#Juan Huarte

Text

Sumillera, R. G. (2020). Political Medicine in Early Modern Spain, or How Physicians Counsel the King. Sixteenth Century Journal, 51(2).

I'm not so sure about the medical metaphor used by natural philosophers - or, more precisely, medical humanists - in the late 16th century. I'm still looking into it. For now, I believe they are first and foremost physicians or philosophers. This represents their (social) identity. Then, of course they can counsel the princes if given the opportunity, using the metaphor that compares the country (in need of remedies) to a (unbalanced) body.

0 notes

Text

La Ergonomía: Antecedentes y Orígenes

La Ergonomía: Antecedentes y Orígenes

Antecedentes:

Los registros históricos indican que existen trabajos que se consideran como las primeras investigaciones científicas que sentaron la bases para el estudio de la ergonomía. Entre ellos destaca el trabajo del científico español: Juan Huarte de San Juan (1530-1592) y su obra Examen de Ingenios para la Ciencia en 1575, donde relaciona las capacidades individuales del ingenio o la…

View On WordPress

#Elton Mayo#Ergonomía#Ergonomics Research Society#Estudio de Movimientos#Estudio de tiempos#Examen de Ingenios para la Ciencia#Frederick Taylor#Gilbreth#Gustav Theodor Fechner#Human Research Society#Juan Huarte de San Juan#la Ciencia del Trabajo Basada en Verdades Tomadas de la Naturaleza#Wilhelm Maximiliam Wundt#Wojciech Bogumil Jastrzebowski

0 notes

Text

Navegamos en busca de nosotros mismos

Isidro Huarte n° 108, Centro Histórico.

Morelia, Michoacán, Mex.

Juan Fuerte, 2016.

6.20 × 2.15 mts.

#Juan Fuerte#Pintor Urbano#Muralismo#street art#urban art#murales#Morelia#Michoacán#mural#protesta#antropomorfo#digitomorfo#dactiliforme#fauna#manos#mariposa#monarca#peces#humanos#maíz#regional

0 notes

Text

🚨 WEDNESDAY MATCHES RESULTS ✅

Wednesday August 30

👉 CHAMPIONS LEAGUE - QUALIFICATION

FT. AEK Athens 1 - 2 Royal Antwerp

FT. FC Copenhagen 1 - 1 Rakow Czestochowa

FT. PSV Eindhoven 5 - 1 Rangers

👉 🏴 ENGLAND - EFL CUP ROUND 2

FT. Chelsea 2 - 1 AFC Wimbledon

FT. Harrogate 0 - 8 Blackburn Rovers

FT. Nottingham Forest 0 - 1 Burnley

AP. Sheffield United 0 - 0 Lincoln City

FT. Doncaster Rovers 1 - 2 Everton

👉 🇮🇹 ITALY - SERIE B

FT. Bari 1 - 1 Cittadella

FT. Catanzaro 3 - 0 Spezia

FT. Sampdoria 1 - 2 Venezia

FT. Ternana 0 - 1 Cremonese

👉 🇦🇷 ARGENTINA - CUP

AP. Talleres 2 - 2 Colon

FT. Argentinos Juniors 0 - 1 San Martin San Juan

👉 JAPAN - EMPEROR'S CUP

AP. Albirex Niigata 2 - 2 Kawasaki Frontale

FT. Avispa Fukuoka 3 - 1 Shonan Bellmare

FT. Kashiwa Reysol 2 - 0 Nagoya Grampus Eight

AP. Roasso Kumamoto 1 - 1 Vissel Kobe

👉 🇺🇲 COPA SUDAMERICANA - QUARTER FINALS

AP. Estudiantes de la Plata 1 - 0 Corinthians

👉 POLAND - EKSTRAKLASA

FT. Pogon Szczecin 0 - 2 Slask Wroclaw

👉 FINLAND - VEIKKAUSLIIGA

FT. FC Lahti 1 - 2 FC Inter Turku

👉 SOUTH AFRICA - PREMIER LEAGUE

FT. Polokwane City 0 - 2 Mamelodi Sundowns FC

FT. Chippa United 2 - 3 Royal AM

FT. Moroka Swallows 3 - 1 Cape Town Spurs

FT. Richards Bay 1 - 1 Sekhukhune United

FT. Stellenbosch FC 0 - 2 Kaizer Chiefs

👉 CLUB FRIENDLIES - CLUB FRIENDLIES

FT. CD Varea 2 - 2 Club Deportivo Huarte

FT. Xerez Deportivo FC 1 - 0 AD Ceuta FC

FT. CD Galapagar 1 - 1 Las Rozas CF

👉 INTERNATIONAL - CENTRAL AMERICAN CUP: GROUP A

FT. C.S. Cartagines 2 - 2 UD Universitario

FT. Deportivo Saprissa 5 - 0 Coban Imperial

🙏 👉 FOLLOW US MyScores

#clubfriendlies#SAPremierLeague#veikkausliiga#ekstraklasa#Sudamericana#emperorscup#argentinacup#SERIAB#EFLCup#uefachampionsleague#CentraAmericanCup

0 notes

Text

La contemplación de la Pasión en Teresa de Jesús y el Siglo de Oro de la espiritualidad en la Monarquía Hispánica

La contemplación de la Pasión en Teresa de Jesús

La revista Huarte de San Juan de la Universidad de Navarra publica en su número de junio de este año (vol. 29/2022) un artículo titulado La contemplación de la Pasión en Teresa de Jesús y el Siglo de Oro de la espiritualidad en la Monarquía Hispánica . Su autor es Javier Burrieza Sánchez, profesor de Historia Moderna de la Universidad de Valladolid y autor de numerosas publicaciones sobre la…

View On WordPress

0 notes

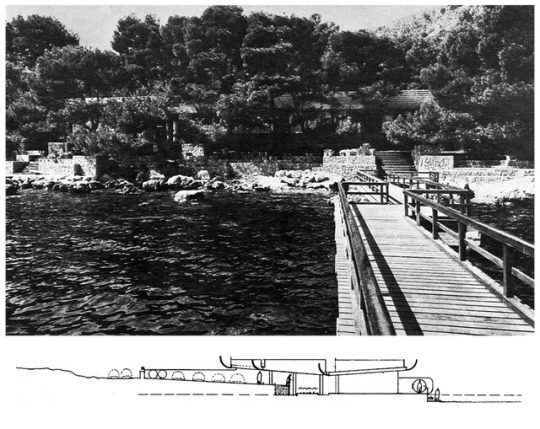

Photo

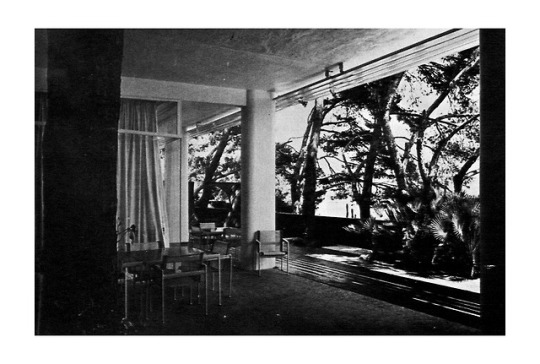

Casa Juan Huarte, house extension

Formentor, Islas Baleares, Spain; 1969

Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza

see map | more information

via "COAM Arquitectura" 154 (1971)

#architecture#arquitectura#architektur#architettura#francisco javier sáenz de oiza#francisco javier saenz de oiza#sáenz de oiza#saenz de oiza#casa juan huarte#casa#house#haus#wohnhaus#formentor#islas baleares#balearic islands#espana#spain#spanish architecture

73 notes

·

View notes

Photo

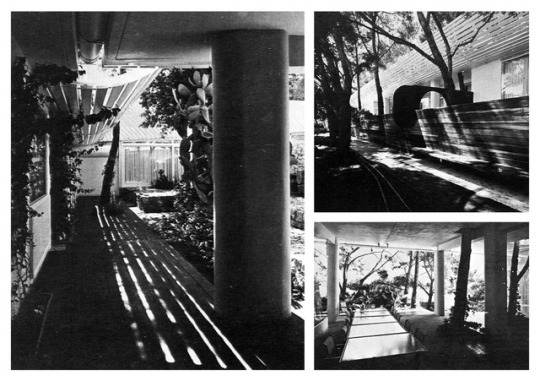

Casa Juan Huarte (1969) in Formentor on the Balearic Island of Mallorca, Spain, by Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza

148 notes

·

View notes

Photo

‘LAS PILDORAS DE MI NOVIO’ Interview | Jaime Camil & Sandra Echeverría on Must-Have Travel Items Thanks to Lionsgate/Pantelion Films and in celebration of their new film, LAS PILDORAS DE MI NOVIO (MY BOYFRIEND'S MEDS), I had the opportunity to interview its lovely stars, Jaime Camil (JANE THE VIRGIN, THE SECRET LIFE OF PETS) and Sandra Echeverría (SAVAGES)

#Ana Belena#Brian Baumgartner#Daniel Tovar#Jaime Camil#James Maslow#Juan Soler#Kevin Holt#Las Pildoras De Mi Novio#Monica Huarte#Sandra Echeverría

0 notes

Text

Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza – Casa Juan Huarte

1969, Formentor (ES)

via #1, #2

167 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women like me have been keeping a secret. It’s a secret so shameful that it’s hidden from friends and lovers, so dark that vast amounts of time and money are spent hiding it. It’s not a crime we have committed, it’s a curse: facial hair.

What can be dismissed as trivial is a source of deep anxiety for many women, but that’s what female facial hair is; a series of contradictions. It’s something that’s common yet considered abnormal, natural for one gender and freakish for another. The reality isn’t quite so clearcut. Merran Toerien, who wrote her PhD on the removal of female body hair, explained “biologically the boundary lines on body hair between masculinity and femininity are much more blurred than we make them seem”.

About one in 14 women have hirsutism, a condition where “excessive” hair appears in a male pattern on women’s bodies. But plenty more women who don’t come close to that benchmark of “excessive” still feel deeply uncomfortable about their body hair. If you’re unsure whether your hair growth qualifies as “excessive” for a woman, there’s a measurement tool that some men have developed for you.

In 1961, an endocrinologist named Dr David Ferriman and a graduate student published a study on the “clinical assessment of body hair growth in women”. More specifically, they were interested in terminal hairs (ones that are coarser, darker and at least 0.5cm/0.2 inches in length) rather than the fine vellus hairs. The men looked at 11 body areas on women, rating the hair from zero (no hairs) to four (extensive hairs). The Ferriman-Gallwey scale was born.

It has since been simplified, scoring just nine body areas (upper lip, chin, chest, upper stomach, lower stomach, upper arms, upper legs, upper back and lower back). The total score is then added up – less than eight is considered normal, a score of eight to 15 indicates mild hirsutism and a score greater than 15 moderate or severe hirsutism.

Most women who live with facial hair don’t refer to the Ferriman-Gallwey scale before deciding they have a problem. Since starting to research hirsutism, I’ve received over a hundred emails from women describing their experiences discovering, and living with, facial hair. Their stories loudly echo one another.

Because terminal hairs start to appear on girls around the age of eight, the experiences start young. Alicia, 38, in Indiana wrote, “kids in my class would be like, ‘Haha look at this gorilla!’”, Lara was nicknamed “monkey” by her classmates while Mina in San Diego was called “sasquatch”. For some girls, this bullying (more often by boys) was their first realization that they had facial hair and that the facial hair was somehow “wrong”. Next, came efforts to “fix” themselves.

Génesis, a 24-year-old woman described her first memories of hair removal. “In fourth grade, a boy called me a werewolf when he saw my arm hairs and upper lip hairs … I cried to my mom about it … she bleached my lower legs, my arms, my back, my upper lip and part of my cheeks to diminish my growing sideburns. I remember it itched and burned.”

After those first attempts come many, many more – each with their own investment in time, money and physical pain. The removal doesn’t just make unwanted hair go away, it raises a whole new set of problems, particularly for women of color. Non-white skin is more likely to scar as a result of trying to remove hair.

"Instead of reading or finishing homework on the car drives to school growing up, I would spend the entire length of the drive obsessively plucking and threading my mustache. Every day." – Rona K Akbari, 21, Brooklyn

On average, women with facial hair spend 104 minutes a week managing it, according to a 2006 British study. Two-thirds of the women in the study said they continually check their facial hair in mirrors and three-quarters said they continually check by touching it.

The study found facial hair takes an emotional toll. Forty percent said they felt uncomfortable in social situations, 75% reported clinical levels of anxiety. Overall, they said that they had a good quality of life, but tended to give low scores when it came to their social lives and relationships. All of this pain despite the fact that, for the most part, women’s facial hair is entirely normal.

"If I know I have visible facial hair, I’m much more reserved in social situations. I try to cover it up by placing my hand on my chin or over my mouth. And I’m thinking about it constantly." – Ashley D’Arcy, 26

"Meanwhile, my 95-year-old demented, deaf and blind Italian aunt sits in a nursing home, and whenever I visit, she points to and rubs her chin, which is her way of communicating to take care of the hair situation. That’s how I know she’s still in there and she cares. I hope someone returns the favor in 40 years." – Julia, 54

There are, however, some medical conditions which can cause moderate or severe hirsutism, the most likely of which is polycystic ovary syndrome, or PCOS, which accounts for 72-82% of all cases. PCOS is a hormonal disorder affecting between eight and 20% of women worldwide. There are other causes too, such as idiopathic hyperandrogenemia, a condition where women have excessive levels of male hormones like testosterone, which explains another 6-15% of cases.

But many women who don’t have hirsutism, who don’t have any medical condition whatsoever, consider their hairs “excessive” all the same. And that’s much more likely if you’re a woman of color.

The original Ferriman-Gallwey study, like so much western medical research at the time, produced findings that might not apply to women of color (the averages were based on evaluations of 60 white women). More recent research has suggested that was a big flaw, because race does make a big difference to the chances that a woman will have facial hair.

In 2014, researchers looked at high-resolution photos of 2,895 women’s faces. They found that, on average, the white women had less hair than any other race and Asian women had the most. But ethnicity mattered too – for example, the white Italian women in the study had more hair than the white British women.

"But more than a gender thing, for me my hair was about race/ethnicity. My hairiness really solidified how different I was from my peers. I grew up in the suburbs of Dallas. And although my school was pretty diverse, the dominant beauty norm was to be blonde and white." – Mitra Kaboli, 30, Brooklyn

These numbers might be helpful to women like Melissa who said her facial hair meant “I felt inferior, I was a ‘dirty ethnic’ girl”.

But giving reassurance to ethnic minorities probably isn’t why this research was undertaken. The study was funded by Procter & Gamble, the consumer goods company worth $230bnwhich sells, among other things, razors for women. They know that female hair removal is big business.

Over the years, as women showed more of our bodies – as stockings became sheer and sleeves became short, there was pressure for these new exposed parts to be hairless. Beginning in 1915, advertisements in magazines like Harper’s Bazaar began referring to hair removal for women. Last year, the hair removal industry in the US alone was valued at $990m. The business model only works if we hate our hair and want to remove it or render it invisible with bleach (a norm just as unrealistic as hairlessness – brown women rarely have blonde hair).

When did we sign up to an ideal of female hairlessness? The short answer is: women have hated our facial hair for as long as men have been studying it. In 1575, the Spanish physician Juan Huarte wrote: “Of course, the woman who has much body and facial hair (being of a more hot and dry nature) is also intelligent but disagreeable and argumentative, muscular, ugly, has a deep voice and frequent infertility problems.”

These signposts are strictest when it comes to our faces, and they extend beyond gender to sexuality too. According to Huarte, masculine women, feminine men and homosexuals were originally supposed to be born of the opposite sex. Facial hair is one important way to understand these distinctions between “normal” and “abnormal”, and then police those boundaries.

Scientists have turned their sexist and homophobic expectations of body hair to racist ones, too. After Darwin’s 1871 book Descent of Man was published, male scientists began to obsess over racial hair types as an indication of primitiveness. One study, published in 1893, looked for insanity in 271 white women and found that women who were insane were more likely to have facial hair, resembling those of the “inferior races”.

These aren’t separate ideas because race and gender overlap – black is portrayed in mass media as a masculine race, Asian as feminine. Ashley Reese, 27, wrote “part of my self-consciousness about my facial hair might also tie into some ridiculous internalized racism about black women being less inherently feminine”. While Katherine Parker, 44, wrote, “It makes me feel very confused about my gender.”

Some women are pushing back. Queer women – those who are questioning heterosexual and cisgender norms – are already thinking outside of the framework that shames female facial hair. Melanie, a 28-year-old woman in Chicago explained that as a queer woman “there is less of a prescription for what I should embody as a woman, what attraction between my partner and I looks like, which has helped immensely in coming to terms with my facial hair”.

Social media accounts like hirsute and cute, happy and hairy and activists like Harnaam Kaur are resisting these norms too, by shamelessly sharing images of hairy female bodies. And even women who aren’t rejecting these standards outright, feel deeply ambivalent about them. “I understand, on a rational level, how inherently misogynistic it is to expect women to be constantly ripping hair out of themselves, hair that grows naturally, wrote one woman who, like many I heard from, asked to remain anonymous. “But I can’t bring myself to accept it and let it grow.”

Another wrote: “It’s one thing to be a little heavy, or short, or both. But facial hair? That’s pushing it.”

I’m not about to judge any woman for removing her facial hair. Despite knowing that I don’t need “help”, I still go to see a beauty “therapist” each month. I pay huge sums so she can zap me with a laser that damages my hair follicles. I’ve signed up for a solution, even though I know that the problem doesn’t really exist. I lie there wincing with each shock as she asks me about my weekend and says “Honey, are you sure you don’t want me to do your arms too? They’re very hairy.”

805 notes

·

View notes

Text

Keitt, A. (2013). The devil in the Old World: anti-superstition literature, medical humanism and preternatural philosophy in early modern Spain. Angels, demons and the New World, 15-39.

When I read Examen de ingenios para las ciencias written by Juan Huarte de San Juan (1529-1588) it strikes me that he seems to have absorbed the idea of elevating soul (& poetry as a divine frenzy) proposed by Marsilio Ficino. In Huarte’s theory the faculty of imagination is related to the quality heat in Galen’s temperament theory. It is heat that brings to imagination a feature of promptnesses, and establishes a direct link between imagination and (artistic) creation.

In page 109 of the English version Huarte says: “Three degrees of heat, and this quality so extended (as we have before expressed) breeds an utter loss of the understanding.”

…which, is the key to poetry writing. I am glad that there is a paper confirming my guess. (And as we know how much Ficino loves the concept of melancholy.)

#Juan Huarte de San Juan#Juan Huarte#Marsilio Ficino#16c Spanish Philosophy#History of Psychology#16th century#Imagination#Poetry writing#Melancholy

1 note

·

View note

Link

1 note

·

View note

Video

vimeo

Five new ways to greet people ( in times of covid-19 ) from Nice Shit Studio on Vimeo.

We, human beings are going through a very difficult time, our lives and our habits have been disrupted and we are now behaving in new ways, and taking new measures as we learn, day by day.

This project was born only a few weeks back when Coronavirus started to hit harder in Europe - and especially in our heads - as we began to understand something serious was going on.

The first thing we tried to change was how we greet people: we’re used to giving long hugs, complicated handshakes and tons of kisses, and all these started to feel somehow inappropriate and unsafe.

With the overwhelming torrent of information and (scary) news that gets to us every day, we created this little film aiming to address social distancing in a funny and positive way, with bright colours and playful characters, at least for a few seconds and creating awareness at the same time.

If we managed to get a tiny laugh out of you, we've reached our goal.

Credits:

Produced & Directed by Niceshit

Written by: Guido Lambertini & Sarah-Grace Mankarious

EP: Agusta Timotea

Art Direction & Design: Carmen Angelillo & Rodier Kidmann

Animation & Cleanup: Guido Lambertini, Rodier Kidmann, Carmen Angelillo, Ana Freitas & Juan Huarte

Music & Sound Design: Aimar Molero

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Championnat d'Argentine FAM (resultats)

Resultats de le Championnat d'Argentine FAM 2016 , un evenement qui s'est tenu les 20 et 21 aout au stade couvert des Malvinas Argentinas a Buenos Aires (Argentine). Rodrigo Cortez se proclame champion absolu dudit championnat.

Resultats du Championnat d'Argentine FAM 2016

Fitness choregraphique junior

1. Flamini Tomas (Córdoba)

Fitness choregraphique feminin

1. Medici Karina (Salta)

2. Galetto Carola (Córdoba)

Fauteuil roulant

1. Rabucci Edgardo (Buenos Aires)

Lire la suite

Cadets

1. Jara Mauricio (Buenos Aires)

Junior jusqu'a 80 kg

1. Torres Ivan (Buenos Aires)

2. Alioni Leonardo (Córdoba)

3 Gelvez Mauro (Buenos Aires)

4. Stoppini Alexis (Buenos Aires)

5. Rodríguez (Lucas)

6. Dileo Santiago (Buenos Aires)

Junior jusqu'a 90 kg

1. Barrios Vik Francisco (Chubut)

2. Cabral Martin Chaco

Junior +90 kg

1. Gutiérrez Isaícomme (Buenos Aires)

2. Perin Pablo (Córdoba)

Junior general

1. Barrios Vik Francisco (Chubut)

2. Torres Ivan (Buenos Aires)

3. Gutiérrez Isaícomme (Buenos Aires)

Master jusqu'a 70 kg

1. Ayala Carlos Misiones

2. Agüeuhía Omar (Buenos Aires)

3. Barrios Gustavo (Buenos Aires)

4. Segatori Marcelo (Buenos Aires)

5. Guedes Alejandro (Buenos Aires)

6. Caon Mario (Córdoba)

7. Redondo Pablo (Santa Fe)

Master jusqu'a 80 kg

1. Rivero Daniel (Córdoba)

2. Fontaiña Dario (Buenos Aires)

3. Vega Manuel (Chubut)

4. Galleguillo Ruben (San Juan)

5. Vidal Alejandro (San Luis)

6. Orcuño Eduardo (Buenos Aires)

7. Oyhanart Mariano (Buenos Aires)

Master jusqu'a 90 kg

1. Aravena Pablo (Neuquen)

2. Smud Mariano (Santa Fe)

3. Acuña Daniel (Buenos Aires)

4. James Darío (Buenos Aires)

5. Garcíun José (Córdoba)

6. Callejas Walter (Buenos Aires)

7. Vera Vazquez Fernando (Mendoza)

8. Bigongiardi Hugo (Buenos Aires)

Maitre +90 kg

1. Duran Daniel (Caba)

2. Arrúa Gonzalo (Buenos Aires)

3. Sabella Ariel (Buenos Aires)

4. Bracco Augusto (Buenos Aires)

Master 50 a 80 kg

1. Agüeuhía Omar (Buenos Aires)

2. González Hugo (Salta)

Maitre 50 +80 kg

1. Turchet Daniel (Terre de Feu)

2. Rivarola Andrés (Córdoba)

3. Medina José (Entre Ríos)

Maitre 60 ans

1. Sosa Dario (Santa Fe)

2. Aramburu Fernando (Buenos Aires)

3. Ayala Maximo (Buenos Aires)

Master general

1. Duran Daniel (Caba)

2. Rivero Daniel (Córdoba)

3. Aravena Pablo (Neuquen)

4. González Hugo (Salta)

5. Ayala Carlos (Misiones)

6. Sosa Dario (Santa Fe)

Bodybuilders Ladies

1. Fougereández Soledad (Caba)

2. López Ana (Córdoba)

Femmes´s Physique

1. Sanchez Erica (Buenos Aires)

2. Rodríguez Yanina (Buenos Aires)

3. Coria Aida (Córdoba)

4. Zurita Graciela (Buenos Aires)

5. Figueredo Anahi (Santiago Del Estero)

6. Andia Maria Magdalena (Mendoza)

7. Danna Elsa (Salta)

Hommes´s Physique Junior jusqu'a 1,70 Cm

1. Martínez Emanuel (Santa Fe)

2. Escudero Pablo Mendoza

Hommes´s Physique Junior +1,70 Cm

1. Koropeski Hugo (Missions)

2. Miladin Agustin (Misiones)

3. Bonggio Tomas (Entre Rios)

4. Chludil Mauricio (Buenos Aires)

5. Albinati Nicolas (Buenos Aires)

6. Guardeño Jorge (Córdoba)

7. Grenziolo Ignacio (Buenos Aires)

8. Zubiaurre Santiago (Caba)

9. Corvo Nicolas Misiones

10. Bandeira Camilo (Buenos Aires)

11. Barbieri Emiliano (Buenos Aires)

12. Schvartz Joel (Entre Rios)

Hommes´s Physique Master

1. Rodriguez Hernan (Buenos Aires)

2. Blangino Maximiliano Corboba

3. Antillon Vladimir (Buenos Aires)

4. González Claudio (Buenos Aires)

5. Vázquez Héctor Misiones

Hommes´s Physique jusqu'a 1,66 Cm

1. Mainetti Jonatan (Buenos Aires)

2. Cerrudo Jorge (Entre Rios)

Hommes´s Physique jusqu'a 1,70 Cm

1. Bitterman Gaston (Buenos Aires)

2. Navetta Diego (Buenos Aires)

3. Serafini Fernando (Buenos Aires)

4. Perez Agustin (Buenos Aires)

5. Vitali Sergio (Buenos Aires)

Hommes´s Physique Junior jusqu'a 1,74 Cm

1. Campos Javier (Buenos Aires)

2. Garcíun Cristian (Buenos Aires)

3. Miladin Agustin Misiones

4. Alejandro Perezlindo (Buenos Aires)

5. Cardascia Federico (Buenos Aires)

6. Juncos Cristian (Buenos Aires)

7. González Martin (Caba)

8. Cianca Julian (Buenos Aires)

9. Leccese Mariano (Buenos Aires)

10. Fougereández José Luis (San Luis)

11. Lopez Leandro (Buenos Aires)

12. Henoch Cesar (Rio Negro)

Hommes´s Physique Junior jusqu'a 1,78 Cm

1. Galeano Matias (Buenos Aires)

2. Decorte Daniel (Córdoba)

3. Villaruel Damian (Buenos Aires)

4. Zubiaurre Santiago (Caba)

5. Bandeira Camilo (Buenos Aires)

6. Antillon Vladimir (Buenos Aires)

7. Schvartz Joel (Entre Rios)

Hommes´s Physique Junior +1,78 Cm

1. Avancini Daniel (Córdoba)

2. De Freitas Paulo (Caba)

3. Luna Diego (Buenos Aires)

4. Mayo Leandro (Buenos Aires)

5. Guardeño Jorge (Córdoba)

6. Kim Cristian (Córdoba)

7. Wagner Sergio (Buenos Aires)

8. Lambeaux Cedric (Santa Fe)

9. Perez Cristian (Buenos Aires)

10. Vergara Santiago (Entre Rios)

11. Santin Matias Mendoza

12. Añanez Ivo (Chubut)

13. Gonzalez Ramon (Rio Negro)

Hommes en general´s Physique

1. Bitterman Gaston (Buenos Aires)

2. Koropeski Hugo Misiones

3. Avancini Daniel (Córdoba)

4. Galeano Matias (Buenos Aires)

5. Campos Javier (Buenos Aires)

6. Rodriguez Hernan (Buenos Aires)

7. Martinez Emanuel (Santa Fe)

8. Mainetti Jonatan (Buenos Aires)

Bikini junior

1. Garcia Julieta (Buenos Aires)

2. Salvai Juana (Santa Fe)

3. Silva Lara (Buenos Aires)

4. Oviedo Candela (Córdoba)

5. Basualdo Ayelen (Buenos Aires)

6. Scianca Veronica (Buenos Aires)

7. Ayala Fernanda (Córdoba)

8. Delgadillo Betsabel (Salta)

9. Bidegain Beatriz (Buenos Aires)

Bikini Master

1. Aramayo Susana Tucuman

2. Quadri Analia (Buenos Aires)

3. Gomez Pamela (Buenos Aires)

4. Gutierrez Romina (Buenos Aires)

5. Zapata Vanina (Buenos Aires)

6. Gomez Anabella (Buenos Aires)

7. Cozzi Marisol (Buenos Aires)

8. Rovetto Sabina Rosario

9. Catania Antonella Tucuman

10. Martinez Maria Eugenia Chaco

11. Betelu Mariela (Buenos Aires)

12. Vezzi Romina (Buenos Aires)

13. Canovas Jesica (Córdoba)

14. Mendoza Alejandra (Caba)

Bikini Grand Master

1. Leguizamon Silvia (Salta)

2. Matuk Ana Laura (Buenos Aires)

3. Cozzi Marisol (Buenos Aires)

4. San Justo Daniela (Buenos Aires)

5. Jessica Misiones Minadeo

6. Reggiani Romina (Neuquen)

7. Reyna Maria Angelica (Córdoba)

8. Barraza Myriam (Buenos Aires)

Bikini jusqu'a 1,60 cm

1. Bottarelli Josela (Buenos Aires)

2. Quadri Analia (Buenos Aires)

3. Briccola Romina Tucuman

4. Gomez Anabella Bsas

5. Salvai Juana (Santa Fe)

6. Scianca Veronica (Buenos Aires)

7. Cid Vanesa (Neuquen)

8. Oviedo Candela (Córdoba)

9. Martinez Maria Eugenia Chaco

Bikini jusqu'a 1,63 cm

1. Juarez Analia Formosa

2. Paz Cecilia Chaco

3. Alvarez Victoria (Córdoba)

4. Silva Lara (Buenos Aires)

5. Benitez Daiana (Buenos Aires)

6. Escudero Carla (San Luis)

Bikini jusqu'a 1,66 cm

1. Aramayo Susana Tucuman

2. Garcia Julieta (Buenos Aires)

3. Zapata Vanina (Buenos Aires)

4. Catania Antonella Tucuman

5. Vezzi Romina (Buenos Aires)

Bikini jusqu'a 1,69 cm

1. Chevreuil Luciana Tucuman

2. Gutierrez Romina (Buenos Aires)

3. Leguizamon Silvia (Salta)

4. La Forgia Lucrecia (Buenos Aires)

5. Betelu Mariela (Buenos Aires)

Bikini H +1,69 Cm

1. Degani Maria Laura (Buenos Aires)

2. Gomez Pamela (Buenos Aires)

3. Castro Natalia (Buenos Aires)

4. Reggiani Romina (Neuquen)

Maillot de bain

1. Aramayo Susana Tucuman

2. Garcia Julieta (Buenos Aires)

3. Juarez Analia (Formosa)

4. Bottarelli Josela (Buenos Aires)

5. Leguizamon Silvia (Salta)

6. Degani Maria Laura (Buenos Aires)

7. Corzo Luciana (Tucuman)

Culturisme classique junior

1. Frigerio Fabrizio (Córdoba)

2. Alvarez Abel (Córdoba)

3. Aguirre Merlach Lautaro (Corrientes)

4. Passione (Lucas) (Buenos Aires)

Musculation classique classique

1. Lagos Juan (Buenos Aires)

2. Herrero Galvez Fernando (Córdoba)

3. Mariano gauche (Buenos Aires)

Culturisme classique jusqu'a 1,71 cm

1. Lagos Juan (Buenos Aires)

2. Lopez Raul (Córdoba)

3. Echenique Eduardo (Mendoza)

4. Ramirez Andrés (Entre Ríos)

5. Zitta Alejandro (Buenos Aires)

6. Meza Rodrigo (Chaco)

7. Ayuso Alejandro (Buenos Aires)

8. Cuellar Pablo (Tucumán)

Culturisme classique jusqu'a 1,75 cm

1. Julian Walls (Córdoba)

2. Paz Lauro (Salta)

3. Sole Ignacio (Rio Negro)

4. Rodriguez Ivan (Buenos Aires)

5. Boyadjian Juan (Caba)

6. Gonzalez Sebastian (Santa Fe)

Culturisme classique jusqu'a 1,80 cm

1. Grañun Ivan (Santa Fe)

2. Anuch Pablo (Salta)

3. Ruiz Mártin (Buenos Aires)

4. Cabrera Julian (Buenos Aires)

5. Frigerio Fabrizio (Córdoba)

6. Arret Claudio (San Juan)

7. Mattos Gustavo (Buenos Aires)

8. Usseglio Emmanuel (Buenos Aires)

9. Esnaola Gabriel (Buenos Aires)

10. Contreras Santiago (Neuquen)

Culturisme classique +1.80 Cm

1. Cossi Marcos (Buenos Aires)

2. Cuellar Alvaro (Tucumán)

3. Huarte Santiago (Córdoba)

4. Pintos Miguel (Formosa)

5. Morinigo Mario (Buenos Aires)

6. Alvarez Abel (Córdoba)

7. Garcíun Braian (Buenos Aires)

8. Schmerco Daniel (Buenos Aires)

Bodybuilding classique global

1. Julian Walls (Córdoba)

2. Cossi Marcos (Buenos Aires)

3. Lagos Juan (Buenos Aires)

4. Grañun Ivan (Santa Fe)

5. Frigerio Fabrizio (Córdoba)

Bodyfitness Junior

1. Rivarola Andrea (San Luis)

Bodyfitness Master jusqu'a 1,63 Cm

1. Delgado Valeria (Salta)

2. Balli Natalia (Caba)

3. Pastre Joanna (Buenos Aires)

4. Irala Lorena (Formosa)

5. Aroca Nelida (Neuquen)

6. Zuebas Lely (Chaco)

Maitre Bodyfitness +1,63 Cm

1. Echenique Alejandra (Buenos Aires)

2. Valdez Gabriela (Santa Fe)

3. Castelli Maria Soledad (Santiago Del Estero)

4. Gonzalez Rita (Buenos Aires)

Bodyfitness Grand Master

1. Bosini Liliana (La Rioja)

2. Contreras Liliana (Córdoba)

3. Pomilio Adriana (Rio Negro)

4. Silva Sandra (Buenos Aires)

5. Erable Lilian (Tierra Del Fuego)

Bodyfitness jusqu'a 1,58 cm

1. Delgado Valeria (Salta)

2. Balli Natalia (Caba)

3. Barua Lilian (Buenos Aires)

4. Pastre Joanna (Buenos Aires)

5. Aroca Nelida (Neuquen)

6. Rivarola Andrea (San Luis)

Bodyfitness jusqu'a 1,63 Cm

1. Luciani Lorena (Buenos Aires)

2. Maldonado Natalia (Rio Negro)

3. Contreras Karina (Caba)

4. Irala Lorena (Formosa)

5. Testa Carolina (Buenos Aires)

Bodyfitness jusqu'a 1,68 cm

1. Echenique Alejandra (Buenos Aires)

2. Colonel Solana (Córdoba)

3. Manicler Laura (Chubut)

4. Coupe Juliette (Salta)

5. Valdez Gabriela (Santa Fe)

Bodyfitness +1,68 Cm

1. Danei Marina (Buenos Aires)

2. Rodríguez Cintia (Córdoba)

3. Peralta Roxana (Buenos Aires)

Bodyfitness global

1. Delgado Valeria (Salta)

2. Luciani Lorena (Buenos Aires)

3. Marina Danei (Buenos Aires)

4. Echenique Alejandra (Buenos Aires)

5. Bosini Liliana (La Rioja)

Bien-etre jusqu'a 1,63 cm

1. Cisneros Andrea (Buenos Aires)

2. Fondevilla Florencia (Buenos Aires)

3. Rosito Nadia (Buenos Aires)

4. Lobos Anabel (Neuquen)

5. Tazzioli Florencia (Córdoba)

6. Quiñonez Analia (Córdoba)

7. Perez Mirta (Tucuman)

Bien-etre +1,63 Cm

1. Ferrari Natalia (Buenos Aires)

2. Cenbauer Andrea (Santa Fe)

Bien-etre general

1. Cisneros Andrea (Buenos Aires)

2. Ferrari Natalia (Buenos Aires)

Senior jusqu'a 60 kg

1. Fassio Gerardo Tucumán

2. (Caba) Llero Ariel (Santa Fe)

3. Alfaro Carlos (Caba)

Senior jusqu'a 65 kg

1. Lopez Lodi Santiago (Buenos Aires)

2. Guedes Alejandro (Buenos Aires)

Senior jusqu'a 70 kg

1. Mongelos Gastón (Rio Negro)

2. Leonardo Ivan (Buenos Aires)

3. Barrios Gustavo (Buenos Aires)

4. Caon Mario (Córdoba)

5. Saez Nelson (Córdoba)

6. Mardone Gerardo (Neuquen)

Senior jusqu'a 75 kg

1. Rojas Atilio (Entre Ríos)

2. García Luis (Buenos Aires)

3. Aranda Mario (Buenos Aires)

4. Ilheu Brian (Buenos Aires)

5. Roca José (Salta)

6. Bastian Matícomme (Santa Fe)

7. Lopez Traynor Matícomme (Buenos Aires)

8. Gonzalez Pellegrini Rodrigo (Corrientes)

Senior jusqu'a 80 kg

1. Viñcomme Buteler Tomás (Córdoba)

2. Lozupone Mauro (Caba)

3. Constanzo Jorge (Neuquen)

4. Fontaiña Dario (Buenos Aires)

5. Mora Richard (Rio Negro)

6. Murua Guillermo (Córdoba)

7. Galleguillo Ruben (San Juan)

8. Gonzalez Marcelo (Neuquen)

9. Orcuño Eduardo (Buenos Aires)

Senior jusqu'a 85 kg

1. Juarez Luis (Buenos Aires)

2. Aravena Pablo (Neuquen)

3. Leal Matícomme (Córdoba)

4. Montiel Maximiliano Formosa

5. Ledesma Sergio (Buenos Aires)

6. James Darío (Buenos Aires)

7. Gonzalez Hernan (Santa Fe)

8. Fucci Pablo (Buenos Aires)

9. Retamozo Javier (Buenos Aires)

10. Nocera Diego (Buenos Aires)

11. Pelletti Sergio (Santa Fe)

Senior jusqu'a 90 kg

1. Miranda Eduardo (Córdoba)

2. Duran Gabriel (Buenos Aires)

3. Nicolás Square (Salta)

4. Marche Gustavo (Buenos Aires)

5. Rodriguez Lucio (Santiago Del Estero)

6. Puey Maximiliano (Buenos Aires)

7. Gallego Emiliano (Buenos Aires)

8. Funes Cristian (Santa Fe)

9. Moreno Victor (Buenos Aires)

10. Nicolás Square (Salta)

11. Garcíun José (Córdoba)

12. Chiardola Hernán (Entre Ríos)

13. Farias Sergio (La Rioja)

Senior jusqu'a 95 kg

1. Manresa Diego (Buenos Aires)

2. Chumbita Miguel (La Rioja)

3. Arriola Humberto (Buenos Aires)

Senior jusqu'a 100 kg

1. Duran Daniel (Caba)

2. Sain José Luis (Buenos Aires)

3. Pereira Joaquin (San Juan)

4. Alvarez José María (Córdoba)

Senior +100 kg

1. Cortez Rodrigo (Buenos Aires)

2. Chinetti Ignacio (Buenos Aires)

3. Casoli Sebastian (Santa Fe)

General senior

1. Cortez Rodrigo (Buenos Aires)

2. Duran Daniel (Caba)

3. Miranda Eduardo (Córdoba)

4. Juarez Luis (Buenos Aires)

5. Manresa Diego (Buenos Aires)

6. Rojas Atilio (Entre Ríos)

7. Viñcomme Buteler Tomás (Córdoba)

8. Mongelos Gastón (Rio Negro)

9. Lopez Lodi Santiago (Buenos Aires)

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

The seemingly unassailable world of the male creative genius seems to be crumbling: Roman Polanski and Bill Cosby were recently expelled from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Junot Diaz stepped down as Pulitzer Prize chair after multiple women have spoken out about his pattern of harassment; and, 10 years after David Foster Wallace’s death, Mary Karr is reminding the world of his persistent abuse and stalking. In this unique social and political moment, a previously untouchable artistic archetype has finally become something close to vulnerable.

Genius is power. It is unquantifiable, uncontainable, and like beauty, exists in the eyes of the beholder. Genius enhances access—sexual, social, economic, political. It is a collective agreement—or, in many cases, a collective lie—that grants boundless latitude to those we anoint with the title.

But genius is also an indelibly gendered currency used by men—almost always men—of means and success to purchase license. The lie of genius is inextricable from the lie of meritocracy: Culture dictates that these men have risen to fame and success because of their unstoppable genius. But now that so many geniuses stand accused of abuses of power including sexual assault and violence; and as debates about separating the art from the artist spill into every corner of media and pop culture, the aesthetic alibi that artistic genius exists unfettered by lowly considerations like morality may no longer hold up under scrutiny.

With the rise of auteur theory in the mid–20th century, film joined the ranks of other fine arts, like painting and writing, that have long cultivated the mythology of the genius. Auteur theory, originating in French film criticism, credits the director with being the chief creative force behind a production—that is, the director is the “author.” Given that film, with its expansive casts and crews, is one of the most collaborative art forms ever to have existed, the myth of a singular genius seems exceptionally flawed to begin with. But beyond the history of directors like Terrence Malick, Woody Allen, and many more using their marketable auteur status as a “business model of reflexive adoration,” auteur worship both fosters and excuses a culture of toxic masculinity. The auteur’s time-honored method of “provoking” acting out of women through surprise, fear, and trickery—though male actors have never been immune, either— is inherently abusive. Quentin Tarantino, Lars Von Trier, Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick, and David O. Russell, among others, have been accused of different degrees of this, but the resulting suffering of their muses is imagined by a fawning fanbase as “creative differences,” rather than as misogyny and as uncompromising vision rather than violence. Allegations that Tarantino forced Uma Thurman, for instance, to disastrously perform her own driving stunt in Kill Bill: Volume 2—as she put it, part of a dehumanization “to the point of death”—is not dissimilar to Alfred Hitchcock’s torment of the actress Tippi Hedren, both dynamics masquerading as artist-muse relationships transcending common sense. As Imran Siddiquee writes of genius directors and abusive behavior: “Many of the ‘greatest’ artists in our most influential visual artform continue to be celebrated for their own obsessive, often abusive exercises of power and control.”

Daniel Day-Lewis’s temperamental dressmaker Reynolds Woodcock in 2017’s critically lauded Paul Thomas Anderson film Phantom Thread has all the makings of a genius: He is successful; he is considered a visionary by the elite; he is messy; he is twisted; and he preys on young women. Phantom Thread was a frontrunner in the Oscars race this year, along with Darkest Hour, a character study of of Winston Churchill at the dawn of Britain’s entry into World War II. Gary Oldman (alleged wife beater), won Best Actor for his role as Churchill; elsewhere at the Oscars, Kobe Bryant (charged with sexual assault in 2003) won for best animated short. Guillermo Del Toro took home the Best Director Oscar for The Shape of Water, which also won Best Picture—and while the film’s win is notable given that no film with a female protagonist has won the award in 14 years, Del Toro’s explicit supportof Roman Polanski (accused of sexual assault by five people; charged with drugging and raping a minor and then fleeing the United States to avoid sentencing) make his position as a supposedly progressive director a tenuous one at best. The Academy Awards have always been deeply entrenched in establishment capitalism and Hollywood liberal lip service, but amid the flurry of the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements, the 2018 awards offered an instructive example of what still holds primacy in the film industry: the sometimes difficult and troubled, often abusive, and always male genius.

Men like Polanski retain artistic cred and social license because gatekeepers and fans argue that their cultural contributions outweigh their individual transgressions and crimes. It is not that passive consumers of art don’t recognize that their idols may be flawed: It’s that genius is imagined as a separate faculty that exists beyond ethics and morality. Genius is unemotional and objective, elevated beyond such paltry concerns. Of course the generous leaps of imagination and apologism offered to men of genius do not apply to women and gender-nonconforming creators, so if the latter should distinguish themselves, it is not because they are genius, but it is because they are “different.”

Superlative women have always been encouraged to believe they are notable because of an inherent “difference” from other girls; this difference is what distinguishes them in creative fields dominated by white men. I once thought I had the “androgynous mind” Virginia Woolf says is necessary to creativity. Mary Wollstonecraft, in her groundbreaking 1792 treatise A Vindication Of The Rights Of Woman, wondered whether the “few extraordinary women” in history were indeed “male spirits, confined by mistake to female frames.” Even Ursula K. Le Guin, whose revolutionary fiction challenged contemporary humanity’s preoccupation with gender, said some strange stuff about her own conception of herself as a “generic he,” a “poor imitation,” and a “substitute man.”

While we know it is both reductive and essentialist to reason this way, it’s historically understandable. The cultural misogyny that underlies the archetype of the male genius has ancient roots. According to Christine Battersby’s 1989 book Gender and Genius: Towards a Feminist Aesthetics, the 19th-century reworked an “older rhetoric of sexual exclusion” from Renaissance ideas about sexual difference in the arts (which were themselves based on the ancient Greeks and Romans). But the Romantics contributed something unique to “anti-female traditions”: While emotionality and expression—traditionally “feminine” attributes—rose in prominence, women themselves were further downgraded as artistic inferiors. Notes Battersby: “The Romantic artist feels strongly and lives intensely: the authentic work of art captures the special character of his experience.” And his art became his individualistic expression.

Originality and creativity wasn’t always inherent to artistic practice. Greeks thought of art as mimetic; the poet as a prophet; painting and sculpture pretty facsimiles of the natural world. The Middle Ages similarly viewed the artist as ungod-like, simply an imitator rather than a creator. The term “masterpiece,” had less to do with terrific originality and more to do with the “piece of work produced by an apprentice who showed sufficient skill.” A master was a “trade-union leader”—and women were active in these guilds as well. “Hostility towards women in the arts only increased when the status of the artist began to be distinguished from that of the craftsman…suitable only for the most perfect (male) specimens of humanity,” writes Battersby. She dates this change to when artists began gaining patronage during the Renaissance, freeing artistic creation from religious restrictions. In other words, when a great deal of money entered into the equation, art became profitable and it suited men to push out competition.

The modern term “genius” comes from the melding of two words: “genius,” a symbol of fertility represented by a little boy, and “ingenuity,” or skill. While Renaissance women lacked genius, they were artistic inferiors because they lacked “ingenium”—according to Juan Huarte’s 1575 Examen de Ingenius, men, in the Aristotelian fashion, were hot and dry; women, cold and wet, were a “lesser man.” (Aristotle also thought women were “flower pots” and sterile—creativity and procreativity both being male attributes.) Huarte’s physiological reasoning, though widely discredited, was later referenced by Schopenhauer, whose argument that women “lack all higher mental faculties” is a good example of Romantic reworking of cultural misogyny. (It might be worth noting that Schopenhauer is a well-known touchstone of Woody Allen’s many autobiographically based neurotic male protagonists.)

Further, madness and deviance were idiosyncrasies worked into the masculine artistic template. Artists, once expected to uphold societal values, became “countercultural” around the time of Lord Byron, who was once described by an ex-lover as “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.” The image of the antihero, the messy, the eccentric, the intoxicated artist persisted from the Romantic period through today. And while craziness was celebrated in the elite men, “female madness” was stigmatized. As Vox writer Tara Isabella Burton notes, the male artistic establishment begets the tortured, unruly genius sex: “That female flesh is the reward for a male job well done is not an uncommon cultural phenomenon in any field, but in the arts, that dynamic often takes on a faux-spiritual aspect.”

Even as the #MeToo movement picks up momentum, famous men who have sustained public critique in the past few months are already plotting their comebacks, with ample assistance from industry media. Tarantino, a man accused of choking Thurman and Diane Kruger for the sake of on-camera authenticity; who told Rose McGowan he used to jerk off to her; and who publicly defended Polanski, has unveiled his latest enterprise: a movie about Charles Manson. Charlie Rose has reportedly floated a comeback via a talk show in which he would interview men like Louis C.K. brought down by#MeToo—thereby facilitating their own comebacks—and Matt Lauer apparently hopes to be back on television screens as well. Despite the recent spate of high-profile falls from grace, the culture of media and art world are arranged such that neither whisper nor lawsuit will be able to fell geniuses for long.

Those who try to separate the art from the artist are setting up an illogical argument: The art was alwaysseparated, which is why these male auteurs had the the license, the support, and the cover to victimize as they did and still make more celebrated art. In the aftershocks of predatory unveilings, we have seen multitudes mourn the loss of the genius of these men. We need to now consider that we have elevated what we’ve inscribed as genius at the expense of the humanity and potential of people they silenced, erased, and preyed upon. We need to examine the destruction wrought by the archetype, and acknowledge that we have let it fuel rape culture and sexual exploitation. We need to acknowledge that genius has been a construct all along—that it may not actually exist.

1K notes

·

View notes