#crime and punishment in canada

Text

Nova Scotia Justice Minister Brad Johns has resigned, according to a short statement from Premier Tim Houston on Friday evening.

“I accepted the resignation of Brad Johns as a minister in my cabinet,” read the statement.

Speaking to reporters Thursday, the fourth anniversary of the beginning of the Nova Scotia mass shooting, Johns told reporters he didn’t believe domestic violence was an “epidemic.”

“No, I don’t because I think epidemic…you’re seeing it everywhere all the time,” Johns said. “I don’t think that’s the case. Personally I think this was an issue and is an issue.”

When pressed, he said he believed there were other issues causing more problems in society such as drugs and guns. [...]

Continue Reading.

Tagging: @newsfromstolenland

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Scene girl of Rodion Raskolnikov from Crime and Punishment by Dostoyevsky, drawn in MSPaint with effects from PicMix

#scene#2000s scene#emo scene#scene aesthetic#scene art#emo#2000s emo#emo art#emo as hell#emo kid#crime and punishment in canada#fyodor dostoevsky

404 notes

·

View notes

Text

Succumbing to illness (Stress sick) while stewing over the guilt of my sins (math test I didn't study for), yearning for repentance while knowing deep down it was my duty to do this; that no one will suffer from my actions, rather, prosper together because of it (didn't study because I was having good snacks with my friend). Should the public find out what I've done (my parents), surely they'll understand how juvenile my sins were rather than the presumed monstrosities.

#every classic lit character ever#victor frankenstein#rodion romanovich raskolnikov#crime and punishment in canada#mary shelly's frankenstein#i need to take my meds#help girl im a sick victorian child

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

#vintage#80s#grunge#retro#al pacino#the godfather#artists on tumblr#raskolnikov#crime and punishment in canada#crime and punishment fanart#dostoevksy#fyodor dostoevsky#devil may cry

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

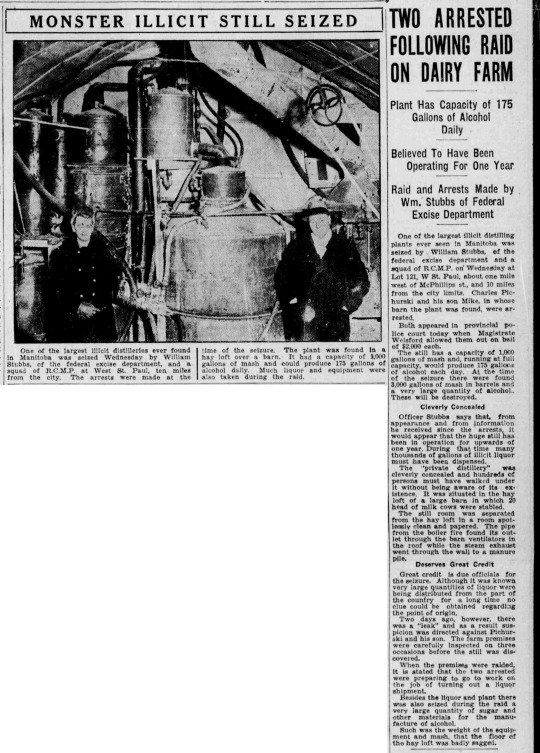

“HUGE ILLICIT STILL SEIZED AT WEST ST. PAUL,” Winnipeg Tribune. December 29, 1932. Page 1.

----

TWO ARRESTED FOLLOWING RAID ON DAIRY FARM

---

Plant Has Capacity of Gallons of Alcohol Daily

----

Believed To Have Been Operating For One Year

---

Raid and Arrests Made by Mr. Stubbs of Federal Excise Department

----

One of the largest illicit distilling plants ever seen in Manitoba was seized by William Stubbs of the federal excise department and a squad of R. C. M. P. on Wednesday at Lot 121, W St. Paul, one mile west of McPhillips St., and 10 miles from the city limit. Charles Pichurski and his son Mike, in whose barn the plant was found, were arrested.

Both appeared in provincial police court today when Magistrate Welsford allowed them out on ball of $2,000 each.

The still has a capacity of 1,0000 gallons of mash and running at full capacity would produce gallons of alcohol each. At the time of the seizure there were found 3,000 gallons of mash in barrels and a very large quantity of alcohol. These will be destroyed.

Cleverly Concealed

Officer Stubbs says that, from appearance and from information he received since the arrests, it would appear that the huge still has been in operation for upwards of one year. During that time, many thousands of gallons of Illicit liquor must have been dispensed.

The ‘private distillery’ was cleverly concealed and hundreds of persons must have walked under it without being aware of its existence. It was situated in the hay loft of a large bam in which 20 head of milk cows were stabled.

The still room was separated from the hay loft in a room spotlessly clean and papered. The pipe from the boiler fire found its outlet through the barn ventilators in the roof while the steam exhaust went through the wall to a manure pile.

Deserves Great Credit

Great credit is due officials for the seizure. Although it was known very large quantities of liquor were being distributed from the part of the country for a long time no clue could be obtained regarding the point of origin.

Two days ago, however, there was a ‘leak’ and as a result suspicion was directed against Pichurski and his son. The farm premises were carefully inspected on three occasions before the still was discovered.

When the premises were raided, it is that the two arrested were preparing to go to work on the job of turning out a liquor shipment.

Besides the liquor and plant there was also seized during the raid a very large quantity of sugar and other materials for the manufacture of alcohol.

Such was the weight of the equipment and mash, that the floor of the hay loft was badly sagged.

Photo caption:

MONSTER ILLICIT STILL SEIZED

One of the largest illicit distilleries ever found in Manitoba was seized Wednesday by William Stubbs, of the federal excise department, and a squad of R.C.M.P. at West St. ten miles from the city. The arrests were made at the time of the seizure. The plant was found in a hay loft over a barn. It had a capacity of 1,000 gallons of mash and could produce 175 gallons of alcohol daily. Much liquor and equipment were also taken during the raid.

#winnipeg#illicit still#excise department#moonshining#moonshine#liquor control#rural crime#rural canada#farming in canada#royal canadian mounted police#police raid#great depression in canada#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Resenha de "Crime e Castigo" de Fíodor Dostoiévski

*com alguns spoilers

Apesar de algumas passagens serem particulamente muito interessantes, não posso mentir e dizer que é um livro fácil ou entretível (essa palavra existe?)

A verdade é que estou feliz por ter iniciado minha jornada com Dostoiévski, mesmo quando eu não estava entendendo n a d a do que eu tava lendo eu me diverti demais

isso porque eu tava muito empolgada sabe, eu tava tipo "ok não tô curtindo por agora mas eu tenho certeza que vai melhorar depois☺"

Vi algumas resenhas no Skoob, e entendi perfeitamente o porquê de algumas pessoas não gostarem desse livro

A narrativa realmente é maçante, os personagens são aleatórios e a maioria é descartável e/ou desconexos com a proposta da história

o protagonista é desprovido de inteligência cognitiva, emocional e social, desprovido de sanidade mental e o pior de tudo: carisma

Pra mim o que faltou nesse livro foi carisma, foi o charme entendeu? Acho que se o livro fosse uma sátira, ele seria bem mais genial e muito mais interessante

Porque o protagonista é simplesmente uma grande piada. Não entra na minha cabeça como um ser humano poderia ser tão burro ao ponto de assassinar uma mulher pelo dinheiro dela, e depois não roubar nada dela (??????)

Eu também não entendi muito o intuito desse livro em geral sabe, eu acho que Dostoiésvski perdeu uma grande oportunidade com esse aqui. Pode ser um clássico e tal, mas ao mesmo tempo é um livro bem fraquinho

Como eu já falei aqui, às vezes as pessoas gostam de criar significados profundíssimos sobre coisas que na verdade são muito simples. E acho que isso acontece até demais aqui

Outro ponto que gostaria de ressaltar é que o maior dilema que eu tive lendo esse livro foi os nomes. Os nomes estranhíssimos que mudavam o tempo todo (chamaram o personagem principal de mais de 2 nomes diferentes e eu só fui me tocar que era ele, quando eu voltei para o préfácio) e a enorme quantidade de personagens me deixaram maluca

Eu não sabia mais quem era relevante e quem não era, foi uma loucura total e eu tenho certeza que uma parte da história passou direto pela minha cabeça só porque eu não consegui raciocinar os nomes de certos personagens e todo o papel deles na narrativa

Eu tive que parar de ler um pouquinho pra fazer um mapinha com todos os nomes e mesmo assim eu não entendi direito porque foi muita gente

Por fim o arco do romance, eu simplesmente odiei. Achei que não combinou e sinceramente foi bastante forçadinho porque dois malucos com um psicológico todo acabado não seriam um bom casal na minha humilde opinião. Qual a necessidade, eu pergunto

Não sei, você responde. Mas a verdade é que eu só terminei esse livro pesadão porque eu tinha muita força de vontade senão eu teria abandonado certeza

De toda forma, foi uma experiencia agridoce. Obrigado pela atenção, até a próxima

#book blog#book tumblr#resenha#resenha literária#livros#literatura#book review#leitura#bookworm#dica de livro#fyodor dostoevsky#dostoevksy#fyodor dostoyevsky bsd#dostoyevski#crime#crime e castigo#crime and punishment in canada#crime and punishment 1970#crime and punishment fanart#crime and punishment 2007#fiodor dostoievski#livros de romance#poesia

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading goals for the rest of the year:

Donna Tartt's novels in publication order (TSH, TLF and TG)

Hannah Arendt - Eichmann in Jerusalem

Fyodor Dostoevsky - Crime and Punishment

#the secret history#donna tartt#the little friend#the goldfinch#hannah arendt#crime and punishment in canada

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I have a new plan : to go mad”

— Dostoyevsky, letters of Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Artwork: Jason Walker

#beautiful quote#chekhov#lovecore#quotes#short story#dostoyevski#brothers karamazov#crime drama#crime and punishment in canada#leo tolstoy

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

It was a Sunday afternoon when Michael and his brother Jones decided to go by the local beach with the intent to break into people's cars to steal radios for resale. Although they have been caught multiple times by the police, they never stopped stealing because they had to meet ends. With their mom's addiction to meth and their dad missing from the picture, Michael and Jones had to figure out their life really fast.

However, that Sunday afternoon, things were about to take a different turn when the car they broke in had two teenage boys having sex.

Scared that the boys would report the incident to the cops, Jones held them at gunpoint, forced them to get dressed, and directed them to drive the car to an isolated area. Although Michael told his brother not to hurt the boys, Jones shot both boys once they were away from the populated beach area.

Jones undressed them with his brother's help upon killing the boys, dumped their bodies in a swamp nearby, put their clothes in the bag that they usually carry to put stolen goods, and drove away in the white el Camino.

Jones and Michael drove the stolen vehicle to a local bank following the killings. Although the reasons for going there are unclear, that specific Sunday afternoon, the two brothers had a dark cloud hanging over their heads with the grim reaper following them.

The two wore colored ski masks and broke into the local united bank, and robbed about $2,000 in cash.

As they fled the bank due to the alarm going off and alerting the authorities, Jones and Michael hit a pedestrian while trying not to get caught. Jones and Michael drove back to their residence with the stolen vehicle and stolen money.

Acting on a tip by a witness, the local police were able to apprehend the two brothers the following morning. They were celebrating with two prostitutes in the motel room where they were trying to lay low. Police recovered 20 unfired rounds of the 9mm ammunition from Jones's gun. In addition, clothing and other effects linked to the robbery were smoldering in the fireplace.

As the police questioned Jones And Michael about that Sunday's afternoon event, Michael, fearing the consequences for him and his brother's action, gave a voluntary statement describing the abduction and the killing of the victims in detail. Officers went to the scene of the murder and discovered the two murdered victims naked, with one of them missing a big chunk of his leg.

When initially interviewed by authorities, Jones and Michael admitted robbing the bank but denied kidnapping two boys or killing them. However, as Michael was getting more scared due to the allegations against his brothers and Him that were so accurate, He continued to deny any involvement in the murders, indicating that his brother had suggested the robbery. Finally, as the District Attorney's Office filed felony charges of auto theft, burglary, and manslaughter due to the hit and run, Michael, who was afraid of getting the death penalty, decided to explain everything to the police, including the two boys' murder.

On March 6, 1979, Robert Alton Harris was convicted in San Diego County, Superior Court of two counts of murder in the first degree with special circumstances and kidnapping. Thanks to his confession and genuine remorse, Michael was only convicted of kidnapping and sentenced to six years in state prison. He was discharged in 1999.

ON the other hand, things did not end up well for Jones, who showed no remorse. As a result, Jones was sentenced to the death penalty. He was executed in 2000 in the gas chamber at the State Prison. Jones requested and was given two large pizzas, a bucket of fried chicken, and ice cream for his last meal. Following Jone's execution, the body was removed from the chamber.

As Jones killed these two innocent boys, he did not know that he was also dancing with the grim reaper.

#book blog#book photography#books & libraries#booklr#true creepy stories#true crume#crime and punishment in canada

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

NOT MINE!!

#born to die#lily rose depp#lolitta#nympette#nymph3t#the bell jar#ultraviolence#alexa demie#coquette#dollette#fyodor dostoevsky#crime and punishment in canada#lana del rey vinyl#gaslight gatekeep girlboss#it girl#alanabc#alana champion

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Your worst sin is that you have destroyed and betrayed yourself for nothing.”

― Fyodor Dostoevsky, Crime and Punishment

#book quotes#fyodor dostoyevsky bsd#russian literature#classic lit quotes#inspirational quotes#self reflection#philosophy#crime and punishment in canada

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A new survey conducted by Research Co. found that the majority of Canadians support tying speeding tickets to income, otherwise known as “progressive punishment.”

According to the survey published on Friday, 65 per cent of Canadians surveyed endorse implementing progressive punishment for speeding tickets in their city. In addition24 per cent of respondents opposed the concept while 11 per cent are undecided.

Progressive punishment system has been implemented in some European countries such as Finland and Switzerland. Authorities in Finland set the fines on the basis of disposable income of the offending driver and how much speed the offending driver went over the posted limit. [...]

Continue Reading.

Tagging: @politicsofcanada

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Crime and Punishment: A Classic Masterpiece

Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment is a novel that has stood the test of time, and it is still relevant today. Published in 1866, the novel has since become a classic masterpiece and is considered one of the most influential works of literature in the 19th century. The novel is set in St. Petersburg, Russia, and follows the story of Rodion Raskolnikov, a young man who commits a crime and then struggles with his guilt and the consequences of his actions. The novel is a complex character study of Raskolnikov's mental state, and his inner turmoil is brilliantly portrayed....

Check out my blog in order to read the rest.

#crime and punishment in canada#crime and punishment#writing#writer#blog#blogger#writing blog#fyodor#fyodor dostoevsky#books#classic#classic books#books and literature#poetry blog#poetry

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I choose to imagine Raskolnikov, in his rot and misery, sat in a bar drinking a comically large strawberry milkshake

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

#fydor dostoevsky#crime and punishment in canada#quotes#life#people#love#quote#inspiring quotes#book quotes#daily life#life quotes#poetry love#crime and punishment

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

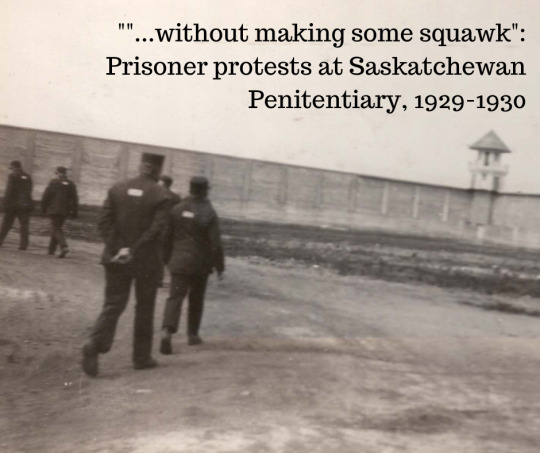

On November 14, 1929, a serious prison strike nearly broke out at the Saskatchewan Penitentiary in Prince Albert. Only by the narrowest of chances was the plot discovered by staff and the strike averted. The strike leaders were two convicts, Ashton and Jones, who referred to themselves in furtive notes as “sweethearts” and “lovers” - they dreamed of escaping to be together. Two hatchet-men from Ottawa were sent to clean up, senior officers of the penitentiary were dismissed, and the whole affair hushed up, save for a few stories in the newspapers. This is part of my rambling, fully informal, draft attempts to understand the origins and course and impact of the 1930s ‘convict revolt’ in Canada, and other issues related to criminality and incarceration Canadian history. (More here.)

Saskatchewan Penitentiary was, at the time, the newest federal penitentiary in Canada. Opened in 1911, to replace the territorial jail at Regina, parts of it were still under construction in 1929. UBC penologist C. W. Topping praised Sask. Pen as “the finest in the Dominion,” with supposedly ‘modern’ features in the cell-block and workshops, including an up-to-date brick factory that produced for federal buildings in the Prairies. Discipline and the organization of staff and inmates was functionally the same as everywhere else in Canada, however: forced labour, the silence system, limited privileges and entertainments, a semi-military staff force, and an isolated location far from major population centres.

The majority of inmates were sentenced from Saskatchewan and Alberta, but throughout the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s, Saskatchewan Penitentiary was used as an overflow facility from overcrowded Eastern prisons. In April 1929, dozens of mostly malcontent prisoners were transferred from Kingston Penitentiary. A “row” was expected with these men, but they were not closely watched or segregated from the main population. In November 1929, there were 430 prisoners at Saskatchewan Penitentiary – almost 60 were from Kingston.

The staff at Saskatchewan Penitentiary were warned on the morning of November 14, 1929, by a ‘stool pigeon’ that all work crews (called gangs) would refuse to leave their places of work “until all their demands were met with.” The stool pigeon had no idea who the ringleaders were or the demands, but the Deputy Warden, Robert Wyllie, ordered his officers to keep “a sharp lookout” for suspicious actions. Over 70 prisoners were working outside the walls in two large groups - building a road and laying sewage pipe - and they were supposed to be the epicentre of the strike. Indeed, the whole day of the 14th staff had observed them talking and passing hand gestures. Other warnings came in throughout the day, so Wyllie ordered the penitentiary locked down and the next day interviewed several inmates at random who confessed they had no idea how word about the strike leaked out. For reasons we’ll get into, they were "amazed at being locked in their cells" and surprised by the swift reaction from the Deputy Warden. During the morning of the 15th, one man named Ford was strapped 24 times for attempting to incite a disturbance in his cell block. Noise and shouting echoed throughout the ranges.

Prisoners working on a building foundation at Saskatchewan Penitentiary, c. 1927

In a state of growing panic, Wyllie first phoned Warden W. J. McLeod, on medical leave since September and so sick he could barely answer the phone. Wyllie then telegraphed Ottawa in a vague way, indicating a “serious situation” and asking for someone to come and take charge. Unsure of what was going on, the Superintendent of Penitentiaries, W. St. Pierre Hughes, dispatched five trusted officers from Manitoba Penitentiary, summoned the nearest RCMP detachment, and ordered his personal hatchet-man, Inspector of Penitentiaries E. R. Jackson, to proceed to Prince Albert and take charge. Jackson would be accompanied by R. M. Allan, Structural Engineer, who had worked at Saskatchewan Penitentiary for a decade in the 1910s and "who knew the prison from long experience."

Almost everything in the historical record about this episode comes from Jackson and Allan’s investigation. Their personalities and prerogatives colour completely the available accounts. They were not great record keepers. They were, like many civil servants of the era, bitchy gossips. Both men were known as severe disciplinarians. Jackson, though only appointed as an Inspector in 1924, had become an indispensable figure to Superintendent Hughes. Jackson would be sent to institutions that Hughes viewed as insufficiently following his regulations, or where inmate unrest posed a problem. Jackson was sent to handle a riot at St. Vincent de Paul Penitentiary in December 1925, ordering a brutal round of lashings against accused agitators. He headed the British Columbia Penitentiary for a year and a half when Hughes fired the warden on spurious ground.

It was at B.C. Pen that Jackson met Allan, then the Chief Industrial Officer, and the two would work together closely not just at Prince Albert but also in the construction and opening of Collin’s Bay Penitentiary in Kingston. Jackson also was acting warden at Kingston Penitentiary in summer 1930. One KP lifer testified in 1932 that Jackson was “a mean son of a bitch” who ordered draconian punishments for relatively minor offences. Allan would himself become warden of Kingston Penitentiary in mid-1934, and held that position until 1954.

In short, these were not men sympathetic to prison officers they viewed as incompetent or remotely curious about inmate complaints. Their investigation was about establishing blame and getting things back to ‘normal.’ They concurred with Hughes that "men never rebel where there is a tight grip retained of them by management." There is some truth to this, as sociologist Bert Useem has repeatedly argued in his work on American prison riots: a ruthless but effective and well organized prison staff is likely to stop even the best organized prisoner protest.

In a strictly hierarchical, patrimonial system like an early 20th century penitentiary, where all authority rests with a few men at the top, failures of leadership are often critical. This is a factor often overlooked in popular and academic histories of prisoner resistance and riots (rightly so, perhaps, as we should focus on the actions of the incarcerated, nor their jailers). Of course, strikes and riots in prisons, as elsewhere, never just happen – as Hughes himself noted, this “must have been developing for sometime - [revolts] never occur in a day or two."

This photo shows the chief officers involved in this event. From left to right: Saskatchewan Penitentiary Deputy Warden R. Wyllie and Warden W. J. Macleod, Superintendent of Penitentiaries W. S. Hughes, Accountant G. Dillon, Inspector of Penitentiaries E. R. Jackson.

Jackson quickly fixed blamed on Deputy Warden Wyllie. They were "very much surprised by the lack of initiative" of Wyllie, who seemed to have been cowed by the fifty men working on the outside that had tried to strike. This despite the presence of almost a dozen armed officers nearby! Wyllie had had a nervous breakdown from stress, and had allowed, in Jackson’s eyes, a “lack of efficiency and discipline” to pervade the prison. He was "indecisive" in giving punishments at Warden’s Court, causing “the inmates to gloat over and ridicule the officers…" Inmates charged with fighting, insolence, or swearing at officers were warned or reprimanded, the least severe punishment for such severe infractions of the rules. Several officers felt that “there was no use of reporting the inmates” and so they "closed their eyes to a lot of infractions." Another officer thought that since September 1929 "inmates had became cocky … would laugh in the my face and...tell me to report him when he liked...for it would do no good." This situation was very similar to Kingston Penitentiary before the riot in October 1932, and, indeed, typified the crisis of the 1970s in federal prisons as well.

The November 14-15 disturbance was actually not the first strike episode at Saskatchewan Penitentiary that year. There had been unrest or talk of strikes among the prisoners since early September, with a general atmosphere of defiance and mockery of authorities. Many inmates resisted by going “through the motion of working" but not actually completing tasks. There had been a work refusal in late September, and two other strikes or work refusals in the middle of October. In these cases Wyllie intervened personally, but did not investigate, punish the strikers, or rectify the situation. There are not even reports on file about these events, and the record of reports against inmates for violating rules bears out this feeling that prisoners would “have their own way” and no ‘effective’ action would be taken against their rebellions. That is, effective by the standards of guards, who expected their commands to be obeyed absolutely.

Few demands were discovered – or least Jackson did not think the ones he turned up were worth elaborating on. There seemed to have been general opposition to the Steward's department – the “grub” was satisfactory, but apparently not distributed fairly, according to the inmates. The Steward and Deputy Warden had allowed inmates to place “special instructions” for their meals, and they would shout out their orders like they were at a diner, or exchanged their tickets to swap meals. The queued, single file, food line, with no talking and the same meal for everyone, had disappeared, and restoring this system was Jackson’s first act when he took over. Of course, food in prisoner protests stands in for more than just a meal, while also representing a very basic need that is one of the few things to look forward to during days of monotonous labour.

Much of the unrest centred on certain work crews, whose officers were resented, and communication with family, better work arrangements, socializing, access to newspapers, all are mentioned in passing in the investigation files. The “Kingston boys” were also the loudest supporters or organizers of the strikes, and they apparently resented being exiled to Saskatchewan. At least one inmate, Radke, told other inmates he wanted the strike to force a Royal Commission to investigate the prison. This kind of demand would be repeated again and again in 1932 and 1933 during prison riots across Canada.

Cell block in 1930 at Saskatchewan Penitentiary. The beds in the corridors are due to severe overcrowding.

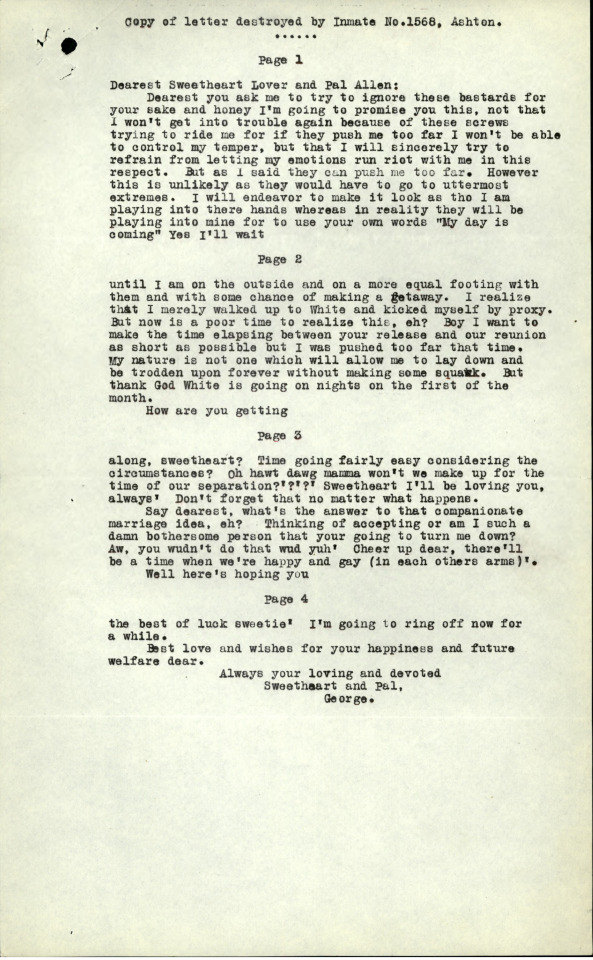

George Ashton was singled out as one of the organizers of the abortive strike. Serving a term for armed robbery, he was one of the Kingston transfers. On November 15, 1929, he was caught trying to throw a letter away. This letter is addressed to another inmate who he had hoped to escape with. Ashton, "a troublesome, Smart Alec kid,” was sentenced to be shackled for ten days to his cell bars and to spend sixty days in isolation. Typical of Jackson’s more ‘effective’ regime.

Ashton’s note was addressed to his 'Pal', Allen, alias Bertram Allen Jones. Both worked in different work crews labouring outside the walls. Ashton’s letter to Jones identifies him as his sweetheart and lover, and promised that "he'll not get into trouble again because of these screws...I will sincerely try to refrain from letting my emotions run riot....My nature is not one which will allow me to lay down and be trodden upon forever without making some squawk." Ashton indicated he wanted to "make the time elapsing between your release and our reunion as sort as possible." He asked how Jones’ time was going, and ended by expressing his longing and desire to be with Jones:

"OH hawt dawg mamma won't we make up for the time of our separation??? Sweetheart I'll be loving you..." Say what's the answer to that companionate [sic] marriage idea? Thinking of accepting or am I such a damn bothersome person that your going to turn me down?.....there'll be a time when we're happy and gay (in each other arms).”

This was apparently one of many letters the two had exchanged, and contrary to the usual arrangements of wolves and punks in early 20th century prisons, where older men ‘protect’ younger inmates, often to extract sexual favours, this was apparently a consensual and sincere relationship. Not as uncommon as might be expected, of course, but it’s unusual to find such boldly expressed desire and love in this period of the archival record. Of course, Hughes thought this letter confirmed that Ashton was "a low bestial sort." Jones was identified as one of the other ringleaders, and he and Ashton had been seen talking to each other and making hand gestures several times in the months leading up to their strike attempt.

Who these men were and what happened to them after their time in prison I don’t know, yet.

Transcript of Ashton's letter to Jones, the only part of their correspondence that survives today

Inspector Jackson stayed in charge for another two months at Saskatchewan Penitentiary. An attempt to start on insurrection on November 20, 1929, was broken by strapping four of the leaders: “since then the Prison is absolutely quiet." Always full of himself, Jackson included letters of thanks from officers who praised his leadership, including the prison doctor: "We were drifting badly, discipline had practically ceased...now we are back and a Prison once more." He felt satisfied that retiring Wyllie and Warden Macleod had solved the problem, and left Allan in charge starting in mid-December 1929.

While I have no doubt that Deputy Warden Wyllie was responsible for the growth of an inmate strike movement, I don’t believe it is purely a case of his incompetence allowing inmates to organize. Rather, he proved himself to be an open door to prisoners already planning protests, and his inability to act with the severity expected by prisoners and staff alike encouraged further protests. Like a lot of federal civil servants, Wyllie was likely promoted above his abilities, with his loyalty to Hughes, seniority, indispensability to superior officers, and local influence helping to further his career. This was Jackson’s trajectory as well, ironically – once Hughes retired in early 1932, Jackson was on the outs, transferred to clerical duties in Ottawa, and he was dismissed in December 1932 as part of the purge initiated of penitentiary officers by the new Superintendent.

Additionally, it is clear to me that the issues at Saskatchewan Penitentiary extended beyond one officer – and indeed blaming Wyllie absolved a bunch of other officers of corruption and incompetence. Serious issues in the Hospital, Kitchen, School, and Workshops, were identified by Allan when he took over, with trafficking and contraband in cigarette papers, pipes, lighters, smuggled cigarettes, photographs and letters widespread. The Boiler House, where “considerable contraband has been located,” had seven inmate workers, who laboured "without direct supervision...” These men resented the crackdown and refused to work in February 1930 – which revealed to Allan the danger of allowing inmates to have full control of the power plant of the penitentiary.

Allan fired the officer in charge of the boiler house, the hospital overseer, the storekeeper, and reprimanded other officers for failing to confiscate contraband items. Fake keys were found throughout the prison, likely to be used in escapes or smuggling. Inmates had been allowed for years to order magazines direct from the publisher – and did not have them passed through the censor. Another mass strike was attempted in January 1930, apparently to protest Allan cracking down on these deviations from the regulations. As always, it should be recalled that what the officers saw as corruption or smuggling against regulations were all activities that made 'doing time' easier.

Why care about this episode, beyond some of the points I’ve already raised? One aspect of historical study I am most interested in are the precursors to a major event - the struggles, organizing, movements, victories and defeats that (sometimes with hindsight, sometimes without) shape a more influential and decisive event. This is especially difficult when writing the history of prisoner resistance, which often appears a discontinuous history, full of gaps and seemingly sudden flare-ups. The 1930s were a decade of prison riots, strikes, escapes and protests in federal and provincial prisons, but obviously these did not arise from nothing. The 1929 strike attempt at Saskatchewan Penitentiary is a transitional event – similar to earlier strikes and protests going back to the late 19th century, but occurring at the very start of the Great Depression, a premonition of things to come.

#prince albert penitentiary#prince albert#prison strike#prison riot#convict revolt#prisoner organzing#prison administration#prison management#causes of prison riots#my writing#dominion penitentiaries#saskatchewan history#queer history#history of homosexuality in canada#great depression in canada#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada

30 notes

·

View notes