#Chapelle Sainte-Anne

Video

Maison en bord de Seine par Catherine Reznitchenko

Via Flickr :

Ancienne chapelle Sainte-Anne de l'ancien château fort de La Fontaine, Saint-Pierre-de-Varengeville, Seine-Maritime, Normandie, France. www.catherine-reznitchenko.fr

#landscape#Forest#trees#chapel#Sainte-Anne#Chapelle Sainte-Anne#Saint-Pierre-de-Varengeville#church#outdoors#River#Seine-Maritime#Seine river#Quais de Seine#Seine#Forêt#Paysage#arbres#chapelle#extérieur#Normandie#automne#autumn#season#saison#XVe siècle#house#fleuve#La Seine#water#maison

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

LÉGENDE | Sainte Anne et la chapelle de Jard-sur-Mer (Vendée) ➽ http://bit.ly/Chapelle-Sainte-Anne Une légende se rapporte à la construction d’une chapelle dédiée à sainte Anne sur la commune de Jard-sur-Mer, en Vendée, placée dans le bourg, presque à son extrémité ouest, et qui ne présente, en tant que monument, rien de curieux. Sur une pierre placée au dessus du portail est gravée la date de 1652, probablement de l’achèvement complet de l’édifice...

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saint Anne is the patron of Indigenous Canadians and this began, arguably, with devotion to Saint Anne among the Mik'maq. Devotion to Saint Anne among the Mik'maq is widespread, She is absolutely beloved, She is known as the Grandmother of the Mik'maq.

In 1610 Grand Chief Membertou, along with twenty one members of his family, converted to Catholicism. While we can speculate on the conviction of his conversion, we do know that Grand Chief Membertou converted to solidify his relationships and trading with the French colonists. In 1628 Saint Anne was chosen as the patron saint of the Mik'maq.

Every year on the feast day of Saint Anne many Mik'maq will make a pilgrimage to Mniku (Chapel Island) off the coast of Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. Mniku traditionally has always had deep significance among the Mik'maq it being where the yearly gathering of the Mik'maq Grand Council, as it is still done, would take place on Mniku.

The Mik'maq will have a procession and gather at Saint Anne's Church. A Mass of Saint Anne is performed in the church and from there dancing, singing, community gathering and feasting are done outside the church.

A custom done by the Women's Council during the feast of Saint Anne is to wash Her statue with cloth which is then cut into strips that are given out to members of the community. Saint Anne's Ribbons are believed to provide protection, healing, and to uplift the receiver. The ribbons are word around the wrist or ankle.

Another custom performed during the feast day of Saint Anne is Her statue will be carried in procession to "the stone", a boulder on which it's said a French priest said the first Mass on Mniku. There the Santé Mawi'omi (Mik'maq Grand Council) members will offer words of wisdom as will the priest of Saint Anne's Church.

Photos:

1. Saint Anne's statue, draped in a traditional Mik'maq woman's cloak and rabbit fur, carried in procession. 2. Procession to Saint Anne's Church. 3. Dancing and singing in front of Saint Anne's Church. 4. Saint Anne's Ribbons on a picture of Mniku (Chapel Island).

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I absolutely do not believe in common sense. There is sense, but there is no common variety. In all likelihood, not a single one of you hears me in the same sense as another. Furthermore, I endeavour to make it so that access to this meaning is not so easy, which entails you having to put something of your own into it.”

Jacques Lacan, Talking to Brick Walls, a series of talks at Sainte-Anne Chapel

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

{Location: Fogmorre Castle, Avon County, Kingdom of Wessex}

Head Mover: We should have everything moved into their proper rooms before your family arrives, ma'am.

Queen Anne II of Wessex: And Christian says that he couldn't find his back brace this morning. If you could have someone find the box that it's in and bring it into our dressing room. that would be most appreciated.

Head Mover: Not a problem, I'll get someone to check the list now to see where it is.

Anne II: I say. I’m impressed how quickly you’ve moved all of our belongings from Claremont House into Fogmorre Castle.

Head Mover: Thank you ma’am, my staff has been preparing for the move for awhile now. Though…

Head Mover: …(continued) and if I may ask ma'am, we were originally told to prepare two rooms for The Crown Prince and The Crown Princess. That is one for both of them and one for Prince Richard.

Anne II: (uncomfortable) Yes well.

Head Mover: But talking to the Crown Prince's team it sounds like their Royal Highnesses would prefer separate rooms.

Anne: … Yes, very well. Prepare the Tower Suite for William, it's already furnished nicely, and shouldn't need too much.

Staff: And Margaret, ma'am?

Anne II: Move any boxes or furniture from Claremont House marked B into the Double Suite for Margaret and Richard. We can move it after the weekend after All Saints Day.

Prince Arthur, The Earl of Falmouth: (off screen) There you are, your staff told me you were looking for me.

Anne II: Yes, its been a busy morning. I've been meaning to pop by.

Prince Arthur: No need for apologies, I can imagine everyone around here is keeping you on your toes (chuckles).

Anne II: I'm sure you heard about old Lord Poole.

Prince Arthur: It's such a shame having an old friend pass away. I figured you'd want someone from the family to represent you at the funeral? I'd of course be willing.

Anne II: That's very thoughtful. But I wanted to talk to you about the Order of the Royal Chrysanthemum. With his death a new spot has opened up, and since you are the Grand Master of the order, I'd figure I would talk to you first.

Prince Arthur: ...yes well. There are a few strong candidates in the National Council that are Peers. Though inducting someone involved in the sciences or Cancer research would be a way to honor Lord Poole.

Anne II: Well, actually I was thinking about nominating William to take Lord Poole's seat.

Prince Arthur: William, do you think he's ready?

Anne II: I'm not sure if ready is the word. He's seems so lost lately, it's as if he's lost his connection to the Crown. He needs something to reaffirm his sense of commit and purpose to the monarchy.

Prince Arthur: Well if he is meant to be Sovereign of the Order one day, I see no reason for government to deny his knighthood.

Anne II: Does that mean I have your support?

Prince Arthur: I think it's a wonderful idea. We can have a proper ceremony planned in about a month or two.

Anne II: What about sooner?

Prince Arthur: How soon?

Anne II: I'd want it done during the upcoming Devon Tour. We can convene the Order then. I can inform my staff to make all the necessary arrangements at Exeter Chapel.

Prince Arthur: All the same to me, if you're sure?

Anne II: More than anything.

Beginning | Start of Current Chapter | Previous | Next

#sims 4 royalty#sims 4 royal family#sims 4 royal simblr#sims royal family#sims 4 royals#sims royal#sims 4 royal#familytale

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Statue surmounting the Saint-Anne chapel of the convent of the Sisters of Divine Providence in Saint-Jean-de-Bassel, France +

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sub Fellas

I'm Anamaria, but you can also call me Annie or Ann (whatever you want, like Idk BUT JUST NEVER CALL A MONSTER BUT ,ALSO NICE !)

Here some fun facts about me :

I'm a Beast of Revelation

I'm a human made by Satan

I was made by the root of Eden Tree, blood of my mom Persephone (Witch of Endor) and blood my my dad (or another mom) Serpent of Eden (I think he was called Crawly, but then he changed his name ? Idk ¯\_(ツ)_/¯)

I love rock music, especially Marina, Bon Jovi, AC/CD, Guns 'n' Roses and Nirvana. Queen is kinda cool too

Favourite animal ? Crows - duh ?!

I currently live in a hunted cemetry chapel in Kirkham (It's a village near Blackpool ig, I know, middle of nowhere)

I speak english, greek, arabic, latin and german

In my chapel, there is also my roomie, Josephine. She's a saint and also she's a St. Joseph's grandauther

I'm autistic, dyslexic and have ADHD

I'm also a grafitti artist

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Saint Anne’s chapel inside the cathedral, Tudela (Nafarroa).

18th century, incredible churrigueresque style.

Pic sources: 1, 2 & 3

#nafarroa#euskal herria#basque country#pais vasco#pays basque#tudela#erribera#architecture#art#churrigueresque#incredible#photography#travel#places#wanderlust

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE CONVERSION OF A FORMER SATANIST TO A CATHOLIC WARRIOR AND A PRO-LIFE ADVOCATE

(The Miraculous Medal, the Blessed Mother and the Miraculous Conversion of a Satanic “High Wizard” to Jesus Christ)

An average boy in an average American neighborhood, Zachary King grew up in a Baptist home. He began practicing magic at ten years old, joined a satanic coven at thirteen years old, and by the time he was fifteen years old, he had broken all the Ten Commandments!

From his teen years to adulthood, Zachary worked his way up to High Wizard in the coven and actively pushed Satan's agenda, including ritualistic abortions and breaking up churches.

In January of 2008, Zachary was working as a manager at a jewelry store. A lady customer by the name of Mary Ann came into the store and told him “the weirdest thing.” She put a gold disk in his hand and said to him, “The Blessed Mother is calling you.” Although he said that he knew the Miraculous Medal had “no power,” he was terrified of the Medal.

“I clenched my fist around it and I fell into this darkened void.

“Then the Blessed Mother appeared, took me by the hand and turned me around, and there was Jesus, standing behind me.

“When the Blessed Mother took me by the hand, the Jesus that I saw was the Divine Mercy Jesus,” he added, referring to the depiction of Jesus in the Divine Mercy Image, which the Lord instructed St. Faustina to have painted in 1931.

“I did not know what the rays meant, but the rays were all around me, going through me.”

Mr. King knew immediately that this person was Jesus and that everything he had ever done previously in his life was wrong.

Our Lady's love rescued Zachary from Hell and brought him straight to the Heart of Her Son, Jesus Christ. He started spending hours in the Adoration Chapel and he soon joined the Catholic Church.

Zachary became familiar with Divine Mercy. When he saw the Divine Mercy Image for the first time, he realized that it was the same image he had seen when he was given the Miraculous Medal and the Blessed Mother took him by the hand.

Mr. King believes that the Lord gave him this image, because He wanted him to know that he could be forgiven. “Divine Mercy was my salvation,” Zachary said.

“Satan attacks you at any age,” said Mr. King. “He starts attacking you in the womb. From the moment you are conceived, you are under attack.”

To protect oneself from the devil, Mr. King recommended: “Confession every seven days. Everybody can use a blessing. Only receive the Eucharist in a state of grace and adoration.”

After 26 years of involvement in the occult, Zachary has become a warrior for Jesus Christ. He works with exorcists, started “All Saints Ministry” in 2010, and is a strong Pro-Life advocate.

“𝐴𝑏𝑜𝑟𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝑖𝑠 𝑎 𝑆𝑎𝑡𝑎𝑛𝑖𝑐 𝑆𝑎𝑐𝑟𝑖𝑓𝑖𝑐𝑒”

~ Zachary King

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

František Kupka (1871-1957), Le Cheval blanc, la Chapelle Sainte-Anne devant la mer, Trégastel (The White Horse, Saint Ann’s Chapel before the Sea, Trégastel), 1909, oil on canvas.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

SAINT OF THE DAY (December 19)

St. Berardo Valeara of Teramo OSB (c. 1050 - 1122)

Saint Berardo was born into the noble family da Pagliara, whose castle bore their name near the town of Isola del Gran Sasso in the Abruzzo region of Italy.

Important information concerning his life is found in the ancient church records from this area as well as the chronicles of his successor, the Bishop Sassone.

Saint Berardo entered the monastery in Montecassino as a young man and was later associated with the Abbey of San Giovanni in Venere.

He became well known for his good works, and upon the death of the Bishop Uberto, Berardo was asked to become a pastor in the territory of Teramo.

He took on this role for seven years beginning in 1116 and focused his efforts on helping the poor and making peace amongst the warring factions of the local citizenry.

He died on 19 December 1122 of natural causes.

He was buried in what today is known as Saint Anne’s chapel in the ancient Teramo Cathedral of Santa Maria Aprutiensis (now Sant’Anna dei Pompetti).

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rolling Stones singer Mick Jagger and his bride, Bianca Perez-Mora Macias, are shown during their wedding in the Sainte-Anne chapel, May 12, 1971, Saint Tropez, France.

#st tropez#bianca jagger#keith richards#rolling stones#mick jagger#rhythm and blues#rock and roll#charlie watts#stones sixty#bill wyman#mick taylor

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

ok I want to try my luck again with the WIP word guess - kneel?

Now that's definitely a word that's going to show up frequently in a novel about Richard II, and so indeed it does! Putting some of it behind a readmore because there's a lot of sentences and a couple of them get a little blue. ;)

Richard feels his heart catch in his throat, and he kneels beside the bed.

There is a faldstool in front of him and he remembers he is supposed to kneel. He is helped down from the coronation chair (they have to remove the cushions first) and when he stands upright he is dizzy for a moment and his eyesight blurs around the edges. He kneels, slowly and carefully, on the faldstool as Archbishop Sudbury says one final set of prayers.

Richard kneels on the faldstool again, and as the archbishop intones “Coronet te Deus corona gloriae atque iusticiae…” he can barely hear it over the sound of his own heart thundering in his ears.

John of Gaunt, as the highest-ranking of all the nobles, goes first; he kneels at Richard’s feet and says, in a clear and even voice, “I, John of Lancaster, do become your liege man of life and limb and of earthly worship, and faith and truth I shall bear unto you, to live and die against all manner of folk.” His face is carefully expressionless.

The youngest person knighted today is his little cousin Edward, who is barely four years old and is guided to the dais by his father, the Earl of Cambridge. He gazes up at Richard with awestruck eyes and has to be nudged by his father to remember to kneel.

In the dark, he stumbles toward his prie-dieu—he could open the door and ask a servant for a candle, but he doesn’t feel like talking to anyone, even to order them around. He kneels clumsily; it is too dark to see his prayerbook.

“You are the King,” Archbishop Sudbury says. “I am your servant.” They kneel together, and Richard bows his head and closes his eyes as Sudbury intones: “Lord, watch over your servant Richard. Help him to lead wisely, and to do what is right. Grant peace once more to England. Forgive us our sins, and turn away your wrath.”

As soon as his feet touch the ground, the assembled company, as one, kneels.

He kneels in his oratory until it is late at night and his knees ache, praying to every saint he can think of, for the souls of the men who died today; for his own soul, if he has done the wrong thing; for guidance.

At the Abbey, he makes an offering at the altar and then climbs up into the chapel of the Confessor, where he kneels in one of the alcoves at the shrine. They aren’t built for people who are particularly tall; Richard has to bow his head a little, although he supposes it’s appropriate, in the presence of the saint.

The man in question kneels. “Ralph Standissh, squire of the realm,” he says, “and your Highness’ servant ever.”

Robert kneels astride his thighs and begins unbuttoning his doublet and when Richard closes his eyes because even Robert’s lightest touch is more than he can bear, the afternoon sun shines blood-red through his eyelids.

“You are awful, Robin,” Richard says, bounding up to kneel astride Robert’s hips. “I hope you know that.”

Below him, the two bishops are leading Anne down the long nave through the choir to the altar, which has been prepared with a pile of carpets and cushions. Anne kneels down upon these, very carefully, her hair and her purple robes flowing around her.

“Is it?” Anne gives him a heavy-lidded smile, and then before he knows it he’s on his back and she’s bent over him, her hair falling about his face as she kneels astride his hips, making him instantly, painfully hard.

All three of them kneel, wide-eyed in the presence of the King, even if the King is dressed only in his shirt and robe. He should probably have held this off until he’s had a chance to get dressed properly, Richard reflects, but it’s too late now.

He is not certain how long he’s been at prayer when Anne comes in and kneels beside him. The room is warmer for her presence. She turns toward him, a little, and examines his face. Her own face is pink and blotchy, her nose red and her eyelids swollen—she must have heard the news by now.

When Henry and Mowbray come to greet them, they do not kneel, only look at one another and make an awkward half-bow, as if they’d instinctually recognized Richard as the King and then thought better of it.

Then they kneel before him as one, so fluid once again as to have been rehearsed, but the smug expressions don’t leave their faces for a moment, and Richard wants to be sick.

Bishop Arundel, in his capacity as Lord Chancellor, has to make the customary speech about the parliamentary agenda; they can remain on their knees until he’s finished. And if Bishop Arundel objects to his brother having to kneel at length, he can abbreviate his speech accordingly.

#wip word guessing game#the novelthing#richard ii#your heart is up i know thus high at least although your knee be low

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

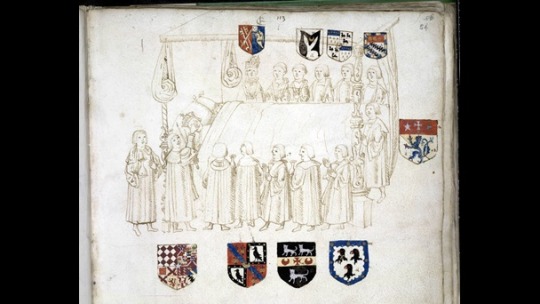

“Will of Henry VII”.

“At his manor of Richmond, 31 March Hen. VII., the King makes his last will, commending his soul to the Redeemer with the words he has used since his first "years of discretion," Domine Jesu Christe, qui me ex nichilo creasti, fecisti, redemisti et predestinasti ad hoc quod sum, Tu scis quid de me facere vis, fac de me secundum voluntatem Tuam cum misericordia, trusting in the grace of His Blessed Mother in whom, after Him, has been all his (testator's) trust, by whom in all his adversities he has had special comfort, and to whom he now makes his prayer (recited), as also to all the company of Heaven and especially his "accustumed avoures" St. Michael, St. John Baptist, St. John Evangelist, St. George, St. Anthony, St. Edward, St. Vincent, St. Anne, St. Mary Magdalene and St. Barbara, to defend him at the hour of death and be intercessors for the remission of his sins and salvation of his soul.

Desires to be buried at Westminster, where he was crowned, where lie buried many of his progenitors, especially his granddame Katharine wife to Henry V. and daughter to Charles of France, and whereto he means shortly to translate the remains of Henry VI.,—in the chapel which he has begun to build (giving full directions for the placing and making of his tomb and finishing of the said chapel according to the plan which he has "in picture delivered" to the prior of St. Bartholomew's beside Smithfield, master of the works for the same); and he has delivered beforehand to the abbot, &c., of Westminster, 5,000l., by indenture dated Richmond, 13 April 23 Hen. VII., towards the cost.

His executors shall cause 10,000 masses in honor of the Trinity, the Five Wounds, the Five Joys of Our Lady, the Nine Orders of Angels, the Patriarchs, the Twelve Apostles and All Saints (numbers to each object specified) to be said within one month after his decease, at 6d. each, making in all 250l., and shall distribute 2,000l. in alms; and to ensure payment he has left 2,250l. with the abbot, &c., of Westminster, by indenture dated _ (blank) day of _ (blank) in the _ (blank) year of his reign.

His debts are then to be paid and reparation for wrongs made by his executors at the discretion of the following persons, by whom all complaints shall be tenderly weighed, viz., the abp. of Canterbury, Richard bp. of Winchester, the bps. of London and Rochester, Thomas Earl of Surrey, Treasurer General, George Earl of Shrewsbury, Steward of the House, Sir Charles Somerset Lord Herbert, Chamberlain, the two Chief Justices, Mr. John Yong, Master of the Rolls, Sir Thos. Lovell, Treasurer of the House, Mr. Thomas Routhall, secretary, Sir Ric. Emson, Chancellor of the Duchy, Edm. Dudley, the King's attorney at the time of his decease, and his confessor, the Provincial of the Friars Observants, and Mr. William Atwater, dean of the Chapel, or at least six of them and three of his executors.

His executors shall see that the officers of the Household and Wardrobe discharge any debts which may be due for charges of the same. Lands to the yearly value of above 1,000 mks. have been "amortised" for fulfilment of certain covenants (described) with the abbey of Westminster.

For the completion of the hospital which he has begun to build at the Savoie place beside Charingcrosse, and towards which 10,000 mks. in ready money has been delivered to the dean and chapter of St. Paul's, by indenture dated _ (blank), his executors shall deliver any more money which may be necessary; and they shall also make (if he has not done it in his lifetime) two similar hospitals in the suburbs of York and Coventry.

Certain cathedrals, abbeys, &c., named in a schedule hereto annexed [not annexed now] have undertaken to make for him orisons, prayers and suffrages "while the world shall endure," in return for which he has made them large confirmations, licences and other grants; and he now wishes 6s. 8d. each to be delivered soon after his decease to the rulers of such cathedrals, &c., 3s. 4d. to every canon and monk, being priest, within the same and 20d. to every canon, monk, vicar and minister not being priest.

His executors shall bestow 2,000l. upon the repair of the highways and bridges from Windsor to Richmond manor and thence to St. George's church beside Southwark, and thence to Greenwich manor, and thence to Canterbury.

To divers lords, as well of his blood as other, and also to knights, squires and other subjects, he has, for their good service, made grants of lands, offices and annuities, which he straitly charges his son, the Prince, and other heirs to respect; as also the enfeoffments of the Duchy of Lancaster made by Parliaments of 7 and 19 Hen. VII. for the fulfilment of his will.

Bequests for finishing of the church of the New College in Cambridge and the church of Westminster, for the houses of Friars Observants, for the altar within the King's grate (i.e. of his tomb), for the high altar within the King's chapel, for the image of the King to be made and set upon St. Edward's shrine, for the College of Windsor, for the monastery of Westminster, for the image of the King to be set at St. Thomas's shrine at Canterbury, and for chalices and pixes of a certain fashion to be given to all the houses of Friars and every parish church not suitably provided with such.

Bequest of a dote of 50,000l. for the marriage of Lady Mary the King's daughter with Charles Prince of Spain, as contracted at Richmond _ (blank) Dec. 24 Hen. VIII., or (if that fail) her marriage with any prince out of the realm by "consent of our said son the Prince, his Council and our said executors."

Executors of this will shall be Margaret Countess of Richmond, the King's mother, Christopher abp. of York, Richard bp. of Winchester*, Richard bp. of London*, Edmond bp. of Salisbury, William bp. of Lincoln, John bp. of Rochester*, Thomas Earl of Arundel, Thomas Earl of Surrey, Treasurer General, Sir Charles Somerset Lord Herbert*, Chamberlain, Sir John Fyneux*, Chief Justice, Sir Robert Rede*, Chief Justice of C.P., Mr. John Yong*, M.R., Sir Thomas Lovell, Treasurer of Household, Mr. Thomas Rowthale*, Secretary, Sir Richard Emson*, Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, Sir John Cutte, Under-Treasurer General, and Edmond Dudley*, squire, of whom those marked (*) above (or seven of them) are to assemble at least once in every term for twelve days, and declare annually their account to the supervisor of this will hereby appointed, viz. the abp. of Canterbury for the time being.

On assuming the administration, the supervisor and the executors named as "superattenders" (those marked with * above) shall each receive 100l. in half yearly instalments of 50 mks.; and when the will has been fully executed they shall each receive 200l. and the other executors 100l.

Dated at [Ca]unterbury the [10th day] (fn. 3) of April 24 Hen. VII.”

Link: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/letters-papers-hen8/vol1/pp1-8

Fancast: Mark Rylance as older Henry VII. Gifs are not mine to claim, they are used to illustrate the character.

#Henry VII#Henry Tudor#Henry VII of England#King Henry VII of England#House of Tudor#Tudor dynasty#The Tudors#Tudor#Tudor England#religiosity in Tudor England#Catholic Church#Catholic Saints#will of a dying king#Margaret Beaufort#Edmund Dudley#Richard Empson#Charles Somerset#primary sources#Mark Rylance

18 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Although little of the original flooring remains in the surviving royal chapels, a small area of sixteenth-century tiling at Hampton Court suggests that it was floored in a white and black chequerboard pattern. The chapel windows were filled with stained glass. The east window at Hampton Court, installed by Cardinal Wolsey, is known through a surviving vidimus [...] and was subject to several important modifications by the king, who removed the image of the Cardinal and, after the fall of Anne Boleyn in 1536, ordered the removal of the image of St Anne: 'for the translating and removing of an image of Saint Anna and another of Saint Thomas in the high altar window off the chapel.'

Royal Palaces of Tudor England, Simon Thurley

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Kingdom of Kongo and Palo Mayombe: Reflections on an African-American Religion

Abstract

Historical scholarship on Afro-Cuban religions has long recognized that one of its salient characteristics is the union of African (Yoruba) gods with Catholic Saints. But in so doing, it has usually considered the Cuban Catholic church as the source of the saints and the syncretism to be the result of the worshippers hiding worship of the gods behind the saints. This article argues that the source of the saints was more likely to be from Catholics from the Kingdom of Kongo which had been Catholic for 300 years and had made its own form of Christianity in the interim.

Acknowledgements

Research funding for this project was supplied by Boston University Faculty Research Fund and the Hutchins Center of Harvard University. Earlier versions were presented at the Hutchins Center, and the keynote address at ‘Kongo Across the Waters’ in Gainesville, FL. Thanks to Linda Heywood, Matthew Childs, Manuel Barcia, Jane Landers, Carmen Barcia, Jorge Felipe Gonzalez, Thiago Sapede, Marial Iglesias Utset, Aisha Fisher, Dell Hamilton, Grete Viddal and Kyrah Daniels for readings, comments, questions and source material.

[1] Robert Farris Thompson, Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy (New York: Random House, 1983), pp. 17–8; see also Face of the Gods: Art and Altars of Africa and African America (New York: Prestel, 1993). For Cuba in particular, see David H. Brown, Santería Enthroned: Art, Ritual and Innovation in an Afro-Cuban Religion (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2003), p. 34 (with ample references to earlier visions).

[2] Georges Balandier, Daily Life in the Kingdom of the Kongo (New York: Allen and Unwin, 1968 [French Version, Paris, 1965]) and James Sweet, Recreating Africa: Culture, Kinship and Religion in the African-Portuguese World, 1441–1770 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003).

[3] Ann Hilton, The Kingdom of Kongo (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984), for the role of the Capuchins in discovering problems with Kongo's Christianity. John Thornton, ‘The Kingdom of Kongo and the Counter-Reformation’, Social Sciences and Missions 26 (2013): 40–58 contextualizes their role and their problems with Kongo's Christianity.

[4] Adrian Hastings, The Church in Africa, 1450–1950 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994); this position is often implicit in the many histories written by clerical historians such as Jean Cuvelier, Louis Jadin, François Bontinck, Teobaldo Filesi, Carlo Toso and Graziano Saccardo, whose work has presented modern editions of the classical work of the Capuchin missionaries, commentaries and at times regional histories, such as Saccardo, Congo e Angola con la storia del missionari Capuccini, Vol. 3 (Venice: Curia Provinciale dei Cappuccini, 1982–1983). For both a position of dependence on missionaries and a recognition of local education, Louis Jadin, ‘Les survivances chrétiennes au Congo au XIXe siècle’, Études d'histoire africaine 1 (1970): 137–85.

[5] It is not mentioned at all in his seminal work, Thompson, Flash of the Spirit in the nearly 100-page section dealing with Kongo and its influence in Vodou, nor in Face of the Gods.

[6] Erwan Dianteill, ‘Kongo à Cuba: Transformations d'une religion africaine', Archives de Sciences Sociales de Religion 117 (2002): 59–80.

[7] Todd Ochoa, Society of the Dead: Quita Manaquita and Palo Praise in Cuba (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), pp. 8–10. Wyatt MacGaffey's work, especially Religion and Society in Central Africa: The BaKongo of Lower Zaire (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1986) is a favorite.

[8] Thiago Sapede, Muana Congo, Muana Nzambi a Mpungu: Poder e Catolicismo no reino do Congo pós-restauração (1769–1795) (São Paulo: Alameda, 2014) is the first book length study of Christianity in the later period of Kongo's history.

[9] John Thornton, ‘Afro-Christian Syncretism in the Kingdom of Kongo', Journal of African History 54 (2013): 53–77.

[10] Thornton, ‘Afro-Christian Syncretism'.

[11] Sapede, Muana Congo, pp. 248–57.

[12] Thornton, ‘Afro-Christian Syncretism', for the details of the struggle, but a perspective that sees the Capuchin mission as central to Kongo Christianity, see Saccardo, Congo e Angola.

[13] John Thornton, The Kongolese Saint Anthony: D Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, 1684–1706 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

[14] Rafael Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem ao Congo’, Academia das Cienças de Lisboa, MS Vermelho 396, pp. 32–4, 183–5 (transcription by Arlindo Carreira, 2007 at http://www.arlindo-correia.com/161007.html) which marks the pagination of the original MS.

[15] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem ao Congo', pp. 110–4.

[16] Raimondo da Dicomano, ‘Informazione' (1798), pp. 1–2. The text exists in both the Italian original and a Portuguese translation made at the same time. For an edition of both, see the transcription of Arlindo Carreira, 2010 (http://www.arlindo-correia.com/121208.html).

[17] ‘Il Stato in cui si trova il Regno di Congo', September 22, 1820, in Teobaldo Filesi, ‘L'epilogo della ‘Missio Antiqua’ dei cappuccini nel regno de Congo (1800–1835)’, Euntes Docete 23 (1970), pp. 433–4.

[18] Among the first was Domingos Pereira da Silva Sardinha in 1854, who, according to King Henrique II of Kongo, had performed his duties of administering the sacraments with ‘all the necessary prudence', Henrique II to Vicar General of Angola, December 14, 1855, Boletim Oficial de Angola, 540 (1856).

[19] Biblioteca d'Ajuda, Lisbon, Códice 54/XIII/32 n° 9, Francisco de Salles Gusmão to the King, October 27, 1856.

[20] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem ao Congo’, pp. 110–4.

[21] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7 (of manuscript).

[22] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 39, 69, 276.

[23] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagen', p. 217 (thanks to Thiago Sapede for this reference).

[24] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem’, pp. 32–4, 1835.

[25] For a thorough study of these religious artefacts and their meaning, see Cécile Fromont, The Art of Conversion: Christian Visual Culture in the Kingdom of Kongo (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

[26] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', p. 78.

[27] APF Congo 5, fols. 298–298v (Rosario dal Parco) ‘Informazione 1760' A French translation is found in Louis Jadin, ‘Aperçu de la situation du Congo, et rite d’élection des rois en 1775, d'après le P. Cherubino da Savona, missionaire de 1759 à 1774', Bulletin de l'Institut Historique Belge de Rome 35 (1963): 347–419 (marking foliation of original MS).

[28] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 180–4.

[29] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', p. 53.

[30] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 63–4; see also 87 for another noble as Captain of Church; 136 crowds at Mapinda.

[31] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7.

[32] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', p. 196.

[33] Bernard Clist et alia, ‘The Elusive Archeology of Kongo Urbanism, the Case of Kindoki, Mbanza Nsundi (Lower Congo, DRC)’, African Archaeological Review 32 (2014) 369–412 and Charlotte Verhaeghe, ‘Funeraire rituelen en het Kongo Konigrijk: De betekenis van de schelp- en glaskralen en de begraafplaats van Kindoki, Mbanza Nsundi, Neder-Kongo' (MA thesis, University of Ghent, 2014), pp. 44–50.

[34] ‘Il Stato in cui si trova il Regno di Congo', September 22, 1820, in Filesi, ‘Epilogo’, pp. 433–4.

[35] ‘O Congo em 1845: Roteiro da viagem ao Reino de Congo por Major A. J. Castro … ’, Boletim de Sociedade de Geographia de Lisboa II series, 2 (1880), pp. 53–67. The orthographic irregularity reflects the actual pronunciation of these terms in the São Salvador region (the Sansala dialect).

[36] Alfredo de Sarmento, Os sertões d'Africa (Apontamentos do viagem) (Lisbon: Artur da Silva, 1880), p. 49 and Adolf Bastian, Ein Besuch in San Salvador: Der Hauptstadt des Königreichs Congo (Bremen: Heinrich Strack, 1859), pp. 61–2.

[37] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 102–3 and da Firenze, ‘Relazione', pp. 420–1.

[38] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', p. 137.

[39] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 180–4.

[40] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7.

[41] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 32–4; da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7; Zanobio Maria da Firenze, ‘Relazione della Stato in cui si trovassi autalmente il Regno di Congo … 1814’, July 10, 1816, in Filesi, ‘Epilogo’, pp. 420–1.

[42] Archivio ‘De Propaganda Fide' (Rome) Acta 1758, ff 213–9, no. 16, Relazione di Rosario dal Parco, July 31, 1758. These large numbers were not simply priests catching up on people who had not been baptized for a long time, as personnel staffing and statistics are found from 1752 onward; but the priests did not cover the whole country every year, so many priests would baptize babies all under age two or three.

[43] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 63–4; see also 87 for another noble as Captain of Church; 136 crowds at Mapinda.

[44] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7.

[45] da Firenze, ‘Relazione', pp. 420–1.

[46] ‘Il Stato in cui si trova il Regno di Congo', September 22, 1820, in Filesi, ‘Epilogo’, pp. 433–4.

[47] Francisco das Necessidades, Report, March 15, 1845, in Arquivo do Archibispado de Angola, Correspondência de Congo, 1845–1892, cited in François Bontinck, ‘Notes complimentaire sur Dom Nicolau Agua Rosada e Sardonia’, African Historical Studies 2 (1969): 105, n. 6. Unfortunately, no researchers have been allowed to work in this section of the archive for many years and so the actual text is not available.

[48] Report of November 13, 1856 in António Brásio, ‘Monumenta Missionalia Africana’, Portugal em Africa 50 (1952), pp. 114–7.

[49] Biblioteca d'Ajuda, Lisbon 54/XIII/32 n° 9, Francisco de Salles Gusmão to the King, de Outubro de 27, 1856.

[50] Da Cruz, entry of October 8 and 25 on the problems of baptizing people.

[51] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', is the first to describe this process; for more detail see Bastian, Besuch.

[52] David Eltis, An Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

[53] For a recent discussion of names and nomenclature, see Jésus Guanche, Africanía y etnicidad en Cuba (los componentes étnicos africanos y sus múltiples demoninaciones (Havana: Editoria de Ciencias Sociales, 2008). As we shall see, a number of other subdivisions also derived from the kingdom like the Musolongos, Batas and others.

[54] John Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Formation of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), for Cuba in particular, Matt Childs, ‘Recreating African Identities in Cuba', in The Black Urban Atlantic in the Era of the Slave Trade, eds. Jorge Cañizares-Esquerra, Matt Childs, and James Sidbury (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), pp. 85–100.

[55] Robert Jameson, Letters from Havana in the Year 1820 … (London: John Miller, 1821), pp. 20–2 (from letter II).

[56] Fernando Ortiz, Hampa Afro-Cubana. Los Negros Brujos (Havana: Liberia de F. Fé, 1906), pp. 81–5; and further developed in ‘Los Cabildos Afrocubanos', in Ensayos Etnograficos, eds. Miguel Barnet and Angel Fernández (Havana: Editoriales Sociales, 1984 [originally published 1921]), pp. 12–34; for a more recent statement based on more research, Matt Childs, The 1812 Aponte Rebellion and the Struggle Against Atlantic Slavery (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), pp. 209–45 and María del Carmen Barcia Zequeira, Andrés Rodríguez Reyes, and Milagros Niebla Delgado, Del cabildo de “nación” a la casa de santo (Havana: Fundación Fernando Ortiz, 2012).

[57] For example, the now famous community of Pindar del Rio, see Natalia Bolívar Arostegui, Ta Makuende Yaya y las Reglas de Palo Monte: Mayombe, brillumba, kimbisa, shamalongo (Havana: Ediciones UNION, 1998).

[58] Childs, Aponte Rebellion, pp. 209–12; Jane Landers, ‘Catholic Conspirators: Religious Rebels in Nineteenth Century Cuba', Slavery and Abolition 36 (2015): 495–520.

[59] Brown, Santería Enthroned, pp. 62–112; María del Carmen Barcia, Los ilustres apellidos: Negros en la Habana colonial (Havana: Oficina del Historiador de la Ciudad, 2008), pp. 45–151; Barcia, Rodríguez Reyes, and Niebla Delgado, Del Cabildo which carefully demolishes the earlier theses of Fernando Ortiz and others that the cabildos grew out of the brotherhoods.

[60] This group must have split or been replaced by another, for a property dispute in the Congos Loangos relates to their foundation in 1776, Archivo Nacional de Cuba (ANC) Escribanía Valerio-Ramirez (VR) legajo 698, no. 10.205.

[61] Barcia, Iustres Apellidos, pp. 45–151.

[62] Barcia, Ilustres Apellidos.

[63] del Carmen Barcia Zequeira, Rodríguez Reyes, and Niebla Delgado, Del cabildo, pp. 12–9.

[64] Fernando Ortiz, ‘Los Cabildos Afrocubanos', in Ensayos Etnograficos, eds. Miguel Barnet and Angel Fernández (Havana: Ediciones Ciencas Sociales, 1984 [originally published 1921]), p. 13, citing documents in El Curioso Americano, 1899, p. 73.

[65] Proclama que en un cabildo de negros congos de la ciudad de La Habana, prononció por su Presidente Rey Siliman Mofundi Siliman … (Havana: np, 1808); for the claim of superiority, drawn from an ambiguous statement that he was ‘more black that you others’, see Brown, Santería Enthroned, pp. 25–7 and 311, footnotes 4 and 6. For political context, see Ada Ferrer, Freedom's Mirror: Cuba and Haiti in the Age of Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), pp. 247–9.

[66] Fredrika Bremer, Hemmen i den Nya Världen, 2nd ed., Vol. 3 (Stockholm: Tidens forläg, 1854), p. 142 (English translation as The Homes of the New World: Impressions of America, Vol. 2 (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1853), p. 322) Her host's name is given in the original and obscured in the translation as ‘C—'.

[67] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, pp. 146–8 (Homes Vol. 2, pp. 325–8).

[68] Henri Dumont, Antropologia y patologia comparadas de los Negros escalvos, 1876, trans. Israel Castellanos (Havana: Molina, 1922), p. 38.

[69] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, pp. 172–4 (Homes Vol. 2, pp. 348–9).

[70] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, p. 213 (Homes Vol. 2, p. 383).

[71] Esteban Pichardo, Diccionario provincial de voces Cubanas (Matanzas: Imprenta de la Real Marina, 1836), p. 72. Musundi may refer to Kongo's northern province of Nsundi, though the match is not exact since the nasal ‘n' is not incorporated into it, musundi might also mean ‘excellent', as the Virgin Mary was called ‘Musundi Madia' in the Kongo catechism meaning exactly this.

[72] It is possible that Bremer attended the dance of another Cabildo of Congos Reales, who were in the process of declaring their insolvency in 1851, ANC Escrabanía Joaquin Trujillo (JT) leg 84, no. 12, 1851; for a 1867 dispute, see the property case involving them in ANC VR leg. 393, no. 5875; other mentions of cabildos of this name including the group from 1865–1871 in Carmen Barcia, Ilustres apellidos, p. 408. For the 1880s mentions, see Archivio Historico de la Provincia de Matanzas (henceforward AHPM), Religiones Africanas, leg 1, no. 30, July 7, 1882; no. 65, January 9, 1898 and no. 31, July 31, 1886.

[73] Fondo Fernando Ortiz, Institute de Linguistica y Literatura, Havana, 5.

[74] ANC Escibanía d'Daumas (ED) leg 917, no. 6. (foliation uncertain, very deteriorated document).

[75] António de Oliveira de Cadornega, História das guerras angolanas (1680–81 ), eds. Matias de Delgado and da Cunha, Vol. 3 (Lisbon: Agência Geral do Ultramar, 1940–1942, reprinted 1972), p. 3, 193. In July 2011, I drove through all three dialect zones, confirmed some of the differences by hearing them spoken and by speaking with people about these differences. My thanks to Father Gabriele Bortolami, OFMCap for driving, interacting with people, impromptu language updates and occasional lessons in the etiquette of dialect use in northern Angola.

[76] Cherubino da Savona, ‘Breve ragguaglio del Congo … ’, fols. 41v–44v, published with original foliation marked in Carlo Toso, ed., ‘Relazioni inedite di P. Cherubino Cassinis da Savona sul ‘Regno del Congo e sue Missioni’, L'Italia Francescana 45 (1974): 135–214. The foliation of the original is also marked in the French translation, found in Jadin, ‘Aperçu de la situation au Congo … '

[77] ANC ED, leg 494, no. 1, fols 96–97. This text was included in papers dealing with another dispute in 1827–1828 and in 1832–1836.

[78] ANC ED, leg 548, no. 11, fol. 9–9v; José Pacheco, January 21, 1806; ANC ED, leg. 660, no. 8, fols. 1–4; Pedro José Santa Cruz (a request for its own capataz) 1806; for the later dispute ANC ED leg 494, no. 1.

[79] ANC ED, leg 660, no. 8, fol. 4.

[80] ANC JT, leg. 84, no. 13 passim, 1851.

[81] AHPM, Religiones Africanas, leg 1, no. 30, July 7, 1882.

[82] AHPM, Religiones Africanas, leg 1, no. 65, January 9, 1898.

[83] AHPM, Religiones Africanas, leg 1, no. 31, July 31, 1886.

[84] Brown, Santería Enthroned, pp. 55–61 and Barcia Zequeira, Rodríguez Reyes, and Delgado, Cabildo de nación.

[85] Childs, Aponte Rebellion, p. 112 and ‘Identity', p. 91.

[86] Consider the temporal range of inquisition cases cited in Tania Chappi, Demonios en La Habana: Episodios de la Inquisición en Cuba (Havana: Oficinia del Hisoriador de la Ciudad, 2001). For an example of the sort of persecution the Inquisition could do, and the sort of information that can be obtained from their records, see James Sweet's study of slave religious life in Brazil, Recreating Africa.

[87] Jameson, Letters, pp. 20–2.

[88] See the transcript of his interview published in Henry Lovejoy, ‘Old Oyo Influences on the Transformation of Lucumí Identity in Colonial Cuba' (PhD diss., UCLA, 2012), pp. 230–46.

[89] Aisha Finch, Rethinking Slave Rebellion in Cuba: La Escalera and the Insurgencies of 1841–44 (Chapel Hill: North Carolina Press, 2015), pp. 199–220. Finch attributes most of the activities in these cases to the non-Christian part of Kongo religion, or an early form of Palo Mayombe; see also Miguel Sabater, ‘La conspiración de La Escalera: Otra vuelta de la tuerca', Boletín del Archivo Nacional 12 (2000): 23–33 (with quotations from trial records).

[90] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, p. 213 (Homes Vol. 2, p. 383).

[91] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, pp. 211–3 (Homes Vol. 2, pp. 379–83).

[92] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 26, citing late eighteenth- and nineteenth-century sources.

[93] Abiel Abbott, Letters Written in the Interior of Cuba … (Boston, MA: Bowles and Dearborn, 1829), pp. 15–7.

[94] Cabrera did not employ any orthography of contemporary Kikongo in her day, but it is not at all difficult to recognize her ear for that language, which she did not speak, and most quotations she provided are readily intelligible.

[95] Institute de Linguistica y Literatura, Havana, Fondo Fernando Ortiz, 5. This list, written in a different hand than Ortiz’, one that was shakier with large letters, on fragile aged paper (perhaps school paper) was, I believe, compiled by a literate person who was a native speaker of the language, based on his use of Kikongo grammatical forms (use of verb conjugations and class concords in particular).

[96] Armin Schwegler, ‘On the (Sensational) Survival of Kikongo in Twentieth Century Cuba', Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages 15 (2000): 159–65; Jesús Fuentes Guerra, La Regla de Palo Monte: Un acercamiento a la Bantuidad Cubana (Havana: Iberoamericana Vervuert, 2012) (neither Schwegler nor Fuentes Guerra had access to Puyo's vocabulary in Ortiz’ documentation, the contention of its identity with Kikongo is my own). It seems likely that both Cabrera's and Ortiz’ vocabularies were collected probably from old native speakers, who entered Cuba at the end of the slave trade.

[97] For example, the class marker ki in the southern dialect is –ci in the north; use of ‘l' versus ‘d' would be another difference. The northern dialect is well attested in dictionaries of the French mission to Loango and Kakongo in the 1770s, compared with seventeenth- and nineteenth-century dictionaries of the southern dialects. I have also heard these differences myself in Angola.

[98] Fernando Ortiz, Hampa Afro-Cubana. Los Negros Esclavos (Havana: Bimestre Habana, 1916), pp. 25, 32 (clearly, testimony from the same informant).

[99] Ortiz, Negros Esclavos, p. 34. The term ‘Totila', clearly derived from the Kikongo ntotela meaning ‘king'. The word is first attested in the Kikongo dictionary of 1648, as meaning ‘King'. In 1901, King Pedro VI of Kongo, writing in Kikongo, styled himself ‘Ntinu Ntotela NeKongo' Archives of the Baptist Missionary Society (Regents’ Park College, Oxford) A 124 (both ntinu and ntotela can be glossed as ‘king').

[100] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 15.

[101] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 109. Cabrera, for her part, then told him of Nzinga a Nkuwu's baptism in 1491, presumably from one of the historical accounts she had read.

[102] On the assertions of Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita, see Thornton, Kongolese Saint Anthony; on the representation of Christ as an Kongolese, Fromont, Art of Conversion.

[103] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 93.

[104] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 58.

[105] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 59.

[106] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 14.

[107] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 19.

[108] The problem was apparent to Lydia Cabrera in her study of Palo, El Regla de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe (Miami: Ediciones Universal, 1979), pp. 120–30, as one can see from the defensive tone of her informants, probably speaking with her post-1960 experience (this is not seen as a problem in her earlier publication, El Monte (Havana, 1954)).

[109] Cabrera, Vocabulario, p. 123.

[110] Cabrera, Monte, pp. 119–23 passim (here, often used in the context of witchcraft); Reglas de Congo, pp. 24–5. In W. Holman Bentley, Dictionary and Grammar of the Kongo Language (London: Kegan Paul, 1887), p. 361, which relates to the Kinsansala dialect (the most likely associated with Christianity) in the 1880s, mvumbi meant simply the corpse of a dead person; in the 1648 dictionary ‘spirits' was rendered as ‘mioio mia mvumbi' (or souls of corpses).

[111] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 24. In Kikongo, mvumbi means a corpse, the lifeless remains of a dead person, and the name of an ancestor would usually have been nkulu, though this usage would still make sense in Kikongo.

[112] See John Thornton, ‘Central African Names and African American Naming Patterns', William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd Series, 50 (1993): 727–42.

[113] The denunciation of the first tooth ceremony is only attested in the general complaints of the Capuchins in the 1650s, written by Serafino da Cortona.

[114] ‘Kisi malongo' appears to be ‘nkisi malongo'. A more likely way to say ‘the teaching of nkisi' would be ‘malongo ma nkisi', so the word order puzzles me. However, word order in Kikongo is flexible and should the speaker wish to emphasize the teaching spiritual part, it might be feasible to use this order.

[115] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 24. My translation of the phrase ‘nganga la musi' assumes that the speaker has only partial command of Kikongo grammar and would be ‘nganga a mu nsi' The same informant used the term kisi malongo, and perhaps as a Cuban-born person was not secure in the language.

[116] Cabrera, Regla de Congo, p. 23.

[117] Institute de Linguistica y Literatura, Havana, Fondo Fernando Ortiz, 5.

#The Kingdom of Kongo and Palo Mayombe: Reflections on an African-American Religion#Palo Mayombe#ATR#African Traditional Religions#Kongo#Reglas De congo#Nkisi#Kikongo

0 notes