#lucius aelius caesar

Text

Lucius Aelius Caesar, intended heir to Hadrian. Born Lucius Ceionius Commodus on 13 January 101 CE, he was abruptly adopted by Hadrian in 136, after a near-fatal hemorrhage convinced the emperor that a designated successor was needed. (The move angered two men who had thought themselves in line for the position, Hadrian's brother-in-law Servianus and his grandson Fuscus Salinator. Claims of a planned coup circulated, and Hadrian had both men executed, which cast a dark cloud over the last years of his reign.) Lucius Aelius himself was in poor health and predeceased Hadrian on 1 January 138. In his stead, Hadrian adopted the future Antoninus Pius and compelled Antoninus in turn to adopt two heirs: the future Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Aelius' son, the future Lucius Verus.

Portrait bust by an unknown artist, 2nd century CE. Now in the Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence. Photo credit: Carole Raddato.

#classics#tagamemnon#Ancient Rome#Roman Empire#ancient history#Roman history#Lucius Aelius Caesar#art#art history#ancient art#Roman art#Ancient Roman art#Roman Imperial art#sculpture#portrait sculpture#portrait bust#Uffizi#Uffizi Gallery#Galleria degli Uffizi

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

A ROMAN MARBLE PORTRAIT BUST OF THE EMPEROR LUCIUS VERUS

ANTONINE PERIOD, LATE 2ND CENTURY A.D.

Lucius Aurelius Verus (15 December 130 – January/February 169) was Roman emperor from 161 until his death in 169, alongside his adoptive brother Marcus Aurelius. He was a member of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty. Verus' succession together with Marcus Aurelius marked the first time that the Roman Empire was ruled by more than one emperor simultaneously, an increasingly common occurrence in the later history of the Empire.

Born on 15 December 130, he was the eldest son of Lucius Aelius Caesar, first adopted son and heir to Hadrian. Raised and educated in Rome, he held several political offices prior to taking the throne. After his biological father's death in 138, he was adopted by Antoninus Pius, who was himself adopted by Hadrian. Hadrian died later that year, and Antoninus Pius succeeded to the throne. Antoninus Pius would rule the empire until 161, when he died, and was succeeded by Marcus Aurelius, who later raised his adoptive brother Verus to co-emperor.

As emperor, the majority of his reign was occupied by his direction of the war with Parthia which ended in Roman victory and some territorial gains. In the spring of 168 war broke out in the Danubian border when the Marcomanni invaded the Roman territory. This war would last until 180, but Verus did not see the end of it. In 168, as Verus and Marcus Aurelius returned to Rome from the field, Verus fell ill with symptoms attributed to food poisoning, dying after a few days (169). However, scholars believe that Verus may have been a victim of smallpox, as he died during a widespread epidemic known as the Antonine Plague.

Despite the minor differences between them, Marcus Aurelius grieved the loss of his adoptive brother. He accompanied the body to Rome, where he offered games to honour his memory. After the funeral, the senate declared Verus divine to be worshipped as Divus Verus.

#A ROMAN MARBLE PORTRAIT BUST OF THE EMPEROR LUCIUS VERUS#ANTONINE PERIOD#LATE 2ND CENTURY A.D.#marble#marble bust#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient rome#roman history#roman empire#roman emperors#roman art

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

sejanus plinth: the name & what it says about fate vs. choice

sejanus plinth is the namesake of the roman solider, lucius aelius sejanus. i've seen many people question why suzanne collins would choose to name sejanus plinth after this historical figure, and i think her reasoning was rather clever. their similarities are few, but striking: both of them have fathers name strabo, both came from humble riches and both of them were eventually tried for treason. save for that, it seems everything about their narratives were different. i believe collins did this as a way to invite conversation surrounding the topic of destiny vs. choice.

like sejanus plinth, lucius aelius sejanus was born into opportunity because of his father, lucius seius strabo. the roman sejanus was born into the equestrian class, which was one of two upper classes in roman republic. the other class was the patricians. the equestrian class were beneath the patricians (much like how district two, while wealthy, was still seen as below the capital). lucius seius strabo distinguished himself by entering not one, but two, of the highest ranking positions that could be afforded to people in his class: the governor of egypt & praetorian prefect (the praetorian guard was, essentially, a unit of the roman army meant to bodyguard the emperor and their family, as well as watching over civilians). while there is much to be said about the parallels between the equestrian class and district 2--and how both worked to protect the higher class, while remaining nonthreatening to them-- that is a post for a later day.

unlike sejanus plinth, the roman sejanus grasped readily onto the opportunities his father, strabo, had gotten for him. on the back of his father's hard work, roman sejanus rose to power in the praetorian guard, eventually becoming one of the praetorian prefects, alongside his father. this is where the narratives of sejanus plinth and lucius aelius sejanus begin to greatly divide. though sejanus plinth had been readied to take over his father's empire from a young age (being taught how to shoot guns, being the sole heir), he did not take readily to the idea, especially when they were transferred to the capital. sejanus plinth did not see what was happening the capital as desirable, whereas lucius aelius sejanus found himself increasingly power hungry and he did wish to increase his ranking. eventually the roman sejanus outdid his father in his accomplishments. he gained the trust of the emperor tiberius and rose to the position of praetor--a ranking not usual for someone of his class background. this earned him enemies amongst the patrician class and the imperial family, with one of them being drusus julius caesar, the very son of emperor tiberius himself. drusus did not like sejanus because he was encroaching on his grounds, seemingly taking his position as his father's successor in everything but name. sejanus even went as far as trying to secure these ties by marrying his four year old daughter to one of tiberius' family members, but couldn't because the boy died. however, sejanus' ambition did not let him stop there. eventually he poisoned drusus slowly after seducing his wife and making a conspirator out of her. the slow nature of the death allowed it to be ruled natural causes.

in the end, roman sejanus was tried for treason when tiberius began to grow suspicious of sejanus and his growing influence. whlle sejanus plinth shares the same end as this sejanus, the nature of their downfalls cannot be more differerent. sejanus plinth was tried for treason, yes, but hardly for his growing influence, and certainly not for his desire for power. sejanus plinth was hung because of what the capital deemed rebel conspiracy. but plinth died, not because he wished to be powerful, but because he wanted the districts to be free. while sejanus plinth might've been destined to his beginning and fated to his ending, he made choices along the way that drove him away from the path that his predecessor took. he continually chose empathy and kindness, and he could not find comfort in his father's successes and his riches, knowing how many were being punished for n good reason.

the differences between sejanus plinth and lucius aelius sejanus are just as important as their similarities -- if not more -- because they bring up a conversation suzanne collins flirts with a lot in the ballad of songbirds & snakes, which is: how much of who we become is pre-decided and how much of it is choice? with sejanus, we see him rebelling every step of the way, even, it seems, in terms of his 'fate.' had he done what he'd been meant to do, sejanus might very well have lead a long and prosperous career alongside coriolanus or someone like coriolanus, rising to power despite the fact that the power and position was never meant for someone like him. he might've died the very same way, sure, but he'd be remembered a whole lot differently.

sejanus plinth, unlike coriolanus snow, knew that choice was important -- he knew that, though there are factors that certainly help pre-decide what we become, they are not the end all, be all. sejanus plinth's namesake was power hungry and ambitious, ready to take all that could be given to him and rise in the ranks no matter the costs, whereas sejanus plinth was kind-hearted and had no interest whatsoever in being powerful. all he wanted was justice and peace, and for people to stop killing children. they both died because someone feared they could be too powerful, but they were incredibly different people.

#sejanus plinth#hunger games#the hunger games#coriolanus snow#the hunger games analysis#the ballad of songbirds and snakes#suzanne collins#i worked so hard on this lmao

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

List of favourite Roman Emperors in ascending order

5. Marcus Aurelius:

Gaslit himself into not getting mad in his diary

4. Didius Julianus:

#1 Failemperor of the year 193, bought the throne at an auction, managed to fuck around in Rome for 66 days while getting clowned on by the senate and elephants, liked by approximately three people one of who was dead

3. Septimius Severus:

The "first Soldier-Emperor's" most notable act in relation to leading troops was falling off his horse. man didn't win a singular battle on his own

2. Pertinax:

successfully talked himself into a mutiny, unsuccessfully tried talking himself out of it again. the closest person he had to an heir had to pay his murderers to become emperor

Imperator Caesar Lucius Aelius Aurelius Commodus Pius Felix Augustus, Son of Marcus Aurelius, great-great-great-grandson of Nerva, Romanus Hercules, Invincible, Pacifier of the World, All-Surpasser, Most Nobly Born of all the Emperors:

Renamed Rome to Commodus City and then took new names and titles until he could eventually replace all the months with just his names. Had himself proclaimed God-Emperor.

Killed a hundred lions and bears and unknown numbers of deer, leopards and ostriches before chucking a whole cup of wine like a redbull and threatening the senate. got assassinated like a month later

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Antinous Ludovisi

"Manibus, oh, date lilia plenis!.. Purpureos spargam flores...

The lover of flowers would receive only futile funeral wreaths."

135 notes

·

View notes

Photo

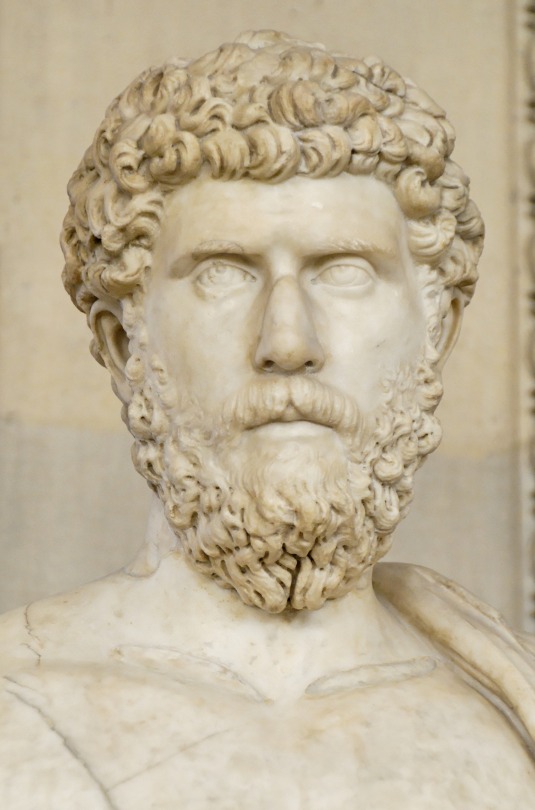

Lucius Aelius Caesar (101-137 CE)

Adopted son of Hadrian and a heir to the throne who died on the 1st of January 137 CE. His son - Lucius Verus - became emperor twenty-four years later.

Source: wikipedia, Marie-Lan Nguyen, Louvre Museum [CC BY 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5)]

#Lucius Aelius Caesar#Nerva Antonine family#prince#heir to Hadrian#ancient#Roman#art#marble#bust#Marie Lan Nguyen#Louvre

68 notes

·

View notes

Photo

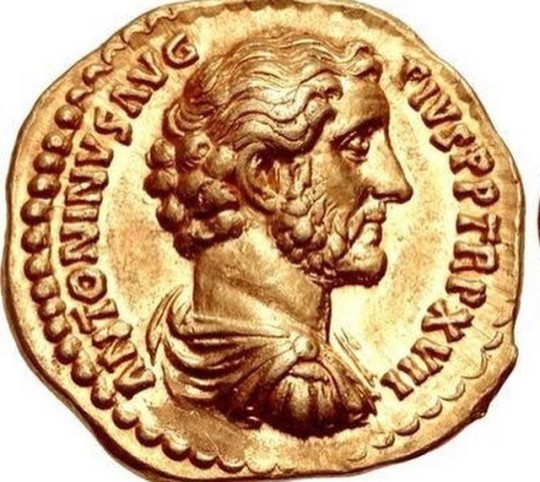

Aureus (Coin) Portraying Lucius Aelius Caesar minted in Rome, Italy, Roman Empire (AD 138)

Obverse: Lucius Aelius Caesar facing right

Inscribed: L[VCIVS] AELIVS CAESAR

Reverse: Goddess Concordia is shown seated, holding a shallow dish called a patera in her right hand as her left elbow rests on a cornucopia.

Inscribed: TRIB[VNICIA] POT[ESTAS] CO[N]S[VL] II (In exergue: CONCORD)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Father of Dragons (Emperor Commodus AU)

Summary: Eight-year-old Lucius Aelius Aurelius Commodus is enchanted by the tales of the first dragons that lived in Rome. One night, while visiting his deceased brother’s tomb, the sole heir of Emperor Marcus Aurelius witnesses those very tales being brought to life.

Word Count: 1,326

Warnings: Mentions of sibling death, some historical inaccuracy (as far as I know, there probably were not real dragons in Rome. I just wanted a chance to see my favorite emperor interact with them)

For young Lucius Aelius Aurelius Commodus, mythology was more than a collection of simple bedtime stories. They were aspirational tales of divine valor for the rising emperor in him, and a fantastical escape for the playful child within him. Tired of hearing tutors drone for hours about insipid philosophy and mind-numbing mathematical theorems, the legends of brave kings, beautiful nymphs, and horrifying-yet-powerful creatures was an oasis of wonder for the eight-year-old. Whether many of those stories were actually true or not was an entirely different matter; he loved them and believed in them with unwavering faith.

"Pompeii…after the eruption of Vesuvius?"

"Yes, Highness," Servilla, governess of the young emperor of Rome, narrated to him one night. "It was said that the first dragon eggs were found at the foot of the volcano after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius had taken place."

Little Commodus sat up excitedly in bed, eager to hear more.

"There were three of them, buried beneath layers of ash and ignored for several years until the eruption. It is said that dragon eggs could be hatched in the presence of roaring flames, and can only occur with the sacrifice of human blood. The legends say the many lives lost in Pompeii was the necessary offering for the gods to bring the dragons to Earth."

"Who is the patron god of dragons, Servilla? Is it Lord Vulcan?"

"I am afraid that I do not know, Highness." She raised her veil above her head, and tucked back a curl of hair. "After the dragons had hatched, they were sold as commodities in the public markets of Pompeii. Bought by frivolous aristocrats, they were a source of entertainment while they were little creatures who spit sparks of fire. The poor believed them to be favored by the gods, perhaps even a reincarnation of the Greek hero Agamemnon. He was said to wear a blue dragon motif on his sword belt when he fought in battle, and a three-headed dragon on his breast plate."

"Was one of the dragons blue, Servilla?"

"One of them was blue-scaled, another was red-scaled, while another had black scales. When they grew up, all of Rome wanted them dead. They were too big to keep as pets, and were very quick to anger. They breathed fire among those who displeased them, and always wanted large portions of food. Sometimes," she whispered in a menacing tone and reached for the little emperor. "They would snatch young boys playing and eat them up!"

"They would never catch me!" Commodus laughed as he was being tickled. "I would not make them angry."

"After several complaints from the people of Pompeii, Caesar Caligula decided to adopt the dragons himself. He wanted to train them to be his personal weapons. In his mind, the dragons would be strong enough to destroy anyone who dared to stand up against his rule.

They were mighty and could never be killed. They were the strongest creatures in the entire empire! However, the dragons fled the mad emperor. It is unknown where the two of the dragons escaped to, but the bones of one of the dragons were found in the city of Lanuvium, near the sea. His rotting red scales became one with the sand, and his teeth disappeared to the bottom of the ocean."

"How long do dragons live?"

"They are said to be able to live for centuries, Highness. That is, if they do not die in combat."

Despite Commodus adorably protesting for more details about the legendary dragons of Pompeii, asking if they ever had any progeny, and if they ever served another emperor, Servilla gently told Commodus that it was late and a good rest was necessary. She bade him good night and blew out the candles in his chamber.

————————————————————————————————————————

"And Servilla said that Emperor Caligula tried to tame them, and they soon escaped after his assassination. Tales of their ferocity were sung in the streets - one of them escaped to Lanuvium!"

Commodus waved his hands about as he retold his governess's stories to the coffin, barely a week he'd heard them himself. It was almost customary for the young emperor to visit the crypts every so often and "talk" to his deceased loved ones as if they were really there. Commodus knelt before the tomb of his brother Annius, not caring for the dust soiling his legs. It had been barely ten days after his eighth nameday, and yet it seemed as if Fate had decided to play a trick upon him…by taking away the last remaining brother he had.

"I swear, 'tis almost as if pre-ordained by the gods! I must ask Father when we go there again - there could even be baby dragons waddling along the beaches. It would be a delight to see."

The young emperor was interrupted by the sound of his name being called, most likely by Lucilla. He murmured a silent prayer to his brother's tomb before picking up a flaming torch to find his way up the stairs. Commodus tip-toed along one hallway, only to be encountered by an intimidating marble statue of the late Emperor Antoninus Pius - Commodus's own maternal grandfather. Dismissing this pathway as a dead end, he turned around and attempted to find another way out.

Suddenly, Commodus tripped over something - he couldn't quite see it well, but it was certainly heavy - and the torch fell from his pale hands. Yet to his surprise, the fire did not seem to hurt him at all, his skin remaining unblemished in the split second when the flames brushed against his arm. No burning sensation of any kind…the fire almost felt like the water from his bath. Comforting, in a strange way.

Perplexed, he grabbed another torch from the wall of the crypt, bringing it closer to the floor. What was it that caused him to trip? It was a chest, with enigmatic engravings all over it.

"Gods…"

With one hand holding the torch and the other fiddling with the lock, Commodus boldly opened the chest. Inside were three eggs - all scaly, yet of different hues - nestled in a bed of straw. One of them was crimson red, with black tips on its scales. The middle one bore a shade of emerald and twitched at the sight of Commodus, while the right-most egg was obsidian-hued with gold tips on its scales. They all seemed to have a few cracks, as if they had already begun to hatch.

Dragon eggs could be hatched in the presence of roaring flames, Servilla told him earlier.

Without much thought, the young emperor set the eggs on fire, dousing all three of them in flames. His green eyes widened with excitement as the eggs fidgeted and the shells continued to crack. After what felt like several enchanting hours, the flames finally subsided and in the place of the eggs, there were three baby dragons surrounded by broken shells.

Commodus knelt before them, extending his left hand as the crimson-colored dragon pecked at his palm. It was almost like playing with the birds in the palace courtyard. He even let himself chuckle as they croaked and breathed little puffs of warm smoke.

"You're so beautiful," he immediately gushed out of admiration for the little beasts. "As the one who brought you to life, I promise to care for you like my own kin."

Commodus turned to the crimson one, naming it 'Marcus' after his father. With a grin, he decided to call the green dragon 'Commodiana' because it bore the same color as Commodus's own eyes. And as for the obsidian one with flakes of gold, Commodus named it 'Annius' as homage to his late brother.

"Commodus!" His elder sister Lucilla rushed down the stairs and let a shrill cry escape from her lips as soon as she saw where he was. The princess was horrified at the little beasts, immediately asking her brother what he was doing.

"They are dragons, Lucilla, and so am I."

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Plautia Urgulanilla (fl. 1st century) was the first wife of the future Roman EmperorClaudius. They married sometime around the year 9 AD when Claudius was 18 years old. According to Suetonius, Claudius divorced her in 24 on grounds of adultery by Plautia and his suspicions of her involvement in the murder of her sister-in-law Apronia.Her father was Marcus Plautius Silvanus, a general who was consul for the year 2 BC. He had been honored with a triumph.Urgulanilla was named for her grandmother, Urgulania, a close friend of the Empress Livia Drusilla.

She gave birth to a son, Claudius Drusus, whose betrothal to a daughter of Sejanusinstilled great expectations in the prefect,which were left unfulfilled when Drusus died in early childhood.Urgulanilla had a daughter, Claudia, who was born five months after her divorce from Claudius. As Claudia was widely known to be the illegitimate daughter of the freedman Boter, Claudius repudiated the child and he had her laid at Urgulanilla's doorstep. Her adopted nephew was Tiberius Plautius Silvanus Aelianus.Urgulanilla was Etruscan.A brother of Urgulanilla was made a patrician by Claudius. Tiberius Plautius Silvanus Aelianus, the adopted son of another of her brothers, became consul in 45.

Aelia Paetina or Paetina (fl. early 1st century AD) was the second wife of the Roman Emperor Claudius. Her biological father was a consul of 4 AD, Sextus Aelius Catus, while her mother is unknown.She was born into the family of the AeliiTuberones, and thus apparently descended from the consul of 11 BC, Q. Aelius Tubero. Her father may have died when she was very young, as she was raised by a relative—Praetorian Guard Prefect Lucius Seius Strabo, the biological father of her adoptive brother Lucius Aelius Sejanus, commander of the Praetorian Guard under the Emperor Tiberius.

Aelia Paetina married the future Emperor Claudius in 28 as his second wife. Their only child was their daughter Claudia Antonia, born in 30. Claudius divorced Paetina after October of 31 AD, when her adoptive brother fell from power and was murdered. According to Suetonius, Claudius divorced Paetina for slight offenses.

In 48, after the execution of Claudius’ third wife Valeria Messalina, Claudius considered marrying for the fourth time. Claudius’ freedman Tiberius Claudius Narcissussuggested to him a remarriage to Paetina, and reminded him they had a child together. Narcissus also stated that Paetina would cherish Antonia in addition to Claudia Octaviaand Britannicus, Claudius’ children with Messalina. But another freedman, Gaius Julius Callistus, was against Claudius remarrying Paetina and stated to Claudius that he divorced her before; Callistus said that remarrying Paetina would make her more arrogant. Callistus suggested Lollia Paulina, Caligula's third wife. The third freedman, Marcus Antonius Pallas, recommended Claudius' niece and Caligula's sister Agrippina the Younger, who also had a child from a previous marriage, the future Emperor Nero. Ultimately, Agrippina was chosen.Paetina's daughter Antonia was executed in 65 or 66, shortly after the death of Nero's second wife Poppaea Sabina.

Messalina Valeria, Messalina also spelled Messallina, (born before AD20—died 48), third wife of the Roman emperor Claudius, notorious for licentious behaviour and instigating murderous court intrigues. The great-granddaughter of Augustus’ssister, Octavia, on both her father’s and mother’s sides, she was married to Claudius before he became emperor (39 or 40). They had two children, Octavia (later Nero’s wife) and Britannicus. Early sources maintain that Messalina allied herself with Claudius’s freedmen secretaries to dominate the emperor and to gratify her avarice and lust. In 42, Messalina caused Claudius to condemn to death a senator, Appius Silanus, who had slighted her advances. This heightened the tension between the emperor and Senate and prepared the way for a reign of terror in which many senators were executed after they had been denounced by Messalina. When she caused the death of Claudius’s freedman secretary, Polybius, however, the other freedmen turned against her. The correspondence secretary, Narcissus, managed to have her put to death by convincing Claudius that she and her lover, the consul designate Gaius Silius, had gone through a public wedding ceremony and were plotting to seize power.

Julia Agrippina, also called Agrippina the Younger, (born AD 15—died 59), mother of the Roman emperor Nero and a powerful influence on him during the early years of his reign (54–68).Agrippina was the daughter of Germanicus Caesar and Vipsania Agrippina, sister of the emperor Gaius, or Caligula (reigned 37–41), and wife of the emperor Claudius (41–54). She was exiled in 39 for taking part in a conspiracy against Gaius but was allowed to return to Rome in 41. Her first husband, Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, was Nero’s father. She was suspected of poisoning her second husband, Passienus Crispus, in 49. She married Claudius, her uncle, that same year and induced him to adopt Nero as heir to the throne in place of his own son. She also protected Seneca and Burrus, who were to be Nero’s tutors and advisers in the early part of his reign. She received the title of Augusta.

In 54 Claudius died. It was generally suspected that he was poisoned by Agrippina. Because Nero was only 16 when he succeeded Claudius, Agrippina at first attempted to play the role of regent. Her power gradually weakened, however, as Nero came to take charge of the government. As a result of her opposition to Nero’s affair with Poppaea Sabina, the Emperor decided to murder his mother. Inviting her to Baiae, he had her set forth on the Bay of Naples in a boat designed to sink, but she swam ashore. Eventually she was put to death on Nero’s orders at her country house.

Source: Encyclopædia Britannica

#emperor claudius#claudius#AD#roman empire#perioddramaedit#history#edit#history edit#roman emperor#plautia urgulanilla#aelia paetina#valeria messalina#agripinna the younger#nero#caligula#seutonius#roman history#ancient rome#rome#ancient history#narcissus#poppaea sabina#women in history#women of history#roman women#polybius#diane kruger#viva bianca#alessandra mastronardi#anna hutchison

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since I love the Imperial Households and ocs who fit into that framework, I thought I could make a helpful post on Roman names.

(Any ideas I had about being helpful were kinda dashed when I went looking into Roman names to make sure I knew what I was talking about. As it turns out, Roman names are a bit complicated.)

The elevator pitch breakdown is this:

Names in ancient Rome generally followed the tria nomina format of praenomen + nomen + cognomen. A praenomen is a “first” or personal name. A nomen is a “last” or extended family surname (identifying one’s extended family or gens, inherited from one’s father). A cognomen is another “last” or family surname (identifying specific branches of families or stirpes, also inherited from one’s father).

Praenomina often take after existing family members or ancestors (parent, grandparent, etc.) and are rarely used alone except by family and close friends. (In fact, it was rare for Roman women to have praenomina at all in many time periods.) On another note, eldest children usually end up with their parent’s name, exact. It’s also common for siblings to have the same name. This is why we see a lot of “the elder” / “the younger” and even numerics in Roman names.

However, all of that is,,,a gross oversimplification, especially once you hit the Imperial period and where emperors are concerned. Praenomina and cognomina got mixed around a lot there. Another interesting note is that when emperors emancipated groups of people or otherwise granted them Roman citizenship, those new citizens received the emperor’s praenomen and nomen.

Now, a note on Trials of Apollo. Riordan uses the emperor’s common names, as in the ones they’re historically best known by. This is why Caligula gets called Caligula even though that’s a nickname. Commodus is best known by his cognomen, whereas Nero is best known by his praenomen. The emperors don’t seem to mind all that much, and I’d assume they’re used to all kinds of naming conventions by now. The point here is that if you do choose Roman names for your ocs, they can go by any part of their names (not just their praenomina, if they have them) or even by something else entirely.

For the record, here are the triumvirs’ full names, from Wikipedia:

Nero

Born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus

Later Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus Germanicus

Regnal name being Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus

His father’s name was Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus. Nero was later adopted by Emperor Claudius, whose full name was Tiberius Claudius Nero Germanicus and whose regnal name was Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus.

Nero did have a daughter, who died in infancy, named Claudia Augusta. (Her name being Claudia after her father’s nomen, with Augusta being an Imperial honorific title.)

Commodus

Listed with two full names: Lucius Aelius Aurelius Commodus and Marcus Aurelius Commodus Antoninus

Likewise, two regnal names: Imperator Caesar Lucius Aelius Aurelius Commodus Augustus and Imperator Caesar Marcus Aurelius Commodus Antoninus Augustus

His father’s name was Marcus Aelius Aurelius Verus Caesar, whose regnal name was Imperator Caesar Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus.

Caligula

Born Gaius Julius Caesar (after the Julius Caesar)

Regnal name being Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus

His father’s name was Germanicus Julius Caesar.

Caligula had a daughter as well, who also died in infancy, named Julia Drusilla. (Her name being Julia after her father’s nomen, and Drusilla after her aunt.)

Because it’s an interesting note on Imperial women and their lack of praenomina, his three sisters were named Julia Drusilla, Julia Agrippina, and Julia Livilla. As they all take the nomen Julia from their gens, here we see the use of additional cognomen as personal names (often after female relatives).

My point in sharing these is mostly to show that Roman names do not often fall far from the tree. (Nero’s adoption and loss of all names similar to his father’s is a good illustration of an exception.) It can also be seen that the order of names (or the positioning of a name within the tria nomina structure) sometimes shifts or swaps.

Of course, Roman naming conventions changed over time, between social classes, and among individuals. Not all three parts of the tria nomina are required. On the flipside, someone could easily have more than three names, including honorific cognomina called agnomina (usually earned by some deed). Later in history, names used in all parts of the tria nomina were adapted into a single name usage (where, for example, what was once a cognomen became someone’s only identifying name) before arriving in the modern binominal / new trinominal structure (which is how we get modern kids with the first / personal name Octavian, for example).

And, not to be forgotten, we can always simply follow the shining modern example of Margaret “Meg” McCaffrey.

This post is a shallow, fandom-oriented introduction to a fascinating topic. I won’t pretend this covers everything, nor am I trying to tell y’all what to do. I just hope this was mildly interesting and maybe even a little helpful. <3

Here are some links to basic sources, which are worth checking out if you’re interested:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_naming_conventions

http://www.vroma.org/~bmcmanus/roman_names.html

https://www.unrv.com/culture/roman-naming-practices.php

https://www.thoughtco.com/parts-of-the-roman-name-119925

#trials of apollo#toa#triumvirate holdings#toa imperials#ocs#filodox!#feel free to add any thoughts / questions#looking over this it is interesting that Nero completely lost his childhood name upon being adopted by Claudius#which makes it that much more likely that it isn't chance that all of his kids have Roman names#he probably did give them Roman names when they were adopted into the Imperial Household#which makes Meg keeping her name all the more a mark of special treatment

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sestertius of the notorious Roman emperor Commodus, minted at Rome in 192 CE, the last year of his reign. On the obverse, the bust of Commodus; on the reverse, the personification of Africa greets Hercules. Africa holds a sheaf of wheat (representing the grain the province produced) and a sistrum (the rattle associated with the goddess Isis), while Hercules stands on a ship's prow and holds his club.

The seemingly innocuous imagery of this coin masks the megalomania that characterized Commodus' final years. He is here styled Lucius Aelius Aurelius Commodus, his birth name; his father Marcus Aurelius had renamed him M. Aurelius Antoninus Commodus upon making him Caesar, but Commodus ultimately spurned both this name and his father's heritage. His identification with Hercules, a constant of his reign, reached a fever pitch at this time: the emperor officially styled himself "Roman Hercules" (Hercules Romanus) and engaged in beast-hunts (venationes) and gladiatorial matches designed to evoke Hercules' Twelve Labors. (In one infamous incident, he threatened to cast the audience in the arena as the Stymphalian Birds and mow them down with arrows.) Taking a dizzying array of new cognomina (Amazonius, Invictus, Exsuperatorius, etc.), Commodus demanded that each month of the year be named after one of his titles, and he even floated the idea of renaming Rome Colonia Aelia Commoda after himself. By December 192 his advisors had had enough, and a conspiracy was put in train, into which his mistress Marcia was recruited. She poisoned him; when this did not kill him, his personal trainer, one Narcissus, strangled him in his bath. With him ended the dynasty begun by Nerva nearly a century before.

Photo credit: Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com

#classics#tagamemnon#Ancient Rome#Roman Empire#ancient history#Roman history#Commodus#art#art history#ancient art#Roman art#Ancient Roman art#Roman Imperial art#Hercules#classical mythology#coins#ancient coins#Roman coins#Ancient Roman coins#sestertius#metalwork#brass#brasswork#numismatics#ancient numismatics

151 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Roman Bust of Emperor Lucius Verus

Second half of the 2nd century AD

Marble over life-size portrait bust of emperor Lucius Verus, wearing a cuirass (breast-plate and back-plate) and a paludamentum (cloak), fastened by a fibula (brooch) on his right shoulder.

H. 99.5 x w. 67.5 cm.

Lucius Aurelius Verus (15 December 130 – January/February 169) was Roman emperor from 161 until his death in 169, alongside his adoptive brother Marcus Aurelius. He was a member of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty. Verus' succession together with Marcus Aurelius marked the first time that the Roman Empire was ruled by more than one emperor simultaneously, an increasingly common occurrence in the later history of the Empire.

Born on 15 December 130, he was the eldest son of Lucius Aelius Caesar, first adopted son and heir to Hadrian. Raised and educated in Rome, he held several political offices prior to taking the throne. After his biological father's death in 138, he was adopted by Antoninus Pius, who was himself adopted by Hadrian. Hadrian died later that year, and Antoninus Pius succeeded to the throne. Antoninus Pius would rule the empire until 161, when he died, and was succeeded by Marcus Aurelius, who later raised his adoptive brother Verus to co-emperor.

As emperor, the majority of his reign was occupied by his direction of the war with Parthia which ended in Roman victory and some territorial gains. After initial involvement in the Marcomannic Wars, he fell ill and died in 169. He was deified by the Roman Senate as the Divine Verus (Divus Verus).

#Emperor Lucius Verus#Roman Bust of Emperor Lucius Verus#Second half of the 2nd century AD#marble#marble bust#marble statue#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient rome#roman history#roman empire#roman emperor#roman art

48 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Claudia Livia Julia, known as Livilla, or "Little Livia", was a daughter of Drusus and Antonia Minor, being thus a granddaughter of empress Livia, of Mark Antony and of Octavia Minor. Livilla was married twice, both times to would be emperors: Gaius Caesar, emperor Augustus' grandson, and Drusus Caesar, emperor Tiberius' son. Though her husbands never became emperors, their positions as potential successors during their lives meant that Livilla herself had an important role within the royal family, making her the most probable successor to Livia as empress. Certainly the remarkably beautiful Livilla had enough ambition to match her status. Livilla began an affair with the also ambitious praetorian prefect Lucius Aelius Sejanus, who plotted to overthrow Tiberius. To help her lover, Livilla allegedly poisoned the emperor's son, her husband Drusus. After Drusus' death, Sejanus requested Tiberius for Livilla's hand, but his plans against the emperor were discovered and the marriage never took place. Livilla's death happened shortly after Sejanus' fall, either by murder or by suicide.

Vipsania Agrippina, known as Agrippina Maior, had an even more distinguished ancestry than Livilla, being a granddaughter of Augustus himself. She was married to Livilla's older brother Germanicus, the most popular general of his time and Tiberius' adopted son and heir. Agrippina was a constant companion of her husband, travelling with him throughout his career, which was extremely uncommon, but it was after his suspicious death that she took centre stage in Roman politics, openly claiming that her husband had been murdered to promote Tiberius' son Drusus as heir. As Augustus' granddaughter, Agrippina saw herself and her family as the rightful heirs to the imperial throne. Tiberius mistrusted Agrippina and Livilla's lover, Sejanus, saw her and her sons as the biggest threat to his power, so they worked to have her and her two oldest sons exiled and killed.

Livilla and Agrippina were close in age and rank and natural rivals inside the imperial family. Although neither managed to become empress, in the long term Agrippina triumphed over Livilla: her son Caligula went on to become emperor, ordering the death of Livilla's son Gemellus in the process, Agrippina's daughter, also named Agrippina, became empress, and her grandson Nero was the last emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Agrippina was long remembered as noble and brave for her fight against Tiberius and defense of her husband and sons, while Livilla's image was tainted by her affair with Sejanus.

#perioddramaedit#historyedit#ancient rome#julio claudian dynasty#nobody:#not a single soul:#me: who wants another gifset about the julio claudians lol#g*

329 notes

·

View notes

Photo

3 generations of antonii + the lovers they committed treason with

mark antony rose to power after the death of julius caesar and allied himself with queen cleopatra vii of egypt; the two soon became lovers, which scandalized rome. antony’s rival, octavian, used his affair with cleopatra as proof that he was a slave to egypt and a traitor to rome. octavian defeated antony and cleopatra in the civil war, and they both committed suicide in 30 BCE. octavian would soon become known as augustus, the first emperor of rome.

iullus antonius, the son of mark antony and fulvia, was involved in a scandal with augustus’s daughter julia and several other elite men in 2 BCE. ostensibly their crime was adultery, but both ancient writers and modern scholars have speculated that there was some degree of political conspiracy to the group’s activities. iullus was put to death and julia was sent into exile, where she died in 14 CE of unknown causes, perhaps starvation.

livilla, the daughter of drusus and antonia minor and therefore the granddaughter of mark antony, was married to emperor tiberius’s son drusus the younger, whom she allegedly poisoned with the help of her lover, the ambitious praetorian prefect lucius aelius sejanus. in 31 CE tiberius had sejanus arrested for plotting to overthrow him. sejanus was strangled and his body thrown down the gemonian steps, and shortly afterwards livilla either committed suicide or was starved to death by her mother.

#historyedit#classicsedit#tagamemnon#ancient rome#mark antony#cleopatra#iullus antonius#julia#livilla#sejanus#rome @ the gens antonia: could you not be dumb treasonous hoes FOR FIVE MINUTES?!#god i love this family

617 notes

·

View notes

Text

some pointless but fun facts about lucio’s birthdate (Jan. 13) because i fell down a rabbit hole and help i can’t get up

some people say its the beginning of the satanic new year. not a whole lot of sources on this but some people do say it. so, there’s that.

which could be because it was the day before the Old New Year in the Julian calendar. but thats me just trying to make a connection between these two similar facts

Also!! Emperor Hadrian’s appointed successor, Lucius Aelius Caesar, was born on this day! He died before he was ever able to ascend to the throne from an illness around the age 36, give or take a few years.

do these mean anything? not really, but I think they’re interesting ig 🤪

#yeah fuck it ill tag it#the arcana#count lucio#im very excited about hadrian because i love hadrian hes my fav roman emperor

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Antoninus Pius, in full Caesar Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Augustus Pius, original name Titus Aurelius Fulvius Boionius Arrius Antoninus, (born Sept. 19, 86, Lanuvium, Latium—died March 7, 161, Lorium, Etruria), Roman emperor from AD 138 to 161. Mild-mannered and capable, he was the fourth of the “five good emperors” who guided the empire through an 84-year period (96–180) of internal peace and prosperity. His family originated in Gaul, and his father and grandfathers had all been consuls. After serving as consul in 120, Antoninus was assigned by the emperor Hadrian (ruled 117–138) to assist with judicial administration in Italy. He governed the province of Asia (c. 134) and then became an adviser to the Emperor. In 138 Antoninus was adopted by Hadrian and designated as his successor. Hadrian specified that two men—the future emperors Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus—were to succeed Antoninus. Upon acceding to power, Antoninus persuaded a reluctant Senate to offer the customary divine honours to Hadrian. For this, and possibly other such dutiful acts, he was given the surname Pius by the Senate. When his wife, Faustina, died in late 140 or early 141 he founded in her memory the Puellae Faustinianae, a charitable institution for the daughters of the poor. References to Antoninus in 2nd-century literature are exceptionally scanty; it is certain that few striking events occurred during his 23-year reign. A rebellion in Roman Britain was suppressed, and in 142 a 36-mile (58-kilometre) garrisoned barrier—called the Antonine Wall—was built to extend the Roman frontier some 100 miles north of Hadrian’s Wall (q.v.). Antoninus’ armies contained revolts in Mauretania, Germany, Dacia, and Egypt. The feeling of well-being that pervaded the empire under Antoninus is reflected in the celebrated panegyric by the orator Aelius Aristides in 143–144. After Antoninus’ death, however, the empire suffered invasion by hostile tribes, followed by severe civil strife. #ancientrome #romanempire #rome #roma #spqr #romanhistory #antoninuspius #emperors #numismatics #venividivici https://www.instagram.com/p/ByM-qfWA8kc/?igshid=eiitv65jl0j3

#ancientrome#romanempire#rome#roma#spqr#romanhistory#antoninuspius#emperors#numismatics#venividivici

2 notes

·

View notes