#sir thomas parr

Text

Henry VIII’s 26 Knights of the Bath

The King has proclaimed that all who claim to do services on Coronation day shall be in the White Hall at Westminster Palace, 20 June next, and has authorised the Earl of Surrey, Treasurer of England, the Earl of Oxford, Sir John Fyneux, Chief Judge, Sir Thomas Englefeld, and others to determine claims. He has ordered 26 honorable persons to repair to the Tower of London on 22 June, to serve him…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Becoming Elizabeth + Textposts (the grand finale)

Bonus:

#becoming elizabeth#edward vi#elizabeth tudor#john dudley#jane grey#mary i tudor#katherine parr#henry grey#Edward Seymour#sir pedro#thomas seymour (derogatory)#feat. stephen gardiner#theyre all awful ur honour#cant wait for the finale so my suffering will end

216 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The priest is speaking wise words!

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

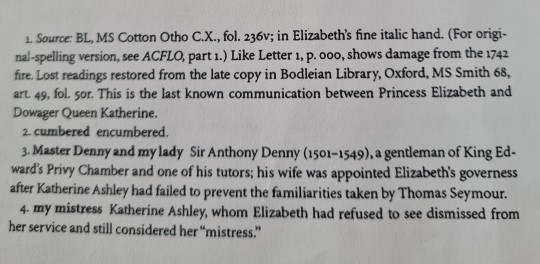

Last known letter from Princess Elizabeth to Katherine Parr, July 1548. Despite being sent away due to the Seymour scandal, Elizabeth continued to correspond with the Queen and in this letter wishes the Queen well for the birth of her forthcoming child. Sadly KP did not survive and died of childbed fever 🙁

#becoming elizabeth#princess elizabeth#queen elizabeth#katherine parr#thomas seymour#scandal#sudeley castle#childbed fever#kat ashley#sir anthony denny#👑🌹#alicia von rittberg#jessica raine#tom cullen

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

“An assessment of Anne (Boleyn) and the Reformation must commence with an evaluation of her own religious views. Unlike Henry’s sixth wife, Katherine Parr, Anne wrote no religious works, so we lack much direct evidence from which to assess her convictions. We instead rely on the assertions of others and what can be surmised from her behaviour and belongings. It is nonetheless clear that Anne was by no means a kind of proto-protestant. For instance, when Thomas Revell tried to present her with his translation of François Lambert’s radical Farrago Rerum Theologicarum—which included scepticism about the real presence of Christ in the eucharist, and detailed the socially disruptive implications of the priesthood of all believers—she declined his request, saying “she would not trouble herself” with the book. Likewise, Anne’s comments during her imprisonment imply that—at least during this difficult period—she maintained many orthodox views. Sir William Kingston, constable of the Tower, wrote to Cromwell that she spoke of retiring to a nunnery; that she asked whether she would go to heaven, for she had “done mony gud dedys in my days”; and that she “meche desyred to have here in the closet the sacrament,” suggesting that she held traditional views on transubstantiation, the issue which Henry saw as the test of sound belief.

There remains much evidence, however, that Anne had evangelical sympathies. For example, Cranmer, who knew the Queen well, noted the “love which I judged her to bear towards God and his gospel,” when writing to Henry following her arrest in May 1536, and Richard Hilles lamented her loss in 1541 as one of the “sincere ministers of the word” who had been taken away. Yet, perhaps the most telling evidence of Anne’s personal piety comes from the books that she owned. These included a copy of William Tyndale’s 1534 edition of the New Testament, which was banned and considered to be a heretical work, and a part copy, part English translation, of Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples’s Epistres et Evangiles, a work condemned by the Sorbonne for its potential Lutheran echoes. Thus, while Anne cannot be described as a ‘protestant’—a term that did not become naturalised in England until after 1553—she seems to have been genuinely interested in religious reform and evangelical issues.

Anne’s impact on the Reformation is most obvious with Henry’s break from Rome. This was recognised in Anne’s own lifetime; when told that there was no pope, but only a bishop of Rome, one Henry Kylbie replied that “this business had never been if the Kinge had not maryed Anne Bullen.” Although it was Henry’s desire to annul his first marriage to marry Anne that caused conflict with the papacy, the Boleyns provided more than a spark for this clash. They offered patronage to academics who worked on the campaign for Henry’s annulment, including Thomas Cranmer, the future Archbishop of Canterbury, and Edward Fox, the future Bishop of Hereford; they took a keen interest in the progress of Henry’s “Great Matter”; and they seemingly furnished Henry with evangelical literature, with Anne reportedly introducing him to both Simon Fish’s virulently anticlerical Supplication for the Beggars and Tyndale’s Obedience of the Christian Man, which argued that papal claims to independent power were bogus and unscriptural. While the contribution these works made to the elaboration of the royal supremacy has been doubted, they may well have helped, and can hardly have hindered matters. In these ways, Anne and her family played an important part in encouraging the rejection of papal authority and achieving Henry’s Break from Rome, a fundamental element of the English Reformation.

Anne also facilitated religious reform by furthering the careers of evangelicals. Writing to Elizabeth I in 1559, Alexander Ales hailed “the evangelical bishops whom your most holy mother had appointed from among those schoolmasters who favoured the purer doctrine of the Gospel.” Who were these bishops? While William Latymer asserted that her influence lay behind the promotion of Thomas Cranmer to Canterbury, Hugh Latimer to the bishopric of Worcester, Nicholas Shaxton to Salisbury, Thomas Goodrich to Ely, and John Skip to Hereford, the evidence is clearest in the cases of Latimer and Shaxton, who Foxe also thought she “placed” and “preferred” to their sees. Although Anne certainly did not ‘appoint’ Latimer and Shaxton to their dioceses, she undoubtedly assisted them, lending each £200 to pay their first fruits to the King after their elevations, and their preferment was plausibly due to what Latymer described as her “continuall mediacione.” Anne herself recognised her links to these bishops, speaking in the Tower of “my bysshoppys.” Her part in the promotion of these men to the episcopal bench was important, for it meant they could wield the power of episcopal office to promote fellow evangelicals, pursue reform in their dioceses, and frustrate the efforts of their opponents.

Anne also influenced lesser clerical appointments. She employed a series of evangelical clergy as her chaplains, including Latimer and Matthew Parker. She also sought appointments for her favoured clergymen elsewhere, and was prepared to pressure them into taking them up and making the most of them, as in May 1535, when she addressed Edward Crome concerning the parsonage of St Mary Aldermary in London, which she had “obtained for him.” She exhorted him to make “no farther delays in this matter, but to take on … the cure and charge of the said benefice,” for she desired “the furtherance of virtue, truth, and godly doctrine, which we trust shall not be a little increased, and right much the better advanced and established, by your better relief and residence there.” The indefatigable commitment that some of the clergy she appointed showed to driving reform at a local level is clear in the case of William Barlow, who she made prior of Haverfordwest in 1534. From his position, Barlow “endeveryd … with no smalle bodely daunger agenst Antichrist, and all his confederat adherentes, sincerely to preche the gospell of Christ,” arousing much hostility from the local clergy. Anne’s promotion of such clerics was significant. Not only did men like Barlow show great zeal in fighting for reform within their spheres of influence, but her promotion of men as her chaplains also proved an important step in the careers of individuals like Latimer, who became Bishop of Worcester in 1535, and Parker, who became Elizabeth I’s frist Archbishop of Canterbury in 1559. This was attested by Parker himself, who wrote to William Cecil, Lord Burghley, in 1572, professing that “if I had not been so much bound to the mother [Anne], I would not so soon have granted to serve the daughter [Elizabeth] in this place.’

While previous queens had often interceded for those facing punishment, Anne used her intercessory role in to protect those interested in reform. For instance, in 1528 she wrote to Cardinal Wolsey, beseeching him “to remember the parson of Honey Lane for my sake.” This was a reference to either Thomas Forman (rector of All Hallows, Honey Lane) or Thomas Garrett (curate of the same church), who were both implicated in the trade of evangelical books. Likewise, in May 1534, she wrote to Cromwell asking for Richard Herman, one of the principal promoters and financial sponsors of Tyndale’s New Testament, to be restored to his position, after hearing that he had been expelled from his “fredome and felowshipe of and in the Englishe house” of Antwerp, because he helped “the settyng forthe of the Newe Testamente in Englisshe.” Anne may have acquired a reputation for lending aid in such matters, which might explain why Thomas Alwaye sought to petition her in 1530 when imprisoned for his involvement in buying English New Testaments and other prohibited books. While the evidence is not certain, Anne’s patronage potentially had longer-lasting repercussions, as individuals like Thomas Garrett later became troublesome evangelical preachers.

Anne was thus clearly an important figure in the early stages of evangelical reform in England. She was by no means an omnipotent proto-protestant—that evangelicals like Thomas Bilney and John Frith were burnt between 1531 and 1533 reveals limits to either her beliefs or her infuence. Yet, individuals did not need to be all-powerful to encourage religious change: Thomas Cranmer’s failure to prevent the passage of the Six Articles in 1539 did not hinder his influence in the ecclesiastical politics of the early Tudor period. Nor did they have to be fully fledged evangelicals to have sped the course of reform. That Henry VIII himself published Assertio Septem Sacramentorum in 1521 (a rebuttal of Martin Luther’s anti-papal De Captivitate Babylonica), remained devoted throughout his life to the Blessed Sacrament, and consistently rejected the teachings of Luther and Huldrych Zwingli does not invalidate his centrality to the reforms of his reign. Moreover, Anne’s infuence on reform need not be at the expense of others. The course of religious change in sixteenth-century England was not simply shaped by monarchs, devout conservatives like John Fisher, or devout evangelicals like William Latimer, but also by many who lay between these extremes, like Stephen Gardiner, who argued for Henry’s divorce and accepted the Dissolution of the Monasteries, but fercely defended transubstantiation. Anne—as a promoter, defender, and supporter of evangelicals, who played a significant part in instigating the Break from Rome—was one of the most important of these individuals.

- Chloe Fairbanks and Samuel Lane, “Anne Boleyn: Traditionalist and Reformer” in “Tudor and Stuart Consorts: Power, Influence and Dynasty”

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Maud Green (6 April 1492 – 1 December 1531) was an English courtier. She was the mother of Catherine Parr, the sixth wife of King Henry VIII of England. She was a close friend and lady-in-waiting to Catherine of Aragon. She was also co-heiress to her father, Sir Thomas Green of Green's Norton in Northamptonshire along with her sister, Anne, Lady Vaux.

92 notes

·

View notes

Note

What’s the real history with Thomas Seymour proposing marriage to Elizabeth after Catherine’s death?

I’m confused seeing people say real life Elizabeth didn’t (or wouldn’t have) accepted Seymour’s proposal like in Becoming Elizabeth because she was deliberately ambiguous with her answers about him wanting to marry her. Is that from her saying she would never marry without permission from the Privy Council? I assumed that was from the Tyrwhitt interviews and she meant ‘obviously I wasn’t planning a marriage with him cause if he’d suggested it I’d have said we had to ask the council’. Because why would she need to give some kind of ambiguous or cautious answer so as to not incriminate herself by admitting knowledge that he wanted to marry, unless she had at the least entertained the idea in some way.

Hello anon - first of all i'm sorry for taking to long to reply, i've been at work and i wanted to try and give a proper answer rather than just giving you a short one.

Theres belief that Thomas Seymour originally had asked Elizabeth to marry him in February 1547 which she rejected him claiming she was still in mourning for her father - however this comes from a 17th Century historian and not a contemporary so therefore we can't verify that this actually happened.

After Catherine Parr's death in 1548, Seymour doesn't immediately dissolve her household and decides that they should now attend Lady Jane Grey, but suspision began to grow he may be looking for a new wife.

Kat Ashley, Elizabeth's governess, also encourages Elizabeth to write to Seymour to give her condolences on the death of Catherine, however Elizabeth declined to do so, believing that he didn't need them, she probably also wanted to avoid anymore rumours spreading.

Now unlike in the show, Elizabeth and Thomas Seymour do not see each other again after she leaves Chelsea for Cheshunt.

When she comes to London for Christmas 1548, she finds her residence of Durham Palace had been turned into a mint by the Duke of Somerset, Seymour loaned her Seymour Palace and met Elizabeth's cofferer, Thomas Parry (quick note - where is he in BE?). In this meeting, Seymour begins asking Parry about Elizabeth's finances. When Henry VIII died, he left his Mary and Elizabeth a £10,000 dowry if they married. Parry answered his questions as much as he could and then reported to Elizabeth what Seymour was asking. During this conversation, Parry outright asks Elizabeth if she would marry Seymour if the council did not object, and before answering she is said to have looked visibly displeased. Here we get her first ambiguous answer when she says; 'When the time comes to pass i will do as God shall put in my mind.'

On New Years 1548/9 Thomas Parry and Kat Ashley begin to gossip on the subject of Elizabeth and Seymour, here Kat tells Parry why Elizabeth was sent away from Chelsea to the Denny's at Cheshunt.

Kat Ashley also began encouraging Elizabeth to consider marrying Seymour and she was pretty persistent on the matter, but Elizabeth again did not give a straight answer, saying that; 'Though he himself would preadventure have me, yet i think the council will not consent to it.'

Soon rumour began to spread of Seymour's plans and he ended up having a confrontation with a member of the Privy Council, John Russell, Earl of Bedford (not Henry Grey as shown in BE), who told Seymour that if he went through with them it could be his 'utter undoing'.

Now we know what happens next, Seymour breaks into Edward VI's chambers, shoots his dog and is arrested and sent to the Tower. Kat Ashley and Thomas Parry are also arrested and sent to the Tower. Elizabeth is questioned by Sir Robert Tyrwhitt about her involvement with Seymour and any possible plans for marriage. In defense of Kat Ashley, although admitting that she had acted irresponsibly, she says that Kat would; 'never have me marry, neither in or out of England, without the consent of the King's Majesty and the Council's'.

During her interrogation, she writes to the Duke of Somerset concerning rumours of her also being imprisoned in the Tower and that she is pregnant with Seymour's child. She refers to these rumours as 'shameful slanders', and asks to come to court so that she may, 'show myself there as i am'. She also asked Somerset to take actions against rumours, which he agreed to do, if she could name those who spread them.

Now the ambiguous answers, her rebuff of Kat's persistance, looking displeased when Parry mentions marrying Seymour and her calling the rumours 'slanders' to me does not seem like she actually wanted to marry Thomas Seymour. Not to mention, there is also evidence that she was made uncomfortable by Seymour's advances, including getting up early to avoid him and writing 'thou touch me not' on a letter.

People do like to say that Elizabeth may have had a crush on Seymour, and blushed at his name being mentioned, she could very well have, but this would not have made her any less of a victim. On the other hand, blushing does not always mean having a crush on someone, it could have been because of discomfort or shame as well.

The ambiguous answers were also something Elizabeth always gave towards the question of marriage, especially after she becomes queen and the council begin pressuring her to marry to secure the succession. It may have been because she did not want to marry at all, which is something she first says to Robert Dudley when she was just eight years old. I don't personally think her ambiguous answers were to avoid her incriminating herself. She was cautious, something the show truly failed to show and did a big injustice to her.

I'm so sorry for the long answer but i wanted to answer as best as i could! If i have made any mistakes/incorrect statements please feel free to correct me!

Sources:

Elizabeth The Great, Elizabeth Jenkins (1958)

Elizabeth I, Anne Somerset (1991)

Elizabeth: Apprenticeship, David Starkey (2000)

Elizabeth and Leicester, Sarah Gristwood (2008)

#answers#im also sorry for citing david starkey#but unfortunately his account of the seymour incident is one of the better ones#elizabeth i#tw: csa#becoming elizabeth#thomas seymour#elizabeth tudor

61 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Day 8: Catherine Parr!

Catherine Parr was born in 1512, to a family of minor English nobility. She was reasonably well educated as a child, and continued her education as an adult; she would eventually speak five languages, and was the first woman in England to publish a vernacular book under her own name.

She was married young, first to the sickly Sir Edward Burgh and then the middle-aged John, Lord Latimer. During a rebellion against Henry VIII, her husband was captured, and may have joined the rebels; he avoided the charge of treason but spent the rest of his life under a cloud. Upon his death, Catherine became an extremely wealthy widow. She joined the household of Lady Mary, Henry VIII’s daughter, and was courted by Sir Thomas Seymour - and then, to her likely horror, by the king.

Catherine became Henry’s sixth and last wife. During her marriage, she published two books, bonded with her stepchildren, and served as regent during Henry’s last French war. She also barely escaped the violent fate of two of her predecessors when Henry grew suspicious of her Lutheran leanings.

After Henry’s death, Thomas Seymour resumed his courtship of Catherine, and the two married. Her former stepdaughter, Elizabeth, came to live with them, and Catherine, for the first time, was pregnant herself. She seemed to have finally found stability.. but it wasn’t to be.

Seymour was sexually abusing Elizabeth, and Catherine, who had naively encouraged what she thought was a playful relationship, separated from him, while Elizabeth was sent to another household. The stress likely contributed to Catherine’s death in childbirth a few months later; her daughter followed her to the grave.

#catherine parr#history#english history#tudor history#the house of tudor#awesome ladies of history#october 2022#my art#charcoal#csa tw

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

I don’t know about Becoming Elizabeth and why it’s trending, so I decided to do some research.

Becoming Elizabeth focuses on exploring the young future queen’s relationship with the older Sir Thomas Seymour, brother of her dad’s third wife, Jane Seymour, and the uncle of King Edward VI, who went on to marry Henry’s fourth and final wife, Catherine Parr. Elizabeth and Seymour were said to have had a romantic affair while the future queen lived with Catherine, who became Elizabeth’s guardian after the King’s death. On the show, Thomas is often seen hopping into Elizabeth’s bed, tickling her, and undressing her in front of the royal servants—all of which was documented in letters Reiss had read in preparation for the show. — The True Story Behind Starz’s Becoming Elizabeth

Are they romanticising Thomas Seymour and Elizabeth? I thought she was young at that time.

Thomas Seymour engaged in romps and horseplay with the 14-year-old Elizabeth, including entering her bedroom in his nightgown, tickling her, and slapping her on the buttocks. Elizabeth rose early and surrounded herself with maids to avoid his unwelcome morning visits. Parr, rather than confront her husband over his inappropriate activities, joined in. Twice she accompanied him in tickling Elizabeth, and once held her while he cut her black gown “into a thousand pieces”. — Elizabeth: Apprenticeship, p. 69

Elizabeth was 14-years-old. OH MY GOD. Also, she didn’t like his advances. If she liked it, why would she surround herself with maids every time he visits?

I’ve watched the STARZ’s The White Queen and I shipped Richard III and Anne Neville. They’re the only reason why I watch the show. And what did they do? Make Richard sleep with his niece, Elizabeth of York -- which is based on a rumor that he intended to marry her because his wife, Anne Neville, was dying and they had no surviving children.

In reality, King Richard III only loves his wife. Why else would he renounced Warwick’s land to George?

In order to win George’s final consent to the marriage, Richard renounced most of the Earl of Warwick’s land and property including the earldoms of Warwick (which the Kingmaker had held in his wife’s right) and Salisbury and surrendered to George the office of Great Chamberlain of England. — Richard the Third

After her death, he negotiates a double marriage with King John II of Portugal -- Richard with Joanna (Joan), and Elizabeth with their cousin Manuel.

Soon after Anne Neville’s death, Richard III sent Elizabeth away from court to the castle of Sheriff Hutton and opened negotiations with King John II of Portugal to marry his sister, Joan, Princess of Portugal, and to have Elizabeth marry their cousin, the future King Manuel I of Portugal. — “The Portuguese Connection and the Significance of the ‘Holy Princess’,” The Ricardian, Vol. 6, No. 90

They always do this, ruining real history for the sake of drama.

I think so many of us hoped that because Becoming Elizabeth wasn’t based on a PG novel and the show was not headed by Emma Frost that things would be different.

Apparently we were asking too much for Elizabeth’s abuse by Seymour when she was freaking fourteen to not be romanticized.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Name Game: the title of “Lady”

The mother of Anne Boleyn is often referred to as “Lady Elizabeth Howard”. That’s NOT correct! Why? In those times, if your name was “Lady Elizabeth Howard”, you would have been the wife of a knight with the surname Howard. Elizabeth Boleyn’s mother, born Elizabeth Tilney, was married to Thomas Howard in 1472. At that time, she simply took on the surname Howard. In 1478, Thomas was knighted and…

View On WordPress

#3rd Lord Latimer#Alice Neville#anne boleyn#catherine parr#Dowager Queen Katherine#Elizabeth Boleyn#Elizabeth FitzHugh#Elizabeth Howard#henry viii#katherine parr#lady alice fitzhugh#Lady Elizabeth Boleyn#lady Elizabeth Howard#lady latimer#lady vaux#Queen Katherine Parr#sir thomas parr#the title of lady#titles of Catherine Parr#Tudor titles#william parr

0 notes

Photo

Becoming Elizabeth + Textposts (Part 3)

Bonus:

#becoming elizabeth#elizabeth tudor#mary i tudor#henry grey#sir pedro#katherine parr#edward seymour#thomas seymour (derogatory)#feat. stephen gardiner#okay NOW ill stop clogging the tag with these

193 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Thomas is a quick learner. 😉

#Becoming Elizabeth#becomingelizabethedit#Catherine Parr#Sir Thomas Seymour#Princess Elizabeth#Queen Elizabeth I#BES1E1#BES1E5#parallels

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

alice seymour, nee parr. viscountess beauchamp / the avenging magdalene - shunned for her licentious mouth, upon her bed lies a house for scandal & rumour, she returns to court seeking fury

penned by velvet for @bloodydayshq

BULLETPOINTS:

name: alice seymour nee parr

age/dob: thirty-eight / february 20th 1521

status/rank: viscountess beauchamp

country of origin: england

place of birth: blackfriars, london

birth order: third youngest

mother & father: marquess thomas parr of northampton & lady maud parr nee green✟

siblings: utp parr, marquess of northampton (41), utp parr, lady parr (39)

sexuality: bisexual

horoscope: pisces

virtues: leaderly, cunning, independent

vices: irritable, coquettish, hostile

marital status: married to viscount beauchamp (m. 1545)

issue: arthur seymour (b. 1549), catherine seymour (b. 1553)

alliance(s): the greys (by marital bonds-politics), the seymours (marriage, tense), the spanairds (maternal bonds)

adversaries: the boleyn family, the tudor crown (ish), the court (fully)

TIMELINE:

1521 Birth in Blackfrairs, London to Maud & William Parr, Marquess of Northampton & Lady-in-Waiting to Catherine of Aragon

1525 Death of William Parr, her brother inherits, Alice & her sister become wards to the crown at Bridewell Palace, Blackfriars

1526 Is moved to her Uncle Sir William Parr ‘s Rye House, Hertfordshire for her education whilst her mother remains at court

1531 Her mother dies from the sweating sickness, her will is in place and Alice inherits many portraits, jewels and enough for a dowry of her own

1532 Marriage of Anne Boleyn & Henry VIII

1536 Death of Catherine of Aragon, this is where her hatred for the Tudors/Boleyns begins

1538 Moves to London, where she becomes Lady in Waiting to Anne Boleyn by the arrangement of her Uncle, she detests it and begins a series of secret missives between herself and Mary Tudor, & Anti-Reformist parties

1545 Marries Viscount Beauchamp by the arrangement of her Uncle, she misses the arrest warrant for Anne, and returns to court whilst she detesting her husband for not supporting his brothers

1549 Leaves court to give birth to Arthur Seymour, returns with a fighting vigour and swears her fidelity to her husband despite rumours that she has been licentious and promiscuous with both the young Prince William & many other men at court

1550 Remains at court as part of Anne Boleyn’s circles, probably flirts with henry Tudor whilst she can to get stuff? Begins an absent re-construction of Wulfhall to benefit her son's inheritance, but its an uphill battle since Seymour is hardly a name honoured by the people

1553 Gives birth to Catherine Seymour

1557 Henry VIII dies, attends the coronation of William III with the Grey & Seymour clans

1559 Attends the marriage of Anne Boleyn & Thomas Wyatt

BIOGRAPHY:

Kendal Castle was crumbling, or rather, it had crumbled. As the ancestral House of Parr, one would've thought someone would have paid greater attention to the wellbeing of a home that could've last a thousand years, for instead of being brought into the world beneath the roof of a seat that had long been held by their family since the time of the Caput baroniae, Alice was born amongst the city of London, Blackfrairs to be exact. The youngest of three, the only thing stammered between uneasy lips was the fact that shes was then owed a dowry by the behest of a father who had grown all too comfortable with cards at the Palaces of the English court. So, when wrapped in lavender scented linens, she was pushed into the arms of a wet nurse so both parents could return to their habits and pleasures.

Thomas Parr was a fine, intelligent mind - he had once been the principle to Lady Margaret Beaufort's school at Collyweston and had long since taken grand advantage of his intellect to pursue mathematics and theology before being risen to the role of Master of the Wards, Master of the Guards and Comptroller to the King. Maud Green was met on a similar playing field as a trusted member of the revolving ladies who waited upon Catherine of Aragon, with her own rooms to enjoy and great luxuries passed upon her by the kindness of the Queen. Their marriage was one of fine dining, riveting conversation and kind looks passed over the heads of their peers. First came their son, then a daughter, and then finally Alice.

Brought up to relish the mind and what could come from nourishing cunning, Alice had been wise from the start. For though their father died when, their mother used her connections to have herself and her children established in the rooms of Bridewell Palace, Blackfriars, so she could keep her proximity to the Queen and her offspring could continue their wellbeing beneath her quick gaze. Though, they only remained a year, for Alice at only five years of age, was found in the arms of her father's brother, William Parr, escorted alongside her sister towards Rye House, Hertfordshire, for their education and happiness.

Of course, it would've been foolish to live such a youthful childhood amongst the humdrum of an English Court, thereafter became the hotbed of fury concerning the dissolution of the marriage between the King and Queen. And though their mother, the ever faithful Lady Maud, remained by her Mistress' side in an act of complete loyalty to both the Pope and the safety of Catherine, Maud soon caught the sweating illness. Alice, who had grown to enjoy the great expanse of land nurtured by her Uncle, running alongside her siblings whilst cultivate a strong, unbreakable friendship with them both, soon learnt that they were no longer as safe as before, but rather orphans put to the mercy of their paternal Uncle.

Though, they were indeed luckier than most. With her brother the present Marquess of Northampton, the daughters of the late Thomas & Maud inherited their fair share of rare portraits, jewels and a fine dowry to secure a good match - but since their brother was still too young to understand what was needed for two young girls, they remained under the house of their Uncle, forever seemingly waiting to be returned to the brother, as was often foretold by their mother when sent stories though fine ink.

When Alice is called to court by the behest and control of her Uncle, she is seventeen. Pale, a fair-height and with the favourable red-hair worn by the King himself, she is quickly anointed as a beauty of Court to serve beneath Queen Anne Boleyn as a Lady in Waiting. Though, unlike perhaps many of her peers, the memory of her mother burns into her mind like a red-hot-poker, for too often it was declared that Boleyn was but a concubine, a woman unworthy of the place once warmed by a royal Princess of Aragon. With a stubborn nature, her unruliness once matched with a sincere need to get what she wanted, turns her beauty into something to be scorned - for whether it was the Queen, the other jealous ladies or deterred male courtiers, rumours well around her seventeen year old self that declare her a coquette, a liar and indeed a Pope sympathiser.

Of course, they weren't wrong.

Shunned, yet kept beneath the stern eye of the Queen and her court, by the late age of twenty-four, Alice is matched to the Viscount Beauchamp, the youngest brother to the late Seymours who had swiftly been executed for treason against the crown - a family whom Alice had kept at arm's length for both her own survival and in the hope of side-stepping their eventual demise. It was by the puppeteer hand of her Uncle, that the marriage was made, and though Alice found herself rather repelled with a marriage to a man who had not saved his own family, she is forced to go along with it - mostly, in some hope to save her reputation and head, which lingers upon the chopping block for her constant letters sent to the Lady Mary, a friendship nourished by her mother's own to Mary's mother.

But what else is there to say? For that is the biography of Alice Parr, and this is now the re-telling of Alice Seymour. Still, shunned by the noble ladies in fear of catching her reputation (which, though muted by her marriage is still questioned by the flicker of her eyelashes), Alice becomes a mother. Arthur is born, and beloved. But a maternal devotion does little to a boy meant to become his father's son, and before she returns to court there are already rumours that he is not of his father's loins but of some other courtier who had fallen for her lustful woes - even, by the gossip of chambermaids, the Prince William has found it hard to look yonder.

In an effort to secure her son's wellbeing, she begins to evoke her parents' intellect and spirit by renewing the works set upon the Seymour home of Wulfhall, which had fallen into disrepair after the fall of the late Edward, Thomas and Jane Seymour, before becoming a mother once more to a daughter, little Catherine, named after the Queen in a coy act of subterfuge.

Now, she returns to court again as a Viscountess. And, hey, if she survives this season, then there's no end to her appetite.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elizabeth Cheyne, Lady Vaux (1505-1556)

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/1498–1543, German-Swiss)

Elizabeth Vaux was born in 1509, the daughter of Sir Thomas Cheney, an Esquire of the Body to Henry VIII, and Anne Parr. She became a ward of the 1st Baron Vaux in 1516 and was married to his son Thomas (later 2nd Baron Vaux of Harrowden) before May 1523. Mother of William Vaux, 3rd Baron Vaux of Harrowden; Maud Vaux; Anne Bray and Nicholas Vaux

#dianthus#carnation#portrait#painting#Hans Holbein the Younger#women portrait#16th century painting#16th century art#Elizabeth Cheyne Lady Vaux

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Yaxley Legacy (Post-HPHM)

A/N: So, they have been bugging me for a while, so I wanted to write a little something of their relationship as kin. Eloise belongs to @kathrynalicemc whose OC I borrowed for this

Summary: Camille and Eloise start over as the only family they have left

May 20th, 1998

Camille dipped her feet on the water with the Dead Sea salt and white rose petals she had ordered her dear butler Humphry for a relaxing skincare day. So much had happened, so many lives lost, and so many deaths and devastation left in the world, yet Camille had been sheltered from it by her father, who was adamant on not losing his only heir.

Her mother, Céline, was outside with her family, and her father Charles was at Parliament trying to maintain the family’s good name. She looked at her mirror and her bright blue eyes and dark hair, like her great-great grandmother Primrose have had once, when she was her age.

It was a pity to not have lived up to her heroic ancestress, who had ridden all the way from London to Leeds to avoid Winbourne being taken by force by the Buckinghams, who hadn’t been a problem since the Second Muggle World War, an equally devastating event that left no wizard with a thirst of knowledge of the muggles indifferent. She herself descended from a muggle woman, Margaret Taylor, a woman who changed Winbourne’s routines forever. She was her great-grandfather Vincent’s second wife and his only legal wife by the viscounty. She had been a potential target to Grindelwald, but her title as Viscountess had protected her, alongside her husband’s relations to important families such as the Fersens, Brokenshires, the Yaxleys, and many others.

She dipped her strawberry on her chocolate fondue when she heard a knock and quickly cleaned her wet feet and put on slippers and went downstairs and opened the door, where a tawny-skinned girl of her age, with dark eyes and a serious face and short hair waited for her. As she spoke, realisation dawned on her: she was her cousin, Eloise Yaxley, and she had lost many things. Too many for a young girl.

When she let her in, she called for Humphry, who curtsied at her “Who is your guest, ma’am?”

“This, sir, is my cousin Eloise. Please prepare the best wine you have and prepare her rooms: she will be staying the night. If you do not have any more plans today?”

Eloise awkwardly shook her head “No. And… I’m a bit curious about this whole castle.”

Camille giggled “House or estate is fine. It is not big enough to be considered a castle.”

As they walked over the halls, they stopped on the portrait room, where all of their ancestors’ portraits were hung. Eloise eyed some, and her eye caught the oldest one, dating back to 1466. Camille smiled “That is Sancia Somerset, formerly D’Este, a famous Italian noblewoman who married into the family. Her money and influence put the family in good name with the muggle king Edward IV and would eventually lead to be named viscounts.”

Eloise frowned “Weren’t you viscounts already?”

Camille smiled calmly “At first, we were mere knights, but it was during the Tudor Era, especially the reign of Queen Catherine Parr when who would be the first Viscountess Somerset, Roselyn, who was a Cromwell, a very influent family back then, who gained her affection and trust and with her husband Thomas, who took care of the King’s most… private areas eventually gifted him the abandoned viscounty and title.”

Eloise looked curiously at Camille “What do you mean, ‘most private areas’?”

Camille looked away bashfully “There was this curious position during Henry VIII’s reign where one awarded chore was to make sure that the king relieved himself in the bathroom and that such business was disposed.”

Eloise burst laughing out loud, doubling in laughter “Are you telling me… that you got your title by wiping the king’s arse?” She laughed again “Now that’s precious!”

Camille tried her best to be serious, but eventually gave up and joined the laughter “I guess it is amusing.”

Their faces went towards the centre of the room with a Victorian portrait of a incredibly beautiful woman, with dark raven hair and deep blue eyes, full lips and barely noticeable freckles, posing with a beautiful blue tiara and a blue choker, alongside a blue ring that had a similar gemstone to Rowena Ravenclaw’s tiara and a beautiful blue gown that seemed to date to the late 1890s. “And here we have the woman who started it all, the Queen Victoria to the Yaxleys: Primrose Sabrina Yaxley, who married into the family and would end up being Minister of Magic and one of the most famous and loved women in our history, in both muggle and wizard history. She had five children with her husband, a pureblood Yaxley, and they all went on to marry interesting people who expanded the tree and family ties. She had a very interesting life and was incredibly smart, witty, heroic and had the mannerisms and poise of a queen. She was a paragon of the peerage and her wisdom and tenacity kept us from falling into oblivion. Because of her, the estate is still standing. We are related to earls, marquises, princes and many pureblood families because of her and her children.” They moved on and Eloise looked at an oddly familiar figure of the portrait of a young woman, from the 1940s who had the same dark hair and blue eyes, but with hardened features and holding a baby on her arms “And this is your grandmother, Gia Yaxley. You have many traits of her and her husband, who took her name. He was a Polish refugee of the war and met Gia through a common ancestor, Countess Alexandra Fersen, the first daughter of Primrose. As she nursed him, they fell in love. You have his skin and eyes, as well as his face features and dark hair.” She placed a hand on her shoulder “You are not your father’s daughter. You are a Yaxley, just not the kind he tried to bully you into. You are steadfast, true to yourself, brave, wise, kind, cunning and with the heart of a lion and a strong sense of character and that independence and pride that makes us who we are. That is the legacy Gia tried to teach your father. He was just too weak-minded and indoctrinated by Voldemort to listen to her.”

Eloise smiled at her and looked at the latest photo portrait: it was a man with brown hair and a 70s hairstyle and a neat suit on him, smiling. Camille smiled fondly “And that is my father, the current Viscount of Winbourne. He is the twelfth of his generation. The Yaxley name has been around for 94 years since Primrose’s marriage to Laurent Yaxley in 1904. I will be the second Viscountess Yaxley after Primrose on her own right.”

Eloise looked at the many portraits of men, women, daughters, sons and grandsons that surrounded her. Six hundred years of history in one room, told by portraits. She realised, there was so much of her family that she had been depraved of, that now she craved for more knowledge, and would certainly frequent this household; she had a family here, and would not lose them this time.

“I would like to learn more of them. All of them, actually. And of you, of course. As I said before, I want to be part of your lives.”

Camille smiled fondly “I’d love nothing more. I was taking up a skincare routine. Care to join me? We won’t do anything against your will.”

“What were you doing?”

“I was dipping my feet on Dead Sea salt and rose petals that are incredible for sore feet and was about to take a mask and cream for the face.”

Eloise smiled for once “My feet are sore… do tell me more about it.”

Camille giggled and led her to the room she had been in, where she took off her slippers and dipped on them again and beckoned Eloise to join them, where she took off her heavy boots and sighed at the fresh water and the salt and petals on her skin, eating the atrocities on her feet. She also helped herself with chocolate fondue and strawberries and listening to ABBA as the maids took off the dirt and healed the wounds that she had gained for the Phoenix Resistance as both bonded over many things.

Camille teased her on having let the war destroy her pretty face and Eloise could only imagine Rye’s face when he saw her all neat and cleaned.

After a long day, Camille gave her Gia’s bedroom that was filled with a magical album with photos taken by her. She opened it and saw a photo of a much older Primrose with a baby on her arms. Gia, she reckoned. She was smiling, though she had a bit of a nostalgic look on her face. On the next one, there was a two-year-old Gia being twirled by an elderly man, Laurent she thought. She was giggling and he was smiling wide, beaming at his daughter. Apparently, she had been a surprise baby.

The next one was a six-year-old Gia hugging her sister Alexandra, who, according to her notes, was celebrating her engagement to the Earl of Helwater. She looked beautiful, and resembled Primrose much.

Then, a photo in 1928 was made by someone else to Gia, who was in Hufflepuff robes: clearly her father’s worst nightmare: a half-blood who was also a Hufflepuff, who married a foreign muggleborn. She always knew he idolized someone else in her family, and suspected he idolized Primrose: beautiful half-blood woman who married into a pureblood family and gave many children.

The next photo was taken by someone else: it was Gia and her grandfather Ahmed, fighting off some dementors and other possible death eaters, though Eloise smirked at the obvious that Gia was doing most of the fighting.

The next photo touched her heart: it was Gia with her uncles and aunts surrounding her father Corban. She was smiling wide at him and so were her aunts and uncles. She clearly loved her father, but she wondered how things went down… he clearly never talked about her, and she now knew why: he had resented her for the heritage she left him. She had wished to meet her, but women like her never had a happy ending. She knew she had died during her stay at Hogwarts, in 1980, and that her remaining sisters and youngest children had been at her side.

Yet another reason to hate her father. She wondered if he’d get his ass whooped in hell, though someone as her Grandmother Gia had a place earned in heaven, with no more headaches from her father. She wished she could say the same.

She was afraid that Camille would kick her out when she told her what she had done during the war. She was wise and knowledgeable, she feared that what she had done was… too unforgivable.

The maid came with comfortable pyjamas and told her to ring the bell if she needed something from them and that breakfast would be served at 8.30. She’d meet her uncle and the viscount. Great… This looked like it’d be an awkward family reunion.

#hphm#the phoenix resistance#oc: camille yaxley#eloise yaxley#yaxley family#Harry Potter: Hogwarts Mystery#hogwarts mystery#mywriting*

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"By comparison with numerous ‘workshop’ versions, this rediscovered print from an apparently lost portrait of Anne Boleyn has every appearance of an authentic likeness, with its claim to represent Anne supported by Sir Roy Strong’s Tudor and Jacobean iconography and Eric Ives’s work in establishing a link between the portrait style and the gold and enamel image in the ‘Queen Elizabeth’s ring’, currently held by the Trustees of Chequers.

Two copies of the print have so far emerged – one revealing the inscription near the top: ANNA BOLINA UXOR HVIII, perhaps added at a later date, and the other, of lesser quality, showing a little more of the shadowed background to the portrait and of the sitter’s wide black sleeves.

It would not appear that the portrait is by Holbein. But in style and pose it does correspond closely to other contemporary female paintings by the German artist, Joos van Cleve, particularly his 1530 portrait of Eleanor, Queen of France (below).

[...]

It is further significant that its sitter’s features, unlike those of other ‘workshop’ copies, bear close comparison with the Holbein ‘Anne Boleyn’ drawing in the British Museum, which has been and is still disputed as a likeness. With the ‘Van Cleve’ portrait reversed and the two images set side by side, the lines of forehead, cheek and chin appear virtually identical. The long, narrow jawline – also evident in portraits of Anne’s daughter, Elizabeth, and of her Howard and Carey relatives – is accentuated in the painting by the (invisibly narrow) ribbon which holds the French crépine head-dress in place. The shapes of the nose, mouth and brows, a little flattered in the painting, are essentially similar; while something indefinable in the expression of the dark eyes establishes a common likeness.

Moreover, there are good reasons for supposing that Van Cleve had the opportunity to paint Anne Boleyn in 1532. His well attested portrait of Henry VIII has been dated for the early 1530s and it has been suggested that Van Cleve came to England for the commission. According to the Royal Collection Trust, this portrait ‘may have been painted to commemorate his visit to Calais in 1532’. In fact, it is more likely that the King sat for the artist in Calais or Boulogne during the visit itself; and it follows that a portrait of Anne Boleyn by Van Cleve could also have been undertaken while she was there with him. It is known that Van Cleve was summoned to work at the French court by François I in the early 1530s, and the 32 days Henry and Anne spent in France in the autumn of 1532 would have allowed ample time for preliminary sketches, if not for completed portraits.

The question of how a portrait of Anne Boleyn, sketched in 1532 and perhaps completed in time for her coronation in 1533, survived her disgrace and death in 1536, when other images of her were deliberately destroyed, might be explained by the fact that artists were frequently required to undertake multiple versions of royal portraits. Van Cleve was known for his ‘impressive studio organisation and collaboration’, and at least two versions of his portrait of Eleanor of France survive, wearing different costumes and jewellery.

There are also two copies of Henry VIII’s portrait by Van Cleve, both of good quality, in the Royal Collection and that of Burghley House.

If Anne Boleyn did sit for Van Cleve in Calais, one would expect official versions of the portrait to feature jewellery obtained for her from Katherine of Aragon in time for the French visit; (e.g. the jewelled cross with pendant pearl in Katherine’s miniature by Lucas Horenbout, and worn successively by Anne in her portrait medal of 1534, Queen Jane in the Whitehall Mural and by Catherine Parr in another Horenbout miniature.) Moreover, if the one surviving original portrait of Anne features a symbolically initialled ‘B’ pendant – with B being for Boleyn, rather than A for Anne – it was very possibly ordered by her father, Thomas Boleyn, for his portrait gallery at Hever, where a later copy hangs today. In similar circumstances, Edward Seymour commissioned his own portrait of his sister Jane. Nor is it hard to imagine a plausible chain of ownership for such a survival – from Thomas Boleyn’s death in 1539 – through Anna of Cleves, who gained Hever Castle and its contents as a part of her divorce settlement in 1541 – to her executor, Henry Fitzalan, who had charge of her effects on Anna’s death in 1557 – to his son-in-law, John, Baron Lumley, who inherited Fitzalan’s paintings in 1580 and included a likeness of Anne Boleyn in his inventory of 1590.

It is known that Anna of Cleves personally occupied Hever Castle and would have been familiar with its paintings. If she had decided to sell a portrait of her disgraced predecessor by her countryman, Van Cleve – as a notable art collector, her friend Henry Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel would have been an obvious buyer. Alternatively, if she’d left the painting for his disposal as her executor, he’d surely have taken the opportunity to acquire it, having known Anne Boleyn personally and accompanied her to Calais in 1532. On Henry Fitzalan’s death, his art collection was merged with that of his son-in-law and heir, John, Baron Lumley, which a decade later certainly did include a portrait of Anne Boleyn.

The fact that the portrait in the Lumley Inventory of 1590 is described as ‘full-length’ would not have made it unusual (Queens Jane Seymour and Catherine Parr were both painted full-length) or incompatible with other commissions for Joos van Cleve’s studio. We now know that the Lumley portrait was cut down at a later date; and if the rediscovered head-and-shoulders print is amalgamated with another three-quarter-length female portrait by Van Cleve (as below), some idea can be gained of how such a painting might originally have appeared."

#i loooove this one#anne boleyn#@ god drop the full length portrait reveal if you'd like to shift me from atheism. tick tock.#richard masefield

1 note

·

View note