#robert propst

Text

0 notes

Text

The Evolution of Office Interior Design: From Traditional to Modern Workspaces

In today's fast-paced and ever-changing business world, the design of office spaces plays a crucial role in shaping the way we work and interact with our environment. Office interior design has evolved significantly over the years, reflecting changes in work culture, technology, and our understanding of human psychology. In this blog, we will explore the fascinating journey of office interior design, from traditional to modern workspaces, and examine the key factors driving this evolution.

The Roots of Office Interior Design

The concept of office interior design dates back to ancient times when civilizations like the Egyptians and Greeks built administrative centres. These early offices focused primarily on functionality, with little consideration for aesthetics or employee well-being. Offices were often austere and rigid, featuring rows of desks and minimal personalization.

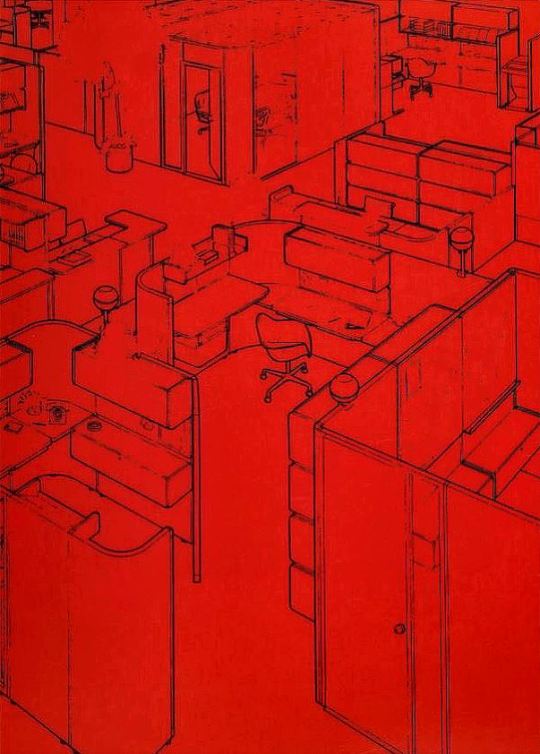

The Birth of the Cubicle Farm

The 20th century brought about significant changes in office interior design. One of the most iconic developments during this time was the advent of the cubicle farm. Introduced by Robert Propst in the 1960s and popularised by Herman Miller, the cubicle sought to create a sense of privacy and personal space for employees. This design concept aimed to improve productivity and minimise distractions. However, it quickly became synonymous with monotonous and uninspiring work environments.

The Traditional Office

Prior to the rise of the cubicle farm, traditional office spaces were marked by private offices for senior executives and open bullpens for other employees. These designs emphasised hierarchy and rigid structures, often neglecting the needs of individual employees. The focus was on order and control, with little regard for employee comfort and well-being.

Traditional office interiors were dominated by dark wood furnishings, imposing desks, and high-backed leather chairs. The atmosphere was formal, and personalization was discouraged. Natural light was often limited, leading to a stark and uninviting environment.

The Shift Towards Open Offices

In the late 20th century and early 21st century, a new trend emerged: the open office. This design philosophy aimed to foster collaboration, communication, and creativity among employees. Open offices removed walls, partitions, and individual offices, favouring shared workspaces. The intention was to create a more egalitarian and dynamic work environment.

Open offices often featured communal tables, low partitions, and a vibrant colour scheme. These designs encouraged employees to interact more freely and share ideas. However, while open offices had their merits, they also brought about their own set of challenges. Noise levels, lack of privacy, and distractions became common issues that needed to be addressed.

The Modern Office Interior Design

The modern office interior design represents a culmination of these historical developments and a response to the needs and preferences of the contemporary workforce. It seeks to strike a balance between individual comfort and collaboration, as well as aesthetics and functionality.

Key Features of Modern Office Interior Design

Flexibility: Modern office spaces are highly adaptable. Furniture and layouts can be rearranged to accommodate different work styles and tasks. This adaptability aligns with the changing nature of work and the need for agile spaces.

Comfort and Well-being: The well-being of employees is a central consideration in modern office design. Ergonomic furniture, ample natural light, and green spaces are incorporated to enhance comfort and productivity. Biophilic design, which incorporates elements of nature, is increasingly popular.

Collaborative Zones: Modern offices include designated spaces for collaboration, such as meeting rooms, huddle areas, and open lounges. These areas provide employees with options for team meetings, brainstorming sessions, and informal discussions.

Technology Integration: Technology is seamlessly integrated into the modern office. This includes advanced communication tools, wireless charging stations, and smart lighting systems that can be controlled through mobile apps.

Personalization: While the traditional office discouraged personalization, modern office design encourages employees to make their workspace their own. Personal touches like plants, artwork, and unique desk setups are common.

Acoustic Solutions: To combat noise issues in open office environments, modern designs incorporate acoustic panels, soundproof booths, and noise-cancelling systems. This ensures that employees can work in a quieter and more focused atmosphere.

Sustainability: Modern office interior design often prioritises sustainability. This includes the use of eco-friendly materials, energy-efficient lighting, and waste reduction strategies. Green certifications like LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) are highly sought after.

Brand Identity: Modern offices are designed to reflect a company's brand and values. Colours, logos, and visual elements that align with a company's identity are thoughtfully integrated into the design.

Hybrid Workspaces: With the advent of remote work and the hybrid work model, modern office interior design incorporates spaces that cater to both in-office and remote employees. This includes video conferencing rooms and flexible workstations.

Source Link : https://addindiagroup.com/the-evolution-of-office-interior-design-from-traditional-to-modern-workspaces/

0 notes

Text

Office Cubicles

The office cubicle, which has come to symbolize the corporate world, has had a complicated ride over the years.

While today's office spaces develop in response to shifting work philosophies and technology breakthroughs, the cubicle remains a focal focus of conversation and reflection on how the workplace affects employee well-being, productivity, and collaboration.

Robert Propst, a designer for Herman Miller, a well-known furniture design company, pioneered the 'Action Office' in the 1960s. Contrary to popular opinion, Propst's first design was not a monotonous sea of cubicles. He intended to design a versatile workspace that accommodated both seclusion and collaboration.

0 notes

Link

HEROES & FRIENDS TRIBUTE TO RANDY TRAVIS’ ANNOUNCED FOR TUESDAY, OCTOBER 24, 2023, AT 7:00 PM AT HUNTSVILLE’S VBC PROPST ARENA Photo Credit: Robert Trachtenberg Artist lineup to be announced soon! Portion of Proceeds to

0 notes

Photo

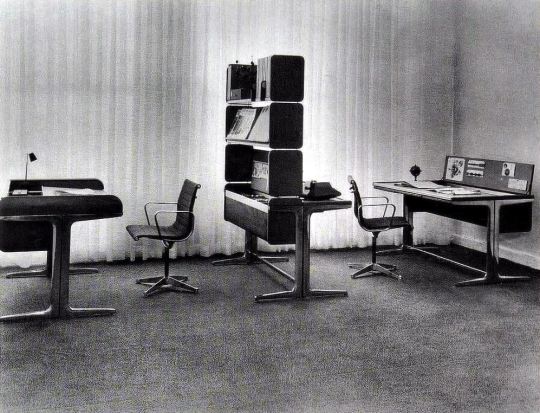

Herman Miller’s “Action Office” designed by Robert Propst. 1964.

#robert propst#vintage office decor#herman miller#space age#1960s interior#vintage office furniture#design#1960s#1964

421 notes

·

View notes

Text

There Ain’t ‘Alf Some Clever Bastards – Part One Hundred and Five

There Ain’t ‘Alf Some Clever Bastards – Part One Hundred and Five - Robert Propst, the inventor of the cubicle office configuration, much to his regret

Robert Propst (1921 – 2000)

An inventor has many obstacles to overcome to bring their idea to fruition. But even when it has seen the light of day and made their fame and fortune, they may be struck by another problem, something that might be characterised as inventor’s remorse. They have released a genie from the bottle and wish that they had let things be. One such, whom I featured in my…

View On WordPress

#Action Office#Action Office 2#Fifty Clever Bastards#Herman Miller#Martin Fone#office cubicles#Robert Propst#The Fickle Finger#Walter Hunt

0 notes

Photo

Source: http://twitter.com/99piorg/status/932670797893775360

Office Space Time Loop: From Open Plans to Cubicle Farms and Back Again https://t.co/eXS1CCwdBj http://pic.twitter.com/Y4ZrF0HNia

— 99 Percent Invisible (@99piorg) November 20, 2017

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

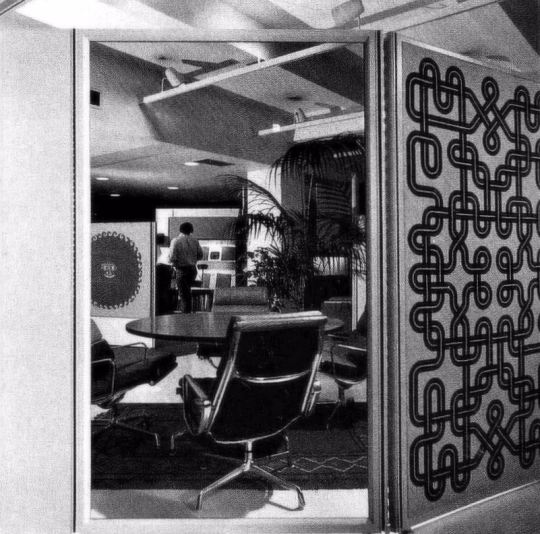

By the middle of the 20th century, the name Herman Miller had become synonymous with “modern” furniture. Working with legendary designers George Nelson and Charles and Ray Eames, the company produced pieces that would become classics of industrial design.

Since then, they collaborated with some of the most outstanding designers in the world, including Alexander Girard, Isamu Noguchi, Robert Propst, Bill Stumpf, Don Chadwick, Ayse Birsel, Studio 7.5, Yves Béhar, Doug Ball, and many talented others.

Herman Miller is a recognized innovator in contemporary interior furnishings

Herman Miller design is now available on Rockerpalm https://www.rockerpalm.com/running-campaigns/herman-miller.html

#hermanmiller#design#homeliving#buy#in#crypto#luxury#luxuries#chair#furniture#home & lifestyle#goodlife#rockerpalm#best#designer#alexander girard#isamu noguchi#robert propst#bill stumpf#and#follow for more#fashion#cryptocurrency#millionaire#billionaire#joinus

0 notes

Photo

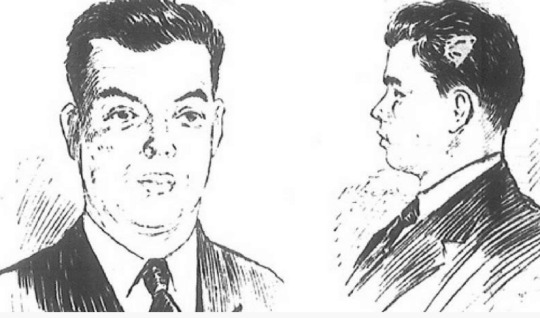

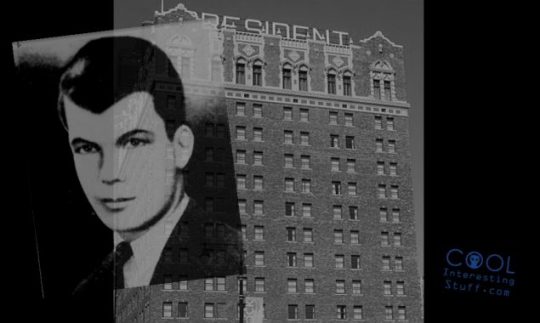

The Long and Confusing Murder of Artemus Ogletree/Roland T Owen

Early on the afternoon of January 2, 1935, Ogletree walked into the Hotel President, in what is now the Power & Light District of Kansas City, Missouri, and asked for an interior room several floors up, giving his name as Roland T. Owen, with a Los Angeles address. Staff remembered him as dressed well and wearing a dark overcoat; he brought no bags with him. Ogletree paid for one night. The staff noted that in addition to the visible scar on his temple, he had cauliflower ear, and concluded he was probably a boxer or professional wrestler. They believed him to be in his early 20s.

Randolph Propst, a bellhop, accompanied Ogletree up in the elevator to the 10th floor. On the way, Ogletree told him that he had spent the previous night at the nearby Muehlebach Hotel but found the nightly rate too high. Propst opened Room 1046, which per the guest's request was on the inside, overlooking the hotel's courtyard rather than the street outside. He watched as Ogletree took a hairbrush, comb and toothpaste from his overcoat pocket, the extent of his unpacking. After Ogletree put those items above the sink, he and Propst left the room. The bellboy returned to lock it, and gave Ogletree the key.

After returning to the lobby, he saw Ogletree leave the hotel. A short time afterward, Mary Soptic, one of the hotel maids, returned from a day off to work the afternoon shift. She went into Room 1046 and was surprised to find Ogletree there, since the previous night a woman had been in the room. She apologized, but he said she could go ahead and clean the room. While she did, she noticed that he had the shades drawn and left only one dim lamp on. This would remain the case when she encountered Ogletree in the room on other occasions during his stay. "He was either worried about something or afraid" in addition to this preference for low light, she told police later. After she had been cleaning for a few minutes, Ogletree put his overcoat on and brushed his hair. He then left, but asked her to leave the room unlocked as he was expecting some friends in a few minutes. Soptic did as he asked. At 4 p.m., she returned to the room with freshly laundered towels. Inside, the room was dark. She saw Ogletree lying on the bed, fully dressed. Visible in the light from the hallway was a note on his bedside table that read "Don: I will be back in fifteen minutes. Wait".

The next morning, Soptic returned to Room 1046 around 10:30. The door was locked, which led her to assume that Ogletree was out since it could only be locked from the outside, but when she opened it with her own key Ogletree was present, sitting in the dark just where he had been the previous afternoon. The phone rang and he answered it. "No, Don, I don't want to eat. I am not hungry. I just had breakfast ... No, I am not hungry", he said. Still holding the phone, Ogletree asked Soptic about her job as she cleaned. He wanted to know if she was responsible for the entire floor, and if the President was residential. He repeated his complaint about the Muehlebach's exorbitant rates, after which she finished cleaning, and left. Again at 4 p.m., Soptic returned with fresh towels. Inside Room 1046, she could hear two men talking, so she knocked. A voice she described as loud and deep, probably not Ogletree's, asked who it was. She responded that she had brought fresh towels, to which the voice said "We don't need any". Yet Soptic knew there were no towels in the room, as she had taken them herself in the morning.

At 11 p.m. Robert Lane, a city worker driving on 13th Street near Lydia Avenue, saw a man dressed in only an undershirt, pants and shoes run into his path and flag him down. When Lane stopped, the man apologized, saying he had taken Lane's car for a taxi. The man asked Lane if he could take him to somewhere he might be able to get a taxi. Lane agreed and let the man in. "You look as if you've been in it bad", he observed; the man swore he would kill someone else tomorrow, presumably in retaliation for whatever had been done to him. In the mirror Lane saw a deep scratch on the man's arm; he also noticed that he was cupping his arm, possibly to catch blood from a more severe wound. At the nearby intersection of 12th Street and Troost Avenue, where taxi drivers often waited for fares during the overnight hours, Lane stopped and let the man out. The man thanked him, got out, and honked the horn of a taxi parked nearby, drawing the driver from a nearby restaurant, after which Lane drove away. After Ogletree's death, Lane went to view the body. He saw the same scratch on the arm and went to the police, telling them he believed Ogletree had been the man he picked up.

At 7 a.m., a new switchboard operator, Della Ferguson, came on shift. She was preparing to make a requested wakeup call to Room 1046 when she noticed a light indicating that the phone there was off the hook. Propst, who had led Ogletree there two days earlier, was on shift again and drew the assignment. The door to Room 1046 was locked, with a "Do Not Disturb" sign hanging from the doorknob. After several loud knocks, a voice from inside told him to enter; however he could not as the door had been locked. The same voice told him, after another knock, to turn on the lights, but he still could not enter. Finally, Propst just shouted through the door to hang the phone up, and left. Propst told Ferguson that the guest in Room 1046 was probably drunk and she should wait another hour. At 8:30 a.m., the phone had still not been hung up. Another bellboy, Harold Pike, was sent to the 10th floor. The "Do Not Disturb" sign was still on the door, and it was still locked, but Pike had a key and let himself in. Inside he found Ogletree in the dark, lying on the bed naked, apparently drunk. The light from the hallway showed some dark spots on the bedding, but rather than turn on the room light Pike went to the telephone stand, where he saw the phone had been knocked to the floor. He put it back on the stand, replacing the handset. Shortly after 10:30 a.m., another operator reported that the phone in Room 1046 was once again off the hook. Again Propst was sent to the room to see what was going on; the "Do Not Disturb" sign remained on the knob. This time he had a key, and after his knocks drew no response, he opened the door and found Ogletree on his knees and elbows two feet (60 cm) away, his head bloodied. Propst turned the light on, put the phone back on the hook, and then noticed blood on the walls of both the main room and bathroom, as well as on the bed itself.

Propst went downstairs immediately for help. He returned with the assistant manager, but when they did they could only open the door six inches (15 cm), as Ogletree had in the interim fallen on the floor. Eventually Ogletree got up and when the two hotel employees were able to enter the room, he went and sat on the edge of the bathtub. The assistant manager called the police; they were joined by Dr. Harold Flanders of Kansas City General Hospital. Ogletree had been bound with cord around his neck, wrists, and ankles. His neck had further bruising, suggesting someone had been attempting to strangle him. He had been stabbed more than once in the chest above the heart; one of these wounds had punctured his lung. Blows to his head had left him with a skull fracture on the right side. In addition to the blood Propst had seen, there was some additional spatter on the ceiling. Dr. Flanders cut the cords from Ogletree's wrist and asked him who had done this to him. "Nobody", Ogletree answered. Asked, then, what had caused these injuries, he said he had fallen and hit his head on the bathtub. The doctor asked if he had been trying to kill himself. After saying no, Ogletree lost consciousness and was taken to the hospital. He was completely comatose by the time he arrived and died shortly after midnight on January 5.

The case returned to the newspapers on March 3, when the funeral home where the body had been kept announced it would be burying the man in the city's potter's field the next day. That day, the funeral home received a call from a man who asked that the funeral be delayed so they could send the funeral home the money for a grave and service at Memorial Park Cemetery in Kansas City, Kansas, so, the caller said, the dead man would be near his sister. The funeral director warned the caller he would have to tell the police about the call; the caller said he knew and that did not bother him.

The caller was slightly more forthcoming when the funeral director asked why Ogletree had been killed. According to the caller, Ogletree had had an affair with one woman while engaged to marry another. The caller and the two women had apparently arranged the encounter with him at the President in order to exact revenge. "Cheaters usually get what's coming to them!" the caller said, and hung up.

The service was postponed per the anonymous caller's request. On March 23, the funeral home received a delivery envelope, the address carefully lettered using a ruler with $25 ($500 in current dollars) wrapped in newspaper; it was enough to cover the expenses. The sender was unknown.

Two additional envelopes with $5 each were sent to a local florist for an arrangement of 13 American Beauty roses to go with the grave, after a similar call was made to them; both phone calls turned out to have been made from pay phones. Included with this payment was a card, with disguised handwriting, reading "Love Forever – Louise". The funeral was held shortly afterwards. Besides the officiating minister, the only attendees were police detectives, some of whom served as pallbearers. Other detectives, posing as gravediggers, staked out the grave for the next several days, but no one came to visit.

Several days after the funeral, a woman called the Kansas City Journal-Post's newsroom to inform them that their earlier story that the dead man from Room 1046 would be buried in a pauper's grave was incorrect, that he had in fact been given a formal funeral. She said the funeral home and flower shop could verify this. Asked to identify herself, she said "Never mind, I know what I'm talking about", Pressed for what that was, she responded, "He got into a jam", and ended the conversation.

70 notes

·

View notes

Photo

April 28th is...

Biological Clock Day - Both men and women have a biological clock, and it affects their behaviour and mood on a daily basis. It maintains a sleep-wake pattern that fits in with the light and dark of a day on Earth. More formally known as the circadian rhythm, it monitors light, temperature and other environmental factors to influence things like alertness, energy levels, hunger and motivation.

Blueberry Pie Day - Blueberries, or star berries as the Native Americans call them, are one of nature’s superfoods. Rich in antioxidants and vitamins, and extremely healthy, blueberries are one of nature’s many good gifts that humans can use to create a myriad of delicious recipes!

Clean Comedy Day - While it’s true that comedy is often built on the back of crossing societal norms and humorously presenting these situations, it isn’t always necessary to spout profanity as part of a comedy routine. Some of the best comedy in the world is based on absurdity, and the absurd need not be bawdy.

Cubicle Day - It presents an opportunity for departmentalized office workers to rise above the conformist standards, customize their cubes and announce their individuality. Designed by Robert Propst and known for a complete absence of individuality, cubicles were first introduced in 1967 as a way to subdivide open office space and provide workers with a degree of privacy.

Guide Dogs Day - Guide dogs have been around since the 79 AD when paintings of guide dogs being used to help the blind was seen at the excavations in Pompeii. This day honors the work that these service dogs provide for people everywhere. These dogs have skills ranging from leading a blind person around an area to providing emotional comfort during their service.

Pay It Forward Day - The aim of the day is to make a difference by doing a kind act. The hope is that this will have a ripple effect, with kindness being felt across the globe.

Shrimp Scampi Day - It turns out there’s actually quite a number of different varieties depending on where in the world you are. It all comes down to what, precisely, scampi is. Scampi, as it turns out, is the name given to Nephrops Norvegicus, otherwise known as the Norway lobster. But in the US it’s also the common name for shrimp when served as part of Italian-American food in the states. British Scampi appears to be served as a form of fish-and-chips, with the Nephrops Norvegicus being served battered and fried.

Stop Food Waste Day - Today, 45% of root crops, fruit, and vegetables produced globally are wasted per year as well as 33% of all food produced globally. With those percentages, there is a significant food waste epidemic that people are globally facing.

Superhero Day - The first fictional superhero stories were published in a comic strip in 1936 (Phantom), then in 1940 a female counterpart was introduced (Fantomah), and since then hundreds of them have been created and developed. Other kinds of superheroes are out there in the world, who are probably less obvious but no less important. These are the heroes who wear Firemen’s Uniforms or Police Uniforms, those that drive ambulances or Medivac Helicopters. Or, sometimes they just wear the clothes of mother or father hard at work.

Workers’ Memorial Day - We often forget to take the time to remember that there were amazing people and lives that went into building the structure of the society we live in. It wasn’t that long ago that everything from the clothes we wear to the buildings we inhabit were built in highly dangerous conditions lacking the rules and regulations that serve to keep workers safe in modern industry. Workers’ Memorial Day commemorates the lives that have been given in the pursuit of modern comfort and convenience, and stands for the worldwide efforts to create safety in the workplace.

#biological clock#blueberry pie#comedy#cubicles#guide dogs#pay it forward#shrimp scampi#food waste#superhero#woekers memorial

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Action Office" Wall-Mounted Desk, George Nelson, 1964, Art Institute of Chicago: Architecture and Design

In the 1960s, Herman Miller designers George Nelson and Robert Propst set out to liberate white-collar workers from factorylike rows of desks and typewriters. Their solution was the Action Office, a suite of furniture that allowed the office worker to move among pieces well suited to each task, such as a standing desk and mobile meeting station. The system was colorful, well built, and dynamic, yet it was eventually redesigned after poor sales, leading to the creation of what we now know as the ubiquitous and dull cubicle. Gift of Allan Frumkin

Medium: Aluminum, plastic, and wood

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/158243/

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Pinkney Thomas “Junior” Mitchell, Jr Photo added by MJ Pinkney Thomas “Junior” Mitchell, Jr BIRTH 2 Jun 1949 DEATH 18 Dec 1997 (aged 48) BURIAL Bessemer City Memorial Cemetery Bessemer City, Gaston County, North Carolina, USA MEMORIAL ID 66861237 Justia › US Law › Case Law › North Carolina Case Law › North Carolina Supreme Court Decisions › 1975 › State v. Mitchell Receive free daily summaries of new opinions from the North Carolina Supreme Court. Enter your email. Enter your email. Subscribe State v. Mitchell Annotate this Case 218 S.E.2d 332 (1975) 288 N.C. 360 STATE of North Carolina v. Pinkney Thomas MITCHELL, Jr., and Wallace Charles Lanford, Jr. No. 7. Supreme Court of North Carolina. October 7, 1975. *335 Atty. Gen. Rufus L. Edmisten by Associate Attorney Robert W. Kaylor, Raleigh, for the State. Robert H. Forbes, Gastonia, for Pinkney Thomas Mitchell, Jr. and Robert E. Gaines, Gastonia, for Wallace Charles Lanford, Jr., representing defendant appellants. COPELAND, Justice. Defendants were represented by separate counsel and filed separate appeals. Some of the assignments of error are the same and some relate only to one defendant. Our Court has held that where there are two indictments in which both defendants are charged with the same crimes, then they may be consolidated for trial in the discretion of the court. State v. Combs, 200 N.C. 671, 674, 158 S.E. 252, 254 (1931). "The Court is expressly authorized by statute in this state to order the consolidation for trial of two or more indictments in which the defendant or defendants are charged with crimes of the same class, which are so connected in time or place as that evidence at the trial of one of the indictments will be competent and admissible *336 at the trial of the others. [Citations omitted.]" Id. at 674, 158 S.E. at 254. G.S. 15-152; State v. Dawson, 281 N.C. 645, 190 S.E.2d 196 (1972); State v. White, 256 N.C. 244, 123 S.E.2d 483 (1962). Defendant Mitchell contends the consolidation was prejudicial to him because of the testimony of William Richard Stewart, the brother-in-law of defendant Lanford. A careful examination of the record indicates that Stewart testified as to substantially similar incriminating statements made by each defendant in the presence of one another. In essence, Mitchell adopted Lanford's admissions to Stewart. Defendant Lanford contends that the consolidation was prejudicial against him because defendant Mitchell testified in his own behalf at the trial and attempted to mitigate the killing and reduce it to second-degree murder because of his use of drugs and intoxicants. Lanford contends that this especially hurt his case since he elected not to testify in his own behalf. There is absolutely nothing in the record to indicate that the trial judge in making his ruling on consolidation knew that Mitchell would take the witness stand. In any event, Mitchell had a right to testify if he wished and Lanford could cross-examine him. Moreover, it is difficult to understand how Lanford can contend that he was prejudiced by Mitchell testifying when in fact Mitchell admitted the killing and the burning of the vehicle and attempted by his testimony to exonerate Lanford in every way. It was proper and appropriate for the two defendants to be tried together and there is no merit to this assignment of error. Defendants Lanford and Mitchell next contend that the court should have dismissed the cases against them as of nonsuit and for mistrial for the charges of first-degree murder at the close of the State's evidence and at the close of all the evidence. Lanford makes a similar contention with respect to the charge of felonious burning of personal property. Upon a motion for nonsuit, the trial court must consider the evidence in the light most favorable to the State. The trial court is not concerned with the weight of the testimony, but only with whether the evidence, be it direct or circumstantial, supports sending the case to the jury. State v. McNeil, 280 N.C. 159, 185 S.E.2d 156 (1971); State v. Goines, 273 N.C. 509, 160 S.E.2d 469 (1968). Conflicts and discrepancies in the evidence should be resolved in the State's favor. State v. Cooper, 286 N.C. 549, 213 S.E.2d 305 (1975); State v. McNeil, supra; State v. Cutler, 271 N.C. 379, 156 S.E.2d 679 (1967). In order to convict the defendant of first-degree murder, the State must satisfy the jury beyond a reasonable doubt of all the elements thereof, to wit, an unlawful killing of a human being with malice and with a specific intent to kill and committed after premeditation and deliberation. "Of course, ordinarily, it is not possible to prove premeditation and deliberation by direct evidence. Therefore, these elements of first degree murder must be established by proof of circumstances from which they may be inferred. [Citations omitted.] Among the circumstances to be considered by the jury in determining whether a killing was with premeditation and deliberation are: want of provocation on the part of the deceased; the conduct of the defendant before and after the killing; the use of grossly excessive force; or the dealing of lethal blows after the deceased has been felled. [Citations omitted.]" State v. Buchanan, 287 N.C. 408, 420-21, 215 S.E.2d 80, 87-88 (1975); State v. Van Landingham, 283 N.C. 589, 197 S.E.2d 539 (1973); State v. Hamby and State v. Chandler, 276 N.C. 674, 174 S.E.2d 385 (1970); State v. Sanders, 276 N.C. 598, 174 S.E.2d 487 (1970); State v. Walters, 275 N.C. 615, 170 S.E.2d 484 (1969); State v. Faust, 254 N.C. 101, 118 S.E.2d 769 (1961). An analysis of the facts of the case in relation to these factors reveals a want *337 of provocation by the deceaseda sixteen-year-old girl. The conduct of defendants before and after the killing supported an inference of premeditation and deliberation as well as the other elements of the crimes charged. The State's evidence permits the following reasonable inferences: defendants abducted the victim and had sexual relations with her; defendants told Stewart that they had killed the victim; defendants later departed in the victim's automobile and burned it in order to destroy any evidence; and defendants secured another vehicle in which to leave Gaston County. The use of grossly excessive force was indicated when the deceased was found tied to a tree, gagged, and stabbed numerous times in vital areas of the body. In summation, there was plenary evidence as to both defendants from which to show premeditation and deliberation as well as the other elements of the crimes involved. This assignment of error is without merit and is overruled. Defendant Mitchell contends that the trial court committed error in the charge to the jury. Counsel for Mitchell, with commendable frankness, states that none of the exceptions, in his opinion, would entitle Mitchell to a new trial. Counsel requests the court to review the charge. This has been done and we conclude that there was no error. Defendant Mitchell contends the court erred in permitting the witness Shellnut to change his description of the defendants on voir dire. There was no voir dire of Shellnut and he did not identify defendants. There is no merit in this argument. Defendant Mitchell also contends that it was improper for the court to receive evidence concerning the home life of the deceased, photographs of the area in which she lived and where she was seen with the defendants, and photographs of the deceased, the automobile, and its contents. In connection with these assignments of error, counsel for the defendant concedes that none of these individually would entitle the defendant to a new trial, but should be considered reversible error when considered as a whole. All of this evidence, save that of the home life of the victim, was competent and relevant to establish the identification of the victim, the ownership of the Volkswagen, and the identification of the general area where the crimes had their inception. The photographic evidence was introduced with limiting instructions for the purpose of illustrating the testimony of the witnesses. State v. Atkinson, 275 N.C. 288, 167 S.E.2d 241 (1969). If the evidence pertaining to the home life of the deceased was error, then it was clearly harmless beyond a reasonable doubt. State v. Jones, 280 N.C. 322, 185 S.E.2d 858 (1972); Chapman v. California, 386 U.S. 18, 87 S. Ct. 824, 17 L. Ed. 2d 705 (1967). These assignments of error are overruled. Defendant Mitchell also contends that admission of the testimony of the witness Stewart was prejudicial error. As stated earlier in the discussion on consolidation, there is no merit in this related contention for the reasons there stated. A further contention of Mitchell is that the failure of Lanford to testify caused the jury to have grave doubts concerning Mitchell's defense. This argument has no merit. The record indicates that Mitchell by his own testimony admitted the killing and the burning of the Volkswagen and attempted to excuse himself of murder in the first degree because of the use of drugs and intoxicating beverages. Defendant Mitchell contends that he did not have sufficient mental capacity to form the necessary premeditation and deliberation. In this connection, the trial court properly charged the jury on the law relative to voluntary intoxication and voluntary use of drugs. It was properly left for the jury to determine whether Mitchell's mental condition was so affected by intoxication or drugs that he was rendered incapable of forming a deliberate and premeditated purpose to kill. State v. Propst, *338 274 N.C. 62, 161 S.E.2d 560 (1968). This assignment of error is overruled. Both defendants contend that the court erred by refusing to set the verdict aside as being against the greater weight of the evidence and refusing to declare a mistrial. These motions were addressed to the discretion of the trial court. That discretion was not abused. 3 Strong, N.C. Index 2d, Criminal Law, §§ 128, 132. As a matter of fact, we have fully considered this in the discussion on the motions for nonsuit. These assignments are without merit and are overruled. The defendants have had a fair trial free from prejudicial error. Kathy was sent to her death in a vicious manner by these defendants. The case was ably prepared and presented by the district attorney and carefully and fairly tried by Judge Grist. In the trial we find No error. North Carolina Supreme Court opinions.

Wallace Lanford and Pinkney Mitchell were convicted and received life sentences in Smiley's killing, and both have since died in a state prison.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Yes, the Open Office Is Terrible — But It Doesn’t Have to Be (Ep. 358 Rebroadcast)

Feeling stressed from working in a noisy open office? Tell your boss that working from home increases worker productivity by 13 percent! (Photo: MaxPixel)

It began as a post-war dream for a more collaborative and egalitarian workplace. It has evolved into a nightmare of noise and discomfort. Can the open office be saved, or should we all just be working from home?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast at Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, or elsewhere. Below is a transcript of the episode, edited for readability. For more information on the people and ideas in the episode, see the links at the bottom of this post.

* * *

Hey, are you at work right now? And do you work in an office? Have you ever worked in an office? If you have, there’s a good chance it was an open office, at least to some degree. The open office design has been around for decades, in a variety of forms. If you’re a cynic, you might think an open office is all about cramming the maximum number of employees into the minimum amount of real estate. But you could also imagine that an open office produces better interaction and more collaboration. Wouldn’t it be nice to know if this were true? That’s what these people wanted to learn.

Ethan BERNSTEIN: I’m Ethan Bernstein, I’m an associate professor of business administration at the Harvard Business School.

Stephen TURBAN: My name is Stephen Turban. I am a recent graduate of Harvard College and I currently work for a global management consultancy.

Turban has since moved on from his consulting job. Anyway, he and Bernstein had just co-authored a paper called “The Impact of the Open Workspace on Human Collaboration.”

TURBAN: I don’t think I realized how much anger there was against open offices until the research was published and I was contacted by a number of friends and colleagues about their open offices and their deep, deep emotional scarring.

BERNSTEIN: There’s certainly a population of people out there who hate — I think that’s perhaps even not strong enough—

DUBNER: Not strong enough, agreed. But proceed please.

BERNSTEIN: People find it impossible to get work done. They find it demoralizing.

TURBAN: Also the lack of privacy, and the feeling that they’re being watched by others.

BERNSTEIN: Privacy tends to give us license to be more experimental, to potentially find opportunities for continuous improvement, to avoid distractions that might take us away from the focus we have on our work.

TURBAN: Ethan is really, I would say, the king of privacy.

BERNSTEIN: My research over time has been about the increasingly transparent workplace and its impact on human behavior and therefore performance. Over time, I’ve gotten asked the question, “What about the open office? How does it impact the way in which people work and collaborate?” I haven’t had an empirical answer.

In search of an empirical answer, Bernstein and Turban began a study of two Fortune 500 companies that were converting from cubicles to open offices. Sure, the downsides of an open office are obvious: the lack of privacy; having to overhear everything your coworkers say. But what if the downsides are offset by a grand flowering of collaboration and communication and idea-generation? What if the open office is in fact a brilliant concept that we’ve all been falsely maligning?

* * *

The office is such a quintessential emblem of modern society that it may seem it’s been around forever. But of course it hasn’t.

Nikil SAVAL: The economy of the United States was based on farming and it was based on manufacturing. The office was almost an afterthought.

That’s Nikil Saval, the author of a book called Cubed: A Secret History of the Workplace.

SAVAL: People thought, “Well, offices are essentially paperwork factories. So we should just sort of array them in an assembly-line sort of formation.”

This meant a big room filled with long rows of desks and, scattered on the periphery, private offices for the managers. This factory model, which got its start in the late 19th century, came to be known as the American plan. And it was standard office form for decades, at least in the U.S. But then, in the middle of the twentieth century, in Germany:

SAVAL: There were two brothers, the Schnelle brothers, who began to wonder about the nature of the American plan. There was a sense that this was arbitrary, and there was no real reason to lay out an office in this way.

In 1958, Wolfgang and Eberhard Schnelle created the Quickborner consulting group with the idea of bringing some intentionality to modern office design.

SAVAL: And one of the ideas that came to them was that an office is not like a factory, it’s actually a different kind of workplace. And it requires its own sort of system. Maybe there isn’t a reason to have desks in rows. Maybe there isn’t a reason for people to have private offices at all, if essentially the office is not about producing things but it’s about producing ideas and about producing communication among different people. And so over time they pioneered a concept that they called the burolandschaft, or “office landscape.” And it was essentially the first truly open plan office.

The idea was to create an office that was more collaborative and more egalitarian.

SAVAL: It looks extremely chaotic. You’d just have desks in clusters and they just seem to be arranged in a pretty haphazard form. But, in fact, there was rigorous planning around it in a way that would facilitate communication and the flow of people and ideas. And it eventually made its way to England and the United States, and it was considered an incredible breakthrough.

A breakthrough perhaps — but the earliest open offices drew complaints similar to the ones we hear today. Lots of complaints.

SAVAL: By not instituting a barrier between people, by not having doors, by not having any way of controlling the way sound traveled in the office, it stopped facilitating the thing it was supposed to facilitate, which was communication, because it became harder to communicate in an office environment where phones were ringing off the hook, where you could hear typewriters across the room, and things like that. It wasn’t actually the utopian space that it promised to be. In fact, it was deeply debilitating in some ways for the kind of work that people wanted to do.

Meanwhile, there was an American named Robert Propst working for the Herman Miller furniture company, in Michigan.

SAVAL: He was not himself trained as a designer. He was sort of like a freelance thinker.

Propst was intrigued by the “office landscape” idea — its openness and egalitarian aspirations — but he also appreciated its practical shortcomings.

SAVAL: And he decided to turn to experts — to anthropologists, to social psychologists, to people of that nature.

After some research, Propst came to the conclusion that individuals are — well, they’re individuals. And they need more control over their workspace. He and the designer George Nelson came up with a new design in which each office worker would be surrounded by a suite of objects to help them work better. In 1964, Herman Miller debuted the “Action Office.”

SAVAL: There was a standing desk, a regular desk that you sat at, and a telephone booth.

Design critics loved the Action Office.

SAVAL: It looked incredible, but it was very expensive and very few managers wanted to spend this kind of money on their employees. So they went back to the drawing board and they tried to come up with something cheaper.

In 1968, Herman Miller released the Action Office 2.

SAVAL: And it was this three-walled space: these fabric-wrapped walls that were angled, and they were meant to enclose a suite of furniture. And it was meant to mitigate the kind of chaos that an open office plan might otherwise have.

You may know the Action Office 2 by its more generic name—

SAVAL: —which is the cubicle.

The cubicle promised a variety of advantages.

SAVAL: It’s meant to be very flexible, and it can form an impromptu conference room. And it was meant to divide up an open office plan in a way to mitigate the kind of chaos that an open office plan or an office landscape might otherwise have. And it was incredibly well-received. It was copied by a number of furniture companies. And soon it was spreading in offices everywhere.

But the cubicle could also be exploited.

SAVAL: It became a perfect tool for cramming more and more workers into less and less space very cheaply. The whole notion of what Propst was trying to do was to give a worker a space that they could control — was turned into the exact opposite. It was clear that his concept had become the most-loathed symbol of office life.

Indeed, the revolutionary, freedom-giving cubicle came to be seen as a sort of corporate version of solitary confinement. This left Robert Propst most unhappy.

SAVAL: And he blamed managers. He blamed people who were not enlightened, that created what he called barren, rat-hole-type environments.

Robert Propst, like the Schnelle brothers before him, had not quite succeeded in creating a vibrant and efficient open office. Their new environments introduced new problems: chaos in the first case, cubicles in the second. As with many problems that we humans try to correct — whether in office culture, or society at large — the correction turns out to be an overcorrection. Unintended consequences leap out, and humble us. And yet: in this case, the fact is that most offices today are still open offices. Why are we holding on to this concept if it makes so many people so unhappy?

TURBAN: If you’re looking purely at a cost per square foot, having an open office is cheaper.

BERNSTEIN: There are a lot of people, whether they’re managers or employees, who like the open office.

Bernstein admits that managers are primarily impressed by the cost savings of an open office. But some employees—

BERNSTEIN: Some employees like it because they have visions of it being more vibrant, more interactive. That fun, noisy, experiential place they’re hoping for once you take down the walls and make everyone able to see each other.

TURBAN: And there’s also been a big push around these collisions that have emerged in social sciences. How do you create these random interactions between people that spark creativity?

“Collision” is a term you hear a lot in office design and the design of public spaces generally. It’s the promise that unplanned encounters can lead to good things — between co-workers or neighbors, even strangers. Conversations that otherwise wouldn’t have happened; the exchange of ideas; unforeseen collaboration. Now, the office is plainly a different sort of space from the public square. The office is primarily concerned with productivity. We’d all like to be happy working in our offices, but is it maybe worth surrendering a bit of happiness — and privacy, and so on — for the sake of higher productivity? After all, that’s what we’re being paid for.

BERNSTEIN: If you want to have a certain kind of interaction that’s deep, productive in idea generation, or in something that requires us to have lots of “bandwidth” between each other, it’s nice to have that face-to-face interaction.

Ben WABER: Face-to-face conversations are so important.

That’s Ben Waber, he’s the C.E.O. of an organizational-analytics company called Humanyze.

WABER: What we do is use data about how people interact and collaborate at work. Think email, chat, meeting data, but now also sensor data about how people interact in the real world. And we use that to understand really what goes on inside companies.

Humanyze has developed sociometric I.D. badges, embedded with sensors, to capture these data.

WABER: We have by far the largest data set on workplace interaction in the world.

And what do the data say about face-to-face communication?

WABER: In all of our research, that has consistently been the most predictive factor of almost any organizational outcome you can think of: performance, job satisfaction, retention, you name it. People did evolve for millions of years to interact in a face-to-face way. We are very used to small changes in facial expression, small changes in tone of voice and that’s particularly important in work contexts where high levels of trust, especially as work gets more and more complex, and the things we build and make together are more and more complex. Really having that trust and being able to convey really rich information is critical.

Bernstein and Turban also believe in the value of face-to-face communication.

TURBAN: Nuanced communication around, “Here’s a proposal I have. Here is a thought I have about how this last meeting went.” That is a very rich and nuanced form of communication and most literature suggests that face-to-face communication is much better at that.

BERNSTEIN: Sociologists have suggested for a long time that propinquity breeds interaction — propinquity being co-location, being close to one another.

TURBAN: The closer two people are together, the more likely they are to interact, the more likely they are to get married, the more likely they are to work together.

BERNSTEIN: And interaction being, we will have a conversation, we will actually get some kind of collaboration done between the two of us.

TURBAN: You can look at slouching shoulders, you can see what is their facial expression, and that conveys a lot of information that is really hard to convey, no matter how good you are at emojis — and let me tell you, I am pretty good at emojis.

Okay, so face-to-face communication is important, at least for some purposes and on some dimensions. And an open office is designed to facilitate more face-to-face communication. So … does it work? That was the central question of Bernstein and Turban’s study.

DUBNER: In your study, there are two companies that were transitioning to open offices. First of all, can you reveal the identity of one or both of those companies?

BERNSTEIN: I can’t. In order to do this study, we had to agree to a level of confidentiality. I will say that we had a choice of sites to study and we chose the two that we thought would be most representative of the kind of work we were interested in, which is white-collar work in professional settings, Fortune 500 companies.

DUBNER: Can you give us some detail that helps us envision the kind of office and what the activities are?

BERNSTEIN: If you work in a global headquarters amongst a series of functions like H.R. or finance or legal or sales or marketing, this would describe your work setting.

DUBNER: And can you describe, for the two companies that you studied, they moved to open offices — what was their configuration beforehand?

BERNSTEIN: Everyone was in cubicles. And then they moved to an open space that basically mimicked that, but just without the cubicle walls.

TURBAN: Those barriers went down, so you could see if John was sitting next to Sally before, and there was a wall between them, that John could see Sally and Sally could see John, and that was the big difference between the original and the office afterwards.

DUBNER: So, tell us about the experiment. I want to know all kinds of things, like how many people were involved? Did they opt in or not? Was it randomized? How the data were gathered, and so on.

TURBAN: In the first study, we had 52 participants; in our second, we had 100 participants, and we wanted to measure communication before and after the move.

BERNSTEIN: We started with the most simple empirical puzzle we could start with, which was simply how much interaction takes place between the individuals before and after. We wanted to purely see if this hypothesis of a vibrant open office were true.

TURBAN: So before the move, we gave each of the participants sociometric badges.

These are the badges we mentioned earlier, from Humanyze.

BERNSTEIN: So they contain several sensors. One is a microphone. One is an I.R. sensor to show whether or not they’re facing another badge. They have an accelerometer to show movement and they have a Bluetooth sensor to show location.

TURBAN: So you can get a data point which looks like: “John spoke with Sally for 25 minutes at 2 p.m.” But you don’t know anything about what the content of the conversation is.

BERNSTEIN: A number of previous studies that have used the sociometric badges have shown that we are very aware of them for the first, say, few minutes that we have them on, and after that we sort of forget they’re there.

DUBNER: You write that the microphone is only registering that people talk and not recording or monitoring what they say. Do you think the employees who wore them believe that? I mean if I think there’s a one percent chance that my firm is monitoring or recording what I’m saying, I’m quite likely to say less, yes?

BERNSTEIN: Well, it’s actually kind of a funny question, because in this case we really weren’t. But look, we phrased the consent form as strongly as we could to ensure that they understood this was for research purposes, and if they hadn’t believed it, they probably would have opted out.

DUBNER: What are we to make of the fact that the data represents the people who opted in only? Because I’m just running through my head, if I were an employee and I’m told that there’s some kind of experiment going on with these smart people from Harvard Business School and, however much you tell me or don’t, I intuit some or I figure out some or I guess some. And we’re moving to an open office and I think, “Oh, man, I hate the open office, and therefore I definitely want to participate in this experiment so that I can sabotage it by behaving exactly the opposite of how I think they want me to behave.” Is that too skeptical or cynical?

BERNSTEIN: Boy, you sound like one of my reviewers in the peer review process.

DUBNER: Sorry.

BERNSTEIN: It is a valid concern. Let me tell you what we’ve tried to do to alleviate it. The first thing is we’ve compared the individuals who opted in to wearing the badge and those who did not to a series of demographics we got from the H.R. systems. And we don’t see systematic differences there.

TURBAN: It is always possible when you’re doing social science research that someone makes a guess, whether it’s accurate or not, about what this study is trying to understand, and then takes a personal stand and says, “I’m going to stand for what’s right, and what’s right is cubicles!” In that case, they would have to have done that for every day for two months. So it would have been a remarkable feat of endurance. We don’t think that that’s what happened, but the open office factions are real, so, definitely important to keep in mind.

In addition to all these data from the employees’ badges, the researchers could also measure each employee’s electronic communications — their emails and instant messages. Again, they were only measuring this communication, not examining the content.

BERNSTEIN: And so what we were able to do is compare individuals’ face-to-face and electronic communication before and after the move from cubicles to open spaces in these two environments.

Okay, so the Bernstein-Turban study looked at two Fortune 500 companies where employees had moved from cubicles to open offices. And they measured every input they could about how the employees’ communication changed — face-to-face and electronic communication. What do you think happened?

* * *

DUBNER: So, you’ve done the study, two firms over a period of time with a number of people to measure how their behavior changes, generally. Tell us what you found.

TURBAN: So, the study had two main conclusions.

BERNSTEIN: We found that when these individuals moved from closed cubicles into the open office, interaction decreased.

TURBAN: Face-to-face communication decreased by about 70 percent in both of our two studies. Conversely, that communication wasn’t entirely lost. Instead, the second result that we found was that communication actually increased virtually, so people emailed more, I.M.’ed more.

DUBNER: How much of that decrease was compensated by electronic?

TURBAN: We saw an increase of 20–50 percent of electronic communication. That means more emails, more I.M.’s. And depending on how you think about what an email is worth, maybe you could say that they made up for it. Is an email worth five minutes of conversation, is it two minutes?

BERNSTEIN: It’s a little bit hard to say, because an email and an interaction may not be comparable in item.

TURBAN: Even if we saw an increase in the amount of virtual communication, which totally made up for the face-to-face communication, what you probably saw was a loss in richness of communication — the net information that’s being conveyed was actually less.

DUBNER: What can you tell us about how the open space affected productivity and satisfaction?

BERNSTEIN: I’ll come out clean and say, we don’t have perfect data on performance, and we don’t have any data on satisfaction. We purposefully stayed away from satisfaction; we just wanted to look at the interaction of individuals. In one of our two studies, we have anecdotally some information where the organization felt that actually performance had declined as a result of this move.

I will say that, boy, if we think about this, there are probably lots of contexts that we can think of where more face-to-face interaction would be useful and lots of contexts in which we think more face-to-face interaction would not be useful. And that’s where I’d actually prefer to take the conversation about productivity. That, at the very least, to date managers of property, managers of organizations have not thought about this being a trade off. They’ve assumed cost and revenue go together. That may be true in some subset of environments, but in others that’s not going to be true.

DUBNER: What did the companies in your study do after you’d presented them with your findings?

BERNSTEIN: One of them has actually taken a step back from the open office. The other has attempted to make the open office work by adding more closed spaces to it.

Okay, so an empirical study of open offices finds that the primary benefit they are meant to confer — more face-to-face communication and the good things such communication can lead to — that it actually moves in the opposite direction! At least in the aggregate. To be fair, an open office is bound to be much better for certain tasks than others. And, more important, better for some people than for others. We’re not all the same. And some of us, I’m told — not me, but some of us — thrive in a potentially chattier office. But on balance, it would appear that being put out in the open leads most people to close themselves off a bit. Why? You can probably answer that question for yourself. But Turban and Bernstein have some thoughts too. Here’s one: maybe you don’t want to disturb other people:

TURBAN: So, when you’re in an open office, your voice carries. And I think people decide very reasonably to say, “Well I could speak with Tammy, who’s three desks away. But if I talk to Tammy, I’m going to disrupt Larry and Katherine, and so I will send her a quick message instead.”

Or maybe you compensate for the openness of the open office with behavior that sends a do-not-disturb signal.

BERNSTEIN: If everyone can see you, you want to signal to everyone that you are a hard worker, so you look intensely at your screen. Maybe you put on headphones to block the noise. Guess what? When we signal that, we also tend to signal, “And please don’t interrupt me from my work.” Which may very well have been part of what happened in our studies here.

And then there’s what Ethan Bernstein calls “the transparency paradox.”

BERNSTEIN: Very simply, the transparency paradox is the idea that increasingly transparent, open, observable workplaces can create less transparent employees.

For instance: let’s say you’ve been really productive all morning; now you want to take a break. You want to check your fantasy-football lineup; you want to look up some recipes for dinner. But you don’t want everyone in the office, especially your boss, to see what you’re doing. So: you do it anyway but you’re constantly looking over your shoulder in case you need to shut down the fantasy-football or recipe tabs.

BERNSTEIN: That has implications for productivity, because we spend time on it. We spend energy on it. We spend effort on it. We tend to believe these days that we get our best work done when we can be our authentic selves. Very few of us get up on a stage in front of a large audience, which is somewhat of how some people encounter the open office, and feel we can be our authentic selves.

Nicholas BLOOM: So, if I have an idea—

That’s the Stanford economist Nicholas Bloom.

BLOOM: —if I go discuss with my colleague or my manager in an open office, I’m terrified that other people would hear. They may pass judgment or rumors can go around.

Bloom has studied this realm for years:

BLOOM: I work a lot on firms and productivity, so what makes some firms more productive, more successful. What makes other firms less successful.

DUBNER: So let me ask you this: a recent paper found that a couple of Fortune 500 companies who switched from cubicles to an open office plan with the hopes of increasing employee collaboration, that in fact the openness led to less collaboration. So, knowing what you know about offices and people, does that surprise you?

BLOOM: Not really. There’s a huge problem with open offices in terms of collaboration. You have no privacy. Whereas if it’s in a slightly more closed environment it’s easier to discuss ideas, to bounce things around.

Or consider the ultimate closed environment: your own home.

BLOOM: One piece of research I did that connected very much to the open office was the benefits of working from home. So working from home has a terrible reputation amongst many people. The nickname “shirking from home.” So I decided to do a scientific study. So we got a large online travel agency to ask a division who wanted to work from home. And we then had them randomize employees by even or odd birthdays into working at home versus working in the office.

DUBNER: Now, this was a travel agency in China, correct?

BLOOM: Yes, so it’s Ctrip, which is China’s largest travel agency. It’s very much like Expedia in the U.S. And stunningly what came out was, one of the biggest driving factors is, it’s just much quieter working from home. They complained so often about the amount of noise and disruption going on in the office. They’re all in an open office and they tell us about people having boyfriend problems, there’s a cake in the breakout room. The World Cup sweepstake. I mean, the most amazing was the woman that told us about her cubicle neighbor who’d have endless conversations with her mum about medical problems, including horrible things like ingrown toenails and some kind of wart issue. I mean what could be more distracting than that? Not surprisingly, in that case, the open office was devastating for her productivity.

DUBNER: So, you find that overall, working from home raises what exactly? Is it productivity? Is it happiness?

BLOOM: So we found working from home raises productivity by 13 percent. Which is massive. That’s almost an extra day a week. So a), much more productive, massively more productive, way more than anyone predicted. And b), they seemed a lot happier; their attrition rates, so how frequently they quit. Part of this was they didn’t have the commute and all the uncertainty. And they didn’t have to take sick days off. But the other big driver is it’s just so much quieter at home.

DUBNER: You also do write, though, that one of the downsides of working from home was promotion became less likely. Yes?

BLOOM: Yes. We don’t know why, but one argument is “out of sight, out of mind.” They just get forgotten about. And another story would be that actually they need to develop skills of human capital and relationship capital, therefore you need to be in the office to get that, to be promoted. And then the third reason I heard, we talked to people working at home and they’d say, “I don’t want to be promoted, because in order to be promoted, I need to come in the office more so.” I’m happy where I am. It’s not worth it.

DUBNER: “I just want them to leave me alone.”

BLOOM: I mean, the most surprising thing from the Ctrip working-from-home experiment was after the end of the nine months, Ctrip was so happy. They were saving about $2,000 per employee working from home because they are more productive and they saved in office space. So they said, “Okay, everyone can now work from home.” And we discovered of the people in the experiment, about 50 percent of them who had been at home decided to come back into the office. And that seemed like an amazing decision because they’re now choosing to commute for something like 40 minutes each way a day. And also since they are less productive in the office and about half their pay was bonus pay, they’re getting paid less. All in all we calculated, their time and pay was kind of falling by 10 to 15 percent. But they were still coming in. And the reason they told us is it was lonely at home.

So people always joke the three great enemies of working from home is the fridge, the bed, and the television. And some people can handle that and others can’t. And you don’t really know until you have tried it. So what happens is people try it and some people love it and are very productive. Great, they just stick with it, and others try and they loathe it and they come back into the office.

The more you learn about the productivity and happiness of office workers in different settings, the more obvious it is that one key ingredient is often overlooked: choice. Some employees really might be better off at home; others might prefer the cubicle; and some might thrive in an open office. You also have to acknowledge that no one environment will be ideal for every task.

Janet POGUE McLAURIN: So if you stop and think about: how do we spend our time? About half of our time is spent in focus mode, which means that we’re working alone; a little over a quarter of our time is working with others in person; and about 20 percent is working with others virtually.

That’s Janet Pogue McLaurin, from the global design-and-architecture firm Gensler.

POGUE McLAURIN: I’m one of our global workplace practice area leaders.

Given the diversity of tasks required of the modern office worker—

POGUE McLAURIN: —you need the best environment for the task at hand. So, if you’re getting ready to go onto a conference call, instead of taking it at your desk, you may go into a conference room. When you finish that, you may go back to your desk to catch up on email. You may socialize around the café area or even take a walking meeting outside. We need to have all these other work settings at our disposal to be able to create a wonderful work experience.

That doesn’t sound so hard, does it? So how do you create that? Let’s start with the basics. Pogue McLaurin acknowledges that many open offices don’t address their key shortcoming.

POGUE McLAURIN: The biggest complaint that we see in open offices that don’t work is the noise. And how do you mitigate noise interruptions and distractions? And that can be noise as well as visual. Being able to design a space that zones the floor in smaller neighborhoods, that tries to get buffers between noisy activities. There’s architectural interventions we can also do, with ceilings and materials and white noise, that may be added to the space. And it’s not about creating too quiet an environment — that can be just as ineffective as a noisy environment. You really want to have enough buzz and energy, but just not hear every word.

You also want to account for what economists call heterogeneous preferences, and what normal people call individual choice.

POGUE McLAURIN: Choice is one of the key drivers of effective workspace, and we have found that the most innovative firms actually offer twice as much choice and exercise on that choice than non-innovative firms do. And choice is really around autonomy, about when and where to work. It could be as simple as having a choice of being able to do focus work in the morning or being able to work at home a day, or in another work setting in the office.

To that end, no two employees are exactly alike — and, more important, no two companies are alike either.

POGUE McLAURIN: I think some common mistakes that organizations do is they try to copy someone else’s design. So if you think it’s a cool idea of something that you saw on the west coast, let’s say it’s a tech firm, and you’re not even a tech firm, and you’re sitting here on the east coast and you try to just copy it verbatim, it doesn’t work. It’s got to reflect how your organization works and the purpose and brand and community that you’re a part of.

So oftentimes, companies would start to adopt what other organizations are doing and say, “Yes, that will save us space, so let’s adopt it,” but they’re missing out by not providing all these other spaces to balance. So they want the efficiency without creating all the other work settings that people need in order to be truly productive.

It’s worth noting that Janet Pogue McLaurin, a principal with a design-and-architecture firm, is arguing that the key to a successful office is: design and architecture. But it’s also worth noting that her firm has done a great deal of research in all different kinds of offices, all different kinds of companies, all over the world.

POGUE McLAURIN: We’ve done several studies in the U.S. and the U.K. But we’ve also done Latin America, Asia, Middle East and we’re just completing a study in Germany.

So: what’s her prognosis for the long-maligned open office?

POGUE McLAURIN: The open office is not dead. Oftentimes people say,“Which is better: private office or open plan?” We measured all types of individual work environments, and what we’ve found is that if you solve for design, noise, and access to people and resources, they perform equally, and one is essentially not better than the other. And the best open plan can be as effective as a private one. And that was a surprise. I love data when it tells you something unexpected.

So do we, Janet Pogue McLaurin. So do we.

* * *

Freakonomics Radio is produced by Stitcher and Dubner Productions. This episode was produced by Rebecca Lee Douglas. Our staff also includes Alison Craiglow, Greg Rippin, Harry Huggins, Zack Lapinski, Matt Hickey, Corinne Wallace, and Daphne Chen. We had help this week from Nellie Osborne. Our theme song is “Mr. Fortune,” by the Hitchhikers; all the other music was composed by Luis Guerra. You can subscribe to Freakonomics Radio on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Here’s where you can learn more about the people and ideas in this episode:

SOURCES

Ethan Bernstein, Edward W. Conard Associate Professor of Business Administration at the Harvard Business School.

Nicholas Bloom, economist at Stanford University.

Janet Pogue McLaurin, principal at Gensler.

Nikil Saval, author and journalist.

Stephen Turban, development & innovation at the Office of the President, Fulbright University Vietnam.

Ben Waber, president and C.E.O. of Humanyze.

RESOURCES

“Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment,” Nicholas Bloom, James Liang, John Roberts, Zhichun Jenny Ying (2013).

“The Impact of the Open Workspace on Human Collaboration,” Ethan Bernstein, Stephen Turban (2018).

The Office: A Facility Based on Change by Robert Propst (Herman Miller 1968).

Cubed: A Secret History of the Workplace by Nikil Saval (Anchor 2014).

EXTRA

“Are We in a Mattress-Store Bubble?” Freakonomics Radio (2016).

“Time to Take Back the Toilet,” Freakonomics Radio (2014).

The post Yes, the Open Office Is Terrible — But It Doesn’t Have to Be (Ep. 358 Rebroadcast) appeared first on Freakonomics.

from Dental Care Tips http://freakonomics.com/podcast/office-rebroadcast/

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Roland T. Owen, and the horror in room 1046

In Kansas City, Missouri, on the afternoon of January 2, 1935, a man walked into the Hotel President and asked for a room several floors up. He carried no luggage. He signed the register as “Roland T. Owen,” of Los Angeles, and paid for one day’s stay. He was described as a tall, “husky” young man with a cauliflower ear and a large scar on the side of his head. He was given room 1046.

On the way to his room, Owen told the bellboy, Randolph Propst, that he had originally thought to check into the Muehlebach Hotel, but was put off by the high price of $5 a night. When they reached 1046, Owen took a comb, brush, and toothpaste out of his coat pocket and placed them in the bathroom. Then, the pair went back out in the hall, where the bellboy locked the door. He gave Owen the key, after which the new guest left the hotel and the bellboy returned to his usual duties.

Later that day, a maid went to clean 1046. Owen was inside the room. He allowed her in, telling her to leave the door unlocked, as he was shortly expecting a friend. She noticed that the shades were tightly drawn, with only one small lamp to provide illumination. She later told police that Owen seemed nervous, even afraid. While she cleaned up, Owen put on his coat and left, reminding the maid not to lock the door.

Around 4 p.m., the maid returned to 1046 with fresh towels. The door was still unlocked, and the room still eerily dim. Owen was lying on the bed, fully dressed. She saw a note on the desk that read, “Don, I will be back in fifteen minutes. Wait.”

The next we know of Owen’s movements came at about 10:30 the next morning, when the maid came to clean his room. She unlocked the door with a passkey (something she could only do if the door had been locked from the outside.) When she entered, she was a bit unnerved to see Owen sitting silently in a chair, staring into the darkness. This awkward moment was broken by the ringing of the phone. Owen answered it. After listening for a moment, he said, “No, Don, I don’t want to eat. I am not hungry. I just had breakfast.” After he hung up, for some reason he began interrogating the maid about the President Hotel and her duties there. He repeated his complaint about the high rates of the Muehlebach.

The maid finished tidying the room, took the used towels, and left, no doubt happy to leave this strange guest.

That afternoon, she again went to 1046 with clean towels. Outside the door, she heard two men talking. She knocked, and explained why she was there. An unfamiliar voice responded gruffly that they didn’t need any towels. The maid shrugged to herself and left.

Later that day, a Jean Owen (no relation to Roland) registered at the President, and was given room 1048. She did not have a peaceful night. She was continually bothered by the loud sounds of at least male and female voices arguing violently in the adjoining room. Mrs. Owen later heard a scuffle and a “gasping sound” which at the time she assumed was snoring. She debated calling the desk clerk, but unfortunately decided against it.

Charles Blocher, the graveyard shift elevator operator at the hotel, also noticed unusual activity that night. There was what he assumed was a particularly noisy party in room 1055. Some time after midnight, he took a woman to the 10th floor. She was looking for room 1026. He had seen her around the President numerous times–she was, as he put it discreetly, “a woman who frequents the hotel with different men in different rooms.”

A few minutes later, he was signaled to return to the 10th floor. The woman was concerned because the man who had arranged to meet her there was nowhere to be found. Being unable to help her, Blocher went back downstairs. About half an hour later, the woman summoned him again to take her down to the lobby. About an hour later, she returned to the elevator with a man. Blocher took them to the 9th floor. Around 4 a.m. the woman left the hotel, followed about fifteen minutes later by the man. This couple was never identified, and it is unknown what, if anything, they had to do with Owen and room 1046.

At about 11 p.m. that same night, a city worker named Robert Lane was driving on a downtown street when he saw a man running down the sidewalk. He was puzzled to see that on this winter night, the stranger was wearing only pants and an undershirt.

The man waved Lane down, thinking he was a taxi driver. When he saw his mistake, he apologized and asked if Lane could take him someplace where he could get a cab. Lane agreed, commenting, “You look as if you’ve been in it bad.” The man nodded and growled “I’ll kill that [expletive discreetly deleted in newspaper reports] tomorrow.” Lane noticed his passenger had a wound on his arm.

When they reached their destination, the man thanked Lane, then exited the car and hailed a cab. Lane drove off, having no idea that he had just played a minor role in one of his city’s weirdest murder mysteries.

Around 7 a.m. the next morning, the President’s telephone operator noticed that the phone in room 1046 was off the hook. After three hours had passed without anyone placing the phone in its cradle, she sent Randolph Propst to tell whoever was there to hang up. The bellboy found the door locked, with a “Don’t disturb” sign out. When he knocked, after a moment he heard a voice tell him to come in. When he tried the door, he found it was still locked. He knocked again, only to have the voice tell him to turn on the lights. After a couple more minutes of fruitless knocking, Propst finally yelled, “Put the phone back on the hook!” and left, shaking his head at what he assumed was their crazy drunken guest.

An hour and a half later, the operator saw the phone was still unhooked. She sent another bellboy, Harold Pike, up to deal with the problem. Pike found 1046 still locked. He used a passkey to open the door–showing that it had again been locked from the outside. In the dimness, he was able to make out that Owen was lying on the bed naked. The telephone stand had been knocked down, and the phone was on the ground. The bellboy put the stand upright and replaced the phone.

Like Propst, he assumed their guest was merely drunk. He left without bothering to check Owen’s condition more closely.

Shortly before 11 a.m., another telephone operator noticed that the phone in 1046 was again off the hook. Once again, Propst was sent up to the room. He found the “Don’t disturb” sign still on the door. After his knocks got no response, he opened the door with his passkey and walked inside.

The bellboy found something far worse than mere intoxication. Owen, still naked, was crouched on the floor, holding his bloody head in his hands. When Propst turned on the light, he saw more blood on the walls and in the bathroom. The frightened bellboy rushed out and told the assistant manager, who summoned police.