#A Special Day

Text

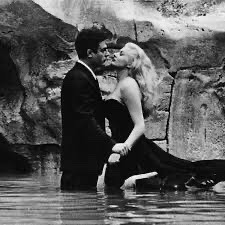

“Meeting you, getting to know you, talking with you, spending the whole day with you—today of all days—has been very important to me...”

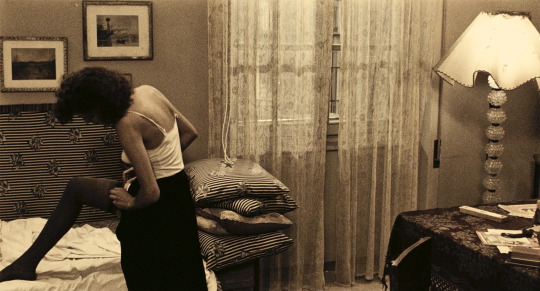

A Special Day (1977) dir. Ettore Scola

#a special day#una giornata particolare#ettore scola#sophia loren#marcello mastroianni#worldcinemaedit#filmauteur#filmgifs#italian movie#italian cinema#ellisgifs#queue

142 notes

·

View notes

Photo

THE CRITERION CHALLENGE 2023 — WEEK 1: RANDOM GENERATED SPINE NUMBER: #778

UNA GIORNATA PARTICOLARE/A SPECIAL DAY (dir. Ettore Scola, 1977)

#una giornata particolare#a special day#ettore scola#sophia loren#marcello mastroianni#usercriterion#cc23#criterion challenge 2023#*

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not yet

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

A very happy birthday to the fabulous Paul McGann!

Happy birthday to the wonderfully talented, (not to mention handsome) Paul McGann! Born on Saturday, November 14, 1959.

Wishing all the best for a lovely day!

#this was a labor of LOVE#it was getting late#and I wasn't sure if I was going to be able to make and post this on time#due to a very busy weekend#but here we are!#IT'S A MCGANN MONDAY INDEED#Happy birthday Paul!#a special day#determination brought me here#and now I'm ready to sleep#Ahhhh!!!!#thanks for everything PMG!#anyway#enjoy these beauties!#paul mcgann#the petrol age#nice town#paper mask#the merchant of venice#eighth doctor#doctor who the tv movie#the enemy within#the night of the doctor#the rainbow#withnail and I#hotel!#McGann Birthday Monday#McGann Monday#I McGann't Even

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

lol Of course, there will be birthday artwork for @silverwingstorm during ArtFight, This was made on the coincidence that Silver's birthday and the Barbie movie both fell on the same day!!☝️🤓

well hope you like Barbie fashion :D

This drawing was made on 21 July 2023 Team Vampires

#illustration#art#digital art#colors#artfight#artfight 2023#colorful#team vampires#bat#happy birthday#26#a special day#barbie fashion#pink#glitter#outfit#barbie movie#the barbie movie#barbie 2023

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Special Day (1977) dir. Ettore Scola

Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels (1975) dir. Chantal Akerman

#a special day#ettore scola#jeanne dielman#Jeanne Dielman 23 Commerce Quay 1080 Brussels#chantal akerman#italy#Belgium#1970s#slice of life#psychological#women directors#double bill suggestions

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Only love for Erend Vanguardsman allowed on this blog ✌️

And justified criticism of his character writing in HFW because….you know

#horizon forbidden west#horizon zero dawn#erend#erend vanguardsman#gtfo of here#with your hate#and annoyance#cause I ain’t having it#I love him#john hopkins#voice actors#he’s brilliant#nothing can change my mind#and don’t worry#a special day#is coming up#just for him#so nehh

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

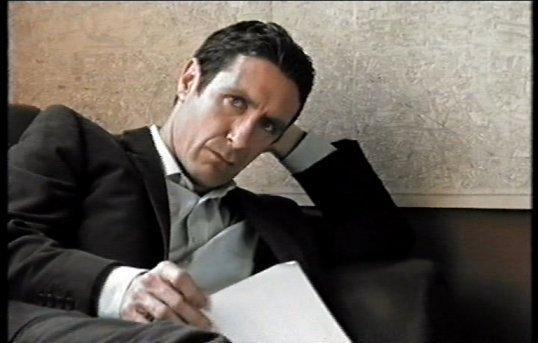

A Special Day (1977, Italy)

Two months after the Anschluss (Nazi Germany’s annexation of Austria), Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini made the most public show of their growing political relationship to date. Hitler’s arrival in Rome on May 3, 1938 and the public celebrations the next day saw the Eternal City festooned for pomp and circumstance. Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy’s military alliance was all but an inevitability, formalized the following year. None of these celebrations appear in Ettore Scola’s A Special Day (Una giornata particolare), but they help set the movie’s tenor and themes. Its two central stars, Sophia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni, are one of the great screen duos of film (this is their seventh of eight films together). Both Loren and Mastroianni suffered in the Second World War – the former was wounded in an Allied bombing raid in Pozzuoli (near Napoli); the latter was imprisoned in but later escaped from a Nazi labor camp. Their memories of those darker days made their experiences shooting A Special Day a needed emotional release.

In interviews, Loren often cites A Special Day as one of her favorite roles and movies of her own. Viewing this for the first time, that is no surprise to yours truly. This is a remarkable film with two raw performances from Loren and Mastroianni – departing from their glamorous personas to inhabit two working class individuals on society’s edge. A Special Day also benefits from Scola’s intimate and patient direction. All while creating a space that takes the audience back to a day that sealed the fates of not only our two protagonists, but millions of other innocent lives.

In a tenement apartment complex on the morning of May 4, 1938, housewife Antonietta Taberi (Loren) prepares breakfast for her husband, Emanuele (John Vernon), and their six children. Emanuele is a committed fascist, and plans on taking their spoiled children to view the parade set to feature Hitler and Mussolini. And it appears that almost everyone in the complex is heading off to the festivities as well, save apartment custodian Pauletta (Françoise Berd) and a neighbor across the way. When the family’s myna bird accidentally escapes their apartment, Antonietta receives help from Gabriele (Mastroianni), a recently-sacked radio announcer who largely keeps to himself. Over the remainder of the morning and afternoon in both his apartment and hers, Antonietta and Gabriele – whose firing was due to his homosexuality and anti-fascist politics – reflect on their lives, the expectations hoisted upon them by others.

Scola, better known as a political satirist (1962’s Il sorpasso, 1974’s We All Loved Each Other So Much) at this time, dispenses of his comedic roots in this screenplay with Ruggero Maccari (Il sorpasso, 1965’s I Knew Her Well), and Maurizio Constanzo (1968’s The Vatican Affair). The film begins with several minutes of propagandistic archival footage hailing Hitler’s visit to Italy, its narration vociferously extoling this show of authoritarian solidarity. Through most of the film, one can hear in the distance (and over radios) the triumphant parade as it winds its way through the Roman streets. It is an omnipresent reminder both our protagonists are in a trap.

Antonietta and Gabriele bristle under societal norms. For Antonietta, there is unspoken tension with her husband. He has been philandering with other women, specifically highly-educated women – all of which feeds into Antonietta’s insecurities that she never received a proper childhood education. But despite that lack of schooling, Antonietta expresses an interest in the world outside the apartment complex – she makes her best attempt to read literature and understand the subtexts of the works she reads, and she is anything but politically apathetic. She is not merely a housewife, nor does she wish to be seen as merely a housewife. But she finds herself unable to express this to her husband, and wishes not to plunge her children’s lives into chaos. Straying from being a homemaker, at this time, would almost certainly run afoul of fascist gendered norms. Here, with wonderful assistance from makeup artist Franco Freda (1961’s Divorce Italian Style, 1972’s Avanti!), Loren sheds her stylish visage, transforming into a woman older than her age, naïvely going along with her husband’s politics, living life largely the same way day after day. She, like her costar, disappears into the role – shorn of her fiery charisma, yet retaining only a glint of her stardom in her lonely glances to the camera.

Mastroianni, so often cast as the fashionable lover, is a gay political dissident in A Special Day who alternates between amusement and melancholy. Unlike Loren’s Antonietta, Mastroianni’s Gabriele is a man who chooses to hide his politics, his homosexuality, and his very being. In 1977, there was no previous Mastroianni performance that could serve as an analogue to this. Within the confines of A Special Day, we find in Gabriele a man whose tragedy is that he has never lived to experience the fullness of his humanity – always self-censoring, self-denying, all to ensure he survives under the fascist regime. One of the final moments that Gabriele shares with Antonietta is bravura acting from both Mastroianni and Loren. It is a scene that exemplifies how Gabriele has long had to “pass” as straight, but the film nevertheless reaffirms his homosexuality.

Then and now, Italian’s traditional Catholicism or Catholic-influenced values dictates the rights of queer individuals. Though same-sex activity has been legal in Italy since 1890, there remains a lack of legal protections for LGBTQ+ Italians in many other aspects of public and private life. Under Mussolini’s fascist regime, queer Italians faced persecution and spells in prisons and labor colonies. Gay men, in particular, were seen as agents of depopulation, effeminate undesirables in a new Italian empire built in the image of Benito Mussolini’s virile machismo. A Special Day keeps Gabriele’s homosexuality under wraps via implication until an emotionally fraught scene in which Antonietta believes that he is making advances towards her.

Mastroianni was not gay. And one imagines that, in contemporary cinema, a straight actor playing a gay character might result in justified hand-wringing. This remains an open debate, but I can imagine Italian cinema (and Italian society) was not quite ready for an openly gay actor in the 1970s. The matter-of-fact presentation of his queerness ensures that Gabriele’s sexual orientation is not the primary definition of his being, as might be the case in too many lesser films, past and present. Even during and after a scene that appears to contradict his homosexuality, his characterization remains steadfast.

Cinematographer Pasqualino De Santis (1968’s Romeo and Juliet, 1981’s Three Brothers) drains most of the frame of its color. The desaturated palette half-resembles a faded photography from the early twentieth century, which sometimes have selective coloring. A Special Day’s sepia dominates the frame all but twice: the opening minutes of the archival footage (regular black-and-white) and the green and reds of the flags of Italy and Nazi Germany. As much as I am no fan of desaturated colors in cinema, A Special Day is not responsible for modern mainstream filmmakers’ tendency to favor desaturated color palettes.

Shortly after the opening archival footage, an impressive crane shot lingers outside the windows of the apartment building in the early morning until it slowly glides its way into Antonietta’s apartment, following her as she awakens her children and husband for the festivities to come. The effect is seamless, seemingly uninterrupted by cuts for four minutes (there may be a “hidden” cut in there that I did not detect), and sets the unrushed tempo of the film. De Santis’ camera is unobtrusive, capturing the ramshackle conditions of the apartments all while endowing the viewer a sense of the apartments’ layout. In addition, A Special Day’s long, unbroken takes allow the audience to reflect on the emotions and experiences shared between our two protagonists. My reservations over the colors aside, this is one of the most beautifully photographed films of its decade.

In 106 minutes, A Special Day launches into an examination of how Italian fascism impacted the lives of the nation’s most vulnerable individuals – in this case, women, political dissidents, and LGBTQ+ individuals. The film does so without resorting to sensationalism or hysterics, preferring instead measured discussion and tragic implications. Antonietta and Gabriele’s use of language and stated reservations exemplify fascism’s role in devaluing the individual in service of an ideology. A few decades removed from the end of the Italian neorealism movement, strands of neorealism are apparent across A Special Day. One sees it in the quiet desperation of Antonietta and Gabriele, the unglamorous presentation of tenement life, and the hardscrabble scenario of the film (it is just missing Italian neorealism’s penchant for green, nonprofessional actors).

Essentially a chamber piece, Ettore Scola’s A Special Day is accessible, keenly felt, beautifully shot, and wonderfully acted. Loren’s Antonietta and Mastroianni’s Gabriele truly share a special day together – a day without the rhythms of their usual lives, without the distractions of family, friends, and (most) of their acquaintances and neighbors. By film’s end, they are fully themselves in each other’s presence, relating in one another their desires crushed underneath the weight of fascism’s demands. There is no guarantee a day like this will come again, as both Antonietta and Mastroianni realize and accept. All that remains for our protagonists is survival, with moments of individual resistance so unassuming that they might be invisible to all but themselves.

My rating: 10/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. A Special Day is the one hundred and sixty-seventh feature-length or short film I have rated a ten on imdb (the 166th, 2021's Drive My Car, has not received a write-up on this blog). My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog. Half-points are always rounded down.

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

#A Special Day#Una giornata particolare#Ettore Scola#Sophia Loren#Marcello Mastroianni#John Vernon#Françoise Berd#Ruggero Maccari#Maurizio Costanzo#Pasqualino De Santis#Franco Freda#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Special Day (1977) Ettore Scola

#a special day#ettore scola#worldcinemaedit#filmauteur#sophia loren#marcello mastroianni#filmgifs#una giornata particolare#italian movie#italian cinema#ellisgifs#this shot…………..#queue

113 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Una giornata particolare, Ettore Scola, 1977

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

my edit

made by me using capcut

song: another love

pictures are ftom pinterest ;)

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#robert sugden#robron#with#a bear a passport a phone and...seb#all on one day#a special day#the leather jacket#the dark blue shirt#looks good#260718#my set

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

I think you'd be a great person to have deep talks with. (:

Guys, what's up with the compliments today?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

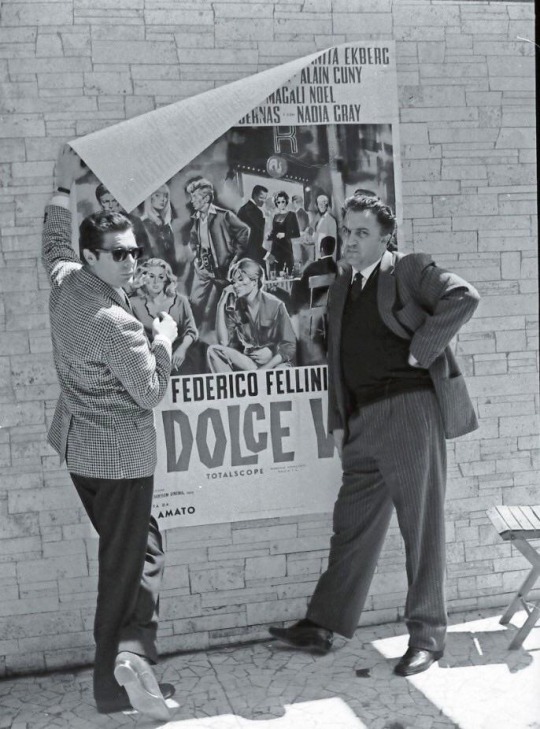

The happiest of birthdays in the afterlife to Marcello Mastroianni!

#marcello mastroianni#la dolce vita#8 1/2#marriage italian style#sunflower#a special day#divorce Italian style#la notte#the big feast#city of women#dark eyes#the assassin#ready to wear#used people#big deal on Madonna street#Roma#the stranger

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

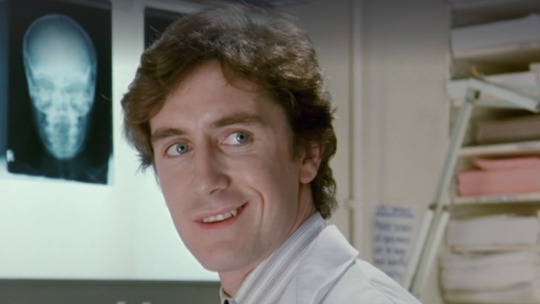

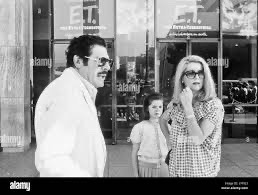

Two With Marcello Mastroianni

A Slightly Pregnant Man (Jacques Demy, 1973)

Catherine Deneuve and Marcello Mastroianni in A Slightly Pregnant Man

Cast: Catherine Deneuve, Marcello Mastroianni, Micheline Presle, Marisa Pavan. Screenplay: Jacques Demy. Cinematography: Andréas Winding. Production design: Bernard Evein. Film editing: Anne-Marie Cotret. Music: Michel Legrand.

A Special Day (Ettore Scola, 1977)

Marcello Mastroianni and Sophia Loren in A Special Day

Cast: Sophia Loren, Marcello Mastroianni, John Vernon, Françoise Berd. Screenplay: Ruggero Maccari, Ettore Scola, Maurizio Costanzo. Cinematography: Pasqualino De Santis. Production design: Luciano Ricceri. Film editing: Raimondo Crociani. Music: Armando Trovajoli.

The great charm of Marcello Mastroianni lies, I think, in the fact that he always seems to be the odd man out. Despite his good looks and sex appeal, there is always the sense that the characters he plays, even though they attract women on the order of Catherine Deneuve and Sophia Loren, are never quite in charge of the world they inhabit. Certainly this is true of his most famous roles, Marcello in La Dolce Vita (Federico Fellini, 1960) and Guido in 8 1/2 (Fellini, 1963). And directors Jacques Demy and Ettore Scola exploit this otherness in Mastroianni in very different ways: Demy in the satiric A Slightly Pregnant Man and Scola in the earnest A Special Day. In the former film, whose French title was the lengthy L'Événement le plus important depuis que l'homme a marché sur la Lune (The Most Important Event Since Man Walked on the Moon), Mastroianni plays Marco, a driving-school instructor who feels out of sorts and goes to see a doctor who decides that he must be pregnant. When a well-known specialist confirms the diagnosis and presents his findings to other scientists, the press goes wild and the advertising department for a maternity-wear company launches a campaign for male maternity clothes. Marco winds up on posters everywhere, and he and his fiancée, Irène (Deneuve), begin to make big plans for the money the company pays him. Eventually, the diagnosis proves to be false, however, and the film concludes with an anticlimactic thud. Demy, whose best-known work is probably the cotton-candy musicals The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964) and The Young Girls of Rochefort (1967), seems to have launched into his screenplay with no sense of how to end it satisfactorily. Until that point, however, Mastroianni and Deneuve have fun with their roles. Forgoing her usual sophisticated chic, she plays a somewhat blowsy beauty-shop owner. A Special Day earned Mastroianni one of his three Oscar nominations, partly because there's nothing the Academy likes better than a straight actor daring to play gay. He is Gabriele, a radio announcer who has lost his job because the Fascists have begun purging the work force of "undesirables." The day is May 8, 1938, when Hitler visits Mussolini in Rome to solidify their alliance. He lives in a large apartment complex with windows facing an open courtyard. Across the way lives Antonietta (Loren), a woman with an abusive husband and six children. On this day, she has stayed home to clean house after sending her family off to the parades and speeches, but when the family's pet mynah bird escapes and flies out into the courtyard, she asks Gabriele's help in retrieving him. They are virtually the only people left in the complex other than the nosy, gossipy concierge, whose radio is blaring the news of the day -- Fascist anthems, speeches, the cheers of the crowd, and a running patriotic commentary -- which serves as the sometimes ironic counterpoint to the growing intimacy of the mismatched couple. A severely deglamourized Loren gives a fine performance, as does Mastroianni: Gabriele is aware that at any moment he may be taken away to a concentration camp, and he vacillates between suicide and a carpe diem fatalism. The film is a little too predictable, and although the screenplay by Scola and Ruggero Maccari is original, it feels somewhat like an adaptation of a two-character stage play. Pasqualino De Santis's cinematography, using long takes and tracking shots through the apartment complex (which we never leave except in the archival newsreel footage at the film's beginning), helps open it up.

#A Slightly Pregnant Man#A Special Day#Jacques Demy#Ettore Scola#Marcello Mastroianni#Catherine Deneuve#Sophia Loren

6 notes

·

View notes