#dopefiend

Text

pure bliss straight from hell🖤

#girls who like drugs#drug aesthetic#drug#slamming drugs#drugs#iv drugs#girls who do drugs#noddsquad#drug addiction#dopefiend#opiate addiction#heroin addiction#heroin asthetic#heroin junkie#heroin#black tar heroin#junkie#addict#addiction#noddinoff#nodsqaud#noddin out#nodding#opiate withdrawal#opiates#opiaddict

113 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Haha Best Caption Wins! What a gem!! • ¥ • ¥ • ¥ • ¥ •#skuttlebutt #dopefiend #dopefeindlean #tweaking #tweakergirl #noddin #noddingoff #explorepage #fyp #drugsarebadmkay #crackhead # (at Caroline County, Maryland) https://www.instagram.com/p/CeIIJRju1nN/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#skuttlebutt#dopefiend#dopefeindlean#tweaking#tweakergirl#noddin#noddingoff#explorepage#fyp#drugsarebadmkay#crackhead

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Symbolic Violence of Public Health Outreach

Abscesses are merely the tip of the iceberg of the crisis facing health care for the homeless in the United States. Most patients with abscesses are also infected with hepatitis C, smoke cigarettes, drink large quantities of alcohol, and eat poorly. Consequently, they are at risk for a panoply of chronic conditions as they age, including malnutrition, liver disease, emphysema, tuberculosis, depression and dementia, not to mention gunshot and knife wounds.

Injection drug users constituted one of the epicenters of the outbreak of HIV in the industrialized world during the 1980s. Epidemiologists identified injectors as a potential vector for spreading HIV into heterosexual populations, and this threat raised the stakes of inadequate health care for the indigent. A worldwide public health movement known as “harm reduction” emerged, modeled on earlier hepatitis A prevention initiatives for heroin injectors in Holland. The movement advocated nonjudgmental engagement with active drug users and hoped to lower the cultural and institutional barriers to medical services. Harm reduction outreach initiatives such as needle exchanges were not predicated on abstinence; they were designed to be pragmatic and inclusive.

Despite the radical, user-friendly intentions of harm reduction activists, their movement could not escape what Foucauldian critics refer to as the “logic of governmentality.” Harm reduction operates within the limits of a middle-class public health discourse committed to educating “rational clints…free to choose health). In pursuit of knowledge and progress, medicalized discourses promote disciplined subjectivities that self-impose responsible behavior. In short, harm reduction became the gentle strand in the disciplinary web that seeks to rehabilitate the lumpen. The cross-class effects of this form of "positive” biopower, however, are often contradictory.

Knowledge may be empowering to the middle class, but prevention and outreach messages that target the decision making processes of drug users fail to address the constraints on choice that shape need, desire, and personal priorities among the indigent. Arguably, many of the outreach programs designed to empower vulnerable injectors and to treat them as rational actors shame them as much as, or more than, they help them. Hypersanitary messages clash with the realities of practical survival on the street. Medical social services predicated on “empowering individuals” to make “informed choices” misrecognize the power relations that constrain socially vulnerable populations and that shape subjectivities.

For example, healthcare providers and outreach workers routinely advised the Edgewater homeless never to share injection paraphernalia (syringes, cookers, cottons, and rinse water). For the first dozen years of the HIV epidemic, injectors throughout the United States were given little bottles of bleach to clean their paraphernalia. But it is impossible to rinse a used cotton or cooker with bleach if one is trying to inject leftover residues of heroin. Furthermore, in the moral economy on the street, sharing the same cooker is both ethical and pragmatic. From the perspective of the street-based injector, sharing injection paraphernalia, especially the anchillary components such as cookers, cottons, and water, promotes health rather than damages it. The injection practices defined as sanitary by biomedicine were a luxury most street-based injectors could not afford. Even though all of the Edgewater homeless had technical knowledge of the way blood-borne infections are spread, they would often flamboyantly squirt several units of heroin from their used syringe into one another’s cookers as a “favor.” Their top priority was to avoid dopesickness, and that required them to share publicly and frequently in order to build a generous reputation.

Early in our project, Philippe naively asked Frank whether he shared needles. It immediately became apparent the standard public health messages we considered ethically important to promote were inadvertently offensive.

Frank: Oh, c'mon, man! Don’t ask me that question. You know damn well I share needles. It happens to everybody a million times.

We always try not to share needles but we still do it. Hey, if you’re sick, you’re not gonna worry about it. When you gotta fix, you gotta fix.

People gonna share a needle; they’re gonna share a cooker, they’re gonna share whatever the fuck they got to if they’re sick.

I mean, we worry about AIDS, but when you’re sick on dope and you got to fuckin’ get well you not gonna worry about that shit right at the moment.

That’s the way it is. I’m sorry, man. [handing Hogan the needle he had just used]

Hogan: [holding up the needle] Give any motherfucker out here a motherfuckin’ taste of forty units of dope and even if the man has any kind of knowledge about AIDS, he ain’t gonna give a fuck. If he’s sick, he’s gonna fix.

I’m Sorry, but that’s the gospel motherfuckin’ truth.

Philippe: But… but shouldn’t you at least rinse that needle with bleach before giving it to Hogan?

Frank: Shut up Philippe! I know you’re in the AIDS business and all, but water works. I know water works; I’ve been rinsing with water for years. We all have. None of us have HIV. Water works. I know it. Trust me. We only share with people we know.

When we recorded this particular conversation, we thought that the Edgewater homeless were in denial about their objective level of HIV risk. A close reexamination of large-scale epidemiological HIV infection patterns, however, suggests that Frank was probably right about his simple HIV prevention strategy of “rinsing with water.” None of the Edgewater homeless contracted HIV during the twelve years we spent with them, and they were not anomalies. Laboratory and epidemiological studies have consistently documented that water effectively flushes the HIV virus out of contaminated needles.

Furthermore, epidemiological infection patterns from the 1990s and 2000s also suggest that ancillary paraphernalia sharing is probably not responsible for transmitting HIV in the United States. Most likely, in order for enough blood-to-blood contact to occur and to transmit HIV, one would have to reuse a syringe that has not been rinsed with anything. In the United States, HIV rates were two to three times higher in East Coast cities than in West Coast cities throughout the 1990s. This is because Mexican black tar heroin was the only form available on streets west of the Mississippi River during the 1980s through the 2000s, and its gooey consistency forced injectors to rinse their syringes with water in order to prevent the plungers from jamming. In contrast, the heroin used east of the Mississippi during these same years care primarily from Southeast Asia and later from Colombia. It was in a highly soluble white powder form that did not clog needles. Injectors in eastern states, consequently, did not need to rinse their needles with water on a routine basis in order to reuse them.

Most of the Edgewater homeless regularly volunteered to be research subjects for large public health epidemiological surveys in order to obtain the ten- to twenty-dollar incentive fees paid by these projects. They were required to attend a counseling session on HIV risk before receiving the money. These sessions provided them with enough detailed information to learn that their daily injection practices were self-destructive, but there was relatively little they could do to change their behavior because they lived on the street and were physically addicted to heroin. Most of them were already taking the basic precaution of avoiding direct needle sharing whenever possible. Direct needle sharing between running partners, however, was so routine that they usually did not remember to report it as “using someone else’s syringe” when they completed the questionnaires of our epidemiological collaborators.

Hepatitis C prevention campaigns highlight the counterproductive effect of imparting impractical scientific knowledge without also offering resources and structural alternatives. More subtly, the data on hepatitis C prevention suggests that the public health field of drug research and harm reduction outreach suffers from a hypersanitary bias. Halfway through our fieldwork, public health researchers began using a new technology to test the blood of street injectors for the hepatitis virus (HCV), dubbed the “silent killer” by the media and some researchers. All of the Edgewater homeless discovered, to their dismay, that they were infected with hepatitis C. Unfortunately counselors and doctors had little practical advice to give infected injectors, because the pathophysiology of the virus was poorly understood by scientists. The prevailing statistics at the time indicated that some people fell sick and died of liver disease rapidly; most, however, suffered from no HCV-related liver problems, even when they continued to drink alcohol and almost 10 percent spontaneously cleared the virus from their blood with no treatment. Interferon, the medication used in the 2000s to treat hepatitis C infection, has uncomfortable side effects and works for only 50 percent of those who manage to complete a full year of the difficult daily regimen. Moreover, the official U.S. federal guidelines for treating liver disease recommended sex months of abstinence from alcohol or drug use prior to initiating therapy.

Public health researchers conscientiously educated the Edgewater homeless about the blood-sharing acts that had infected them, but injectors could do little with that knowledge. At the end of their counseling sessions, they were given a card with a toll-free number and ushered out the door back onto the street, where they usually felt compelled to pool the “incentive fees” they had just received for being research subjects to buy heroin and engage in risky injection practices. Combining Bourdieu’s critique of symbolic violence with Foucault’s insight on the knowledge/power nexus suggests that the harm reduction movement’s well-intentioned hepatitis C blood-testing and counseling initiative inadvertently created a dynamic of unproductive self-blame among the Edgewater homeless, which contributed to the convention misrecognition of the relationship between power and individual self-control. No resources were provided to injectors with HCV. Instead they received a slew of detailed technical information about the micro injection practices through which they had infected themselves. This kind of knowledge-based intervention reflects the historical turn public health has taken under neoliberalism. Rather than investing in structural interventions to protect the health of its citizens, the state frames health as the individual’s moral responsibility to choose a lifestyle that avoids risk.

The Edgewater homeless did not analyze their personal problems in terms of Foucault’s biopower and governmentality, or Bourdieu’s symbolic violence and misrecognition. On the contrary, they appreciated the respectful treatment they received when they participated as research subjects in public health projects (including ours). Even though they could not change their risky injection practices following the testing, they often felt that they had done something responsible merely by getting tested. Blood testing for HCV and HIV, consequently, engendered a false sense of confidence. Soon, most of the Edgewater homeless came to accept HCV infection as a normal condition. The hepatitis C prevention campaigns of the early 2000s illustrate how the uneven effects of biopower on lumpen populations often backfire. Polite counselors taught long-term street-based addicts to take personal responsibility for damaging their bodies. This interaction reaffirmed the “hope-to-die-with-my-boots-on” righteous dopefiend subjectivity among the Edgewater homeless. Being willfully and oppositionally self-destructive feels like an empowering alternative to conceiving of oneself as a sick failure who lacks self-control.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

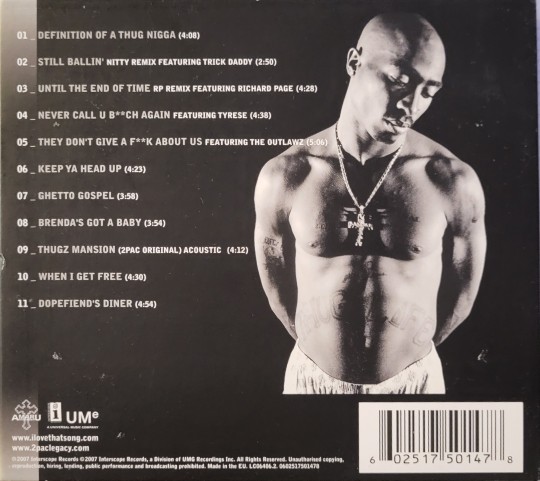

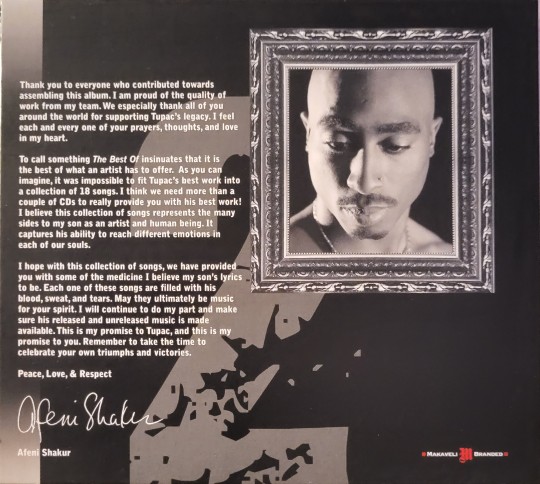

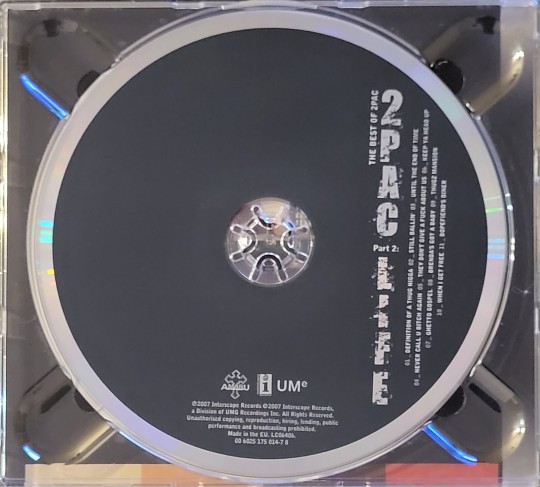

2Pac - Best Of 2Pac: Part 2 - Life

Best Of 2Pac: Part 2 - Life is a posthumous compilation album released by late rapper, Tupac Shakur. The album was released in December 2007, which is a two-part release called “Thug” and “Life”. This compilation contains songs from 2Pac he recorded in 1989 to 1996. The album peaked #77 in the US top albums but peaked #8 in US top rap albums.

Track List:

Definition Of A Thug N**a

Still Ballin’ (Nitty Remix) (feat. Trick Daddy)

Until The End Of Time (RP Remix) (feat. Richard Page)

Never Call U A B***h Again (feat. Tyrese)

They Don’t Give A F**k About Us (feat. The Outlawz)

Keep Ya Head Up

Ghetto Gospel

Brenda’s Got A Baby

Thugz Mansion (2Pac Original) (Acoustic)

When I Get Free

Dopefiend’s Diner

My Top Five Picks:

5th Place - Ghetto Gospel

youtube

4th Place - Keep Ya Head Up

youtube

3rd Place - Dopefiend’s Diner

youtube

2nd Place - Never Call U A B***h Again

youtube

1st Place - Thugz Mansion (Acoustic)

youtube

Picture Gallery:

#2Pac#2Pac Music#Tupac Shakur#Tupac Shakur Music#Best Of 2Pac#Thug Life#Ghetto Gospel#Thugz Mansion#Keep Ya Head Up#Dopefiend's Diner#Until The End Of Time#Still Ballin'#Brenda's Got A Baby#Rap Music#Hip Hop Music#Hip Hop#Hiphop#Hiphop Music#Music#80s Music#90s Music#Pop Addict#YouTube#Black Artists#Music Blogger#Music Blog#Best Of 2Pac Album

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heaves a sigh.

#ic; you are my peach#when will her douchebag dopefiend boytoy return from The War#//i miss their weird psychosexual games#//I Miss Being Problematic

1 note

·

View note

Text

Andrew Vachss: Junkie [Dope Fiend]

— 1 —

Es begann alles damit, dass Charlene mich bat, sie zu töten.

Man muss sie kennen, um zu verstehen, was das bedeutet. Es fiel ihr nicht leicht, diese Worte zu sagen. Nicht, weil sie Angst vor dem Sterben hat — es wäre ein Trost für sie, das weiß ich. Sie will mich einfach nicht allein lassen.

Es sind die Schmerzen. Der Krebs hat ihre Knochen aufgefressen wie ein Rudel vom Winter hungriger Wölfe. Er nagt direkt in ihr Mark. Charlene ist der Schmerz nicht fremd. Sie war nie eine große Frau. Aber sie war stark. Sie leistete immer ihren Beitrag, und mehr. Ich lernte sie auf den Tabakfeldern kennen, und sie zog eine volle Ladung, obwohl sie erst sechzehn Jahre alt war und auch noch schmächtig.

Als wir die Felder zusammen verließen, suchten wir nach etwas Besserem als Saisonarbeit. Das klappte nie richtig, jedenfalls nicht für lange Zeit. Ich bekam Arbeit, doch Charlene konnte keine finden. Oder sie musste kellnern oder so, während ich Arbeitslosengeld bekam. Keiner von uns hat je Sozialhilfe bezogen. So wurden wir nicht erzogen.

Es gab zwar Chancen, aber Charlene ließ sie mich nie wahrnehmen. Ein paar Jungs, mit denen ich aufgewachsen bin, wollten, dass ich in ein paar trockenen Bezirken Schnaps schmuggele. Es gab gutes Geld, wenn man fahren konnte, und sie wussten, dass ich es konnte.

Charlene sagte mir, ich könne das nicht machen. Ich sagte ihr, ich sei der Mann im Haus, wenn ich etwas tun wollte, würde ich es tun. Wenn man gegen das Gesetz verstößt, ist das noch lange nicht falsch, und wir brauchten das Geld. Sie sagte nichts, sondern ging einfach weg und ließ mich dort sitzen.

Ich trank ein Bier und rauchte ein paar Zigaretten und überlegte, wie ich die Sache angehen sollte. Dann kam Charlene wieder ins Zimmer. Sie war so herausgeputzt, als würden wir zum Tanz gehen. Nur, dass sie nicht richtig aussah. Ihr Gesicht war stark geschminkt, nicht so, wie sie es sonst tut. Und ihre Bluse war nicht zugeknöpft. Ich fragte sie, was sie wäre ... Aber bevor ich zu Ende sprechen konnte, erzählte sie mir, dass sie in die Front Street geht, um Geld zu verdienen. Mit Männern. Ich wurde so wütend, dass ich ... Es war das einzige Mal, dass ich meine Hand gegen Charlene erhob. Sie hat sich nicht mal bewegt, stand nur da, die Hände in die Hüften gestemmt. Und ich habe sie nie geschlagen. Ich konnte es nicht. Und sie wusste es.

Charlene machte keine Mätzchen, und ich machte keine Mätzchen. Wir haben es einfach weiter versucht.

Als ich in der Fabrik angestellt wurde, dachten wir, das war's. Es war ein Gewerkschaftsjob, mit Sozialleistungen und allem.

Wir wollten ein paar Babys. Wir hatten lange genug gewartet. Charlene sagte, sie würde ihre Kinder nicht auf die Felder schicken, und ich stimmte ihr zu. Ganz und gar. Als ich dann fest angestellt wurde und meinen Gewerkschaftsausweis bekam, dachten wir, es wäre an der Zeit.

Aber Charlene konnte nicht schwanger werden. Eine der Leistungen, die ich bekam, war diese Krankenversicherung. Also gingen wir zu diesem Ort, den sie uns empfohlen hatten — wie eine Klinik. Sie sagten Charlene, dass ihre ... Eingeweide völlig verrottet waren. Sie hatte diesen Krebs.

Sie versuchten, es herauszuschneiden. Sie kam ins Krankenhaus. Die Krankenkasse bezahlte es. Und sie wurde operiert. Aber der Arzt sagte uns später, dass es zu spät war. Es war in ihren Knochen. Sie konnten nichts mehr tun.

Charlene stirbt also gleich hier in unserem Wohnwagen. Sie kann das verkraften. Ich meine, sie kann es für sich selbst verkraften, zu sterben. Wie ich schon sagte, es gibt nur einen Grund, warum sie nicht gehen will, so viel Schmerzen wie sie jetzt hat.

Die Schmerzen sind das Problem. Charlene kann sie nicht mehr verkraften. Aber die Ärzte von der Krankenkasse sagen, sie können ihr keine Medikamente mehr geben. Es wäre gegen das Gesetz oder so. Sie könnten ihre Lizenz verlieren.

Ich habe dem Arzt klipp und klar gesagt, dass ich ihm nicht glaube. Er hat es mir gezeigt. Auf einem Stück Papier. Ich konnte mir keinen Reim darauf machen. Also sagte ich es ihm noch deutlicher: Wenn er so große Schmerzen hätte, würde man ihm alle Medikamente geben, die er braucht. Dazu hat er nichts gesagt.

Was sie Charlene geben, kommt in speziellen kleinen Flaschen. Der Deckel ist aus Gummi. Da kann man mit der Nadel reinstechen und das rausziehen, was man braucht.

Aber Charlene hat nicht, was sie braucht. Jedes Mal, wenn die Krankenschwester kommt, bittet Charlene sie um mehr. Und die Schwester sagt nur: "Der Doktor hat nichts verschrieben."

"Doktor." Als ob er keinen Namen hätte. Auch keinen braucht. Man könnte genauso gut "König" sagen. Oder sogar "Gott".

Sie lassen drei, vier von diesen Flaschen auf einmal stehen. Sie haben mir gezeigt, wie man die Injektionen gibt. Nicht mal in Charlene selbst. Ich meine, die Nadel steckt schon in ihr drin, alles abgeklebt. Ich fülle die Spritze, dann drücke ich den Kolben in die kleine Stelle, die sie mir gezeigt haben.

Was ihr so weh tut, ist zwischen den Spritzen. Wenn sie keine Kraft mehr hat, um zu kämpfen. Einmal habe ich ihr eine weitere Spritze gegeben, bevor die Zeit verstrichen war, von der die Krankenschwester sagte, dass sie vergehen muss. Und danach fühlte sie sich besser. Ich konnte es sofort sehen. Sie lächelte sogar ein wenig. Aber als die Krankenschwester kam und sah, dass ich nur noch eine halbe Flasche übrig hatte, anstatt der zwei, die ich hätte haben sollen, sagte sie, sie könne nichts tun. Wir mussten das Medikament nehmen, wenn sie es sagten.

Nicht mehr als was sie sagten. Niemals.

Ich fragte sie, so nett ich konnte: "Warum? Ich meine, was machte es schon, wenn Charlene sich in eine dieser Junkies verwandelte? Sie starb sowieso. Das wussten sie alle. Warum konnte sie nicht sterben, ohne so viele Schmerzen zu haben?

Die Krankenschwester sagte kein Wort. Ihre Lippen waren so fest aufeinander gepresst, dass sie die gleiche Farbe wie ihre Uniform hatten.

Schließlich sagte sie: "Wenn Sie zu viel Morphium nehmen, kann es Sie umbringen." Da fing Charlene an zu lachen. Aber der Schmerz ließ ihr das schnell wieder vergehen. Allerdings nicht so schnell, wie die Krankenschwester fortging.

Ich ging zurück zum Arzt. Er sagte mir, dass die DEA die Regeln festlegt. Wenn man zu viele Schmerzmittel verschreibe, würden sie kommen und einem Ärger machen.

Ich fragte ihn, ob ich es richtig mache. Könnte er es mir zeigen? Man sah ihm an, dass er nicht wollte, aber er hatte Angst, also holte er eine der kleinen Flaschen aus dem Kühlschrank und zeigte mir, wie man die Nadel einführt. Ich flehte ihn mit meinen Augen an, mir diese eine zusätzliche Flasche zu geben. Er schaute weg.

— 2 —

Jetzt hat Charlene alle Medikamente, die sie braucht. Es wird nicht mehr lange dauern. Wenn noch etwas übrig ist, wenn sie geht, werde ich es selbst nehmen, damit ich gleich mit ihr mitgehen kann, den gleichen Weg hinab. Wenn nichts übrig bleibt, überlasse ich es dem Gesetz. Jetzt stehen sie schon seit ein paar Tagen draußen und schreien uns durch ihre Schalltrichter an. Sie denken, Charlene wäre eine Geisel.

Das hat uns beiden Spaß gemacht. Es war so lustig, dass Charlene sogar ein bisschen lächelte.

Ich glaube, Charlene ist jetzt eine Drogenabhängige. Ein Junkie. Sie wird bald gehen. Aber sie hat keine Schmerzen mehr.

Und der Doktor auch nicht.

*

(Übersetzung: Thomas Knorra)

*

www.vachss.com | www.vachss.de

0 notes

Text

pro tip if u mention heroin on ur *grunge alt aesthetic* blog while clearly having zero idea what youre fucking talking about i hate you

#fuck you fuck you fuck youuuuuuuuu#leave the unhealthy romanticization of drug abuse to the dopefiends please this aint what u want#my friends are dead 👌#fuck you

0 notes

Note

whts ur ideal man

minimum 6 years older than me...tall because im also tall...dark hair...big sad dopefiend eyes...a bit of a gay vibe...

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

im so hood, i thought fall out boy was sampling dopefiend's diner tbh who is tom

#i only know tupac's version of that song#personal#this is a#shitpost#i was listening to im so hood the song

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

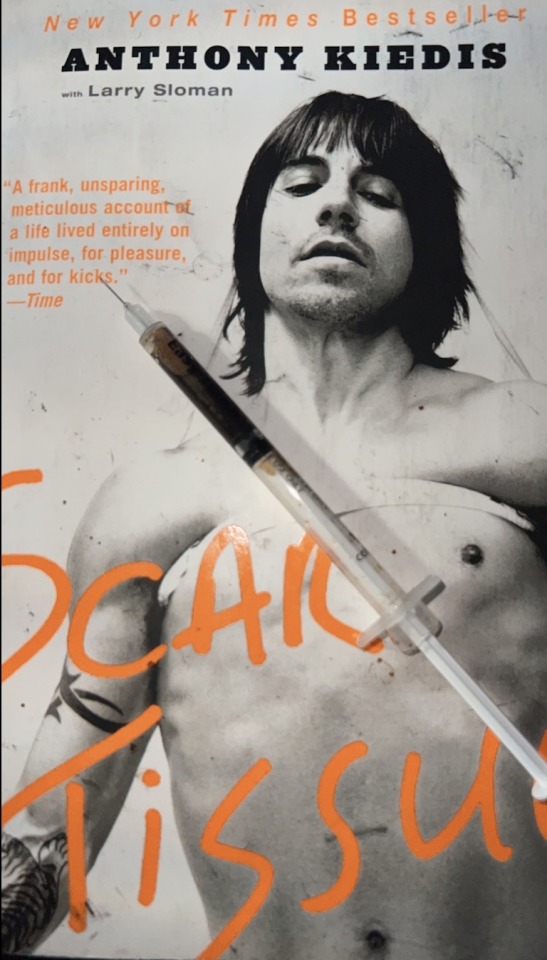

plowing my way thru Anthony Bourdain's testosterone-fueled kitchen dopefiend stories thru out his cheflife in the 80s + 90s in Manhattan and Brooklyn... To diminish the missing of New York City

#it's a good strategy. the guy is totally formidable at sketching effervesce sceneries with his words#I feel such a strong pull to go back there. honestly a lil homesick for a place which isn't mine#*effervescent

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

mansweat got me scratching my arms up and down like a dopefiend just one more hit just one more hit

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Regret has no remedy

Everything we fear has value to us

It's not about regret it's self

But putting a price on something precious

Makes it difficult for us to get satisfaction or appreciation

In the way of life we've had great loss and

Things happen that may seem unlikely

And we to get to unlike something we did

And we wish we could have done specific things

Stuck on the thought like a DopeFiend

Regret is like a drug, just more destructive than heroin

If stuck in regret , the obsession to make it right

Might just be the greatest downfall, loosing your own identity.

I believe in second choice but there is no second chance if you think there is, it is a make believers own ridiculous ideology.

In reality there is no second chance. It's up to us to acknowledge reality. Nobody can change you

Why should you change in the first place

For me I'm a gangster and a raster whatever gangster shit I do I stay with it

Noticing the truth and acknowledging wrong doings is one thing that should come naturally and if it's forced it is done by the feeling of regret , and also from guilty feeling

But no feeling is final .. no feeling is final ..

NO FEELING IS FINAL . I respect how others feel

But NO FEELING IS FINAL

This statement should not be taken out of context because not a lot of people understand what it truly tells

It's an understatement to say that love is a feeling

Love is beyond just feeling .. and it's the final phase in human evolution to live love unconditionally

If love was a feeling then it should be conditional

Hunger is a feeling of lack of food ..but can never be unconditional. Satisfaction is a feeling of great condition

Hunger is a feeling of great disappointment, upset, etc

No other feeling is unconditional I can't just feel cold without reason . I can't feel pain without hurting

I can't be tired without lack of energy

Even in the times of great philosophy no body could actually give an accurate definition of love

Even now with greatest technology nobody knows love or have come to decide or come to discover the remedy or to decode and come up with an equation that solves Love it's self . Only reason is because it is not a feeling, it's already encoded in our DNA. It's up us to acknowledge it and let our souls encounter the body and learn the way of unconditional love through our spiritual transformation merging the very fresh we have with an entire entity that will help us through everything. There is nothing beyond compared to what you see. But if you can see something that is not there to the others you have seen it all

Because if what we've lost ..is an empty garage locked feeling .

This hold us back from the past

Understanding the future is about embracing the passed and not embarrassment of the past

This will punish us and Vanish our dreams

Banishing us from the future.

Regret is we with no remedy for it limits

Your minds to great possibilities

Leaving you with impossible responsibilities

Thus depriving you from personal progression

Causing great aggression.. anger and great depression

Trying to fix how bad you feel for the past actions by changing your present action is a worthless venture into darkness

It will reduce the humanity degrading every atomic cells in your mortal body

Leaving you empty after the failed attempts to fix what's broken comes exhaustion.. and the drive to do it again brings insanity

And even if we manage to fix what we broke

We always want to fix more and more because the satisfaction of replacing regret for accomplishment is inaccurate in the middle of the process of self acknowledgement, we want to be appliciated by the ones we are fixing things with . You or me do we actually think we going to thank someone who slapped us twice In the face just because they bought us face moisturizer twice .

There is no past mixed with the future or the present

In terms of reaction and or action.

No way to fix the past no matter how much changed you have become

Regret has no remedy

Is like a comedy gone wrong in Vegas same script

Isn't gonna go right in Texas

It's like performing to the wrong cloud

We all need a clean slate

That clean slate is about you not feeling regret

Regret comes from a low level some kind of devil

Trying to deprive you of your full potential

I'm not one to think about the past but regret

Always makes me stay stagnant

Moving in a maze

Circulation of the regret is massive insanity we all need to retrieve

1 note

·

View note

Text

“And as far as the pretty girls, I’m glad they’re around…. But I don’t have no cravings for women like I do for my medicine: heroin.

My priority is just not to be sick. How you gonna be with a woman if you’re always sick? What are you gonna do? Just pimp her off? Tell her, “Give me all of your money!”

Nah! I can’t do that nigger shit. I ain’t gonna use or abuse anybody. I already abuse myself with the drugs.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Just like dopefiend Kelly Renee don’t muthafuckng follow me bitches try me I survived and some didn’t but yaw muthafucking won this time muthafuckas try me ms Anna’s Avon account ring a muthafucking bell goddamnit need a copy f my mediccine I told your asses to your muthafucking face bitch try me your nasty ass got herd bitch try me

1 note

·

View note