Video

youtube

Today I’ve been hosted on the LawyerFair daily podcast, run by the great Andrew Weaver. I’ve been ranting on the connections between Music and Law for about 10 minutes. If you make it to the end you can hear me saying the word “onanistic” with a notable Italian accent. The Lawyerfair podcast hosts several legal innovators, so stay tuned, and have a look at what they do!

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Why couldn’t law be designed by designers as well? Designers, humans who love beauty and keep users in mind. All the time. Well, most of the time.

Beautiful Law: how design and visualization can make the law simpler, useful and even fascinating, on Legal Futures (Yes, I just quoted myself)

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Design, music and law: a recap

by Serena Manzoli - Get updates of new posts here

On this blog I try to bring to light all of the analogies I see between law, music and design. Again, caveat emptor, this is not a blog on music law, architecture law and boring stuff like that. I leave that to real lawyers.

Everyone has its obsessions and mine are all about finding analogies and common patterns and drawing rules from them quite arbitrarily. But that's it, I've lot of fun.

Many analogies among the flourishing worlds of music and design and the dry world of law are possible, quite unexpectedly, and so far I've been discussing some. But there are many more, and finding them is a fascinating game.

A brief recap of what I've been seeing so far:

Music

Should we teach law the way we teach music, hands on, with a more concrete method focused on real cases? (Making music, learning law) More extremely: should we learn law like self-taught musicians learn music, that is, by listening, and playing and mimicking? (I discuss that on Law and Vignelli, plus Anna Calvi)

Does history of law match history of music? That's the elegant hypothesis Bernard Holland advances here (Mining music and law for original meanings)

Design

What can design teach the law? Some things. First, that the way a legal system is made cannot overlook the society on which it's imposed. Second, that the law has been -and to a certain measure still is- a tool in the hands of people to determine their day to day relationships. I think of private law here. Third, that law is made for people and legislator should always keep it in mind (Law and Vignelli, first analogy).

Again, many other analogies are possible.

Urban design and law? For instance I'm fascinated by how a city grid resembles a network of laws and how city grids and legal networks are different from each other. This analogy brings us straight toward the network analysis of legal systems, which is a nascent and maybe promising field.

Math and music and law? But I'm fascinated also by this (Godel, Escher, Bach), and how music and mathematic could share some aspects in the end (what Pythagoras hinted at). Then maybe also mathematic and law? Which takes us to the huge experiment in counting instances that the National Archives are carrying out with the project Big Data for law. They count everything in the legal corpus to see if there's something interesting, a pattern that can be highligted for instance.

Design patterns and law? Also, are there good design practices in legislation that we can isolate and teach legal drafters so that they avoid drafting horrible, unintelligible laws? If architects and urban designers have tried to learn them, what about lawyers? That's exactly what Big Data for law is asking, and again, there's an analogy with architectural Design Patterns (one of many, the book a Pattern Language on architecture and urban design).

Patterns of music, patterns of law? Talking about patterns, I wonder if there's a way to carry out with regard to law, the excellent analysis Ethan Hein is doing on music's structures and rhythms.

Let me know if something else comes to mind, we can feature it here. Also, suggest reads.

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Pythagoras surmised that there might be a divine reason behind our tendency to find specific harmonies and note intervals more pleasant to ear than others. He pointed out that there were mathematical congruencies behind these notes (...) Pythagoras was a bit of a numbers nut, so the fact that there were mathematic underpinnings to the most common musical harmonies was very exciting for him. It was like unlocking a key to the universe.

David Byrne, on a fascinating passage of How Music Works. Which quite resonates with this blog, by the way.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Studying music, learning law

by Serena Manzoli - Get updates of new posts here

Legal tech entrepreneur Marc Lauritsen - who's also a musician - has read the post I published a couple of days ago (Bernard Holland: Mining music and law for original meaning) and pointed me to the article Studying music, learning law, by lawyer-musician Alfred C. Aman.

It provides another point of view on the links between law and music (which has nothing to do with music law, although I wrote a music law post here, I admit).

"Understanding the structure of music, its historical roots and its creative possibilities has many similarities to studying law"

says Aman.

Right! I'm happy to see that the music&law thing resonates with many.

Full article here . Read it.

The point he makes:

You can learn how to teach law by looking at music schools;

Most part of the music school curriculum is based on practice, on learning by doing;

By focusing on doing, you learn to make solutions (the current law school approach is more 'to create problems');

This hands-on approach develops creativity;

It goes on the same direction of what I wrote here, when I quoted Anna Calvi's way of playing and teaching music ("there’s a basic instinct for what sounds good and what works that can’t really be taught").

And even if the method you learn in music schools is much more theoretical from the one developed by self-taught musicians, it is still much more practical and hands-on than the ones learned in law schools.

Full article here.

---------

#marc lauritsen#alfred c. aman#studying music learning law#patterns of music and law#anna calvi#music

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bernard Holland: Mining Music and Law For Original Meanings

by Serena Manzoli - Get updates of new posts here

Stumbled upon this beautiful 1998 article by Bernard Holland on NY Times today, and cheered up. History of music and history of law share common patterns, he says. Great. Same direction of this blog!

"Music would seem an odd metaphor for the doings of lawyers and judges. Take as one example law as seen by the Enlightenment, an 18th-century system that conveyed fairness to humans by actually keeping humanity out of its processes. Classical music, an esthetic in which Mozart and Haydn participated but also rose above, came along at precisely the same time. Its passions were organized in neat musical designs, which imposed order and even grace on the disorders of life."

Full article here. Worth a read, or two. http://www.nytimes.com/1998/04/22/arts/critic-s-notebook-mining-music-and-law-for-original-meanings.html

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

"And if I have the good fortune to live on in your minds, it would be in mythological form"

Jean Cocteau speaks to the year 2000.

0 notes

Text

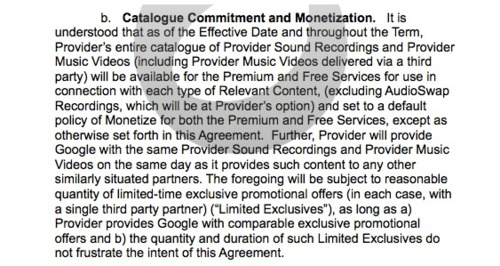

Some cold analysis of the YouTube-Indie labels story, and some long term reflections.

by Serena Manzoli - Get updates of new posts here

So what's going on with Google, YouTube and Indie labels?

There's been so much fuss, indies tearing their hair, lawyers trying to tone it down: I try to sum up the whole thing here for your delight and delectation.

Alright, this is not a music law blog. It is, however, a blog where law and music meet. So, here we go. If you don't know the ante-fact, have a read here or here.

And there's also this update that Google may be revising its position now.

Why is the contract so bad? Wait, is it really bad?

I read the contract. If you don't care about the legal aspects of the thing you'll probably get bored to read this paragraph as much as I got bored to write it. In this case, just skip to the next paragraph.

The contract is horrible under one aspect: the dull, boring, convoluted legalese, which shows its best both in syntax and in vocabulary. This whole, 32 pages long, piece of horror story is here.

Apart from this, the contract is bad for indies, yes. I'm not saying (yet) that Google is abusing its position, that the contract can't be negotiated, that it's morally bad etc. I'm saying that, if I was an indie, I wouldn't be happy to sign something like this. 4 reasons.

1: The royalties. Google is offering indies this:

Audio only music: 65.5% of the service revenue (of which, 10% to publishers and performance rights organizations).

Music videos (the main reason you go on YouTube, right?) the rate drops to 55%: 45% going to labels and 10% to publishers.

Spotify and Rdio pay an aggregate 70% according to this source and this, so slightly better than what YouTube is offering.

Is this clause bad? Abstractly yes, but then it depends on how much the revenue is: if YouTube premium works better than Spotify, then labels get the 55% of a bigger pie. YouTube has, after all, more users than Spotify or Rdio have, and probably more premium users as well.

On the other hand the risk, on the not-too-long term, is that rates will drop down in the whole music industry as a consequence, and it's very much what labels are fearing I think.

And then there's another clause:

It means: if a major agrees to a lower royalty, we'll lower your royalty as well. Now, there are two interpretations of that. According to Mick Masnick of TechDirt, the clause is fully reasonable: if the market changes, and majors need to adjust the rates, indies need to adjust the rates accordingly. Secondly, why should majors want to lower their royalties? "They're going to seek to increase them, rather than the other way around." says Masnick. It makes sense. But someone sees it differently: Guardian journalist and songwriter Helienne Lindvall said that "We’re hearing that a billion dollars has been paid by YouTube to the major labels" in advances for its new service. If it's true -we don't know- then majors will probably agree for a lower royalty, having had the payment up front. And indies will get screwed.

2: The Covenant not to sue clause.

Basically, Google asks indies never to sue them for any claim related to copyright. And this is bad, period.

3: The Catalogue commitment clause

YouTube asks indies to make all of their content available. They have a good reason for that. On the other hand, the clause it's burdensome: it limits the freedom and bargaining power of indies: what if I decide to withdraw my song from YouTube because it monetize too little, and make it available somewhere else?

4: What happen if indies fail to sign the contract?

The Guardian made an excellent exegesis of the situation before the contract was leaked, coming to 3 possible outcomes:

One: YouTube is indeed threatening to block the videos of indie labels: if they don't sign up to the terms of its new paid music service, their videos will be removed from its free service too. Although Vevo-run channels seem likely to stay up.

Two: YouTube will block indie labels from monetisation of their videos on its free service. It's possible that YouTube will leave labels' videos up, but block them from making money from ads in and around those videos – as well as from using its Content ID system to make money from ads shown on videos uploaded by YouTube users featuring their music.

Three: This is all just a big misunderstanding. If indie labels choose not to sign up for YouTube's new paid music service, their videos will be blocked on it, but left alone on the existing free service.

And after the contract got leaked, they didn't know any better. As they put it

Any information about (...) the alleged threats to block labels' channels if they didn't sign up – including whether that means remove them from YouTube entirely or simply block them from making money from advertising – was delivered outside the contract itself.

But option 3 seems very unlikely, and option 1 seems unlikely too. So, probably if you don't sign, your YouTube videos stay there, but you don't get any money from ads. Can't indies just remove them? Sure, but only by asking Google to remove videos of their music uploaded by other users. How come? Didn't you say there's a Content ID system that's able to recognize when someone else uploads a video which features your music? Sure, but apparently Google doesn't really make it work. So a label has to expressly ask YouTube to remove the infringing content. But it's time consuming and you just can't do that for every single video.

So, the contract is bad. Other bad things, apart from the legal chit-chat?

Yep, 3 bad things.

1: Abuse of dominant position. It is quite clear is that Google is bullying because it has a dominant position on the market. The problem is not that indie labels count for the 5% of the music market, although they could obtain much better conditions if they counted more themselves. The problem is that Google is virtually a monopolist. And that's also the reason why the independent music body Impala has formally filed a complaint with the European Commission in Brussels. Monopoly is never good. Not only for indies. It's bad for everyone in the market.

2: Gangsta moves. If it's true what we said above (that Google is keeping the videos on YouTube, but removing the advertising) then it means that they're basically playing in and out the legal field, crossing the line as they want. Think about it. If a label decides not to sign, and wants its content removed - also videos illegally uploaded by other users- Google can do it, but only after the label expressly asks for it: imagine doing that for every single video: it's costly and time consuming, so the videos will likely remain there.. It's not only hypocrite but it's also gangster like. Andrew Orlowski of the Register has cleverly expressed that with:

In short, the move will preserve Google's illegal supply chain by cracking down on its legal supply chain.

In short: I want to sell you my content, but you don't want to pay me what I deserve. Fuck off, then, I'm going to take it away from you. Oops, no wait. I really can't! Because you already own it, but illegally!

3: Where're trust and long term relationships? Let's go ethical now. Google is disappointing. They're bullying, showing the muscles, just as you would expect from a big corporation. They're being arrogant and dismissive.

And painfully short sighted.

Artists are disappointed. Costas Andreou, musician and sound designer, meaningfully said:

"It takes more than a legal template file and a click on a form button to develop a long lasting cultural communication. You need to be able to reach a human being at an email address and on the phone and talk. Shake their hand. Look each other in the eyes.

It is not a matter of awareness, but of choice: if companies are excited about establishing and maintaining profound relationships with artists, they know what to take care of. If they are interested in building and handling asinine machines, that is common knowledge, as well. Calling the trivial availability of a machine and its interface a relationship is not a reasonable approach."

That's very much what I think too. Business relationships are based on trust and respect. An entrepreneur can be, must be, respectful of the society in which he operates. The entrepreneur has a social role, not just an economic role. Naive? Someone else thought the same.

Moreover, music is not just a market, it's a culture. And when you talk about music you shouldn't talk about quantity but quality as well. You're not selling bolt-ons.

The production of indie labels may amount to just 5% of the market, and still, consider how rich and varied it is: and no, I'm not thinking about Adele, sorry, even if her name came out quite often in this debate (but again to testify people keep in mind much often quantity over quality).

What's going to happen next?

Impala has filed its formal complaint to the EU Commission. Frankly, I don't expect anything meaningful to come out of that.

Yesterday the FT reported that Google may want to renegotiate the terms of the agreement. It seems good.

Then there're a few questions that may have a response in a relatively short term:

Will YouTube subscription service work?

Will YouTube competitors grow stronger?

Will indies be able to get better terms, as someone said here?

But on the long term, I think that Google is having its pay-back. Music industry is a market which changes swiftly and abruptly. If Google makes the situation sub-optimal for artists (not for labels: for artists), then something will happen (a new service? a new paying system? fan bases getting more loyal?) and the market will re-adjust on a stage which is optimal for everyone. That's why their arrogance seems silly and short sighted, not only to me.

------------------------------------------------------------------

#google#youtube#indie labels#billboard#the guardian#register.co.uk#costas andreou#andrew orloski#mich masnick#tech dirt#helienne lindval#spotify#rdio#youtube vs indies#youtube vs indie labels

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wildcat Mixtape # 3: Anna Ronkainen

Music and law, remember?

I've asked some of the coolest folks in the legal tech community to make me a mixtape. Why?

Because law and music can meet each other in many ways, and that's just one. Didn't I tell you they share the same patterns?

So, the great legal tech weirdo Anna Ronkainen has made us a mixtape, with a listening guide for tech weirdos attached: it's really good!

Anna Ronkainen is Chief Scientist and co-founder at TrademarkNow, a legal technology juggernaut continuing on her never-ending doctoral research project. She secretly wishes she had kept playing the French horn.

The Legal Startup Mixtape

by Anna Ronkainen

1. Business practices in law are outdated, everyone knows that, right? But will they ever change? After all, this poignant critique courtesy of Franz Schubert and Eduard von Rustenfeld predates Richard Susskind and the like by almost two centuries.

2. Enter the Disruptor. Sharpen your elbows and you’re good to go!

3. There will be ups...

4. ...and downs (these tracks show a healthy ratio)...

5. ...and you’ll inevitably learn a lot. The sooner you realize you don’t know everything, the better. #productmarketfit

6. The end result may not be what you had expected, but it can still be good. And in the end, it’s really all about the community.

Caveat: Some of these folks music tastes are terrible, but I let them free to play what they want. But they absolutely must stick to no Eros Ramazzotti.

Want to make me a mixtape? Let me see if you're cool enough and drop me an e-mail [email protected]

#music#music law#wildcat mixtape#anna ronkainen#trademark now#schubert#the beautiful south#beethoven#saint etienne#eva dahlgren#schoenberg

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wildcat, made short

And sweet.

Wildcat will be a legal database on UK legislation, made for humans who are not lawyers. A project to empower artists, musicians, creatives, freelancers. They need to know the law, but they don't know how to look for the law. They don't have a lawyer's shaped brain (luckily). The database will be free. Law must be free. Sign up here!

On the other hand, the Wildcat blog (you are there!) is a place to discuss on music, art and law. A kind of high level - abstract discussion. I'm so sure there are links between law, music, art and language. I'm so sure they follow the same patterns. I'm so sure if we discover these patterns we can build something new, take the law towards new directions, untangle it from the byzantine riddle it became. It's my journey, I don't know where it'll take me, but if you're smart and felt something similar, you're warmly invited to contribute, here.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Law is deadly boring, that's not a big mystery.

I always wondered, though, if there's a way to turn it into something intellectually fascinating or even fun.

Cambridge PhD candidate Julia Powles and illustrator Ilias Kyriazis have been doing the same.

They created Law Comics.

Expect to be dragged into a legal story as hectically as Lewis Carrol would do.

Alice in Patentland, the first full installment, here.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gabriele d'Annunzio, Cabiria

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wildcat mixtape #2

So if you've been following this blog for a while you know that:

The Wildcat is a legal database made for humans who are not lawyers. Humans don't know how to look for legal information: we're going to help them find what they need, for free. To empower them. Beta is getting ready and you can sign up here. We are especially focusing on artists, musicians, freelancers: this kind of humans, yes.

On the Wildcat blog, on the other hand, I'm going to develop a much more philosophical discourse on the similarity among music and law. Where it's gonna take me, I don't know.

Music is a huge form of communication, that's my leit motive, I know.

That's probably the reason why we used to make mixtapes to hit on someone.

Alright, music shares things with language (they both communicate). But what about law?

I don't demand to find an answer now, I'm just copy-pasting a playlist. But I'm sure that if you juxtapose law and music, you look for superficial and deeper connections, you make them sleep together, something will come out sooner or later. No rush.

So, the Wildcat, the legal fluffy animal, makes mixtapes (this is the one from last month). This month, it will be fresh and young. It's summer. Courtesy of

The the, Sufjan Stevens, The Magnetic Fields, Love, Tennis, The Jesus and Mary Chain, Django Django, Nancy Sinatra & Lee Hazlewood, The Knife.

Curious about all this, but you don't know what to say? Make me a mixtape.

#music#law#wildcat#wildcatplaylist#the the#sufjan stevens#django django#tennis#the jesus and mary chain#nancy sinatra#lee hazlewood#the knife#the magnetic fields#love#music law#entertainment law

0 notes

Text

Law and Vignelli, plus Anna Calvi: more analogies on design and legal systems

by Serena Manzoli - Get updates of new posts here

The Vignelli canon.

(first series of analogies, between law and the NY map, here)

In 2012 designer Massimo Vignelli knew enough about himself and his art to write a short book aimed at young designers, "with the hope of improving their design skills". That was the Canon, a short, powerful piece of literature. A fascinating philosophical read.

Vignelli divided the Canon into two parts, the Intangibles and the Tangibles.

Intangibles: these are the principles which should inspire designers' work: Intellectual elegance, Visual power, Equity, Timelessness etc.

Tangibles: the tangibles are more detailed, down to earth, guidelines: grid, paper sizes, typefaces and so on. Even here, Vignelli never goes too much into detail.

I read the Vignelli's Canon in a day. Being made of rules, you would expect a bored lawyer like me to fall asleep after a few pages. Quite the contrary. The thing is, the Canon is a beautiful read.

It's a read on principles, not on rules.

The Canon tells you where to go, but doesn't bother telling you how, why and when. It leaves you free while setting the main direction. And I think it is like that because it is a distilled of years of practice, not of theoretical speculations.

A little diversion now.

I was reading about Anna Calvi, who is, like the majority of non classical musicians, self taught.

"How did you find teaching students the guitar given that you were self-taught?"

"I wasn’t really that good at it [laughs]. I didn’t have lessons so I found it kind of hard to tell people how to do it, really. It does make you realise that certain things can be learned but there’s a basic instinct for what sounds good and what works that can’t really be taught."

(from the Escapism of Anna Calvi, Spook Magazine)

Like native speakers, self taught musicians know little or nothing about grammar of music while they're still able to compose beautifully complicated pieces. They learn by practicing, by listening and with a innate instinct for what is good and what is not.

Back to Vignelli now.

The old guy set the principles, not the rules. Exactly as any self taught musician, as any writer, he learned along the years what to do and what to avoid and toward the end he was able to distill his practice into principles, broad, large principles: but not into rules. It would have been impossible and useless to set the rules for making good design. First, because they're partially time and context dependent and secondly because...they can't be known in advance. There’s a basic instinct for what sounds good and what works that can’t really be taught.

Now the analogy. Short and sweet.

Wouldn't be great to do the same for have a legal system which sets the guidelines without bothering with all the details?

Is there a basic instinct for good and bad which doesn't need to be taught? We just sense it, and that's it. But if we try to put it into rules we just become clumsy and rigid. Can we curtail all the rules, and just focus on principles and good practices? I don't know.

p.s. I was also wondering how canon, which comes from the Greek and means law, rule, came to mean also, in music, a contrapuntal composition. I'm not sure of what this means.

However, I know that language, being a natural product of some kind of mass intelligence, helps bear connections between things. Connections between laws and music, remember? I'm so sure there's so much to explore there.

#law#vignelli#wildcat#music#canon#anna calvi#tangibles intangibles#music law#entertainment law#open law#legaldesign#legalarchitecture

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Law and Vignelli, first analogy

by Serena Manzoli - Get updates of new posts here

Great designer Massimo Vignelli passed away a couple of weeks ago. An expected outburst of cleverly written obituaries has followed.

They provided food for thought for a couple of posts, not too clever I admit, on links between law and design. This is the first.

The NY subway map.

Everyone cited the well known map of the NY subway, for which Vignelli was equally venerated and criticized. The complete story of that map is here, in an excellent piece by Paul Goldenberger. The short story is that the map designed by Vignelli was iconic, beautiful and minimal.

"Out with the complicated tangle of geographically accurate train routes. No more messy angles. Instead, train lines would run at 45 and 90 angles only. Each line was represented by a color. Each stop represented by a dot. What could be simpler?"

And Vignelli's map was so beautiful and minimal that New Yorkers hated it. Why? Apparently the map didn't respect the relative position of the stations, nor the proportions of the real city. If you wonder what it can entail, Michael Bierut articulates more on this.

"What if, for whatever reason, you wanted to get out at 59th Street and take a walk on a crisp fall evening? Imagine your surprise when you found yourself hiking for hours on a route that looked like it would take minutes on Vignelli's map."

Right, but then why people in, say, London, never complained about the Henry Beck subway map, which is as minimal as the one drafted by Vignelli?

I frankly don't know, but Bierut has an answer: London streets are so tangled, that the subway map, although disrespectful of relative distances, comes in handy to navigate it. Whereas, in NY, "Vignelli's system logical system came into conflict with another, equally logical system", the orthogonal grid of streets and avenues which evenly divides the city. New Yorkers could only be disappointed and confused by another geometric grid overimposed on the "orderly geometric grid of their streets".

Never mind that Vignelli's map was clearly much better than all the maps which came before, and you can see for yourself here.

First analogy

This made me think about law and legal systems. Laws can never function separately from the society on which they are imposed. They work well if they make life simpler; they are not to be enacted if society goes on perfectly well without them. This is true also of legal architecture. Codes worked well for some time at least in XIX century continental Europe. They wouldn't work in English Common law system, as they are clearly outdated to cope with XXI century continental Europe as well.

Second analogy

Trying to explain the Vignelli NY subway map Alice Rawsthorn said

"Here, the two maps illustrate the complexity of design’s relationship to the truth. In principle, we cannot be expected to trust anything that is not truthful, yet many of the greatest design feats have set out to deceive us, albeit for good reason. Just as the symbols and characters on your computer screen were designed to disguise the unfathomable mathematical coding of its programs, designers have devised maps to help us to make sense of befuddling terrain or transport networks. Londoners are willing to suspend disbelief when they see Beck’s “diagram,” because it is in their interest to accept its inaccuracies as expedient design ploys, while the New Yorkers who attacked Mr. Vignelli’s map felt deeply skeptical about it. Why would anyone want to redesign such an easily navigable city?"

That is, maps are simplifications that help us make sense of the reality, although we're always aware they are simplifications (like we know that a stylized design is not the real thing). Law is simplification as well, in the measure it is abstraction. We know that two cases differ in details but we feel should be treated equally, or we feel they should not. The measure of abstraction should always keep society and culture in consideration. Never too abstract, never too detailed. That's not an easy thing, like it's not easy to write good pop music, good literature and make good design. All these things are good when they resonate with people. Same must be true for the law.

Third analogy

But in the end, why do people use a subway map to navigate the city in the first place, when a subway map is meant for the subway?

Well, I do it all the time. I carry the tiny London tube map (no, I don't have a smartphone), and get lost, realize why I got lost (it takes me some time), then blame myself for using the tube map as a real map. And then I keep on doing it. You can't blame it on people if they use something the way you didn't expect they could.

Bierut said "As designers, we often fail to understand how people will actually use our work."

And this is true for laws too. People use design, as they use laws, which are design tools for society. People come first, design and coherence come second. This makes me think of the Italian system (sorry, I’m Italian), where some years ago the Courts denied the validity of the lease back agreement, a totally new figure for our legal system, only because it didn’t respect the internal coherence of the Civil Code (drafted, hey, in 1942)- where, to have a valid agreeement, you must always have a cause (consideration), and that cause must be pre-determined by the legislator.

But what if people already entered lease back agreements? How could you deny the reality of that? Silly and pretentious, isn’t it, to say they were not valid, just because they didn’t fit a frame of mind of 60 years before.

Law is a product for the users. The users should always come first.

--------------

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

An introduction to Wildcat

by Serena Manzoli - Get updates of new posts here

Caveat: this is a 5 minutes read. I wish I could have written a much shorter marketing-like post to launch this new project, but I couldn't. Oh well, if you really want something shorter, look at this. If you want a full theoretical explanation of what Wildcat is going to be, hold on instead.

First thing first:

Wildcat is my second legal tech project. A project to make the law closer to the people. A legal database made for people, not lawyers.

And now the background.

When I studied law (in Italy it takes 5 years now, 5 looong years which look very much alike) I learned two things.

First, I learned to think like a lawyer. I like to repeat it: lawyers don't think like you. They don't only learn legal concepts and legal terms which you are not aware of. They learn a brand-new frame of mind, they are dragged in a totally new world (kind of a dry one). You are able to see things through the lawyer's lenses from now on. That is: you look at a car accident and think: that's a tort. You argue with your landlord and think in terms of 'I have the right to' rather than 'I want to', 'I ask you to'. Enthusiastic friends come to you to talk about their new projects and you dampen them saying that some things are not allowed under the law.

Second, I learned that law was, in the end, damnly boring. No Cicero, no Perry Mason, no passionate closing statements there. Just boredom. There's a part of boredom in every thing you study I guess, at least when you study it the continental way, trying to squeeze concepts in your head, rather than working with them. But studying law, oh god.

The same two aspects that I learned so well, frame of mind and boredom, contribute a good deal to alienate the law from the people.

There would be a good deal to tell here, but let's go back to Wildcat.

Humans, not lawyers, look for legal information. They do it on the internet too, and they use public legal databases as legislation.gov.uk.

When they are on legal databases, they don't always find what they need. One of the reasons is that they don't know what to look for and how to do it. They have a problem, a very concrete one: but they can't just do as they were on google. They can't type "can I plant a tree in my garden?" or "how do I license my pictures to a client?". They need to frame it using legal words and legal concepts, which is not easy and not obvious for someone who doesn't think like a lawyer.

This is an issue I hope to overcome with Wildcat: a legal database for humans, not lawyers.

To see how it looks like, you need to wait for the beta to get ready. For now I can tell you I'm going start from the UK and I'm going to address normal people, especially freelancers, creatives, musicians. The reason why (apart from the marketing strategy bla bla) will appear clear as you keep reading.

So let's come to the second issue: people perceive law and lawyers as something boring: the less they deal with them the happier they are. They're not to blame. I wonder if there's a way to make the law more enjoyable, like it was music, like it was literature, like it was cinema.

I'm sure there are some common patterns that law and music share (John Sheridan, btw, thinks the same). To understand these patterns and to make the law more fascinating will be the target of the Wildcat blog.

This is much more challenging. I guess you will excuse me if the posts will look random in their immature attempt to connect law to music, to art, to cinema, or at least to the intellectual fascination of brain teasers and paradoxes.

I know there's a way to make law interesting, to make it charming, to make it beautiful, and to bring it back to people in a natural way. Help me find it.

---------

#wildcat#introduction#legal tech#legal innovation#legal startup#serena manzoli#music law art#hot#john sheridan#legal design#legal architecture

7 notes

·

View notes