#salome c edit

Text

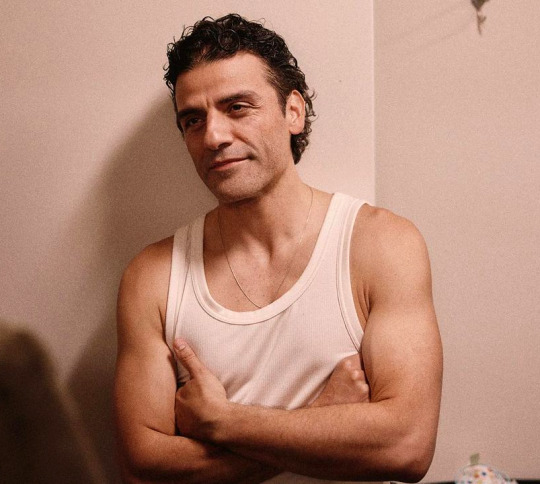

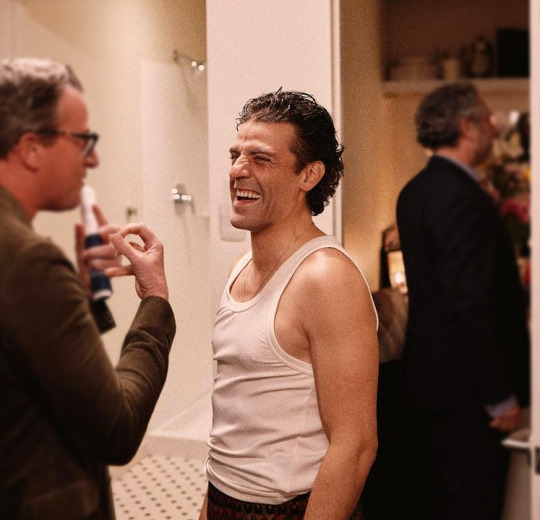

The Sign In Sidney Brustein's Window Opening Gala. (x)

#oscar isaac#oscarisaac#oisaac#oscarisaacedit#oscar isaac edit#the sign in sidney brustein's window#broadway#salome-c edit#salome c edit

612 notes

·

View notes

Text

salomé, salomé, dance for me.

#this edit is kinda mid but shes hot so it doesnt matter#anyway rip to vladdy sorry#ts4 edit#sims4#ts4#sims4 edit#vampire hunter#sims 4 vampires#sims 4 screenshots#c: pauline#goth#vladislaus straud#salome#spooky

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

i am once again begging for a head canon/imagine based on a gif of matty: car sex/steamy interaction edition

mwah 💕🪷 take your time and if you celebrated any of the holy week holidays i hope it was pleasant 💕🤍🪷

Stress Relief

Matt Murdock x gn!Reader (No Y/N)

Rating: M- this is 18+ so minors better get off my lawn

Warnings: smutty vibes

Word count: a bit over 400

Author’s note: thanks for this ask and sorry it took me so long to answer it!

P.S. Here’s a link to my masterlist if you’d like to check out my other writing!

You rolled the window down and called Matt’s name as soon as you saw him walk out the door and onto the sidewalk.

He grinned as he opened the passenger door and sat himself in your car.

“Hey sweetheart,” he said, voice syrupy sweet, as he pressed a soft kiss to your lips.

“Hey,” you said distractedly as you pulled back into traffic and tapped your fingers anxiously.

His fingers grazed up your arm as he asked, “You okay?”

“Yeah, yeah, for sure,” you muttered back unconvincingly as you honked your horn at the car in front of you for going too slow.

“Damn it,” you grumbled.

He grabbed your hand and squeezed it three times and then pressed a kiss to your palm.

“You seem stressed,” he murmured as he pressed a kiss to the inside of your wrist.

Your breath hitched and you glanced over at him.

His lips moved slowly from your wrist up the inside of your arm.

“Matt-“

“What’s wrong?”

You sighed. “I’m stressed.”

“Obviously,” he said with another press of his lips to your skin, “you didn’t even call me pretty boy.”

You choked out a laugh. “Aw, I’m sorry, pretty boy. I just don’t really want to go to this stupid wedding and I don’t want to be late and I’m all worked up about it.”

His lips had reached your shoulder now and he bit down before he asked, “So why are we going?”

“Because if I don’t go then it’ll cause drama and will be a whole thing,” you huffed.

He continued his trail of kisses up to your neck and you smiled.

“And I’m dragging you along with me to make it less miserable for me.”

“Maybe I could make it actually enjoyable for you,” he said and you gasped as his teeth pressed into your pulse point.

“Pull over,” he whispered.

“But we’ll be late,” you gasped out as his fingers drifted across your chest.

“C’mon let me relieve some of that stress,” he murmured as he kissed your neck again.

“Shit, fuck, damn it,” you muttered as you found a safe and secluded place to pull the car over.

As soon as you yanked the car into park you unbuckled your seatbelt and lunged for him.

You slammed your lips into his and he chuckled into your mouth as he pulled you the rest of the way onto his lap.

Needless to say, you were late for the wedding, but it was totally worth it.

Matt Murdock Taglist:

@mindidjarin @hotnmad @samwisethegr8 @catholicdaredevil @salome-c @sobachka-korol @carters-things @enjoymyloves

Everything taglist:

@spideysimpossiblegirl @dinandgone @ohpedromypedro @littlemisspascal @tombraider42017 @kirsteng42 @just-here-for-the-moment

#matt murdock#daredevil#matt murdock x reader#matt murdock x y/n#matt murdock x you#daredevil x reader#daredevil x you#daredevil x y/n#matt murdock smut

203 notes

·

View notes

Photo

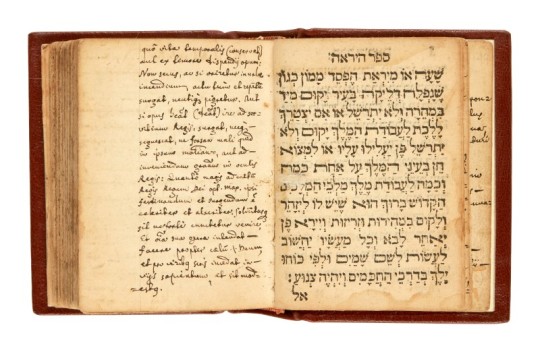

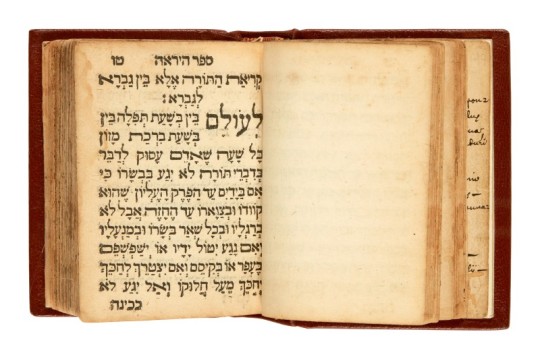

Sefer hayirah, traditionally attributed to Rabbi Jonah Gerondi, edited by Salom ben Joseph Gallego. Amsterdam: Menasseh ben Israel, 1627, 87 x 60mm

An early pocket-sized publication from the press of Menasseh ben Israel, where Gallego worked as corrector and editor. Jonah Gerondi was a thirteenth century Catalan rabbi whose work on ethics, discussing the behaviour appropriate for a God-fearing man, first appeared in print in c. 1492-1496. It is now thought that the attribution to Gerondi may be spurious.

The partial translation into Latin of this copy indicates that it was read by a non-Jewish scholar who was competent in Hebrew.

#jumblr#judaism#printed books#rabbi jonah gerondi#salom ben joseph gallego#menasseh ben israel#netherlands#myposts

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

broken mediator

a/n: @astroboots asked me to share a poem i’m proud of for my hc + request event -- here you go, my dear! xx [edit: i did not write this recently! i wrote this about five-six months ago.]

***

these days? ‘ when i think of you:

shards collapse on a spectrum of extremity

Not light nor dark nor this nor that, but non binary colorations of

sculpted remembrance

one singular instance morphs into a memento mori —

seconds splice into texts : thinking of thinking about you (prev.)

is the way i feel after i drink coffee when i shouldn’t

the heart does not understand referred pain

vita mutator, non tollitor, or so i am told

transience is a zipper of being and becoming

what is stillness, if not death?

sometimes the context of departure must be buried in the act itself

this phantasmagoric impression of past modes

lacks mean and median

Moderation has never been cemented.

you could not skew my soul so much as it was Pierced.

i still recall where you first attached your psyche to mine

but i cannot hear, you are no longer you (a bland imagination takes the place

where your words spilled out) (and who are you without your words)

that is who you have become to me ‘ a listless vision of intimate anonymity

the pain is mine and yet not so: so too with anger : even less of love

distance does not render me numb it pushes

— a microcosmic coexistence of vehemence and betrayal ,

but screaming expresses both of those quite nicely

i scream to expunge you from my blood because the sliding scale

cannot seem to tell me where the fault lines are (just where the earthquake is , a

plummeting chasm)

the mesh screen between now and then that covers the abyss of us permits

then to seep into now and now to crash into then, it’s just a flimsy wire grate held together by disbelief and triumph (dual dichotomies , be they falsely true or noble lies)

i feel no colors when i write about you adopting your colorless tone

does not mitigate my bipolarity

i am water and i need these aqueous solutions, these torrid pages to breathe even as bonds flex under the strain

i am me without you (and yet not so)

****

UPDATED taglist form!

tags for la poesie: @frannyzooey @nobie @dindja @catsnkooks @freeshavocadoooo @lilhawkeye3 @clan-djarin @princessxkenobi @keeper0fthestars @justrunamok @thewayofthemandalorian @anakinswhore @star-whores-a-new-hoe @softdin @darthadeline @cannedsoupsucks @forever-rogue @kat-r-in @rentskenobi @leonieb @javisjeanjacket @agirllovespancakes @phoenixhalliwell @mitchi-c @salome-c @a-skov @amneris21 @maciiiofficial @perropascal @goldafterglow @kyjoraven @/astroboots @ladytrashbird

#writing#my writing#poetry#writers on tumblr#cris writes#cici tag 🌾#queue yourself you’re pretty cute#this is best read on desktop!!#y'all were all like 'oh god the pain!'#hence the disclaimer i did not write this recently lmao#epilogue inspo

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thabj you for taggin me @fisforfulcrum <3

1. Why did you choose your URL?

Idk I wanted something with Pedro in it and... this happened

2. Any side blogs?

nope

3. How long have you been on tumblr?

I made my first blog in 2011 I think

4. Do you have a queue tag?

Nope. I'm too disorganized for that :D

5. Why did you start your blog in the first place?

This blog? Well, I fell in love with Pedro and after not being active on Tumblr for a year I was missing people to fangirl with.

6. Why did you choose your icon/pfp?

I couldn't decide which Pedro icon to use, so I decided to do something different.

7. Why did you choose your header?

because @sirtadcooper makes the most beautiful headers/icons/edits and I fell particularly hard for this one

8. What’s your post with the most notes?

I think me being angry we didn't get to see Oberyn with his daughters in GoT

9. How many mutuals do you have?

Oh wow Idk. A lot i'd say?

10. How many follows do you have?

Had to check and apparently, there's 235 of you???

11. How many people do you follow?

121

12. Have you ever made a shitpost?

ehhhh I think so

13. How often do you use tumblr each day?

Depends on what I'm doing, but I tend to pop in every few hours or so when working, out with someone etc.

14. Did you have a fight with another blog once?

God, my memory can't go back that far, but maybe once?

15. How do you feel about “you need to reblog this” posts?

I used to reblog every one of them when I was younger, but they do make me anxious, so I don't really do it anymore. I know they are important, but please, I just wanna look at pictures and read fanfics.

16. Do you like tag games?

YES! I love tag games

17. Which of your mutuals do you think is tumblr famous?

Uhmmmm I'm pretty sure @abelmorales @sirtadcooper @keanurevees and several of my mutuals who write fanfic

18. Do you have a crush on a mutual?

Obviously. You are all like the captain of the football team while I'm I the corner with my glasses and nerdy shit, picturing our wedding.

No pressure tags: @phantomviola @chasingdreamer @salome-c @pedropastelpascal @sirtadcooper @dindjarin-mandalorian @neptunesglow @fisforfulcrum

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

a r m s

#this is taking me to other places#just i cant#pedro pascal#pedropascal#ppascal#pedro pascal edit#pedropascaledit#pedro pascal character#salome-c edit#salome c edit

712 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bibliography

KEY ARTWORKS

Beardsley, A. (1891). Salome. [black ink].

Arrivebene, A. (2011). Martyrium S. Dorothea. Accessed at http://www.agostinoarrivabene.it/

Lorca, G. (2020). La Cama Inglesa. Available at: https://www.guillermolorca.com/.

Doré, G. (1872). fall of the rebel angels. [engraving].

Fairlie, A. (1984). Baudelaire : les fleurs du mal. London: E. Arnold.

Fuseli, H. (1781). the nightmare.

Giger, H. (2020). HR Giger - The Official Website. [online] Hrgiger.com. Available at: https://www.hrgiger.com/.

Roux, M. (1901) Mauvaise pensée obsédante

Anthromorph, 101 (2021), [digital portrait], 111 series, London [Online] Available at https://shop.playform.io/artshop?exhibitions=Unnatural%20Selections. (Accessed 10 February 2021)

BOOKS

Sigmund Freud (2015). Beyond the pleasure principle. Mineola, New York: Dover Publication, Inc.

Georges Bataille (2011). Death and sensuality : a study of eroticism and the taboo. Whitefish, Montana: Literary Licensing, Llc.

Ligotti, T. (2009). My work is not yet done : three tales of corporate horror. London: Virgin Books.

This Fiction book by Thomas Ligotti is a tale of corporate horror. I fell in love with his writing style, his description of dark and also nothingness had a big impact on me. There is a poem which is an epilogue to this book (I have a special plan for this world) which is also beautifully dark and thought provoking.

Jean-Paul Sartre (1938). La nausee. Paris: Gallimard.

This philosophical novel resonated with me strongly, the subtle but haunting feeling of nausea that follows him through the book stems from Sartre’s existential beliefs. I found these feelings described very fascinating and unique, and these thoughts stuck with my threw my process of art making. His writing is very beautiful and I am lucky enough to be able to read it in the original language.

Sigmund Freud (2015). Beyond the pleasure principle. Mineola, New York: Dover Publication, Inc.

Kentarō Miura, Deangelis, J., Johnson, D., Nakrosis, D. and Studio Cutie (2016). Berserk. Deluxe edition Volume 2. Milwaukie, Oregon: Dark Horse Manga.

Kentaro Miura’s manga style has been very inspiring for me. His strictly black and white illustrations are extremely impactful, dramatic and narrate his stories very strongly. Narration is important in my work even though I haven’t created a linear story. I feel that as a whole through repeated motifs, a story-like structure has been created and a unique narration can be noticed by each viewer.

Tsing, A. (2017). The mushroom at the end of the world: on the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton University Press, London. 288p

Anna Tsing’s book was on of my main research points for my MCP and I believe that her writing has been the most influential towards my ideas after this research. The story of the mushroom growing back from ruin really stuck with me and the idea of interconnectivity in nature, and the cycles of life and death are very important in my artwork.

ESSAYS

Ginzburg, C. (1983). The night battles. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press

The night battles was a very influential text to me, reading about the reality behind witchcraft was very eye opening, these are themes that have followed me through my work. I have always been interested in magic and spirituality so understanding the dark reality of such matters guided my creation of imagery related to this subject.

Haraway, D. (1984). A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology and Socialist-Feminism. University of Minnesota Press. [Online] Available at: https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/english/currentstudents/undergraduate/modules/fictionnownarrativemediaandtheoryinthe21stcentury/manifestly_haraway_----_a_cyborg_manifesto_science_technology_and_socialist-feminism_in_the_....pdf (Accessed 10 October 2020)

Bul, Lee. “Ursula K. Le Guin, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction.” The Carrier Bag Therory of Fiction, 1966, doi:https://www.deveron-projects.com/site_media/uploads/leguin.pdf.

FILMS

Suspiria. (1977). Produzioni Atlas Consorziate.

Suspira was a very special film in my research process. Since I trained as a ballet dancer for all of my childhood years this movie brought back a lot of feelings related to the horror behind such a beautiful art form. Dario Argento’s style and creativity is very breath-taking in this film and I feel that he represented a beautiful world through destruction and death very effectively.

The shape of water. (2017). TSG Entertainment.

Guillermo Del Toro was also a very influential director for me. I have watched many of his films through my childhood to now and his fictive characters and highly emotional movies have always stuck with me. This has guided a lot of my creativity when I have been drawing creatures and monsters in my own work. I love that he represents these mythical/extra-terrestrial characters from kind and loving to unsettling and dangerous.

Possession. (1981). Gaumont film company.

Abstract way of representing love and relationships.Reflects on the complicated nature of love and real relationships.

Noé, Gaspar, director. Enter the Void. Wild Bunch Distribution , 2009.

the cell. (2000). new line cinema.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

16 with gradence, 29 with my perfect eldritch girl

This is both of these things, I hope!!

Warnings for: nightmares, implied past abuse, weird eldritch stuff (not bad, just a little reality-bending darkness), Salome crying, this is very H/C. For those who feel lost, Salome is from this fic over here. I didn’t edit this.

~1,200 words.

—

The day had begun as any other — at a leisurely pace, with the New York Ghost spread across the kitchen table and the young Mrs. Graves sighing softly between sips of coffee. In between swallows, she may have stuck the infinite chocolate spoon in her mouth once or twice with an impish lift to the corners of her pink mouth.

By all accounts, it was a lovely morning.

Mrs. Graves stepped out on her own with a new, wool cape wrapped around her shoulders and the slightest hint of mint and chocolate on her breath. The only thing Mr. Graves had asked for before she left was one kiss; she was generous enough to give him three.

For Mr. Percival Graves, the day continued pleasantly. He answered letters and made the smallest bit of progress in charming a pocket watch to tell him when the person speaking to him was lying. Currently, it was too sensitive to be useful — so much as asking the waiter what specials they recommended for the night could set it off.

When he finally left his study, however, he found the young Mrs. Graves sitting in their parlor all in white. Her distress seemed to distort the air around her, making it heavy with darkness and magic. It bent the light into shadow and leaked out of her skin like smoke. Her expression was a perfect porcelain mask of her face.

“Darling?” he asked.

She looked at him and her eyes widened. She stood up suddenly, dragging all her darkness with her.

“Has something upset you?” he asked.

“No,” she answered.

“You’re wearing your wedding dress,” he said.

“Yes,” she said and her lower lip trembled as she spoke.

“I only point it out because you look absolutely stunning in it,” he told her, “as you do always.”

“Thank you,” she said.

She had the most impressive ability to cry without moving her face at all, as though she simply pretended that tears weren’t falling from her eyes. She sniffed slightly and the darkness rippled around her.

“I think I ought to go upstairs,” she said. “I don’t want to intrude on your work today and I’m.. I’m no use to anyone.”

She walked past him and every hair on his body seemed to stand up. He felt her darkness crawling over his skin beneath his clothing, a teasing brush of cold menace. He let her go.

Underneath the table beside the seat she had vacated, a half-finished list sat crumpled on the hardwood floor. Percival brought it to his hand with the simple flick of his wrist, though he had to find some flat surface upon which to smooth it flat again. It was mostly completed, items and tasks written in her tidy penmanship and then crossed out.

It was not that Percival Graves hated to go out of his house, it was that he absolutely loathed it. At least with his wife on his arm, there were four eyes and four ears — three hands between the two of them. He clenched his jaw and sighed.

On his way back from the last of the errands, with a cold sweat still upon his brow, he ducked into the doorway of a florist’s shop and walked out with a few stems of lilies wrapped in paper.

These went into a glass vase with some water while all the foodstuffs tucked themselves into the larder and icebox. Mr. Percival Graves noted that his wife had put everything else on the list away and then changed into her wedding dress all without his notice earlier that afternoon — despite her obvious despair.

He carefully carried the vase upstairs.

“Mrs. Graves?” he asked at the door to their bedroom.

When he received no answer, he opened the door by magic. The lights lifted by magic as well. All that could be seen of the young Mrs. Graves was a tight knot under the blankets. Percival set the lilies on the table beside her.

“Darling?” he asked.

“My beautiful wife?”

He knelt beside the bed and placed his hand where he hoped her shoulder might be.

“Salome?”

Slowly, the shape of her unfurled and slowly revealed itself like a flower in bloom. Her dark hair was badly mussed and her carefully applied makeup smudged to grey around her eyes.

“Hello, my love,” he said, as softly as he could.

“Percival,” she said. She looked at him for a moment and then turned her eyes away.

“Would you like to talk about what’s upsetting you?” he asked.

“No,” she said. “I would rather not.”

“Alright,” he said.

He had nightmares, constant and violent nightmares, which would shake him awake in the night with sobs caught in his strangled throat. He dreamed often that all of this, his life and his home and his bride, was all an illusion. He dreamed of sandbags holding back torrents of blood, clotted and dark as soil. He dreamed of much worse things. Sometimes, his dreams were only memories.

His wife would turn on all of the lights for him and check all of the locks in the house, even the wards. She would tell him in a calm and soft voice that he had been dreaming. She would listen to him tell her about these things, real and imagined and all horrible. She would draw a cool, wet cloth over his face or his neck or his hair. She would kiss him. She would touch him and fill his mouth with every sweet word she knew.

He owed all the peace in his life to her.

“May I have your hand?” he asked.

Her sharp expression asked why, but she reached out from beneath the bedding and offered her gloved hand. He tugged the fabric on her fingers loose first and then peeled it off. The knuckles were badly marked; the middle finger, crooked from an old broken bone; the palms, creased with scars that had turned black. Percival held it in his own, bare skin against bare skin. He kissed her wedding band first.

“Salome,” he said.

“I love you.”

He kissed it again. He kissed each knuckles. He traced her veins with his kisses, the bones and tendons of her. Each kiss he punctuated with his declaration, the sweetest words he knew.

“I love you. I love you. I love you.”

He kissed the black and now oozing lines on her palms. He kissed the callused tips of her fingers. He kissed her all the way to her wrist and then back down past that once broken bone to the whorl of her fingertip.

When he stopped, she moved her hand to his face. Her palm brushed against his cheek and her thumb rested upon the point of his upper lip.

“My wife,” he said.

“Yes,” she said. “Please, call me by name.”

“Salome,” he said, looking into her dark eyes. “I love you.”

She sighed, a chocolate spoon and coffee sigh.

“You brought me flowers,” she said.

“Lilies always remind me of our wedding day,” he told her.

“Percival,” she said.

She leaned toward him with the softest sound of fabric moving against fabric. Her lips were cool against his.

“I love you,” she breathed.

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

THE HOLY GOSPEL OF JESUS CHRIST, ACCORDING TO ST. John, FROM THE LATIN VULGATE BIBLE

Chapter 15

PREFACE.

St. John, the evangelist, a native of Bathsaida, in Galilee, was the son of Zebedee and Salome. He was by profession a fisherman. Our Lord gave to John, and to James, his brother, the surname of Boanerges, or, sons of thunder; most probably for their great zeal, and for their soliciting permission to call fire from heaven to destroy the city of the Samaritans, who refused to receive their Master. St. John is supposed to have been called to the apostleship younger than any of the other apostles, not being more than twenty-five or twenty-six years old. The Fathers teach that he never married. Our Lord had for him a particular regard, of which he gave the most marked proofs at the moment of his expiring on the cross, by intrusting to his care his virgin Mother. He is the only one of the apostles that did not leave his divine Master in his passion and death. In the reign of Domitian, he was conveyed to Rome, and thrown into a cauldron of boiling oil, from which he came out unhurt. He was afterwards banished to the island of Patmos, where he wrote his book of Revelations; In his gospel, St. John omits very many leading facts and circumstances mentioned by the other three evangelists, supposing his readers sufficiently instructed in points which his silence approved. It is universally agreed, that St. John had seen and approved of the other three gospels.

Chapter 15

A continuation of Christ's discourse to his disciples.

1 I am the true vine; and my Father is the husbandman.

Notes & Commentary:

Ver 1. I am the true vine. Christ, says St. Augustine, speaks of himself, as man, when he compares himself to a vine, his disciples to the branches, and his Father to the husbandman. He himself, as God, is also the husbandman. --- Without me, you can do nothing, that shall be meritorious of a reward in heaven. (Witham) --- These words are supposed to have been spoken by our Saviour, when on the road, as he was going from the house, where he had supped, to the garden of Olives. It was then about midnight. (Calmet) --- Though many other interpreters think they were spoken before Jesus Christ left the house.

2 Every branch in me, that beareth not fruit, he will take away: and every one that beareth fruit, he will purge it, that it may bring forth more fruit.

Ver. 2. He here shews, that the virtuous themselves stand in need of the help of the husbandman; therefore the Almighty sends them tribulations, and temptations, that they may be cleansed, and rendered firm, like the vine, which, the more it is pruned, the more vigorous are its shoots. (St. Chrysostom, hom. lxxv. in Joan.)

3 Now you are clean, by reason of the word, which I have spoken to you.

Ver. 3. See John xiii. 10.

4 Remain in me: and I in you. As the branch cannot bear fruit of itself, unless it abide in the vine: so neither can you, unless you abide in me.

Ver. 4. No explanation given.

5 I am the vine: you the branches: he that abideth in me, and I in him, the same beareth much fruit: for without me you can do nothing.

Ver. 5. No explanation given.

6 If any one remaineth not in me, he shall be cast forth as a branch, and shall wither, and they shall gather him up, and cast him into the fire, and he burneth.

Ver. 6. No explanation given.

7 If you remain in me, and my words remain in you: you shall ask whatever you will, and it shall be done to you.

Ver. 7. On account of our being in this world, we sometimes ask for that, which is not expedient for us. But these things will not be granted us, if we remain in Christ, who never grants us any thing, unless it be profitable to us. (St. Augustine, tract. 81. in Joan.) --- If we abide in Christ, by a lively faith, and his words abide in us by a lively, ardent charity, which can make us produce the fruits of good works, all that we ask, will be granted us. (Bible de Vence) --- These conditional expressions, if you remain in the vine, if you keep my commandments, &c. give us to understand, that our perseverance and salvation are upon conditions, to be fulfilled by us. --- (St. Augustine, de cor. & gra. chap. 13.)

8 In this is my Father glorified, that you bring forth very much fruit, and become my disciples.

Ver. 8. It is the glory of the husbandman, to see his vine well cultivated, and laden with fruit. And it is the glory of God, my Father, to see you filled with faith, charity, and good works, and to behold you usefully employed, in the conversion of others. Then will men, seeing your good works, and the fruit of your preaching, among all nations, glorify your heavenly Father, as the author of all these blessings. (St. Matthew v. 16.) (Calmet)

9 As the Father hath loved me, I also have loved you. Remain in my love.

Ver. 9. No explanation given.

10 If you keep my commandments, you will remain in my love, as I also have kept my Father's commandments, and do remain in his love.

Ver. 10. As I also have kept my Father's commandments. He still speaks of himself, as man. (Witham) --- This frequent admonition, of keeping the commandments, proveth, that a Christian's life consists not in faith only, but in good works. (Bristow)

11 These things I have spoken to you: that my joy may be in you, and your joy may be filled.

Ver. 11. No explanation given.

12 This is my commandment, that you love one another, as I have loved you.

Ver. 12. No explanation given.

13 Greater love than this no man hath, that a man lay down his life for his friends.

Ver. 13. No explanation given.

14 You are my friends, if you do the things that I command you.

Ver. 14. You are my friends. A wonderful condescension, says St. Augustine, in our blessed Redeemer, who was God as well as man, to call such poor and sinful creatures, his friends; who, when we have done all we can, and ought, are still but unprofitable servants. I have called you my friends, because I have made known to you, &c. We can only understand these words, as St. Chrysostom takes notice, of all things which they were capable of understanding, or which it was proper to communicate to them; for, as Christ tells them in the next chapter (ver. 12.) I have many things to say to you, but you cannot bear them now. (Witham)

15 I will not now call you servants: for the servant knoweth not what his lord doth. But I have called you friends: because all things whatsoever I have heard from my Father, I have made known to you.

Ver. 15. No explanation given.

16 You have not chosen me: but I have chosen you, and have appointed you, that you should go, and should bring forth fruit, and your fruit should remain: that whatsoever you shall ask of the Father in my name, he may give it to you.

Ver. 16. O ineffable grace! For what were we, before Christ chose us, but wretched and abandoned creatures? Such we were; but now we are chosen, in order that we may become good by the grace of Him that hath chosen us. (St. Augustine, tract. 86. in Joan.)

17 These things I command you, that you love one another.

Ver. 17. No explanation given.

18 If the world hate you, know ye that it hath hated me before you.

Ver. 18. If the world hate you. The wicked, unbelieving world, hate and persecute you, as they have done me; remember, that the servant must not desire to be treated better than his master. (Witham)

19 If you had been of the world, the world would love its own; but because you are not of the world, but I have chosen you out of the world, therefore the world hateth you.

Ver. 19. No explanation given.

20 Remember my word that I said to you: The servant is not greater than his lord. If they have persecuted me, **they will also persecute you: if they have kept my word, they will keep yours also.

Ver. 20. Here Christ predicts, that many will be deaf to the words of his Church, as they have neglected to attend to his precepts.

21 But all these things they will do to you for my name's sake: because they know not him that sent me.

Ver. 21. No explanation given.

22 If I had not come, and spoken to them, they would not have sin: but now they have no excuse for their sin.

Ver. 22. They would not have sin, or would not be guilty of sin: that is, they might be excused, as to their not believing me to be their Messias: but after so many instructions, which I have given them, and so many, and such miracles done in their sight, which also were foretold of their Messias, they can have no excuse for their obstinate sin of unbelief. They have hated both me, and my Father: that is, by hating me, the true Son, who have one and the same nature with my Father, they have also hated him, though they pretend to honour him as God. See on this chapter St. Augustine (tract. 81.) and St. Chrysostom (hom. lxxvi.) in the Latin edition, hom. lxxvii. in Joan. in the Greek.

23 He that hateth me, hateth my Father also.

Ver. 23. No explanation given.

24 If I had not done among them the works that no other man hath done, they would not have sin: but now they have both seen, and hated both me and my Father.

Ver. 24. How can this be true, that Christ wrought greater wonders than any one else had ever done? We find recounted in the Old Testament, the miracles of Elias and Eliseus, who raised the dead to life, healed the sick, and brought down fire from heaven; of Moses, who afflicted Egypt with plagues, divided the Red Sea, for the passage of the Israelites, and brought water from the rock; of Josue, who stopped the waters of the Jordan, for the passage of the children of Israel, and in the battle of Gabaon, made the sun and moon stand still; in all which miracles, there appeared a greater manifestation of power, than in any of the miracles wrought by our Saviour, during his ministry. But to this may be answered, that the miracles of our Saviour were much more numerous than those of any of the saints of the Old Testament, even of Moses himself; particularly when we compare the few years which he preached, and manifested the glory of his Father by his miracles, with the long life of Moses: Christ did not preach full four years, whereas Moses governed the people forty years. Again, if the miracles of Jesus were not of so astonishing a nature, at least they always had for their object, the healing of the sick, and the good of the people; which the prophets have given us, as the distinguishing characteristics of the miracles of the Messias. Add to this, the ease and authority with which he performs them, which are most sensible proofs of their superiority. But what chiefly distinguishes his miracles, from those of the other saints, is, that he performed them in proof of his divinity, and of his mission, as the deliverer of Israel: whereas the prophets only perform miracles, as the ministers of the Lord, and as so many voices, which foretold the Messias. Besides, if the ancient saints could work miracles, they never could confer that power upon others, as Christ did upon his disciples, of which the Jews themselves were witnesses, in all the places whither Christ sent his disciples. We omit mentioning his resurrection, which at this time he had not performed, but had already foretold, and which was the greatest miracle that has ever been performed. (Calmet)

25 But that the word may be fulfilled which is written in their law: They have hated me without cause.

Ver. 25. No explanation given.

26 But when the Paraclete is come, whom I will send you from the Father, the Spirit of truth, who proceedeth from the Father, he shall give testimony of me:

Ver. 26. Whom I will send. The Holy Ghost is sent by the Son: therefore he proceedeth from him also, as from the Father; though the schismatical Greeks think differently; (Bristow) otherwise, as Dr. Challoner says, he could not be sent by the Son.

27 And you shall give testimony, because you are with me from the beginning.

Ver. 27. You shall give. He vouchsafes to join together the testimony of the Holy Ghost, and of the apostles; that we may see the testimony of truth, jointly to consist in the Holy Ghost, and in the prelates of the Catholic Church. See Acts xv. 28.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Maestra Barbara Schubert leads the USO into the New Year with a concert of orchestral variations, from the perspective of three different composers. The program features Johannes Brahms’ well-known Variations on a Theme by Haydn, French composer Vincent d’Indy’s eclectic Istar Variations, and Paul Hindemith’s masterful Symphonic Metamorphosis of Themes by Carl Maria von Weber. Together these three works offer a fascinating view into how diverse composers from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries treated this traditional musical form.

A reception will follow. Admission is free. Donations are requested at the door: $10 general, $5 students.

RSVP here: https://www.facebook.com/events/1266098793469630/

Program Notes:

Johannes Brahms: Variations on a Theme by Haydn, Op. 56a (1873)

Johannes Brahms lived and worked at a time when the Austro-German canon of classical music had very recently solidi ed. A new idea of musical historicism (or antiquarianism) was emerging on top of that canon as well: the Bach Society, whose purpose was to edit and publish the complete works of that recently rediscovered Baroque composer, was formed in the year 1850, and a similar Handel Society appeared in 1858. This historicism was fed by the desire for a national pantheon of Classical composers, which grew throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century. This desire was nally ful lled in the 1890s by two gargantuan collected editions: the rst was called Monuments of German Musical Art, and the second was titled Monuments of Musical Art in Austria. In the late nineteenth century, then, the story of classical music in Germany and Austria was a story of roots: nding them, creating them, and then using them to propagate a new national culture.

Brahms’ career lined up perfectly with the development of this national historicism: his rst published opus (his Piano Sonata in C Major) was written in 1853, and his last published opus

(the Bach-inspired Eleven Chorale Preludes for Organ) was written in 1896. Brahms’s Variations

on a Theme by Haydn, Op. 56, emerged against this historicist background. Even in the early nineteenth century, the trio of Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven represented a holy trinity of Austro- German compositional practice. One needs only to look to the famous words of the music patron Count Waldstein, when he funded Beethoven’s studies with Haydn: “You shall receive Mozart’s spirit from Haydn’s hands.” For Brahms to write a set of variations on Haydn, then, was like an act of intercession, intended to connect oneself to the musical divine.

Brahms took the theme for this work from a manuscript shown to him by an early Haydn scholar, Carl Ferdinand Pohl. It was the second movement of a piece for winds, and above it was written “St. Anthony Chorale.” Brahms was enamored with the chorale’s expansiveness, and set out to write a set of variations with the chorale as its theme. Brahms thought of variation form as a balancing act: on one hand, one needed a unique theme (but not odd enough to be distracting); and on the other, one needed inventive variations (which should still be recognizably related to the theme). With the new backdrop of nineteenth-century historicism, there was an additional factor to balance: a set of variations on a classic theme ought to pay its respects to the greats without being overly conservative — and it ought to innovate but it could not leave its theme behind. Brahms had previously written a set of piano variations on a theme by Handel, which demonstrated his ability to write music that blossomed from the hardy seed left behind by a great master. He hoped that this Haydn chorale would be just as fertile for a new composition.

It might be surprising, then, to learn that Haydn actually had nothing to do with the wind version of the “St. Anthony Chorale” that caught Brahms’s imagination. Musical misattributions were common before the twentieth century for two reasons: first, copyright laws were few and far between; and second, much music was copied by hand and disseminated in manuscript form without careful oversight. Musicologist H.C. Robbins Landon has purported that this “St. Anthony Chorale” was in fact composed by Haydn’s student, Ignaz Joseph Pleyel. (And in any case, the original inspiration for the chorale tune did not come from Haydn: the chorale was based on a hymn sung by pilgrims in Padua, where the tongue of St. Anthony was kept as a relic.) Brahms’s theme, then, lacks the authentic connection to Haydn that Brahms had hoped would tie him to a venerable tradition.

Of course, none of this changes the sheer joy of listening to Brahms’s Variations. The listener’s curiosity is immediately kindled by the opening statement of the theme: it is organized into five- measure phrases, which thwart our deeply ingrained, foursquare Classical expectations. Brahms preserves this unique detail in every one of his eight successive variations. The melody of the theme also provokes curiosity: it’s an oddly static melody, mostly hovering around the same notes (D and E- at above it).

The first variation takes us into definitively Brahmsian territory: over a static bass we hear a bustle of triplets in the strings, set against duplets in the other instruments. This sort of melodic three- against-two is one of Brahms’s favorite maneuvers, as many beleaguered pianists know. The second variation gives us the first hint of storm and stress: sharp timpani strokes are followed by quiet flurries of motion in the strings. The third variation soothes the anxiety of the previous one with sinuous lines played by the woodwinds over a placid string accompaniment. The fourth variation grows out of the previous one, with the same hushed lyricism now cast within the less con dent minor mode. The fifth variation is a lively Poco presto, serving the same function as a scherzo movement within classical sonata form. In the sixth variation the horns take center stage, playing a version of the opening melody that is decorated with skipping sixteenth notes. Here Brahms changes the underlying harmonies of the theme, closing the initial phrases with unexpected cadences in a minor key. The seventh variation has a kind of courtly magnanimity, with slow lilting rhythms recalling the Baroque siciliano dance. The eighth variation, which calls for the strings to play with mutes, casts us into a state of mysterious groundlessness. We regain our footing with a stately passacaglia finale. (A passacaglia is a form in which the bass line repeats the same figure over and over, while the other parts play constantly-changing countermelodies over it.) This passacaglia leads us seamlessly back to the original St. Anthony Chorale, played triumphantly by the whole orchestra to cap the work.

Vincent d’Indy: Istar: Variations Symphoniques, Op. 42 (1896)

Vincent D’Indy’s Istar: Variations Symphoniques, Op. 42, is based on a story from the Epic of Gilgamesh that describes the descent of Ishtar, goddess of love, into the underworld in order to save her imprisoned lover. Ishtar is forced to remove a piece of jewelry or an item of clothing at each of the four gates through which she passes. This slow and methodical disrobement was the inspiration for d’Indy’s reversal of variation form: instead of beginning with the theme, d’Indy begins with his most far-flung variation. Each subsequent variation is pared-down and re ned, and the piece ends with the “naked” theme. A concertgoer who is familiar with Richard Strauss’ opera Salome (with its infamous “Dance of the Seven Veils”) might expect a garishly orientalist Ishtar — but not so. D’Indy’s Istar is much closer in character to the nineteenth-century orchestral genre called the “symphonic poem,” which is best represented by Liszt’s allegorical works of the 1850s. Istar projects this same sort of allegorical abstraction. We do not hear the urgency of a determined goddess here; instead, we hear the story of ornament and simplicity, told in a late- romantic Franco-German voice.

This piece’s unusual form, and the myth that inspired it, is worth examining. Why would the Babylonian Ishtar be a promising subject for a French symphonic piece in the German genre of the “symphonic poem”? What would have made it feasible — or necessary — for such a piece to be penned in fin-de-siècle Paris?

Istar was composed in 1896, during a period of European fascination with ancient cultures of the eastern Mediterranean. As the Ottoman Empire began its slow dissolution over the late nineteenth century, the Europeans swept in — and when they left, they took local artifacts and mythologies with them. The tale of Ishtar (from the Epic of Gilgamesh) is one of those mythologies. The Gilgamesh story was first translated into English by the Assyriologist George Smith, who attracted international attention by comparing the flood myth in the Epic to Noah’s flood in the Bible. Smith further declared that Gilgamesh was the same figure as Nimrod of the Old Testament. These similarities to more familiar European myths were what put early Assyriology into the public eye.

Indeed, the story of Ishtar descending into the underworld is remarkably similar to the myth of Orpheus from Ovid’s Metamorphoses: Orpheus was a hero who plied his way into Hades with the musical power of his lyre to save his beloved Eurydice. The Orpheus myth appears throughout the history of European music like a leitmotif. Claudio Monteverdi’s Orfeo (1607), for example, was a seminal early opera. Likewise, the musical reformer Christoph Willibald Gluck also turned to Orpheus when he wrote Orfeo ed Euridice (1762), his first opera written in a new, streamlined style. Victorian readers of the Gilgamesh epic were quick to point out the similarity between Ishtar and Orpheus — and d’Indy’s Istar, in turn, appears to triangulate the distance between the Babylonian Ishtar and the Greek Orpheus. While Monteverdi’s Orfeo began with simple pastoral forms that became more formal, more ornate, and more filled with pathos as Orpheus journeyed into the world of the dead, D’Indy does the exact opposite: his most inventive material comes at the beginning, with ravishing orchestration for the initial variations, gradually lessening as Istar’s (literal) divestment proceeds, and resulting in a knowing and elegant simplicity in the final section of the work. D’Indy’s Istar, then, is a reversed Orpheus.

Paul Hindemith: Symphonic Metamorphosis of Themes by Weber (1943)

Paul Hindemith began his work on the Symphonic Metamorphosis of Themes by Carl Maria von Weber shortly after leaving Germany for the United States. In Germany, the composer had alternated between resisting the Nazi government and making concessions to them: thus, a man whose music was officially catalogued as “degenerate” could at the very same time receive praise from Josef Goebbels, who praised Hindemith as the foremost composer of his generation. Despite Hindemith’s popular success, though, political tensions mounted. Wilhelm Furtwängler, the legendary conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, was even forced to step down from his post temporarily because of his vigorous defense of Hindemith. The composer emigrated to the U.S. in 1940, and joined the music faculty at Yale University.

The Symphonic Metamorphosis began its life as a series of sketches for a ballet. Hindemith had planned to collaborate with Léonide Massine on a ballet based on the music of classical composer Carl Maria von Weber, but Hindemith and Massine’s artistic differences over the staging eventually killed the project. Hindemith refashioned his sketches into the orchestral piece we hear tonight. The themes that Hindemith selected for “metamorphosis” were all fairly obscure Weber tunes: three of the Metamorphosis’ movements were taken from Weber’s Op. 60 collection of piano duets, and the middle scherzo was based on Weber’s music for the Friedrich Schiller play Turandot. One might speculate that Hindemith chose these little-known and little-appreciated themes so he could showcase his compositional skill. (You might recall the balancing act that Brahms was faced with: don’t pick a theme that will steal the show from your variations!)

The Symphonic Metamorphosis ultimately turns Weber’s original pieces into empty molds that are then filled with Hindemith’s inventive fire and flash. The first movement, a raucous Allegro, transforms a Turkish march by Weber into something far more foreboding. The second movement, crafted from music originally for Turandot, is a set of variations on a Chinese melody (drawn by Weber from Rousseau’s Dictionnaire de musique of 1768). The Chinese tune is repeated over and over, to create a feverish perpetual motion machine whose ceaseless whirring is underscored by the almost never-ending trills in the woodwinds. By the end of the movement, this off-kilter tune completely exhausts itself of significance: it’s as if one had repeated a word so many times that the word is now a string of unfamiliar sounds. The third movement, a soothing Andantino, hews closely to the original structure of Weber’s piano duet but adds two new elements: first, a cushion of harmony in the strings, and second, a final flute solo that is foreign to Weber’s style. The final movement is yet another march, introduced with horn-calls and martial beats of the snare drum. One of the goals of the Metamorphosis was to show the new possibilities that were unlocked by the huge, post-Romantic, twentieth-century orchestra. The piece requires an extensive percussion section: over and above the standard percussion instruments we hear a tambourine, gong, wood blocks, tom-toms, and chimes. Hindemith’s use of percussion gives every movement an edge of danger.

The bizarre exoticism of the “Turkish” first movement and “Chinese” second movement are worth exploring. The Ottomans were a legendary military opponent of the Habsburgs for the entire existence of the Habsburg empire, and it was commonplace for Biedermeier-era composers to mimic the sounds of a Turkish military band (think of Mozart’s “Rondo alla Turca”). It’s not surprising, then, to encounter a Turkish march by Weber. But why would Hindemith choose a Turkish march for his Metamorphosis? The Turandot scherzo is even more confusing: Weber wrote his music for Schiller’s play Turandot, which was in turn based on an eighteenth-century commedia dell’arte play by Carlo Gozzi, who in turn was inspired by the Sassanid Persian tale of Princess Turandokht (“daughter of Turan,” Turan being the ancient name for Central Asia). European whimsy gradually transformed Turandokht into the Chinese Turandot, the thwarted empress of Puccini’s eponymous opera.

And what can we make of Hindemith’s putative homage to Weber? Weber was a composer idolized in his own time, but after a few generations he was remembered only as a composer of a few famous operas. It might surprise the reader to learn that the nineteenth-century critic A. B. Marx wrote that Weber’s work was on par with Beethoven’s: it “often surpassed [Beethoven’s work] in grandeur and elaboration.” But Hindemith isn’t bowing to the old master, Carl Maria von Weber. His piece does not seem to highlight the original features of Weber’s music in same the way that Brahms’s Variations paid tribute to the simplicity of “Haydn’s” chorale. Neither does Hindemith scorn Weber: even though Hindemith’s transformed final product is overwhelming in its fire and brilliance, it still seems to depend on the structure of the Weber pieces on which it was based. (The first movement of the Metamorphosis, for example, preserves the exact same phrase structure as Weber’s original.) Finally, Hindemith’s treatment of the Chinese melody from Turandot raises questions: this is not a metamorphosis of Weber, but a metamorphosis of Weber’s original metamorphosis. In sum, Hindemith’s Metamorphosis doesn’t point backwards to its original source material in the way Brahms’ piece does — but it doesn’t call attention to its own structure like d’Indy’s Istar, either.

The intended subject of this Metamorphosis isn’t the beginning of the transformation, or its final product: it’s the process of metamorphosis itself — a process that inadvertently creates a formless but threatening Orientalized “Other.” (A painter might set out to turn the story of Ishtar into

a painting, but he would shudder to imagine the real Ishtar who eluded his brushstrokes.) This “Other” emerges as a threat only after it has passed through the ears of Rousseau, of Schiller, of Weber, and finally through Hindemith’s ears to us — like a racializing game of “telephone” (a game that was once called “Chinese whispers”).

Hindemith’s Metamorphosis, then, is an object lesson in how music is inextricably bound up in the political conditions of its creation. Is it possible, as a composer, to connect your music to the past in just one specific way, and to scrub away all other traces of intervening history? Is it possible to write music based on a theme penned by a composer as monolithic as Haydn, without calling attention to a Bloomian “anxiety of influence”? Can the genealogy of a melody, or of a myth, be wiped away to create a clean musical slate to work on? We listen to Variations on a Theme by Haydn, though, whose theme has nothing to do with Haydn, and we suspect the answer is “no.”

— Notes by Andrew Malilay White Ph.D. Student in Music

4 notes

·

View notes