#chicago herpetological society

Text

July CHS Junior Herpers Meeting: Celebrate Frogs!

Hop on over to the July Junior Herpers meeting! This month we're celebrating frogs! Kids will be able to make a fun frog craft, play some frog-themed games (and win some froggy prizes!), and learn about frogs together. As always, everyone is invited and the meeting is free to attend. It will be held from 1-2 PM CST on July 16 at the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum.

Families are welcome to stay for the main CHS meeting, too- even if you're not a member, this is a great meeting you don't want to miss!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reason number one you should attend Chicago Herpetological Society meetings: Nakajima WILL sit on your shoulders or lap or chest and WILL make it known how much fun she thinks people are. Also she might tell your kids secrets.

I still can't believe how amazing she is with kids. This is not a domesticated animal! This isn't a dog with a drive to work with people! This is a lizard who simply loves human interaction, and I am so grateful she ended up with me. I miss Kaiju every day but she makes the absence tolerable, and I'm so glad she and I have an avenue through CHS to share her with the world.

443 notes

·

View notes

Photo

You know the Russian matryoshka dolls? Well, while CT scanning a Samar cobra snake from our collections, we found another snake inside: a rare species of about the same size!

You don’t have to undertake expeditions to discover new things. While micro-CT scanning a Naja samarensis from the RBINS collections, our biologist Jonathan Brecko saw not one, but two snakes appear on his screen! The highly venomous Samar cobra from the Philippines, about 35 cm long, had eaten another snake of about the same size before it was collected in 1998.

Brecko and Olivier Pauwels, conservator of our recent vertebrates collections, decided to dissect this Naja samarensis specimen and found in its stomach an adult female Cyclocorus nuchalis nuchalis, whose head and nape had been digested. Cyclocorus nuchalis nuchalis is a poorly known forest-dwelling terrestrial snake, also endemic to the Philippines (with a distribution limited to Basilan and western Mindanao islands).

Until now, we knew the diet spectrum of Naja samarensis was made of amphibians, reptiles and rodents. We can now add the rare snake Cyclocorus nuchalis nuchalis to the list. The story of the snake within the snake is published in Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society.

#snakes#cobra#philippines#natural sciences#naturalsciencesbrussels#collections#ct scan#digitalization#Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences#nature is the greatest show

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

2020 Collection Goals

New year, new goals for my collection. I’ve been planning on slowing down my collecting habits this year for a variety of reasons, although a big one I keep coming back to is that I want to be much more deliberate with what I collect. I’ve struggled with collectors guilt for some time but it became more obvious the later half of last year (and I plan on making a post detailing it more). I don’t plan on stopping collecting altogether, although I only plan on getting specimens I really want. And I have to have a good reason for wanting it besides “it’s cool”. So here are my three big goals.

Round out my collection of musteloids. I have a complete set of US mustelids that I can reasonably own (two species aren’t legal to own without permits, one is extinct and remains are very scarce) but I’d like to include more mustelids from around the world. At the moment my only non-N. American species is a European badger. The superfamily Musteloidea also includes Mephitidae (skunks and stink badgers), Procyonidae (raccoons and relatives), and Ailuridae (red pandas). In 2020 I’d like to get a complete collection of US skunk species, I currently have two species and there are five total species found in the United States. There are two other species of Procyonid found in the US besides common raccoons but these appear to be rarer than the skunks.

Grow my primatology reference collection. I’ve made mention to the fact that I have a background in anthropology on here, it was my minor in college and I’ve taken courses in it at the University of Tennessee as a visiting student. Primatology is actually a sub-discipline of biological anthropology, and given that I plan on pursuing a career in biological anthropology having a collection I can easily reference could be beneficial for me. My old college is also potentially interested in me bringing in my primatomorph collection (primates and their closest relatives, colugos) for their primatology labs.

Include more complementary skulls for educational talks or demos. A big personal goal I have for 2020 is to do more educational talks and events. I’ve participated in educational events with the Chicago Herpetological Society so far and I might be able to do talks at schools with my skulls. I want to focus on related species, convergent evolution, and divergent evolution. This sort of stuff always interested me in school. Additionally, doing more talks opens up the possibility of me applying for a few permits that would let me focus on a few more family or genus focused collections. Permits might also become necessary for me in the future, for reasons I’ll go into at a later time.

What are goals other people have for 2020?

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Alligators make terrible pets: 'You're basically dealing with a dinosaur.'

New Mexico officials seized this seven-foot American alligator (seen here at his new home, the ABQ BioPark Zoo) from a private home, where he'd been kept illegally for a decade.

A rise in the abandoned reptiles around the United States—including two recently found in a Kansas creek—has raised concern among experts.

JULY 31, 2020

Something unusual was lurking in Wildcat Creek, in Manhattan, Kansas, a small college town on the prairie. In June, townsfolk spotted two American alligators swimming in a body of water better known for reptiles such as garter snakes and painted turtles.

Further investigation revealed that a thief—still at large—had stolen the gators from a local pet shop and released them into the creek. Rescuers set humane traps to catch the animals, but the female, Pebbles, died after falling into the water inside one of these traps. The male, Beauregard, eluded capture until late July, when a construction worker caught and returned him to his owners at Manhattan Reptile World, according to their Facebook page.

The two gators, kept at Manhattan Reptile World under a state zoo permit, had previously been illegal pets, living in a pool and a bathtub in Manhattan and Kansas City, according to a news release. (Learn more about why people want exotic pets.)

The incident—particularly the female’s untimely death—highlights the often problematic, yet not widely known, phenomenon of keeping pet American alligators, which are native to the U.S. Southeast, experts say. (Read more about the exotic pet trade.)

Formerly endangered, American alligators reached their nadir in the 1950s because of overhunting and habitat loss, but conservation efforts returned the species to healthy numbers by the mid-1980s. Weighing up to a thousand pounds, these behemoths live in wetlands, rivers, lakes, and swamps, feeding primarily on fish, turtles, snakes, and small mammals. (Watch alligators on the hunt.)

Official numbers on how many American alligators are kept as pets don’t exist, but some states have estimates. There are likely 5,000 in Michigan; at least 50 in Phoenix, Arizona; and as many as 52 of the prehistoric reptiles are surrendered to the city of Chicago each year.

American Alligator, Alligator mississippiensis

TYPE: Reptile

DIET: Carnivore

GROUP NAME: Congregation

AVERAGE LIFE SPAN IN THE WILD: 35-50 years

SIZE: 10-15 feet

WEIGHT: 1,000#

In recent years, wildlife officials across the nation have noticed an uptick in alligators abandoned in parks, creeks, and other public places. In 2019, six pet alligators went on the loose in Detroit (one was shot to death), and in August, the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish seized an alligator from a Santa Fe man who had kept the animal illegally for 10 years.

Gator laws

Ownership laws for alligators vary by state and municipality. While keeping them is legal in Michigan, parts of Detroit ban private ownership. In other states, such as New Mexico, pet gators are illegal without a permit, and in Arizona and New York, private ownership is banned.

Such regulations don’t faze many collectors who covet palm-size baby gators. A quick search for pet alligators turns up dozens of websites that sell juvenile alligators for anywhere from $150 to $15,000 (for an albino animal). Most of these young reptiles come from legal alligator breeders in the Southeast who sell the animals wholesale to vendors.

The black market trade of these animals has long been “a big problem,” according to Matt Eschenbrenner, director of animal care and conservation at the Great Plains Zoo and Delbridge Museum of Natural History, in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. It’s likely that most of these animals originate in Florida, says Russ Johnson, president of the Phoenix Herpetological Society.

Florida has strict alligator farming laws and inspection protocols, but not all breeders play by the rules. In 2018, the state reported 21 active alligator farms that produced legal hides and meat. Not present on this list are unlicensed operations that illegally breed gators as pets. (Read about the largest seizure to date of illegally caught reptiles.)

Bone breakers

Most gator pet owners are unprepared to care for an adult animal that can reach 14 feet and live 80 years, Johnson says. When that cute baby gets bigger and less manageable, the owner faces a real conundrum. “It’s not like owning a cat or dog that will return love,” he adds. “You’re basically dealing with a dinosaur.”

To capture their prey, alligators are armed with strong jaws lined with up to 80 teeth. If captive gators don’t get enough food—a common problem—they can get cranky and bite, easily breaking through human bone. “It’s not the alligator’s fault,” Johnson says. “The alligator was just being an alligator.”

This happens, he says, because feeding an alligator is expensive. Adults need nourishment such as whole chickens or pork with the bone, and Johnson says he pays about $150 a month to feed each adult alligator at his rescue facility.

Alligators also need a large pool of water to thrive. Bathtubs and kiddie pools, preferred by many pet owners, aren’t good enough, Eschenbrenner says. Buoyancy relieves the weight of an alligator’s internal organs, and if the water isn’t deep enough for a gator to float, it can suffer pain and even die from the pressure of its own internal weight. Plentiful water helps alligators feel safe and calm in their environment, he adds.

The right temperature is a requirement too. As natives of the U.S. Southeast, alligators are used to living in a warm-to-hot environment, and pet owners may need to use several heat lamps to keep the cold-blooded animals warm, Eschenbrenner says.

Health woes

Because many people keep pet alligators illegally, the animals miss out on routine veterinary care. As a result, serious health problems may go unchecked for years.

Eschenbrenner recalls one alligator rescued from a home in New Mexico that had been kept in a kiddie pool for a decade. The animal was obese, but even so, poor nutrition had stunted its growth and caused dental problems—it was unable to fully close its mouth because the top and bottom jaws were misaligned.

Many pet alligators develop weakened bones because of a nutrient-poor diet, such as hamburger meat or deboned chicken. One alligator rescued in Arizona was so low on calcium that its jaws were “like a rubber band,” Johnson says. Another was so malnourished that it broke its back leg while trying to escape rescuers.

Unnatural surfaces can be harmful: One alligator raised on a glass platform had a disfigured skeleton because of improperly settled bones.

Considering the difficulties of keeping an alligator, much less a healthy one, it’s no surprise that when the animals become too difficult to care for, their owners abandon or kill them—or surrender them to the authorities, Johnson says.

Good homes for gators

There are people trying to make life better for abandoned alligators. For example, the Phoenix Herpetological Society, in Arizona, provides a natural, semi-wild habitat for 15 rescued alligators at its 2.5-acre sanctuary—along with a number of other abandoned, abused, and confiscated reptiles. The facility, which has an on-site reptile clinic and research center, aims to find permanent homes for many of its animals, often sending them to other reputable sanctuaries around the country.

Female crocs lay their eggs in clutches of 20 to 60. After the eggs have incubated for about three months, the mother opens the nest and helps her young out of their shells.

Alligators' heads are shorter and wider than crocodiles'. Although heavy and slow on land, they can ambush their prey from the water by lunging at speeds of 30 miles (48 kilometers) per hour.

Nile crocodiles are the largest crocodilians in Africa, sometimes reaching 20 feet (6 meters) long.

Saved from the brink of extinction, the American alligator now thrives in its native habitat: the swamps and wetlands of the southeastern United States.

Critically endangered, the prehistoric-looking American crocodile struggles to survive in pockets of shrinking habitat.

The largest crocodilians on Earth, saltwater crocs, or "salties," are excellent swimmers and have often been spotted far out at sea.

American alligators are found in freshwater coastal wetlands across the southeastern United States, from Louisiana to the Carolinas.

Mother Nile crocodiles lay their eggs in a buried nest, opening it when high-pitched squeaks are heard from within. The sex of baby crocs is dependent upon the temperature of the nest rather than genetics.

The best solution, Eschenbrenner says, is not to own an alligator in the first place. “I would never have an animal like this as a pet, period.”

A good option for alligator enthusiasts is to appreciate them from a distance by supporting conservation groups or a certified zoo that keeps the animals properly for public education, he says.

Owning one is “doing an injustice to this animal,” Eschenbrenner says. “You’re causing it more harm than good.”

Wildlife Watch is an investigative reporting project between National Geographic Society and National Geographic Partners focusing on wildlife crime and exploitation. Read more Wildlife Watch stories here, and learn more about National Geographic Society’s nonprofit mission at nationalgeographic.org. Send tips, feedback, and story ideas to [email protected].

0 notes

Note

Do you like snakes?

I love snakes! They’re so cool! I love them! They’re so neat and pretty and they’ve got such cool scales and markings and colors and they can climb trees or snuggle or just sit there looking pretty. Or pretty dangerous. But I love them even if they’re the sort you can’t snuggle ‘cos they’ll kill you, or at least be very ticked off.

And I have snuggled with snakes. Once, in high school, my science club got a herpetologist to come and he brought a bunch of snakes, including like half a dozen corn snakes in all kinds of pretty colors. He passed them around, and one wrapped around my arm and shoulder for a bit before it decided it really wanted to be inside my shirt, where it was nice and warm. A little disconcerting at first! But also very cool. :) And I petted a big ball python and a burmese python at an event at the Chicago Herpetological Society once.

But I don’t think I could ever own a snake, even a nice and pretty corn snake, because, y’know, the whole feeding them baby mice thing. *shudder* I’m happy to just look at the ones that belong to other people. And hold them if they’re the kind of snake that doesn’t mind being held. We should go to ReptileFest in April and meet all the pretty snakes. And all the turtles and iguanas and the other cool reptiles too. You should come with me. :)

13 notes

·

View notes

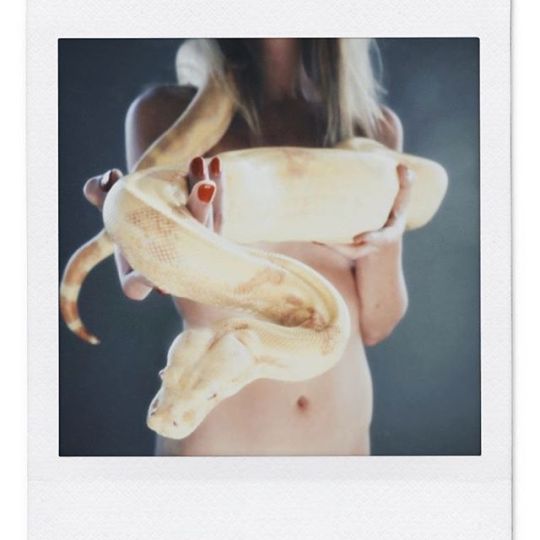

Photo

Ruben the snake!⠀ Ruben has had quite a life for a snake. He was my college pet - he's 9 years old now! He's been to college parties, museum events, educational seminars, herpetology society meetings, he's been in photoshoots, clubs, on stage. He's way more famous than I'll ever be haha! ⠀ Here's a 'polaroid' of one of the shots he was in recently for a benefit for planned parenthood. He was shot by @Collettepark with the model @ktlewitt. Ruben then went to support the art event by again - teaching people snakes are awesome. He's my only pet - he's 6ft long, and i've had him since he was 4 months old! If you work with animals long enough - and get them young enough, you can socialize them to work well in all these situations. Make no mistake though, our teamwork success has everything to do with me understanding his natural behavior and making sure others do too. Ruben is my boy!⠀ if you need him to model - head to the link in my bio, he has a little book going over there. ⠀ .⠀ #snake #snakesofinstagram #reptile #reptilesofinstagram #model #photography #outtake #potd #polariod #coldbloodedcutie #fashion #snakeskin #skin #nude #artistic #plannedparenthood #benefit #art #raismoney #supportartists #chicago #chicagosnake #highrisereptile https://ift.tt/2wuhbnf

0 notes

Text

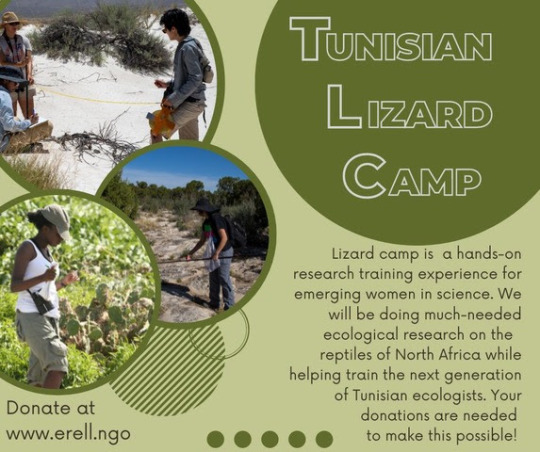

April Monthly Meeting: The Tunisian Big Five - Diverse Lifestyles in Diverse Habitats

This month we have some very special guests giving a talk: Doug Eifler, Maria Eifler, and Makenna Orton of the Erell Institute. Their talk with be about the Tunisian Big Five lizard species (desert monitor, chameleon, sandfish skink, uromastyx, and lacertid Timon pater.) These species inhabit a broad range of habitats and are representative of Tunisia's herpetile diversity.

You can attend the meeting via this Zoom link or in person at the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum if you're local to the Chicago area! And to learn more about the Erell Institute click here!

The meeting will be this Sunday (April 16th) at 2 pm CDT.

#monthly meeting#chicago herpetological society#tunisia#erell institute#women in stem#women in science

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kaiju, Harker, Tandi, and I stopped by a local back to school bash to do some demos and education as part of the Chicago Herpetological Society. Everybody had a great time! The kids loves getting to meet the critters and the teachers asked me to come back to do demos to the science classes later in the semester.

157 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Opening and eating crabs is a challenge for many of us, as we do not know how to rightly use the designated tools. But some animals manage to do it without tools and even without hands! A Thai-Belgian team of biologists, including our colleague and vertebrate animal specialist Olivier Pauwels, recently discovered that the rare freshwater snake Opisthotropis spenceri, which lives in fast-flowing streams in the mountains of northern Thailand, has developed special skills to feed on a locally abundant crab species. The snake explores every nook and cranny of the stream in search of freshly-moulted crabs, whose body is for a short time soft and vulnerable before it hardens again. The snake then coils its body around the defenseless crab, removes and swallows its legs one by one, before opening its body to feed on its entrails. Snakes usually swallow their prey whole, and only a few other cases are known where snakes dismantle their prey before swallowing it. This observation was published in the Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society.

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

how does someone go about getting involved in educational work with their specimens? it's something I've thought about trying myself, but I have just no idea where to start.

The best place to start is to look around or ask about local opportunities. If you have any connections to schools in your area those are a good place to reach out to. My mother works as a school secretary and I’ll hopefully be able to do a program at her school in the future. Also look into joining local groups focused on wildlife. I’ve done work with the Chicago Herpetological Society so far, and I plan on being active with them throughout the remainer of the year. My work with the CHS has been focused on my (living) barred tiger salamanders, Steve and Bucky, since tiger salamanders are considered an ecological indicator species. You might also be able to check with universities about loaning out specimens to them for classes, I’ve been talking to the anthropology department at my old university about letting them use my primate skulls for labs.

I think it also helps to have a general theme or idea in mind already when you do public talks. I admit that the first time I did stuff with my salamanders I sort of BS’d everything because it was a very last minute thing, but I’ve been developing and refining the topic a lot more since then. For osteological specimens I plan on focusing on convergent/divergent evolution. Having a theme or topic already will help sell people on letting you actually give talks.

Best of luck! Feel free to shoot me a DM if you want to talk about it more!

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

How Do We Prevent Pets from Becoming Exotic Invaders?

Outlawing possession does not appear to stem the release of alligators, snakes and other problematic species

By Jim Daley

October 7, 2019

This summer a professional trapper caught an alligator in a lagoon in Chicago’s Humboldt Park, following a weeklong search that drew crowds of onlookers and captured national headlines. Dubbed “Chance the Snapper,” after a local hip-hop artist, the five-foot, three-inch reptile had likely been let loose by an unprepared pet owner, say experts at the Chicago Herpetological Society (CHS). This was no anomaly: pet gators have recently turned up in a backyard pool on Long Island, at a grocery store parking lot in suburban Pittsburgh (the fourth in that area since May) and again in Chicago.

Keeping a pet alligator is illegal in most U.S. states, but an underground market for these and other exotic animals is thriving—and contributing to the proliferation of invasive species in the U.S. and elsewhere. As online markets make it steadily easier to find unconventional pets such as alligators and monkeys, scientists and policy makers are grappling with how to stop the release of these animals in order to prevent new invasives from establishing themselves and threatening still more ecological havoc. New research suggests that simply banning such pets will not solve the problem and that a combination of education, amnesty programs and fines might be a better approach. Many people who release pets may simply be unaware of the dangers—both to the ecosystem and the animals themselves—says Andrew Rhyne, a marine biologist at Roger Williams University who studies the aquarium fish trade. People may think a released animal is “living a happy, productive life. But the external environment is not a happy place for these animals to live, especially if they’re not from the habitat they’re being released into,” he says. “The vast majority of [these] species suffer greatly and die out in the wild.”

EXOTICS TO INVASIVES

Owners sometimes release alligators, as well as other exotic pets such as snakes and certain varieties of aquarium fish, when they prove too big, aggressive or otherwise difficult to handle. But unleashing them on a nonnative habitat risks letting them establish themselves as an invasive species that can disturb local ecosystems. According to one estimate, nearly 85 percent of the 140 nonnative reptiles and amphibians that disrupted food webs in Florida’s coastal waters between the mid-19th century and 2010 are thought to have been introduced by the exotic pet trade.

A study published in June in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment found this trade is already responsible for hundreds of nonnative and invasive species establishing themselves in locations around the world. Examples range from Burmese pythons—which can grow more than 15 feet long and dine on local wildlife in the Florida Everglades—to monk parakeets, whose bulky nests atop utility poles and power substations around the U.S. cause frequent fires and outages. And because of the growth of direct-to-consumer marketplaces on Web sites and social media, “the trade in exotic pets is a growing trend,” both in terms of the number of individual animals and the variety of species kept, says study leader Julie Lockwood, a Rutgers University ecologist. “Together, those increase the chances that this market will lead to an invasion” of an exotic species, she says.

To date, the main way officials have tried to combat the problem is with laws that simply prohibit keeping certain categories of animals as pets. But the effectiveness of this approach is unclear. Even though Illinois has outlawed keeping crocodilians as pets for more than a decade, Chance is just one of many CHS has had to deal with this year alone, says its president Rich Crowley. He likens the problem to illegal fireworks, noting that bans on exotic pets are inconsistent from one state to the next. For Illinois residents, “there’s still a supply that is readily available, legally, across the border” in Indiana, he says. “There are people out there who are willing to take the chance of skirting the law because the reward of keeping [these] animals is worth the risk.”New research published recently in Biological Invasions underscores this point, finding that banning the sale and possession of invasive exotic species in Spain did not reduce their release into urban lakes in and around Barcelona. “For these invasive species, legislation for the management of invasions comes too late,” because they have already established themselves in the local environment, says University of Barcelona ecologist Alberto Maceda-Veiga, the report’s lead author.Phil Goss, president of the U.S. Association of Reptile Keepers, says that instead of blanket bans, he would like to see ways for responsible pet owners to still possess exotic species—with laws targeting the specific problem of releasing animals into the wild. “We’re certainly not against all regulation,” he says. “What we’d like to see is something that will punish actual irresponsible owners first rather than punishing all keepers as a whole.”

TRAINING AND TAGGING

Instead of bans, Maceda-Veiga’s study recommends educating buyers of juvenile exotic animals about how large they will eventually grow and taking a permit-issuing approach that requires potential owners to seek training and accreditation. “You need a driving license to drive a car,” and people should be similarly licensed to keep exotic pets, Maceda-Veiga says. He and his co-authors contend that licensing, combined with microchips that could be implanted in pets to identify owners, could curb illegal releases.Rhyne agrees that giving buyers more information would likely help. “I think the education part is really important,” he says. “We should not assume that the average consumer understands (a) how big the animal will get once it’s an adult and (b) what the harm could be if it got out in the wild.” Crowley concurs and says CHS has worked with municipal authorities to make sure pet owners who might have a crocodilian that is getting too big for the bathtub are referred to the organization for assistance. Also, some state agencies offer alternatives to dumping an animal in the wild that protect owners from legal repercussions. Lockwood says devising responsible ways for owners to relinquish such pets could help. But for this to work, “you need to make it as easy as possible” to turn in an animal, she says. In 2006 Florida’s Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) established an amnesty program that allows owners to surrender their exotic pets with no questions asked. So far more than 6,500 animals have been turned over to the program, says Stephanie Krug, a nonnative-species education and outreach specialist at FWC. A few other states have followed Florida’s lead in establishing amnesty initiatives.

Rhyne says some of the onus for controlling exotic animals should fall on the pet industry itself. “If you don’t regulate yourself and make sure you’re doing your best not to trade in species that are highly invasive, you’re going to create a problem that [lawmakers] are going to fix for you,” he adds. Mike Bober, president of the Pet Industry Joint Advisory Council, says the pet care community is considering ways to proactively address the problem. “We look at that being primarily based in education and partnership,” he says.As for what became of Chance, the erstwhile Windy City denizen is acclimating to his new home at the St. Augustine Alligator Farm Zoological Park in Florida. An aerial photograph of the Humboldt Park lagoon adorns his enclosure—but he is back where he belongs.

0 notes

Photo

I had the privilege capturing these cuties African Spur thigh Tortoises from the Chicago Herpetological Society when I attended the Chicagoland family pet expo 2018 #chicagolandfamilypetexpo #instatortoise #tortoise #tortoiseofinstagram #africanspurredtortoise #tortoiseshell #tortoisesofinstagram #tortoisegram #tortoisesofinstagram #tortoises #turtlesofinstagram #turtle #turtles

#chicagolandfamilypetexpo#tortoiseshell#tortoisegram#turtles#tortoiseofinstagram#tortoise#tortoisesofinstagram#instatortoise#turtle#turtlesofinstagram#africanspurredtortoise#tortoises

0 notes

Text

A complete guide for Ball Python pet care for beginners

Ball pythons (or also known as royal pythons) are medium-sized non-venomous snakes native to Central Africa. They live in savannas and meadows and feed on small rodents. Although not native to the United States, spherical pythons are probably the most popular pet snake in the country.

Are ball pythons good pets for beginners? Ball pythons are the first perfect snake. They are not poisonous, they never grow more than 5 feet long, and have calm tempers. Spherical pythons are easy to care for, are not aggressive and allow normal handling.

We cover what you need to know about keeping your first ball python. You will learn what ball pythons are, how to configure their enclosures, and how to feed them. We will also explain the most common health problems of the ball python and answer the most frequently asked questions.

Python ball (Python Regius) Species information

Ball pythons, scientific name Python regius, are also called real pythons in some parts of the world. They are constrictor snakes, like the boa constrictor. They kill their prey by wrapping it with their bodies and squeezing it to death.

Spherical pythons are native to sub-Saharan Africa. They spend a lot of time on the ground and do not climb trees. Although you will not find spherical pythons in the wild, they are often imported and bred in captivity. Ball pythons get their nickname from their tendency to snuggle into a ball when they feel threatened. Here is more information about spherical pythons.

Are Ball Pythons venonmous?

No, ball pythons are not venomous. As they kill their prey by constriction, there is no need for them to possess venom. They don't have fangs, but they have several small teeth that they use to grab their prey. Therefore, if you have ever suffered a bite from a ball python, it will not harm you. You would bleed, but the bite wouldn't hurt much.

You will wonder about the risk of constriction. However, there is nothing to worry about. Because ball pythons are so small, they would never try to eat you. Ball pythons eat rodents in the wild, and humans are too big for them. Even if a ball python confuses your hand with food, you can easily separate the snake by unrolling it, starting with the tail.

What Ball Python morphs are available?

The wild ball pythons are dark brown to black, with brown spots along the back and sides. In the pet trade, they are called "normal" spherical pythons. Ball python breeders have also created some very interesting colors and patterns playing with the genetics of ball pythons. These are called "morphs."

There are literally hundreds of different ball python morphs out there, so we can't list them all here. However, we will describe some of the most popular morphs, as well as our personal favorites.

Ball Python Morph Identification of colors and brands Albino Ball Python: They have no brown or black pigment (melanin). They appear white with yellow spots: they are pale lavender, with bright yellow spots. Some bananas are also stamped with small black dots: Axanthic Ball Python, which lacks yellow pigmentation. The spherical axántic pythons are black, with gray and white spots. Spherical pastel python: they are dark brown to black, with large bright yellow spots. spherical spider python: they are brown with distinctive markings of black lines and "spider veins". Piebald spherical python: they have normal markings and color, with large white sections without pigment along with their bodies.

It is also possible to breed different morphs together, to produce a ball python that has features of each. For example, the "Axant Spider" ball pythons have a distinctive spider pattern, but they are completely black and white. A ball python «Banana Pied» has the same color and markings as a banana ball python, interspersed with large white spots.

How do ball pythons grow?

One of the attractive parts of owning pythons is the fact that they remain relatively small. On average, male spherical pythons reach 2 to 3 feet long. Females, on the other hand, can reach 3-5 feet. They will not exceed your welcome in the same way as a cross-linked python.

You may wonder: when do spherical pythons stop growing? Actually, like most snakes, ball pythons continue to grow throughout their lives. However, they make almost all of this growth in the first years. Juveniles grow extremely fast but reach almost their maximum size at 4 years. For the rest of their lives, they grow very slowly.

Although males and females differ in size, the life expectancy of the ball python for males and females is the same. In nature, they tend to live for around ten years. However, a well-treated captive ball python could live to be 20 or 30 years old.

The oldest recorded ball python was 48 years old, according to the Chicago Herpetological Society. He lived at the Philadelphia Zoo from 1945 until his death in 1992. Interestingly, although he was old, he did not grow much more than the "size of a young adult" throughout his long life.

Do you like to be manipulated Ball Pythons?

It would be anthropomorphic to say that any snake "likes" to be manipulated. Snakes are solitary creatures and do not relate or prepare with each other in nature. Therefore, they do not enjoy manipulation. Managing our snakes is purely for our enjoyment as snake lovers.

However, as snakes go, ball pythons are incredibly docile. Captive-raised ball pythons typically do not see humans as a threat and tolerate handling very well. As long as you hold them properly (keeping them a third and two thirds along their body), they will be very happy to be in your arms. Spherical pythons are of good character and do not usually whistle or show signs of aggressiveness with their caregivers. In any case, they are a bit shy.

Requirements of the Ball Python nursery

Now that you know the basics of the ball python, let's get into your care requirements. The first topic we will cover is the nursery - where your ball python will live. There are many elements that must be tuned to form the perfect nursery.

Ball python box

When choosing an enclosure for your ball python, there are many things to consider. The first is size. Your ball python will need space to fully stretch. Therefore, if your snake is 2 feet long, the enclosure must also be at least 2 feet long.

This means that if your snake is a juvenile, it will have to replace its enclosure as it grows. You may be tempted to buy a massive enclosure to "grow", but this is a mistake. A baby snake will feel lost and terrified in an enclosure that is too large.

For this reason, it is generally a good idea, to start with, a plastic bathtub with a lid. These are much cheaper to replace as your snake grows, compared to decorative glass or wood cages.

There are many benefits to plastic bathtubs:

They are light and easy to move.

Its closing lids make it easy to) keep moisture and b) prevent the snake from escaping.

Plastic bathtubs cling to heat much better than glass tanks.

Plastic is easy to clean and is not porous, which gives it an advantage over wood.

The only drawback of plastic bathtubs is that they are not as attractive or "elegant" as glass or wood nurseries. The choice is yours.

Temperature and humidity requirements of the ball python

Although spherical pythons come from a tropical part of the world (central sub-Saharan Africa), they do not live in the rainforest. This means that its moisture requirements are not as demanding as other species of tropical snakes, such as the boa constrictor.

Ball pythons generally require 50-60% humidity throughout their enclosure.

A large container of water contained inside the nursery should be sufficient to keep the humidity high enough. It will also meet the other water needs of your ball python (drink and soak).

Use a hygrometer to control humidity levels. If it falls below 50%, you can spray the inside of the enclosure once a day. Keeping a skin box full of wet sphagnum moss can also help.

With regard to heating, you have several options:

Thermal mat

Thermal tape

Ceramic heat bulb (only glass tanks, as they can melt plastic caps)

Whichever way you choose to heat your snake's enclosure, use it only on one side of the enclosure. This will create a cold end and a warm end, allowing your snake to regulate body temperature.

The cold end of the tank should be at 70-80 degrees Fahrenheit, and the hot end should be around 90-95. Control the temperature closely with a thermometer. If possible with the chosen heating method, use a thermostat so that the temperature adjusts automatically.

Ball Python Substrate

Although spherical pythons enjoy moist air, they don't do well with a wet substrate. In the wild, they spend most of their time in savannas and grasslands. We recommend that you avoid substrates that retain moisture, such as cypress mulch. A wet substrate can result in lime rot.

The recommended substrate for ball pythons is poplar chips.

Aspen has many benefits:

It does not retain moisture, so it provides the perfect "ground" for spherical pythons

.

It is cheap and available in almost all reptile stores and online suppliers

It is easy to clean. You remove the area where you have peed or poop and you can leave the rest.

Many new snake owners choose the newspaper to use on the floor of the enclosure. Although they are also cheap, they cannot be cleaned. If the snake pisses in the newspaper, the entire substrate must be replaced. Some people worry that newspaper ink may harm snakes, but it is not scientifically proven in one way or another, so use it at your own risk.

Although wild ball pythons hide underground, they don't dig their own burrows. They use the burrows of other animals, such as rodents. They can even hang out on termite mounds. For this reason, digging is not a behavior that ball pythons typically exhibit in captivity. You do not have to provide a thick layer of substrate - about an inch will suffice.

Nursery accessories and cleaning

There are some accessories that you should include in the nursery of your ball python and others that are optional.

Hide. Pythons need a place to hide and feel safe. You must provide at least two leather cases - one at the hot end, and one at the cold end. The box should be large enough for your snake to curl inside, while small enough to feel "comfortable" and safe. You can buy snake leathers made on purpose or use a cardboard or plastic box with a trimmed entry hole.

Bowl of water. Your snake will need to drink, of course. Many ball pythons also enjoy snuggling in their water bowls for bathing. Choose a bowl that is at least as large as your snake and easy to clean.

Decoration. These are optional, but provide enrichment for your snake, and help mimic a natural environment. You can use rocks, hollow logs, branches, artificial foliage, and plants. We do not recommend the use of live plants, as the soil can harbor bacteria and parasites.

When you add accessories to your nursery, leave enough space for your snake to stretch and slide. However, too much space can be intimidating, so make sure your snake has many places to hide.

Cleaning the nursery of your ball python

It is crucial that you keep the nursery of your spherical python clean. Dirt, feces, and urine can harbor bacteria. This could result in your ball python developing an infection and getting sick.

Every day, perform a review of your snake's enclosure to clean it. Remove the bowl of water from the snake, rub it with hot water and soap and disinfect it. A popular disinfectant option is a chlorhexidine.

Then, examine the cage for urates (solid urine) or feces. Remove waste products along with any substrate they have touched. Also, eliminate any food that has not eaten or fallen skin.

At least once every two weeks, thoroughly clean the nursery.

Place your snake in a temporary box for this.

Remove and discard the entire substrate.

Remove all accessories from the tank. Clean and disinfect them individually, and let them dry.

Wash the tank with soap and water, disinfect it with chlorhexidine and let it dry.

Place a fresh substrate inside the tank along with the clean accessories and then reinsert the snake.

Ball Python feeding guide

Now that you know how to house and care for your ball python, let's move on to another important issue: food. We will teach you how to choose the appropriate food for your ball python, and the details of the feeding process.

What do Ball Pythons eat?

The diet of a ball python consists mainly of mammals. In their natural habitat, spherical pythons feed on rodents that live in African grasslands. For example, this may include soft-haired African rats, Gambia rats, hairy rats, gerbils, and striped grass mice.

Occasionally, spherical pythons can also eat birds, although this is not their first choice of prey. The spherical pythons feed exclusively on endothermic creatures (warm-blooded), with the help of their facial pits with an infrared sensor.

In captivity, spherical pythons subsist well on a diet of rats and mice. These rodents contain all the nutrients that ball pythons need, so there is no need to supplement their diet.

We would always recommend feeding rats and mice frozen and thawed, rather than live prey. This is because living prey can often defend themselves, hurting or even killing the snake. There are many online providers that sell frozen rodents in a variety of sizes, from the "pinkie" (newborn) to the "jumbo".

You can use mice to start, but your ball python can eventually overcome them. We find it easier to use rats from the beginning, to avoid the problems that sometimes occur when changing. Spherical pythons tend to "print" on a particular food source and refuse to eat anything else.

How to feed Ball Python frozen mice and rats

Feeding your ball python begins with the selection of a rodent of appropriate size. The dam must be about as wide as your ball python. If it is larger or smaller, your snake may not recognize it as food.

Once you have a food source, here is how to feed your ball python.

Defrost the rodent in room temperature water. This may take 10 minutes to an hour, depending on the size of the rodent. Never use hot water, as the rodent may explode.

Once the rodent is completely thawed, soak it in a bowl of warm water to heat it. Spherical pythons find it easier to recognize their prey when they are hot.

Remove your snake from its nursery and place it inside a temporary feeding box. This is optional, but we recommend it. First, it means that your snake will avoid ingesting any substrate. Second, your snake will not associate your nursery with food. This means that your snake is less likely to confuse it with its prey when you approach it to manipulate it or to clean the nursery.

Offer the rodent to your snake, using a pair of long-handled pliers. Do not use your hands, as your snake can confuse them with food. It may be useful to "move" the rodent, imitate a live animal.

Once her ball python has taken the rodent, she will narrow it by wrapping it with her body. Once you are satisfied that you are "dead," you will swallow it whole. Leave it at least one hour before putting it back in the nursery. Avoid handling the snake for 48 hours after feeding, as this could cause regurgitation.

How often should I feed my ball python?

Many ball pythons are voracious eaters that devour food when available. A study in Physiology and Behavior found that spherical pythons feel hungry again as soon as 24 hours after eating.

Although this prevents wild ball pythons from starving, it means that captive ball pythons would overeat. This could lead to excessive weight gain, so it is important that you keep your snake on a feeding schedule.

As a general rule, juvenile ball pythons need to eat more regularly than adults. This is simply because they are growing rapidly and need additional nutrients. Spherical pythons less than one-year-old should be fed with a rodent of the appropriate size every 5 to 7 days. For ball pythons of one year (1-2 years old), the feeding can be reduced to once every 7 to 10 days.

Once the python reaches two years of age, it is when it is generally considered an adult. At this point, you have two options. You can continue feeding them with smaller meals every 7-10 days, or you can switch to a larger rodent every 2-3 weeks.

Each snake is different, so play with your feeding schedule until you find something that works. Some snakes do not recognize smaller rodents as food, while others prefer them.

Why does my ball python not eat?

If there is a disadvantage of pythons, they can be very fussy when eating. This is because, in nature, they feed on a variety of animals that we cannot offer them. All of them are brown, while the rats and mice that we offer are usually white.

Ball pythons can, with patience, be trained to feed on white mice and rats successfully. If you have bought your python from a reputable breeder, they should have already done this. So, if your python is not eating, there is probably another reason.

For example:

Your snake could be starting to come off. Like most snakes, pythons do not eat while they are moving.

The dam may be too large or too small. If your python thinks the rodent is too big, it won't try to eat it. If it's too small, it won't seem worth eating.

The nursery can be too cold, too hot, too wet or too wet.

Your ball python could be sick or stressed.

If none is applied, it is likely that your ball python is not hungry. Ball pythons tend to skip a meal once in a while, and this is normal. Remove the dam and try again in a few days. It can help offer prey overnight, as ball pythons are naturally nocturnal.

It can also help offer live rodents instead of pre-killing them. However, if you decide to do this, be sure to closely monitor the feeding session in case the rodent attacks your snake.

Ball Python Health Issues

Like all snakes - and all animals - spherical pythons may be susceptible to certain health problems. Fortunately, most common health problems are completely treatable.

Weight problems If your snake is overweight, you will notice large deposits of fat on each side of the spine, or "fat rolls" when the snake curls up. If your snake is too thin, your spine will protrude prominently, giving it a triangular body shape. You may also notice that the skin is loose.

Respiratory infections are reasonably common in snakes. They are indicated by sibilant or crackling sounds when breathing, breathing through the mouth and discharge from the mouth or nose. Respiratory infections can be caused by viruses, according to research in Virology. However, they can also be bacterial or fungal in nature.

Parasites, both internal and external, are more frequent in snakes caught in the wild. The most common parasite is mites. If your snake has mites, you will notice small insects hanging from the scales of your snake.

The rot of the mouth and the scale Rotting scales (brown, flaked scales) usually affects the abdomen and occurs when the snake's environment is too wet. Oral rot can be the result of trauma or another disease. You will notice a red and swollen mouth, excessive saliva and pus.

Burns can be a problem when your heat source malfunctions or is too high. They are more common when using a thermal mat. If your snake has a burn, you will notice redness, scaling of scales and open wounds in severe cases.

Neurological problems may be present in certain ball python morphs (such as spider, champagne and woman) due to genetic problems. They are presented as a "head wobble" when moving, which can be mild to severe.

Of course, this list is not exhaustive. If your snake refuses to eat, seems apathetic or shows any physical signs of illness or harm, take it to a veterinarian. Do not try to treat anything by yourself if you are not a professional.

Frequently asked questions about Ball Python

How to determine the gender of a ball python?

In ball pythons, the most obvious indicator of sex is size. Females tend to grow more than males, to carry as many eggs as possible. As adults, males remain around 2 to 3 feet, while females can reach 3 to 5 feet.

However, when they are babies, both genders start being equally small. If you buy your snake from a reputable breeder, they should be able to tell you the sex of the snake. If not, or if you want to confirm it, there are two ways to do it.

The sewer probe consists of inserting a thin metal rod into the snake's sewer (genital cavity). In males, the probe penetrates much more deeply than in females (beyond the width of the snake's body).

The sewer burst involves holding the snake on both sides of the cloaca and causing its hemipenes (male sexual organs) to move smoothly using a swinging motion with the thumb. In women, nothing will come out.

These practices should only be carried out by snake enthusiasts and experienced herpetologists. If you are a beginner, never try these methods without someone with experience guiding you.

How often do ball pythons lose their skin?

Like all snakes, ball pythons lose their skin occasionally. Hair loss is more frequent in juveniles, as they grow faster. Young ball pythons tend to break off every 3 or 4 weeks. Adult ball pythons (over one year of age) only detach approximately once every 6 to 8 weeks.

When your snake is about to start shedding, your skin will look darker and dull than normal. Then, your eyes will cloud and look blue. At this point, it may be useful to increase the humidity of the enclosure. From this moment, avoid manipulating and feeding your snake. You will lose your appetite and may become lonely during the spoiling process.

After about a week, your eyes will clear and return to normal. A few days later, the ball python will start molting. He will begin the process by pushing his nose against something and eventually leave his old skin completely.

Your skin should come out in one piece, complete with eye caps and the tip of the tail. If the skin remains attached, it is a sign that the humidity was too low. Giving your python a gentle bath in warm water can help remove the clogged shed.

Why is my ball python not pooping?

As a general rule, ball pythons will defecate after every 2-4 meals. They release their wastes at once, instead of in small quantities and often. It is not uncommon for ball pythons to spend a month, or even two, without pooping. Some ball pythons wait until they come off.

While your snake is eating and behaving normally, with no signs of illness, it is not a cause for concern. However, if you are worried about constipation, try soaking your snake in warm water (around 90 degrees Fahrenheit). This works like a laxative, heating your digestive system and helping things run their course. Do not be surprised if your snake defecates in the water - be sure to remove it immediately.

If your spherical python spends more than 12 weeks without pooping, or if you notice any other sign of poor health, take it to a veterinarian.

Why is my ball python trying to escape?

Even domesticated snakes, such as pythons, are wild animals in the background. No snake finds it natural to live in a small enclosure. So, if they have the opportunity to leave their nursery, they will. This does not necessarily mean that you are not taking care of it properly - snakes naturally want to explore.

However, your snake should not always be pressing against the glass, trying to find a way out. If your snake seems unusually obsessed with escape, seems stressed or refuses food, it is possible that something is wrong.

For example:

The nursery can be too hot or cold, too wet or too dry.

The enclosure may be too empty, making your snake feel insecure. Try adding more skins and artificial plants to give you more coverage.

The box may be too small, causing tension. As a general rule, your snake's nursery should be about as long as she is, to give her space to stretch.

You may not be cleaning the enclosure well (or often enough). In nature, ball pythons would find a new den when the old one begins to smell too much of the snake. Be sure to thoroughly clean and disinfect not only the cage but everything in it.

Your snake may be hungry and is not recognizing its offerings as suitable prey for whatever reason. Try a smaller rodent.

If your snake appears to be sick, or if you cannot find out what the problem is, take it to a veterinarian.

Can ball pythons see in the dark?

Something you may have heard about snakes is that your vision is not so great. This is true if we compare his vision with ours. Ball pythons can only detect a limited range of colors, and cannot capture the details of inanimate objects like us. Instead, their vision is adjusted to detect the movement of prey and predators.

Many snakes are nocturnal (they hunt at night), which means that too….

0 notes

Text

google i promise you i'm searching for the chicago herpetology society NOT the chicago herpes society

0 notes