s a fundamentally liberating process. Just ask our Buddhist neighbours.

So, Christian community calls us to break free from our own self-interest by living as members of one body; as a collective of voices working together in constant dialogue. One might say that there is no “I” in Christ.

And here is where being political comes in. When we live together in lovingkindness, in partnership, when we let go of our attachments to see things as they really are — we begin to see that this is exactly the opposite of what the world wants, both then and now.

We’ve heard [St. Andrew’s lead minister] Russ [Daye] speak of “sin” not so much as an individual moral failing, but as the state of a society propelled by self-interest and operating through systemic inequality, oppression, and violence. And when we see the big picture, we start to see that that’s exactly what’s going on.

A fully realized Christian life, lived out according to the principles of radical community, makes the scales fall from our eyes and highlights the terrible workings of inhumane disconnection and self-interest that our society is based on. That, in the eyes of our world, makes us dangerous.

I recently had an extraordinary online conversation with another queer ministry hopeful, who is not afraid to state point-blank that “love cannot exist [or cannot exist fully] in a space where we are complicit in our neighbours’ suffering and exploitation”. We both agreed that a lot of us moderate Christians aren’t politically active because we can’t truly fathom how deep-rooted these systems of oppression actually are, let alone have any idea of how to stand up to them.

But I invite you to consider that the kind of strong support structure that a fully realized Christian community can provide can be a living “no” to the Caesars of this world, and can empower us to speak our truth to their face, no matter the consequences. “We know love by this,” says the epistle of 1 John, “that he [Jesus] laid down his life for us — and we ought to lay down our lives for one another” (1 John 3:16).

Perhaps, then, there are many “I”s in Christ — together, we are the pillars that hold up God’s kingdom.

However we choose to confront the Caesars of our world, we must always centre our love for God and one another in our actions. This can mean letting our hearts break at the injustice all around us — remember, we are called to be vulnerable! — but it also means means finding and creating opportunities to speak out and stand up for justice; equipping one another with the skills to do so; and lifting each other up in support when those opportunities come.

Let me tell you a story about one such situation.

On June 15, only a few weeks ago, the Pride festival in Hamilton, Ontario was confronted by a group of right-wing agitators carrying giant banners with homophobic messages, shouting slurs, and threatening physical violence. Shamefully, many of these people had the gall to call themselves Christian, using our faith as justification for their hatred and aggression.

Hamilton police, for their part, did very little to protect the Pride marchers.

(By the way, I’ve tried to rely on firsthand accounts of this situation wherever possible.)

What did happen at Hamilton Pride was this: after a similar encounter a few weeks earlier in Dunville, Ontario, where homophobes and counter-demonstrators spent six whole hours trying to drown each other out, an affinity group formed in Hamilton with a new plan. They built a thirty-foot-wide, nine-foot-tall barrier out of black cloth, practiced moving it around as a team — and when the right-wing agitators showed up, the affinity group moved their barrier into position and physically blocked the agitators off from the rest of the festival. They intentionally did not raise their fists to strike at anyone.

But — they still got beat up. As the original members of the affinity group dragged themselves away from the fists and helmets of these right-wing bullies, they looked around to see people they didn’t even know rushing to the scene and keeping the barrier standing. The barrier, incredibly, remained intact until the police arrived a full hour later, escorting the troublemakers out of the park with their hateful signs in tatters.

Community. We lay down our lives for one another.

When asked why the police didn’t get there sooner, an eyewitness reportedly heard the officer respond, “Don’t you remember we weren’t invited to Pride? We’re just going to stand here, not my problem”. [x]

There are, of course, many more layers to this story than I have time to get into here. But the ongoing aftermath of this situation is worth talking about.

The queer community in Hamilton was furious and disappointed, if unsurprised. Remember that there is a decades-long history of criminalization and persecution of queer communities by police, and of police turning a blind eye to homophobic and transphobic violence. That tension doesn’t go away overnight, and it is still very much with us today.

A few days later, a local queer activist named Cedar Hopperton was arrested, purportedly because being present at Hamilton Pride had violated their parole conditions related to a previous act of civil disobedience. (Like me, Cedar goes by the pronouns “they” and “them”.)

But here’s the thing: according to eyewitnesses, Cedar wasn’t part of that incident at Pride. They had stayed at home, where their friends came to them for support and first aid following the confrontation. When Cedar got access to the paperwork associated with their case, it focused almost exclusively on a public speech they had given at City Hall in the wake of the events.

And while they had been heavily critical of how Hamilton police have repeatedly let their community down, they framed their criticism with a prophetic statement:

“...what I am interested in is building community around people who [have] a desire to build a shared idea of the world they actually want to live in. I feel like that’s a higher bar [which] is worth working towards.” [x]

That is what those seventy disciples were sent out to find: The Kingdom of Heaven is near. Another world is possible.

In response to this and what would become at least four other arrests of queer community members, along with frantic attempts to save face by the police and by City Hall, the local activist community decided to go straight to the mayor. In a wonderful example of non-violent protest, some twenty people “dressed in gay masquerade attire” showed up on the mayor’s front lawn early on a Friday morning, and spent fifteen minutes making a ridiculous racket while planting hot pink lawn signs that read “The Mayor Doesn’t Care About Queer People”.

Within an hour, the same mayor who had largely refused to comment on the issue of right-wing agitators harassing and assaulting people at a Pride festival was in the news decrying the lawn sign action as a “violent attack”, and vowing that the perpetrators would be prosecuted to the full extent of the law.

That afternoon, one of the organizers of the lawn sign action found herself cornered by no less than eight police cars. After being brought in for questioning, she was escorted by officers with assault rifles to the central police station, where she was held overnight.

Only one of the right-wing agitators has since been arrested. The mayor, in a stunningly oblivious move, concluded the day by issuing a boilerplate supportive statement about the fiftieth anniversary of the Stonewall Riots.

The organizer who was arrested following the lawn sign action (who has chosen to remain anonymous) had some insightful words that I’d like to share with you. For me, they may as well have been spoken by an apostle in the first century. She said:

“[This is] about us as a community getting stronger — and them being afraid of that. We know [that] because within five hours they mobilized an investigation, manhunt and takedown. We know because they confront us with shaking hands and assault rifles. We know because they [subsequently] responded to a queer dance party with eighty officers on a Friday night. We see it when they make desperate arrests; [like] Cedar for a speech at city hall.” [x]

Because when we start to make a dent in the facade of unjust power, the mask slips, and the true cruelty and desperation of the people at the top gets revealed; just like the crucifixion of Jesus laid bare the horror that the Roman Empire was capable of. And yet, in ways that we do not yet fully understand, we are told that Jesus performed one last radical act of turning the tables; using that humiliating, commonplace death as a jumping-off point into the coldest, darkest reaches of the cosmos, where he sowed the love of God into the very ground of the universe.

Our anonymous lawn sign activist continues:

“In that, we can also acknowledge something else; we are winning. They are afraid of us and what we can do. They are embarrassed. They are losing ground.”

This takes us right back to Holy Week — when the authorities start planning Jesus’ arrest in the wake of the non-violent protest march that we remember as Palm Sunday, because they’re afraid he’ll incite the people to rebellion. When we start to successfully seek justice and resist evil, the powers that be, propelled by self-interest and sustained by systems of cruel inequality, are terrified.

She concludes with this wonderful statement of commission — and I’d like to think it can be our commission too:

“So let’s keep this up. Let’s keep getting into ... public spaces. … Challenging the things that harm us — even when they are institutional and systemic. … Let’s build towards the world we want to see – and share and learn those skills together. … Not just every four years — [I would add, not just every Sunday] — but every single day”.

Amen.

July 7, 2019 (Confirmation Sunday) — St. Andrew’s United Church, Halifax

Selected further reading:

Center for Action and Contemplation, “Consumed with Love”

Queer Theology podcast, “A Community of Care”

Rethinking Religion, “Buddhists Don’t Have to Be Nice: Avoiding Idiot Compassion”

#tamsin writes#tamsin sermonizes#queer christianity#queer theology#anti-oppressive christianity#Reclaiming Christianity#rethinking theology#united church of canada#uccan#faithfully lgbt#long post

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

America: A Prophecy

‘What God is he writes laws of peace, and clothes him in a tempest?

What pitying Angel lusts for tears, and fans himself with sighs?

What crawling villain preaches abstinence and wraps himself

In fat of lambs? No more I follow, no more obedience pay!’

So cried he, rending off his robe and throwing down his sceptre

In sight of Albion’s Guardian; and all the Thirteen Angels

Rent off their robes to the hungry wind, and threw their golden sceptres

Down on the land of America.

- William Blake, 1793

America is becoming ungovernable.

It’s simply much too large, too varied, and much too polarized for any one candidate to garner even the plurality of support needed to effectively govern as a president, complicated by the weaknesses of America’s social/political system that demands a democratically-elected executive somehow stand for the nation as a whole.

This isn’t a ‘diversity’ problem or a call for ethnic of cultural homogeneity. I’m from a country with greater diversity than the United States and we manage just fine. (I mean we’re facing a rising tide of rightwing resurgence exacerbated by decades of failure by ruling parties to replace the antiquated first-past-the-post voting system so I wouldn’t call us “fine” but those issues are rooted in numerous social trends, not racial demographics.)

It’s more a condition of the scale of Unites States and the internecine conflicts of groups within it. I remember during the last election hearing a lot about letting perfect be the enemy of good: ‘yes this candidate might not understand your ethnic/social/cultural group particularly well or speak to your issues, but you ought to vote for them anyways.’ From a certain point of view that’s true - I think it hardly uncontroversial to say that the world generally and America specifically is demonstrably worse under Donald Trump than it would have been under Hillary Clinton.

But leaving aside the candidates as individuals for a moment and viewing them purely as symbols the President-As-Unifier and the electoral circus around it becomes faintly absurd. The more often you have say to one group or another ‘stop needing a candidate to be exactly like you and just give them your vote because they’re more like you than the other guy,’ the more you overlook centuries of pain and marginalization. Groups that never had voices before have voices now: loud voices, prominent voices, and they are finding that they don’t want to sit down and shut up in the interest of some mythical unity anymore. They can’t. And therefore these presidential primaries are only going to get worse as things go on. They’re already getting acrimonious again, and those groups who have been told to swallow their voices again and again if they don’t want things to get worse are realizing that they’ve been used as tools as the status quo for far too long. Things don’t get worse when they shut up and vote like they’re told - but they never get better, either. Not in meaningful ways, or not rapidly enough to be meaningful to most of them .(‘By supporting the status quo you achieved a social victory and it only took you 45 years and your entire youth to see it come to fruition.’)

The ‘baby-steps’ of change have started to seem less like care and caution and more like infantilization.

When the only people who could vote in America were white, adult, male property-owners you could have two political parties: there really was more that united voters then divided them, such as all voters belonging to the same class, ethnicity, language group, social background, Enlightenment-moulding education praxis, and willingness to compromise on treating human beings as disposable tools for labour. The greater the franchise has expanded in America the farther and further from that ‘unity’ things have gotten.

Since the Trump election in particular the question is asked: “What’s caused the polarization of America?” The real answers are a multitude of factors: unhealed wounds in the body politic after the Second Indochina War; the malaise, complacency, and self-indulgent omphaloskepsis of being the so-called superpower in the 90s; post-colonialism and free market economics bringing the worst ravages of capitalism stateside and decimating the illusion of a stable middle class. There’s lot of reasons as things are rarely simple.

Perhaps the most critical cause, however, the one with the greatest impact, has been this widening of not just the franchise but the gradual realization by the newly-enfranchised that they vocalize social discontent and express it - or at least attempt to express it - through voting. The ‘silent majority’ can only exist when the majority of oppressed and marginalized groups suffer in silence. The divisions that exist now existed in the 1950s, but they are only now being vocalized in such a prominent way. Even the labour movement and the Great Depression in the thirties did not sufficiently create an impression of intractable internecine rivalries such as now can be seen dividing America.

Republicans have understood this for a long time. This is why their politics have grown more and more tribalistic as the years have gone on. So long as they can dominate amongst specific strata of demographics they don’t have to care about winning any kind of nation-wide majority. They can fixate on the plurality that rigidly shares its belief systems: a rigidity created by and continually reenforced by the rhetoric of Republican doctrine and dogma. Democrats coasted on this for years, thinking that if Republicans focused only on a handful of groups then they benefited simply by having everyone else by default.

But it didn’t really work out that way. Gerrymandering by Republican bureaucrats helped a lot here by segmenting voting districts so that anyone outside the Republican voting base got split across multiple voting districts and never coalesced into more than a handful of centralized sources of power that the Democrats could rely on, but there’s a bigger issue. This Republican plurality positioning has only short-term value: they’re a demographic time bomb and as far back as 2012 I can remember their saner members talking about this as a matter of some urgency. But they were ignored, and the GOP is on a death-cult rocket ride to eventual obsolescence, although they’ll pull as much of American down around them as they go in an act of spite.

But that’s not the problem (or, rather, it is a problem but it’s not what I’ve come here to talk about today). Democrats got so used to coasting on being the party of the default that they lack any ability to talk to groups specifically. Nobody likes being taken for granted and they’ve started pushing back. Clinton’s failure to secure a margin of victory overwhelming enough to overcome the limiters of the Electoral College showed that two years ago: plenty of groups stayed home, an act of protest against a party that expected their vote for no other reason than 'not being the other guy.’

Nobody seems to have learned that lesson very well. Imagine two, three presidential elections from now, when the GOP is a spent force whose membership lists are now covered with dead people. (The oldest baby boomers are over 70, and when age brackets start to die in numbers it becomes a cascade. I can remember going from parades of WWII vets to a handful of wheelchair veterans in about a decade, and from some WWI vets to none in the same length of time.) For the younger among you two, three elections might seem like a long time, but it isn’t: years rush by faster than you think. So picture that world with a GOP in terminal decline and a Democratic party witnessing the prophesied triumph of demographic inevitability.

That’s essentially a one-party state, but a party that already struggles to be enough things to enough people now is going to buckle under pressures the American political system simply wasn’t built to handle. America was built around being a two-party state - of being a country in which the majority of people fit comfortably enough into two broad binaries and vote accordingly.

But they don’t, and they can’t, and America as it presently exists may be quite literally ungovernable. The centuries of appalling violence within America only complicate the picture further - it’s the sort of mixture of history, population, and anger that lead to the Balkan Wars, the conflicts between former members of the Warsaw Pact, and more recently the creation of South Sudan. America already had one civil war, there’s no reason to think that a re-fragmenting of America isn’t possible, especially given how contentious the language seems to be among different groups.

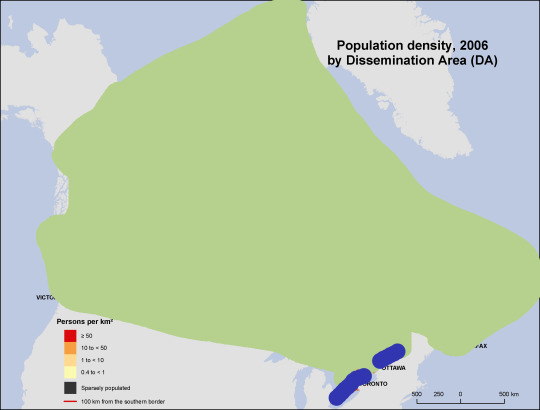

America has a scale problem, and I think Americans don’t really understand this. I live in the second largest country in the world by area but nobody actually lives here. See this?

It’s about fifteen years out of date, but the population hasn’t expanded beyond those yellow borders: just make the red bits much redder and you’re golden. Yet even this is still not getting the full picture. Let me show you with my photoshop skills:

Everybody in the green bit:

Does not equal the population of the blue bit.

If Canadian politics ran purely off of direct voting the entire country would be dominated by a group of people who live in about 0.14% of the country.

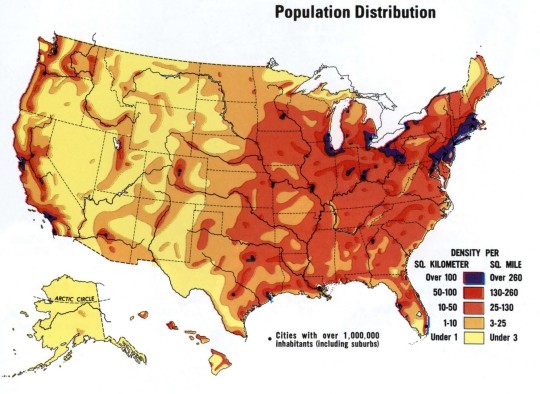

What this means in practice is that for all that Canada has different grouping of cultural diversity (i.e. the political/social/cultural makeup of PEI as distinct from Vancouver as distinct from Iqaluit), should a civil war of either literal or abstract nature break-out the power of bodies is still located in one place. This is the population density of America:

Look at all those different concentrations of people and power.

Like I said Canada does, of course, have other centres of power outside of old Upper/Lower Canada: despite what it thinks Toronto is not the entirety of the universe. But the multiplicity of metropolitan spaces and concentrated population centres such as you have in America don’t exist here.

What am I getting at with this? America has spaces of intensely regional identity on an enormous scale. In Canada, for example, even Quebec separatism seems to be dying a slow and painful death. We’ve all got our our local identities, but Canadians are still mostly Canadian first, something else second. America by contrast, have fought a bloody civil war over slavery that afterwards was reshaped (falsely) into a war about regionalism, which mutated later into tribalism. This is why right-wingers in Union states spout Confederate flags. The flag doesn’t represent the literal loyalties of the Confederacy but its values: racism, white power, using human being as disposable tools for personal enrichment, and racism. (Anyone wanting to argue is welcome to read the Constitution of the Confederacy, which is nothing but the US Constitution with extra bits about slavery and river trade stuck in: it’s not subtle, and the character of the Confederacy is not up for debate.)

Americans - or at least a worrying percentage of Americans - tend to link their national and tribal identities quite strongly: all you have to do is watch a Trump rally to work that out. To be an American is to be like me - thus, anyone unlike me is unAmerican. That is the sickness, the rot that is chewing up America from the inside. The right wing seized hold of the idea that the only Real Americans are those just like them, and other groups have started to adopt the same mindset out of self-defence, and these fractures are only going to deepen. Take that and add to it the way that political tribalism is fusing with regional identity and you begin to see the scope of the problem: you’re reaching the point where nobody from Region A can ever be thought of having any authority over Region B because Region A people are the Other. (Trump will probably be the last New Yorker City dweller to ever hold sway in the GOP: his successors will bind themselves to the base not merely through the tribal shibboleths of hating brown people and the poor who believe in improving their lot through anything other than force of will, but also through regional identity. No Californian Republican is likely to ever see front-billing again: you’ll prove your loyalty by only living in the ‘right’ places - solidly red, with no compromising purple of ideological weakness.)

So look at the Democratic party two, three elections from now: the party of everyone in the country who isn’t the GOP. How is that a functioning political group? What could it stand for that would effectively cover such a diverse collection of people? You cannot be the party of the centrists and the progressives and the leftists and the disaffected rightists and the communists and the socialists and the ethical capitalists and the neo-Marxists and the socially-liberal libertarians and the left-leaning rich and the remaining middle class and the working class and the vested corporate interests unwilling to directly support fascism and on and on and on. Democrats can run on the ‘Not Trump’ platform for the moment because the GOP will likely be the party of Trumpism from here on out. (The GOP had enough sense of self preservation to distance itself from Nixon back in the day, but ever since it refused to repudiate Reagan after Iran-Contra it’s shown that it is only ever going to double-down on its bets from here on out: it’ll be riding this train until the very bitter end.) But ‘not Trump’ is barely sufficient even now - because people want to know what the party is for, not just what it’s against. And it can’t be for everything but Trumpism - it’s too broad a field.

So America is rapidly become ungovernable, because one party wants to serve a demographic facing extinction, and the other wants to be the Big Tent of literally everyone else no matter how different they may be. Which looks great on a poster about tolerance that you’d hang in a kindergarten class but is untenable when trying to unify 18-year old queer anarcho-syndicists of colour and 50-year old suburban capitalism-apologist whites: their goals are too divergent for harmony to make political sense. (And yes, ‘suburban’ is an antonym of ‘queer.’ Trust me on this.) They want fundamentally different things; just because they mutually do not also want a third thing does not mean they make stable, good, or even plausible allies. The Waffle Guardians and The Crepe Defenders can come together and agree that Pancakes are garbage but that is the end of their common cause, not the start of meaningful co-operation on a variety of issues mattering to both groups, because those don’t really exist.

So America is becoming literally ungovernable because its institutions are incapable of operating outside of a narrow binary between two relatively close points. It was not designed, and cannot handle, the intense tribalism of the moment, nor the future that will contain a multitude of independently-minded political groups who are no longer willing to engage with big tent politics that ultimately never forward their own causes. We talk right now about a battle for the ‘soul’ of the Democratic party, but that’s bull. The fight is for who gets to keep the branding and the cachet of the name ‘Democratic Party’ - the next step is party secession, first when the centrists realize the progressives really do mean to literally destroy them and the status quo they hold dear, and then further fragmentation from there.

I could go on and on down various laneways here about how increasing tribalism is straining the American system on a structural level. Take the Supreme Court, which only functions without a heavily politicized judiciary because otherwise democratic desires are stifled by entrenched judicial positions that judge issues only on their political merits. Or take how binary elected government in general only works with the understanding that every time power swaps between two groups the next group doesn’t instantly undo everything the last group did out of spite. (We’re seeing that in Ontario right now, actually, as a serious of ‘fortunate’ events brought into power a man so craven he makes Donald Trump seem downright generous in comparison. Our new premiere realized that if he just stops caring about re-election he can do whatever he wants to enrich his corporate buddies in the short-term, so he’s doing things that are enraging even his base, like removing anaesthetic coverage from colonoscopies. He, like Trump, is a ‘political outsider’ but unlike Trump his ego doesn’t need people telling him they love him - he’s perfectly happy being a vindictive thug, so even though he used populist anger to get into power he feels no reason to do anything for anyone who put him there. This is what happens when you elect a suburban drug dealer whose only goal is to revenge himself on an entire province for not taking his brother the crack-smoking mayor seriously. Ontario is so, so screwed.)

Fundamentally, presidential republics are a disease. The American republican system has damaged every country its ever been exported to as its central structural weakness - an ability to be easily subsumed by autocrats - has been taken advantage of in basically every case, not to mention its tendency to fall into political deadlock. America’s own legal experts don’t recommend the country’s constitution to other - RBGs herself said that she would not use the US Constitution as a model to any country creating one today. The fractures that so ruined South America and the emerging African states that took the Us as their role model are finally happening in American itself. This feeling of paralyzation will only worsen in the years to come: it was practically baked-in to the political system from the start, the inevitable breaking point of planned obsolescence.

America must either change - such as adopting a parliamentary model better-suited to handle the diverse social, ethnic, cultural, and regional demographics of such a large country, or taking an axe to existing institutional binaries and demolishing the two-party state - or die. I recognize the irony in saying that there is a binary choice about handling the inability to handle non-binaries, but there is a third option: sticking with the status quo. A status quo that is groaning under the strain of modern America, a status quo for which simple, minor modifications are unlikely to be enough to relieve the pressures the system is under. You could try that. You’ve been trying it for decades. How’s that choice working out?

Two to three elections from now the idea that you can neatly divide political extremes into Liberal and Conservative, and that harmony can only be found in collaboration, will be so dead that not even the most committed advocate of the status quo will be able to ignore the smell - though he will, of course, say that the onus is on other people to come back from their ‘extremist’ positions, because it’s never centrism’s fault when people reject it as insufficient to the crises of the present.

To the Americans who read this, you’re going to have to choose - and it really is a choice, surprising as that may seem. You can choose to let America end. To let it die. Countries die all the time. That wouldn’t necessarily be a bad thing. Say you’re from a blue state: do you still want a future of sharing a country with a red state? America stays together because ‘more unites us than divides us’ - but is there a point where that truism can no longer be consider true? And at that point is there still value in remaining a union? Meaningful value, and not just a sense of duty or obligation to an ideal that doesn’t seem to have any real-world resonance? What is the point at which political compromise becomes something you can no longer stomach - when working together goes from making deals with the opposition to making deals with the devil? When do hyperbolic statements like the other side being 'the devil’ stop sounding like hyperbole? For all that I talked about the Founding Fathers and their immediate voting heirs being ‘the same’ one point on which they disagreed was slavery - but they found themselves able to compromise on the use of humans-as-property for labour. That I one of the founding pacts of America: some of us don’t like slavery, but we can live with it in the interest of unity. Could you, a time-traveler-turned-Founding-Father, make the same choice? On what are you willing to compromise to keep the union a union - what agreements could you make and still be able to meet your own gaze in a mirror?

Keep in mind that choosing ‘change’ is no guarantee that the change will be successful, or that the post-America that emerges from that change will be any more a place you want to live in than if you had chosen to keep America alive. I merely want the full and total weight of those decisions to be clear. American compromised on slavery at the moment of its birth: it has lived with the consequences of that compromise ever since. America continues to exist because matters were compromised on - some benign, some heinous, all done in the interest of a greater good. Are you willing to make such compromises future - and are you willing to accept the consequences of what might happen if you are not?

There is no ‘going back.’ The post-Trump America will not be a ‘return to normal.’ It can’t. Too many lines have been crossed for there to be a simple return to ‘normality’ when all this is done: that normal is dead. If you choose to try and reinstate it - if you choose neither change nor death but the old status quo - then the problems that birthed this current crisis will remain. Is that status quo strong enough to withstand a second round with such events?

That’s something you’ll have to decided.

Until then, American will remain ungovernable.

#america#United States#united states of america#canada#dominion of canada#william blake#america: a prophecy#democrats#republicans#GOP#donald trump#hillary clinton#doug ford#ontario#The South#The Confederacy#(of dunces)#(racist dunces)#(garbage shit people who were racists)#long post#politics#trumpism#fascism#usa#demographics#diversity#social change

1 note

·

View note

Text

Gun Control Lead Off

As a Marxist, I cannot and do not support gun control reforms. American violence did not begin with school shootings, nor will it end with regulating individual weapons. It's important to point out that school shootings are extremely rare, with statistics showing children are more likely to die on their way to school any given day than being shot inside of their school. Though a difficult topic to navigate emotionally, we should not let the media magnifying glass dictate how we approach the issue of violence in our society. With ever-increasing instances of police brutality, imperialist attacks on the working class abroad, deathly poverty and inequality, amongst countless other things, it's understandable to see America as becoming increasingly violent and needing a fix. Sadly, no quick fix exist. Any attempt to address violence in our society must also be paired with an analysis of the root causes of violence, how the State perpetuates and uses violence politically, and how careless reforms will mean increased violence in our most oppressed communities.

Historically, gun control has been used against black/brown people and the working class to uphold white supremacy and the violent capitalist mode of production. This can, and should, be traced back to the conception of our country as a colony and then as a State. The United States was founded on violence, against both indigenous populations native to the lands, and towards the enslaved Black and brown populations who were made to literally build our country. The Second Amendment is a product of this time; the settlers were legally able to continue to use violent means to expand the colony state by waging war against the Natives they found to be in their way. Ridding the Constitution of the Second Amendment will not rid the Constitution, nor the country, of it's violence or hypocrisy. Tidying up the Second Amendment will have grave consequences. You can't erase history or simply smooth over centuries of racism, sexism, and class conflict. Especially not with gun control laws from the same institutions creating and upholding those oppressions. From slavery and colonization, to the Trail of Tears and the black codes, our “justice system” was crafted to uphold this violence for the continuation of capitalism. Mumia Abu-Jamal put it's it eloquently,

“Social structures—courts, police, prisons, etc.—have within them a deep bias about what constitutes crime and what does not. Any social structure is a product of its previous historical, economic and social iterations, and these previous forms bear significant influence on later forms. The present system, in addition to being increasingly repressive, is the logical inheritance of its racist, hierarchical, exploitative past, and it is also a reactive formation against attempts to transform, democratize, and socialize it.”

When attempting to address violence, we cannot take reforms out of the context of the violent State in which laws and reforms are written and enforced. Any guesswork of demands will have very serious real-world consequences, especially in our communities of color and working class areas. These communities already bear the brunt of capitalist violence, with disproportional rates of poverty, homelessness, unemployment, drug and alcohol abuse, and over-policing, to name a select few. Gun control laws will be a double-edged sword in increasing violence by ramping up racist enforcement of superfluous laws, and by leaving those who most need protection personally defenseless while under more policing. Once we acknowledge who the state prefers policed and defenseless, it's only logical to assume our government will act as it always has in the face of any “violence” related reform.

As socialists we understand that our society has enough homes, work, food, medicine, etc., to go around but supplies are increasingly monopolized in limited hands. Upholding this system of capitalism requires violence, from the police who enforce fundamentally unjust laws, the capitalists who enforce wage labor for survival, to the military who plunder the working classes in other countries when sectors our country has been squeezed to its pulp. If this is hard to conceptualize, imagine being homeless and sleeping underneath the window of an empty townhouse. What stops you from breaking inside to get a good, warm nights sleep? The property laws that enforce homelessness, the militarized police that enforce those laws, or the threat of violent prisons where lawbreakers are enslaved? We must ask ourselves, where is the violence in this situation rooted? Is it when the homeless person breaks a window, or when the police break the homeless person, or is it the fact that a home sits empty while members of our community freeze in the streets. This is a violence that effects every person that lives under capitalism and imperialism, as we all must participate in the system for survival. To address the violence we must address the system.

By acknowledging the root cause of our historical and overarching violence problem, we can analyze which reforms help the working class, and which do not address the root and in turn harm the working class. For example, the liberal reform of increasing the number of “school resource officers”. While on the surface this may seem helpful in the specific instance of fending off a school shooter, these officers essentially take on the role of school police throughout the school year when school shootings aren't happening. Armed guards, metal detectors, strict discipline, constant surveillance... These reforms manage to widen the school-to-prison pipeline by simply removing the pipeline. It has incalculable consequences for every black and brown student who are already 4 times as likely to be suspended, twice as likely to be arrested, and nearly twice as likely to be expelled than their white counterparts. This idea of reducing violence in a single theoretical scenario will definitely increase the violence our marginalized students face every single day. The resources could be better spent by hiring new teachers, ensuring classrooms have enough supplies, or expanding extracurricular activities. To quote Angela Davis,

“When children attend schools that place a greater value on discipline and security than on knowledge and intellectual development, they are attending prep schools for prison."

Another liberal reform worth mentioning is the idea that stricter background checks will curve gun violence. Currently through the Brady Bill, firearm retailers must run a background check on purchasers through the National Instant Criminal Background Check System, an FBI database that enforces the Gun Control Act of 1968. The word “criminal” should immediately alert anybody who understands the mechanisms of the State. To quote Mumia once again, “crime is simply a conception of harm held by those who have power to make laws.” Under the Gun Control Act, people prohibited from owning guns include anybody arrested of a crime facing over a year imprisonment, anybody taking illegal substances or medical marijuana, any immigrant that lives in the US illegally, and anybody tried for domestic violence. Granted some these sound reasonable enough, if it weren't for our racialized and inherently violent state upholding these controls. Black people are incarcerated at a rate of 3.6 times that of white people, and poorer people are more likely to be incarcerated than those of a higher class, meaning the “year in jail” limit disproportionately limits the working class, specifically working class black people, from owning arms. The undocumented community is also barred from legally owning arms, despite the constant threat of violence and deportation from ICE. While those convicted of domestic violence are barred, this does not include law enforcement, who's families are 4 times more likely to experience domestic violence than those of the general population. To allow the State to tighten background check criteria will only perpetuate the racialized enforcement of who can and cannot own arms. Men like Stephen Paddock, the Las Vegas shooter who murdered 58 people and injured over 500, routinely pass the background check as it was not crafted to stop them. How could a law be written that restricts certain types of people, frankly white males, usually with a history of DV, militarism, or right-wing ideologies, from owning guns when so many of those same types of people make up our police forces, militaries, and governing bodies?

All of these examples are way the State prohibits people from legally owning guns, but we must not forget that legally obtaining arms is not the only way to obtain arms. Our country has an estimated 300 million firearms, not including black market guns for which we don't have an accurate count. If a person wants to buy a gun legally, they're subjected to State scrutiny that discriminates based on race and class. If a person wants to get a gun illegally, or off the books of the racist State, they risk much higher charges and longer incarceration if caught. Given the States lack of interest in regulating arms manufacturers, who “donate” to the NRA who then buy the politicians who run the State, guns themselves do not seem to be the problem. Rather, it's when the State's monopoly on violence is threatened by those who have the desire or material benefit in addressing the State itself. Gun control laws, and the police who enforce them, are simply self-preservation acts of racist, oppressive institutions.

While this all may seem discouraging or abysmal, analyzing the root causes of violence and the politics surrounding violence is vital to eliminating it. Capitalism and our bourgeois government that upholds it was founded on violence and must inflict violence on the working class to keep itself running. Attempts to address violence without addressing the root cause will fall short, will not bring about a radical change, and can possibly backfire by placing the working class under tighter State scrutiny. If we attempt to change the system within it, our choices are largely between the Democratic and Republican parties. While the Republican party is quickly written off for its strong ties with the NRA, violent militarism, or general disregard for human life over profits, it's worth noting that the same can pretty much be said for the Democratic party as well. They're the "lesser evil” choice between the two, but once we adopt the realization that capitalism is the root cause of what we believe is so bad about the Republicans, we must also realize that the Democratic party is a capitalist party that overall exists to uphold capitalism and is extremely violent as well. For example, the most unarguably “progressive” of the Democrats, Bernie Sanders, supports the state of Israel in its colonization of Palestine, a mirror image of the colonization the white settlers perpetrated on the indigenous here in our own country. Are we willing to ignore violence as long as it's not us, not our country, not our people? Or do we stand in solidarity with the working class around the world in the rejection of violence, be it colonialism, capitalism, imperialism, etc. Democrat Barack Obama deployed drone strikes 10 times as much as his predecessor George W Bush. He spent billions of taxpayer dollars to bail out the failing big banks, while income inequality, homelessness, poverty, and wage stagnation continued to grow. He also built the deportation apparatus, the Department of Homeland Security, that Trump utilizes to deport people today. If I didn't say “Barack Obama,” you probably would have guessed he was of the Republican Party. And if so, it's due time to break with the idea that the Democrats are the “lesser of two evils” when even the “lesser evil” includes deportation, drone strikes, imperial wars, and general negligence to improving conditions of human life.

It's becoming increasingly obvious that we must move away from the two-party, capitalist system and build towards something that prioritizes human life over greed, profit, and violence. Violence cannot be reformed away in an inherently violent system. As a matter of harm reduction for the time being, we must support any reform that challenges the capitalist hold on the working class is a reform that will in turn reduce violence. We need to demand higher wages and an end to austerity, to address income inequality that forces people into poverty while the wealthy exploit and squander. We need to demand guaranteed free housing to eradicate homelessness, as housing is a human right. We need to demand a socialized, single-payer healthcare system, as healthcare is a human right as well. “Demand” does not mean begging the capitalist class to piss pity upon us, but it is a declaration that we will stop at nothing to bring about our demands and the end of capitalism and its ills. It's inevitable that more people realize the violence capitalism perpetrates worldwide, and that is it in the material interest of society to eradicate capitalism by building socialism. We don't need racism, we don't need sexism, we don't need poverty or homelessness, we don't need wars, and we don't need to slave away our lives creating profit for the wealthy. This is in the interest of all of humanity. As Karl Marx once said, “Capitalism contains within it the seeds of its own destruction.”

6 notes

·

View notes