#National Day of Action for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls

Text

Today (October 4) is Canada's National Day of Action for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG).

Indigenous women and girls are at a disproportionate risk for violence. Indigenous women are women are over-represented among Canada’s murdered and missing women. (They are also disproportionately incarcerated and involved in the sex trade.) This is a significant, persistent, and deliberate pattern of systemic racial and sex-based human rights violations.

Because Canada is Canada, the government decided to do an inquiry report to look into this crisis that we already knew was a crisis. This report called Canada's MMIWG crisis "genocide." This is neither exaggeration nor understatement.

Despite this report, and the concrete actions it listed that the government could take to address the MMIWG crisis, the Canadian government has taken only symbolic action to protect Indigenous women and girls nation-wide.

Because today is the day of action, here are some actions you can take.

First, educate yourself. Read the Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.

Among the calls for justice in the report are eight actions all Canadians should take:

"1. Denounce and speak out against violence against Indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA people.

2. Decolonize by learning the true history of Canada and Indigenous history in your local area. Learn about and celebrate Indigenous Peoples’ history, cultures, pride, and diver- sity, acknowledging the land you live on and its importance to local Indigenous communities, both historically and today.

3. Develop knowledge and read the Final Report. Listen to the truths shared, and acknowl- edge the burden of these human and Indigenous rights violations, and how they impact Indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA people today.

4. Using what you have learned and some of the resources suggested, become a strong ally. Being a strong ally involves more than just tolerance; it means actively working to break down barriers and to support others in every relationship and encounter in which you participate.

5. Confront and speak out against racism, sexism, ignorance, homophobia, and transpho- bia, and teach or encourage others to do the same, wherever it occurs: in your home, in your workplace, or in social settings.

6. Protect, support, and promote the safety of women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA people by acknowledging and respecting the value of every person and every community, as well as the right of Indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA people to generate their own, self-determined solutions.

7. Create time and space for relationships based on respect as human beings, supporting and embracing differences with kindness, love, and respect. Learn about Indigenous principles of relationship specific to those Nations or communities in your local area and work, and put them into practice in all of your relationships with Indigenous Peoples.

8. Help hold all governments accountable to act on the Calls for Justice, and to implement them according to the important principles we set out."

If you are Canadian, please write to your elected officials and demand that they act on the report's Calls for Justice. (Amnesty International provides some templates for letter writing: 1, 2, 3, 4)

If you are not Canadian, I would encourage you to write to your government and call on them to take formal action against Canada to make our government take action to protect Indigenous women and girls.

Please stop letting us get away with being 'the good guys' just because we're next to the States. The countless deaths and disappearances of Indigenous women and girls have not been enough to force Canadians to act. We need international backlash.

I encourage you to educate your friends and family on this issue. Too many Indigenous women and girls go without justice everyday.

(And because I know Tumblr is full of Americans and this isn't just a Canada problem, I'm linking this report on MMIWG in the US.)

#mmiwg#missing and murdered indigenous women#National Day of Action for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls#I cannot stress enough that my country is actively doing genocide#tw violence against women

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women: An Ongoing Tragedy

Shaina Tranquilino

October 4, 2023

The issue of missing and murdered Indigenous women is a devastating tragedy that has plagued Indigenous communities for decades. Despite being deeply rooted in the history of colonization, it remains an ongoing crisis that demands immediate attention. This blog post aims to shed light on this heartbreaking reality and urges society to acknowledge, address, and support initiatives aimed at ending the violence.

A Historical Context:

To truly understand the gravity of the situation, we must recognize the historical context in which this epidemic has unfolded. Since European colonization began in North America, Indigenous women have faced systemic discrimination, marginalization, and violence. These injustices persist today as a direct result of centuries-long oppression and the erosion of Indigenous cultures.

Disturbing Statistics:

The statistics surrounding missing and murdered Indigenous women are both shocking and disheartening. According to a 2016 report by the National Crime Information Center (NCIC), there were over 5,700 cases of missing or murdered Indigenous American women recorded in the United States alone. Alarmingly, many believe these numbers may be underestimated due to underreporting or misclassification by law enforcement agencies.

Root Causes:

Numerous factors contribute to this crisis. Poverty, limited access to education and healthcare services, high rates of domestic violence within communities, institutional racism, inadequate law enforcement response, and human trafficking all play significant roles in perpetuating this cycle of violence against Indigenous women.

The Need for Awareness & Advocacy:

Raising awareness about this issue is crucial towards mobilizing action to end it. It requires educating ourselves and others about the plight faced by Indigenous women who continue to disappear or be victimized every day. Social media campaigns like #MMIWG (Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls) have played a pivotal role in bringing attention to their stories while demanding justice.

Government Action & Accountability:

Addressing this crisis necessitates a multi-faceted approach. Governments at all levels must take concrete steps to address the root causes of violence against Indigenous women, including improving collaboration between law enforcement agencies, enhancing victim services, and implementing culturally sensitive policies. Additionally, funding programs that empower Indigenous communities and strengthen support systems are essential for long-term change.

Community Empowerment:

Indigenous communities have been fighting tirelessly to protect their women and girls. Supporting grassroots organizations led by Indigenous people who understand the unique challenges faced by their community is crucial in eradicating this issue. By amplifying voices from within these communities, we can ensure that culturally appropriate solutions are implemented while fostering healing and resilience.

The missing and murdered Indigenous women crisis demands urgent attention from society as a whole. Recognizing the historical context, understanding the systemic issues involved, advocating for awareness, holding governments accountable, and empowering affected communities are all integral components of bringing an end to this deeply entrenched tragedy.

To honour the lives lost and prevent future victimization, it is our collective responsibility to stand in solidarity with Indigenous communities and work towards creating a world where every woman feels safe, valued, and protected. Only through unity can we hope to achieve justice for the missing and murdered Indigenous women who deserve nothing less than our unwavering commitment to ending this heartbreaking reality once and for all.

#MMIW#MMIWG#Indigenous women#missing and murdered indigenous women#justice for our sisters#protect our women#no more stolen sisters#support Indigenous communities#stop the violence#raise awareness#honouring our ancestors#remember their names#break the silence#stand with Indigenous women

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today is May 5th, the national day of remembrance for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, children, Trans, and Two-Spirited people. Here are some statistics and facts that more people should be aware of along with resources as I go.

• On average, the 1st sexual assault on an Indigenous child happens at 13 years old.

• More than 4 out of 5 American Indian and Alaskan Native Women have experienced violence in their lifetime.

•Indigenous People are murdered at a rate 10x the National Average.

• Most violent crimes perpetrated on Native People are committed by non Native People.

• The 2nd Leading cause of death for American Indian and Alaskan Native girls aged 1-4 is homicide.

• Recently A Statistics Canada analysis found 81 per cent of Indigenous women who had been in the child-welfare system had been physically or sexually assaulted in their life.

• Homicide is the 3rd leading cause of death among Native Girls and Women aged 10-24 and jumps to 5th from 25-34

• There were 506 cases of MMIWG in 71 urban cities across the U.S., In New Mexico alone, there is the highest incidents of MMIW sitting at 78 cases. Keep in mind that cases involving LGBTQ2S+ have been undercounted.

Here is an update of the bodies of Indigenous children found on Residential School properties.

As of March 2022, 10,028 unmarked graves have been found at former residential schools across Canada.

Under the Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, The US is reported to begin searching residential schools, through the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiativebut it’s not currently clear when this will start.

There is so much overwhelming information, but there does seem to be some hope, 16 states including Colorado, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Wyoming, and Kansas have taken legislative action to address MMIWR, and hopefully along with the search of residential schools, we can start bringing all of our relatives home.

649 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Just some incomplete notes as a friendly reminder that

May 5th is National Day of Awareness for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, February 14th is the date for MMIW Marches across Canada, and October 4th is the day of Vigil for our stolen sisters

MMIW also includes girls as young as infants, and gender diverse individuals → MMIWG2S+

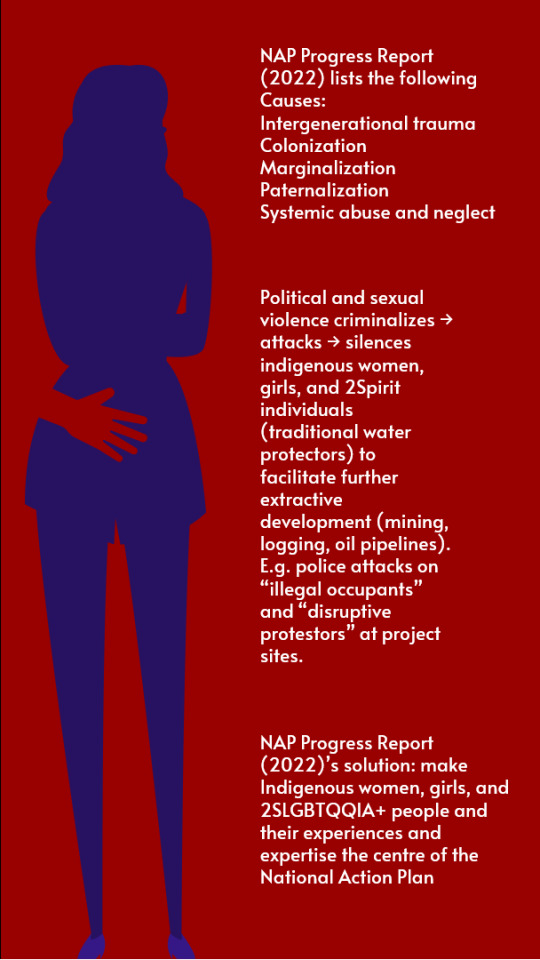

While government organizations appear to be raising awareness, creating National Action Plans and declaring National Emergencies, police are complicit in kidnapping and murdering our people wether through acts of violence (for personal gratification or to enable further extractive development which increases raises risk factors) or refusal to investigate (due to jurisdictional issues, to cover it up, or because they’re conditioned to believe that our deaths aren’t worth explaining and that our lives don’t matter).

Colonial violence is alive and well, and it’s up to each and every one of us to contribute to meaningful changes to protect our women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA+ people.

There are tons of resources for learning more, but I highly recommend checking out Sovereign Bodies Institute at https://www.sovereign-bodies.org/

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

National Day of Awareness for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls and Two-Spirit People

May 5th was the day,

A blog post at Sicangu Community Development Corporation explains the purpose:

Maybe you’ve seen the hashtag #MMIW on social media, or its counterpart, #MMIWG2. Both stand for Missing and Murdered Indigenous women, the latter adding on G2 for Girls and Two-Spirits. The hashtag was created to spread awareness for a generations-long silent epidemic that has stolen the lives of Indigenous Women, Girls and Two-Spirits across Turtle Island (North America).

The National Indigenous Women's Resource Center has more important information. I was very moved by Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada has unveiling The Red Amautiit Project.

I suspect for a lot of White people, I'm "too woke." But most of the time I'm rather chagrined by how unaware I am, and in particular how I turn away from difficult realities. On May 5th, I couldn't think of any useful way to raise awareness of the issue of missing and murdered indigenous women.

Today, E. Jean Carroll won a judgment against Donald Trump. Carroll throughout the whole process has stated the the me too movement inspired her to come forward. That’s made me think again about “awareness.”

Back when the hashtag #MeToo was being posted everywhere, I noticed a male friend had posted #MeToo. I thought at the time something like: It's not for you. There are many particulars about sexual violence that are very important. But in in a general sense facing the reality of sexual violence is the critical thing for everybody. And by facing it to become open to healing action.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The trans cult just have to give themselves another day. And to have this just two days after May 5th which is National Day of Awareness for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls is just extra disgusting.

ASBURY PARK, N.J. -- Asbury Park has declared May 7 "Drag Queen Visibility Day."

The proclamation comes after several pieces of anti-drag and anti-trans legislation were proposed across the country.

A day-long festival will be held on May 7 highlighting drag performers.

The proclamation will also be recognized by the governor's office.

May 5 is commemorated as National Day of Awareness for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. The day became recognized in 2017 when Montana Senators Steve Daines and Jon Tester responded to the murder of Hanna Harris on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation, as well as the cumulation of other murders and abductions of Native women and girls. Since then, grassroots efforts at local, regional, national, and international levels have grown as Indigenous families, advocates, and Indigenous nations continue to call attention to the violence and galvanize action in response to the MMIWG crisis.

We encourage you to join community actions this week to raise awareness and call on governments to be accountable to the injustices and systemic barriers embedded in federal and local legislation that perpetuate this crisis. As Hanna Harris’s mother, Malinda Limberhand, aptly said: “As a mother, nothing will replace the loss of my daughter, but by organizing to support the National Day of Awareness and creating the changes needed, I know it will help others. And Hanna and so many others will not be forgotten.”

7 Actions to Take for National Day of Awareness for #MMIWG

1. Wear red, take a photo, and share it on social media to bring awareness of #MMIWG.

Share a photo. Make sure to use hashtags #MMIW, #MMIWG, #MMIWG2S, #MMIWActionNow, and #NoMoreStolenSisters!

2. Join the National Indigenous Women's Resource Center in these 3 calls to action:

Urge your Senators to pass Family Violence Prevention & Services (#FVPSA) reauthorization with key Tribal provisions: n8ve.net/Ts6M5

Tag The Justice Department, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, and the US Interior on social media and demand they immediately implement the Not Invisible Act

Tag the Justice Department and the FBI on social media and demand they improve MMIW data collection under Savanna’s Act . #MMIW, #MMIWG, #MMIWG2S, #MMIWActionNow #NoMoreStolenSisters

3. Watch "Voices Unheard."

A short film by Native Hope. Marty Coulee is a Native American entrepreneur living the good life. When her Native American business partner Jess, vanishes without a trace on a business trip to Arizona, Marty becomes a voice for the voices unheard.

4. Watch “Bring Her Home.”

This film follows three Indigenous women – an artist, an activist, and a politician – as they fight to vindicate and honor their missing and murdered relatives who have fallen victims to a growing epidemic across Indian country. Despite the lasting effects from historical trauma, each woman must search for healing while navigating racist systems that brought about this very crisis.

5. Listen to our Indigenous Rights Radio interview with Leya Hale.

Leya Hale (Sisseton Wahpeton Dakota and Navajo) is a storyteller, documentary filmmaker, and a producer with Twin Cities PBS (TPT). Her recent film, "Bring Her Home," addresses the epidemic of Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women in the United States.

6. Include Two-Spirit Relatives in Awareness of MMIWG2S.

It is imperative to include Two-Spirit relatives in the raising of awareness of MMIWG. Read about the meaning of Two-Spirit to learn about the many intersections of violence that threaten Two-Spirit people. To learn more and give support, visit organizations such as Families of Sisters in Spirit and read this organizing toolkit from the Sovereign Bodies Institute. For immediate help with a case of domestic violence or dating violence, please visit StrongHearts Native Helpline's online Chat Advocacy or helpline (1-844-7NATIVE).

7. Claim free print subscription for NIWRC’s Restoration of Native Sovereignty and Safety for Native Women magazine, courtesy of Urban Indian Health Institute.

#Asbury park#New Jersey#may 7#drag Queen Visibility Day#Drag queens don’t need more visibility#how many days does the trans cult have now?#And how many of this days conflict or are very close to days dedicated to other groups?

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hiii! Can we maybe have some positivity for Indigenous systems? This week's the Week of Action to Awareness and yesterday was the National Day of Awareness for MMIGW2S ( Missing and Murdered Girls, Women and Two Spirits ) and I& know it's very hard on us& personally. An elder told me& it's a community & intergenerational trauma that effects everyone, regardless of other intersecting identities, even those who aren't personally affected by it, and as a multigenic DID Native system, it really hits close to home and i'm& sure the same can be applied to other Indigenous systems. We& had to call a helpline several times yesterday, so it would be greatly appreciated because we need that support and there's a lot of undiagnosed Indigenous systems out there because we're so heavily underdiagnosed because of our indigeneity.

Hi - absolutely! We would be quite happy to write this post. We’ve bumped this ask up so we can have the positivity post on our blog before the Week of Action is over. You& can expect it on our blog tomorrow night at 8PM EST!

We understand that life can be incredibly challenging for indigenous people, and indigenous systems especially! Indigenous systems will always be welcome and uplifted in our spaces. Thank you& so much for requesting this - we hope our post will be cheerful and respectful!

(Also we got two quite similar asks from you&! We’re posting this one and will probably delete the other since they’re both very similar and are requesting similar positivity posts. We hope that’s okay!)

🌸 Margo and 💚 Ralsei

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s American Thanksgiving time again, for those who celebrate it. It’s also Native American Heritage Month, with Thursday being National Day of Mourning and Friday being Native American Heritage Day. This year, specifically, is the 53rd annual Day of Mourning.

“The National Day of Mourning protest was founded by Wamsutta Frank James, an Aquinnah Wampanoag tribal member.” This started in 1970, in protest at a speech at a Thanksgiving event for Massachusetts, where Wamsutta was supposed to talk about the Thanksgiving myth, but instead wrote a speech about the fate of the Wampanoag at the hands of the Pilgrims, as well as ongoing colonization. You can read an excerpt here.

Speeches at the annual gathering on Cole’s Hill include current topics relevant to Native Americans, such as the Supreme Court cases surrounding the Indian Child Welfare Act and Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls and Two-Spirit People.

I usually like to end posts like this with a “call to action.” But honestly, I’m not the right person for that. You can start with this list of 100 things you can do to be an ally to Indigenous communities. I recommend checking out organizations like Native Women Wilderness, Indigenous Women Hike, or your local tribe, Urban Indian Center, or other Indigenous organization to learn more and see how you can best support Indigenous movements. There are places to make donations to, posts to share, and things to learn.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

instagram

safehalton May 5 is the National Day of Awareness for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls and 2SLGBTQQIA+ peoples. This day, also known as Red Dress Day is recognized as part of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls Week of Action.

On this day, and during this week, we honour and remember all missing and murdered Indigenous Women, Girls and 2SLGBTQQIA people.

The dresses are empty, to symbolize the missing and murdered persons who should be wearing them.

Indigenous women are 12 times more likely to be murdered or missing than any other women in Canada.

#genderbasedviolence

#VAW

#endvaw

#mmiwg2s

#Mmiw

#nomorestolensisters

#SAAM

#women

#endsexualviolence

#survivors

#reddressday

#mentalhealth

#rapeculture

#safehalton

#supportsurvivors

#trauma

#ptsd

#sexualassault

#womenempowerment

#consent

#narcissisticabuse

#sexualabuse

#psychologicalabuse

#sexualassaultawarenessmonth

#sexualabuse

#childhoodabuse

#metoo

#domesticviolence

#domesticviolencesurvivor

#sexualassault

#rapesurvivor

#livedexperience

#Instagram#genderbasedviolence#VAW#endvaw#mmiwg2s#Mmiw#nomorestolensisters#SAAM#women#endsexualviolence#survivors#reddressday#mentalhealth#rapeculture#safehalton#supportsurvivors#trauma#ptsd#sexualassault#womenempowerment#consent#narcissisticabuse#sexualabuse#psychologicalabuse#sexualassaultawarenessmonth#childhoodabuse#metoo#domesticviolence#domesticviolencesurvivor#rapesurvivor

1 note

·

View note

Text

École Polytechnique: Global Fight Against Gender-based Violence

Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau, today issued the following statement on the National Day of Remembrance and Action on Violence Against Women:

“On this National Day of Remembrance and Action on Violence against Women, we remember the 14 young women who were senselessly murdered and the 13 others who were injured at the École Polytechnique de Montréal. Today, we pay tribute to their lives that were tragically cut short simply because they were women, and we reaffirm our commitment to eliminate gender-based violence.

“As we remember the victims of this hateful, cowardly act, we are also reminded that, for many women, girls, and gender-diverse people in Canada and around the world, the violent misogyny that led to this tragedy still exists. The risk of violence is even higher for Indigenous women and girls, racialized women, women living in rural and remote areas, people in 2SLGBTQI+ communities, and women with disabilities. That is why we have and continue to strengthen our laws and ensure supports for victims and survivors of gender-based violence.

“Through the Gender-Based Violence Strategy, we are delivering crucial community-based and trauma-informed support for victims, survivors, and their families. Last year, we launched the It’s Not Just campaign to help young people recognize, build awareness of, and end gender-based violence.

“We are also working with provinces and territories across Canada to implement the National Action Plan to End Gender-Based Violence – which sets a framework to have a Canada free of gender-based violence, with supports for victims, survivors, and their families. We have already announced bilateral agreements with Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Prince Edward Island, Nunavut, the Yukon, Alberta, the Northwest Territories, Ontario, Quebec, and New Brunswick – ensuring supports are readily available and accessible across the country. There is also more work to do to put an end to the ongoing tragedy of missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBTQI+ people. We will continue to work in partnership with Indigenous families, Survivors, leaders, and partners, as well as with provinces and territories, to implement the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls and 2SLGBTQQIA+ People National Action Plan and the Federal Pathway to make our communities safer.

“We are also taking transformative action to strengthen gun control measures and address the alarming role of firearms in domestic and gender-based violence. We banned over 1,500 models of assault-style firearms and their variants, including the weapon used at the École Polytechnique. We implemented a national handgun freeze, restricting the sale, purchase, and transfer of handguns, and through Bill C-21, we can implement some of the strongest measures in Canadian history to tackle gun violence and keep our communities safe.

“As we mark the 16 Days of Activism against Gender-based Violence, I encourage Canadians to honour the victims and survivors of the École Polytechnique massacre. You can wear a white ribbon, attend a vigil in your community, or observe a moment of silence at 11:00 a.m. Together, we can and must put an end to gender-based violence and build a safer, more inclusive future, where everyone can reach their full potential.”

Sources: THX News & The Canadian Government.

Read the full article

#16DaysofActivism#ÉcolePolytechniquemassacre#Gender-BasedViolence#Gender-BasedViolenceStrategy#Guncontrolmeasures#It'sNotJustcampaign#MissingandMurderedIndigenousWomen#NationalActionPlan#NationalDayofRemembrance#Whiteribbon

0 notes

Text

It’s Native American Heritage Month

Photo by Tailyr Irvine

(11/24/2023) In addition to learning and celebrating the history of indigenous peoples, we must support indigenous peoples and communities that are alive today and have been alive for centuries.

I currently live on the lands of the Wyandot, Mississauga, Potawatomi, and Anishinabek people. These people lived here for thousands of years before white settlers colonized the land in the 1800s. I will always support indigenous liberation and sovereignty.

To my non-native US and Canadian followers -- if you’re new to the Land Back Movement, you can start by learning whose land you’re on here. Land acknowledgment is the first step, and from there you can reach out to your neighboring First Nation to start building relationships and learn how you can support them. There are still SO many non-native folks in the U.S. who don’t know the history of American colonialism and acts of state-sanctioned genocide committed against Native Americans -- acts that are still ongoing to this day. I know this is kinda poli sci 101 and this has been said already, but we need to continue educating ourselves and each other. Education is one of our greatest tools in the fight against colonialism and imperialism. Knowing that, I'm sharing some current issues that are threatening indigenous people and communities. These are not exclusively indigenous issues either -- they are issues that concern humanity as a whole.

It is also important we build our communities around things that are positive such as art, literature, and culture. So to bolster these things, I'm also sharing some indigenous content creators, authors, and shops. Thank you to @help-ivebeen-turned-into-aparrot for the recommendations and expanding this list!

Remember history, celebrate Native American heritage, and stay informed! Links below the cut.

Current Major Issues (as of November 2023)

Navajo Nation Water Rights

Overview (NARF)

Resources and how to help (from 2020, still valuable)

Alaskan Ambler Road

Overview (Winter Wildlands Alliance)

Paving Tundra, a short documentary

Take action

Nevada Lithium Mine

Overview (First Nations)

People of Red Mountain/how to help

Missing And Murdered Indigenous Women

Info and overview (Native Hope)

Mission

Native American History and Culture

The books and articles with links are freely available. To read the others, you might be able to find them at a nearby library using WorldCat.

Introduction to Native American History by Native Hope

Stories, Dreams, and Ceremonies: Anishinaabe ways of learning by Leanne Simpson

Origin and Traditional History of the Wyandotts by Peter D. Clarke

Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 11: Great Basin by William C. Sturtevant and Warren L. D'Azevedo

Shoshonean Peoples and the Overland Trails by Dale L. Morgan

Diné History of Navajoland by Klara Kelley and Harris Francis

Native American-Owned Shops

Thunder Voice Hat Co. - handmade hats, hat accessories, and other apparel.

Kotah Bear - blankets, robes, and jewelry. Owned by two people of Navajo Nation, selling art and jewelry made by Navajo and Pueblo artists.

Manitobah - moccasins, mukluks, and other winterwear. A global brand founded by Sean McCormick, a Métis entrepreneur. Also has the Indigenous Market, which sells handmade products by indigenous artists from Canada and the US.

Little Inuk Beadwork - jewelry and accessories. Made by Lillian Putulik, Inuk artist.

Mobilize - streetwear and fashion. Founded by Dusty LeGrande, Nehiyaw artist and activist. Based in Edmonton, CA.

Authors

Moniquill Blackgoose - science fiction and fantasy. Seaconke Wampanoag author. To Shape A Dragon's Breath

Angeline Boulley - young adult thriller fiction. Chippewa author. Firekeeper's Daughter

Cherie Dimaline - Métis author, mostly YA fiction. The Marrow Thieves, Hunting by Stars, Funeral Songs for Dying Girls

Darcie Little Badger - science fiction and fantasy. Lipan Apache author. Elatsoe, A Snake Falls to Earth

Stephen Graham Jones - horror fiction. Blackfoot Native American author. The Only Good Indians, Mongrels, After the People Lights Have Gone Off

Delphine Red Shirt - autobiographies, culture, oral tradition. Oglala Lakota author. Turtle Lung Woman's Granddaughter, Bead on an Anthill: A Lakota Childhood, George Sword's Warrior Narratives

Dani Trujillo - romance. Chicana/Pueblo author. Lizards Hold the Sun

Content Creators

Che Jim - humor, skits, social and political issues. Diné/Nishnaabe/Chicano content creator.

Lillian Putulik - art and jewelry. Nunavik Inuk artist.

Bossii Masu Nagaruk - current events and social and political issues. Iñupiaq content creator.

David Little Elk - educating about and celebrating Oglala Lakota tribal wisdom. Oglala content creator.

Edgar Martin del Campo - educating about cultures, languages, and religions of indigenous peoples of North and South America.

Casey (aka Hot Glue Burns on insta) - cosplay and cosplay design/creation.

#native american heritage month#important#I follow all these content creators and some were recommended by my friend L#by no means a comprehensive list and I encourage everyone to go follow more indigenous folks if you aren’t already#tried to include very broad history as well as more specific history#I focused on groups from the great basin and around the great lakes only because that happens to be my wheelhouse#thank you again L I love you!

0 notes

Text

Holidays 10.4

Holidays

Blessing of the Animals at the Cathedral Day

Cable Street Day (UK)

Carrying in the Pudding (London, UK)

Ctenophore Day

Day of Peace and Reconciliation (Mozambique)

Day of the Space Forces (Russia)

Dick Tracy Day

eDay (New Zealand)

Forever Alone Day

Get Your Friend Day

Global Work From Home (WFH) Day

Golf Lovers Day (a.k.a. National Golf Day)

Hug a Non-Meat Eater Day

Improve Your Office Day

International Dakota Johnson Day

International No Disposable Cup Day

International Sputnik Day

International Toot Your Flute Day

International Walk & Bike to School Day

International Wound Hygiene Day

International Zookeeper Day

Kids Music Day

Kindness to Animals Day

National CB Radio Day

National Clothespin Day

National COVID-19 Remembrance Day

National Day of Action for Missing & Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls & Two-Spirit People (Canada)

National Day of Chilean Music (Chile)

National Day of Life (Colombia)

National 4-H Spirit Day

National Laura Day

National Ship in a Bottle Day

National Side Bae Day

National Sisters in Spirit Day (Canada)

National Talk Like a Trucker Day

National Teach German Day

National Trucker’s Appreciation Day

Peace and Reconciliation Day (Mozambique)

See the Light Day

Snoopy Day

Territory Day (Christmas Island)

Thanksgiving Day (Saint Lucia)

Thimpu Tsechu (Bhutan)

Ten-Four Day

What’s the Frequency, Kenneth? Day

Winter Squash Day (French Republic)

World Animal Day

World Day of Bullying Prevention

World Dyslexia Day

World Pet’s Day

World RBD Day

Food & Drink Celebrations

Canadian Beer Day

Cinnamon Roll Day (Finland)

Kanelbullens Dag (Cinnamon Bun Day; Sweden)

National Frappe Day

National Taco Day

National Vodka Day

Sardines Day (Japan)

1st Wednesday in October

Balloons Around the World Day [1st Wednesday]

California Clean Air Day (California) [1st Wednesday]

Canadian Beer Day (Canada) [Wednesday before 2nd Monday]

Children’s Day (Chile) [1st Wednesday]

Energy Efficiency Day [1st Wednesday]

International Walk to School Day [1st Wednesday]

National Coffee with a Cop Day [1st Wednesday]

National Kale Day [1st Wednesday]

National Pumpkin Seed Day [1st Wednesday]

Nottingham Goose Fair begins (UK) [1st Wednesday thru Sunday]

Random Acts of Poetry Day [1st Wednesday]

Semana Morazánica begins (Honduras) [1st Wednesday]

Walk Maryland Day (Maryland) [1st Wednesday]

World Financial Planning Day [1st Wednesday]

Independence Days

Belgium (from the Netherlands, 1830)

Lesotho (from UK, 1966)

Feast Days

Amun (a.k.a. Ammon; Christian; Saint)

Aurea (Christian; Saint)

Beethoven (Positivist; Saint)

Buster Keaton Day (Church of the SubGenius; Saint)

Chong Yeung Festival (Festival of Ancestors; Macau)

David & Dickory (Muppetism)

Double Ninth Festival (China) [9th day of 9th Lunar month]

Edwin, King of Northumberland (Christian; Saint)

Elder’s Day (China) [9th Day of 9th Lunar Month]

Feast of Hathor (Egyptian God of Drunkenness)

Fortified Wines Day (Pastafarian)

Francesco Solimena (Artology)

Francis of Assisi (Christian; Saint)

Frederic Remington (Artology)

Ieiunium Cereris (Fast of Ceres; Ancient Rome)

Jean-François Millet (Artology)

Jejunium Cereris (Feast for Demeter; Pagan)

Lucas Cranach the Younger (Artology)

Marcus and Marcian (Christian; Martyrs)

Martyrs of Triers (Christian; Saint)

Petronius of Bologna (Christian; Saint)

Lucky & Unlucky Days

Prime Number Day: 277 [59 of 72]

Sakimake (先負 Japan) [Bad luck in the morning, good luck in the afternoon.]

Unfortunate Day (Pagan) [46 of 57]

Unlucky Day (Grafton’s Manual of 1565) [46 of 60]

Premieres

ABC After School Specials (TV Series; 1972)

All the Right Reasons, by Nickelback (Album; 2005)

An American in Paris (Film; 1951)

The Batman Superman Movie: World’s Finest (WB Animated Film; 1997)

Beverly Hills 90120 (TV Series; 1990)

Bound (Film; 1996)

Bridge of Spies (Film; 2015)

Commando (Film; 1985)

Dolemite Is My Name (Film; 2019)

The EGGcited Rooster (WB MM Cartoon; 1952)

Encyclopedia Brown, Boy Detective, by Donald J. Sobol (Novel; 1963)

Extraordinary Machine, by Fiona Apple (Album; 2005)

Gravity (Film; 2013)

Is You Is Or Is You Ain’t My Baby, by Louis Jordan (Song; 1943)

Joker (Film; 2019)

Knight Templar, by Leslie Charteris (Novel; 1930) [Saint #4]

The Last Emperor (Film; 1987)

Leave It To Beaver (TV Series; 1957)

The Longest Day (Film; 1962)

Lost Horizon, by James Hilton (Novel; 1933)

The Man in the High Castle, by Philip K. Dick (Novel; 1962)

The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays, by Albert Camus (Essays; 1942)

Neon Genesis Evangelion (Japanese Anime; 1995)

Notes on Democracy, by H.L. Mencken (Political Book; 19

The Thing You Do (Film; 1996)26)

The Saint, starring Roger Moore (TV Series; 1962)

Trick or Treat Scooby-Doo! (WB Animated Film; 2022)

200 Motels, by Frank Zappa & The Mothers of Invention (Soundtrack Album; 1968)

Walls & Bridges, by John Lennon (Album; 1974)

Today’s Name Days

Aurea, Edwin, Franz (Austria)

Franciska, Franjo, Franka (Croatia)

František (Czech Republic)

Franciscus (Denmark)

Randel, Rando, Randolf, Ranno (Estonia)

Frans, Saija, Saila (Finland)

Aure, Bérénice, François, Frank, Orianne, Sarah (France)

Aurora, Edwin, Emma, Franz, Thea (Germany)

Ierotheos, Kallisthenis, Verina (Greece)

Ferenc (Hungary)

Francesco, Petronio (Italy)

Francis, Modra, Zaigonis (Latvia)

Eivydė, Mąstautas, Pranas, Pranciškus (Lithuania)

Frank, Frans (Norway)

Edwin, Franciszek, Konrad, Konrada, Manfred, Manfreda, Rozalia (Poland)

Ierotei (Romania)

František (Slovakia)

Francisco (Spain)

Frank, Frans (Sweden)

Damara, Damaris, Berenice, Bernice, Bonita, Bonnie, Bunny, Fannie, Fanny, Frances, Francesca, Francesco, Francine, Francis, Francisco, Frank, Frankie (USA)

Today is Also…

Day of Year: Day 277 of 2024; 88 days remaining in the year

ISO: Day 3 of week 40 of 2023

Celtic Tree Calendar: Gort (Ivy) [Day 2 of 28]

Chinese: Month 8 (Xin-You), Day 20 (Yi-Wei)

Chinese Year of the: Rabbit 4721 (until February 10, 2024)

Hebrew: 19 Tishri 5784

Islamic: 19 Rabi I 1445

J Cal: 7 Shù; Sevenday [7 of 30]

Julian: 21 September 2023

Moon: 70%: Waning Gibbous

Positivist: 25 Shakespeare (10th Month) [Beethoven]

Runic Half Month: Gyfu (Gift) [Day 8 of 15]

Season: Autumn (Day 11 of 89)

Zodiac: Libra (Day 11 of 30)

0 notes

Text

Holidays 10.4

Holidays

Blessing of the Animals at the Cathedral Day

Cable Street Day (UK)

Carrying in the Pudding (London, UK)

Ctenophore Day

Day of Peace and Reconciliation (Mozambique)

Day of the Space Forces (Russia)

Dick Tracy Day

eDay (New Zealand)

Forever Alone Day

Get Your Friend Day

Global Work From Home (WFH) Day

Golf Lovers Day (a.k.a. National Golf Day)

Hug a Non-Meat Eater Day

Improve Your Office Day

International Dakota Johnson Day

International No Disposable Cup Day

International Sputnik Day

International Toot Your Flute Day

International Walk & Bike to School Day

International Wound Hygiene Day

International Zookeeper Day

Kids Music Day

Kindness to Animals Day

National CB Radio Day

National Clothespin Day

National COVID-19 Remembrance Day

National Day of Action for Missing & Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls & Two-Spirit People (Canada)

National Day of Chilean Music (Chile)

National Day of Life (Colombia)

National 4-H Spirit Day

National Laura Day

National Ship in a Bottle Day

National Side Bae Day

National Sisters in Spirit Day (Canada)

National Talk Like a Trucker Day

National Teach German Day

National Trucker’s Appreciation Day

Peace and Reconciliation Day (Mozambique)

See the Light Day

Snoopy Day

Territory Day (Christmas Island)

Thanksgiving Day (Saint Lucia)

Thimpu Tsechu (Bhutan)

Ten-Four Day

What’s the Frequency, Kenneth? Day

Winter Squash Day (French Republic)

World Animal Day

World Day of Bullying Prevention

World Dyslexia Day

World Pet’s Day

World RBD Day

Food & Drink Celebrations

Canadian Beer Day

Cinnamon Roll Day (Finland)

Kanelbullens Dag (Cinnamon Bun Day; Sweden)

National Frappe Day

National Taco Day

National Vodka Day

Sardines Day (Japan)

1st Wednesday in October

Balloons Around the World Day [1st Wednesday]

California Clean Air Day (California) [1st Wednesday]

Canadian Beer Day (Canada) [Wednesday before 2nd Monday]

Children’s Day (Chile) [1st Wednesday]

Energy Efficiency Day [1st Wednesday]

International Walk to School Day [1st Wednesday]

National Coffee with a Cop Day [1st Wednesday]

National Kale Day [1st Wednesday]

National Pumpkin Seed Day [1st Wednesday]

Nottingham Goose Fair begins (UK) [1st Wednesday thru Sunday]

Random Acts of Poetry Day [1st Wednesday]

Semana Morazánica begins (Honduras) [1st Wednesday]

Walk Maryland Day (Maryland) [1st Wednesday]

World Financial Planning Day [1st Wednesday]

Independence Days

Belgium (from the Netherlands, 1830)

Lesotho (from UK, 1966)

Feast Days

Amun (a.k.a. Ammon; Christian; Saint)

Aurea (Christian; Saint)

Beethoven (Positivist; Saint)

Buster Keaton Day (Church of the SubGenius; Saint)

Chong Yeung Festival (Festival of Ancestors; Macau)

David & Dickory (Muppetism)

Double Ninth Festival (China) [9th day of 9th Lunar month]

Edwin, King of Northumberland (Christian; Saint)

Elder’s Day (China) [9th Day of 9th Lunar Month]

Feast of Hathor (Egyptian God of Drunkenness)

Fortified Wines Day (Pastafarian)

Francesco Solimena (Artology)

Francis of Assisi (Christian; Saint)

Frederic Remington (Artology)

Ieiunium Cereris (Fast of Ceres; Ancient Rome)

Jean-François Millet (Artology)

Jejunium Cereris (Feast for Demeter; Pagan)

Lucas Cranach the Younger (Artology)

Marcus and Marcian (Christian; Martyrs)

Martyrs of Triers (Christian; Saint)

Petronius of Bologna (Christian; Saint)

Lucky & Unlucky Days

Prime Number Day: 277 [59 of 72]

Sakimake (先負 Japan) [Bad luck in the morning, good luck in the afternoon.]

Unfortunate Day (Pagan) [46 of 57]

Unlucky Day (Grafton’s Manual of 1565) [46 of 60]

Premieres

ABC After School Specials (TV Series; 1972)

All the Right Reasons, by Nickelback (Album; 2005)

An American in Paris (Film; 1951)

The Batman Superman Movie: World’s Finest (WB Animated Film; 1997)

Beverly Hills 90120 (TV Series; 1990)

Bound (Film; 1996)

Bridge of Spies (Film; 2015)

Commando (Film; 1985)

Dolemite Is My Name (Film; 2019)

The EGGcited Rooster (WB MM Cartoon; 1952)

Encyclopedia Brown, Boy Detective, by Donald J. Sobol (Novel; 1963)

Extraordinary Machine, by Fiona Apple (Album; 2005)

Gravity (Film; 2013)

Is You Is Or Is You Ain’t My Baby, by Louis Jordan (Song; 1943)

Joker (Film; 2019)

Knight Templar, by Leslie Charteris (Novel; 1930) [Saint #4]

The Last Emperor (Film; 1987)

Leave It To Beaver (TV Series; 1957)

The Longest Day (Film; 1962)

Lost Horizon, by James Hilton (Novel; 1933)

The Man in the High Castle, by Philip K. Dick (Novel; 1962)

The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays, by Albert Camus (Essays; 1942)

Neon Genesis Evangelion (Japanese Anime; 1995)

Notes on Democracy, by H.L. Mencken (Political Book; 19

The Thing You Do (Film; 1996)26)

The Saint, starring Roger Moore (TV Series; 1962)

Trick or Treat Scooby-Doo! (WB Animated Film; 2022)

200 Motels, by Frank Zappa & The Mothers of Invention (Soundtrack Album; 1968)

Walls & Bridges, by John Lennon (Album; 1974)

Today’s Name Days

Aurea, Edwin, Franz (Austria)

Franciska, Franjo, Franka (Croatia)

František (Czech Republic)

Franciscus (Denmark)

Randel, Rando, Randolf, Ranno (Estonia)

Frans, Saija, Saila (Finland)

Aure, Bérénice, François, Frank, Orianne, Sarah (France)

Aurora, Edwin, Emma, Franz, Thea (Germany)

Ierotheos, Kallisthenis, Verina (Greece)

Ferenc (Hungary)

Francesco, Petronio (Italy)

Francis, Modra, Zaigonis (Latvia)

Eivydė, Mąstautas, Pranas, Pranciškus (Lithuania)

Frank, Frans (Norway)

Edwin, Franciszek, Konrad, Konrada, Manfred, Manfreda, Rozalia (Poland)

Ierotei (Romania)

František (Slovakia)

Francisco (Spain)

Frank, Frans (Sweden)

Damara, Damaris, Berenice, Bernice, Bonita, Bonnie, Bunny, Fannie, Fanny, Frances, Francesca, Francesco, Francine, Francis, Francisco, Frank, Frankie (USA)

Today is Also…

Day of Year: Day 277 of 2024; 88 days remaining in the year

ISO: Day 3 of week 40 of 2023

Celtic Tree Calendar: Gort (Ivy) [Day 2 of 28]

Chinese: Month 8 (Xin-You), Day 20 (Yi-Wei)

Chinese Year of the: Rabbit 4721 (until February 10, 2024)

Hebrew: 19 Tishri 5784

Islamic: 19 Rabi I 1445

J Cal: 7 Shù; Sevenday [7 of 30]

Julian: 21 September 2023

Moon: 70%: Waning Gibbous

Positivist: 25 Shakespeare (10th Month) [Beethoven]

Runic Half Month: Gyfu (Gift) [Day 8 of 15]

Season: Autumn (Day 11 of 89)

Zodiac: Libra (Day 11 of 30)

0 notes

Text

Indigenous rights advocates in Canada and the United States have renewed longstanding calls for concrete action to stem disproportionate rates of violence against Indigenous women and girls in both countries.

Thursday marks Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons Awareness Day in the US, while it is the National Day of Awareness for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG), otherwise known as Red Dress Day, in Canada.

“The Federal Government has an obligation to ensure that cases of missing or murdered persons are met with swift and effective action,” US President Joe Biden said in a proclamation recognising the day.

“My Administration is fully committed to investigating and resolving these cases through a coordinated law enforcement response, as well as intervention and prevention efforts. We are also dedicated to researching the underlying causes of this violence and to working with Native communities to address them,” Biden said.

Indigenous communities have sounded the alarm for years over the disproportionately high number of women, girls and two-spirit people who have been killed or disappeared in the US and Canada. Two-spirit is a term used by some Indigenous people to describe their gender and spiritual identity.

Advocates also have denounced systemic inaction on the part of government and law enforcement agencies to address the issue.

In 2014, the federal Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) reported that nearly 1,200 Indigenous women had been murdered or gone missing in Canada between 1980 and 2012 – but advocates say the real number was likely much higher.

A National Inquiry on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls in 2019concluded that the violence “amounts to a race-based genocide of Indigenous Peoples” that especially targets women, girls and members of the LGBTQ2S+ community.

“This genocide has been empowered by colonial structures … leading directly to the current increased rates of violence, death, and suicide in Indigenous populations,” it said.

But Indigenous community advocates say too little has been done to address the problem.

“Almost three years after the National Inquiry into #MMIWG released their Final Report, we are still waiting on the concrete actions that must be taken outlined in the Calls for Justice,” Lynne Groulx, CEO of the Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC), said on Twitter on Thursday.

In the US, the National Crime Information Center in 2016 documented 5,712 reports of missing American Indian and Alaska Native women and girls, according to a report by the Urban Indian Health Institute (PDF).

“The Center[s] for Disease Control and Prevention has reported that murder is the third-leading cause of death among American Indian and Alaska Native women and that rates of violence on reservations can be up to ten times higher than the national average,” the report also said.

A 2016 study by the National Institute of Justice also found that 84.3 percent of American Indian and Alaska Native women have experienced violence in their lifetime, including 56.1 percent who have experienced sexual violence, the US Department of the Interior says on its website.

US interior secretary Deb Haaland, the first Indigenous person to head a cabinet agency in the history of the country, held an event on Thursday to recognise National Missing or Murdered Indigenous Persons Awareness Day.

“Everyone deserves to feel safe in their community, but a lack of urgency, transparency and coordination have hampered our country’s efforts to combat violence against American Indians and Alaska Natives,” Haaland, a member of the Laguna Pueblo tribe, said in a statement.

“As we work with the Department of Justice to prioritize the missing and murdered Indigenous people’s crisis, the Not Invisible Act Commission will help address the underlying roots of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Peoples crisis by ensuring the voices of those impacted by violence against Native people are included in our quest to implement solutions.”

The US Congress signed the Not Invisible Act into law in October 2020, just months before Biden took office, and the commission aims to increase coordination and implement best practices to fight “the epidemic of missing persons, murder, and trafficking” affecting Indigenous communities.

In Canada, communities are hanging red dresses on Thursday to symbolise the many Indigenous women and girls who have gone missing or been murdered in the past decades.

“I’m wearing red on #RedDressDay to remember all the #MMIWG and to honour their families and communities. I’m wearing red also because I continue to hold a vision of the future where our women and girls are protected and treated with dignity and respect always,” RoseAnne Archibald, national chief of the Assembly of First Nations in Canada, tweeted.

“On May 5, we will see the red dresses suspended from trees, hanging from windows, swaying in the breeze. But we will see much more than that. We will see the people who would have worn those crimson garments,” Lorraine Whitman, president of NWAC, said in a statement this week.

“They were our mothers, our daughters, our sisters, our aunties, our friends … We want to know what happened. How were they taken from us? And why? But mostly, we want to know that other families will be spared this pain.”

#May 5th is National Day of Awareness for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG#RedDressDay

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

October 4 was the National Day of Action for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. I stopped in to the vigil at All Saints’ Anglican Cathedral. Pictured is the Ven. Travis Enright, Archdeacon for Indigenous Ministries, Chubby Cree, and Michelle Nieviadomy, one of the poets who presented. I had to leave early because it was Kol Nidre night (beginning of Yom Kippur), but there was a good turnout and a great program planned. #yeg #yegdt #mmiwg #indigenous #yegwomen #stolensisters #sistersinspirit (at All Saints' Anglican Cathedral, Edmonton) https://www.instagram.com/p/CjYDgSyrKUn/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

Correctional services, both institutional and within the community, are impacted by COVID-19. In the current paper, we focus on the current situation and examine the tensions around how COVID-19 has introduced new challenges while also exacerbating strains on the correctional system. Here, we make recommendations that are directly aimed at how correctional systems manage COVID-19 and address the nature and structure of correctional systems that should be continued after the pandemic. In addition, we highlight and make recommendations for the needs of those who remain incarcerated in general, and for Indigenous people in particular, as well as for those who are serving their sentences in the community. Further, we make recommendations for those working in closed-custody institutions and employed to support the re-entry experiences of formerly incarcerated persons. We are at a critical juncture—where reflection and change are possible—and we put forth recommendations toward supporting those working and living in correctional services as a way forward during the pandemic and beyond.

Note from the authors

In the current policy briefing, we use the terms “imprisoned people” and “incarcerated persons” because this terminology is less stigmatizing than terms such as “inmates” or “prisoners”. We are restricting the current policy brief to recommendations concerning prison living and post-prison living in an era of “decarceration”, which refers to reducing the size of the incarcerated population. We recognize that decarceration includes alternatives to imprisonment such as pretrial diversion practices or alternatives introduced at the back and front-end of sentencing, which are largely beyond the scope of the current brief.

We also recognize that there are many marginalized and vulnerable populations in prison, including: women, people with mental health disorders or needs and substance use challenges, persons with brain injuries, persons with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome Disorder and other health-related conditions, transgender and non-binary self-identifying persons, and other equity-seeking groups. It is beyond the scope of the current brief to attend to the complexity of each groups’ needs and unique positioning in detail. For instance, while the needs of incarcerated Black Canadians and people of colour are important and worthy of attention, we chose to focus on the inequities of incarcerated Indigenous Peoples, because this group has the highest rates of incarceration for any sub-population in Canada (see “Indigenous persons in prison” section) and the robust empirical data on Indigenous Peoples in Canada and existing policy-oriented documents details their unique needs, such as the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s “Calls to Action”. We intend to address some of the unique needs of diverse populations in future policy briefings. The present brief is a starting point to highlight recommendations for various pressing issues, as evidenced during the trials and tribulations imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. As researchers, we are committed to provide evidence-informed recommendations.

Introduction

In the days following 12 March 2020, when the World Health Organization declared Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) a pandemic, the Canadian provinces and territories began imposing strict lockdown measures. These governments recognized closed-custody correctional facilities, including prisons, correctional centres, and jails, as potentially high-risk for the transmission of COVID-19, despite confusion about how best to manage the virus in prisons (and other confined spaces). On 12 March 2020, the Union of Canadian Correctional Officers (UCCO-SACC-CSN), representing federal correctional officers employed by Correctional Service Canada (CSC), requested support from CSC to help ensure the health and safety of their members during the pandemic (UCCO-SACC-CSN 2020). Of course, it is not only the physical health risk posed by the novel virus that creates distress; researchers are finding that the mental health effects of COVID-19 are dire, as isolation and quarantine are having undeniable effects on people’s social and mental health (del Rio and Malani 2020; Rajkumar 2020; Torales et al. 2020; Xiong et al. 2020). The World Health Organization defines “health” as a having three facets—social, physical, and mental health—and urges us to recognize each as nonhierarchical components of health and as having a significant effect on people’s overall health (World Health Organization 2020).

In the spring of 2020, CSC reported several in-prison outbreaks of COVID-19 that affected both those housed and working in prison. Provincial and territorial institutions took urgent measures in response to the pandemic, such as decreasing the prison population by releasing those that were eligible (Statistics Canada 2020a, 2020b). Federal prisons also took steps to manage the virus by suspending visits and programming, imposing lockdowns, distributing personal protective equipment (PPE), and introducing additional measures for containing, testing, and detecting COVID-19. Altogether, COVID-19 and the institutional responses have affected the social, physical, and mental health of those housed in and employed by prisons.

By early November 2020, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) updated COVID-19 guidelines to account for the risk posed by aerosol transmission of the virus (Miller 2020). Such a change is particularly important given public health measures informing that physical distancing alone, which is already near impossible in prison, does not adequately protect incarcerated persons from aerosol transmission, which requires well-ventilated spaces when indoors. Incarcerated persons sleep, eat, shower, use the washroom, and exercise, among other activities, in close proximity to other incarcerated persons, officers, and staff in often poorly ventilated prison spaces (Ricciardelli 2014b)—making aerosol transmission particularly concerning.

Officers and staff bear the status of essential service providers and now “face an unprecedented, ongoing challenge” if they are to limit (and manage) the spread of COVID-19 in prisons (Ricciardelli and Bucerius 2020). Staff and officers must balance staying safe and healthy while maintaining the care, custody, and control of incarcerated persons as well as striving not to infect their family members and friends or bringing COVID-19 into the institution. In some cases, despite an outbreak of COVID-19 in the correctional institution, correctional officers working in some provincial systems are asked to continue coming into work when COVID-19 outbreaks happen and to otherwise isolate when not working (Herring 2020). To this end, in Canada and abroad, COVID-19 “represents a serious threat to the health and welfare of people who live and work in these facilities” (Pyrooz et al. 2020, np, see also Kinner et al. 2020; Stephenson 2020).

Infectious disease is not a new concern in prison. About one-quarter of new correctional officer recruits, some with and some without prior correctional work experience, indicated (without being asked) that infectious disease was their biggest fear of working in a correctional institution (R. Ricciardelli, unpublished data). These findings predate the novel coronavirus and the possibility of airborne transmission, with interviewees reporting fears of hepatitis, HIV, and tuberculous. The COVID-19 pandemic imposes additional stress on a subpopulation already concerned about contagion, likely impacting officers’ well-being and mental health.

There are several factors that influence how easily COVID-19 can be introduced and spread in correctional institutions, including: the daily intake of incarcerated people in provincial and territorial systems, the movement of staff in and out of institutions, the physical layout and size of the respective prisons, shorter sentences (leading to potentially higher turnover rates), the use of holding cells for newly admitted people, and the demographic makeup and health conditions of the incarcerated population. However, empirical evidence in support of one of more of these explanations for COVID-19 infections in correctional settings is lacking. It is possible that the correlates of COVID-19 infection in non-institutionalized settings to not translate to institutionalized settings like jails and prisons.

As of 7 January 2021, in the federal correctional system, 1201 incarcerated persons had tested positive for COVID-19 in penitentiaries across the country, of which three incarcerated people had died (Correctional Service Canada 2020). At least in part, the more recent escalation in numbers can be attributed to the introduction of rapid testing in federal prisons. UCCO-SACC-CSN confirmed that, as of 4 November 2020, 123 federal correctional officers had tested positive (Robertson 2020). The provincial systems too have been impacted by multiple outbreaks. For instance, as of 31 October 2020, 104 of the 161 incarcerated people in the Calgary Correctional Centre had tested positive, comprising 65% of the population housed in prison, as well as 20 staff and officers (Bruch 2020). In Manitoba, at Headingley Correction Centre, 86 incarcerated persons and 24 staff and correctional officers had tested positive as of 3 November 2020 (Unger 2020). Administrators, advocates, and journalists continue to report outbreaks across the country, including at institutions such as the Saskatoon Correctional Centre and Grand Valley Institution (CBC News 2020; Ghonaim 2020). In Canadian federal penitentiaries, some facilities reported outbreaks in the early months after the virus first spread to Canada (i.e., Mission Institution in British Columbia and the Multi-level Federal Training Centre in Quebec, or more recently in Stoney Mountain Institution), with additional outbreaks following during wave two of the pandemic.

As we step out in these new and unprecedented times, we put forth considerations and associated recommendations that look to the present and future of correctional services in Canada. In doing so, we will focus on (i) recommendations that directly pertain to the current pandemic and how to best address COVID-19 related concerns in correctional systems, yet (ii) also make recommendations for people working and housed in prison now and beyond the pandemic. In the current policy brief, we provide evidence-informed recommendations for correctional services across systems in four key areas:

decarceration;

the needs for those remaining in our institutions, albeit working, living, visiting or volunteering;

Indigenous persons in prison; and

the needs of community corrections to support current parole/probation as well as future decarceration efforts.

Context and histories of criminalized persons in Canada

Canada houses individuals charged or convicted of crimes in one of fourteen unique but interconnected correctional systems: (i) the federal system known as the CSC or (ii) one of 13 different provincial and territorial systems, each governed by their own provincial or territorial Ministry or Department overseeing correctional services (e.g., Justice, Public Safety). The main difference between the federal and provincial–territorial systems is sentence duration and remand status (e.g., persons housed in prison awaiting trial or sentencing). CSC houses individuals convicted of a crime and sentenced to two or more years in prison, in institutions of diverse security classification that range from minimum (e.g., no secure perimeter) to maximum (e.g., very secure parameter) (Ricciardelli 2014b). In 2015–2016, correctional institutions in Canada housed an average of approximately 40 000 adults per day, representing a national incarceration rate of 139 per 100 000 individuals (Reitano 2017). People housed in federal institutions account for a smaller number of incarcerated persons in comparison to the provincial and territorial systems, for instance in 2017–2018 “on a typical day” 14 015 individuals were housed in one of over 50 federal penitentiaries (Correctional Service Canada 2019). Generally, after serving one-third of a federal sentence, a federally incarcerated person may be eligible for parole or for statuary release after serving two-thirds of their sentence.

The provincial and territorial correctional systems house the majority of incarcerated persons in Canada. Collectively, they oversee appropriately 177 closed-custody institutions (e.g., prisons, correctional centres, and jails) that confine individuals who are either sentenced to a prison term of two years less one day or remanded into custody. Since 2004–2005, remanded people constituted the majority of the provincial and territorial custodial population (Manitoba Government and General Employees’ Union February 9, 2012; Porter and Calverley 2011; Statistics Canada 2017b). For example, on an “average day” in 2014–2015, more adults were housed in prison awaiting trial than convicted individuals serving a sentence in custody. Specifically, in the provincial and territorial systems, of the 24 014 adults per day on average in sentenced custody and pretrial detention, 13 650 (57%) were incarcerated pretrial (Statistics Canada 2017b). Remand facilities housing incarcerated persons (i.e., jails, detention centres, and correctional centres) operate as maximum-security institutions. Although individuals remanded into custody are legally presumed innocent, they are held awaiting trial in custody, rather than the community, because they are unable to secure bail either for being considered a flight risk, a threat to the public in terms of posing a substantial likelihood to offend, or otherwise unable to satisfy basic bail requirements (e.g., lacking a surety) (Deshman and Myers 2014). After serving a portion of their sentence in custody, provincially and territorially sentenced individuals are eligible for probation.

The overwhelming majority of people enter prison with some degree of vulnerability. Incarcerated persons are likely to lack employment experience and educational attainment and often suffer from compromised mental health or challenges with substance misuse or addiction. Many incarcerated people have experienced periods of homelessness in their lives and the vast majority have experienced childhood trauma in the form of physical and sexual abuse (Bucerius et al. 2020a) and changing caregiver situations (Bucerius 2020). At the provincial level, Bucerius et al. (2020b) found that 88% of male participants and 84% of female participants identified having experienced violent victimization (e.g., hitting, getting beaten up, had weapons used against them, etc.) at some point in their lives, with a mean age of the first violent victimization that male participants could recall being 14 years, and female participants 17 years of age. In total, 34% of their male participants had experienced some form of sexual victimization (e.g., unwanted touching and sexual assault) during their lives, with a mean age of first sexual victimization for men being 7.4 years old. In total, 75% of the female sample had experienced sexual victimization, with the first victimization occurring at an average age of 9.9 years old. At the federal level, these numbers are even higher, with the great majority having experienced physical and (or) sexual abuse long before being first charged with a crime (95% of all federally sentenced women and 87% of all federally sentenced men) (Bucerius 2020). These data reflect that people housed in prison experience victimization at much higher rates than the general population in Canada. Data from the General Social Survey (GSS) (N = 33 089) reported that 32.8% of Canadian men and 22.9% of Canadian women had experienced violent victimization before the age of 15. In terms of sexual victimization, 4.6% of Canadian men and 13.2% of Canadian women have been sexually victimized prior to the age of 15 (Statistics Canada 2016).

People housed in prison are also at a disadvantage when it comes to educational attainment. At the federal level, CSC reports that between 1995 and 2005, eight in every 10 persons admitted to federal custody did not have a high school diploma. Moreover, upwards of 20% of new federal admissions had less than a grade eight education (Boe 2005). The statistics are in dramatic contrast to 14% of the Canadian population aged 25 or older who, in 2016, reported less than a high school diploma as their highest educational level (Uppal 2017). Beyond entering prison under-educated, periods of incarceration severely limit a person’s ability to develop a history of employment or to develop marketable skills that would support later reintegration (Graffam et al. 2004; Atkin and Armstrong 2013). Disadvantages become more pronounced for persons whose first experience of incarceration was during their youth or young adulthood—the period in which invaluable apprenticeship, educational, and training opportunities are highly consequential (Nagin and Waldfogel 1995). Incarcerated persons are more likely to have lower than average levels of literacy and numeracy and to lack job skills, interpersonal skills, social competencies, technological literacy, and prior work experience in comparison to the general population (Waldfogel 1994; Fletcher 2001; Nally et al. 2011; Decker et al. 2014; Young 2017).

Internationally, rates of infectious disease, chronic diseases, and mental health disorders are higher among incarcerated persons than in the general population (Harris et al. 2007;Wilper et al. 2009; Fazel and Baillargeon 2011; Stewart et al. 2014). Simply said, persons enter prison with poor baseline health. In Canada, Beaudette et al. (2015) reported that the lifetime prevalence of any mental disorder among men newly admitted to CSC ranged from 78% to 88% across regions and the prevalence of a current mental health disorder among these same men ranged from 68% to 82% (see also Stewart et al. 2017). Yet, in the general Canadian population, diagnosed mental disorder prevalence rates remain around 10% (Statistics Canada 2018). Looking at the prevalence of mental disorders among 154 women incarcerated in six CSC facilities, Brown et al. (2018) found that almost 80% of federally sentenced women in custody “meet the criteria for a current mental disorder, including high rates of alcohol and substance use, antisocial personality disorder and borderline personality disorder” (p. iii). In addition, almost two-thirds of their sample reported a major mental disorder over their lifetime and 17% a current major mental disorder.

Formerly incarcerated persons, in comparison to the general population, are more likely to have mental health needs, ranging from substance dependence to neurological or psychiatric needs to broader health issues (e.g., poor diet and smoking) (Graffam et al. 2004). Drawing from a sample of 2273 newly admitted adult male federally incarcerated persons in Canada, Stewart et al. (2014) determined that these men most commonly report the health conditions of head injury (34.1%), asthma (14.7%), and back pain (19.3%). Nolan and Stewart (2014) found that the most common cited health concerns among 280 newly admitted adult women incarcerated persons included back pain (26%), head injury (23%), hepatitis C virus (19%), and asthma (16%). Overall, incarcerated people tend to enter prison in already poor health and are met with in-prison health care and nutrition that requires careful evaluation to ensure that health conditions improve or, at least, do not worsen.

Decarceration

Many provincial and territorial prisons are currently housing fewer people in an effort to reduce prison populations during the COVID-19 pandemic (CBC News 2020; Cousins 2020; Statistics Canada 2020a). Organizational responses also include early release and reducing arrests, jail bookings, and admissions (also tied to temporary court closures or delays). We define decarceration as alternatives to incarceration, such as serving sentences in the community rather than in prison, as well as the premature conclusion of a criminal sentence, and the aggregate reduction in the prison population. Decarceration efforts have been rarer at the federal level (see, for example, Quan 2020), where incarcerated persons are serving longer sentences and have more distant eligibility dates for statuary release (i.e., incarcerated persons are eligible after serving two-thirds of a federal sentence) or parole (i.e., eligibility commences after servicing one third of a federal sentence).

Decarceration is increasingly necessary, especially during the current pandemic. Imprisonment is an expensive and often ineffective means of dealing with crime and public safety, and generally damages the well-being and life chances of those who are subjected to it, such as by severing ties to family members and employment opportunities. Imprisonment also has well-documented collateral consequences, such as how incarceration affects the children of people who are incarcerated (Murray and Farrington 2008; Turney and Wildeman 2013; Wakefield and Wildeman 2013). The link between crime and imprisonment is highly complex, meaning that changes in imprisonment rates are generally thought to have relatively little impact on rates of crime (see, for example, DeFina and Arvanites 2002; Carter 2003). In countries—such as Finland—where deliberate efforts have been made to reduce their prison populations, the evidence does not suggest an associated increase in crime rates (Lappi-Seppälä 2009).

The nature, scope, and structure of decarceration must take into account the circumstances, positioning, and needs of the incarcerated people—particularly in relation to their own safety and well-being, while balancing this with public safety. Decarceration efforts must be geared toward meeting the needs of incarcerated people (i.e., does the person who transgressed the law, even if 10, 15, or even 20 years ago, present the same threat to public safety today? What about months or weeks later post-offense?), the seriousness of the offense and potentiality for recidivism or desistance from crime, and their security classifications within the system. Providing individuals with the community supports and services that would allow them to be released and re-enter the community in a safe and humane way (e.g., ensuring that individuals have access to safe housing options, crisis counselling, etc.) seems like the “better” option than continued imprisonment.

To this end, any release planning must be informed by an individual’s history and their own views of their life, past and present, and future plans; in other words, release planning must be desistance focused. In addition, the process of releasing a person from prison must realistically assess the threat posed by the person to society and the threat society poses to the person who is being released. Considering personal safety measures and processes of rehabilitation or recovery at play in prison, care and safe housing must be assured before releasing a person during COVID-19, as should the continuation of any rehabilitative interventions from which individuals feel they are deriving benefit. The resting assumption that everyone housed in prison prefers release may ignore the individual’s perspective as researchers have demonstrated that prison can—tragically—serve as a space of temporary refuge for some incarcerated people (Bucerius et al. 2020a; Pyrooz et al. 2020). Improving the quality of various forms of welfare provision within society (e.g., housing, mental health services, refuges for victims of abuse, and drug detoxification) would reduce the likelihood of citizens regarding prisons as more positive environments than the free community. To this end, effort should be made to provide individuals with the community supports and services that would allow them to be released and re-enter the community in a safe and humane way, so that people are not put in a position where the prison seems like the “better” option.

To facilitate decarceration at all levels of the prison system, stakeholders and administrators must assess and critically examine the decarceration of halfway houses and other temporary housing spaces. Governments must closely examine the cases of those living in such facilities, recognizing who may be psychologically, socially, and physically ready for complete and successful reintegration into the community (i.e., to leave the halfway house). The release of incarcerated persons from halfway houses frees up existing space in halfway houses for persons leaving prison.

Decarceration, however, “is a process, not a one-time action” (Wang et al. 2020, pp. S-3). To this end, our recommendations include immediate actions geared toward decarceration and, given the uncertain nature of the pandemic and its duration, longer-term actions for implementation. We also advocate for equity in decarceration efforts, referring specifically to ensuring all people inside prisons are considered for early release. Equity is particularly important in relation to incarcerated Indigenous Peoples, who are disadvantaged at every stage of the criminal justice system, including when it comes to parole decisions and re-entry (Cardoso November 29 2020).

Recommendations for decarceration across systems

1. Review the release status of all persons housed in prison, remanded or sentenced, both provincially–territorially and federally, in a fair and equitable manner that accounts for personal and criminal histories, for the purpose of releasing prisoners. We recommend that stakeholders apply a culturally informed lens, that includes but is not limited to histories of racial inequalities, to understand individual actions within the context of a person’s actual potential for successful release. When re-evaluating the release status, the guiding question should be whether the person can safely be reintegrated and will likely not pose harm to the broader community.