#produced by claude chabrol

Photo

211. O Signo do Leão (Le signe du lion, 1962), dir. Éric Rohmer

#cinema#éric rohmer#jess hahn#french cinema#1960s movies#classic movies#b & w movies#drama#zodiac sign#composer#telegram#inheritance#fortune#bohemian#homelessness#poverty#chance#nouvelle vague#french new wave#produced by claude chabrol#60th anniversary#cult director#cinefilos

0 notes

Text

THE ZONE OF INTEREST (Jonathan Glazer, 2023)

Cuando vi esta película por primera vez en el Festival Internacional de Cine de Gijón, inmediatamente se me vinieron a la cabeza obras como 2001: A Space Odyssey o There Will Be Blood. ¿Qué motivos impulsaron a Jonathan Glazer a tomar decisiones formales tan arriesgadas? ¿Por qué ese arranque? ¿Por qué esa obertura? Quizá, de una forma paradójica y alegórica, se pretende enfatizar la idea de que las imágenes que otorgan entidad a la película intentan rebelarse contra sí mismas para no ser mostradas. Resulta entonces imposible ignorar la figura de Claude Lanzmann y su memorable digresión en torno a la ética, la moral y la exposición de la infamia.

Dado que la película se filma desde el punto de vista de lo inconcebible, adopta un carácter observacional, flemático y ascético que, en ocasiones, podría disociarnos de la atrocidad y acercarnos a un escenario costumbrista y rutinario. Ahora bien, si el medio es el mensaje —tal y como afirmaba Marshall McLuhan— o, si se prefiere, la forma crea el contenido —deducción archiconocida de Chabrol en referencia al cine de Hitchcock—, entonces lo verdaderamente revelante y relevante para entender esta película se localizaría en el formato utilizado, así como en su óptica y sonoridad. Elementos que aluden de forma constante al contraplano que jamás se muestra y que, por ello, trasciende aún con mayor contundencia y hondura. Al otro lado de esos muros de contención quizá podríamos descubrir al miembro de los Sonderkommandos Saul Ausländer de la película de László Nemes pero, en The Zone of Interest, la materialización fílmica de esa evocación se nos muestra en formato negativo, habitando un terreno aparentemente ilusorio cuya transmutación en realidad se consuma cuando la narración retorna a los quehaceres domésticos y mundanales que viabilizan la preservación del punto de vista heterodiegético.

Aquellos que hayan leído la novela en que se basa se habrán percatado de que Jonathan Glazer tan solo la utiliza como punto de partida, si bien es cierto que para con algunas de sus escenas funciona perfectamente como subtexto de acompañamiento. Martin Amis ficciona una trama y la sitúa en un momento histórico determinado. La película, sin embargo, se aleja de este enfoque, lo que permite que incida con mayor profundidad en su condición empírica y cáustica.

Los momentos en que la pantalla se satura por completo de colores elementales, incorporan fugaces instantes de reflexión ante unas imágenes que supeditan sus formas de arte y representación a la realidad misma que las fundamenta. Esta explicitación articula la parte emocional. La inverosímil y admirable composición musical de Mica Levi converge con el material filmado para convulsionar el relato y el ideario subyacente. Es aquí donde volvemos a la intersección de una disonancia inarmónica que se superpone a ciertos sonidos y situaciones sumidas en la más absoluta cotidianidad. Por otro lado, la ceremonia litúrgica que abre y cierra la película entre tinieblas, el blanco cegador despojado de su pureza o el rojo sangre como encarnación de lo abominable, serían ejemplos paradigmáticos de este aparataje sensitivo.

En su parte final, Rudolf Höss nos devuelve la mirada y desdibuja la línea temporal que se había mantenido hasta ese momento. Jonathan Glazer se transforma entonces en un pseudodocumentalista para mostrarnos imágenes recientes del Museo de Auschwitz y la película nos recuerda que ninguna situación pasada, presente ni futura debería permitirnos tomar distancia ante determinados sucesos que fueron, son y serán.

En el año 2019 Jonathan Glazer filmó un cortometraje basándose en la obra El sueño de la razón produce monstruos de Goya y, en él, anticipa buena parte de este planteamiento. Los personajes de esta pieza de cámara ocultan sus rostros y cuerpos bajo disfraces, de lo cual se puede inferir que cualquiera de nosotros podría ser uno de ellos. Llegados a este punto, quizá no resulte tan sencillo obviar la ignominia que nos rodea.

Se trata de una mera coincidencia, pero tras asistir a la proyección de la película estuve leyendo la novela Stella Maris de Cormac McCarthy. De su pluma y de la mente esquizofrénica del personaje de Alicia Western surgió de repente un pasaje que rápidamente identifiqué como una derivación de lo que había visto en pantalla. Es este:

"Coges una serie de imágenes fijas y las pasas en tándem a una determinada velocidad ¿y qué es eso que parece la vida misma? Nada más que una ilusión. ¡Anda! ¿Y qué es eso? Bah, qué importa si así haces que vuelvan los muertos. Lógicamente ellos no tienen gran cosa que decir. ¿Qué quieres? Llame antes de excavar. Habrá quien piense que el truco está en encontrar la pista de alguna realidad colateral. Por si no pillas la falacia implícita. La pertinente malicia. Puedes aportar vectores nuevos, aunque eso no es señal de que vayan a funcionar. ¿Te parece una buena idea? ¿Y si la gente quiere volver?

La gente no puede volver.

Así me gusta. La gracia está en que nunca vas a tener una pantalla en blanco. Y por supuesto lo que cuenta no es lo que se ve sino quién lo puso allí. Si en un momento dado miras y no hay nada en la pantalla ya lo pondrás tú misma, por qué no"

#the zone of interest#la zona de interes#jonathan glazer#christian friedel#sandra huller#ralph herforth#max beck#marie rosa tietjen#sascha maaz#stephanie petrowitz#lilli falk#freya kreutzkam#ralf zillmann#imogen kogge#nele ahrensmeier#johann karthaus#daniel holzberg#medusa knopf#luis noah witte#christopher manavi#zuzanna kobiela#julia polaczek#wolfgang lampl#film#cine

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog Entry 1

French New Wave (Godard, Truffaut, Varda, Rohmer, Chabrol, Resnais)

The focus of my first blog will be on the French New Wave which was notably developed in the late 1950s in Paris. The primary people and essential factors of this movement consist of directors Jean Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer, Agnes Varda, and Alain Resnais. This movement was the rise of French cinema in a way that was never seen before. Many innovations such as cut scenes and hand held cameras were used to make an overall more experimental approach to creating a different type of cinema. Interestingly enough, given a brief explanation of what the French New Wave is and the time period it peaked, it is often claimed to be the “birth of modern cinema”. This film type was developed from the influence of Italian Neorealism or better known as the Golden Age. This classification of motion pictures was based on the poor and working class and like the French New Wave, used amateaur actors that either weren’t professional or were not well known; mainly due to the reality that these directors didn’t have the finances to support proper filming standards, but the more liable answer to all this is about experimentation. Also related to how they were produced, the French New Wave typically consisted of films that held more personal values and were shot in a very different manner which could be compared to more of a documentary style in today's day in age. The main concept was that the director had a more free flowing control of the work which is where the “auteur theory” came alive which simply means that the director is the main driving force of the cinematic work and has the ability to use his creativity to implement it into the film. The complexity of these pieces varied depending on the director but overall created a more difficult concept of morals for viewers to pick up and understand. This was done purposely as it was a repetitive theme throughout the movement. There was a constant drive from each of the directors to try and challenge the viewers in some way whether it’s coming from the concept or the way the film was created. Personally, the characteristic that interested me the most and essentially the most important aspect was the idea of rejecting large studio companies in order to illuminate the ideas and constructive ways of the director to focus on their ideas specifically. This was interesting because studio productions provide the filmmakers and participants with ample resources to create the best possible film with a given budget but with this case, it was different as movies made during the French New Wave were all alike in the aspect of ways of filming and of storytelling. Because of its early success and production, the influence on various global film movements has become prominent which all began with this creative group of French directors who felt they could change the way entertainment was viewed as a whole. Although there are plenty of influencing factors from this movement in today's film industry, this wave was said to have ended in the early 1960s around the year 1964. An intriguing movement with a great deal of popularity and praise, the French New Wave has made a remarkable impact in the film industry.

Sources:

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

For my blogs I will be writing about The French New Wave and the impacts it has had on the global film industry. For the first blog I will be writing about how The French New Wave came to be as well as how it has inspired many directors and actors. I have been interested in this topic since I leaned about it last year in my intro to film class. The French New Wave came about shortly after the end of the second world war in the late 1940s. French people were longing for cinema they could call their own. The Fenech wanted to turn away from American ideas such as censorship in films and make their own mark on cinema history. With The French New Wave audiences could experience a new genre of film that was exciting and fresh in a period when audiences craved something new after a turbulent few years coming off the tail end of the war. Some prominent directors that helped establish The French New Wave are Jean-Luc Godard, Agnus Varda, (also known as the Queen of The French New Wave) and Jacques Rivette. These directors were some of the first in their field to take on this new idea of cinema. They helped incorporate ideas free from rejection and the strong narrative that was present in the classic Hollywood films of the 40s and 50s. Some classic French New Wave films are My life to live, La Pointe Coute, and Shoot the Peano Player. These films helped establish what is known as the French New Wave by allowing audiences to experience a new genus of film that was on the rise of popularity as well as inspire a new generation of film makers to come. The French New Wave has been inspirational for braking some of the most important classic studio system norms such as big budget films and the rules of storytelling in cinema as we knew it. With The French New Wave Directors could try new things such as new filming location and how film was shot. Experimenting with new camera angels as well as new tools that Hollywood had yet to discover. The French New Wave inspired directors such as the Danish director Dogma 95, the filmmaking of cinema novo and new Hollywood. The French New Wave paved the way for young up and coming producers and actors such as Louis Mallie, Claude Chabrol, and Francois Truffaut. Today we can see the French new wave in many forms such as movies of today, books and even pieces of art. The French new wave has been an inspiration for decades inspiring many directors, actors, and producers. The French New Wave will continue to inspire many more who wish to fallow in the footsteps of the people who dared to be different and create a genre of film that questioned everything that was set in stone as the road map we call cinema. As people discover this unique style of film it will no doubt live on for many generations to come long after we are gone.

https://studentbridgew-my.sharepoint.com/:p:/r/personal/oflood_student_bridgew_edu/Documents/Presentation.pptx?d=w36ca9e8bdb074b56acf5ab8129bc86b5&csf=1&web=1&e=azX733

1 note

·

View note

Text

Tarakben Ammar Net Worth, Wife, Daughter, Age, Wiki, Ethnicity, Net Worth & More

Tarakben Ammar Net Worth:- Tarakben Ammar is a well-known Tunisian-French film producer and distributor. He is also the owner of French production and distribution company Quinta Communications. He is also known for his interest in artistic films, especially when they relate to Mediterranean culture or require North African locations.

He was also producing the Franco Zeffirelli film adaptation of La Traviata and Claude Chabrol’s Death Rite. He became renowned in France, at the beginning of 2004. He is also populer as the advisor of international investor Prince Al Waleed Bin Talal Bin Abdul Aziz.

VisitThis Site = https://latestinbollywood.com/tarakben-ammar-net-worth-wife/

0 notes

Text

June 24 ZODIAC

They are very respectable, steady, erotic, blissful, they appreciate interruptions and games, music, life in extravagance and solaces. It should be added that they are smart individuals, very shrewd and enterprising. Specifically, they target different mystery plans and activities. They head out in a different direction with a great deal of persistence, despite the fact that they don't necessarily finish things eventually. They appreciate functions and official appearances. They are rich and blessed with a specific ability for acting. They are intrigued by the excellence of the scenes, blossoms and plants. They would rather not practice a lot throughout everyday life. In spite of the fact that they can be exceptionally dynamic, they need a lighthearted life. Their defects are narrow-mindedness and envy, and they don't make a special effort to offer courtesies to others. Their nuances and shrewd as a rule clear their path through life. They need to live in flourishing and solace no matter what, with moral splits the difference or aspirations.

June 24 ZODIAC

On the off chance that your birthday is June 24, your zodiac sign is Disease

June 24 - character and character

character: mindful, energetic, bright, horrendous, insane, unreasonable calling: stylist, cosmetologist, secretary tones: pink, beige, blue stone: topaz creature: gazelle plant: Snapdragon fortunate numbers: 2,7,30,46,51,53 very fortunate number: 1

Occasions and observances - June 24

Argentina: We Tripantu, Ano Nuevo Mapuche, Holiday de San Juan (in the territory of San Juan), Auto Dashing Day, Soccer Day celebrating the introduction of Lionel Messi and Pilot Day recognizing the introduction of Argentine driver Juan Manuel Fangio

Peru: Inti Raymi (Celebration of the Sun particularly Cusco), Holiday de San Juan (in every one of the towns of the Peruvian Wilderness) and Day of the Laborer

Canada: Public Occasion of the Territory of Quebec.

Mexico (Guadalupe, Zacatecas): La Morisma de Guadalupe out of appreciation for Holy person John the Baptist.

Colombia, Tamale Day in the city of Ibague

Mexico (Chiapas): San Juan Chamula.

Chile: We Tripantu, Mapuche New Year.

Venezuela: Day of San Juan Bautista, Evening of San Juan Bautista, Day of the Public Multitude of Venezuela.

June 24 VIP birthday celebrations. Who was conceived that very day as you?

1901: Marcel Donkey, French traditional saxophonist, soloist and teacher (f. 2001). 1901: Harry Partch, American arranger (d. 1974). 1901: Ricardo Saprissa, Salvadoran-Costa Rican soccer player and financial specialist (d. 1990). 1904: დ?ngel Garma, Spanish-Argentine therapist (f. 1993). 1908: Hugo Distler, German arranger (d. 1942). 1910: Guillermo Sautier Casaseca, Spanish author (d. 1980). 1911: Juan Manuel Fangio, Argentine Recipe 1 driver (f. 1995). 1911: Ernesto Sabato, Argentine writer and writer (d. 2011). 1912: Juan Reynoso Portillo, Mexican violin player (d. 2007). 1913: Juan Criado, Peruvian footballer, vocalist lyricist and writer (d. 1978). 1913: Gustaaf Deloor, Belgian cyclist (d. 2002). 1913: Jan Kubish, Czech warrior (d. 1942). 1914: Humberto Briseno Sierra, Mexican law specialist, teacher and scholastic (f. 2003). 1914: Juan Grela, Argentine painter and printmaker (d. 1992). 1914: Luis Sდ¡nchez Agesta, Spanish law specialist, teacher and scholastic (f. 1997). 1915: Sir Fred Hoyle, English astrophysicist and essayist (d. 2001). 1923: Yves Bonnefoy, French writer, interpreter and workmanship pundit (d. 2016). 1927: Martin Lewis Perl, American physicist, Nobel Prize in Material science in 1995. 1927: Osvaldo Zubeldia, Argentine soccer player (d. 1982). 1928: Argentino Ledesma, Argentine artist (d. 2004). 1930: Claude Chabrol, French producer (d. 2010). 1932: Antonete (Antonio Chenel), Spanish matador (d. 2011). 1932: Queta Claver, Spanish entertainer (f. 2003). 1933: Sam Jones, American ball player. 1935: Juan Carlos Rousselot, Argentine columnist and legislator (d. 2010). 1938: Lawrence Block, American essayist. 1940: Vittorio Storaro, Italian cinematographer. 1941: Julia Kristeva, French scholar, psychoanalyst and author. 1942: Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle, Chilean president somewhere in the range of 1994 and 2000. 1942: Colin Forests, Australian primatologist. 1944: Petra Martდnez, Spanish entertainer. 1944: Jeff Beck, English artist, of the band The Yardbirds. 1944: Arturo Goetz, Argentine entertainer (d. 2014). 1945: Mario Alarcდ³n, Argentine entertainer. 1946: Ellison Onizuka, American space explorer (d. 1986). 1948: Armando Calderდ³n Sol, Salvadoran president somewhere in the range of 1994 and 1999. 1948: Steve Patterson, American ball player (d. 2004). 1949: John Illsley, English bassist. 1953: Laura Cepeda, Spanish entertainer. 1957: Luis Salinas, Argentine guitarist 1961: Terse Smith, English performer. 1962: Lancaster Gordon, American ball player. 1964: Fდ©lix de Bedout, Colombian columnist. 1967: Richard Z. Kruspe, German guitarist, of the band Rammstein. 1968: Jaime Enrique Aymara, Ecuadorian artist. 1968: Anna Ciocchetti, Mexican entertainer. 1971: Tony Hernდ¡ndez, Mexican artist lyricist and guitarist. 1972: Robbie McEwen, Australian cyclist. 1977: Josდ© Antonio Crespo, Spanish badminton player. 1978: Luis Garcდa, Spanish footballer. 1978: Shunsuke Nakamura, Japanese footballer. 1978: Juan Romდ¡n Riquelme, Argentine footballer. 1978: Emppu Vuorinen, Finnish guitarist. 1980: Cicinho (Cდcero Joao de Cezare), Brazilian soccer player. 1981: Johnny 3 Tears, artist of Rap Rock. 1982: Kevin Nolan, English footballer. 1982: Christian Montero, Costa Rican soccer player. 1982: Serginho Greene, Dutch footballer. 1983: Sofდa Mulდ¡novich Aljovდn, Peruvian surfer. 1983: Ariel Kenig, French essayist and writer. 1984: Osvaldo Noდ© Miranda, Argentine footballer. 1984: JJ Redick, American ball player. 1985: Diego Alves Carreira, Brazilian soccer player. 1986: Solange Knowles, American entertainer, model and artist. 1986: Francisco Munoz, Chilean pilot and city hall leader of La Reina. 1987: Lionel Messi, Argentine footballer. 1987: LiSA, Japanese artist. 1988: Micah Richards, English footballer. 1988: Facundo Ardusso, Argentine pilot. 1991: Mutaz Essa Barshim, Qatari competitor. 1992: Raven Goodwin, American entertainer. 1992: David Alaba, Austrian footballer. 1993: Piero Barone, Italian artist.

0 notes

Audio

(Literary License Podcast)

Book: The Talented Mr Ripley

By Patricia Highsmith

Film: The Talented Mr Ripley (1999)

The Talented Mr. Ripley is a 1955 psychological thriller novel by Patricia Highsmith. This novel introduced the character of Tom Ripley, who returns in four subsequent novels. It has been adapted numerous times for film, including the 1999 film of the same name.

The Talented Mr. Ripley is a 1999 American psychological thriller film written and directed by Anthony Minghella, and based on Patricia Highsmith's 1955 novel of the same name. It stars Matt Damon as Tom Ripley, with Jude Law, Gwyneth Paltrow, Cate Blanchett and Philip Seymour Hoffman in supporting roles. The novel was previously filmed twice. In 1957, a one-hour version was produced for the TV anthology series Studio One, directed by Franklin J. Schaffner, though no recording survives. In 1960, a full-length film version was released, titled Purple Noon (French: Plein soleil) and directed by René Clément, starring Alain Delon in his first major role. Claude Chabrol's 1968 film Les biches ('The Does') uses many elements of Highsmith's novel but switches the gender of the main characters. The film was a critical and commercial success. It received five Academy Award nominations, including Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Supporting Actor for Law.

Opening Credits; Introduction (2.31); Background History (10.18); Plot Synopsis (10.53); Book Thoughts(15.40); Let's Rate (34.54); Introducing a Film (36.59); Film Trailer (37.48); Lights, Camera, Action (39.56); How Many Stars (1:14.52); End Credits (1:16.27); Closing Credits (1:17.27)

Opening Credits– Epidemic Sound – copyright 2021. All rights reserved

Closing Credits: Tu vuò fà l'americano by Renato Carsone. Copyright 1956 Pathe records.

Original Music copyrighted 2020 Dan Hughes Music and the Literary License Podcast.

All rights reserved.

All songs available through Amazon Music.

#SoundCloud#music#Literary License Podcast#Entertainment#The Talented Mr Ripley#Patrica Highsmith#Matt damon

0 notes

Photo

(Michael Wechsler and I attended Sundance, or really *crashed* Sundance, in 1995, with the goal of promoting our not-yet-finished feature at the place where everyone in the independent film world was sure to be. Filmmakers screening at Sundance put their posters up all over the place, largely on the walls of Main Street in Park City. These posters advertise screening times for that week in Sundance. Our poster had the title of the film, our mock "Godfather puppet hand" logo and said "Coming Soon," with our phone number, which went to a voicemail. We got a lot of phone calls, including one from legendary French film magazine Cahiers du Cinema, which included François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Claude Chabrol, Jacques Rivette, and Eric Rohmer amongst its founders. The reporter spoke to us about what we were doing and included us in her wrap-up about Sundance, albeit mainly in the footnotes of the piece.

Like the blurb in the New York Times when it was considered groundbreaking that we used email to promote our film in 1999, it was considered unique by the press in 1995 that we'd put a poster up for a film that wasn't even finished yet, at Sundance.

1995 was a seminal year at the Dance. My USC classmate Bryan Singer, who had won the festival a few years before with his debut indie Public Access, was catapulted to director stardom with the first screening of The Usual Suspects, which we were in attendance for. Although Public Access (written by Christopher McQuarrie, who also penned Suspects) had taken the big prize earlier in the decade, that meant less back then than it would today. The film wasn't released, and even then mainly into video stores, until sometime after The Usual Suspects was a hit years later, and reviews were somewhat tepid. But The Usual Suspects was destined for quite the opposite. The night the film premiered, there was audience electricity in the Egyptian Theater as Kevin Spacey became Keyser Soze. By the film's second screening the next afternoon, Robert Redford himself made one of his increasingly rare appearances, sitting in the back. Redford had clearly heard the buzz and needed to see this one for himself. Necks craned in the theater to catch a glimpse of Redford. There was extra laughter at that screening when Peter Greene's character of "Redfoot" was introduced. It sounded like his name was "Redford," and everyone assumed it was a reference to the star in the back of the theater. I'm still pretty sure it was a reference to Redford.

The next day, Bryan told us that he had been invited to visit Redford at his house that afternoon. It was like the hand of the King had anointed him. We were a little jealous, of course, although Bryan was pretty cool in the way he presented things like that to those who knew him when, in that he was never a braggart. It was more, "Jesus, I just got invited to Redford's place! Can you believe it?!" We were all like Freshman who had watched one of our own get invited to the prom by the coolest kids in the class, and we were happy for him, envious, and hoping we would also get a similar invite someday. Later in the decade, Wechsler and I would, in fact, get a call from Redford's office, when we got a good review in the L.A. Times, but it never led to anything much other than a good story.

1995 was also the first year of the Slamdance Film Festival, and where I met Slamdance co-founder Dan Mirvish, who I would produce the film 18 1/2 with, some 25 years later. The Slamdance directors were also putting their posters up for their alternative festival screenings, right next to the Sundance posters, and our posters. Redford himself also reached his hand to Slamdance and gave it a swat if sorts, with a quote to the press, "There is a festival that has attached itself to us in a parasitical way..."

The times were changing: if you didn't let filmmakers into Sundance, they weren't just going away, and they would show up at the Park City party anyway.)

Translation of Cahiers Du Cinema Blurb:

At Sundance, the action takes place outside the screening rooms. On the walls of the Egyptian Cinema, where we rested our soles during the lines of action in the cold, we could see a poster announcing the upcoming release of Slaves of Hollywood (an allusion to the title of Tama Janowitz's bestseller transformed into a rather uncut film by Merchant-Ivory), and giving a telephone number. According to information, this is the first film by two young directors, in search of a distributor, which describes the tribulations of six young people struggling to "succeed" in Hollywood.

0 notes

Text

Les Cousins (1959)

Les Cousins by #ClaudeChabrol, "the perfectly-wrought performances make a film that is, seemingly, an aimless character study feel as carefully mapped out as a great mystery narrative"

CLAUDE CHABROL

Bil’s rating (out of 5): BBBB

France, 1959. Ajym Films, Société Française du Cinéma pour la Jeunesse. Scenario by Claude Chabrol, dialogue by Paul Gegauff. Cinematography by Henri Decae. Produced by Claude Chabrol. Music by Paul Misraki. Production Design by Bernard Evein, Jacques Saulnier. Film Editing by Jacques Gaillard.

Claude Chabrol’s sophomore directorial effort has him…

View On WordPress

#Abdou Filali#Ajym Films#André Chanal#André Jocelyn#Anne Zamire#Berlin 1959#Bernard Evein#Catherine Candida#Chantal Bouchon#Christian Pezey#Clara Gansard#Claude Cerval#Claude Chabrol#Colette Teissèdre#Corrado Guarducci#Criterion Collection#Emmanuel Pierson#Françoise Vatel#France#Gaby Blondé#Gérard Blain#Genevieve Cluny#Gilbert Edard#Guy Decomble#Henri Decae#Jacques Deschamps#Jacques Gaillard#Jacques Kemp#Jacques Ralf#Jacques Saulnier

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Siren Song.

Undine writer-director Christian Petzold talks to Reyzando Nawara about modern-day mermaids, Tinder culture and finding the magic in life.

“Love stories always change. A kiss in Berlin 1933, for example, is not gonna be the same kiss in Berlin today, right?” —Christian Petzold

“If you leave me, then I’ll have to kill you.” Undine’s threat to her soon-to-be ex-boyfriend Johannes, after he has told her that he has met someone else, seems at first like an over-the-top reaction to the breakup. But it is a curse that Undine must fulfill, for she will become human only when she falls in love with a man who is doomed to die if he is unfaithful to her.

From Splash to Ponyo to The Lure to Song of the Sea, mythical water spirits, usually female, sometimes horse, have powered many film plots. The sixteenth-century European myth of Undine, in particular, lies behind many screen adaptations of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid, though the Danish writer was not the first to popularize the fairytale in his century. Decades earlier, around 1811, Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué of Germany had produced his romantic novella, Undine.

And it is to Germany—specifically modern-day Berlin—that writer-director (and fellow German) Christian Petzold transports Undine in his contemporary magical-realist take on the myth. There, she does not take the form of a mermaid or siren, but a beautiful young woman (played by Paula Beer), who works as a historian at a museum, where she guides tours of Berlin’s architecture and its reconstruction. The breathtaking cinematography, by regular Petzold collaborator Hans Fromm, crystallizes both the romance and the beauty of Berlin, while Petzold’s leads root every scene in reality, even as aquariums explode and giant catfish drift past.

Paula Beer and Franz Rogowski fire up the streets of Berlin in ‘Undine’.

Water may be the dominant element in Undine, but Beer and her co-star Franz Rogowski bring fire to their scenes together. Where Beer brings charisma and intensity to the titular role, Rogowski, as Undine’s new love interest, an industrial diver named Christoph, offers charm and sweetness.

In the frenzy of Parasite’s world domination, it is easy to forget that Petzold’s previous feature, Transit, appeared in two of our 2019 Year in Review lists—the 50 highest-rated films and the highest-rated international films—and was one of the top romance films of the 2010s. His riveting Phoenix is still his highest-rated film on the platform—one of many to center a complex female character in search of love at a time of personal and/or political crisis. In Undine, Petzold does it again, a welcome departure from other adaptations, including the Colin Farrell-starring Irish romantic drama Ondine (2009), that have mostly told the myth from the perspective of its male characters. Petzold also revises the fairytale, by giving Undine a chance to try to emancipate herself from her curse.

We recently had the pleasure of speaking with Petzold about his fascination with water, the magic of Berlin history, modern dating and of course, his ongoing collaboration with Beer and Rogowski.

Spoiler warning: this conversation contains plot details regarding the ending of Petzold’s film ‘Transit’ (2018).

Your movie is inspired by the myth of Undine, but you reinvent it by giving it some modern twists. How did the main narrative for the film come about?

Christian Petzold: I think the idea of the story first came to me around twenty years ago when I had a project in Germany. It was together with Claire Denis and also Kathryn Bigelow, and everybody had to make a ten-minute short film for a project based on the museum near the Rhine River. I had written a little dialogue—oh, by the way, Steve McQueen was also part of the project—and it was the scene that we can see in the movie in the first few minutes where Undine’s boyfriend, Johannes, said that he doesn’t love her anymore and that he wants to leave her and she said to him, “If you leave me, then I’ll have to kill you.” Then she goes back to work, and later when she comes back to try to find him again, he isn’t there—so she knows that she has to kill him now.

Then when I made Transit with Paula Beer and Franz Rogowski, I told them after a very lucky and happy time of shooting, that I had written a short story and wanted to make a 90-minute feature movie out of it together with them. I wanted to keep working and making movies with them because we’ve had an amazing experience together in Transit. This was basically the start of how the movie and my collaboration with these two actors came about.

Paula and Franz are actors who didn’t come from the basic German acting school; their backgrounds are dance and theater. But they both have so much curiosity about cinema—when I met Paula for the first time, for example, she told me that she had bought 50 movies by Alfred Hitchcock and wanted to see all of them, and to me, this is the best kind of school to learn about cinema.

So to some extent, Undine is a spiritual sequel to Transit?

Yes, you’re right. It has so many things to do with Transit. Marie, Paula’s character in Transit, finds her own death in the sea—she’s drowned. And Franz’s character, he’s waiting at the land, hoping that she may come back from the land of the dead. So I said to them, “Okay, the next movie is gonna be about a woman coming out of the sea and going to the land to search for love and also about this young man who is a diver, who is going underwater, to find love as well.” So to some degree, it’s a sequel, you’re right.

Beer and Ragowski in ‘Transit’ (2018).

You mentioned earlier that you had a great experience working with Paula and Franz in Transit. Can you tell us what it was about these two actors that you thought would capture the story you wanted to tell in Undine?

Paula is a very young actor—she was 23 when we started Transit, and she was around 24 when we made Undine—but when you’re filming her, she has this ability to make her characters much more mature beyond her real age. In one second, she’s 45 years old, with a whole experience of someone who’s had a hard life and has gone through so many bad things, then one second later, she’s thirteen and innocent. And to have that kind of ability—to go from one point to another—is just really fascinating to me. I’ve never seen other actors do this before in my life.

Franz was a dancer, and if I remember correctly, I think he was also in a clown school for a circus, so he can do everything with his body. It’s unbelievable what he can do. He has this amazing physicality that I admire and haven’t seen before in other German actors. When they’re together sharing a scene, they dance with each other. And this is the thing that I like so much about them and the thing I need in Undine, because I need actors who can float from one scene to another as if they’re dancing underwater.

In literature and pop culture, the myth of Undine has been mostly told from the male perspective. You reframe the narrative, to give Undine the opportunity to maybe emancipate herself from both the male figure in her life and the curse. Tell me more about that choice.

Two or three years ago, I had a retrospective in New York, and I had the chance to see some of my previous movies again—[laughing] I’ve actually never done it before, revisiting my own movies. And at that time, I realized that I’ve always tried to rewrite the stories centering on women, which were made by men in the ’40s, ’50s, ’60s and ’70s, from another perspective: the perspective of the women.

When I was in Venice for the first time, Claude Chabrol [was] in the same hotel as me, and he had a Q&A. I wanted to say hi and tell him how great he was but I couldn’t do it because I was very young and too shy for those things. I heard what he said when asked why in his movies, the women are always the main characters. His answer was, “Men are living, women are surviving. And cinema is about surviving.” It was such a fantastic answer.

All the movies I [have] made, including Undine, are about surviving. Undine wanted to survive her curse—she tries to, every time, since centuries ago. In so many iterations of the myth, Undine always has to go back into the lake and to the life the curse has set for her. I really wanted to zoom in on that, to liberate the character of Undine from the myth and the curse.

In the movie, Undine works as an historian at a museum, and in her tours, she talks about Berlin’s architecture and its reconstruction throughout the years. How is this related to the romantic aspect of the movie?

Everybody says you can take a love story and put it in the sixteenth century or the nineteenth century, and it’s always gonna be the same kind of love story. But I think that’s not entirely right. Love stories always change. A kiss in Berlin 1933, for example, is not gonna be the same kiss in Berlin today, right? Therefore I want to take the historical aspect of Berlin architecture and its reconstruction to tell the story of two young people in Berlin nowadays, to see the evolution of both this love story and the myth of Undine itself.

What’s the significance of all the buildings Undine mentions in the movie?

The buildings serve a very important role in the movie because Berlin is between two rivers on an island, and the city is built on dried-out swamps, so the element that Undine is coming from, which is the water, is destroyed in Berlin. It doesn’t exist anymore. And therefore Undine doesn’t have any habitats, so she has no choice but to adapt and to live on the land.

In some way, I always think that the modernization in Berlin erases history, and when there’s no history, there’s no magic, which means magical creatures like Undine won’t exist. That was the main idea of the architectural elements in the movie.

Is that also the reason why there are two locations in the movie: Berlin, and the small town where Franz’s character, Christoph, works and lives, which is still full of swamps? To show that in this small town, magic still exists?

That’s a good question. The romance and the myth of Undine is a part of German and European history. It’s a unique enchantment. But in Berlin, where modernization and civilization keep growing and changing, there’s no enchantment anymore. So I want to show how in this small town where everything is still kept as closely natural as possible, the enchantment and the charm of Germany are still there.

There’s a beautiful and romantic poem by Joseph Eichendorff that says, “You must find the right world, so everything can sync again.” To me, that line encourages us to find the magic of the world back. We live in this world surrounded by retro buildings and retro behavior and retro music, but it’s all actually just an illusion of magic. The real magic, that’s something that we have to find—either by movies or camera positions or poems or even by preserving the naturality of a city. And the Undine myth actually has a lot to do with this.

Another thing that fascinates me about the movie is how the dynamic between Undine and Johannes, in some way, reflects the state of modern dating. Is this something that you also wanted to capture when you wrote the script?

[Laughing] Funny story, when Paula read the script for the first time, she told me that she liked it so much because the story reminded her of Tinder and modern dating. And on some level, it’s true; part of Undine is about modern dating. I always think that in the era of dating apps, everything gets much simpler—you meet someone, you have sex (or perhaps not), and if you feel like this someone is not handsome or beautiful enough for you, you can keep scrolling until you find someone new. So, dating right now is like going to the supermarket.

Johannes leaving Undine to be with another woman, who for him is better-looking than Undine, reflects the culture of Tinder. And the line I mentioned earlier, “If you leave me, then I’ll have to kill you,” is the opposite of that kind of dating life. And Paula, who hates Tinder, loves that line a lot. Some of the actors are on Tinder, I’m sure, and that’s understandable. Actors are sometimes very lonely because for six to eight weeks, they are deep inside of a character, and when they’re on break, they’re in some sort of “black hole of loneliness”.

Writer-director Christian Petzold.

Undine being a water nymph, of course, makes the water element very important in this movie. But water has actually been heavily featured in some of your previous features as well, like in Yella, Barbara and Transit. Can you tell us why you find water fascinating?

I’ve seen a documentary by Agnès Varda, and in [it] she said, “The place where one element is touching one another is the place where cinema builds its stories.” That’s why she loved the beach, because on the beach, there’s water and there’s the earth and there’s also wind, and they’re touching each other. So to her, the beach is the perfect place where you can tell a story.

For me, however, the reason I like featuring water or the other elements in most of my movies is because it has something to do with seeing my characters coming from one element then going to the other elements; to see them act and react in a new and sometimes uncomfortable place. Also, when you see pictures or paintings, so many of them are about people looking deep into the sea. I always feel like that kind of painting is actually about a desire. And most of my movies, at [their] core, are about desire. That’s why water is so important to me. Deep under the water, there’s the place of desire.

What’s the first movie that made you want to become a filmmaker?

The first movie I loved very much as a kid was The Jungle Book, but the first movie that made me want to become a filmmaker was by Alfred Hitchcock, The 39 Steps. I was fourteen or fifteen years old when I saw the movie for the first time, and I loved it from the first moment. The movie is about a man and a woman who are bound by handcuffs, and they don’t like each other, but because they’re on the run, they have to communicate and come to an understanding. And the love story starts because of that communication, not because of looks, and I love the movie so much for that reason.

If you could program a double feature with Undine, what movie would you pick?

Good question. I would say The Night of the Hunter. Also maybe Creature from the Black Lagoon or 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea or The Son’s Room by Nanni Moretti. These are the movies that I would recommend for a double feature with Undine.

Related content

More ‘Little Mermaid’ adaptations: a list by Katherine

Paula Beer strolling around towns cinematic universe

Diogo’s mega-list of Mermaids in Film

Horror’s History with Scary Mermaids: a Bloody Disgusting list

Follow Reyzando on Letterboxd

‘Undine’ is in theaters and available on VOD in the US now.

#christian petzold#paula beer#transit film#undine#undine myth#ondine#water nymph#mermaids#mermaid film#german film#german director#german screenwriter#german cinema#cinema germany#romance#romance films#Reyzando Nawara#franz rogowski#letterboxd#filmmaker#letterboxd interview

24 notes

·

View notes

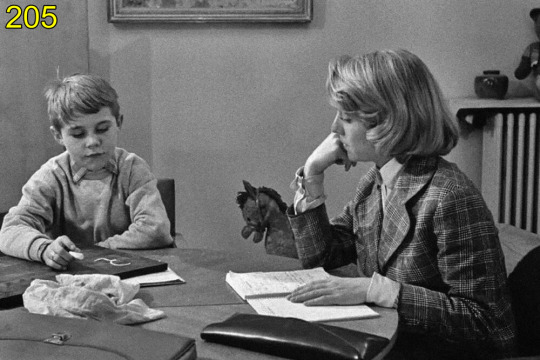

Photo

205. Véronique e seu Aluno Preguiçoso (Véronique et son cancre, 1958), dir. Éric Rohmer

#cinema#short movie#éric rohmer#nicole berger#alain delrieu#french cinema#classic movies#b & w movies#comedy#tutor#naughty child#nouvelle vague#french new wave#produced by claude chabrol#1950s movies#cult director#cinefilos

0 notes

Photo

Happy 89th, Alain Cavalier.

The American (1958), produced by Claude Chabrol and shot by Pierre Lhomme.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

English translation:

Cannes Film Festival: Jodie Foster will receive the Palme d'Or of honor

On July 6, the American director, actress and producer will kick off the 74th edition on the Croisette.

By Le Figaro

Posted at 11:29 a.m.

In 1976, when she was only 13 years old, Jodie Foster presented Taxi Driver in Cannes, and walked away with a Palme d'Or.

In 1976, when she was only 13 years old, Jodie Foster presented Taxi Driver in Cannes, and walked away with a Palme d'Or. Munawar Hosain / Startraks / ABACAPRESS.COM

Sponsored by fetchrewards.com

Fetch Rewards

GO!

Jodie Foster will receive the Palme d'Or of Honor at the Cannes Film Festival, and will be the guest of honor at the opening ceremony on July 6. The American director, actress and producer will kick off the 74th edition, which will end on Saturday, July 17 with the honors of the President of the Jury, Spike Lee. "Jodie Foster will receive the Palme d'Or of honor of the Festival which salutes a brilliant artistic career, a rare personality and a discreet but affirmed commitment for the great subjects of our time", writes the festival in a press release.

The Culture and Leisure newsletter

Newsletter

From Monday to Friday

Receive cultural news every day: cinema, music, literature, exhibitions, theater ...

E-mail adress

SUBSCRIBE

READ ALSO: Jodie Foster: "I like to talk about politics, but I hate political cinema"

ADVERTISING

Jodie Foster succeeds Jeanne Moreau, Bernardo Bertolucci, Jane Fonda, Jean-Paul Belmondo, Manoel de Oliveira, Jean-Pierre Léaud, Agnès Varda and Alain Delon, recipients of the Palme d'honneur before her. “Cannes is a festival to which I owe so much, it has totally changed my life,” she declares. My first visit to the Croisette was decisive. To present one of my films here has always been my dream (...). Cannes is an arthouse film festival that honors artists. I am very sensitive to it. ” For Jodie Foster, everything - or almost - had indeed started on the Croisette. In 1976, when she was only 13, she climbed the stairs to present Taxi Driver by Martin Scorsese. She left with a Palme d'Or.

Forty-five years later, Jodie Foster will once again receive a Palme honoring her entire career. Between these two dates, she collected about fifty roles, four productions and two Oscars - for The Accused in 1989 and The Silence of the Lambs in 1992. The actress wants to vary the genres: she goes from drama (Sommersby) to comedy (Maverick) without difficulty. Very attached to France - she speaks fluent French and her sister lives in Toulouse - Jodie Foster has also toured with Claude Chabrol (with whom she has worked three times) or Jean-Pierre Jeunet (A long engagement Sunday). In 2011, she presided over the 36th Cesar ceremony.

READ ALSO: Cannes Film Festival: many films at the turn

"I am flattered that Cannes has thought of me and I am very honored to be able to pass on a few words of wisdom or tell a few adventures to a new generation of filmmakers", Jodie Foster rejoices. An enthusiasm shared by Pierre Lescure, president of the festival. “Jodie Foster is giving us a wonderful gift by coming to celebrate the return of the Festival on the Croisette. Today, its aura is unparalleled: it embodies modernity, the radiant intelligence of independence and the demand for freedom, ”he believes.

#festival de cannes#Jodie Foster#cinema#lifetime achievements#gratitude#body of work#diversity#lesbian actors#activist#appreciation#director#women writers#risk taker#feminist

1 note

·

View note

Link

We lost one of the Great Film Makers yesterday. Her soul will live on In Cinema! Rest In Peace, Agnes! - Phroyd

Agnès Varda, a groundbreaking French filmmaker who was closely associated with the New Wave — although her reimagining of filmmaking conventions actually predated the work of Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut and others identified with that movement — died on Friday morning at her home in Paris. She was 90.

Her death, from breast cancer, was confirmed by a spokeswoman for her production company, Ciné-Tamaris.

In recent years, Ms. Varda had focused her directorial skills on nonfiction work that used her life and career as a foundation for philosophical ruminations and visual playfulness. “The Gleaners and I,” a 2000 documentary in which she used the themes of collecting, harvesting and recycling to reflect on her own work, is considered by some to be her masterpiece.

But it was not her last film to receive widespread acclaim. In 2017, at the age of 89, Ms. Varda partnered with the French photographer and muralist known as JR on “Faces Places,” a road movie that featured the two of them roaming rural France, meeting the locals, celebrating them with enormous portraits and forming their own fast friendship. Among its many honors was an Academy Award nomination for best documentary feature. (It did not win, but that year Ms. Varda was given an honorary Academy Award for lifetime achievement.)

It was her early dramatic films that helped establish Ms. Varda as both an emblematic feminist and a cinematic firebrand — among them “Cléo From 5 to 7” (1962), in which a pop singer spends a fretful two hours awaiting the result of a cancer examination, and “Le Bonheur” (1965), about a young husband’s blithely choreographed extramarital affair.

Ms. Varda established herself as a maverick cineaste well before such milestones of the New Wave as Mr. Truffaut’s “The 400 Blows” (1959) and Mr. Godard’s “Breathless” (1960). Her “La Pointe Courte” (1955), which juxtaposed the strife of an unhappy couple with the struggles of a French fishing village, anticipated by several years the narrative and visual rule-breaking of directors like Mr. Truffaut, Mr. Godard and Alain Resnais, who edited “La Pointe Courte” and would introduce Ms. Varda to a number of the New Wave principals in Paris.

These included Mr. Truffaut, Mr. Godard, Claude Chabrol and Éric Rohmer, all of whom had gotten their start at the critic André Bazin’s magazine Cahiers du Cinema, and who became known as the Right Bank group. The more politicized and liberal Left Bank group would come to include Mr. Resnais, Chris Marker and Ms. Varda herself.

Arlette Varda was born on May 30, 1928, in Ixelles, Belgium, the daughter of a Greek father and a French mother. She left Belgium with her family in 1940 for Sète, France, where she spent her teenage years. At 18, she changed her name to Agnès.

She studied art history at the École du Louvre and photography at the École des Beaux-Arts before working as a photographer at the Théâtre National Populaire in Paris.

“I just didn’t see films when I was young,” she said in a 2009 interview. “I was stupid and naïve. Maybe I wouldn’t have made films if I had seen lots of others; maybe it would have stopped me.

“I started totally free and crazy and innocent,” she continued. “Now I’ve seen many films, and many beautiful films. And I try to keep a certain level of quality of my films. I don’t do commercials, I don’t do films pre-prepared by other people, I don’t do star system. So I do my own little thing.”

Her “thing” often involved straddling the line between what was commonly accepted as fiction and nonfiction, and defying the boundaries of gender.

“She was very clear about her feeling that the New Wave was a man’s club and that as a woman it was hard for producers to back her, even after she made ‘Cléo’ in 1962,” T. Jefferson Kline, a professor of French at Boston University and the editor of “Agnès Varda: Interviews” (2013), said in an interview for this obituary. “She obviously was not pleased that as a woman filmmaker she had so much trouble getting produced. She went to Los Angeles with her husband, and she said when she came back to France it was like she didn’t exist.”

Ms. Varda was married to the director Jacques Demy (“Lola,” “The Umbrellas of Cherbourg”) from 1962 until his death in 1990. From 1968 to 1970 they lived in Hollywood, where Mr. Demy made “Model Shop” for Columbia Pictures and Ms. Varda made “Lions Love,” which married a meditative late-’60s Los Angeles aesthetic to the New York counterculture. (The cast included the Warhol “superstar” Viva; Gerome Ragni and James Rado, the writers of the book for the musical “Hair”; and the underground filmmaker Shirley Clarke.) During that same period, she shot the short documentary “Black Panthers” (1968), which included an interview with the incarcerated Panther leader Huey Newton; commissioned by French television, it was suppressed at the time.

It was also during that period that she befriended Jim Morrison, the frontman of the Doors, who visited her and Mr. Demy in France; according to Stephen Davis’s “Jim Morrison: Life, Death, Legend” (2004), she was one of only five mourners at Mr. Morrison’s funeral in the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris in 1971. That same year she became one of the 343 women to sign the “Manifesto of the 343,” a French petition acknowledging that they had had abortions and thus making themselves vulnerable to prosecution.

In 1972, the birth of her son, Mathieu Demy, now an actor, prompted Ms. Varda to sideline her career. He survives her, as does the costume designer Rosalie Varda Demy, Ms. Varda’s daughter from a previous relationship, who was adopted by Jacques Demy.

“Despite my joy,” Ms. Varda told the actress Mireille Amiel in a 1975 interview, “I couldn’t help resenting the brakes put on my work and my travels.” So she had an electric line of about 300 feet for her camera and microphone run from her house, and with this “umbilical cord” she managed to interview the shopkeepers and her other neighbors on the Rue Daguerre. The result was “Daguerréotypes” (1976).

In 1977 she made what she called her “feminist musical,” and one of her better-known films, “One Sings, the Other Doesn’t,” which also seemed inspired by personal circumstance.

“It’s the story of two 15-year-old girls, their lives and their ideas,” she told Ms. Amiel. “They have to face this key problem: Do they want to have children or not? They each fall in love and encounter the contradictions — work/image, ideas/love, etc.”

One of Ms. Varda’s more controversial films, because of its casting, was “Kung-Fu Master!” (1988), a fictional work about an adult woman — played by the actress Jane Birkin, a friend of Ms. Varda’s — who falls in love with a teenage boy, played by Ms. Varda’s son. The title — it was changed in France to “Le Petit Amour” — referred to the young character’s favorite arcade game. The film was shot more or less simultaneously with “Jane B. par Agnes V.,” another of Ms. Varda’s border crossings between fact and fiction, which she called “an imaginary biopic.”

After Jacques Demy’s death, Ms. Varda made three films as a tribute: the biographical drama “Jacquot de Nantes” (1991) and the documentaries “Les Demoiselles Ont Eu 25 Ans” (1993), about the 25th anniversary of Mr. Demy’s “The Young Girls of Rochefort,” and “L’Univers de Jacques Demy” (1995).

Ms. Varda was then relatively inactive until 1999, when, armed for the first time with a digital camera, she set about making “Les Glaneurs et la Glaneuse” (“The Gleaners and I”), which resurrected an artistic career now well accustomed to under appreciation and resuscitation.

“She was a person of immense talent, but also enormously thoughtful,” said Mr. Kline of Boston University. “When you look at some of the films you might think they were more spontaneous than thought out. A film like ‘Cléo,’ for instance, you might have said, ‘O.K., she just follows Cléo around Paris,’ but the film is extremely beautifully imagined and thought out beforehand.”

In “Vagabond,” an 1985 film in which Sandrine Bonnaire plays a woman who is found dead and whose life is recounted, often in documentary style, “the traveling shots in the film are always ending, and each subsequent shot beginning, on a common visual cue,” Mr. Kline said. “It makes you look at film in a completely different way.”

Alison Smith, author of the critical study “Agnès Varda” (1998), called Ms. Varda “a poet of objects and how we use them.” In an interview for this obituary, she added, “Varda as an artist intrigued, and intrigues, me by the constant freshness and curiosity which she brings to her inquiries into the everyday world and how we relate to it, particularly how she uses the detailed fabric of life.”

Richard Peña, who as director of the New York Film Festival helped introduce “Gleaners” to an American audience, praised that film and Ms. Varda’s “The Beaches of Agnès” (2008) as “touchstones for a new generation of nonfiction filmmakers.”

Ms. Varda is represented at the Museum of Modern Art by photographs, films, videos and a three-screen installation titled “The Triptych of Noirmoutier.” “A decision to change direction and move into installation art when over 80 is, by any standards, remarkable,” Ms. Smith said. “But her energy was awe-inspiring.”

Phroyd

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

LE SIGNE DU LION - (Éric Rohmer, 1959).

The directorial debut of Rohmer in a full feature movie (produced by Claude Chabrol) can be viewed as a sort of personal “Reflection about Chance” that anticipates some of his future movies (I think of “La Boulangère de Monceau”, “Compte d’Hiver” and others); here the protagonist is a puppet completely in the hands of fate (either favorable or adverse) and in his sudden fortune, more than the opportunity of a redemption, one can sense an obscure menace.

The story is about a 40-year-old American who lives in Paris by sponging off his working friends and various wealthy acquaintances. When he receives a telegram saying that his wealthy aunt has died, he throws a party (using borrowed money of course) and invites all his friends but soon he discovers that his aunt disinherited him; briefly: his luggage is impounded and he is thrown out of his apartment. None of his friends are available so he is forced to wander the streets and become a vagabond... but another surprise is on arrival.

Narratively, I consider this emblematic film, more than a moral tale, a cautionary anecdote while, on the side of the mise-en-scène I see much of the French nouvelle vague in the sequences in which the (temporarily) desperate hero walks among the Quartier Latin and its iconic amused fauna uselessly calling for a loan without realising he is gradually becoming a clochard. Beyond the man’s private story, the film is also a precise documentary on Paris, with the city turning into a stone prison that gradually crushes resistance until the unfortunate hero suffers total moral and physical disintegration. I could say, in this regard, that the movie is truly one (of the few) “declaration of hate” to Paris viewed as a dirty, sunny, hostile city where also its raw marbles and its mellifluous waters seem to conspire against the lonely, abandoned, man.

r.m.

R.M.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Violette Nozière (Claude Chabrol, 1978)

No puede decirse que la distribución en España de las películas de Chabrol esté contribuyendo a la comprensión de su carrera, ya que la vamos conociendo fragmentariamente, con lagunas graves —por limitarnos a los últimos diez años, aún no han llegado La rupture (1970), Nada (1974), Les magiciens (1975)... —, en el más absoluto desorden, con retraso casi siempre, a veces en malas condiciones y ahora, para acabar de fastidiar con títulos idiotas (Laberinto mortal para Blood Relatives / Les liens de sang, 1977) o vergonzosos (como el que aflija a Violette Nozière, 1977 también, pero posterior). Esto, que es siempre molesto, resulta particularmente incómodo con una obra tan irregular y abundante como la de Chabrol, ya que a los desconcertantes virajes y altibajos del autor se suman o se mezclan los que artificialmente crea su caótica llegada hasta nosotros.

En 1971, Chabrol llevaba tres años y medio de gran actividad, en los que había rodado seis películas claramente relacionadas entre sí, con el mismo equipo técnico y repitiendo a menudo actores y hasta nombres de personajes. Se trata de lo que se ha llamado «tercera etapa» de su carrera, que comprende Les Biches (Las ciervas), La femme infidèle (La mujer infiel, 1968), Que la bête meure (Accidente sin huella), El carnicero (Le boucher, 1969) y La rupture, y culmina, a mi juicio, con Juste avant la nuit (Al anochecer, 1971). Parecía que, gracias al productor André Génovès y al notable éxito crítico y comercial de estas películas, Chabrol había conseguido una espléndida madurez y un dominio creciente de la narración y la dirección de actores. Pero en ese mismo año, Chabrol realiza un proyecto que se había ido retrasando por compromisos o enfermedades de los actores previstos, La décade prodigieuse (La década prodigiosa), un film a mitad de camino entre Chesterton (El hombre que fue jueves) y Orson Welles (Mr. Arkadin) que, pese a ser admirable, suponía una clara ruptura con las películas precedentes y desconcertó al público y a la crítica en general. A partir de entonces, Chabrol parece estar buscando un nuevo rumbo sin acabar de encontrarlo; cada cierto tiempo, ante el fracaso de sus intentos de renovación, vuelve —a veces con fortuna, como en Les noces rouges (Relaciones sangrientas, 1973) y, sobre todo, Une partie de plaisir (Una fiesta de placer, 1974); otras, con menor acierto y un tratamiento entre caricaturesco y paródico, como en Les innocents aux mains sales (Inocentes con manos sucias, 1975) y Folies bourgeoises / The Twist (Locuras de un matrimonio burgués, 1976)— al terreno de sus mejores obras. Cada tentativa de hallar un nuevo camino, ya sin Génovès, y con actores muy diferentes —tanto Michel Bouquet como Stéphane Audran pierden importancia o desaparecen—, suele ser un fracaso de taquilla y de crítica, comprensible, a mi modo de ver, cuando el resultado es tan deplorable como Dr. Popaul (Dr. Casanova, 1972), inexplicable cuando se trata de films tan apasionantes como Alice ou la dernière fugue (Alicia o la última fuga, 1976) o Blood Relatives.

El caso es que Chabrol parece un tanto perdido, y su prestigio —rápidamente ascendente de 1968 a 1971— cae en picado, hasta que se olvidan sus obras maestras y se deja, prácticamente, de «contar con él». Alternando películas más o menos personales y conseguidas con buen número de trabajos para televisión e incluso con la realización de algún «spot» publicitario, Chabrol sigue trabajando sin parar, y sin que sus films llamen la atención hasta la presentación, en el festival de Cannes de 1978, de Violette Nozière.

Para algunos, Chabrol se ha reencontrado en esta película; es posible, pero pienso que, en todo caso, lo ha hecho con quince años de retraso: Violette Nozière tendría sentido, en la obra de Chabrol, justo antes o después de Landru (Landrú, 1962); no, creo yo, después de Juste avant la nuit, Une partie de plaisir o Alice ou la dernière fugue. Lo mismo ocurre, en ciertos aspectos —construcción en «flashbacks», estructura familiar opresiva, crimen provocado por los celos, investigador «distanciado»— con Blood Relatives, que enlaza directamente con Les cousins (Los primos, 1958), À double tour (Una doble vida, 1959) y Ophélia (Ofelia, 1962), pero, al menos, lo hace con un mayor dominio de la puesta en escena, en Montreal y con un estilo «americano» que supone una notable diferencia. Violette Nozière es una reconstrucción histórica de una célebre causa real, un film de época, construido en torno al proceso y narrado muy fragmentariamente, con breves y frecuentes «flashbacks» e «imaginaciones», y siguiendo constantemente a un personaje central, el del asesino «anarquista»; todo ello como en Landrú, pero con un par de diferencias que, a mi modo de ver, no representan progreso alguno, sino todo lo contrario.

Landrú era un film voluntaria y deliberadamente teatral, distanciado y lleno de humor, Violette Nozière, por el contrario, opta por el naturalismo preciosista del cine «retro» —un poco como Bertolucci en Il conformista (El conformista, 1970) o Visconti en La caduta degli dei/Götterdämmerung (La caída de los dioses, 1969), por poner ejemplos respetables—, Chabrol pretende «haberse enamorado» —nada menos— de Violette, y hace un film enormemente pesado y solemne, sin el menor sentido del humor. Para colmo, frente a la admirable y estrafalaria caracterización de Charles Denner como Landru, en Violette Nozière nos encontramos a Isabelle Huppert repitiendo por enésima vez su papel de siempre, con esa inexpresividad poco inteligente y nada enigmática que lo mismo le sirve para hacer de asesina que de ingenua o víctima (La dentellière, Le juge et l'assassin, Les indiens sont encore loin, etc.). En lugar de un reparto integrado por los mejores secundarios (y varias estrellas) del cine francés del momento, Chabrol nos obsequia con las peores interpretaciones que pueden hallarse en su obra —Jean-François Garreaud sobre todo—, desaprovecha a su ex-mujer y a Jean Carmet al encomendarles personajes esquemáticos y al mismo tiempo confusos; y todo ello, además, en un sentido inesperado: si su dirección de actores fallaba era, a veces, por exceso, por afición al histrionismo y a las muecas, y no, como en Violette Nozière, por sosería generalizada.

Lo más grave es que, además, Violette Nozière es una película mal construida y deficientemente narrada; más que de Chabrol parece de Bertrand Tavernier: no sólo el proyecto en si, su supuesto carácter «reivindicativo», la desangelada frialdad del conjunto y los fallos de estructura hacen pensar en Le juge et l'assassin, sino hasta el haber recurrido —como guionista— a Hervé Bromberger parece afán de reenlazar con une certaine tendence du cinéma français que denunció enérgicamente Truffaut en 1954 y que también Chabrol calificaba por entonces de cinéma de qualité. Lo que, afortunadamente, separa a Chabrol del autor de L'horloger de St. Paul es que el primero es mucho mejor director, y que eso se nota, de vez en cuando, en alguna secuencia, a menudo en planos sueltos admirablemente encuadrados y con una dinámica interna que no está al alcance de cualquiera, en gestos aislados, captados con reveladora precisión, en un uso del espacio —sobre todo en el interior del apretujado piso de los Nozière, que produce auténtica claustrofobia— que remite al Renoir de La chienne (1931), Toni (1934) o Le crime de Monsieur Lange (1935) y al Fritz Lang de M (1931); estos ratos, lamentablemente no muy frecuentes, discontinuos, dispersos en un conjunto casi ramplón al mismo tiempo que demasiado cuidado como para llegar a tener vida —y en eso no hay nada tan opuesto al Renoir de los años 30 como Violette Nozière—, es decir, casi ahogados por el academicismo, revelan inequívocamente la presencia de un director capaz de hacer cosas muy superiores, lo que serviría, al menos, para que no perdiésemos del todo la esperanza los admiradores de Chabrol. Por suerte, unos meses antes habla realizado Blood Relatives, su primera película «americana», y en ella demuestra que, si quiere, puede estar en plena forma, y hacer todavía películas inquietantes y emocionantes, y no confusas y gélidas ilustraciones de archivo o de museo de cera.

Miguel Marías

Revista “Dirigido por” nº71, marzo-1980

1 note

·

View note