#gwerful mechain

Text

Should really do my job as an MA student and post on here about Welsh poets nobody knows because there are so many bangers out there!!!

#the technique!! the imagery!!#also i want everyone to know about gwerful mechain because what that woman wrote everyone should know#and dafydd ap gwilym is the welsh equivalent of petrarch!!#but (no offence to petrarch) actually cool!!

1 note

·

View note

Text

berth addwyn, Duw'n borth iddo

Let's all take a moment for one of the best last lines of Welsh medieval poetry (actually any poetry anytime) thanks to Gwerful Mechain

Her poem Cywydd y Cerdor, basically a diss track to all the other bards at the time who didn't even dare. Quality stuff, babe.

"lovely bush, God save it"

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

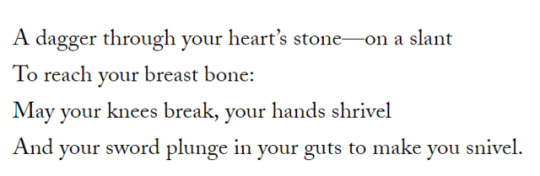

“To Her Husband for Beating Her” - Gwerful Mechain

Through your heart’s lining let there be pressed—slanting down—

A dagger to the bone in your chest.

Your knee crushed, your hand smashed, may the rest

Be gutted by the sword you possessed.

Translated from the Middle Welsh by A.M. Juster

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gwerfyl Mechain

Bardd o Gymraes o Bowys a ganai yn ail hanner y 15fed ganrif oedd Gwerful Mechain neu Gwerful ferch Hywel Fychan (fl. c. 1460 - wedi 1502?). Y brydyddes o Fechain. Mae hi'n enwog am ei cherddi erotig beiddgar - sy'n enghreifftiau rhagorol o ganu maswedd Cymraeg yr Oesoedd Canol - ac yn perthyn i ddosbarth prin o feirdd benywaidd yn Ewrop yr Oesoedd Canol. Fel mae ei henw yn ei awgrymu, brodores o ardal Mechain ym Mhowys oedd Gwerful. Ychydig iawn o wybodaeth sydd ar gael amdani, ar wahân i dystiolaeth ei cherddi. Roedd hi'n ferch i Hywel Fychan a'i wraig Gwenhwyfar ferch Dafydd Llwyd. Roedd ei gor-hendaid Madog ab Einion yn uchelwr pwysig ym Mechain. Roedd ei thad, Hywel Fychan, yn byw yng nghwmwd Mechain Is Coed. Priododd Gwerful John ap Llywelyn Fychan a chafodd ddwy ferch o'r un enw ganddo (neu un ferch), sef Mawd. Yn ôl un traddodiad, roedd hi'n cadw tafarn. Cyfnod y beirdd; canu masweddol/masweddus.

Gwerful Mechain (1460–1502), is the only female medieval Welsh poet from whom a substantial body of work is known to have survived. She is known for her erotic poetry, in which she praised the vagina among other things. For medieval Europeans, talking openly about sex in what we might think of now as explicit detail was a very normal part of life. Although life in medieval Wales was hard, and both men and women were encouraged by the church to keep their lusts carefully contained for the sake of childbearing alone, Gwerful Mechain’s unbridled enjoyment of sex and her own body demonstrates the happiness and pleasure to be found in the simple act of physical love. Although less well known, Gwerful Mechain’s devout poetry on religious themes shows her acceptance of religious teachings.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“To her husband for beating her”, by Gwerful Mechain [1460-1502].

Translation from Welsh by Katie Gramich.

#welsh#poetry#wales#middle ages#gwerful mechain#badass women#feminism#domestic violence for ts#you tell them gwerful#i highly suggest clicking on the link btw#there are more delightful poems

59 notes

·

View notes

Link

An article on 4 women poets to read more by and about! (Gwerful Mechain, Katherine Philips, Cranogwen and Lynette Roberts.)

Gwerful Mechain was a medieval poet who wrote an ode to female genitals and poetry against domestic abuse; Katherine Philips was a 17th century poet who set up a ‘Society of Friendship’ in Cardigan, and wrote poetry to women, as well as a poem that was critical of marriage when she was 16 (not long before she married) and Cranogwen (Sarah Jane Rees) also wrote poetry to women and an Eisteddfod-winning poem that was critical of marriage and domestic abuse.

#link#ariticle#poetry#queer poetry#queer literature#queer history#lgbt history#women's history#welsh queer history#gwerful mechain#katherine philips#cranogwen#sarah jane rees#lynette roberts#m#Idk as much about lynette roberts but seems she's been quite forgotten so definitely someone to read more of!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alright guys, opening this up to the floor. What’s the earliest known poem against domestic violence, in any language? I ask because I was reminded of the incandescent brilliance that is Gwerful Mechain today - a female bard from Wales who lived some time about the 1400s mark. She is brilliant for at least 800 reasons, but crucially here, she wrote this:

Dager drwy goler dy galon - ar ogso

I asgwrn dy ddwyfron;

Dy lina dyr, dy law’n don,

A’th gleddau i’th goluddion.

Impossible to translate and keep just how beautiful that sounds in Welsh, but it roughly means:

(Let there be) a dagger pressed to the lining of your heart - slanting down

To the bone in your chest;

(Let) Your knee (be) broken, your hand crushed,

And the sword (you possessed) gut (the rest of you).

It’s called I’w Gŵr Am Ei Churo, or To Her Husband for Beating Her. It’s from the early 1400s some time.

Are there any earlier that we know of?

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

8

I’ve never entirely understood why magicians use bad second-hand poetry when they could use first class second-hand poetry or write their own shitty poetry. Admittedly, there are more examples of the latter than the former (see: Andrew Chumbley). The assumption often seems to be that if it’s old then it’s good, but that is patently un-true. If millions of dead people prove the validity of a thing then we would still be saying that leukaemia is un-treatable 1.

Most living traditions produce new material. Capoeira has a wealth of old songs, but young capoeiristas still write new ones. An inspired song has as much (or more) power as an inherited one. It’s all about what the words are imbued with. I doubt that there is much traditional poetry in Chumbley’s work. The core material may come from an older tradition, but the voice is too consistent across his published work for it to come from other sources. He either created it whole cloth or he gussied it up. People find it potent nevertheless.

The bones of the work and what it is intended to mete are more important. In Britain poets held the power to kill or maim with satire alone. That is a tradition that continued well into the Christian era. As an example, see this Welsh englyn attributed to Gwerful Mechain (c. 1460-1502, trans. Katie Gramich), which calls on no god or power beyond the poetic form:

I’w gwr am ei churo

Dager drwy goler dy gallon – ar osgo

I asgwrn dy ddwyfron;

Dy lin a dyr, dy law’n don

A’th gleddau I’th goluddion

To her husband for beating her

A dagger through your heart’s stone - on a slant

To reach your breast bone;

May your knees break, your hands shrivel

And your sword plunge in your guts to make you snivel

(I am making a few assumptions here and skipping over the importance of the poetic form used, but I wanted to reference Gwerful. Also - if you compare the internal meter of the original englyn to the translation you can see that Gwerful was a much better poet than her translator, but there’s not much one can do about that short of learning old Welsh)

I see some useful bone structure in the Headless Rite. The formula for invocation is clear just underneath its skin. Aiden Wachter uses a similar progression in Six Ways: State intention, call in the power required, identify the desirable traits of that power, then acquire or borrow them as one’s own (p.18). However, although the stated intention of the Rite in the Greek Magical Papyri (PGM) is for exorcism it plainly has a more complex application.

Previously I’ve touched on parallels between the Headless Rite and the Song of Amergin. The main things I identify as being different between them are that 1) the Song calls up Eire, whereas the Rite calls on a(n unknown) god/s. 2) The Song dispenses with a lot of the early stages and proceeds directly to identifying with the land. Arguably that may be due to editorial interference, but personal experience indicates that those stages are not necessary. Especially if a relationship already exists.

A lot of people use the Headless Rite, or its Thelemic equivalent, as part of a daily practice. I’ve read they do this because the Rite confers dominance over spirits and may align the magician with a particular current. Certainly it has been used to augment a variety of other practices, particularly deity obsession (Stratton-Kent). The flexibility of the formula is confirmed by the Song, in my mind. I suspect that it’s far older than the Headless Rite’s stated purpose in the PGM.

I see the sense of using praise or boast poetry as a daily practice. However is it necessary, or even desirable, to use such a dramatic martial formula every day unless you have regular goetic practice? To bombastically acclaim one’s dominance on a daily basis? It’s a bit like a yuppie in the 1980s yelling, ‘You’re a TIGER!’ at the mirror every morning.

As I think about using this as part of a daily practice I ask what purpose it should serve. Let’s say I want it to align me with a particular current of being, re-affirm who/what I am and build a core strength for later dealing with spirits. Fine. The Headless Rite would align me with an unknown deity or deities (at minimum it seems to reference Osiris and Yahweh) through use of some barbarous names we no longer remember the origin, meaning or use of. That doesn’t really suit.

I could adapt the Headless Rite. I am tempted to adapt it for use alongside kaula/tantra. It would be fun making the syncretism work. However that’s something I’ll probably come back to because right now I don’t want to focus on deities and spirits. I want to strengthen myself and my practice.

So I went back to thinking about other work that exists in the same realm. Work that could support a useful trance and be imbued with the same principles I work with. I thought for a long time. I considered Sufi verses and other options, but I kept coming back to Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass.

I have used Whitman’s poetry in a similar way to the Song of Amergin before. In particular I’ve used I sing the body electric. It works if used with a correct method. Whitman’s poetry also has a broader scope than either the Rite or Song of Amergin. In Song of Myself he is singing up an ecstatic vision of what we could be, what he sees that we are underneath the eidolons that clothe us. It’s a much better fit for what I am and how my magic is arrayed. It also fits the formula for invocation.

In fact, Leaves of Grass is interesting beyond invocation. When Chumbley wrote Azoetia and Dragon Book of Essex he tried to create a living grimoire – something bigger than its pages. Whitman did the same, but, I think, more successfully from an ecstatic point of view. Leaves of Grass opens by defining Whitman’s intention (“One’s self I sing”), then by charging the book with its purpose (“Then falter not, O book, to fulfil your destiny”). He casts aside materialism in EIDOLONS, summons up and addresses his audience with the purposes he tasks them with, and, in SHUT NOT YOUR DOORS, he opens the gates for the book to do its work. Walt Whitman may not have written Leaves of Grass to be a work of magic, but because it is structured like an inspired text it can act as one nevertheless.

The content of Song of Myself invokes some very particular states. Take 43:

“I do not despise you priests, all time, the world over,

My faith is the greatest of faiths and the least of faiths,

Enclosing worship ancient and modern and all between ancient and modern…

Ranting and frothing in my insane crisis or waiting dead-like til my spirit arouses me,

Looking forth on pavement and land, or outside of pavement and land,

Belonging to the winders of the circuit of circuits.”

Or 48,

“I have said that the soul is not more than the body,

And I have said that the body is not more than the soul,

And nothing, not God, is greater to one that one’s self is”

Or 41,

“Magnifying and applying come I,

Outbidding at the start the old cautious hucksters,

Taking myself the exact dimensions of Jehovah,

Lithographing Kronos, Zeus his son, and Hercules his grandson,

Buying drafts of Osiris, Isis, Belus, Brahma, Buddha,

In my portfolio placing Manito loose, Allah on a lead, the crucifix engraved,

With Odin and the hideous faced Mexitli and every idol and image,

Taking them all for what they are worth and not a cent more”

To me, that is bold magic and better suited to daily practice where one is building relationships and one’s own self.

The main problem with Song of Myself is that it is bloody long. However it’s broken into 52 sub-sections. That allows for using the poetry flexibly as a more reflective and prolonged invocationary practice. Whitman’s use of (sort of) free verse also allows editing to focus on sections that fit what is desired. Consider – charging a pentacle can be done (in part) through choosing sections of Bible verse that help evoke a particular quality. Something similar can be done here with invocation. Whitman wrote Leaves of Grass to inspire and to inform an alternative way of being in the world. This is entirely appropriate to its purpose.

I’ve gone on long enough, so I won’t get into the pros and cons of adapting supportive aspects of the Headless Rite like the barbarous names and paper crown.

1 Read The Emperor of all Maladies by Siddhartha Mukherjee

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

GOD`S SACRED ACRE

Gwerful Mechain was a late medieval Welsh poet (circa 1460-1502) with a gleefully crude, rude and raucously lude attitude to life. She took no prisoners and perhaps expected nothing in return save a laugh or two at her annihilating language of sex.

For most of the time since she lived and breathed, a malecentric society had suppressed and hidden this genius away from the public gaze because of…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The Female Genitals - Gwerful Mechain

Every foolish drunken poet,

boorish vanity without ceasing,

(never may I warrant it,

I of great noble stock,)

has always declaimed fruitless praise

in song of the girls of the lands

all day long, certain gift,

most incompletely, by God the Father:

praising the hair, gown of fine love,

and every such living girl,

and lower down praising merrily

the brows above the eyes;

praising also, lovely shape,

the smoothness of the soft breasts,

and the beauty's arms, bright drape,

she deserved honour, and the girl's hands.

Then with his finest wizardry

before night he did sing,

he pays homage to God's greatness,

fruitless eulogy with his tongue:

leaving the middle without praise

and the place where children are conceived,

and the warm quim, clear excellence,

tender and fat, bright fervent broken circle,

where I loved, in perfect health,

the quim below the smock.

You are a body of boundless strength,

a faultless court of fat's plumage.

I declare, the quim is fair,

circle of broad-edged lips,

it is a valley longer than a spoon or a hand,

a ditch to hold a penis two hands long;

cunt there by the swelling arse,

song's table with its double in red.

And the bright saints, men of the church,

when they get the chance, perfect gift,

don't fail, highest blessing,

by Beuno, to give it a good feel.

For this reason, thorough rebuke,

all you proud poets,

let songs to the quim circulate

without fail to gain reward.

Sultan of an ode, it is silk,

little seam, curtain on a fine bright cunt,

flaps in a place of greeting,

the sour grove, it is full of love,

very proud forest, faultless gift,

tender frieze, fur of a fine pair of testicles,

a girl's thick grove, circle of precious greeting,

lovely bush, God save it.

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

Zenobia: Gwerful Mechain (1462-1500) was a Welsh female poet, who was famous for writing about the subjects of sex and religion (sometimes simultaneously). She is most famous for her erotic poetry, specifically, "Cywdd y Cedor/Ode to the Pubic Hair," where she praises the vulva and mocks male poets who praise the female body, but never the female genitals from where all humanity comes from.

That woman is my spirit animal! 😍❤️✨ (✿ ♥‿♥) ✨❤️😍

#history#women in history#zenobia always sends interesting asks#this is so amazing!#that woman is so me!#Anonymous#ask

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

For #internationalwomensday2018 I thought I would direct you to Gwerful Mechain. A medeival Welsh female poet who, among other things wrote an "Ode to the Pubic Hair". https://t.co/e80x62DaEh #IWD2018 https://t.co/sZuPNTY5Td

For #internationalwomensday2018 I thought I would direct you to Gwerful Mechain. A medeival Welsh female poet who, among other things wrote an "Ode to the Pubic Hair". https://t.co/e80x62DaEh #IWD2018 pic.twitter.com/sZuPNTY5Td

— Jason Evans (@WIKI_NLW) March 8, 2018

via Twitter https://twitter.com/WIKI_NLW

0 notes

Note

For the ask meme: 4, 5 or 6, and 12

4. favourite dish specific for your country?

OH HO HO that’s proper, traditional Welsh pancakes, made the proper traditional way.

So what you do is, you make a pancake batter with half wholewheat flour and a bunch of herbs, and turn that into crepes. Then you make two fillings, one cheesy-mustardy, and one leek-and-garlic (and mushrooms if you like fungus), and then you construct something a bit like a lasagne? Crepe, cheese layer, crepe, leek layer, and so on. Sprinkle with cheese, bake for 15 minutes, then cut it like a cake to serve.

It’s the fucking bomb, I tell thee. But frustrating - absolutely nowhere sells it, not even places that claim to do traditional Welsh cooking (instead they’ll do a sort of pan-Western food but the cow came from Carmarthenshire so WELSH). I do it on St Davids Day, and my husband’s birthday sometimes.

Honourable mention to Welshcakes, mind. Especially if they’re splits.

5. favourite song in your native language?

Oh Christ, so many! I mean, I don’t think it’s possible to go through a list like this without mentioning Sebona Fi by Yws Gwynedd, which is a fucking BANGER that forces you to be happy, even though the chorus is like WE’LL ALL BE DIRT IN THE END

Um, most things by y Bandana. So hard to narrow it down. Maybe Geiban? Or Wyt Ti’n Nabod Mr Pei? Or, ooh, I know - Be’ Nawn Ni.

Oh, oh god but also there’s Llwytha’r Gwn by Candelas and Alys Williams, that’s a fucking tune. And Fi Fi Fi by Meinir Gwilym... WAIT and also Llatai by Fernhill.

Hmm. One of them.

6. most hated song in your native language?

Lol, most things. The worst thing that ever happened to Welsh language music, after the cultural purges by the Welsh Non-Conformists (and the English I guess), was the fucking 80s. Everything was synth for about three decades afterwards. We’ve barely recovered now. Shocking.

Possibly just because of how much everyone else seems to love it when it’s fuck-awful, though, I’m going Ceidwad y Goleudy by Bryn Fon. Jesus Christ.

12. what do you think about English translations of your favourite native prose/poem?

Haha, oh, they tried, and it’s not their fault.

Trouble is, Welsh poetry is written in cynghanedd, an incredibly complex form of verse that the language was built to accommodate (other languages construct their poetry to suit the language instead, but these languages are Cowards.) And English literally cannot do it. You can sort of manage it, but only if you sacrifice meaning and put pretty words together, and even then, it just can’t quite manage Cynghanedd Groes, the most complex lines of all. But this means that no translation can ever capture the effect. Not even close. The lyrical beauty of it that makes you weep down to your soul is gone.

And that’s a shame, because my favourite poem is Cywydd y Cedor by Gwerful Mechain, a female bard in the fourteenth century, and it basically means Ode to the Vulva.

It’s fucking filth, written in that hauntingly beautiful poetic verse, and it is Impossible to convey its full glory in English. Not even close. Can’t be done.

It’s so good tho, even in English. Ya’ll should read it.

Thanks for the questions! This was fun.

40 notes

·

View notes