#profane

Text

Hello! Here's my cover for #boomstudios #Profane #1 by #PeterMilligan and #RaülFernandez @raulfdez.bsky.social "Create an Arthouse Thriller at BOOM! Studios BANG!" - Revisiting old noir icons thanks to @writeneski.bsky.social !!

175 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The illusory paradise that represented a total denial of earthly life is no longer projected into the heavens, it is embedded in earthly life itself.

Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle

#reality#virtual#profane#sacred#world#paradise#spectacle#life#quotes#Debord#Guy Debord#Society of the Spectacle

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

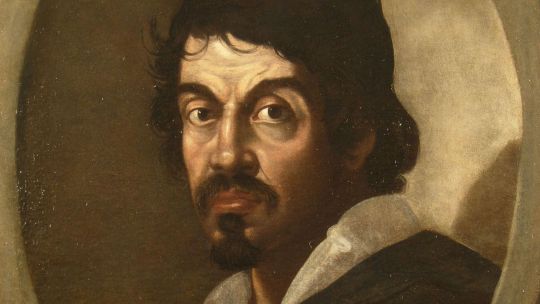

If Caravaggio were alive today today, he would have loved the cinema; his paintings take a cinematic approach. We filmmakers became aware of his work in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and he certainly was an influence on us. The best part for us was that in many cases he painted religious subject-matter but the models were obviously people from the streets; he had prostitutes playing saints. There’s something in Caravaggio that shows a real street knowledge of the sinner; his sacred paintings are profane.

Martin Scorsese on Caravaggio

Michelangelo Merisi, known to most of us as “Caravaggio,” was born on September 29, 1571 in Milan, Italy, to parents who were from the small town of Caravaggio. In the span of his 38 years long life he revolutionised painting with innovations like a unique use of chiaroscuro - with dark shadows contrasting with dramatic areas of light - and a deep sense of realism that later inspired the Baroque movement. But most of all, he developed such an iconic style that most of us can probably look at a painting and know if it’s a Caravaggio, or Caravaggio-inspired.

Merisi spent the first few years of his life in Milan, studying painting, and later moved to Rome, where his early talent impressed Cardinal Del Monte, who introduced the young painter to other high-profile Catholic figures who became commissioners of some of Caravaggio’s best work. It seemed there was no end to the artist’s creative genius. Caravaggio, much to his patron’s delight, would pump out one masterpiece after another. It seemed the more out of control his personal life became (cheating, brawling and murder were standard fare), the more his art would become more refined, more potent.

In the long list of masterpieces he left behind, both secular and religious works stand out. But it is perhaps in his religious works that the artistic transition of the master is more evident. Caravaggio is, in fact, known to have changed his style after harsh personal life experiences led him to reassess his outlook on life.

In May of 1606 Caravaggio took part in a deadly brawl in Rome and was charged with murder. He fled to Malta, in search of asylum from the Order of Saint John, a Catholic order dedicated to helping the sick and the poor. The order commissioned some of the most important late life works of the Milanese artist.

It is in these works that we notice the shift in Caravaggio’s art, from a strong focus on aesthetics to an interest in the spirituality of his subjects, which critics believe was motivated by his own introspection.

On the streets surrounding the churches and palaces, brawls and sword fights were regular occurrences. In the course of this desperate life Caravaggio created the most dramatic paintings of his age, using ordinary men and women - often prostitutes and the very poor - to model for his depictions of classic religious scenes.

By representing biblical characters in a naturalistic fashion, typically through signs of aging and poverty, Caravaggio's populist modernisation of religious parables were little short of trailblazing. Although not without his critics within the church, by effectively humanising the divine, Caravaggio made Christianity more relevant to the ordinary viewer.

For some, though, his art was too real. Bare shoulders, plunging necklines, severed heads; this raw humanity didn’t always fly in 17th century Rome. As a result, many of his pieces were rejected as altar pieces and as church hangings. One such piece, the Madonna of Loretto (now hanging in a church in Rome) was widely criticised upon its unveiling. The people of the day were shocked to behold the Mother of God leaning nonchalantly against a wall in her bare feet while holding baby Jesus in her arms.

It is ironic that the very art that today we consider “classical” and “iconic” to the Catholic faith was considered questionable and perhaps void of modesty and virtue. Yet, the fact remains that no individual artist has made such a lasting impression on the world of modern art. Truly, many have called Caravaggio the “first modern artist”. It is no surprise, then, that his style has sparked both widespread admiration and imitation throughout the centuries.

Before Pope John Paul II refined a theology of the body beautiful, Caravaggio's paintings suggested a reverence for the inherent beauty of human form.

Troubled though he may have been, his art speaks eloquently of the dignity of the mundane. Though the original medium may be weathered and cracked, the message of beauty still echoes down the centuries. And this same beauty still fuels, escapes and reduces artists to relentless seekers as surely and as forcefully as it did in Caravaggio's life.

#scorsese#martin scorsese#quote#art#artist#caravaggio#art history#aesthetics#modern#sacred#profane#rome#catholic church#christian#beauty#realism#art of the mundane

400 notes

·

View notes

Text

A whole volume could well be written on the myths of modern man, on the mythologies camouflaged in the plays that he enjoys, in the books that he reads. The cinema, that "dream factory," takes over and employs countless mythical motifs—the fight between hero and monster, initiatory combats and ordeals, paradigmatic figures and images (the maiden, the hero, the paradisal landscape, hell, and so on). Even reading includes a mythological function, not only because it replaces the recitation of myths in archaic societies and the oral literature that still lives in the rural communities of Europe, but particularly because, through reading, the modern man succeeds in obtaining an "escape from time" comparable to the "emergence from time" effected by myths. Whether modern man "kills" time with a detective story or enters such a foreign temporal universe as is represented by any novel, reading projects him out of his personal duration and incorporates him into other rhythms, makes him live in another "history."

Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and The Profane: The Nature of Religion

#quote#Mircea Eliade#Eliade#reading#cinema#film#art#books#religion#anthropology#culture#The Sacred and The Profane#sacred#profane#mythology#myth#time

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

195 notes

·

View notes

Text

Profane #1 by Peter Milligan, Raül Fernandez and Giada Marchisio. Cover by Javier Rodriguez. Variant covers by (2) Mike Deodato Jr. & Jão Canola and (3) Marguerite Sauvage. Out in June.

"Solving murders in Los Angeles is the daily bread of private detective Will Profane, but something is strange about his latest case.

When every clue points toward a famous detective novelist at the center of this mystery, Will's world will transform into something truly unreal.

Discover a new mind-bending thriller from legendary writer Peter Milligan (Hellblazer, X-Statix, Shade, The Changing Man) and veteran artist Raül Fernandez (Detective Comics, Justice League Dark) about the precariously thin line between reality and fiction - perfect for fans of BANG! and Newburn."

#profane#will profane#boom studios#peter milligan#raül fernandez#giada marchisio#javier rodriguez#mike deodato jr.#jão canola#marguerite sauvage#variant cover#comics

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Project Gamma

"We are, the both of us, profane things. We shouldn't exist. It's not fair, and it's not our fault, but . . . at least there's an us, and maybe that makes it a little more bearable."

- Llambde Fyr to his brother Gamma

TesFest23, Day 7 - Profane or In Bloom

@tes-summer-fest

#the elder scrolls#tesfest23#elf#llambde fyr#dark elf#snow elf#high elf#profane#my art#my oc#project gamma#gamma

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Profane #1 (BOOM! Studios, June 2024) variant cover by Marguerite Sauvage

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

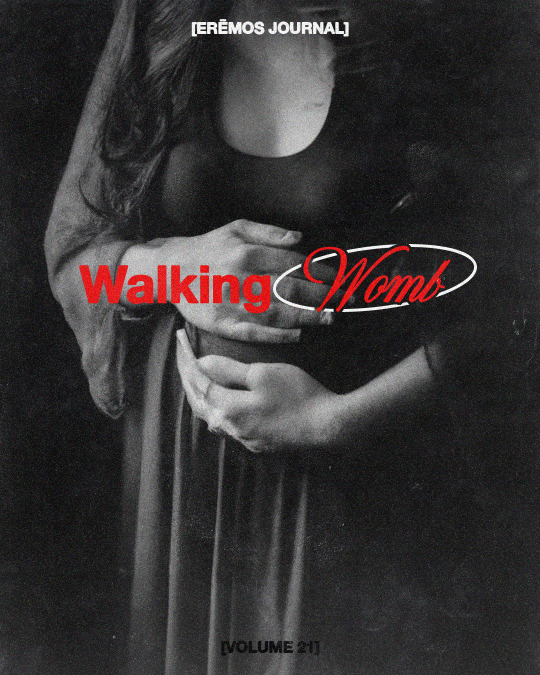

walking womb

an anonymous contribution

“We must now focus our meditation on virginity and motherhood as two particular dimensions of the fulfillment of the female personality… in conceiving and giving birth to a child, the woman ‘discovers herself through a sincere gift of self’". -Mulieris Dignitatum

I reread Mulieris Dignitatem recently, Pope John Paull II’s Apostolic Letter on the “Dignity and Vocation of Women” and it left me seething with anger.

I am 32 years old. I am not new to this world. I’ve been discovering who I am for decades. I’m a strong, confident person. I love my hobbies: reading, knitting and baking. I enjoy deep conversations with my friends and strong cups of coffee. Fall and winter are my favorite. Set a jar of pickles down in front of me and it will be gone in minutes. I love to explore the world, try new things, and host social events. I am not a stranger to myself.

And yet, here I am, 21 weeks pregnant and according to the Catholic Church, I haven’t even begun to “discover myself.” According to men I’ve never met, I was a previously unfulfilled being. These parts of myself I’ve shared with others throughout my life weren’t gift enough.

And here’s the rub: as my pregnancy progresses, I actually understand myself less. My body feels more and more foreign to me. People are no longer interested in me as an individual with hopes and dreams and passions. Instead, I am a vessel–a walking womb– who must not be interested in anything beyond the life I am growing. I feel myself disappearing in the eyes of others. And suddenly my body is now a socially acceptable topic of conversation. “How are you feeling?” “You’re getting bigger!” “Ahh I can finally see a bump!” “Can I touch your belly?” I can’t help but wonder, will I simply continue to disappear? Will I only exist as this child’s mother? How is it that the fruit of my womb is treated as sacred but the person carrying, loving, and protecting it doesn’t seem to matter?

Is this the point the Church is trying to make? By becoming less familiar with myself, I am more capable of sacrificing myself for others and therefore a better Christian? Well, disrespectfully, I refuse to make myself small just because the Church tells me to. I know I will be doing my children a disservice by not holding sacred those things that make me, me. Becoming pregnant has not made me into a more sacred, more worthy person. I have always been worthy and will continue to be worthy. Nothing I have done or will do can change that.

#deconstruction#exvangelical#deconvert#ex catholic#excatholic#exchristian#post christian#ex christian#catholic#post catholic#profane#profanity

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bringing Ashe Vernon's Profane back because it needs to have a fic based on it!!!

DON'T MAKE ME DO IT MYSELF!!!

#personal#a glimpse into mantha's life#ashe vernon#profane#poetry#someone write it#mckirk#leonard mccoy#leonard bones mccoy x reader#beetlejuice#beetlejuice x reader#star trek aos#lucifer#tom ellis#lucifer x reader#angel x demon#💜💚#fanfic gods shi#ne down upon me!

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vermis Fabula- Felipe Froeder

#afterlife#macabre#death#mystical#supernatural#dark art#sacred#souls#consciousness#spiritual#celestial#cosmic#cosmos#altered state of mind#awareness#clarity#manifestations#profane#beauty#beautiful#escape#pretty#art#dark#6#skull art#skulls#divine#tears#rebirth

123 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The true God mimics the universe, the very region he has invaded: he takes on the likeness of sticks and trees and beer cans in gutters — he presumes to be trash discarded, debris no longer noticed. Lurking, the true God literally ambushes reality and us as well. God, in very truth, attacks and injures us, in his role as antidote.

Philip K. Dick, VALIS

170 notes

·

View notes

Text

Replaying Dragon Age II: Legacy right now, and a few things are jumping out at me.

First, the note you find about how the Deep Roads were shaped by the early Wardens as well as by the dwarves, and second, that you find more Profane (what appear to be rock wraiths) inside the Warden prison.

I've thought for some time now that the primeval thaig is probably a corrupted titan and that whole "feasting upon the gods" bit in the deeply haunting "Profane" codex entry was about dwarves trapped within a dying titan consuming red lyrium in an attempt to survive, and that this maybe gave rise to the red Profane we see there.

And I mean the Profane could have just wandered into the Warden prison and become trapped there like the darkspawn, but since they're a fairly unique enemy we don't see very often even in the Deep Roads, it's fun to speculate, right. 😉

The Grey Wardens guard their secrets closely, even from their own ranks. I wonder if some very high-ranking Wardens have known about the titans all long--their corruption, the Profane, maybe even red lyrium. Who knows!

If indeed we get to go to Weisshaupt in DA:D, maybe we'll get to uncover some long-hidden Warden secrets.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Favorite word.

Profane.

Not sure why I like the sound of it so much but definitely one of my all time favorite words.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

“However, in what may be a truly occult and hidden sub-current of mystical theory and practice are mysticisms of radical Embodiment, anti-extasis. Mysticisms which reject the flight of the soul to some ‘eternal unity’. The dejection of the physicality as somehow lesser-than and the search for the Absolute elsewhere, anywhere, other than the pure corporality of flesh, muscle, and bone.

One of the most radical articulations of such a mystical encounter with the Absolute through pure embodiment was articulated by one of the greatest writers of the twentieth century, Yukio Mishima. In his 1968 essay, Sun & Steel (Taiyō to Tetsu), Mishima would expound on this encounter with the Absolute through the careful cultivation of his physical body through weight lifting, its fruition in the tragic ideal of communal, erotic suffering, and the necessity of death as the culmination of the height of this aesthetic, mystical experience.

Of course, viewing his own essay in light of his death through ritual suicide following a failed coup attempt only two years after the publication of the essay only further deepens and reveals its profound gravity as a statement of Mishima’s commitments to those very ideals. Ideals which remain controversial, even shocking, today, over fifty years later.

(…)

Sun & Steel is a work of mysticism I would argue. A mysticism very nearly unique in the history of mysticism itself. A mysticism which not only rejects words and thoughts (which many mysticisms do. That’s just apophatic mysticism), but it’s what he embraces. It’s one that embraces radical physicality as cultivated by tremendous focus on the cultivation of the muscular physique. It’s a true mysticism of flesh.

Mishima’s experience in the upper air, while profoundly recorded in Sun & Steel, were clearly…clearly not enough for him, however. Even such a limit experience was not and could not be the culmination of pure Solar embodiment. Mishima transformed himself into a work of art, his physical body became a work of art, and like all works of art they must be curated to be properly exhibited and thus appreciated. But this work of art was to prove truly ephemeral because, remember, on Mishima’s reasoning it must come to its aesthetic apex precisely in annihilation.

Like many others, I suspect that Mishima’s attempted coup with members of his militia, the Tatenokai or Shield Society, was him simply and very finely curating that very annihilation, that heroic death that he had searched out. Thus, sun and night, steel and words, culminated in a final day whereby Yukio Mishima, having neatly concluded the Nocturnal words of his Sea of Fertility tetralogy, transformed himself into a Solar, headless god and a Cephalus. That despite the sounds of jeering soldiers and, frankly, botched attempt at seppuku. Reality just always impedes upon even the most careful curation in the end.

As I said, Mishima’s Sun & Steel is a fascinating and, frankly, at times terrifying glimpse into not only the development of one of the most important literary figures of the twentieth century, but also an insight into a radical, self-described anti-Platonic mysticism, whereby the Absolute is experienced precisely and only through the development of Embodiment and not just through Embodiment, but the deliberate cultivation of the Embodiment through years of difficult and painful training, only to have it culminate in its intentional annihilation as pure aesthesis.

Now, I’m certainly not arguing that we should in any way emulate Mishima, but as he is appreciated in the world of literature, I think Sun & Steel must come to be appreciated equally as a work of philosophy and as a work of mysticism. In fact, a work of mysticism that has very little in the way of parallels. And in that way, it’s certainly worthy of attention by scholars and practitioners of mysticism.”

“The opposition between the categories of sacred and profane shapes Bataille’s thought, and in his treatment of any subject, associations are readily found that link each new pair to these constellations of sacred and profane things.

The reason Bataille’s philosophy is only ever almost systematic is that while some of the binary pairs he thinks about seem to stand fast, each part of the pair remaining perfectly distinct from its opposite, there are other pairs in which the two parts appear to fuse together, switch places, or flicker in and out of one another.

Contradictory meetings and simultaneities pervade Bataille’s work, apparently irreconcilable ideas are rendered indistinguishable; death and birth become one and the same, the life-giving sun becomes an outpouring of effluence, and rampant growth becomes explosive destruction.

The sacred is, loosely speaking, the realm of things that approach the impossible. It consists of extremity, rapture, and experiences that strain at the boundaries of human consciousness, even momentarily stretching beyond them. Inner Experience ties this world of near-impossible experiences to the mystical tradition: the accounts of religious experiences that defy ordinary categorization and description – that evade assimilation into the profane world of the everyday (Bataille places particular emphasis on the writings of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite).

For Bataille, the mystical experience aspires towards an impossible state: identification with ‘everything’. For the Christian mystic this ‘everything’ is God, but the aspiration is impossible, Bataille writes: ‘We have in fact only two certainties in this world-that we are not everything and that we will die.’ (Inner Experience, 1943)

Here, however, a characteristic twisting together of opposites occurs. Though Bataille links this impossible continuity with the ‘entirety of being’ to the sacred, he describes another kind of mystical experience that results when we recognize the impossibility of our desire for continuity at the same time as we acknowledge our mortality. This experience diverges the mystical tradition, which Bataille begins Inner Experience by critiquing, in that it is not ‘confessional’: it does not lay claim to being an experience of something, or of God, but rather to pure experience, alive, where the sentence ‘I saw God’ is deadening.

(…)

The resultant experience, that which attends the realization the impossibility of continuity with all the world, is discontinuous (that is, personal, or ‘inner’), but is nonetheless communicable. The experience of necessary discontinuity tends, paradoxically, back towards continuity, in its state of simultaneous extremes: despair and rapture.

(…)

The titles Bataille gave to his three works are appropriate to the paradoxical (or ‘impossible’) structure of his thought: Inner Experience (1943), Guilty (1944), and On Nietzsche (1945) – the Summa Atheologica (La Somme athéologique). The relation of these three texts to religion remain ambivalent throughout, and the apparent opposition between their title’s referent (Thomas Aquinas’s Summa Theologica [1485]) and their atheism never resolves itself into a straightforward distinction.

Bataille is both dismissive of and fascinated by religion. He frequently treats Christian dogma as laughable and pernicious, while returning compulsively to depictions of religious ecstasy, mystical tracts, and the ritualized sacrifices common to both modern and ancient religions.

Bataille shares with Nietzsche this decidedly theological approach to atheism, which is at least as concerned with the generation of new rituals and deities as with the dismissal of old ones. Religion is, after all, counted among Bataille’s principle modes of ecstatic expenditure. Bataille describes its proximity to death and eros; its capacity to produce moments of bliss approaching the impossible, and to make believers forget their profane, quotidian lives of material accumulation. Religion, therefore, is an object of contradictions, dual impulses straining in opposite directions.

(…)

For Bataille, the death of Christ is only a partial sacrifice, insofar as God survives and recuperates the demise of Christ’s body. This recuperation, for Bataille, is essentially profane in character, and thwarts the sacred expenditure of the sacrifice proper. The immortality of God, and Christ’s resurrection, exemplifies for Bataille the underlying profanity of Christianity (and religion at large): its reliance on the crutch of postponement and recuperation in heaven – it sullies the ecstatic expenditure of the sacrifice by expecting to get something back.

(…)

In particular, and this is a motif that recurs in almost every work Bataille ever wrote, Bataille saw the sacrifice in its various forms as the most exemplary sacred thing: an event mingling death, eros, spectacular waste, and bridging the gulf between the private selves of its spectators. Where profane life cannot tolerate the logic of the sacrifice, preferring to always invest resources and life profitably, to postpone consumption in favour of productive growth, the sacrifice expends life, food, and precious resources unproductively, now.

Bataille identifies consciousness with discontinuity. By inhabiting one’s own conscious mind, one is cut off from other minds: the precise conditions of life are those of discontinuity with others. Conscious human life is defined by the boundaries that separate self from other. Before and after life, however, continuity reigns. Both before birth and at the moment of death, these boundaries dissolve.

Bataille identifies a universal nostalgia for continuity, a hunger sated in moments of expenditure, mystical bliss, and erotic throes. The hunger for continuity approaches the desire for death, but is staved off from this target by the fear of losing one’s discontinuous self forever, requiring proxies for the experience of continuity, which nonetheless always tends towards the grave.

Chief among these, the sacrifice allows a moment of nearness to the continuity of death, without having to undergo its irremediable operation. For the sacrificed person or object, meanwhile, the sacrifice is an elevation to the domain of sacred things.

Bataille writes at length in The Accursed Share about the structure and purpose of Aztec sacrifices, dedicating an entire chapter to this phenomenon. He identifies the purpose of the Aztec sacrifice as being one of restoration: the sacrifice renders sacred again something or someone that has been made profane – has slipped into the logic of utility, production, and function. Thus, the sacrifice of slaves was deemed a restoration of the human to the world of sacred things, where the living being had been transformed into a tool of production.”

#mishima#yukio mishima#esoterica#justin sledge#mysticism#philosophy#sun & steel#seppuku#suicide#annihilation#flesh#bataille#georges bataille#sacrifice#sacred#profane#acephale#acéphale

13 notes

·

View notes