#edward kynaston

Text

Smart Alec (1951) John Guillermin

June 25th 2023

#smart alec#1951#john guillermin#peter reynolds#leslie dwyer#kynaston reeves#edward lexy#charles hawtrey#mercy haystead#david hurst#david keir

0 notes

Text

the time that glenn howerton was in a gay period-piece play about crossdressing

so awhile back i was poking around glenn howerton's wikipedia looking for movies and such that i might have missed, and i noticed it had a small theatrical section listed. this was never something i'd given much thought in the past, but on this particular occasion i was so hard-up for new Glontent that i decided to see what i could find about the three plays listed there, because i'd never seen anyone else have much luck with that and i love a good internet scavenger hunt. walk with me.

compleat female stage beauty caught my eye right away-- the title of the play itself is interesting, and i happened to know already that the most famous real-life duke of buckingham was the lover of king james. so of course i went delving...

and what should i find but the entire playscript for compleat female stage beauty, For Free, on archive dot org? anyone on earth can rent it and read it for an hour at a time, or for 14 days if you want to really take your time with it. i have to assume that this is NOT common knowledge among sunny fans (or anyone else), as the archive upload only has 99 views at the time of making this post.

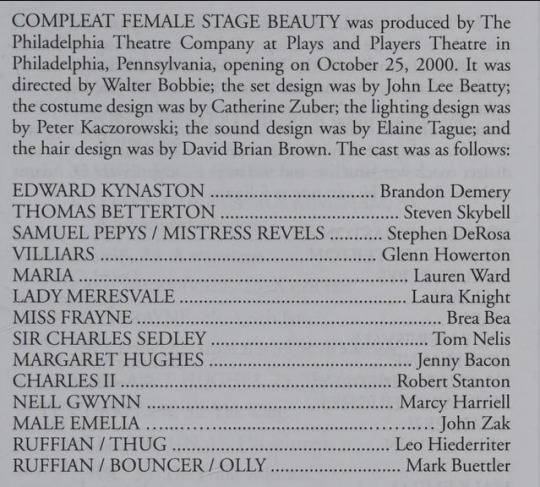

to give a VERY succinct summary of what the play is about-- in the 1660s, during the english restoration, women were allowed to act professionally onstage for the first time in english history. this caused problems for the male actors who had previously made their careers playing female characters, such as edward kynaston, around whom the play centers. outside of his acting career, kynaston is a gay man, and he's in a romantic entanglement with george villiars, the duke of buckingham (NOT the same duke of buckingham who was fucking king james-- that was this villiars' dad. we love gay fathers and their gay sons!) kynaston struggles to find his place in a changing social landscape where it seems as though his talents are no longer needed or wanted.

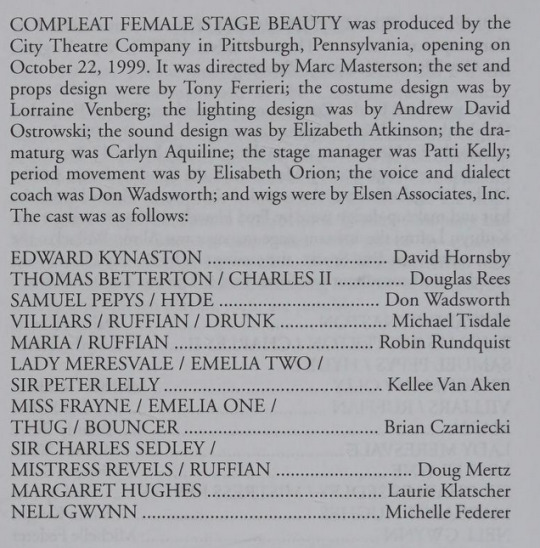

before getting into the script proper, the book has some information about notable early productions of the play. this is great because it pins down a lot of details about glenn's involvement in the show that wikipedia left unanswered, but there's also an unexpected sunny crossover here-- in an even EARLIER production, the lead role was played by david hornsby!

(i also learned over the course of my deep dive on this that glenn's costar, lead actor brandon demery, was a fellow member of glenn's graduating juilliard group!)

things don't end well for kynaston and villiars, but still, the onstage relationship between the two is both electrifying and heartbreaking as it changes over the course of the show.

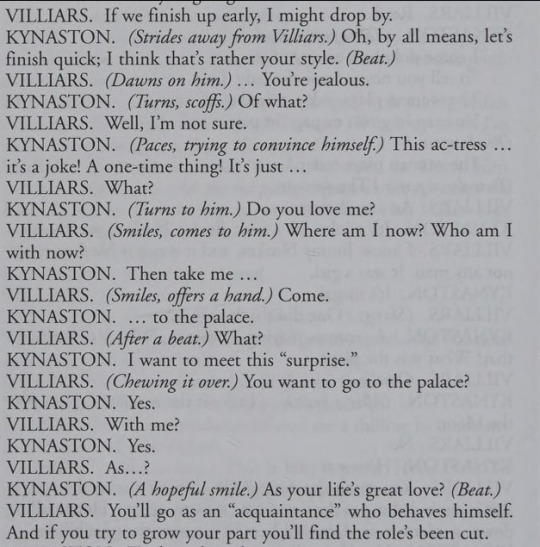

now, this WOULD be where i would include cast pictures or footage or any kind of photos of glenn in this show... but if any such material exists, it's not publicly available. i went so far as to email the publicity and outreach coordinator for the theater that hosted glenn's production of this show to ask if they had any archived materials, but she told me that they didn't.

but this production took place in october of 2000, meaning it was pre-that 80s show, meaning we can all sit and think about how a glenn that looked like This was acting in a gay period piece about crossdressing and gender roles and the mystery of human sexuality. dudes rock.

a bit of a disappointing note to end on, i know, but i really wanted to talk about this play and share it with people!! it's a super interesting and overlooked part of glenn's early career, but also i think the script is fascinating and very well-written in its own right. i definitely encourage yall to check it out on the internet archive if you're interested-- again, it's literally free!

#glenn howerton#iasip#it's always sunny in philadelphia#compleat female stage beauty#this is a longer and more coherent version of a post i made two months ago that got no traction--#--because i accidentally opted out of having my blog's original posts show in any tags. lol. and even lmao#it's crazy what's just like. there and relatively easy to find on the internet if you take the time to look

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

weird how the reigns of king john richard the lionheart have essentially been mythologised. robin hood is a figure of legend, and king john, the sheriff of nottingham, and richard the lionheart all contribute to that legendary view of *checks notes* twelfth-century nottinghamshire? what? it's not like you can find cheesy american films about humphrey kynaston, shropshire, and henry vii/viii, as amusing as that would be. no other period of english history has been so effectively transformed into a fairytale as the reign of king john. baffling. maybe it's just because he makes for a better anthropomorphised cartoon villain than *rolls dice* edward ii

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Claire Danes and Billy Crudup in Stage Beauty (Richard Eyre, 2004)

Cast: Billy Crudup, Claire Danes, Tom Wilkinson, Rupert Everett, Zoë Tapper, Richard Griffiths, Hugh Bonneville, Ben Chaplin, Edward Fox. Screenplay: Jeffrey Hatcher, based on his play. Cinematography: Andrew Dunn. Production design: Jim Clay. Film editing: Tariq Anwar. Music: George Fenton.

It's a measure of how the discourse on sexual identity has changed since 2004 that Stage Beauty, in which it is a central theme, seems now to have missed the mark completely. Billy Crudup plays Edward Kynaston, an actor in Restoration London who was noted for his work in female roles at a time when such parts were usually still played by boys and men. Kynaston, as the film tells us, was praised by the diarist Samuel Pepys as "the loveliest lady that ever I saw in my life." As the film begins, he is performing as Desdemona in a production of Othello, and is aided by a dresser, Maria (Claire Danes), who longs to act. After his performance ends, she borrows his wig, clothes, and props, and performs in a local tavern as "Margaret Hughes." When King Charles II (Rupert Everett) lifts the ban on women appearing on stage, Kynaston finds his career threatened, and when the king's mistress, Nell Gwynn (Zoë Tapper), overhears him fulminating about the inadequacy of actresses, she persuades the king to forbid men from playing women's roles: The king gives as his reason that it encourages "sodomy." Meanwhile, Maria has taken advantage of the ban to rise in her career, and calls upon Kynaston to coach her in his most famous role, Desdemona, while teaching him how to act like a man on stage. The premise allows for some insight into the nature of gender, but the film never approaches it satisfactorily. Instead, we have a conventional ending which suggests that Kynaston and Maria fell in love. Earlier in the film, Kynaston is shown in a same-sex relationship with George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham (Ben Chaplin), who leaves him to get married. The film never quite deals with whether Kynaston is gay, bi, sexually fluid, or simply somehow confused by having been celebrated as a beautiful woman. While it's risky to apply 21st-century psychology to 17th-century sexual mores, Stage Beauty's general indifference to historical accuracy seems to demand that it do so. As unsatisfactory as it is, Stage Beauty has a fine performance by Crudup and he and Danes have good chemistry together.

5 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

The Stars Look Down (1940) | Michael Redgrave | Margaret Lockwood |

he Stars Look Down movie is a British film released in 1940. This classic film is based on A. J. Cronin's novel was written in 1935 with the same title. The film is about injustices in a mining town in North East England. Coal miners, who are led by Robert "Bob" Fenwick, vote to go on strike. The miners are refusing to work in a particular section of the mine. The reason is due to the great danger of flooding. Tensions rise as the strikers go hungry. Cast Michael Redgrave as David "Davey" Fenwick Margaret Lockwood as Jenny Sunley Emlyn Williams as Joe Gowlan Nancy Price as Martha Fenwick Allan Jeayes as Richard Barras Edward Rigby as Robert "Bob" Fenwick Linden Travers as Mrs. Laura Millington Cecil Parker as Stanley Millington Milton Rosmer as Harry Nugent, MP George Carney as Slogger Gowlan Ivor Barnard as Wept Olga Lindo as Mrs. Sunley Desmond Tester as Hughie Fenwick David Markham as Arthur Barras Aubrey Mallalieu as Hudspeth Kynaston Reeves as Strother Clive Baxter as Pat Reedy James Harcourt as Will Frederick Burtwell as Union Official Dorothy Hamilton as Mrs. Reedy Frank Atkinson as Miner David Horne as Mr. Wilkins Edmund Willard as Mr. Ramage Ben Williams as Harry Brace Scott Harrold as Schoolmaster Strother (as Scott Harold) You are invited to join the channel so that Mr. P can notify you when new videos are uploaded, https://www.youtube.com/@nrpsmovieclassics

0 notes

Text

Top 5 Billy Crudup Performances That Hit Me With Silly Love-Stricken Bitch Disease:

1. Stage Beauty

2. Almost Famous

3. Big Fish

4. Rudderless

5. Spotlight

#billy crudup#stage beauty#almost famous#big fish#rudderless#spotlight#russell hammond#edward kynaston#will bloom#eric macleish

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

GOTHS

or the COMPLEAT FEMALE STAGE BEAUTY

Being the History of Edward Kynaston and the Restoration Stage

i. rain in soho

but no one’s dancing, no one’s dancing down there

though you repent and don sackcloth and try to make nice / you can’t cross the same river twice

we played for you but you would not sing / no one was going to get away with anything

Wheareas the distressed Estate of Ireland, steeped in her own Blood, and the distracted Estate of England, threatened with a Cloud of Blood by a Civil War, call for all possible Means to appease and avert the Wrath of God, appearing in these Judgements; amongst which, Fasting and Prayer, having been often tried to be very effetual, have been lately and are still enjoined...It is therefore thought fit, and Ordained, by the Lords and Commons in this Parliament assembled, That while these sad causes and set Times of Humiliation do continue, Public Stage Plays shall cease, and be forbore, instead of which are recommended to the People of this Land the profitable and seasonable considerations of Repentance, Reconciliation, and Peace with God.

parliamentary directive, 2 september 1642

ii. andrew eldritch is moving back to leeds

there's indifference on the wind but a faint gust of hope / at a club nobody goes to with a musty velvet rope

no sign to mark its going, no tombstone for its grave / there will be goodbyes by dozens so practice being brave

Our Musike that was held so delectable and precious, that they scorned to come to a Taverne under twentie shillings salary for two houres, now wander with their Instruments under their cloaks, I meant such as have any, into all houses of good fellowship, saluting every roome where there is company, with Will you have any musike Gentlemen?

the actors remonstrance or complaint for the silencing of their profession and banishment from their severall play-houses, 1643

iii. the grey king and the silver flame attunement

trying to get our shapes back

doomed sailors / born high by the waves / wild with wonder / leather and lace and good friends / most of them good, most of them friendly

Tho’ as I have before observed, Women were not admitted to the Stage, ’till the return of King Charles, yet it could not be so suddenly supply’d with them, but there was still a Necessity, for some time, to put the handsomest young Men into Petticoats; which Kynaston was then said to have worn, with Success.

colley cibber’s theatrical autobiography, 1740

Kynaston at that time was so beautiful a youth, that the Ladies of Quality prided themselves in taking him with them in their coaches, to Hyde Park, in his theatrical Habit after the Play....Of this truth I had the curiosity to enquire and had it confirmed from his own mouth in his advanced age.

colley cibber’s theatrical autobiography, 1740

iv. we do it different on the west coast

the papers write about it back in england

there’s a whole new world just up around the corner

And we do likewise permit and give leave that all the women’s parts to be acted in either of the said two companies for the time to come may be performed by women, so long as these recreations, which by reason of the abuses aforesaid were scandalous and offensive, may by such reformation be esteemed not only harmless delights but useful and constructive representations of humane life to such of our good subjects as shall resort to see the same.

letter from king charles to the reopened theaters, 1660

I come, unknown to any of the rest

To tell you news, I saw the lady drest;

The woman playes today, mistake me not,

No man in gown, or page in petticoat;

A woman to my knowledge.

prologue for the occasion of introducing “the first woman that came to act on the stage, in the tragedy called the moor of venice,” thomas jordan, 1660

v. unicorn tolerance

hard limits fade into memory once broken through

love to the ghosts who taught me everything I know

In the course of this comic subplot, Lady Would-be, Sir Politic’s wife, is convinced that her husband is having an illicit affair, and the first object of her suspicion is the character Peregrine, who is always in his company. She assumes, in fact, that he is a woman in male disguise, but the comedy of the scene depends on her suggesting male–male erotics...The joke works by playing on the supposedly disguised gender of Peregrine, and Lady Would-be’s accusations are vivid in the way that they insist on gender deviation...All these comic effects are intensified, however, when the actor, like Kynaston, prettily and softly handsome, is known to everyone in the theater as the recent heroine Arthiopa (or Aglaura or Princess Ismena). The very actor who has so recently and so popularly been a woman is accused on stage of being a woman in disguise. Surely he was given this role for the uproar this scene would cause among his admirers in the audience.

“‘the queen was not shav’d yet’: edward kynaston and the regendering of the restoration stage, george e. haggerty

vi. stench of the unburied

say what you will for the effort / you can’t fault the technique

keep climbing forever / try to keep the torch lit

The King coming a little before his usual time to a Tragedy, found the Actors not ready to begin, when his Majesty not chusing to have as much Patience as his good Subjects, sent to them, to know the Meaning of it; upon which the Master of the Company come to the Box, and rightly judging, that the best Excuse for their Default, would be the true one, fairly told his Majesty. that the Queen was not shav’d yet: The King, whose good Humour lov’d to laugh at a Jest, as well as to make one, accepted the Excuse, which serv’d to divert him, till the male Queen cou’d be effeminated.

colley cibber’s theatrical autobiography, 1740

vii. wear black

all this coast is vanishing / check me out, I can’t blend in / check me out, I’m young and ravishing

see me keeper of the source code

Stunningly beautiful in earlier scenes, in various poses and various costumes, here Arthiopa enters with “her haire dishevell’d,” a shamed and brutalized victim, and she fulfills the abject potential of the opening scene as she succumbs to her feelings here. This type of pathetic heroine became the specialty of Kynaston, and in these roles he was rarely equaled, as John Downes’s remarks about Kynaston’s performance in this play suggest. For Downes, Kynaston “being then very Young Made a Compleat Female Stage Beauty, performing his Parts so well, especially Arthiopa and Aglaura, being Parts greatly moving Compassion and Pity; that it has since been Disputable among the Judicious, whether any woman that succeeded him so Sensibly touch’d the audience as he.”

“‘the queen was not shav’d yet’: edward kynaston and the regendering of the restoration stage, george e. haggerty

viii. paid in cocaine

baubles and bangles, a lost age / still all aglow with the radiance of the stage

that’s who I was / this is who I am

The last and arguably best known boy actor to play Desdemona on the Restoration stage, Edward Kynaston, was playing female parts until his early 20s. In 1660, Desdemona was the first major stage part to be played by any English actress on the professional stage, and the boy player tradition declined rapidly after this.

othello, stuart hampton-reeves

Cassio, played by Edward Kynaston (a pre-Restoration actor who was also noted for playing the woman’s part), is simply, “the Moor’s Lieutenant General.”

description of a 1681 cast list in othello: a contextual history, virginia mason vaughan

ix. rage of travers

they break the news to me so gentle / but I start to feel sentimental

nobody wants to hear the twelve-bar blues / from a guy in platform shoes

Because the film [Stage Beauty] openly invites us to understand this climactic scene as a scene of triumph, we are asked to understand that an anachronistically modern conception of acting, in which art is indistinguishable from nature, is superior to historical conceptions of acting as personation—a superiority recognized even by the seventeenth-century theater patrons in the film—and that the elimination of cross-gender performance enables this artistic progress. The shots of an ecstatic audience on their feet shouting “Hughes! Hughes!” also make this a “recognition scene” that acknowledges a presumed liberal audience that desires progress in gender relations and takes satisfaction in Maria's professional success. Ultimately, though, the success is Kynaston's. In gaining control over and finally “killing” the character that, in the film's terms, was responsible for smothering his masculine nature, Kynaston comes into his own. As he says backstage, “I finally got the death scene right.”

“‘what’s the trick in that?’ performing gender and history in stage beauty, cameron mcfarlane

x. shelved

the ride’s over, I know / but I’m not ready to go

For male actors, especially boy actors, this meant that some major adjusting had to occur. Male Restoration actors began to have a reduced pool of roles to choose from, playing only male characters – though they might play “in skirts” (in comedic female roles) for a broad comic effect, as in the Renaissance. Masculinity in male roles became more definitive and limited with the rise of the actress, and was reinforced by patriarchal society at large.

“bawds, babes, and breeches: regendering theater after the english restoration,” laura larson

xi. for the portuguese goth metal bands

star-crossed lovers and their tragic fates

finally head west, but it’s a dead end / come home dead broke but still among friends

there’s not so many of us / but you don’t know any of us

Restoration history is primarily written through the circulation of well-known anecdotal evidence by scholars, which rarely includes representations of actresses, or women for that matter, and becomes an incomplete and biased narrative of women’s lives that is canonized. This severe lack of primary source material is one of the main factors in the disagreement among Restoration scholars, since there can be many different analyses of the same sources. Indeed, one is hard-pressed to find anything beyond a brief mention of women on stage in diaries or papers, and the relevant play material – prologues and epilogues written for specific performances – are largely edited out of available modern play texts.

“bawds, babes, and breeches: regendering theater after the english restoration,” laura larson

xii. abandoned flesh

but the world came to agree / what you see is what you get and what you get is what you see

you and me and all of us / are gonna have to find a job / because the world will never know or understand / the suffocated splendor / of the once and future goth band

Did not the Boys Act Women's Parts Last Age?

Till We in pitty to the Barren Stage

Came to Reform your Eyes that went astray,

And taught you Passion the true English Way.

Have not the Women of the Stage done this?

Nay, took all Shapes, and used most means to Please.

epilogue to elkanah settle’s the conquest of china by the tartars, spoken by leading lady mary lee, 1676

#the mountain goats#edward kynaston#please clap this took me so long and I don't know anything about restoration theater

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The London theater stood at the center of urban life in Restoration and eighteenth-century England. Women were vital participants in its success as actresses, playwrights, patrons, orange girls and pawnbrokers, costume makers and vendors. Star players such as Elizabeth Barry, the subject of Otway’s poetic lines, linked public fame to audience affection through the magnetic theatrical appeal of their palpable feminine presence. Barry and other actresses openly violated the conventional injunction aimed at ambitious women during this historical period: “Your sex’s glory,” enjoined Edward Young in Love of Fame (1725–28), “’tis, to shine unknown; / Of all applause be fondest of your own.” Ranging in reputation from prostitutes to socially respectable ladies, early actresses afford a dynamic cultural site for examining unequivocally public women in a period that ostensibly fostered domesticity as an ideal.

Social and economic forces encouraged lively social exchange and a thriving print culture that was crucial to the construction of celebrity. Actors’ worth in the theatrical marketplace fluctuated depending upon public demand throughout a period that witnessed the change from a powerful aristocracy’s dominance to an increasingly urban landscape of merchants and traders. Women’s emergence as celebrities culminated at century’s end in the staggering popularity of Sarah Siddons, whose ardent fans breakfasted near the playhouse to claim much-coveted tickets. Yet the concepts of “woman” and “actor” were often at odds in this formative time that balanced a long-standing patronage system together with an emergent market economy.

At first women who engaged in theatrical activities seem to have been regarded as curiosities in the same aberrant category as the exotics who peopled fairs and other popular entertainments—the hog-faced woman, hairy wench, or baboons—exhibited in public for commercial return in the seventeenth century. By what definition were these first actresses who displayed an unprecedented public femininity to be regarded as women? How could one reconcile “the rarity and beauty of their talents” with “the discredit of employing them”? How were the passionate feelings aroused in both sexes in the audience to be channeled into higher profits? The economic realities of the theater, I argue here, disrupted any simple staging of femininity. Throughout the earlier seventeenth century and even during the Interregnum, women participated sporadically in court entertainments, public theatricality, popular festival rituals, and guild performances, but no women appeared in London’s legitimate theaters until the Restoration in 1660.

Male actors had earlier interpreted the roles of Cleopatra and Desdemona, Kate and Ophelia, in the often eroticized parts Shakespeare created with the expectation that boys would play them. Partly as a response to the shortage of experienced boy actors caused by the closing of the theaters in 1642 for nearly two decades, the restriction against women’s performing was lifted upon the restoration of Charles II, although Edward Kynaston of Duke’s Company (whom Samuel Pepys called “the loveliest lady that ever I saw in my life”), as well as James Nokes and Charles Hart of King’s Company continued to perform occasionally as women. …More than a century later Sarah Siddons’ early biographer, Thomas Campbell, attributed actresses’ assumption of women’s roles to Puritan fears that men’s dressing in female attire contradicted Levitical law in the Book of Deuteronomy, a concern he dismisses, for the fact that actresses would have had to utter licentious language was more likely to have been a legitimate concern.

The itinerant nature of the early English touring companies contributed to making women’s participation unacceptable because of their being suspected to be prostitutes, and the establishment of patent theaters provided a stable, potentially more reputable, location. The hoped-for effect of actresses coming to the stage to usurp the gender-bending place of Renaissance boys and supplant men in “skirts roles” did not rid the stage of effeminacy; but as dramatic roles for real women were for the first time invented and then expanded, the Restoration theater, and the new plays that were written for it, became more fully rooted in the female body. It seems likely that the most compelling reason that women had been prevented from appearing on stage was that actors feared the economic competition which actresses would bring to the commercial theater.

Memoirists, managers, fellow actors, and audience members consistently understated the cultural—and economic—power that actresses might wield. In addition, female dramatists after the turn of the century (most significantly Susanna Centlivre, Susannah Cibber, and later Hannah Cowley, Frances Burney, Elizabeth Griffith, and Elizabeth Inchbald) were attracted to the burgeoning business of writing for the newly feminized stage. In short, women’s indispensability to the success of the commercial theater was firmly, if sometimes grudgingly, established over the course of eighteenth century. Though professional female players did not mount the legitimate stage until the Restoration in England, some craft guilds in earlier periods may have allowed young women, in addition to the occasional itinerant female stroller, to act in the French and English plays they produced.

Medieval convents would have staged same-sex performances in which the nuns participated (Shapiro, 178), and women occasionally appeared in Tudor pageants and popular entertainments. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries French, Italian, and Spanish women had been permitted to perform as professionals, though permission was at times rescinded. These early actresses were also forbidden to cross-dress in order to keep sexual difference clearly defined. Performing commedia dell’arte in 1564, the Italian actress Lucrezia Senese was probably the first European professional woman player, followed later by the Roman Flaminia and Isabella Andreini of Padua, although the Papal States decree required that castrati should substitute for women until the late eighteenth century. Italian companies traveling in France began to encourage the cultivation of homegrown actresses first in Bordeaux and then in Paris.

Actresses also appeared in Spain, performing with an Italian troupe in 1587, though they were again outlawed in Spain from 1596 to 1600, at which time only married women could act in public. Abbé Hedelin cautioned that no single woman should act unless her mother or father was a member of the company, and that widows must marry with a year and half if they were to perform. While such rules are commonly assumed to have been designed to protect actresses’ chastity, restricting their marital status would also have controlled their access to their earnings. In the Restoration and eighteenth century, married couples who were both actors were often listed as earning a single shared wage, even when the wife commanded the superior salary.

Happenstance or luck is often an important part of the prevailing narrative as to why women were recruited into the theater, but it also seems possible that placing themselves within listening range of well-known playwrights, managers, or other actors may well have been, rather than an accident, a clever young woman’s taking an opportunity to audition for a potentially lucrative position in order to support herself and incidentally to regain the status that her family had lost. A considerable number of actresses were “discovered” in relatively public places. Charles Taylor insisted that George Farquhar was totally responsible for Oldfield’s becoming an actress rather than attributing it to her initiative after her eloquent dramatic reading at Mitre Tavern in St. James’s Market led the playwright to become her patron.

Peg Woffington, the daughter of a journeyman bricklayer and washerwoman in Dublin, was apprenticed at age twelve to Mademoiselle Violante after the Italian gymnast and equilibrist noticed her natural talent. Kitty Clive’s fortuitously singing within hearing of the Beef-steak Club at Bell Tavern may have led to her promotion to the stage by Club members Mr. Beard and Mr. Dunstall—though William Chetwood insists instead that he and Theophilus Cibber recommended her to Colley Cibber upon hearing her lilting voice.10 Perhaps Woffington, Oldfield, and Clive firmly planted themselves within close proximity to influential men to expedite their ascent to the stage. It is not known whether women were apprenticed to master actors after they began appearing on the stage in 1660, and it is beyond the scope of this study to provide a full history of thespian education.

Renaissance practices would not have included women, of course, and not a great deal is known about actors’ training before or after 1660. It is clear, however, that early modern apprentices in the craft of acting were usually tutored by individual masters to whom they were bound, rather than being instructed within the larger theater troupe, and many boys continued with their training for the requisite seven years. The boys acted in adult roles when they reached majority, though adult men also took on skirts roles after 1642. Indentured workers, some of whom may have been young adults, may have played female roles under duress because a stigma of effeminacy was attached to them. The “play-boys” taking the roles of women characters in the Renaissance were often apprentices to grocer or weaver guilds and most likely occupied a lower social standing than the adult male actors who lived in the homes of their masters (Shapiro, 183).

As manufacturing, service, and construction industries declined, there was less need to train new workers, who turned instead to the newly developing trades. Tutors assumed a proprietary role over trained apprentices and could lease or even sell them to theater companies. Corrupt and abusive practices evolved from the expectation that masters sometimes adopted the role of moral guide and disciplinarian. Female performers introduced into this situation suffered special difficulties and could easily have been sexually compromised. As Michael Shapiro rightly pointed out, “It is hard to imagine many literate girls or young women whose families would have allowed them to become apprentices (which would have meant leaving home and moving into the master’s house) at an age probably even earlier . . . than for . . . domestic service” (188), but unexpected financial strains might have induced families to indenture their daughters if, for example, they could be apprenticed into the relative safety of a widow’s home.

Women were sometimes taken into a noble family and treated as one of their own, as in the case of Elizabeth Barry who became part of Sir William and Lady Davenant’s household, or Anne Bracegirdle who lived with the acting family of the Bettertons. John Harold Wilson maintains that the theater companies would have relied for potential actresses on “genteel poor” women who merely assumed an air of refinement, but this argument rests on the questionable assumption that performing the roles of Restoration heroines required less labor, skill, and talent than acting demanded of men. Another avenue to the theater would have been as tradeswomen such as seamstresses, dressers, milliners, and spinsters who were subsidiary to the theater but absolutely essential to it.

Male apprentices were bound not to marry during their indenture, but female apprentices, constrained until age twenty-one, may well have sought to wed in order to be freed from any obligation to their masters. The historical relationship between apprentices to the theater and actresses is not simple, though they were in fact very closely intertwined. For example, the prologue to George Farquhar’s The Constant Couple (1699) implies a petty criminal relationship of boy actors to their masters, one that is also explored later in George Lillo’s bourgeois tragedy, The London Merchant (1731): And now the modish Prentice he implores, Who with his Master’s Cash stol’n out of Doors, Imploys it on a brace of—Honourable Whores.

Because actor boys often played whores and may have been objects of sexual desire for the adult male actors, the assumption that actresses could also be treated as erotic playthings may suggest a continuation rather than a break with the practices of predatory actors before the Interregnum. For example, in 1688 apprentice boys attacked bawdy houses and rioted against prostitutes, but the boys, provoked by their fear of sexual and economic competition from whores, may have wanted to protest more generally the low wages and poor conditions of laborers. The violence against female prostitutes may have erupted because they, like actresses, posed a special challenge to masculine prerogative of various sorts. The fledgling actors, Katherine Romack persuasively argues, may also have been attempting to preserve the homosocial situation that pertained before women professionals came to the stage.

We might conclude from the evidence available that actresses, like the whores with whom they were so closely aligned, were poised to become both sexual and economic rivals to boy actors and apprentices. The line between female apprentices and sex workers was thus very finely drawn from the Restoration on. Prostitution was sometimes used as a paradigmatic catch-all term for female labor of any sort, as revealed in the mid-century burlesque pamphlet that purports to be actress Ann Catley’s biography: “The word Prostitute does not always Mean a W-- but is used also, to signify any Person that does any Thing for Hire.” Similarly, a treatise entitled Chiron: or, the mental optician, jests at the too refined sensibilities of the female apprentice who refused to carry linens to a young gentlemen’s chambers for fear of being sexually compromised, because she recognized that her job was at stake, and that “her cruel mistress . . . would sell her at the market price.”

How then did women become trained actresses when there were so few formal opportunities to be tutored in their craft? Our knowledge of the training available to fledging actresses is relatively slim. The London nursery that Lady Davenant formed in 1671 had disappeared by the 1680s, but there is some evidence that nurseries for young actors persisted until the late nineteenth century. The two legitimate London companies in the Restoration shared a joint nursery, and another performance school was set up in Norwich. Training for Restoration actors also took place at the George Jolly Hatton Garden Nursery established by Thomas Killigrew. On 30 March 1664 Davenant and Killigrew were authorized to set up a playhouse “for ye instructing of Boyes & Girles in ye Art of Acting . . . .in the nature of a nursery.”

Elizabeth Howe suggests that the coterie nature of the Restoration theater encouraged hothouse breeding for the few actresses determined to merit presentation at court: “The actresses apparently represent an exception to the general decline in professional opportunities for women after 1660.” But it seems most likely that aspiring women players participated in a more informal kind of apprentice system than that which obtained among the actors. Some actresses learned gestures, movement, and enunciation from the playwrights who wrote for them, or from the male actors who were their lovers or husbands, as in the case of Mary Saunderson and her husband Thomas Betterton. A woman housekeeper taught acting to girls while Betterton instructed the boys in his company (Freeburn, 152). The Bettertons schooled Anne Bracegirdle and Mary Porter, and Lady Davenant is believed to have tutored Elizabeth Barry for her role in The Man of Mode.

Lord Rochester was long rumored to have also instructed Barry, albeit with differing motivations; and though the assertion lacks credibility because he was not residing in London on the appropriate dates, it does suggest that lovers may have served as tutors as well. Oldfield’s biography maintains that her lover Maynwaring’s training contributed heavily to her success as a player (Egerton, 4). From the beginning, actresses would have been recruited primarily from among those who could read, or at least memorize easily by rote, requiring their possessing a certain basic quickness and education. A narrow time gap existed between performance and rehearsal with little time allotted for practice, and individual actresses also prepared lines on their own with occasional coaching from a fellow actor who might have greater experience.

In some companies a trial period of acting for three months without salary resembled a sort of apprenticeship that would have allowed inexperienced players to attend rehearsals and to attempt to learn parts from veteran members of the company. At the turn into the eighteenth century, however, training would still have been haphazard. As a second generation of actresses developed, they garnered skills and techniques from the seasoned senior players. Occasionally mothers or sisters of actresses imparted their understanding of specific dramatic parts. Kitty Clive protested that she coached a fellow actress at her own expense, and that she deserved greater remuneration for those services, especially when she compared her regular salary to the income of Susannah Cibber, who made about twice as much.

Clive demanded that Garrick raise her salary to compensate for the expenses she had incurred while coaching the younger woman: “The year Mrs. Vincent Came on the Stage, it cost me above five Pound to go to and from London to rehears with her and teach her the Part of Polly, I coud not be calld on to do it, as it was long before the house oppend, it was to oblige Mr Garrick.” Mary Betterton was also a generous mentor: “When she quitted the Stage, several good Actresses were the better for her Instruction” (Memoirs, 1731). When schools of acting differed, such inbred tutoring could backfire. Garrick complains that Jane Cibber’s training in tragedy by Colley Cibber was inadequate, and that “the Young Lady may have Genius for all I know, but if she has, it is so eclips’d by the Manner of speaking ye Laureat has taught her, that I am afraid it will not do—We differ greatly in our Notion of Acting (in Tragedy I mean) & If he is right I am & ever shall be in ye wrong road.”

Charles Macklin’s memoirs speak of Mrs. Dancer (who later became Mrs. Barry and Mrs. Crawford) whose skills were magnificently improved after “the silver-toned [Mr.] Barry” coached her. As is well-known, Sarah Siddons learned her craft on the provincial circuit, and Dublin also frequently served as a training ground for women players. Acting on the legitimate stage continued to be a sought-after means of earning a living, and star actresses regularly fielded appeals from young hopefuls. George Anne Bellamy remarks that while she played at the Edinburgh theater, “an incredible number” of letters came to her “from itinerant players applying to be engaged. . . . They generally wrote in such a style, as to shew they all thought themselves Garricks and Cibbers.”

Young apprentice workers in many trades were seduced by the attractions of celebrity and the hope that instant success would relieve the drudgery of their manual labor. Their plebeian idealization of acting as a plausible alternative serves as a material example of the appeal that stage models of identity could hold for the working-class imagination. Both men and women alike romanticized performative labor because it seemed to offer an alternative to lifelong drudgery with potential to yield an economic windfall and unprecedented class mobility. The threat was sufficient for Samuel Richardson to write The Apprentice’s Vade Mecum (1734), which defends the statutory regulations against apprentices frequenting the theater, and the tract severely warns the young men about the stage’s corrupting effect. Plays and other popular entertainments, Richardson cautions, pandered to low standards of taste and tempted lower tradespersons to avoid disciplined work and to affect high style.

Though apprentices apparently accrued some discretionary income through legitimate means, their conspicuous consumption attracted the kind of envy and animosity usually aimed at upwardly mobile nabobs returning from travels abroad. The criticisms were especially directed at the finely dressed apprentices who thwarted sumptuary laws and dared to display confusing markers of social class. The Lord Mayor and Common Council had required apprentices to dress in the apparel their masters gave them as indicative of their station. They were to wear only woolen caps, the plainest of doublets sans ruffles, fancy pumps, or jewelry, and to carry no sword: “And ’tis now to be wish’d that some such good Law were thought of, to restrain the far more destructive Practices of our modern Apprentices, viz. those of Whore and Horse-keeping, frequenting Tavern Clubs and Playhouses, and their great excesses in Cloaths, Linen, Perriwigs, Gold and Silver Watches, &c.”

For the worst offender against sumptuary regulations, the term of indenture could be extended beyond the agreed-upon time. As these young workers accrued capital, they threatened to abandon industrious application to their trades, the very means that had earned them the shillings necessary to purchase a theater ticket. Though these public directives were largely directed at male apprentices, women workers were equally attracted to the stage. In 1729 the justices of the peace carped that Thomas Odell’s theater in Ayliffe Street, like other London theaters, drew “Tradesmans Servants and others from their lawful Callings, and corrupt[ed] their Manners.” This was exacerbated because the six o’clock curtain time conflicted with business hours that typically extended until eight or nine at night for apprentice workers (Vade Mecum, vi).

Plays were specifically designed to be performed for apprentices on work-free holidays, the best-known being of course Lillo’s didactic tragedy, The London Merchant, produced for the first time three years before Richardson’s manual. Warned against neglecting business, and against the addictive quality of theater, the frivolous nature of the entertainment, and the temptation to whore with lewd women in the theatrical environs, apprentices were enjoined to be modest and frugal, religious and affable, and obsequious to their masters. In a related example, the Weekly Miscellany (8 March 1735) made reference to the rowdiness of apprentices at the opening of a new playhouse. The poorer apprentices sat in the upper gallery with the footmen, though those with a few more shillings to spend occupied the boxes and sideboxes.

Crowding into the mid-eighteenth-century theater, the notoriously ill-behaved apprentices sitting on the stage “three or four rows deep” interfered with productions. Tate Wilkinson describes the unruly scene: “A performer on a popular night could not step his foot with safety, lest he either should thereby hurt or offend, or be thrown down amongst scores of idle tipsy apprentices.” The theater, then, sorely tempted apprentices into engaging in immoral behavior and disrupting the social order from the bottom up. Arthur Murphy’s The Apprentice, the afterpiece to Southerne’s Oroonoko performed on 2 January 1756, gives a specific instance of the special perils awaiting stage-struck plebeian women. It features Dick and Charlotte, apprentices who haunt the theater in hopes of learning the craft of acting.

…Finding training to ascend to the stage was a risky and costly business for impressionable female apprentices who sought to become celebrated players through the fantastic imaginings made available every night of the season for the price of a theater ticket. Seeming to be unmoored from the fathers and husbands who defined their status, the social rank of women players was, as I have been arguing, more complicated than it was for most men. Their uncertain class position brought into play the sign of the “actress-as-whore,” if not the actuality of trading money for sex, though it is too simple to declare that “society assumed that a woman who displayed herself on the public stage was probably a whore.”

The often indeterminate social class of the newly professionalized actresses, made opaque through the diverse roles they played and the clothes they wore, could also empower them. Laura Rosenthal has argued that the actress, as “an untitled and unmonied professional . . . theatricalized an emergent instability of class identity” and destabilized real gender relations because male audience members “forgot” that an actress playing an aristocratic lady was simply inhabiting a role and was not properly marriageable in her own person. That actresses often wore the cast-off clothing of noblewomen may well have heightened their ability to attract libertine aristocrats, and actresses in turn sometimes bequeathed clothing, costumes, and jewels to their servants.

Tate Wilkinson is among those who complained that the fancy dress of women servants on stage, including their elaborate headdresses and satin shoes, encouraged sartorial upstarts in the audience to affect elevated social standing: “I have seen Mrs. Woffington dressed in high taste for Mrs. Phillis, for then all ladies’ companions or gentlewomen’s gentlewomen, actually appeared in that style of dress; nay, even the comical Clive dressed her Chambermaids, Lappet, Lettice, & c. in the same manner, authorised from what custom had warranted when they were in their younger days” (Memoirs, 4: 89). ….The Servants Calling (1725) urged employers to refrain from the common practice of giving fine clothes to their servants whose heads are “fill’d with Notions of their Advancement,” cautioning them to avoid dressing above their degree, and to “act the Part that belongs to them.”

Actresses violated these injunctions both as benefactors and as willing recipients of gifts of clothing from their patrons and admirers. In life and on the stage, then, the star actress taught lesser beings—the common servant girl and the aspiring apprentice—the art of social emulation. Moving through the social classes in drama and in life while mastering the etiquette of nobility, actresses revealed the performative nature of social status to audiences consisting of tradespersons, citizens’ wives, ladies of quality, and even queens The memoirs of actresses attempted to reconcile the fact that even though these women were not queens, they could convincingly impersonate the elite ranks and inspire the kind of adulation usually reserved for them; they represented the imagined possibilities that social change could bring.”

- Felicity Nussbaum, “The Economies of Celebrity.” in Rival Queens: Actresses, Performance, and the Eighteenth-Century British Theater

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

ACTING

The history of acting began in Ancient Rome and Greece, where it is deep-seated arise. The first dithyramb, such as songs that tells the story and honor the gods, are composted in Athens, Greece, in 700 B.C. Dithyramb was formed by young boys and men who would tell a story into multiple accounts by dancing and singing. The Festival of Dionysius was established in Athens, and plays were made there to honor the gods in 600 B.C. After the plays were finished, gifts and prizes were granted to the best play that was performed by the entertainers, who were just storytellers at this period In 530 B.C., the main entertainer was added to the chorale get-together. This is likewise whenever an entertainer first is in front of an audience as a person, not as a storyteller. In 474 B.C., a second after is added by Aeschylus, the incredible playwright, and won various honors. In 468 B.C., Sophocles adds a third entertainer to the theater and composes numerous compelling plays, one being - Oedipus Rex. Entertainers likewise had an alternate name, which was "frauds." Initially, in the fifth century B.C., there was not a choice cycle for picking entertainers.

The elements of great acting are; awareness, attention, purposes, causal thinking, vibration, free body, imagination, creating affinities and complexes, events and inspiration, and psychological actions.

The evolution of acting in ancient Greek theater, acting was adapted. The huge outside venues made the difference between discourse and motion outlandish. The entertainers wore funny and grievous veils and were costumed abnormally, wearing cushioned garments and fake phalluses. In any case, there were backers of naturalistic acting even around then, and entertainers were held in high regard. In the Roman time frame, entertainers were slaves, and the degree of execution was low, wide sham being the most famous sensational structure. The misfortunes of Seneca were most likely perused in declamatory style, rather than followed up on stage. During the Christian time frame in Rome, acting practically vanished, the custom being maintained by voyaging pantomimes, performers, and aerialists who engaged at fairs. In the strict show of Medieval times, an entertainer's every motion and inflection was painstakingly assigned for execution in the chapel, and, similarly, as with the later events under the protection of the exchange organizations, the entertainers were novices. Current expert acting started in the sixteenth penny. The Italian commedia dell'arte, whose entertainers ad-libbed persuading and engaging circumstances from general blueprints. During the Reclamation time frame in Britain, Thomas Betterton and his significant other Mary were well known for their effortlessness of conveyance, as was Edward Kynaston. Their contemporaries, Charles Hart, Barton Stall, and James Quin, nonetheless, were notable for their grand, chivalrous acting, a style that became prevailing in the principal third of the eighteenth penny. During the eighteenth century. Charles Macklin and his student David Garrick presented a more naturalistic style, and comparative developments occurred in France and Germany.

References:

J. O. Hughes, 2020

The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 2012

Larque, Thomas, 2001

0 notes

Photo

Compleat Female Stage Beauty - Walking Shadow Theatre Company

In the flamboyant reign of King Charles II, London’s most renowned leading lady is a man named Edward Kynaston. But when royal decree puts women onstage and Kynaston finds his role reversed, he must learn to adapt to the times. Can England’s first actress help him become the man he never was? The battle of the sexes takes to the stage in this regional premiere by acclaimed local playwright Jeffrey Hatcher. For more information visit: https://www.walkingshadow.org/shows/compleat-female-stage-beauty/

#puzzle room minneapolis#puzzle rooms in twin cities#special events minneapolis#theater tickets minneapolis#innovation theatre minneapolis

0 notes

Text

How millions of veterans were returned to civilian work en masse after WWII

After the tip of the conflict, hundreds of thousands of servicemen and girls wanted a job. Coxy58/Shutterstock

The current authorities’s wrestle to get Britain again to work amid the pandemic appears rather less daunting when in comparison with the problem that confronted its predecessor in 1945. In her positive account of the conflict’s finish, historian Maureen Waller reminds us that in the beginning of September 1945, 4,243,000 males and 437,000 girls have been serving within the armed forces. Many have been frantic to return dwelling and their expertise have been wanted desperately.

Ernest Bevin, minister of labour within the wartime coalition, had began planning for his or her demobilisation in 1942, however his plans had assumed that conflict towards Japan would drag on after the defeat of Germany, permitting time for gradual demobilisation. As a substitute, the atomic assaults on Hiroshima and Nagasaki introduced the combating to a sudden finish. Labour’s victory within the 1945 basic election added to the strain: the get together’s manifesto had promised immense change.

Social historian David Kynaston remembers the issues dealing with the brand new authorities. Three quarters of one million houses had been destroyed or have been badly broken and far surviving housing consisted of “Victorian slums within the main cities and huge pockets of overcrowded, inadequate-to-wretched housing nearly in all places”. Nationwide debt had ballooned to £3.5 billion.

With Bevin promoted to overseas secretary, his successor at Labour and Nationwide Service was the veteran trades unionist George Isaacs. In September 1945, Isaacs represented the federal government on the Trades Union Congress (TUC) convention in Blackpool. My very own analysis in historic newspaper archives reveals the temper of delegates assembly there.

Manpower key to reconstruction

The Manchester Guardian gave intensive protection to a speech by the previous miner, now TUC President Ebby Edwards on September 11 1945. Edwards insisted that manpower was the important thing to reconstruction. On VE Day, civilian industries employed Four million fewer employees than in 1939. Edwards warned that “if the federal government is so ill-advised as to try to carry males within the nationwide forces indefinitely, there might be grave hazard of a repetition of the incidents that marked demobilisation on the finish of the final conflict”.

The demobilisation scheme devised in 1917 meant that males who had served longest have been typically the final to be demobilised. This provoked mutinies at British military camps in Calais and Folkestone and an indication by 3,000 troopers in central London.

Clement Attlee turned Labour prime minister in July 1945.

Wikipedia

The Manchester Guardian reported that Clement Attlee, who turned the Labour prime minister in July 1945, was acutely conscious that demobilisation in 1945 should be fairer and quicker. Attlee estimated that to get business and providers working once more “a rise of about 5 million employees was required”. He stated his authorities was decided “to do justice between all those that have been serving and specifically to these serving abroad”.

The Occasions, nonetheless, in 1945 an elite, institution broadsheet, was not an instinctive cheerleader for Attlee’s proudly socialist authorities. On September 14 1945 its editorial regretted the absence of “detailed details about many necessary features of demobilization coverage”.

The Occasions conceded that: “For the reason that ultimate give up in South-East Asia occurred so not too long ago … Ministers could fairly ask for a number of weeks extra to finish their plans.” Nevertheless, Britons would “count on an early instalment of the dashing up of which, because the Prime Minister has stated, the demobilization plan is succesful”.

The Economist, a weekly political publication learn by opinion formers, took the view that Bevin’s unique plan for demobilisation was primarily based on sound ideas. He had recognised that those that had served longest ought to be launched from the armed providers first. His scheme gave precedence to housebuilders who had urgently wanted expertise. Nevertheless, The Economist sought a rebalancing of army and civilian energy. “As a substitute of the service departments telling the civilians what number of they will launch,” it declared on September 15, “the civilians ought to inform the army what number of they could preserve”. Pace was important.

For troopers, sailors and airmen who had been overseas for years, no return date might be too early. If right this moment’s authorities is grappling with a desperately advanced balancing of threat and reward, their predecessors confronted an equally pressing need for the fairer world Labour had promised its voters. A couple of not less than have been already displaying their impatience in letters to the fiercely pro-government Every day Mirror, which remained decided to signify “the strange bloke in all three providers” and to voice “the grumbles and grievances of the personal, the score and the erk” (slang for an aircraftsman of the bottom rank within the Royal Air Power).

No politician underneath such strain may fail to really feel gratitude in direction of a loyalist of RAF man and Mirror reader I.A.C. Guthrie’s calibre. In his letter, printed within the Mirror on September 24 1945, Guthrie defended the demobilisation scheme towards “Irresponsible statements by public nonentities” who had satisfied “numbers of servicemen that they’re receiving a uncooked deal over demobbing”. This was unfair to Attlee’s new administration he defined, including: “Solely an irresponsible authorities would have tried to impress by a ‘lighting demob’ that might have executed irretrievable hurt to the nation.”

At the moment such tribal loyalty is most incessantly expressed not in newspapers however through social media, and never all the time in such well mannered English. Seventy-five years in the past, this disaster ended fairly effectively for Labour. Waller information that Attlee’s authorities demobilised a 3rd of the armed forces by Christmas 1945 and the remainder by Easter 1946.

Tim Luckhurst has obtained analysis funding from Information UK and Eire Ltd. He’s a member of the Society of Editors and the Free Speech Union. This text relies on analysis for his present work in progress, a guide for Bloomsbury Educational underneath the provisional title Reporting the Second World Warfare. Newspapers and the Public in Wartime Britain

from Growth News https://growthnews.in/how-millions-of-veterans-were-returned-to-civilian-work-en-masse-after-wwii/

via https://growthnews.in

0 notes

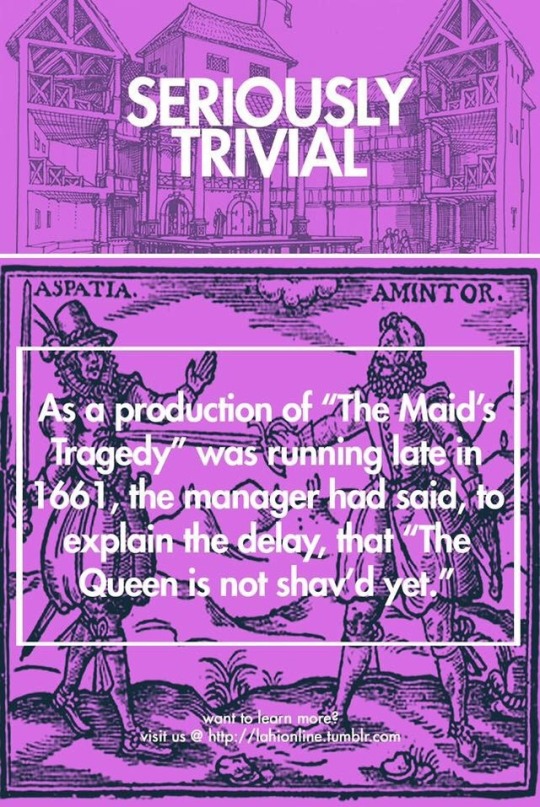

Photo

LaHi presents: Seriously Trivial As a production of “The Maid’s Tragedy” was running late in 1661, the manager had said, to explain the delay, that “The Queen is not shav’d yet.” During the Monarchy Restoration, women started to play female roles in the theatre. One of the last males to take on female roles was Edward Kynaston, who took on the role as The Queen in “The Maid’s Tragedy” in 1661, King Charles II had come earlier than expected to a show of the play, and he began to get impatient as to why the play wasn’t starting yet. The manager, who thought that honesty was the best policy, explained to his majesty that “the Queen is not shav’d yet.” Sources: Crofton, Ian. History without the boring bits. London, Quercus, 2015. Haggerty, G. E. "“The Queen was not shav’d yet”: Edward Kynaston and the Regendering of the Restoration Stage." The Eighteenth Century, vol. 50 no. 4, 2009, pp. 309-326. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/ecy.0.0045 Poster by Nic Calilung

1 note

·

View note

Link

For just $3.99 The Case of Mrs. Loring Released on July 15, 1958: In a landmark legal case a British court is asked to define adultery in a very new way. Directed by: Don Chaffey Written by: Dan Sutherland with screenplay by Anne Edwards and Denis Freeman The Actors: Julie London Mary Loring, Anthony Steel Mark Loring, Basil Sydney Sir John Loring, Donald Houston Mr. Jacobus, Anton Diffring Carl Dieter, Andrew Cruickshank Doctor Cameron, Frank Thring Mr. Stanley, prosecuting counsel, Conrad Phillips Mario Fiorenza, Kynaston Reeves the judge, Mary Mackenzie nurse Parsons, Georgina Cookson Mrs. Duncan, John Rae jury foreman, Michael Logan court usher, Trevor Reid reporter, John Charlesworth club reporter, Michael Anthony newspaperman, Van Boolen peasant, Max Brimmell Spanish photographer, Rodney Burke barrister, John Fabian barrister, Trader Faulkner flamenco dancer, Stewart Guidotti unknown Runtime: 1h 26m *** This item will be supplied on a quality disc and will be sent in a sleeve that is designed for posting CD's DVDs *** This item will be sent by 1st class post for quick delivery. Should you not receive your item within 12 working days of making payment, please contact us as it is unusual for any item to take this long to be delivered. Note: All my products are either my own work, licensed to me directly or supplied to me under a GPL/GNU License. No Trademarks, copyrights or rules have been violated by this item. This product complies withs rules on compilations, international media and downloadable media. All items are supplied on CD or DVD.

0 notes

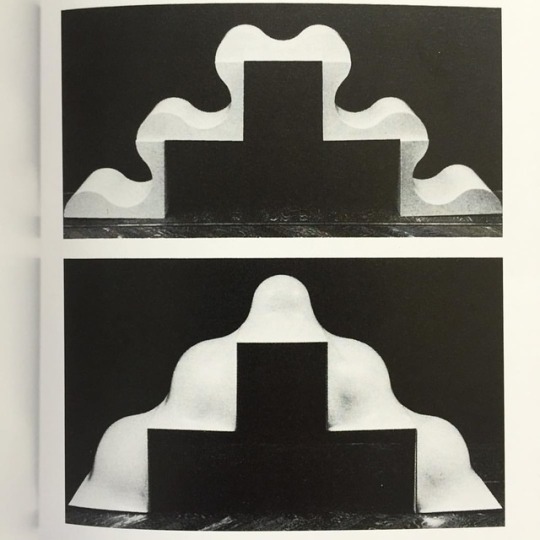

Photo

NEW IN THE BOOKSHOP: OTHER PRIMARY STRUCTURES (2013) The landmark Jewish Museum exhibition Primary Structures offered the first presentation of Minimalist sculptures in the United States, in 1966. The accompanying catalogue by Kynaston McShine became a key resource on artists such as Donald Judd, Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, and Sol LeWitt, who were virtually unknown at the time. Other Primary Structures is a long-overdue reintroduction of this classic, out-of-print text. This two-volume set includes a replica of the original catalogue, plus a new companion volume by Jens Hoffmann that offers a global survey of early Minimalist sculpture during the 1960s and 1970s, featuring important sculptors from Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Eastern Europe, and complementing the earlier catalogue’s focus on American and British artists. Beautifully designed, this publication comes enclosed in a clear jacket that pays homage to the original catalogue’s iconic cover. Other Primary Structures is invaluable for the study of modern art history and provides an authoritative survey of Minimalist sculpture in the 1960s. Artists: Carl Andre, Lyman Kipp, Tim Scott, Richard Van Buren, Isaac Witkin, Tony DeLap, Tom Doyle, Richard Artschwager, Michael Bolus, Paul Frazier, Douglas Huebler, John McCracken, Peter Phillips, Anne Truitt, Ronald Bladen, Robert Grosvenor, Donald Judd, Robert Morris, Larry Bell, Walter de Maria, Sol LeWitt, Daniel Gorski, David Gray, David Hall, Phillip King, John McCracken, Peter Pinchbeck, Michael Todd, Derrick Woodham, Rasheed Araeen, Sérgio Camargo, Willys de Castro, Saloua Raouda Choucair, Lygia Clark, Noemí Escandell, Gego, Stanislav Kolíbal, Edward Krasiński, David Lamelas, David Medalla, Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Pape, Alejandro Puente, Norberto Puzzolo, Branko Vlahović, Oscar Bony, Benni Efrat, Yoshida Katsurō, Stanislav Kolíbal, Susumu Koshimiz, Ivan Kožarić, David Lamelas, Amir Nour, Juan Pablo Renzi, Nobuo Sekine, Antonieta Sosa, Kishio Suga, Jirō Takamatsu, Lee Ufan Available via our website and in the bookshop. #worldfoodbooks #primarystructures #otherprimarystructures #williamtucker (at WORLD FOOD BOOKS)

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

Rural Derry, 1981. The Carney farmhouse is a hive of activity with preparations for the annual harvest. A day of hard work on the land and a traditional night of feasting and celebrations lie ahead. But this year they will be interrupted by a visitor.

The new company performing in Jez Butterworth’s The Ferryman includes Owen McDonnell (Single-Handed, RTÉ/ ITV; Paula, BBC) playing Quinn Carney, Rosalie Craig (As You Like It, The Threepenny Opera, The Light Princess and London Road, National Theatre) in the role of Caitlin Carney and Justin Edwards (The Thick of It, BBC; The Man Who Invented Christmas; The Death Of Stalin) as Tom Kettle.

Further new cast members include Dean Ashton as Frank Magennis, Declan Conlon as Muldoon, Kevin Creedon as JJ Carney, Sean Delaney as Michael Carney, Saoirse-Monica Jackson as Shena Carney, Terence Keeley as Diarmaid Corcoran, Laurie Kynaston as Oisin Carney, Stella McCusker as Aunt Maggie Far Away, Francis Mezza as Shane Corcoran and Siân Thomas as Aunt Pat.

Catherine McCormack continues in her role as Mary Carney, along with Charles Dale as Father Horrigan, Mark Lambert as Uncle Pat and Glenn Speers as Lawrence Malone. As previously the full company comprises 37 performers: 17 main adults, 7 covers, 12 children on rota and 1 baby.

The Ferryman, directed by Sam Mendes, is currently booking at the Gielgud Theatre until 19 May 2018. The production won widespread critical acclaim when it opened at the Royal Court and was the fastest selling show in the theatre’s history. This phenomenal success has continued at the Gielgud Theatre where it has been playing to sold-out houses, with early morning queues on Shaftesbury Avenue for the £12 day seats each day. The production received four nominations at the annual London Evening Standard Theatre Awards, winning three honours for Best Play (Jez Butterworth), Best Director (Sam Mendes) and the Emerging Talent Award (Tom Glynn-Carney).

The Ferryman is directed by Sam Mendes, designed by Rob Howell, lighting by Peter Mumford, sound and original music by Nick Powell, with the new cast directed by Tim Hoare and casting by Amy Ball CDG.

[See image gallery at www.londontheatre1.com]

Listings:

Sonia Friedman Productions, Neal Street Productions

& Royal Court Theatre Productions present

The Ferryman

By Jez Butterworth

Directed by Sam Mendes

Designer Rob Howell

Lighting Designer Peter Mumford

Composer & Sound Design Nick Powell

Gielgud Theatre

Shaftesbury Ave, Soho, London W1D 6AR

20 June 2017 – 19th May 2018

New cast members for The Ferryman at the Gielgud Theatre

Interview with Conor MacNeill from the cast of The Ferryman

The Ferryman London Gielgud Theatre Transfer

http://ift.tt/2lncf92 London Theatre 1

0 notes

Quote

Tom and I and my wife to the Theatre and there saw The Silent Woman, the first time that ever I did see it and it an excellent play. Among other things here, Kynaston, the boy, hath the good turn to appear in three shapes: (1), as a poor woman in ordinary clothes to please Morose; then in fine clothes as a gallant, and in them was clearly the prettiest woman in the whole house – and lastly, as a man; and then likewise did appear the handsomest man in the house.

from samuel pepys’s 7 january 1661 diary entry on seeing edward kynaston perform in epicene, or the silent woman by ben jonson

27 notes

·

View notes