Text

Ubehebe Crater

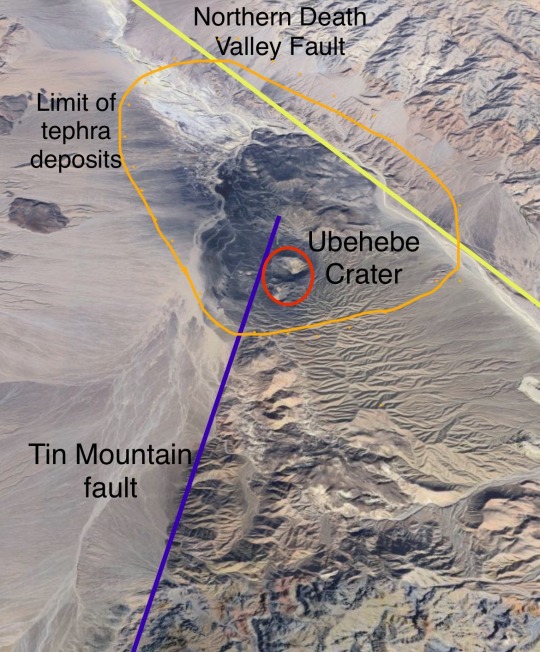

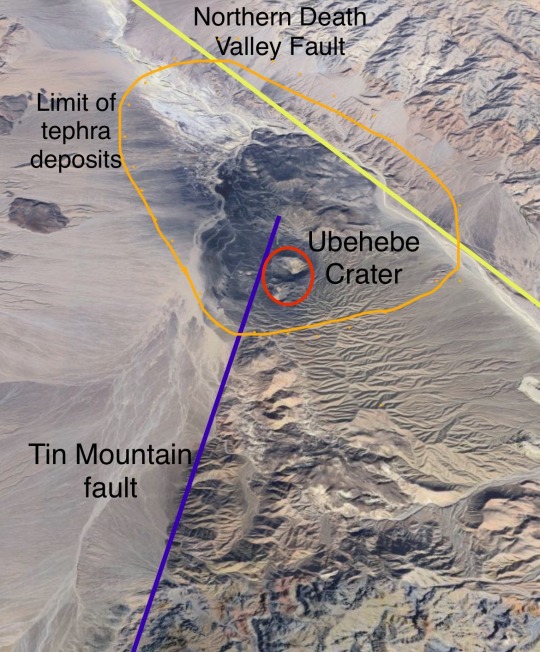

At the north end of Death Valley sits a small volcanic field. About 2,100 years ago, a body of basaltic magma forced its way to the surface along the Tin Mountain Fault, reaching the surface near the floor of Death Valley.

2,100 years ago, Death Valley was a different place. It more closely resembled the rest of the Mojave Desert's scrubby vegetation, and cooler temperatures allowed for more water to be present across the region. A shallow lake permanently occupied what is now called Badwater Basin, and other marshy regions were found along the length of Death Valley. As the body of basaltic magma rose to the surface, it encountered the significant groundwater deposits present. When lava meets water, explosive things happen.

(looking SW along the Tin Mtn. Fault)

A phreatomagmatic eruption occurs when magma encounters water and creates a near-continuous steam explosion. Ubehebe Craters consists of about 15 explosion craters, called maars. These many craters probably all formed about the same time, with the main Ubehebe Crater being the last one formed and therefore not filled with volcanic ejecta and debris. As the steam-magma slurry rose, it blasted through the surrounding rock which is a conglomerate composed of solidified alluvial fans coming off the surrounding mountains. Of the material erupted and thrown across the landscape, only about 1/3 of it is lava! The dark blanket surrounding the volcanic field consists mostly of fragments of this conglomerate baked and altered by its proximity to lava. You can find basaltic cinders with chunks of conglomerate trapped within, often baked orange or white by the heat.

The main Ubehebe Crater is quite large, about 800 m wide (1/2 a mile) and 270 m deep (800 feet). There's a steep and slippery path to the bottom, from which you can get a true appreciation of the size and power available in the inside of a volcano. The surrounding layers of alluvial conglomerate are faulted and cooked, showing that this area has seen some intense geologic activity in its lifetime.

Brown and gray layers show the surge deposits left by individual explosions during the eruptive period which probably lasted between a few days and several weeks. They sit directly atop the preexisting arroyo/bajada/alluvial fan surfaces.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Taking a stroll in the ephemeral brines of Death Valley.

As a basin completely isolated from the sea, Death Valley is the ultimate sink and final destination for all of the surface and groundwater for an immense area of eastern California and central Nevada. Following an unusually wet summer and winter of 2023/2024, a lake as deep as 3 feet filled the salt pan on the flood of Death Valley and brought back a glimpse of how it must have looked when the valley contained a permanent lake in the geologic past.

Strong winds during my last visit actually pushed the lake some two miles to the north, churning up the sediment and mud of the lake bottom and turning the water to the color and consistency of chocolate milk. As the salty water evaporates from the surrounding mud, it draws the salt into long, threadlike crystals that turn the salt flats fuzzy for a brief time.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ubehebe Crater

At the north end of Death Valley sits a small volcanic field. About 2,100 years ago, a body of basaltic magma forced its way to the surface along the Tin Mountain Fault, reaching the surface near the floor of Death Valley.

2,100 years ago, Death Valley was a different place. It more closely resembled the rest of the Mojave Desert's scrubby vegetation, and cooler temperatures allowed for more water to be present across the region. A shallow lake permanently occupied what is now called Badwater Basin, and other marshy regions were found along the length of Death Valley. As the body of basaltic magma rose to the surface, it encountered the significant groundwater deposits present. When lava meets water, explosive things happen.

(looking SW along the Tin Mtn. Fault)

A phreatomagmatic eruption occurs when magma encounters water and creates a near-continuous steam explosion. Ubehebe Craters consists of about 15 explosion craters, called maars. These many craters probably all formed about the same time, with the main Ubehebe Crater being the last one formed and therefore not filled with volcanic ejecta and debris. As the steam-magma slurry rose, it blasted through the surrounding rock which is a conglomerate composed of solidified alluvial fans coming off the surrounding mountains. Of the material erupted and thrown across the landscape, only about 1/3 of it is lava! The dark blanket surrounding the volcanic field consists mostly of fragments of this conglomerate baked and altered by its proximity to lava. You can find basaltic cinders with chunks of conglomerate trapped within, often baked orange or white by the heat.

The main Ubehebe Crater is quite large, about 800 m wide (1/2 a mile) and 270 m deep (800 feet). There's a steep and slippery path to the bottom, from which you can get a true appreciation of the size and power available in the inside of a volcano. The surrounding layers of alluvial conglomerate are faulted and cooked, showing that this area has seen some intense geologic activity in its lifetime.

Brown and gray layers show the surge deposits left by individual explosions during the eruptive period which probably lasted between a few days and several weeks. They sit directly atop the preexisting arroyo/bajada/alluvial fan surfaces.

#geology#california#adventures#rocks#bettergeology#photography#death valley#volcano#california geology#mojave desert#nationalpark#eastern california#lava

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

me: mom can we go to the grand canyon to see the great unconformity?

my mom: no sweetie, we have the great unconformity at home

the great unconformity at home:

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

#please just let me be a professor I’d be so good at it

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

On some nights, I can’t sleep. Sometimes, on those same nights, my lovely wife is with her family and I find myself sitting in the pallid glow of a single lamp wondering what to do.

If there’s anything that’s dependable, it’s the neighborhood dive bar that’s been in business for something near 90 years. I don’t often find myself drinking alone, but once in a while I get out to connect with the fellow neighborhood denizens that apparently populate the bar after 11:30 pm. It’s a surprisingly lively place on a surprisingly quiet stretch of road, and I wasn’t sure if I would be the only one or if it would be packed. There are nine others here with me now, and every time the door opens the heavy sent of wet pavement swirls in with a hint of cigarette smoke.

It hasn’t rained in Portland for a few days. The light drizzle has moistened the pavement just enough for the petrichor to rise. In here, it’s warm in temperature and feeling. A man in a pork pie hat is playing pinball, a nondescript ‘80s movie is playing on the single working TV, and all is well in the world from in here. We’re all sharing the slightly lonely, communal feeling unique to the local watering hole.

City living has its challenges. The human ecosystem is on complete display as well as the gamut of human experience. I doubt that living in the countryside would do me well; in the city we share everything in much closer proximity than they do in the country. Although the local watering hole is a universal constant, city dives are different in that you can come to the same bar 50 times and see a different slate of people every time. Everyone is talking about innocuous things: spray tans, lap dance bars, vacations, smokes, local colleges…

It’s all a vignette into the lives of strangers. After my glass is empty, I’ll doubtless walk out the door onto the quiet street and take a couple extra laps around the block before climbing into bed with the cats. Maybe I’ll see a skunk or a cat. It’s always novel to see the same homely neighborhood in the quiet of night. I’ve lived here for seven years, and that feels so wrong. I found the place I want to spend the rest of my life in my early 20s, starting where I should have ended, and I love every minute of it. The most momentous occasions in my adult life so far have happened here, within a ten minute walk of where I slowly drain my glass of local microbrew.

Tomorrow, I’ll wake up and go to campus to finish up my peer review edits. I have an orchestra rehearsal far too late at night. Between now and then, I’ll keep thinking. I’m at the intersection of the lives of strangers. Our streams of consciousness will go on.

Maybe I’ll move over to the bar.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

A natural spring gushes from the bluffs at Oaks Bottom Wildlife Refuge, Portland, Oregon, USA.

Rainwater percolates into the unconsolidated sand, gravel, and cobbles that make up the uppermost rock deposits found in East Portland. Over time, that water is slowly filtered through the ground and it eventually trickles directly out of this slope near the river.

#oregon#geology#photography#portland#pacific northwest#video#asmr video#soothing sounds#nature sounds#sounds#water#water sounds

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Gargoyle", near Artists Palette, Death Valley National Park, California.

In a steep, rugged canyon carved into the heart of the Black Mountains, a massive hunk of stone juts weightlessly into the air. It's one of the most dramatic features in this canyon, and the many car-size boulders on the canyon floor indicate that it's probably not the first of it's kind. Those same boulders remind us that, though stone has an air of permanence about it, this too shall crash to the gravel wash below.

#photography#california#rocks#adventures#my photography#original photography on tumblr#death valley#death valley national park#mojave desert

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Toiyabe Range, central Nevada, USA.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Titus Canyon, in Death Valley National Park, CA, is a popular dirt road that crosses through the heart of the Grapevine Mountains and descends through a narrow, deep canyon. Along the way, it passes through 550 million years of history including dramatic stacks of limestone and near-shore sedimentary deposits, much younger rocks containing fossil mammals and colorful volcanic deposits, and a 1920s ghost town founded on a famous con (read up on the history of "Leadfield" for that one).

Flash floods in the summer of 2023 washed out the road below Leadfield, lowering the canyon bottom to bedrock in a number of places and erasing most traces of a road having ever existed there. It won't reopen to vehicle traffic for a while, but the whole canyon is open to hiking. It's a much different experience to walk through the twisting narrows compared to driving the same route.

#geology#photography#california#adventures#rocks#death valley#death valley national park#original photography on tumblr#my photography

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Debris-flow breccia, Mosaic Canyon, Seath Valley National Park, California, USA.

#geology#photography#california#bettergeology#rocks#death valley geology#death valley national park#california geology

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maupin, Oregon

This town along the Deschutes River has long outgrown its railroad roots and is now the center of recreation on the lower Deschutes. It’s so quaint that it looks like the invention of a model railroad layout.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Keeping an eye out

Mount St. Helens is the most active volcano in the Cascades. It's major eruption in 1980 has been succeeded by about 10 other smaller eruptions and maintains near-constant microseismicity. The first pictures show one of the close-in monitoring stations at Windy Ridge. The USGS Cascade Volcano Observatory maintains a number of large monitoring stations close to the mountain, near the vent, where they've been armored to protect from eruptive activity. These stations typically include a seismometer (seismogram here), a GPS station (the white dome), and other equipment like geophones or a webcam. Volcanoes never erupt spontaneously, they are always preceded by some kind of activity - usually small earthquakes - and let you know when they're ready to go. St. Helens hasn't done anything since about 2010, taking a well-deserved rest after the major lava dome growth in 2004-2008.

Around the mountain to the southeast, you can hike through the Plains of Abraham's pumice fields and past the slot-canyon head of Ape Canyon to the rim of the Muddy River, where another monitoring station reports seismicity and GPS data. The GPS stations observe the shape of the volcano over time. As gas, fluids, and magma move around inside the mountain, the surface deforms. Rapid or dramatic deformation is often indicative of impending eruption or other activity, and is one of the most important parameters in the volcanologists' arsenal.

36 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm an Oregon amateur geologist (geomorphology is my jam) and I just wanted to thank you for your blog ❤️⛰️🌋🏞

You’re welcome, I’m glad you enjoy it!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The fact that I specialize in tectonics makes me really wonder why I don’t already have these.

I'm going to attend a two-day geology conference wearing these

23K notes

·

View notes

Text

High flow on the Trukee River through downtown Reno, May 2023. This high flow event followed the record-shattering snowfall in the Sierra Nevada of that past winter.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Keeping an eye out

Mount St. Helens is the most active volcano in the Cascades. It's major eruption in 1980 has been succeeded by about 10 other smaller eruptions and maintains near-constant microseismicity. The first pictures show one of the close-in monitoring stations at Windy Ridge. The USGS Cascade Volcano Observatory maintains a number of large monitoring stations close to the mountain, near the vent, where they've been armored to protect from eruptive activity. These stations typically include a seismometer (seismogram here), a GPS station (the white dome), and other equipment like geophones or a webcam. Volcanoes never erupt spontaneously, they are always preceded by some kind of activity - usually small earthquakes - and let you know when they're ready to go. St. Helens hasn't done anything since about 2010, taking a well-deserved rest after the major lava dome growth in 2004-2008.

Around the mountain to the southeast, you can hike through the Plains of Abraham's pumice fields and past the slot-canyon head of Ape Canyon to the rim of the Muddy River, where another monitoring station reports seismicity and GPS data. The GPS stations observe the shape of the volcano over time. As gas, fluids, and magma move around inside the mountain, the surface deforms. Rapid or dramatic deformation is often indicative of impending eruption or other activity, and is one of the most important parameters in the volcanologists' arsenal.

36 notes

·

View notes