#counter-historiographies

Text

camden art centre, london / public knowledge: 'oei' / october 27

camden art centre, london / public knowledge: ‘oei’ / october 27

Camden Art Centre / Public Knowledge: OEI / October 27 / 19:00–21:00

Thursday October 27, 19:00-21:00

Camden Art Centre

Arkwright Road

London NW3 6DG

United Kingdom

This episode of Public Knowledge will comprise of a temporary display of publications and related ephemera by Jonas (J) Magnusson and Cecilia Grönberg.

Jonas (J) Magnusson and Cecilia Grönberg are the founders of OEI, a…

View On WordPress

#aesthetic documents#art#bookworks#Camden Art Centre#Cecilia Grönberg#counter-historiographies#critical investigations#documents#ecologies#infrastructural poetics#investigative poetry#Jonas (J) Magnusson#localities#new epistemologies#OEI#Paul Finn#poetry#theoretical and poetological essays#theory#visual culture

0 notes

Text

one of the biggest issues with the current misinformation and/or propaganda discourses is that a lot of people on some level hold the idea that there's a linear separation between "media that is Propaganda" and "True Media, which is Correct and Pure," and that is fundamentally not how the news works, or how history works, or how historiography works. Some news and history is certainly working to push particular points more than others, and not all aspects of the political equation bear equal validity, but a lot of people are refusing to engage with the fact that all news and all media needs to be engaged with critically, and that "read from a variety of sources" isn't a conservative psyop but an attempt to try to counter the fact that every journalist ever - every person every, and certainly every twenty something tiktoker ever - has certain biases. there is no linear, singular, pure "truth." in fact, the acceptance of the idea that there can be some media that is wholly pure versus others that is nothing but pure propaganda is exactly how people buy into propaganda to begin with - because it presents a clean, straightforward, and seemingly just explanation for the world

#people wanting One Book to read about the situation and suddenly learning how historiography works [eyes emoji]#You can't just comprehend things as True Facts#Which are Factually Correct#Versus Bias. which is evil people controling everything#context & sources and methods are actually massively important ehre#there is no one true response you're going to get for anything

232 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Black Rider: Nikolaos Plastiras

Colonel Nikólaos Plastiras (1883 - 1953) was a general and politician, who served twice as the Prime Minister of Greece. He was a politically conflicting or, even, confusing leader who however was very popular at his time. Contemporary historiography evaluates Plastiras as neither a particularly competent politician nor perceptive enough for such a position, however historians agree he was a rare example of a prominent man being very notable for his sense of honour, lawfulness and temperance.

Plastiras fought in the Macedonian Struggle, the Balkan Wars, the National Defense Movement (against the King), World War I, alongside the Allies in the war of the Red and the White Army in Ukraine. Due to his distinction in battle, he earned the name "Ο Μαύρος Καβαλάρης" (O Mávros Kavaláris), "the Black Rider".

Source: mixanitouxronou.gr

In 1922, Plastiras' Regiment was transferred to Smyrna (Izmir) during the Greco-Turkish War. Plastiras was the only anti-King officer that was not dismissed from the army, simply because his Regiment threatened they wouldn't fight under any other commander. While the war ended with Greece's defeat, Plastiras was singled out and called by the Turks as "Kara Biber" (Black Pepper) and his Regiment as "Şeytanın Askerleri" (the Satan's Army).

After the defeat, Plastiras along with Colonel Stylianos Gonatas and Commander Phokas organized the September 1922 Revolution which led to King Constantine I's resignation and the return of the exiled politician Eleftherios Venizelos. His most controversial moment was the "Trial of the Six" (Η Δίκη των Έξι) were six officers were deemed as the major culprits of the disastrous war for Greece, partly due to their blind devotion to the King and their contempt against the popularity of Venizelos. They were condemned to death.

Once, his brother, Giorgos Plastiras, 60 years old at that point, asked for a job in a FIX beer factory. Hearing his surname, they asked him whether he was related to the PM. His brother admitted it but begged them to keep it a secret from him. They agreed and hired him immediately. However, as it happens, a few days later it was all over the news. Plastiras, furious, called his brother to his house and scolded him for getting a job relying on the family name. He counter-proposed that if his brother had financial issues, he should stay with him and share the food.

Plastiras was chronically ill and he lived in a tiny house in Mets (unthinkable for a politician and twice PM). Once, somebody suggested to set up a landline phone for him. Plastiras refused. "How do you even suggest this? Greece will be in poverty while I get to enjoy my phone!?"

Plastiras adopted five orphans from men who fell in battle. He never married and had no biological children.

One night of August 1922, during the Greek army's retreat from Asia Minor, the soldiers were so exhausted that they all fell asleep. When they woke up the next morning, they saw Plastiras on his horse, guarding them. They asked him, "Sir, you - our commander - are standing guard over us?!". Plastiras replied; "I am riding and I am well rested. You travel on foot and carry the supplies. If I don't protect you, then who ought to?"

The publisher of two prominent to this day newspapers (ΒΗΜΑ and ΝΕΑ) once gifted an expensive golden pen to Plastiras. Plastiras refused the gift. When his secretary argued that the publisher might get offended, Plastiras insisted. "I do not need to sign in gold. My little pen is enough. I don't want gifts. For those who make gifts often expect 'gifts in return' (=implied he suspected bribery)".

Plastiras was once visited by Queen Frederica of Greece (daughter-in-law of the king he so fought). She was shocked by the state of his humble home. She asked him why he was sleeping in a cheap camp bed. Plastiras replied that he was used to it since his military days and that many people in the country lived in far worse conditions after all.

Nikolaos Plastiras slept with three frames on the wall over his bed; an icon of Saint Nicholas (his namesake), a painting of French Revolutionists in 1789 and an image of Eleftherios Venizelos!

Plastiras' will to an adopted daughter included the following, which were all his possessions at the time of his death: 216 drachmas, a 10 dollar bill and a note reading "All for Greece". There was also a military receipt charging him with 8 drachmas for a bed he'd lost during the wars. The receipt was accompanied with the amount of money required, with Plastira's requirement to be granted to the public sector, so that he wouldn't die "owing to the Fatherland".

Plastiras was a centrist who often collaborated with liberals and leftists at a time the left was tragically marginalised, at least to the degree that didn’t threaten his own position much. He was likely Venizelos' ultimate fanboy, he was a fierce anti-royalist and loathed the dictatorship of Metaxas. He tried to prevent the Civil War but failed. He was the first one to use the term "Civil War" at a time when others still called it "bandit war", to put the entire blame on the communists. During the war, Plastiras condemned both the Left and the Right for their actions which led to "kin killing kin". As a politician, Plastiras was a pacifist wishing for the unity of the Greek people, but he did not succeed much.

After his death, his body was found to have 27 sword scars and 9 wounds from bullets. His heart was removed and preserved. It was wrapped in a Greek flag and sent to his homeland, Karditsa, as was his wish. His heart is in the Folk Museum of Karditsa.

His heart is kept in a golden capsule in the museum.

Tavropós lake, the lake of Karditsa and a famous artificial lake of Thessaly, was attributed to him. Once, Plastiras was visiting his home Karditsa during severe rainfalls that caused destructive floods in the region. Plastiras looked at the flooded region and said: "This place will become a lake someday". The project for the creation of the lake started a few years later. The lake's actual name is Lake of Tavropós but it is best known as Plastiras' Lake.

Plastiras Lake

#greece#europe#history#Greek history#people#European history#20th century#Greek people#modern Greek history#nikolaos plastiras

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

CATALYST JOURNAL

W. E. B. Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction in America, 1860–1880 is one of the greatest modern studies of revolution and counterrevolution. While it deserves its place alongside the classics, it is also an extraordinary example of a materialist and class analysis of race under capitalism. In recent years, the latter aspect of the book has been obscured and even denied. This essay seeks to restore Du Bois’s great work to its rightful place on both counts.

W. E. B. Du Bois’s magnum opus, Black Reconstruction in America, 1860–1880, published in 1935, is one of the greatest scholarly studies of revolution and counterrevolution.1 It deserves a place on one’s bookshelf next to other modern classics, including Leon Trotsky’s History of the Russian Revolution, C. L. R. James’s The Black Jacobins, Georges Lefebvre’s The Coming of the French Revolution, and Karl Marx’s Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. Scholars of revolutions, unfortunately, have not usually considered the US Civil War to be one of the great social revolutions of the modern era, akin to the French, Russian, and Chinese revolutions. Many readers, in fact, view Du Bois’s book much more narrowly, as a response to white-supremacist histories of the Reconstruction era (1865–76) and, more particularly, a defense of the role of African American politicians — and the black voters who elected them — in the Southern state governments of that time. Du Bois does present such a defense, but Black Reconstruction offers much, much more than this.

Black Reconstruction is not only a towering work of history but also a work firmly embedded in the Marxist tradition. Du Bois reinterprets the Civil War as a social and political revolution “from below” — a workers’ revolution — that brought about the overthrow of both slavery and the Confederate state, thereby opening a door to interracial democracy in the South. The book then reinterprets the subsequent overthrow of this democracy as a class-based counterrevolution that destroyed the possibility of freedom for half the Southern working class and imposed a “dictatorship of capital” that brought about “an exploitation of labor unparalleled in modern times.”2

But why should one read Black Reconstruction in the twenty-first century? In short, because Du Bois is writing about issues that remain of tremendous political importance, including the nature of racial oppression and the racism of white workers. Unlike most contemporary analysts of race, moreover, Du Bois approaches these issues from the perspective of political economy. He rejects an approach to racial oppression that starts with prejudice, discrimination, or culture, trying instead to dig beneath these and understand how they are rooted in the material interests of different classes. Instead of insisting on the separation of race from class, as so many liberals do, Du Bois insists on their intimate connection.3

Black Reconstruction is rightly famous for stressing the collective agency of enslaved people in winning their own freedom and for its impassioned rebuttal of racist historiography. What has been less emphasized is the way in which Du Bois very explicitly rejects analyses of the Civil War and Reconstruction that emphasize race and racism as the primary drivers of historical events. Racism certainly played a hugely important role in that era, Du Bois argues, but it was a product of — and usually disguised — another, more powerful force: capitalism. More specifically, Du Bois argues in Black Reconstruction that two characteristic features of capitalism — capitalists’ competition for labor and workers’ competition for jobs — are the root cause of conflicts that seem to be driven by racism.

This perspective on Du Bois’s masterpiece runs counter to some influential interpretations of his work. Not surprisingly, there is resistance in some quarters to stating plainly that Black Reconstruction is a work of Marxism. Many people who come to Black Reconstruction for the first time are not expecting to read a Marxist text. They have most likely read Du Bois’s earlier collection of essays, The Souls of Black Folk, which precedes his turn to Marxism by three decades.4 While a number of authors do recognize Du Bois’s Marxism,5 many others deny that Black Reconstruction or his subsequent writings are Marxist. In 1983, for example, Cedric Robinson described Du Bois as a “sympathetic critic of Marxism.”6 Gerald Horne’s 1986 book examines in great detail Du Bois’s involvement in leftist (mainly Communist) causes after World War II, but he never offers an opinion as to whether Du Bois was a Marxist.7 And Manning Marable’s book on Du Bois, published just a few months later, portrays him as a “radical democrat” — although Marable later suggested that Du Bois might usefully be viewed as part of the “Western Marxist” tradition.8

More recently, a group of “Du Boisian” sociologists recognizes that Du Bois integrates some elements of Marxist thinking into his worldview. But according to these writers, not only is Du Bois not a Marxist but his ideas clearly transcend Marx’s. Marx gave theoretical primacy to class, they say, whereas Du Bois grasped the “intersectionality” of class and race, emphasizing their connections while giving theoretical primacy, by implication, to neither.9 According to these writers, this theoretical move allowed Du Bois, unlike Marx and his followers, they claim, to understand colonialism, the ways in which race “fractures” class consciousness, and racial oppression generally.10

In this essay, I argue that these “Du Boisians” and others who deny Du Bois’s Marxism are wrong. Du Bois actually does give theoretical primacy to capitalism. In both Black Reconstruction and his subsequent writings, Du Bois repeatedly emphasizes how racial oppression is a product of capitalism. Time and again, furthermore, Du Bois takes issue with what we would today call “race reductionism,” that is, attempts to explain historical events primarily in terms of race. His rejection of race reductionism only deepened in the years after Black Reconstruction’s publication.

After 1935, in short, “Du Boisianism” is Marxism. Du Bois’s failure lay not in the fact that he embraced a Marxist orientation but that he came to uncritically support Soviet authoritarianism. This was perhaps the greatest tragedy, in my view, of Du Bois’s long life. But the main point of this essay is to show that, despite all efforts to ignore or deny his Marxism, Black Reconstruction stands as a brilliant work of class analysis.

BLACK RECONSTRUCTION IN AMERICA

Du Bois’s turn toward Marxism occurred rather late in his life, shortly before the publication of Black Reconstruction. His trip to the Soviet Union in 1926, months before Joseph Stalin’s consolidation of power, certainly pushed him in this direction. “Never before in life,” writes his biographer David Levering Lewis, “had he been as stirred as he would be by two months in Russia.”11 Du Bois traveled more than two thousand miles across the Soviet Union, “finding everywhere … signs of a new egalitarian social order that until then he had only dreamt might be possible.”12 “I may be partially deceived and half-informed,” Du Bois wrote at the time. “But if what I have seen with my own eyes and heard with my ears in Russia is Bolshevism, I am a Bolshevik.”13 (Du Bois would visit the Soviet Union again in 1936, 1949, and 1958.)

Du Bois later wrote that his trip to the Soviet Union led him to question “our American Negro belief that the right to vote would give us work and decent wage,” or would abolish illiteracy or “decrease our sickness and crime.”14 Only a revolution, by implication, could attain these ends. Du Bois also now believed that “letting a few of our capitalists share with whites in the exploitation of our masses, would never be a solution of our problem.”15 Black liberation was impossible, in sum, so long as the United States remained a capitalist society, and “black capitalism” was a dead end.

Du Bois had been broadly familiar with Marxist ideas since his graduate student days at Harvard and in Berlin. But it was not until 1933, in the midst of the greatest crisis of capitalism in world history, that Du Bois began conscientiously to study Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Vladimir Lenin. He was then sixty-five years old. As Lewis writes, Du Bois fell hard for Marxist analysis:

Like so many intellectuals in the thirties who broadcast Marxism as a verifiable science of society, the Atlanta professor was mesmerized by dialectical materialism. Calling Marx the “greatest figure in the science of modern industry,” Du Bois seemed to rediscover with the avidity of a gifted graduate student the thinker who Frank Taussing, his Harvard economics professor, had smugly ignored. Marx made history make sense — or more sense, Du Bois came to believe, than all other analytical systems.16

Du Bois was prodded to master Marxist theory by the rise of a group of so-called Young Turks within the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the civil rights organization he helped found. These young scholar-activists, including Abram Harris, Ralph Bunche, and E. Franklin Frazier (all members or soon-to-be members of the Howard University faculty) “were attempting to shift the Negro intelligentsia’s focus on race to an analysis of the economics of class.”17 All were convinced that a powerful interracial labor movement was necessary to smash racial oppression, and they were critical of the NAACP for its lack of an economic program. Members of this group would offer advice to Du Bois about which texts were essential for him to read. Harris’s book, The Black Worker: The Negro and the Labor Movement, coauthored with Sterling Spero, proved particularly influential; it was no coincidence that Du Bois titled the first chapter of Black Reconstruction “The Black Worker.”18 (I discuss the precise significance of this below.)

(Continue Reading)

#politics#the left#w. e. b. du bois#race#class#capitalism#racism#black history#black history month#history#marxism#socialism#democratic socialism#catalyst#catalyst journal

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'd love to read your thoughts on powerful/badass/interesting medieval queens! I love the Queens of Infamy series on longreads. com, if you're familiar with it. Sending extra love and hugs. <3

Aha, thanks dear. It is much needed. I am sending you hugs in return.

As for badass medieval queens: they're obviously fun to read about, and most people with a passing acquaintance of history will know the most famous ones (Empress Matilda, Eleanor of Aquitaine, Isabella of France, Catherine de Medici, etc etc). However, as a historian who works on (among other things) medieval social and gender history, one of my chief focuses is getting people to think about all medieval women differently, not just the well-known royal ones. We all discard the "great men and European kings are the only people who played a role in medieval history and/or had influence in the world before modernity" hypothesis, and rightly so. But I feel as if the fetishizing of certain medieval queens, where the modern historiography and/or popular history points at them and goes, "LOOK HOW AWESOME THIS ONE WOMAN MANAGED TO BE IN A TERRIBLE RAPEY PATRIARCHAL WORLD!!!" is... to say the least, somewhat wrong-headed.

This is because it promotes the "exceptional woman" theory of history, where it is implied that one woman with superlative personal qualities managed to overcome the limits of patriarchal medieval society, and that all other women who weren't as "gifted" didn't do the same. You may recognize this as an offshoot of the "Extraordinary Negro" racist pseudoscience of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, wherein it was proposed that a few "superior" African-Americans could become almost (if not quite) culturally, intellectually, and socially white, overcoming the limits of their "inferior" race in these isolated special cases. If you can doubtless easily see why that is hella racist, you can also understand why applying the same framework to medieval women is equally ridiculous, reductive, and sexist.

Likewise, there is a lot of recent scholarship that strives to finally discredit this hypothesis once and for all, such as Medieval Elite Women and the Exercise of Power 1100--1400: Moving Beyond the Exceptionalist Debate. Likewise, somewhat appropriately given what has happened today and the mustering of informal female social networks to effectively counter an unfavorable legal climate (once again, if anyone tells me Things Were So Much Worse Back Then For Women, I will punch something), the study of medieval women in community shows that they had collective as well as individual agency. As Women and Community in Medieval and Early Modern Iberia puts it:

First, the emphasis on communities moves us firmly past any narrative of the exceptional woman who found ways to engage in independent political, social, or economic activity within otherwise constraining legal and social norms. Women, both as individuals and as groups, had the knowledge and skills to successfully interact with a variety of communities, and even create new ones when necessary. These communities also reveal the degree to which communities were structured around women's agency. [....] By moving beyond the binary of inclusion/exclusion, these authors acknowledge the ability of patriarchal norms to constrain women's activity and at the same time, for women to take action on behalf of themselves and their families.

This topic is likewise explored in Relations of Power: Women's Networks in the Middle Ages, and others that I can't think of right now. Anyway, this was a long-winded way of saying that while I love me a good badass medieval queen as much as anyone, that often comes with the prevailing stereotype that queens were the only medieval women able to wield any power at all (and then only if they were personally motivated to do so) and that therefore they're the only ones who are "interesting" or worth learning about. This obscures a lot of the important work that has been done on ordinary medieval women, their lives, and their networks of influence, and likewise props up other damaging myths about the Middle Ages that are continuing to be repeated today. So yes.

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

i was reading vasudha pande's kumaun histories and identities (here kumaun means the kumaun division of British India which included both british-garhwal and kumaun districts) and the whole time i was wow these were exactly my thoughts on historiography of Uttarakhand. britishers deliberately built the whole noble savage imagery for pahadi people, distinct from the people of plains and to counter such descriptions, the elites of kumaun started promoting nationalist aspirations about how kumaun was always a part of larger india and exalting brahminical traditions and marginalising khasa cultural practices in the process (which was particularly emphasised by the colonial sahebs). fast forward to 1990s, the onset of uttarakhand movement, maybe we have to refashion the historical narrative that yeah we are a bit different from the plain dwellers but it's complicated.

i have to find her other articles :))

1 note

·

View note

Text

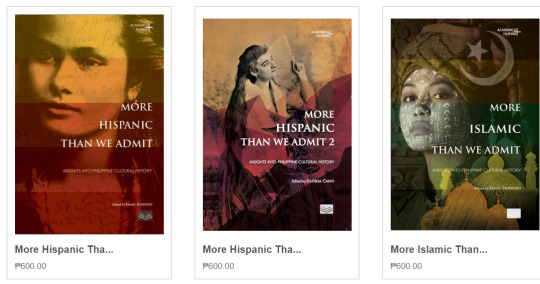

More Hispanic Than We Admit (Volume 1)

Edited by Isaac Donoso

An extended meditation on the encounter between the native and the foreign, this compilation of scholarly essays on Philippine culture and history provokes discussion on the fascinating and sometimes uneasy hybridity that is the Philippines. Spanning an eclectic range of disciplines including anthropology, religion, sociology, philology, literary criticism, historiography, film and art studies, political science, and economics, the compilation traces the manifestations and paradoxes of hybridity by exploring the processes of cultural interaction and transformation.

The book argues that, although subjects of the colonial enterprise, Indios criollos had primacy of agency. The hegemonic cultural discourse invited a counter-discourse that was subtly crafted by emergent Philippine culture.

More Hispanic Than We Admit recuperates our Hispanic past and inspires a continued and lasting engagement with Hispanic Philippine studies.

Published 2008

Hardbound

424 pages

#kalakian#libro#libreriafilipiniana#philippine history#philippines#more hispanic than we admit#Instagram

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peter Turchin on End Times

I have finished listening to End Times: Elites, Counter-Elites, and the Path of Political Disintegration by Peter Turchin. Turchin comes out swinging on the first page asserting that history can be pursued scientifically. The first appendix digs a little more into why he thinks cliodynamics is the answer to the ancient question of whether history can be a science. I find it strange that Turchin cites two fictional examples—cliology from Michael Flynn’s In the Country of the Blind, and Isaac Asimov’s psychohistory—but does not seriously engage with the significant literature in history, historiography, and philosophy of history that explicitly takes up this question.

In any case, Turchin argues that societies pass through integrative periods (marked by income compression) and disintegrative periods (marked by income disparity). Disintegrative periods are largely driven by popular immiseration and elite overproduction, the latter process largely driven by what he calls the “wealth pump,” which sluices most of a society’s wealth to the elites when these elites serve only their own interests exclusively instead of the interests of wider society. Getting the wealth pump under control is one of his policy prescriptions.

At several points in the book I was saying to myself, “But what about…?” and then he took up the objection I had in mind. For example, in his discussion of popular immiseration I was wondering about those who argue that things have never been better, and then he discussed exactly this objection. So, for that, I give him credit. On the other hand, his normie assumptions (he cites the ADL, the SPLC, and the NYT as though they are credible sources) blind him to certain developments in society. For example, he cites some elite financial publications as promoting “market fundamentalism” and discusses how injurious he believes this to be. And not too many years ago this was true, but all of the elite organs of opinion now follow the same ideological line, and it certainly isn’t market fundamentalism. (Are ESG scores and DIE mandates “market fundamentalism”?)

I have run into something like this on several occasions, and I always take the opportunity to throw it back in the face of anyone who utters something they think can be passed off as common knowledge and will not be challenged. The most glaring example of this, as far as I am concerned, is the common claim that the captains of the tech industry are “libertarian.” Again, some years ago this was the case, but now the technology industry is onboard with the same party line ideology as all other institutions. I recently pointed this out in a discussion, when someone brought up this talking point, so I said that the technology industry has produced the most elaborate censorship regime in human history, and my point was acknowledged. Turchin doesn’t make the libertarian tech bro claim, but the claim that elite organs of the financial industry are promoting “market fundamentalism” is comparable.

I have a lot of sympathy for elite theory, and have discussed it (for example, in newsletter 227), but I think it requires some tweaks to get it right. While Turchin does recognize the role of both the one percent (and, he often adds, the 0.10 percent) and the ten percent, which latter largely consists of aspirant elites, I think that elite theory could benefit from a greater focus on these classes and the differences between the two. The relation of the one percent, the true elites, and the ten percent, the aspirant elites, is like that in fiction between vampires and the human beings who serve them. Vampires possess the special power of their undead status, and the human beings who serve vampires have none of these powers, but are promised to gain these powers if they faithfully serve the vampires.

The existence of a class of aspirant elites who feel they are on track to ultimately join the elites, but only if they obey, creates a class of persons who are willing to do anything to please their masters. This is a promise that is held out, but is always vulnerable to being snatched away at any moment, whether by circumstance or by the whim of the vampire elite—as such, the ten percent constitute a different kind of precariat (a power precariant rather than an income precariat). Because of this tantalizing promise, seemingly within reach, but always potentially withdrawn, the aspirant elites who have been allowed into the charmed circle of power, even if they do not yet themselves wield power, may be more vicious and craven than the elites themselves. To take a real world example (not vampires and the supernatural), when dictators like Stalin or Kim Jong-Il hold absolute power of life and death over their subjects, these subjects vie with one another to prove their loyalty. No one wants to be seen as the first to cease clapping, and so the applause goes on and on.

The larger pool of aspirant elites consists both of those who are on track to real elite status, and those who have no realistic hope of “success” so defined. The further into the margin of potential power we trace the aspirant elites, the more desperate they are to prove their loyalty to the elites, and so it is we find that lower-level functionaries are the most brutal and unapologetic in their enforcement of the dictates of the elites; they are hanging on to their potential elite status by a mere thread. These contemptible actions of the aspirant elites in their quest to retain their grasp on potential power serve as a kind of self-hazing and self-blackmail, by which their perspective on the world is irredeemably damaged. They cannot understand that others despise them for the lies they tell, because they can no longer recognize them as lies. The aspirant elites, on the other hand, who have no possibility of ultimately joining the elites, have their perspective sharpened by the bitterness of the denial of their (potential) elite status. They can see all-too-clearly the transformation of their former fellows and take a certain pride in not having engaged in the same craven behavior of the aspirant elites who are confident in ultimately gaining power.

Where this touches on Turchin’s argument is that quite a larger pool of aspirant elites see themselves as viable candidates for elite status than would be apparent from their place on the fringes of the outer party. Turchin discusses the difference between two bumps in the income distribution of lawyers, noting that being a lawyer is not sufficient to be a viable aspirant elite, and that the two groups—viable and non-viable aspirants—are separated by their average income. But I think the important lesson to take away here is that even the lawyers in the lower income bump are not likely to break ranks with the lawyers in the upper income bump (any number of psychological and sociological arguments could be made to show this).

The power of the elites is largely maintained through the threat of what happens to those who break ranks with the elite’s preferred narrative (exemplary justice is meted out to those who break ranks), and this serves to corral all aspirant elites, and not only the viable aspirants. How far down does this extend through society? Morgoth recently wrote that, “The primary function of journalists in the modern West is to tell lies on behalf of Power and hold the weak and powerless to account.” Morgoth humorously compares narrative policing to a superorganism, and says that journalists are the lowest caste of the superorganism. That is how far down it extends. Marxists had a similar niche in their social ecology, which they called the Lumpenproletariat.

1 note

·

View note

Text

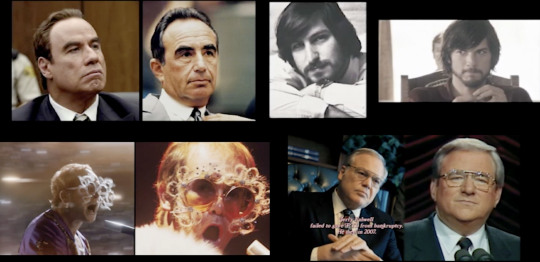

Reality Frictions explores the intersection of fact and fiction on screen

I am extremely happy to report that my feature length documentary/video essay, "Reality Frictions," is finally complete! Huge thanks go to sound designer/mixer, Eric Marin, whose 5.1 mix completely transformed the audio experience of the film for theatrical exhibition.

Although I have been researching this topic and gathering materials on and off for several years, the project went into high gear about a year ago when I posted a call to the scholars and makers associated with the Visible Evidence documentary film community, requesting examples of "documentary intrusions" -- roughly defined as moments when elements from the real world (archival images, real people, inimitable performance, irreversible death, etc.) intrude on fictional or quasi-fictional story worlds.

The response was overwhelming -- in just a few days, I received some 85 suggestions and enthusiastic expressions of support. This community immediately recognized the phenomenon and reinforced many of the examples I had already gathered, while also directing me to dozens more, such as the bizarre and troubling inclusion of Bruce Lee's funeral as a plot device in his final film, Game of Death (1978). For practical reasons, I decided to limit the scope of the project to Hollywood films and their immediate siblings in streaming media & television, but the international community of Visible Evidence noted the erosion or complication of fact/fiction binaries in many non-US contexts as well -- definitely enough for a sequel or parallel project in the future.

As the editing progressed, I quickly realized that the real challenge lay in curating and clarifying the throughline of the project without becoming overwhelmed or distracted by the many possible variations on the fact/fiction theme. The conceptual core of the project was always inspired by Vivian Sobchack's concept of "documentary consciousness," described in her book Carnal Thoughts (2000). Sobchack's inspiration, in turn, derived from a scene in Jean Renoir's film The Rules of the Game (1939) depicting the undeniable, physical deaths of more than a dozen animals as part of the film's critique of the elitism and narcissism of France's pre-war bourgeoisie. Sobchack returned to this scene in two separate chapters of the book for meditations on the ethics and impact of these animal deaths for filmmakers and viewers alike, relating them to both semiotic and phenomenological theories of viewership.

On the advice of filmmakers and scholars who viewed early cuts of the film, nearly all academic jargon has been chiseled out of the narration, leaving what I hope is a more watchable and engaging visual essay that embraces the pleasures and paradoxes found at the intersection of reality and fiction. Additional feedback convinced me to stop trying to make my own VO sound like Encke King, my former classmate who supplies the gravelly, world-weary narration for Thom Andersen's Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003). I've done my best to talk more like myself here, but there's no denying Thom's influence on this project -- both as a former mentor at CalArts and for the strategies of counter-viewing modeled in LAPI. Going back even farther, I would note that it was my work as one of the researchers for Thom's earlier film (made with Noel Burch), Red Hollywood (1996), that got me started thinking about the role of copyright in historiography and the ethical imperative for scholars and media makers to assert fair use rights rather than allowing copyright owners to define what histories may be told with images. This singular insight guided much of my work for the past two decades, realized principally in my ongoing administration of the public media archive Critical Commons (which celebrates its 15th anniversary this month!) as an online resource for the transformative sharing of copyrighted media.

This project also bridges the gap between my first two books, Technologies of History: Visual Media and the Eccentricity of the Past (2011) and Technologies of Vision: The War Between Data and Images (2017). The historiographical focus of this project emerged as an unplanned but retrospectively inescapable artifact of engaging questions of authenticity and artifice, and it afforded the pleasures of revisiting some of my favorite examples, such as Cheryl Dunye's Watermelon Woman (1996) and Alex Cox's Walker (1987), both exemplary for their historiographical eccentricity. An additional, important element of context is the recent emergence and proliferation of generative AI for image synthesis. Technologies of Vision addressed some of the precursors to the current generation of synthetic imaging, which has only accelerated the arms-race between data and images, but recent developments in the field have sharpened the need for improved literacy about the way these systems work -- as well as the kind of agency it is reasonable to attribute to them.

Reality Frictions also aims to intervene in the anxious discourse that has emerged in response to image synthesis, especially among documentarians who feel confidence in photographic and videographic representation slipping away, and journalists besieged by knee-jerk charges of fake news. While I totally understand and am sympathetic to these concerns, challenges to truth-telling in journalism and documentary film hardly began with digital imaging, let alone generative AI. It is axiomatic to this project that viewers have long negotiated the boundaries between images and reality. The skills we have developed at recognizing or confirming the truth or artifice found in all kind of media remain useful when considering synthetic images. Admittedly, we are in a moment of transition and rapid emergence in generative AI, but I stand by this project's call to look to the past for patterns of disruption and resolution when it comes to technologies of vision and the always tenuous truth claim of non-fiction media.

Although the format of this project evolved more or less organically, starting with a personal narrative rooted in childhood revelations about the world improbably drawn from TV of the 1970s, the final structure approaches a comprehensive taxonomy of the ways reality manages to intrude on fictional worlds. Of course the volume and diversity of these instances makes it necessary to select and distill exemplary moments and patterns, all of which provides what I regard as this project's main source of pleasure. One unexpected tangent turned out to be the different ways that side-by-side comparisons trigger uncanny fascination at the boundary between the real and the nearly real. Hopefully without belaboring the point, I aim to parse these strategies from the pleasures of uncanny resemblance to what I view as superficial and mendacious attempts to bolster a flimsy truth claim simply by casting (and costuming, etc.) actors to "look like" the people they are supposed to portray.

Other intersections of fact and fiction are less overt, requiring extra-textual knowledge or the decoding of clues that transform the apparent meaning of a scene. Ultimately, I prefer it when filmmakers respect viewers' ability to deploy existing critical faculties and infer their own meanings. Part of the goal of this project is to heighten viewers' attentiveness to the ways reality purports to be represented on screen; to dissolve overly simplistic binaries, and to suggest the need for skepticism, especially when dramatic flourishes or uplifting endings seem designed to trigger readymade responses. While stories of resilient individuals and obstacles that are overcome conform to Hollywood's obsession with emotional closure and narrative resolution, we should be mindful of the events and people who are excluded by the presumptions underlying these structures.

A realization that develops over the course of the video is that the films with the most consistently complex and deliberate structures for engaging the problematics of representing reality on film come from filmmakers who directly engage systems of power and privilege, especially related to race. From Ava DuVernay's re-writing of Martin Luther King's speeches in Selma (2014), to Ryan Coogler and Spike Lee's inclusions of documentary footage in Fruitvale Station (2013), Malcolm X (1992), and BlacKkKlansman (2018), the stakes are raised for history films with direct implications for continuing injustice in the present. For these makers -- as for the cause of racial justice or the critique of structural power writ large -- the significance of recognizing continuities between the real world and the cinematic one is clear. This is not to argue for a straightforward correspondence between cinema and reality; on the contrary, in the examples noted here, we witness the most complex and controlled entanglements of both past and present; reality and fiction.

In the end, I view Reality Frictions as offering a critical lens on a cinematic and televisual phenomenon that is more common and more complex than one might initially expect. Do I wish the final film were less than an hour long? Yes, and I have no doubt this will dissuade some prospective viewers from investing the time, but once you start heading down this path, there's no turning back and my sincere hope is that I will have made it worth your while.

0 notes

Text

and spreading conspiracy theories)14 wrote anti-Jesuit books as inside revelations of Jesuit hypocrisy. Christian Francken (1549–1603) published Colloquium

Iesuiticum toti orbi Christiano ad recte cognoscendam Iesuitarum religionem utilissimum (The Jesuit conversation that helps the entire Christian world to get

to know well the Jesuit order; Leipzig, 1579) and Profana sectae Jesuiticae vanitas (Profane vanity of the Jesuit sect; Hamburg, 1611) and Elias Hasenmüller

(d.1587) wrote a history of the Jesuit order (Historia jesuitici ordinis), which

was published posthumously in Frankfurt in 1593 by his editor Polykarp Leiser

(1552–1610) who wrote an introduction to it. It defines the goal of the Jesuit

foundation as resistance to heretics, especially the Lutherans.

The publication of the Monita was preceded not only by the appearance of

Western anti-Jesuit literature, which by the end of the sixteenth century had

already shaped the contours of what can be defined as “anti-Jesuitism,” that is

discrimination against or prejudice or hostility toward the Society of Jesus, but

also by the emergence of anti-Jesuitism at the local level. In five decades, or

so, of their presence in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth since 1564, the

Jesuits attracted much animosity, just like in western European countries, from

both Protestants and Catholics,15 from both lay people and clergy, that found

an outlet in copious anti-Jesuit writings. Indeed, the Society of Jesus posed a

threat not just as alleged Counter-Reformation papal troops—usually misrepresented in old-fashioned historiography on the topic, including the otherwise

invaluable contributions of the foremost Polish historians in the field, Henryk

Barycz (1901–94) and Janusz Tazbir (1927–2016)—but also a threat as a cosmopolitan, urban, mobile, versatile, disciplined, and centralized organization

in an era characterized by the emergence of strong local national identities

in several European nation-states that were now—in the aftermath of the

Protestant Reformation—also defined by confessional allegiances.

Earliest Anti-Jesuit Literature in Poland–Lithuania

Tazbir, in his selection of anti-Jesuit literature in Polish translation, identifies

the first anti-Jesuit text already in 1577—just thirteen years after the arrival

of the Society to Poland—as Jakub Niemojewski’s (c.1532–84) Diatribe abo

14 See Andrew McKenzie-McHarg, ”From Status Politics to the Paranoid Style: Richard

Hofstadter and the Pitfalls of Psychologizing History,“ Journal of the History of Ideas 83, no.

3 (2022): 451–75.

15 This is one of the main arguments of Consilium de recuperanda pace, which will be

analyzed below

0 notes

Text

HIS5067 - Lit Review/Discussion Prep #1

This week’s readings center on the central question “what is public history?” As a subdiscipline that conceptually emerged during the nineteenth century – at a critical period in America’s formation of national identity – public history has been entrenched in debates concerning its meaning and relevance for scholars, practitioners, and audiences. As a result, tensions have arisen in attempts to define its parameters, boundaries, and disciplinary challenges. In the following post, I examine the scholarship of Denise Meringolo, Alan Brinkley, and Carl Becker to reflect on the discourse’s history and implications for its present and future.

In Museums, Monuments, and National Parks: Toward a New Genealogy of Public History, Denise Meringolo defines public history as “the employment of historians and historical methods outside of the academy” (Meringolo 2012, xvii). Meringolo establishes a central boundary for public history by situating it outside of academia and establishing its support for collaboration, shared authority, and public value (Meringolo 2012, xxv). Using the development of the National Park Service as a microscopic, yet far reaching, case study, Meringolo argues that “the effort to define public history will be improved by examining its emergence as a multidisciplinary government job” (Meringolo 2012, xxvi). Although the author asserts that the publication is not a historiography of the discipline, the immense detail, primary sources, and historical events referenced provide an effective timeline for understanding public history’s development and role within the U.S. government (especially during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries).

Ultimately, Meringolo argues for a shift in interrogations of public history’s definition in favor of an examination of its relationship to public service (Meringolo 2012, xxii). Within this line of inquiry, the scholarship of Carl Becker and Alan Brinkley are effectively suited to complement Meringolo’s advocacy. Published in 1932, during a critical period just before the official launch of New Deal-funded programs, Becker’s “Everyman His Own Historian” leads with a definition of history, reduced to its lowest terms, as “the memory of things said and done” (Becker 1932, 223). Becker is focused on connecting history with audiences, demonstrating how the discipline is essential to the performance of daily life (Becker 1932, 225). He elucidates the interconnected relationship between history, lived experiences, memory, facts, and interpretation. While Becker acknowledges the limits of both academic historians and “Mr. Everyman” (i.e. the public) as specifically bound to the biases and assumptions of their time, the problematic homogenization of the public as a single person (undoubtedly conceived as white and male) is reflectively limited in its scope. As Meringolo’s research demonstrates, the 1930s was a period wrought with expanding definitions of who constituted America’s increasingly diverse public. African Americans, Indigenous communities, immigrants, and women were all vital to the galvanization of civic and political movements that counter the “one size fits all” narrative of Mr. Everyman.

In “Historians and their Publics,” Alan Brinkley examines the factors that have contributed to the schism between the academy and the public, noting the role of history’s specializations. He argues that the rise of subfields like social history have highlighted the importance of marginalized and underrepresented histories, and as a result, have drawn a critical light on monolithic narratives of the public’s needs and expectations. Brinkley asserts that one solution to the resulting dilemma is “for historians to do a better job articulating first to themselves and then to others, their own convictions about why it is important to speak to the nonacademic world” (Brinkley 1994, 1029). For Brinkley, this articulation is essential to overcoming struggles related to policy, belief, and present action (Brinkley 1994, 1030). Unlike Meringolo’s scholarship, Brinkley prioritizes defining history outside of the academy as a critical step in bridging the perceived gap between theory and practice.

In examining all three publications, I find that the question of audience (specifically who these texts are written for) is an important filter for considering the impact of their respective research efforts. Although the three authors are writing at distinctly separate moments in time and historical discourse, their writings are clearly aimed at fellow academic audiences. Each publication, available online, can only be accessed through university funded accounts, which for twenty-first century audiences severely limits the public participation their research champions. Brinkley argues that “the attempt to understand the past…is not an arcane academic activity” (Brinkley 1994, 1030). As such, history’s relationship to “present action” (Brinkley 1994, 1030) and “living history” (Becker 1932, 227), as well as its professionalization within government (Meringolo 2012, 155) must move beyond the limits of academic “expertise” to earnestly engage in public interpretation and social value.

Bibliography

Becker, Carl. “Everyman His Own Historian.” The American Historical Review 37, no. 2 (1932): 221–36. https://doi.org/10.2307/1838208.

Brinkley, Alan. “Historians and Their Publics.” The Journal of American History 81, no. 3 (1994): 1027–30. https://doi.org/10.2307/2081443.

Meringolo, Denise D. Museums, Monuments, and National Parks: Toward a New Genealogy of Public History. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012.

0 notes

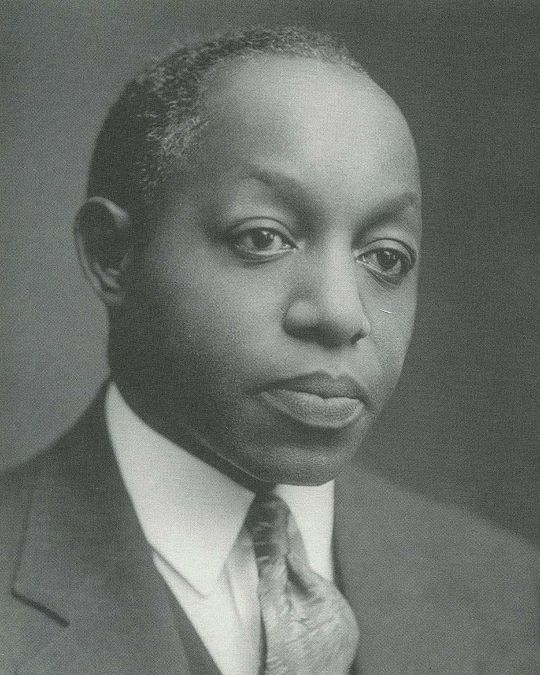

Photo

Alrutheus Ambush Taylor (November 22, 1893 – June 4, 1954) historian, was born in DC. He earned a BA from the University of Michigan and taught at the Tuskegee Institute and the West Virginia Collegiate Institute. Carter G. Woodson brought him back to DC to serve as a research associate with the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. Supported by a grant from the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial Fund, he began researching the role of African Americans in the South during the Reconstruction. He believed that the view of Reconstruction then prevailing in the US was deeply flawed. Though most of the work upon which that view rested had been done at Johns Hopkins University and Columbia University and then published by their respective university presses, he believed that the authors had not lived up to “the requirement of modern historiography” and had instead “written to prove that the Negro is not capable of participation in government and to justify the methods of intimidation instituted to overthrow the reconstruction governments of the Southern commonwealths.” He wrote The Negro in South Carolina During the Reconstruction. The book was first printed in the Journal of Negro History. His book drew upon a host of sources that white writers had neglected, including diaries, letters, church reports, school reports, census materials, agricultural records, economic data, local society proceedings, petitions, African American newspapers, and travel accounts by foreign visitors. He was able to counter the negative stereotypes that dominated previous writing and offer a more balanced account of the African American experience after the Civil War. He followed that book with The Negro in the Reconstruction of Virginia. He became a professor of history at Fisk University, where he remained for the rest of his career. In 1935 he earned a Ph.D. degree from Harvard, and in 1941 he published the third monograph of his Reconstruction trilogy, The Negro in Tennessee, 1865-1880. He was working on a comprehensive history of Fisk, yet another positive legacy of African Americans during the Reconstruction period. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence https://www.instagram.com/p/ClQvIFqrMkE/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

why is black art misrepresented

One may be tempted to question at this point what difference it makes whether Louis Jordan garners acclaim as a “jazz” musician or as a “rhythm and blues” musician, so long as his accomplishments receive credit in some manner.

Ake, David. Jazz Cultures, University of California Press, 2002. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/northeastern-ebooks/detail.action?docID=223039.

Created from northeastern-ebooks on 2022-07-15 14:43:33.

This quote, at first glance, didn’t startle me in any way. The counter argument presented here is superficially okay; we should prioritize crediting deserving artists in any way. After closer reading, however, Louis Jordan being credited in history as a “rhythm and blues” musician is a gross misrepresentation of what his life’s work and legacy in popular music is. Ake raises the question, what kind of credit do black artists deserve?

Historiography (the study of methods used by historians) often reveals black popular music to have been misrepresented by the media, historic records, and later audiences. It is seldom considered art or mainstream culture by past accounts. Reasons why Louis Jordan was not properly credited as a jazz artist are that he was a singer, his music did not match the popular, serious, and virtuostic bebop style of the time, and he did not shy away from the African roots of his music. His legacy was left out of jazz history because it did not fit the theme of his era.

Other examples of black art being miscredited is, in my opinion, ragtime. While virtuostic and revolutionary, musicians and non-musicians often don’t immediately perceive it to be an advanced genre. The elements of ragtime that differentiate it from sonatas or etudes are syncopation, blue notes, and a focus on rhythm. These traits are also distinctly African. Ragtime is not easy to play, and the perception that it is is rooted in white supremacy.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Domenico Losurdo (1941-2018)

Who is he?

Domenico Losurdo was one of the greatest contributors to the development of Marxist theory in the 21st century. Sadly, he passed away in 2018, a staggering loss to the communist international alongside Samir Ain in 2017. His critiques are useful to understanding the vary political and ideological trends of the last century - a thinker I highly recommend. Whether it was critiquing anarchism, liberalism, pacifism, anti-communism, Nietzschian thought & left communism, the anti-Stalin paradigm, he was rewarded with obscurity.

Here’s a list of his books:

https://www.goodreads.com/author/list/638586.Domenico_Losurdo

I highly recommend his Liberalism: a Counter-History. In it, he systemically dismantles the presentation of liberalism as a progressive force. Digging into the ideological foundations & the spatial delimitations of liberalism, he presents liberalism as one of the most pervasive and damaging ideologies that has excused colonialism, eugenics, racism, slavery, etc.

He also did a fantastic historiography/monograph on Stalin. Lulu dot com has a copy and you buy for 14 dollars: https://www.lulu.com/en/us/shop/domenico-losurdo/stalin-history-and-critique-of-a-black-legend/paperback/product-5njw2j.html?page=1&pageSize=4

#marxism#marxism-leninism#marxist#socialism#socialist#theory#bookshelf#book recommendation#book list#domenico losurdo

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every rebellions, plots, conspiracies, and seditions against Henry VII, by chronological order.

1485: Henry VII becomes king after his victory at Bosworth. Two hundred men from the Calais garrison flee to Flanders.

1486: attempted murder against Henry VII at York. The Stafford brothers rebel and take Worcester, while viscount Lovell rebels in Richmondshire. Eventually, the Stafford brothers are captured and one executed, while Lovell flees in Flanders to the court of Margaret of York, dowager duchess of Burgundy.

1487: Lambert Simmel's rebellion. A Yorkist conspiracy proclaims a commoner Lambert Simmel to be the escaped earl of Warwick from the Tower (Edward Plantagenet, nephew of Richard III and Edward IV). He is proclaimed 'Edward V' in Dublin by the Anglo-Irish aristocracy and joined by 2,000 german mercenaries led by viscount Lovell and his cousin John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln. With a mixed german-irish force, Landing in Lancashire enjoyed limited defection in northern England (mainly lord Bolton of Scrope, lord Bolton of Masham, and Sir Thomas Broughton). Their ~8,000 force is beaten at Stoke by a Tudor army led by the king and the earl of Oxford. Death of Lincoln and Lovell, Simmel is spared. Before the rebellion, Henry VII preemptively jails some key Yorkists, including his mother-in-law Elizabeth Woodville and his brother-in-law the Marquess of Dorset.

1489: Anti-tax rebellion in Yorkshire. The rebels led by Sir John Egremont murder the earl of Northumberland and take York before dissolving at the arrival of the royal army. Egremont flees to the court of Margaret of York.

1491: At Cork, a man proclaims that he is Richard of Shrewsbury, the disappeared second son of Edward IV. His true identity remains unknown. ‘Richard’ receives immediate support nonetheless from some Yorkists such as John Taylor, a former supporter of the duke of Clarence (Edward IV's brother).

1492: 'Richard' land in France, where he was welcomed by Charles VIII, who is at war with England. Henry VII retaliate by an invasion from Calais and sign the treaty of Etaples. Charles VIII agreed to stop supporting English rebels and give the Tudor king a pension.

1492: The peace treaty is unpopular in England, and 'Richard' is welcomed in Flanders by Margaret of York and Maximilian of Habsburg, ruler of the Burgundian estates. Maximilian is angered by the separate peace Henry VII made without consulting him. He recognizes him as the rightful king of England. The news of Richard's survival and reappearance began to be known in England and test the allegiance of Henry VII's subjects.

1493: Henry VII retaliate by imposing a blockade on the Netherlands. Counter-measures ensued, leading to an embargo from both parties, which lead to riots in London. 'Richard' assists at Maximilian's coronation as Holy Roman emperor and is promised support for his restoration. Scotland and Denmark recognize his legitimacy.

1494: Maurice Fitzgerald, earl of Desmond, revolts against the Tudors and leads a rebellion in Munster.

1495: an essential group of plotters is arrested. It consists of the king's own Chamberlain and the most powerful knight in England, Sir William Stanley (he was mighty in Cheshire and had £10,000 of reserve in cash at his castle of Holt). Lord Fitzwater (important Calais official and landowner in East-Anglia), Sir Simon Mountford (significant landowner in Warwickshire), William D'Aubeney, Thomas Cressener, Thomas Astwode, and Robert Ratcliff. They were mainly former supporters of Edward IV, and some had connections with duchess Cecily's household. Sir Robert Clifford, one of the plotters, betrayed the entire plot and was pardoned. Others were fined or executed, like Stanley.

'Richard' prepares to invade England by East-Anglia with a force of exiled and Flemish mercenaries. Stormy winds scattered his forces and made him land in Kent, and his force of 300 soldiers is beaten by the Earl of Oxford at his arrival at Deal. He flees and lands with the remainder of his troops in Ireland, where the revolted earl of Desmond joins him. Their combined forces fail to take Waterford. After this defeat, 'Richard' and his supporters arrive in Scotland.

1496: restoration of trade between The Netherlands and England, as Henry VII join the Holy League against France. The earl of Desmond also makes his peace with Henry VII. A Scottish army invades England as 'Richard' promised to give Berwick £50,000 to the Scottish king James IV. Little result ensues except for some small raidings.

1497: 'Richard' marries a cousin of the Scottish king, Catherine Gordon. As the king of Scotland makes a truce with England, he tries to land once again in Ireland with Sir James Ormond's support. However, Ormond's murder led to the failure of the uprising, and 'Richard' flee from Ireland with three ships.

Taxation for the Scottish war led to the Cornish rising. A blacksmith, Michael Joseph, leads the revolt with lord Audley and brings many gentrymen from Cornwall to rebellion. The rebellion extends to neighboring counties as the rebel take Exeter and march to London, virtually unopposed. A 25,000 royal army face some ~15,000 rebels at Blackheath, near London, and triumph. Once again, the earl of Oxford's vanguard is instrumental for the victory against the rebel.

'Richard' finally land in Cornwall, hoping to bolster his support with the Cornish's discontent. An uprising in his favor occurs (second Cornish rebellion), and his 8,000 men fail to take Exeter. His attempted fleeing after the encirclement of his forces by the Tudors led to his capture at Bealieu abbey.

'Richard' confess he is an impostor and a Flemish by the name of Perkin Warbeck. He and his wife are welcomed at court.

1498: 'Richard' tries to escape court and is captured and jailed in the Tower of London.

1499: A Cambridge scholar by the name of Ralph Wiford dreamt that he would become king if he claimed he was the earl of Warwick. His uprising in East Anglia failed, and he is executed.

Edmund de la Pole, earl of Suffolk and brother of the Earl of Lincoln (thus nephew of Richard III), leave England for Flanders after killing a commoner in London before agreeing to come back.

The French hand over many supporters of 'Richard' in France, including John Taylor. Many are executed, but Taylor's life is spared.

An attempted escape made by 'Richard' and his cousin Edward, earl of Warwick, fail, and they are both executed.

1500-1503: Henry VII lost his wife in childbirth and two sons (Arthur and Edmund). Dynastic fragility ensue as Henry VII have only one surviving male heir.

1501: Edmond de la Pole and his brother Richard flee for the Flanders. Henry VII promptly jail their brother, William, with Sir James Tyrell and Lor William Courtenay. Royal officials are sent in East Anglia to monitor the de la Pole affinity. Sir James Tyrell 'confess' before his death the murder of the Princes in the Tower for Richard III.

1504: 'treasonous' talks between Calais officials. They argue about who would be the successor for a declining Henry VII and hesitate between the duke of Buckingham and the Earl of Suffolk, omitting Henry VII's children.

1506: The Habsburgs deliver Edmund de la Pole to Henry VII, who jail him at the Tower of London. In exchange, Henry VII loan them immense sums of cash, such as £108,000 in April.

1509: Henry VII dies, leaving the crown to his adult heir, Henry VIII.

I might have missed some small, aborted plot, but there it is.

With this chronology, it's evident that the War of the Roses (or, more accurately, the war of the succession crisis of 1483) didn't end at Bosworth. Henry VII could have been overthrown in 1487 or the late 1490s. There is also a clear distinction between the rebellions of the 1480s and those of the 1490s. The plot following HenryVII's advent is mainly coming from RichardIII's basis of power. It's his men (Lincoln, Lovell, many northerners), his bases of support (the North and Ireland) who try to overthrow the first Tudor.

The plots of ''Perkin Warbeck'' known in historiography, were perilous for Henry VII. Most of his dynastical legitimacy comes from his marriage to Elizabeth of York. A true surviving son of Edward IV would nullify this and put into question the support of every former servant of the late Yorkist king. Hence, Henry VII tried to depict 'Richard' as an impostor and to demonstrate that the Princes of the Tower were dead. Still, he couldn't convince everyone and had to resort to force and the systematic use of a spy network.

Some of those plots might have been exaggerated. The 1504 Calais plot was undoubtedly not a carefully crafted conspiracy but more a manifestation of Henry VII's difficult succession. This chronology also doesn't show the dubious role that many magnates had during this period of unrest. The loyalty of Lord Abergavenny (dominant in Kent) was put into question, as was one of the earls of Derby in the 1490s and Lord Daubeney. Henry VII didn't have many magnates on whom he could truly count.

As you can see, Henry VII was never wholly free from dynastic uncertainty. At his death, Richard de la Pole was still free to push his claim if his brother Edmund died. Henry VIII himself was very wary of potential claimants toppling him. His execution of Edmund de la Pole in 1513 and the duke of Buckingham in 1521 are the best manifestations of this insecurity.

#henry vii of england#war of the roses#tudor era#Perkin Warbeck is named 'Richard'#we don't have definite proof of his identity#richard iii

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Listening to a podcast and I think the most maximally aggravating and contrarian position on American historiography is “The American Revolution was good and righteous and something to be proud of, but the Constitution represented a counter-revolutionary coup against its democratic elements on behalf of speculators and land-owning elites.” Think I might adopt it next time that discourse flares up.

30 notes

·

View notes