#days gone by

Text

Sheet Music 1919 by Irving Berlin

#year: 1919#circa 1919#1910s#decade: 1910s#irving berlin#vintage sheet music#old sheet music#sheet music cover#sheet music#sheet music art#vintage music#yesterdays#the past#memory lane#days gone by

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Days Gone By

The abandoned Beatrice H. Wood School in Plainville, Massachusetts.

📸 flickr

#flickr#original#original post#original photography#original photography on tumblr#tumblr#artists on tumblr#school#building#abandoned#abandoned buildings#abandoned school#decay#urban decay#broken#days gone by#blueiscoool#blueiskewl

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Final Chapter of

📚Days Gone By📚

is now on ao3 and Wattpad

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

At last the ball was over ...

#photographers on tumblr#original photography on tumblr#naturephotography#nature#decay#dead leaves#feather#leaf mold#leaf pattern#sycamore seed#debris#chandelier#rust#water#naturecore#days gone by#the ball was over

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Your chariot awaits. Mounted photo of a man in horse and carriage by J.F. Sweeney Grafton, Mass.

On Etsy: www.etsy.com/listing/1482156318/

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Love for Central Asian Literature Part 1 – Abdurauf Fitrat, Abdulla Qodiry, and Cho’lpon

I’m currently working on a script for my history podcast, the Art of Asymmetrical Warfare, about three Central Asian literary giants: Abdurauf Fitrat, Abdulla Qodiry, and Abdulhamid Sulayman o’g’li Yusunov also known as Cho’lpon and it got me thinking about their influence on my historical interests, reading tastes, and writing style.

If you’re wondering why a podcast about asymmetrical warfare is talking about three Central Asian writers, you should check out my upcoming podcast episode. 😉

How I Became Interested in Central Asian Literature

My interest in Central Asia has been a long time percolating and it was just waiting for the right combination of sparks to turn it into a hyperfixation (sort of like my interest in the IRA). I went to the Virginia Military Institute for undergrad and majored in International Relations with a minor in National Security and my focus was on terrorism. So, I knew a lot about Afghanistan and Pakistan and the “classic” “terrorists” like the IRA, the FLN, Hamas, etc. and I knew of the five Central Asian states (one of my professors was banned for life from either Turkmenistan or Tajikistan and sort of life goals, but also please don’t ban me haha), but my brain bookmarked it, and I went on my merry way.

Then I went to University of Chicago for my masters, and I took my favorite class: Crime, the State, and Terrorism which focused on moments when crime, government, and terrorism intersect. This brought me back to Pakistan and Afghanistan, but this time focusing on the drug trade which led me to Uzbekistan and Tajikistan and their ties to the Taliban and it was sort of like an awakening. I suddenly had five post-Soviet states (if you know me, you’ll know I’m fascinated by post-Soviet states) with connections to the drug trade (another interest of mine) and influenced by Persian and Turkic identities. I was also writing a scifi series at the time that included a team of Russian, Eastern European, and Central Asian scientists and officers, so the interest came at the right time to hook my brain. Actually, if you buy my friend’s EzraArndtWrites upcoming “My Say in the Matter” anthology, you’ll read a short story featuring Ruslan, my bisexual, Sunni Muslim, Uzbek doctor who was inspired by my sudden interest in Central Asia.

Hamid Ismailov’s the Devils’ Dance

I wanted to know more beyond the drug trade and usually when I try to learn about a place whether it be Poland, Ireland, or Uzbekistan, I go to their music and literature. This led me to one of my all-time favorite writers Hamid Ismailov and my favorite publishers Tilted Axis Press.

Tilted Axis Press is a British publisher who specializes in publishing works by mainly Asian, although not only Asian writers, translated into English. They publish about six books a year and you can purchase their yearly bundle which guarantees you’ll get all six books plus whatever else they publish throughout the year. I’ve purchased the bundle two years in a row, and I haven’t regretted it. The literature and writers you’re introduced to are amazing and you probably won’t normally have found unless you were looking specifically for these types of books.

Hamid Ismailov is an Uzbek writer who was banished from Uzbekistan for “overly democratic tendencies”. He wrote for BBC for years and published several books in Russian and Uzbek. A good number of his books have been translated into English and can be found either through Tilted Axis or any other bookstore/bookseller. Some of my favorites include Dead Lake, the Manaschi, the Underground, and the book that inspired everything the Devils’ Dance.

Tilted Axis’ translation of The Devils’ Dance came out the same year I was working on my masters, and I bought it because it is a fictional account of Abdulla Qodiriy’s last days while in a Soviet prison. He goes through several interrogations and runs into his fellow writers and friends: Fitrat and Cho’lpon. Qodiriy is written as detached from events while Cho’lpon comes across as very sarcastic, as if this is all a game, and Fitrat is interestingly resigned to the Soviet’s games but seems to have some fight in him. Qodiry distracts himself from the horrors around him by thinking about his unwritten novel (which he really was working on when he was arrested by the NVKD). His novel focuses on Oyxon, a young woman forced to marry three khans during the Great Game. His daydreaming takes a power of its own and he occasionally slips back to talk with historical figures such as Charles Stoddart and Arthur Connolly-two British officers who were murdered by the Khan of Bukhara (not a 100% convinced they didn’t have it coming).

We spend half of the narrative with Qodiriy and the other half with Oyxon as she is taken from her home and thrown into the royal court of Kokand’s khans where she is raped and mistreated and has to survive the uncertain times of Central Asia during the Great Game. She is passed from Umar, the father, to Madali, the son, to the conquering Khan of Bukhara, Nasrullah who eventually murders her and her children. From a historical perspective, I have a lot of questions about Nasrullah because a lot of sources write him off as a cruel tyrant and nothing more which usually means there’s more…Before Oyxon and Qodiriy are taken to their deaths, there is a poignant scene where the two timelines merge into one that will stay with you long after the novel is over.

The book is a masterpiece exploring themes of colonialism, liberty, powerlessness in face of overwhelming might, the power of the human mind and spirit, the endurance of ideas, even when burned and “lost”, as well as being a powerful historical fiction about two disruptive periods in Central Asian history. It’s also a love letter to the three literary giants of Uzbek fiction: Abdurauf Fitrat: a statesmen who crafted the Turkic identity of Uzbekistan, a playwright and statesmen, Abdulla Qodiriy who created the first Uzbek novel (O’tgan Kunar which was recently translated by Mark Reese and can be bought in most bookstores), and Cho’lpon who created modern Uzbek poetry (you can buy his only novel Night translated by Christopher Fort and a collection of his poems 12 Ghazals by Alisher Navoiy and 14 Poems by Abdulhamid Cho’lpon translated by Andrew Staniland, Aidakhon Bumatova, and Avazkhon Khaydarov in any bookstore).

City of Kokand circa 1840-1888, thanks to Wikicommons

All three men were Jadids (modern Muslim reformers) who worked with the Bolsheviks to stabilize Central Asia, helped create the borders of the five modern Central Asian states, and were murdered by the Soviets during Stalin’s Great Purge of the 1930s. It was illegal to publish their work until the glasnost. Check out my history podcast to learn more about the Jadids and the Russian and Central Asian Civil Wars.

From a literary perspective however, Ismailov wrote the Devils’ Dance similarly to Qodiriy’s own O’tgan Kunlar and Cho’lpon’s Night (whereas Ismailov’s other books: Dead Lake and the Underground are more Soviet era Central Asian literature and his newest book the Manaschi is more post-Soviet). Like Qodiriy and Cho’lpon, Ismailov writes about MCs who are not the master of his own fate, but instead are going through the motions of a fate already written, one of his MCs is a woman unfairly caught in a misogynistic system that uses women as it sees fit (although I would argue that Hamid gives his women characters more agency than either Qodiry and Cho’lpon), and he writes about the corruption and inefficiencies of whatever government agency is in control at the time – whether it be a Russian, a Khan, or an indigenous agent of said government. All three books end in death, although only Cho’lpon’s Night and Ismailov’s the Devils’ Dance end in a farce of a trial. Even stylistically Ismailov mimics the rich and dense language of Qodiriy whereas I find Cho’lpon’s style crisper although no less rich for it.

Abdurauf Fitrat’s Downfall of Shaytan

While Ismailov led me down a historical rabbit hole which is captured on my history podcast, I also wanted to see if any of Fitrat’s, Qodiry’s, or Cho’lpon’s work had been translated into English.

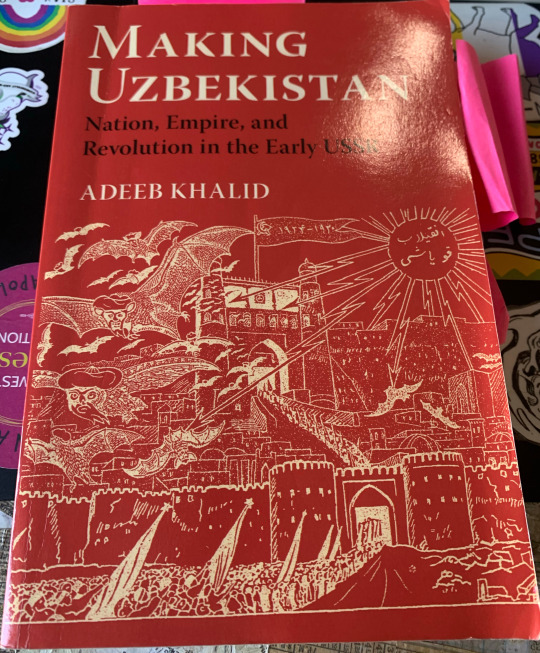

So far, I can’t find anything by Fitrat except excerpts in the Devils’ Dance and Making Uzbekistan by Adeeb Khalid (one of my all-time favorite history books by one of my favorite scholars who also happens to be very kind and patience and I still can’t believe I interviewed him for my podcast).

Fitrat wrote a specific play I really want to read called Shaytonning Tangriga Isyoni which Dr. Khalid translated as Shaytan’s Revolt Against God. According to the summary provided by Dr. Khalid it is a challenging take on the Islamic version of Satan’s downfall.

According to Dr. Khalid, in Islamic cosmology God created angels from light and jinns from fire and they could only worship God. When God made Adam, He commanded all angels and jinn to bow before him. Azazel (who would become Shaytan) refused claiming he was better than Adam who was made out of clay. He was cast out of heaven and became Shaytan/Iblis.

Fitrat reimagines Shaytan’s defiance as heroic. He is disgusted by the angels’ submissive nature and God’s ability to create anything and yet he chooses to create servants. Azazel has seen God’s plan to create another being out of clay and have the angels worship him as well, which Azazel sees as a betrayal on God’s part. Gabriel, Michael, and Azrael try to convince Azazel to see reason and instead he brings his grievance to the other angels who are confused. God intervenes and the angels give in, but Azazel continues to defy God. God strips him of his angelic nature, and he turns into Shaytan who warns Adam of God’s treacherous nature and vows to free him and all other creatures from God’s trickery.

Doesn’t it sound amazing?! Fitrat has outdone Milton in terms of completely overturning God’s and Satan/Shaytan’s rules (also no wonder he was marked for execution right? Complete firebrand and pain in the ass (and I mean that with love)) and I really want to read it. So, either someone needs to translate this into English, or I need to learn Persian/Uzbek, which ever happens first, haha (judging on how my Russian is going…)

Abdulla Qodiry’s O’tgan Kunlar

While I can’t find any of Fitrat’s work in English, there have been two translations of Abdulla Qodiriy’s novel and the first ever Uzbek novel O’tgan Kunlar. In English, the title translates as Days Gone By or Bygone Days. There are two translates out there: Days Gone By translated by Carol Ermakova, which is the version I’ve read, and Otgun Kunlar by Mark Reese, which I haven’t read yet but I’ve heard him speak (and actually spoke to him about his translation – thank you Oxus Society) so you can’t go wrong with either one.

O’tgan Kunlar is an epic novel set in the Kokand Khanate in the 18th century and is about Otabek and his love Kumush. There’s also a corrupt official, Hamid who hates Otabek because Otabek is a former who wants to change the society Hamid benefits from. Hamid tries to get Otabek killed for treason because of his reformist believes, but the overthrow of the corrupt leader of Tashkent (who Otabek worked for) saves Otabek’s life. However, the corrupt leader’s machinations convince the Khan to declare war against the Kipchaks people, who are massacred. Otabek and his father vehemently disagree with the massacre of the Kipchaks.

Once Otabek is released and gets revenge against Hamid, he marries Kumush without his parent’s approval and is torn between the two families. His mother hates Kumush and forces him to take a second wife, Zainab. Obviously, things go terribly wrong as Otabek doesn’t even like Zainab and Kumush doesn’t know how to feel about her husband having a second wife. Zainab hates her position within the household and eventually poisons Kumush.

Abdulla Qodiriy thanks to Wikicommons

O’tgan Kunlar is considered to be an Uzbek masterpiece that is central to understanding Uzbekistan. Not only is it a great tragic love story, but it also highlights some of the things Qodiriy was thinking about as he engaged with other Jadids. Just as Otabek argued for reforms especially in the educational, social, and familial realms, the Jadids were making the same arguments. We can also see the Jadid’s struggle with the ulama and the merchants in Otabek’s struggle with Hamid. Qodiry attempts to capture the struggle women went through by writing about the horrors for arrange marriages and polygamy, but Kumush is an idealized version of a woman. She is the pure “virgin” like Margarete from Faust while the other two female characters; Otabek’s mother and Zainab are twisted, bitter woman who hurt those they “love”. One could argue they’ve been corrupted by the society they live in, but they also lack the depth of Otabek and even his father.

One of the most interesting parts of the novel is the massacre of the Kipchaks because it is written as the horror it was and both Otabek and his father condemn the action. His father even claims that there is no sense if hating a whole race for aren’t we all human? Central Asia is a vast land full of different peoples who share common, but divergent histories and while these differences have led to massacres, there have also been moments of living peacefully together. It’s interesting that Qodiriy would pick up that thread and make it a major part of his novel because this was written during the Russian Civil Wars and the attempts to create modern states in Central Asia. The Bolsheviks really pushed the indigenous people of Central Asia to create ethnic and racial identities they could then use to better manage the region and so one wonders if Qodiriy is responding to this idea of dividing the region instead of uniting it.

Cho’lpon’s Night

While O’tgan Kunlar is a beautiful book and Qodiriy is a masterful writer, I prefer Cho’lpon’s Night (although don’t tell anyone). Night was supposed to be a duology, but Cho’lpon was murdered before he could finish the second book. Cho’lpon wrote Night in 1934, after years of being attacked as a nationalist. It was a seemingly earnest attempt to get into the Soviet’s good graces. Instead, he would be murdered along with Qodiriy and Fitrat in 1938.

Night is about Zebi, a young woman, who is forced to marry the Russian affiliated colonial official Akbarali mingboshi. The marriage is arranged by Miryoqub, Akbarali’s retainer. Akbarali already has three wives and, like in O’tgan Kunlar, adding a new wife causes lots of problems in the household. Meanwhile Miryoqub falls in love with a Russian prostitute named Maria and they plan to flee together. While they are fleeing they met a Jadid named Sharafuddin Xo’Jaev and Miryoqub becomes a Jadids. Meanwhile Akbarali’s wives conspire against Zebi and attempt to poison her but she unwittingly gives it to Akbarali instead. Zebi is arrested and found guilty of murdering her husband and sentenced to exile in Siberia. The book ends with Zebi’s father, who encouraged her marriage to Akbarali, is driven made by his daughters fate and murders a sufi master while Zebi’s mother goes mad, wandering the streets and singing about her daughter.

Like Qodiriy, Cho’lpon is interested in examining governmental corruption, the need for reform, and women’s plight, but Cho’lpon is less resolute than Qodiriy. Cho’lpon’s novel is constructed similar to poetry: an indirect attempt to capture something that is concrete only for a moment.

His characters are own irresolute or ignorant of important pieces of information meaning they are never truly in full control of their fates. Even Miryoqub’s conversion to Jadidism is to be understood as a step in his self-discovery. In Cho’lpon’s world, no one is ever truly done discovering aspects of themselves and no one will ever have true knowledge to avoid tragedy.

Cho'lpon courtesy of Wikicommons

It is interesting to read Night as Cho’lpon’s own insecurity and anxiety about his own fate and the fate of his fellow countrymen as Stalin seemingly paused persecuting those who displeased him. While Qodiriy crafted and wrote O’tgan Kunlar in the 1920s, which were unstable because of civil war, but promised something greater as the Jadids and Bolsheviks regained control over the region, Cho’lpon wrote Night during the height of Stalin’s Great Terror, most likely knowing he would be arrested and executed soon.

Both novels are beautifully written historical novels about a beautiful region, but I prefer Cho’lpon’s poetic prose and uncertainty.

Conclusion

Reading the works of Fitrat, Qodiriy, and Cho'lpon not only introduced me to a history I knew little about, but also introduced me to a whole literature I never knew existed. The books mentioned in this blog post are beautiful pieces literature and will challenge how you see the world and how much literature we miss out on when we don't read beyond authors who work in our native tongues.

The canon of Central Asian literature is immense, with only a handful of books and poems translated into English. I hope more works are translated so other people can engage with these books and poems and learn about these writers and the circumstances that shaped them. And, if you haven't, go check out Tilted Axis who are doing amazing work translating books so people can engage with them.

If you're enjoying this blog, please join my patreon or donate to my ko-fi

#central asian history#central asian literature#abdurauf fitrat#abdulla qodiriy#cho'lpon#O'tgan Kunlar#Days Gone by#Night#Hamid Ismailov#the Devils' Dance#Soviet Union#Soviet Central Asia#Uzbekistan

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

#found photo#vintage photo#old photo#as they were#vintage lady#vintage snapshot#argyle socks#yesterdays#vintage style#the past#memory lane#days gone by

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

Days gone by...............................B & C

1 note

·

View note

Text

Behind the Door

The former giant At&T building, which stood empty for decades, at the F. Gilbert Hills State Forest in Foxboro, Massachusetts.

📸 flickr

#flickr#original#original post#original photography#original photography on tumblr#tumblr#artists on tumblr#building#abandoned#abandoned buildings#concrete building#decay#urban decay#broken#behind the door#days gone by#blueiscoool#blueiskewl

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 8 of

📚Days Gone By📚

Is now on ao3 and WattPad

#days gone by#ww2 au#bridgerton#benophie#benophie au#benedict bridgerton#sophie beckett#benedict x sophie

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

#poll#polls#kpop#day and night#265247#stop#deep in love#not mine#i wait#i need somebody#love me or leave me#landed#days gone by#day6

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Should have been a breakfast add!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

@manifoldmischief

When she was summoned to the throne room Sif had a feeling the game was up. She’d pushed too far.

It had all made sense at first, changes in Odin’s behavior given the death of his wife and son with Thor gone afield on quests. Then her missions had mounted, always solo ones, always keeping her so busy, and it nagged at her. Sif had started paying closer attention to their conversations, and her suspicions felt confirmed - something was wrong with Odin. He was just different enough for her to tell, but after all she had grown up running through the palace with Thor and Loki. She didn’t know what it meant, maybe it truly was only grief, but she kept sharp eyes on him from there.

Then she’d started probing. Subterfuge had always been Loki’s specialty, but Sif applied her own skills and maneuvered conversations to glean information about his state. It wasn’t adding up. Something felt off, but in a familiar sort of way, and she didn’t know what to make of it.

It finally clicked into place after a particularly irksome conversation. Walking out of the throne room it occurred to her there was only person who’d ever been able to frustrate her that much, and it was his dark haired son.

It was a mad idea.

So she held onto it. Listened more. Tested him. Loki was a brilliant liar, but lies didn’t work when one party knew the truth. He had failed enough of the tests that she felt sure of her idea, but as two guards waited for her to acquiesce to the summons, Sif suspected that she had not been subtle enough in her prodding.

She stowed her sword on her back, and was glad that wouldn’t look suspicious. “Shall we?” she nodded to her escort and they fell into step with her. No more sound fell from her lips as they walked.

She was resolved firm as the doors to the throne room were opened for her, and she strode forward confidently. “My King,” Sif bowed, and the respect did not reach her face. “You summoned me?”

#manifoldmischief#days gone by#[ tell me if you'd like anything changed. this got long do NOT feel like you have to match lol ]

18 notes

·

View notes