#anthropology of odor

Text

COVID-19, Anosmia, and the Importance of Smell

Hannah Gould and Gwyn McClelland, editors of Aromas of Asia, discuss anosmia as it relates to the COVID-19 pandemic, the tricky nature of olfaction, and where the phenomenon of smell as transnational exchange began.

Of the many serious, and still emerging, impacts of infection with COVID-19, anosmia, or a loss of the sense of smell, is less often discussed. Yet the condition is said to affect almost half of all diagnosed patients, and although most people regain olfaction within a month, for some, anosmia lingers, transforming how they eat, drink, and interact with the world. People may also experience a condition of paranosmia, or phantom, and often unpleasant, smells.

In the introduction to our new interdisciplinary edited collection, Aromas of Asia: Exchanges, Histories, Threats, we discuss how this phenomenon speaks to the tricky nature of olfaction: its profound impact in shaping one’s everyday experience of the world and the popular dismissal of its significance. For, perhaps it is only in losing a sense that we are troubled and thus realise its significance. Anosmia is a condition that demonstrates how smell (or its lack) moves between bodies and traverses scales, as an intimate, personal experience of the world created by the transnational movement of pathogens within a global pandemic.

Smell is thus a particularly generative phenomenon to draw upon when theorizing the dynamics of transnational exchange. And this particular transnational exchange of the pandemic, of course, began in Asia.

Western cultural hierarchies and intellectual traditions have tended to elevate the importance of vision, or hearing, while marginalizing senses including smell, taste, or touch. With a few notable exceptions, contemporary scholarship still remains strongly wedded to English-language or Western scholarly concerns and contexts.

Our new collection of essays relocates the discussion of olfaction to the Asian region, considering how the mobility of olfaction makes social worlds, identifies prejudices or threats, and implements power games of scent and odor. Wherever smell is interpreted as threat, and has potential to be used to violently enforce differences in ethnicity, gender, caste, and class, questions of smell can have serious implications.

We were concerned in this work to critique sensory colonialist tropes that align Asia and its peoples with more “debased” senses, thus resisting a dichotomy of “West-vision-logic” and “Asia-smell-emotion.” Where associated with smell, Asian peoples and cultures have been historically cast in two extremes: on the one hand heavily perfumed or “stinky,” and on the other overly sanitized, odorless or antiseptic. While examining and critiquing these sensory stereotypes, our collection engages with Asia as a heterogeneous and changing complex of scentscapes that have blended together and come apart throughout history. The boundaries of this region are not presumed to exist before olfaction but rather emerge through histories of sensory exchange.

Our contributors consider periods from antiquity to the present and examine various transnational contexts across East, Southeast, and South Asian regions. We do not claim the spread as representative or exhaustive, but the chapters provide a robust cross section of the “scentscapes” that traverse the region. Thus, incisive essays and careful research was essential to achieve the methodological richness and conversation between disciplines evidenced in this book. Besides the editors, the authors, in order of their contributions, are Lorenzo Marunucci, Peter Romaskiewicz, Qian Jia, Gaik Cheng Khoo, Jean Duruz, Gwyn McClelland, Shivani Kapoor, Aubrey Tang, Saki Tanada, Adam Liebman, and Ruth E. Toulson. The disciplines brought together in this volume include anthropology, history, film studies, fine arts, food studies, literature, philosophy, political studies, and religious studies.

Strong-smelling miasmas, or drifting clouds of noxious air, have been central to human understandings of disease transmission. Well after the emergence of germ theory, fear of smells in the form of miasma continues to this day. Some commentators used olfactory evidence in positioning Chinese “wet markets” as the site of origin for COVID-19 virus. For example, in one paper in The COVID-19 Reader (2021), the writer suggests that “a lack of hygiene [at wet markets] was obvious from the smells and scattered wastes.” From this olfactory experience, the authors describe their lack of surprise that a pandemic might emerge from this place. We compare this in our introduction to another study of 2020 that shows how freshness is constructed and valued in sensory experiences of markets within China. Perceiving smells or odors as threats can reinforce, especially during the pandemic, the alterity of Asia as the other to the West. COVID-19 illustrated how olfaction is an intimately embodied, individual experience, but also a social phenomenon traveling between bodies and communities—and around the globe. In our collection, Aromas of Asia, we focus on the interconnections of sensory worlds, but we do so by offering a transnational and located approach to scentscapes in Asia, even as they are founded on mobility and exchange.

Aromas of Asia: Exchanges, Histories, Threats is now available from Penn State University Press. Learn more and order the book here: https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-09541-7.html. Save 30% w/ discount code NR23.

#COVID-19#COVID 19#COVID19#Pandemic#Smell#Anosmia#Miasma#Olfactory#Scent#Asia#China#PSU Press#Penn State University Press#Penn State

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

[A. XVIII Century - cont'd]

[2. Second obstacle to anthropology: Sensation - cont'd]

b. Finally, their concrete contents [similar but in contrast to Husserl's notion of hyle] are

i. not so much allusion to

a truth of nature

an index of a transcendence

or undertow of a teleology

ii. but only way of being originary [i.e., not derived] absolutely morning of the subject [i.e., a choice of origin that places the undeniability of sensation in the role of unmediated, directly constituted evidence]. Example which is:

“smell of rose, carnation, jasmine, violet [...]. In a word, odors are in this respect only one's own modifications or ways of being; and it cannot believe itself to be anything else [...]” (Traité des sensations).

a sensation that comes unmediated, and from the outset, in first person

– Michel Foucault, Knowledge of Man and Transcendental Reflection (Critical Thought and Anthropology), d'apres La Question Anthropologique, Cours 1954-1955, edited by Ariana Sforzini

0 notes

Text

Woman burned alive on Texas roadside in ritzy neighborhood: police

Woman Found Burned Alive in Tragic Incident

Austin, Texas - Last month, firefighters were confronted with a horrifying scene when they discovered a woman engulfed in flames on the side of a road in an upscale Austin suburb. The victim, identified as Melissa Davis, left her family in a state of profound grief as they struggle to come to terms with this incomprehensible loss.

Melissa Davis, 33, was found near the intersection of Mesa Drive and Cat Mountain Drive on the morning of September 29. Firefighters were responding to a 911 call about a grassfire when they made this grim discovery.

"It's an incredible loss for all of us," expressed Davis's stepmother, Mary Anne Castles. She further stated that it wasn't her place to provide additional comments on behalf of the family.

Mysterious Circumstances

The authorities have not yet identified a suspect in this perplexing case. Melissa Davis, an enthusiastic traveler and a master's degree holder from the University of North Texas, was found with her body ablaze in a 10-foot area adjacent to a home's fence and the roadside in Northwest Hills.

A search warrant obtained by KXAN revealed the presence of a lighter near the scene, along with a strong odor of accelerant surrounding the charred body. A police K-9 also uncovered a butcher knife in an area emitting a potent smell of gasoline or diesel. Investigators believe this knife was discarded in the fire in an attempt to destroy evidence.

Autopsy Reveals Grim Details

An autopsy disclosed the chilling fact that Melissa Davis was still alive when she was set on fire, as reported by KXAN. The authorities are currently seeking access to her cellphone records through the search warrant, as her phone, presumed to be with her prior to the incident, remains missing.

Her family members reported that they last saw her the day before her tragic murder when she mentioned she was going to an Apple store to fix her phone.

Missing Vehicle and Plea for Information

Compounding the mystery, Melissa Davis's 2016 blue Toyota 4Runner, bearing the license plate KYV3765, is also missing. The Austin Police Department has released a photo of the vehicle and is appealing to the public for assistance in locating it. If you have any information, please contact APD at 512-974-TIPS.

Remembering Melissa Davis

Melissa Davis hailed from Fort Knox, Kentucky, and came from a military family. Her academic achievements include a bachelor's degree in anthropology and a master's in international sustainable tourism from the University of North Texas. She was also a loving "dog mom" to her cherished companion, Dudley, with whom she enjoyed the great outdoors, including long hikes and camping trips.

This tragedy has left her family and community in shock, with many seeking answers to this unfathomable crime.

Read the full article

0 notes

Link

Check out this listing I just added to my Poshmark closet: Anthropologie- 11.1.TYLHO- Plaid Button Down Tee/ Dress- Small- EUC.

0 notes

Text

By: John McWhorter

Published: Nov 19, 2021

Our times often put me in mind of Tennessee Williams’s “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” when Big Daddy says: “What is the smell in this room? Don’t you notice it, Brick? Don’t you notice a powerful and obnoxious odor of mendacity in this room?”

These days, an aroma of delusion lingers, with ideas presented to us from a supposedly brave new world that is, in reality, patently nonsensical. Yet we are expected to pretend otherwise. To point out the nakedness of the emperor is the height of impropriety, and I suspect that the sheer degree to which we are asked to engage in this dissimulation will go down as a hallmark of the era: Do you believe that a commitment to diversity should be crucial to the evaluation of a candidate for a physics professorship? Do you believe that it’s mission-critical for doctors to describe people in particular danger of contracting certain diseases not as “vulnerable (or disadvantaged)” but as “oppressed (or made vulnerable or disenfranchised)”? Do you believe that being “diverse” does not make an applicant to a selective college or university more likely to be admitted?

In some circles these days, you are supposed to say you do.

The San Diego State University physics department is seeking a physicist. The job description asks candidates to show how they “satisfy” at least three of the following criteria: “(a) are committed to engaging in service with underrepresented populations within the discipline, (b) have demonstrated knowledge of barriers for underrepresented students and faculty within the discipline, (c) have experience or have demonstrated commitment to teaching and mentoring underrepresented students, (d) have experience or have demonstrated commitment to integrating understanding of underrepresented populations and communities into research, (e) have experience in or have demonstrated commitment to extending knowledge of opportunities and challenges in achieving artistic/scholarly success to members of an underrepresented group, (f) have experience in or have demonstrated commitment to research that engages underrepresented communities, (g) have expertise or demonstrated commitment to developing expertise in cross-cultural communication and collaboration, and/or (h) have research interests that contribute to diversity and equal opportunity in higher education.”

They’re all admirable activities and aims. However, they are vastly less applicable to becoming or being a physicist than to, say, social work, education or even disciplines such as anthropology and sociology. That an applicant to the university’s physics department would be required to meet such benchmarks is a very modern proposition, and probably leaves most people now reading this job posting — physicists or not — scratching or shaking their heads. Yet this emphasis is increasingly found in fields related to the hard sciences: Earlier this year, for instance, leaders of the National Institutes of Health announced their “UNITE initiative,” a “framework to end structural racism across the biomedical research enterprise.”

The notion seems to be that practitioners and scholars, across disciplines, must devote a considerable part of their time to putatively antiracist initiatives. It’s a bold proposition, but given how shaky its actual justification is, it is reasonable to think that lately this devotion is being imposed by fiat, as opposed to being an organic outpouring. And if the price for questioning that notion is to be seen as sitting somewhere on a spectrum ranging from retrogressive to racist, it’s a price few are willing to pay. One is, rather, to pretend.

The American Medical Association and the Association of American Medical Colleges have released a “guide” that urges practitioners to employ a left-leaning glossary in pursuit of “health equity.” The problem is that what they recommend would be all but inapplicable in the real world.

While caring for their patients, doctors are encouraged to mold their statements to reflect that vulnerability isn’t merely extant, but something imposed upon some patients. That is true in a technical sense, but how realistic — or useful relative to the care itself — is it to propose that physicians should say “oppressed” rather than “vulnerable”? Or, based on the same sociopolitical perspective, what is the utility of replacing the statement, “Low-income people have the highest level of coronary artery disease in the United States” with “equity-focused language that acknowledges root causes” like “People underpaid and forced into poverty as a result of banking policies, real estate developers gentrifying neighborhoods, and corporations weakening the power of labor movements, among others, have the highest level of coronary artery disease in the United States”? Surely, even in our age, clinicians should focus on treatment, not medical newspeak.

The chances that real doctors will ever use language like this are minuscule. Commitment to healing the sick makes it plain that energy should be focused on ways of attending to the unhealthy, rather than to studiously ideological ways of talking about and to them. This means that all polite engagement with documents like this, from the very production of them to any forums in which their propositions are engaged politely, amounts to an act.

The jukebox musical based on Alanis Morissette’s “Jagged Little Pill” includes a character who’s a white mother of a Black daughter. In one scene, friends mention that the daughter will be more likely to get into a top-level university because she’s Black. The mother takes this as a slam and gives a sharp retort implying that the very assumption is racist, with the additional assumption that the audience will agree (which it vocally did the night I attended a performance).

This, though, is fake. That selective schools regularly admit Black students with adjusted standards is undeniable. Examples include “Harvard’s race-conscious admissions program” — as U.S. Circuit Judge Sandra Lynch described it last year — and the circumstances of the well-known Gratz v. Bollinger Supreme Court decision, where this aspect of the admissions process was widely aired, as among a number of other cases over the past few decades.

My point here isn’t to debate the pros and cons of affirmative action. There are legitimate arguments on both sides of that debate. My point is that the existence of various forms of affirmative action in admissions is a fact, and saying otherwise is fiction. Beyond this musical, it is often suggested that it is disingenuous, if not racist, to surmise that a Black student was admitted to a school via racial preferences. But this leaves the question as to just what we are to assume the aim of these policies has been, when the educational establishment so vociferously defends them.

That athletes and legacy students are also admitted via preference does not belie the fact that there are also, at many schools, admissions preferences based on race. That this is not to be mentioned is a kind of politesse requiring that we prevaricate about a subject already difficult enough to discuss and adjudicate.

All of this typifies a strand running through our times, a thicker one than always, where we think of it as ordinary to not give voice to our questions about things that clearly merit them, terrified by the response that objectors often receive. History teaches us that this is never a good thing.

John McWhorter (@JohnHMcWhorter) is an associate professor of linguistics at Columbia University. He hosts the podcast “Lexicon Valley” and is the author, most recently, of “Woke Racism: How a New Religion Has Betrayed Black America.”

==

We guiltlessly reject obligation to participate in the fictions and rituals of the traditionally religious. We know their grace at dinner and their magic spells during a wedding do nothing, and we don't feel obliged to affirm otherwise.

Why then, are we obligated to participate in the fictions and sacraments of The Elect? We know many of the their platitudes and canards aren't true, and yet we feel obligated to affirm otherwise.

What's actually true actually matters.

#John McWhorter#The Elect#neoracism#antiracism as religion#antiracism#wokeness as religion#wokeism#woke activism#cult of woke#woke#religion is a mental illness

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

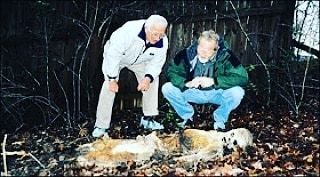

Decomposition of Body:

According to Dr. Arpad A. Vass, a Senior Staff Scientist at Oak Ridge National Laboratory and Adjunct Associate Professor at the University of Tennessee in Forensic Anthropology, human decomposition begins around four minutes after a person dies and follows four stages: autolysis, bloat, active decay, and skeletonization.

Stage One: Autolysis

The first stage of human decomposition is called autolysis, or self-digestion, and begins immediately after death. As soon as blood circulation and respiration stop, the body has no way of getting oxygen or removing wastes. Excess carbon dioxide causes an acidic environment, causing membranes in cells to rupture. The membranes release enzymes that begin eating the cells from the inside out.

Rigor mortis causes muscle stiffening. Small blisters filled with nutrient-rich fluid begin appearing on internal organs and the skin’s surface. The body will appear to have a sheen due to ruptured blisters, and the skin’s top layer will begin to loosen.

Stage Two: Bloat

Leaked enzymes from the first stage begin producing many gases. The sulfur-containing compounds that the bacteria release also cause skin discoloration. Due to the gases, the human body can double in size. In addition, insect activity can be present.

The microorganisms and bacteria produce extremely unpleasant odors called putrefaction. These odors often alert others that a person has died, and can linger long after a body has been removed.

Stage Three: Active Decay

Fluids released through orifices indicate the beginning of active decay. Organs, muscles, and skin become liquefied. When all of the body’s soft tissue decomposes, hair, bones, cartilage, and other byproducts of decay remain. The cadaver loses the most mass during this stage.

Stage Four: Skeletonization

Because the skeleton has a decomposition rate based on the loss of organic (collagen) and inorganic components, there is no set timeframe when skeletonization occurs.

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

Early in the formidable new essay collection “Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning,” the poet Cathy Park Hong delivers a fatalistic state-of-the-race survey. “In the popular imagination,” she writes, “Asian Americans inhabit a vague purgatorial status . . . distrusted by African Americans, ignored by whites, unless we’re being used by whites to keep the black man down.” Asians, she observes, are perceived to be emotionless functionaries, and yet she is always “frantically paddling my feet underwater, always overcompensating to hide my devouring feelings of inadequacy.” Not enough has been said, Hong thinks, about the self-hatred that Asian-Americans experience. It becomes “a comfort,” she writes, “to peck yourself to death. You don’t like how you look, how you sound. You think your Asian features are undefined, like God started pinching out your features and then abandoned you. You hate that there are so many Asians in the room. Who let in all the Asians? you rant in your head.”

Hong, who teaches at Rutgers, is the author of three poetry collections, including “Dance Dance Revolution,” which was published in 2007, and is set in a surreal fictional waystation called the Desert, where the inhabitants speak a constantly evolving creole. (“Me fadder sees dis y decide to learn Engrish righteo dere,” the narrator says.) “Minor Feelings” consists of seven essays; Hong explains the book’s title in an essay called “Stand Up” that centers on Richard Pryor’s “Live in Concert.” Minor feelings are “the racialized range of emotions that are negative, dysphoric, and therefore untelegenic.” One such minor feeling: the deadening sensation of seeing an Asian face on a movie screen and bracing for the ching-chong joke. Another: eating lunch with white schoolmates and perceiving the social tableaux as a frieze in which “everyone else was a relief, while I felt recessed, the declivity that gave everyone else shape.” Minor feelings involve a sense of lack, the knowledge that this lack is a social construction, and resentment of those who constructed it.

In “The End of White Innocence,” Hong describes her childhood home as “tense and petless, with sharp witchy stenches.” Her father drank; her mother, she writes, “beat my sister and me with a fury intended for my father.” Her parents grew up in postwar poverty in Korea—as a child, her father caught sparrows to eat. In order to get a visa to immigrate to the United States, he pretended to be a mechanic, and ended up working for Ryder trucks in Pennsylvania, where he was injured, and fired. He moved to Los Angeles and found a job selling life insurance in Koreatown, then bought a dry-cleaning supply warehouse, and became successful enough to send Hong to private high school and college. He recognized that Americans valued emotional forthrightness in business and developed a particular way of speaking at work. “Thanks for getting those orders in,” Hong remembers him saying on the phone. “Oh, and Kirby, I love you.”

Hong feels ashamed, but not of her proximity to awkward English, or her features, or witchy domestic stenches. “My shame is not cultural but political,” she writes. She is ashamed of the conflicted position of Asian-Americans in the racial and capital hierarchy—the way that subjugation mingles with promise. “If the indebted Asian immigrant thinks they owe their life to America, the child thinks they owe their livelihood to their parents for their suffering,” Hong writes. “The indebted Asian American is therefore the ideal neoliberal subject.” She becomes a “dog cone of shame,” a “urinal cake of shame.” Hong’s metaphors are crafted with stinging care. To be Asian-American, she suggests, is to be tasked with making an injury inaccessible to the body that has been injured. It is to be pissed on at regular intervals while dutifully minimizing the odor of piss.

For a long time, Hong recounts in the book’s first essay, she did not want to write about her Asian identity. By the time she began studying for her M.F.A., at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, she had concluded that doing so was “juvenile”—and she couldn’t find the right form, anyway. The confessional lyric felt too operatic, and realist fiction wasn’t right, either: “I didn’t care to injection-mold my thoughts into an anthropological experience where the reader, after reading my novel, would think, The life of Koreans is so heartbreaking!” In “Stand Up,” she asks, “Will there be a future where I, on the page, am simply I, on the page, and not I, proxy for a whole ethnicity, imploring you to believe we are human beings who feel pain?” The predicament of the Asian-American writer, as Hong articulates it, is to fear that both your existence and your interpretation of that existence will always be read the wrong way. At Iowa, Hong noticed other writers of color stripping out markers of race from their poems and stories to avoid being “branded as identitarians.” It was only later that Hong realized that all of the writers she had noticed doing this were Asian-American.

I read “Minor Feelings” in a fugue of enveloping recognition and distancing flinch. I have tended to interpret my own acquiescence to and resentment of capitalism in generational terms rather than racial ones; many people my age seem to accept economic structures that we find humiliating because we reached adulthood when the margins of resistance appeared to be shrinking. I know, too, that my desire to attain financial stability is connected with a hope, bordering on practical obligation, to protect my parents, as they grow older, from the worst of the country that they immigrated to for my benefit. But, for some reason, I haven’t written very much about that. Was I, like Hong’s grad-school classmates, afraid of being branded as an identitarian? Had I considered the possibility of being positioned as a proxy for an entire ethnic group, and, unlike Hong, turned away?The term “Asian-American” was invented by student activists in California, in the late sixties, who were inspired by the civil-rights movement and dreamed of activating a coalition of people from immigrant backgrounds who might organize against structural inequality. This is not what happened; for years, Asian-Americans were predominantly conservative, though that began changing, gradually, during the Obama years, then sharply under Trump. Today, “Asian-American” mainly signifies people with East Asian ancestry: most Americans, Hong writes, think “Chinese is synecdoche for Asians the way Kleenex is for tissues.” The term, for many people—and for Hollywood—seems to conjure upper-middle-class images: doctors, bankers. (We are imagined as the human equivalent of stainless-steel countertops: serviceable and interchangeable and blandly high-end.) But, although rich Asians earn more money than any other group of people in America, income inequality is also more extreme among Asians than it is within any other racial category. In New York, Asians are the poorest immigrant group.Hong describes a visit to a nail salon, where a surly Vietnamese teen-age boy gives her a painful pedicure. She imagines him and herself as “two negative ions repelling each other,” united and then divided by their discomfort in their own particular Asian positions. Then she pauses. “What evidence do I have that he hated himself?” she wonders. “I wished I had the confidence to bludgeon the public with we like a thousand trumpets against them,” she writes elsewhere. “But I feared the weight of my experiences—as East Asian, professional class, cis female, atheist, contrarian—tipped the scales of a racial group that remains so nonspecific that I wondered if there was any shared language between us. And so, like a snail’s antenna that’s been touched, I retracted the first person plural.” Hong doesn’t fully retract it—“we” appears fairly often in the book—but she favors the second person, deploying a “you” that really means “I,” in the hope that her experience might carry shards of the Asian-American universal.

Throughout the book, Hong at once presumes and doesn’t presume to speak for people whose families come from India, say, or Sri Lanka, or Thailand, or Laos—or the Philippines, where my parents were born. The Philippines were under Spanish control from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, and under American control until the middle of the twentieth. Many Filipinos have Spanish last names and come to the States speaking English; many have dark skin. In his book “The Latinos of Asia,” the sociologist Anthony Christian Ocampo argues that Filipinos tend to manifest a sort of ethnic flexibility, feeling more at home, compared with members of other Asian ethnic groups, with whites, African-Americans, Latinos, and other Asians. The experience of translating for one’s parents is often framed as definitive for Asian-Americans, but it’s not one that many Filipinos of my generation share; my parents came to North America listening to James Taylor and the Allman Brothers, speaking Tagalog only when they didn’t want their kids to listen. I grew up in a mixed extended family, with uncles who are black and Mexican and Chinese and white. Ocampo cites a study which found that less than half of Filipino-Americans checked “Asian” on forms that asked for racial background—a significant portion of them checked “Pacific Islander,” for no real reason. It denoted proximity to Asian-Americanness, perhaps, without indicating a direct claim to it. (About a month ago, at a doctor’s appointment, an East Asian nurse checked “Pacific Islander” when filling out a form for me.)

“Koreans are self-hating,” one of Hong’s Filipino friends tell her. “Filipinos, not so much.” My experience of racism has been different than Hong’s, as has my response to it. Much of the discourse around Asian-American identity centers on racist images associated with the stereotypical East Asian face: single-lidded eyes, yellow-toned skin, a supposed air of placid impassivity. I don’t have that face, exactly, and I’m not sure that I’ve confronted quite the same assumptions; when I hear people perform gross imitations of “Chinese” accents, I don’t know if it hurts the way it does because I’m an Asian person or because I come from a family of immigrants or simply because racism is embarrassing and foul.

If you escape the dominant experience of Asian-American marginalization, have you necessarily done so by way of avoidance, or denial, or conformity? What can you do when colonization is embedded in your family’s history, in your genetic background, in your very face? If I feel comforted in a room full of Asian people rather than alarmed at the possibility that my inner racial anxieties have been cloned all around me, is this another effect of the psychic freedom I’ve been granted with double eyelids and an ambiguously Western last name, or does it mark progress in the form of a meaningful generational shift? In the decade that separates me from Hong, the currency of whiteness has lost some of its inflated cultural value; one now sees Asian artists and chefs and skateboarders and dirtbags and novelists on the Internet, in the newspaper, and on TV. Is this freedom, or is it the latest form of assimilation? For Asian-Americans, can the two ever be fully distinct?

“Minor Feelings” bled a dormant discomfort out of me with surgical precision. Hong is deeply wary of living and writing to earn the favor of white institutions; like many of us, she has been raised and educated to earn white approval, and the book is an attempt to both acknowledge and excise such tendencies in real time. “Even to declare that I’m writing for myself would still mean I’m writing to a part of me that wants to please white people,” she explains. She’s circling the edges of a trap that often appears in Asian-American consciousness, in which love is suspicious and being unloved is even worse. The editors of “Aiiieeeee!,” one of the first anthologies of Asian-American literature—it was published in 1974—argued that “euphemized white racist love” had combined with legislative racism to mire the Asian-American psyche in a swamp of “self-contempt, self-rejection, and disintegration.” A quarter century later, in her book “The Melancholy of Race,” the literary theorist Anne Anlin Cheng described “the double bind that fetters the racially and ethnically denigrated subject: How is one to love oneself and the other when the very movement toward love is conditioned by the anticipation of denial and failure?” In the introduction to his essay collection “The Souls of Yellow Folk,” published in 2018, Wesley Yang writes about a realization that he regards as “unspeakable precisely because it need never be spoken: that as the bearer of an Asian face in America, you paid some incremental penalty, never absolute, but always omnipresent, that meant that you were default unlovable and unloved.”

The question of lovability, and desirability, is freighted for Asian men and Asian women in very different ways—and “Minor Feelings” serves as a case study in how a feminist point of view can both deepen an inquiry and widen its resonances to something like universality. Essays and articles about Asian-American consciousness often invoke issues of dominance and submission, and they often frame these issues according to the experiences of disenfranchised men. The editors of “Aiiieeeee!” call the stereotypical Asian-American “contemptible because he is womanly”; Yang often identifies the Asian-American condition with male rejection and disaffection. Hong reframes the quandary of negotiating dominance and submission—of desiring dominance, of hating the terms of that dominance, of submitting in the hopes of achieving some facsimile of dominance anyway—as a capitalist dilemma. I found myself thinking about how the interest and favor of white people, white men in particular, both professionally and personally, have insulated me from the feeling of being sidelined by America while compromising my instincts at a level I can barely access. Hong writes, “My ego is in free fall while my superego is boundless, railing that my existence is not enough, never enough, so I become compulsive in my efforts to do better, be better, blindly following this country’s gospel of self-interest, proving my individual worth by expanding my net worth, until I vanish.”

I hate my Asian self the way I worry about being written off as a woman writer—which is to say, not at all. Hong concedes that the self-hating Asian may be “on its way out” with her generation: for me, the formulation still has weight, but does not capture the efflorescence of the present. The question, then, is whether the movement toward love, as Anne Anlin Cheng put it, can be made outside the grasp of coercion. Is there a future of Asian-American identity that’s fundamentally expansive—that can encompass the divergent economic and cultural experiences of Asians in the United States, and form a bridge to the experiences of other marginalized groups?The answer depends on whom Asian-Americans choose to feel affinity and loyalty toward—whether we direct our sympathies to those with more power than us or less, not just outside our jerry-rigged ethnic coalition but within it. The history of Asian-Americans has involved repression and assimilation; it has also, to a degree that is often forgotten, involved radicalism and invention. “Aiiieeeee!” was published by Howard University Press, partly as a result of the friendship that one of its editors, Frank Chin, formed with the radical black writer Ishmael Reed. Gidra, an Asian-American zine that was published in Los Angeles in the nineteen-sixties and seventies, called for the “birth of a new Asian—one who will recognize and deal with injustices.” (Gidra reported on cases of local discrimination and profiled activists such as Yuri Kochiyama; it’s now back in print.) To occupy a conflicted position is also to inhabit a continual opportunity—the chance, to borrow Hong’s words, to “do better, be better,” but in moral and political rather than economic terms.In one of the essays in “Minor Feelings,” called “An Education,” Hong looks back on her friendships in college with two other Asian-American girls—brash, unstable hellions named Erin and Helen. They made art together, they traded poetry, they got drunk and fought and made up. “We had the confidence of white men,” Hong recalls, “which was swiftly cut down after graduation, upon our separation, when each of us had to prove ourselves again and again, because we were, at every stage of our career, underestimated.” The story of their friendship is a story about the way that loving others is often a less complex and more worthy act than loving ourselves—and the way that love can blunt the psychological force of marginalization. If structural oppression is the denial of justice, and if justice is what love looks like in public, then love demonstrated in private sometimes provides what the world doesn’t. Hong is writing in agonized pursuit of a liberation that doesn’t look white—a new sound, a new affect, a new consciousness—and the result feels like what she was waiting for. Her book is a reminder that we can be, and maybe have to be, what others are waiting for, too.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Indian Burial Grounds

The origins of the “Indian burial ground” legend come from sightings of Native American ghosts near areas rumored, or even proven, to be the final resting place of a local tribe. Such areas can be an old farmhouse in a Midwestern town or even a multimillion-dollar mansion in the Hollywood Hills.

In fact, the remains of the dead were blamed for the vacancy of the Hollywood mansion on Solar Drive, and a murder was rumored to have occurred there. It was deemed uninhabitable after squatters, drug dealers, and thrill-seeking teenagers ravaged the place. But, in the case of the house, the existence of Native American graves was unproven, and it becomes a perfect example of the power and potency of the lore.

Strange occurrences are attributed to burial grounds automatically, without even needing to research the history of the area. It doesn’t take a master’s degree in anthropology to see that this stems from our fascination with a mystical and highly spiritual culture and religion perceived of the American Indian. Instead of the body resting and the soul rising, the soul lingers, especially when disturbed.

So, why does this legend still capture our imagination and frighten us today? Even a skeptic can be spooked by visiting one of the many burial grounds in the United States at dark. Thousands are drawn, for example, to a suburb in Long Island, New York to see the actual house featured in the movie The Amityville Horror. The house, purported to be built over Native American remains, was the place of the horrific murder of six people. Even after the murders, strange noises and footsteps, foul odors, and foreign substances were reported when new owners took over.

Although the experiences of the new owners were dismissed as false, the site still brings visitors hoping for a paranormal experience. These visitors are drawn the experience of the supernatural; something abnormal and other-worldly. Perhaps they are there to confront not only the fear of death, but the possibility of life after the death, and the power that a bodiless spirit could retain.

Whatever the reason, the legend of the Native American burial ground still fascinates us today. We seem to be drawn to the power and possibility of life after death as well as the potential the “spirit world” has to disrupt our own lives. Perhaps we are also drawn to the mystical religion of the Native Americans that seems both foreign and palpable.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

College AU Headcanon for starters

Okay my little turtle doves. I’ve made a headcanon for the college AU. This will give you details and a bit of back story to explain all of the relationships in the story!! It’s long soooo Enjoy under the cut!!!

University of Vesuvia

You!

English major (I think this is simple enough to appeal to all)

Joined Flora and Fauna club to be around Muriel alone

Go to Cat Café's with Portia

Movie nights with Asra

Catch Julian in his plays and talent shows

Lunch/Brunch with Nadia off campus

Sport events with Lucio

Youngest

Average student, everyone helps you study

Extremely organized

Plays piano and loves to sing

Should be a sophomore with everyone else but took a year off after high school, wasn’t ready for the stress of college, too scared of failing

THUS you are a freshman baby child

Asra

Art major with English minor

Roommates with Muriel and Julian

Works at coffee shop in the library

Good grades even though he’s always last minute with his work

Teachers adore him

Everyone adores him actually

Only person that doesn’t like him is Lucio

Lil unorganized but always finds what he needs, has a method to his madness

Your best friend since middle school

Only went to school cause his parents wanted him to and to stay around his friends

Can’t wait for you to graduate high school so you can come and be at UoV with him!

Very spiritual, hippie type on campus

“You got a juul?”

Plays guitar

Sophomore

Nadia

Transferred from Praka University

Double major in Anthropology and Arabic

Roommates/Best friends with Portia

Multicultural sorority president (Kappa Zeta Mu)

TA

Lucio is her ex

Teachers pet

Everyone’s too intimidated to speak to her but she’s nice

Muriel thinks she’s nice

Someone always offers to carry her books but she’s too nice to let them do it

Super involved on campus, has a lot of friends

She’s just known on campus, like if you describe her someone will pop up like “You’re talking about Nadia? I love Nadia? Her close friends get to call her Nadi! I wish I could call her Nadi!”

Charming and admirable, it was surprising that a transfer student quickly joined a sorority and became the president

Went to college to get away from family and wants to be valedictorian

Junior

Julian

Biology Pre-Med major

Asra is his ex, they dated during freshman year decided to dorm together for sophomore year but broke up over summer. Neither could afford to change rooms.

Not good friends with Muriel, but doesn’t hate him

Theatre club, always the understudy for lead roles in plays, never gets a real part

Works part time in a research lab on campus, won’t prioritize his job over theatre club. Fights with professors to keep his job and cleans up the lab at the end of the night to make up for missing real shifts.

Julian gets all A’s and B’s but stresses when he doesn’t get a perfect 100

You become friends with Julian after an organization fair and he kinda projects on you and spills all the tea on his relationship with Asra and you two bond over having a mutual friend

Extremely unorganized can never find anything he needs, when he does find it, its covered in coffee mug rings and messy hand writing

Teachers scold him for his messiness but they all really care about him and commend his effort, as messy as he is, he’s the smartest in class and participates the most. Teachers favorite, really close with them.

Does not want any part of Greek life

One man play in the talent show, comes in second

Plays violin

Graduated early from high school taking college level classes, so he’s a Junior but supposed to be a Sophomore

Muriel

Psychology Major

Works part time in the library, its quiet, he’s tall enough to reach books and he loves to read

Flora and Fauna club!

Best friend is Asra, doesn’t really know you even though all lived in the same area. Knew Asra since elementary school but they split up after middle school, kept in touch through letters

Hates Julian, didn’t like his relationship with Asra. Knew he deserved better.

Book worm, hates real people but loves fictional ones

Thinks you’re alright. Surprisingly speaks to you, Julian doesn’t get why he’s not liked

Sneaks you books out of the library

Extremely organized, has a notebook for each class. Sits in the back never participates during lecture. Asks his questions at the end once everyone’s left or emails the teacher

HATES Lucio, you’ll know why

Plays around on Asra’s guitar but doesn’t actually know how to play, just does some simple plucking

Junior

Portia

Culinary Arts Major

Member Kappa Zeta Mu

Roommate/Best Friend is Nadia

Super outgoing

Always talking to someone on campus, even if they don’t know her

Pretty good grades

Works in the coffee shop with Asra, doesn’t really bother him about his relationship with Julian

Wants you to join every club she’s in so you can make friends

Cat Club! Cat Café's. Has a cat in her dorm even though she’s not supposed to

A lil messy, but she always gets her work done on time and gets good grades and praise from professors

Always dragging you out to some event but accidentally leaves you alone because she’s so outgoing and has hella friends

Portia calls Lucio’s frat All Body Odor (you’ll see why), what a silly goose

Sophomore

Lucio

History Major

Wishing he could just major in war, that’s the only part of history he likes

Really into his ancestry, traced it all the way back to prehistoric times some how

His ancestors are fairly boring until he finds he comes from a tribe called the Scourge of the South. South of where, he doesn’t care but they sound cool

They were warriors and he loves it. He wanted to know all of his “friends” ancestry too so he traced there's as well. Found out his ancestors, the Scourge, destroyed and made Muriel’s ancestors split and flee in all directions. Always teases Muriel about it, as if it really matters in modern times

Only became a TA to get close to Nadia again

Fraternity president (Alpha Beta Omega) [You get it now? ABO is All Body Odor! Portia is childish like that. What a silly girl!!!!!]

Always throwing a party

Extremely unorganized but doesn’t really care, gets his stuff in at some point, get’s good grades some how

“Professor Vlastomil won’t fail me! He loves me!”

Want’s “Jules” to join his frat, makes him carry his books and help him with his work

Always gets a latte from Asra’s coffee shop just to be in his face and bug him. Even though Asra purposefully messes up his drinks he always goes back for more

Teases you without mercy, likes that you tease right back. That makes things interesting. 😉

Junior

#hc#fic on de way#the arcana#the arcana game#college au#university of Vesuvia#YOU#asra#nadia#julian devorak#muriel#portia devorak#lucio#headcanon#mine#original

171 notes

·

View notes

Link

In the sticky, muggy heat of summer, it seems like every movement can make you sweat. As beads of salty water appear on your forehead and your shirt starts to stick to your back, you might run to find the nearest air-conditioned room.

But when Yana Kamberov’s three-year-old twins begin to sweat, she just smiles.

Yana Kamberov wants to understand how and why humans ended up with such hairless, sweaty skins.

CREDIT: Y. Kamberov

“I like sweat,” she explains. Kamberov works at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. As an evolutionary biologist, she studies how animals evolved over time. And when she sees her kids sweat, she knows that they are activating a trait humans evolved to keep from overheating. “You’re built for this,” she says. “The reason you don’t overheat and die is because your sweat glands activate to cool you off.”

To anyone trapped in a crowded space filled with stinking, sweaty people, Kamberov’s enthusiasm might seem a bit bizarre. But she’s not alone. Sweat fascinates scientists the world over.

Some, such as Kamberov, want to know where we got our sweaty skin. Others are trying to put our natural stank to good use. They’re out to track your health — and even catch a killer or two.

Sticking up for sweat

Kamberov didn’t always have such an appreciation for perspiration. As a teen, she wanted to be an archaeologist — someone who studies human history. “I’ve always liked history,” she explains. “I like to know where things come from.” But when she took a class on archeology in college, the shine wore off. “I didn’t want to chip stone in a desert somewhere,” she says. “It’s just not me.”

Instead, Kamberov realized she was fascinated with the history of humans as a species. She wanted to combine her love of biology (studying living things) with anthropology (the study of human culture). Her ultimate goal was to find out how humans as a species came to be.

Part of what makes our species what it is today, she soon realized, is how people look. “We stick out like a sore thumb among primates,” she says. Humans are often called the naked ape. Even the hairiest people lack the thick mat of fur seen on apes such as chimpanzees and gorillas. We have hair, and plenty of it. But the strands are thin. That leaves our skin exposed — and covered in sweat glands.

Explainer: The bacteria behind your B.O.

Three types of glands dot our skin. They release secretions onto the surface. Sebaceous (Seh-BAY-shuhs) glands appear mostly on our face and scalp. They put out oily chemicals that moisturize the skin and hair. They also help waterproof the skin. A type of sweat glands known as apocrine (APP-oh-kreen) cover our armpits and genital regions. These glands secrete a thick substance full of fats. Bacteria feed on those fats, at the same time producing the smell we lovingly call body odor.

But eccrine (EK-kreen) glands dominate most of our skin’s real estate. They produce the watery, salty sweat that helps the skin cool off. These glands show up everywhere from your feet to your scalp, and appear as neighbors to those sebaceous glands on your face, and the apocrine glands in your armpits and genitals. The only places people don’t have eccrine sweat glands are on the skin of their lips and nipples.

Explainer: What is skin?

And wow, can humans pump out sweat. Even when relaxing at home, people produce about 500 milliliters (just over 2 cups) of sweat per day. But when working out in the heat, people can pump out up to 10 liters (2.6 gallons) of the stuff. “Our mechanism for cooling ourselves off is to sweat,” Kamberov explains. “In order to do that we have an enormous abundance of sweat glands.”

Those sweat glands are connected to nerves. The nerves are controlled by a part of the brain called the hypothalamus (Hy-poh-THAL-uh-muhs). It sits at the base of the brain, roughly behind the bridge of the nose. It senses when our body temperature is rising, such as when we exercise or step outside on a hot day. When the heat is on, the hypothalamus signals our eccrine glands to rev up.

As they spring into action, they suck water and salt from the spaces between our cells. The liquid collects in the gland. Pumps there will force out most of the salt. The remaining watery solution squirts out onto the surface of our skin. There, wind and air evaporate the sweat — along the way removing some of the body’s heat.

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gnosticism Still a Challenge to Christianity

Gnostic philosophy, like a noxious weed, thrives in the barren soil of our post-Christian culture. It also emits a foul odor akin to the smoke of Satan, filtering through the doors of the Church and influencing our anthropology, as well as severely compromising the integrity of our worship of Christ in the Eucharist.

Catholicism is incarnational. Reverence and respect for the body is central to our worship and our way of life. Unfortunately, Western culture has in many ways devolved into a form of Gnosticism: an anti-incarnational, dualist ideology of the separation of body and soul. Gnosticism is a false spiritualism that values the soul or the mind as the true self. It denigrates the body as an object, a lesser creation, an encumbrance for the soul, or it treats the body as raw matter to be manipulated by the will.

In the Catholic understanding, human beings are not souls who “have” bodies as objects; rather, we are subjects with a body-soul unity. Thinking we “have” bodies can lead us to live in our heads, disconnected from our bodies.

Gender identity is the most obvious example of the influence of Gnostic concepts on our culture. Some people actually believe they can have a gender identity in their minds which is the opposite of the gender of their bodies! Such people are clearly suffering and in need of compassion, but the absurdity of gender ideology is an indication of the degree to which we human beings are capable of dissociating from the reality of our bodies.

Technology can reflect and reinforce these harmful Gnostic ideas by perpetuating a tendency for us to over-identify with our minds. The Internet allows for more instant communication over vast distances, with the unintended consequence of removing us from our immediate environment. A stroll down any city block will confirm this observation. People will be so absorbed in their smart phones that they find themselves completely alienated from their surroundings and from other people. Hours spent on mass media can deeply affect the psyche, creating a habit of living in a purely mental and virtual world, separated from the reality of the body.

In the Eucharist, our communion with Christ is vitiated by this habit of living in our minds, detached and dissociated from our bodies and the present moment. If we are not present to ourselves in our own bodies, how can we be present to the Body of Christ in the Eucharist? Christ is truly present but we are not. It is like someone who is so busy and distracted that he shakes hands with someone without looking him in the eye. It is an empty gesture of friendship. Patiently and unfailingly, Jesus stands at the door of the heart and knocks, but there is no answer, because no one is home. The person is so distracted and dissociated he receives the sacrament of the Body and Blood of Christ as a piece of bread, rather than as a living Person.

In the Catechism, on the section pertaining to the struggle for prayer, we read, “the habitual difficulty in prayer is distraction.” Such lack of attention in prayer is a common, normal aspect of the human experience. However, when distraction deepens to the point of dissociation, we are on the verge of an experience of disembodiment, which severely limits our capacity for prayer and communion with God and others.

I believe we need to bring to light our unconscious collaboration with Gnostic ideas; in our pride and fear, we often prefer to live in our minds rather than in our bodies. Our minds can provide us with the illusion of power and control. Our weak and limited bodies remind us of a reality that many of us find unpleasant and distasteful, to say the least — that we are contingent mortal beings entirely dependent on Another for our very existence at every moment.

But it is only in and through our poor, weak, mortal bodies that we truly worship and enter into communion with Christ in his Body and Blood. Christ took on a human nature so we could have communion with his Divinity through our humanity. And Christ as God embraced his human nature more than we do! He was not ashamed of his human poverty and weakness. Yet so often — far too often — we are ashamed of our humanity, and we desperately want to escape the limits and sufferings of our human condition. But then we have no real embodied communion with Christ.

Jesus is our model for embodied worship. In his Incarnation, when he came into the world in the womb of Mary, he said to the Father, “A body you have prepared for me… Behold, I have come to do your will, O God.”

Christ was not only pleased to become little and helpless as a child, he also consented to suffer incomprehensible pain in his human body in his Passion. He could have chosen to dissociate from his body through ecstasy, a grace given to some of the martyrs who were miraculously spared the full brunt of their sufferings. But Christ refused to drink the wine mixed with myrrh, a narcotic painkiller, because he chose to enter into the full agony of his Passion, to empty the chalice of his suffering to the last bitter dregs.

Most amazing of all is his Resurrection from the dead in a human body. He did not rise as a pure spirit, leaving his body behind. He ascended into heaven in his body. He is now seated at the right hand of the Father in his body. With that same glorified human body, he lives and reigns forever and ever, world without end.

By his Incarnation, death and Resurrection, we are healed. Through Christ’s permanent and irrevocable “association” with his body, he heals our dissociation. By his embodied existence and worship, he enables us to lovingly embrace our human nature and to worship reverently with our whole being. Through our full, active, conscious, and embodied participation at Mass, we can experience more deeply the Eucharist as the source and summit of our faith. Then we will be empowered to announce the Gospel in our secular culture. In the words of St. Paul, we will spread the “good odor” of Christ, displacing the poisoned air of Gnostic fallacies.

BY: FR. TIM MCCAULEY

From: www.pamphletstoinspire.com

1 note

·

View note

Text

ncfan listens to The Magnus Archives: S1 EP017 (’The Bone-Turner’s Tale) and S1 EP018 (’The Man Upstairs’)

Body horror and another episode that reminds me of Ito Junji’s work. Not a good pair of episodes for people with weak stomachs.

No spoilers past Season 1, please!

EP 017: ‘The Bone-Turner’s Tale’

- Sebastian’s gushing about the power of books is kinda sweet, though the power we see displayed in this episode is anything but. (And I happen to have in my possession a few books—not first editions, of course—that have outlived the societies that produced them, so I get the wonder on that account.)

- And Michael Crew (mentioned in ‘Page Turner’) has snuck another Evil Book into an innocent Chiswick library. What the hell, man?

- And we get static when Jonathan reads out the title of the book—‘The Bone-Turner’s Tale.’

- Jared Hopworth sounds like a piece of work, though the fact that he still seems so fixated on a guy who was his friend and now he seems to want to believe he hates is a little… sad. I doubt Sebastian felt much, if any, sympathy for him, but I suppose that as a listener, I can feel sorry for him. Or, at least, I feel sorry for him now. All sympathy dies soon.

(And I’ve since learned that I was mishearing the name ‘Gerard Keay’ as ‘Jared Key.’ Personally, in Sims’s voice the names ‘Jared’ and ‘Gerard’ sound frankly identical, but okay. I’ll call him ‘Gerard’ from now on to avoid confusion.)

- And we have an intermission and our first proper introduction to Elias, where he proceeds to tell us just how badly Jonathan’s first attempt to interact with a statement giver went. And that the creepy, creepy Lukas family is one of the Institute’s patrons. I’m sure that’s not a bad sign at all.

- “I’ll… be more lovely.” No, you won’t.

- Yes, I’m just sure Martin’s off sick. Normal sickness, being shut into your apartment by a living hive of flesh-eating worms.

- Sebastian, I understand not wanting to create unnecessary drama, but it might be better to tell your coworkers if someone’s harassing you if you think there’s any chance he might drag them into it as well.

- It’s odd that Jared would walk off with the book even if he seems a bit frightened by it. Some sort of compulsion, perhaps? Or maybe he’s run into Michael Crew before and recognized a book that had once been in his possession.

- The thing with the poor rat is the reason why I will not be revisiting this episode, not unless I just do a big re-listen of the series in general. It’s also the thing that completely evaporated my sympathy for Jared (Even before we saw what he did to his mother). That was his pet, an animal without any significant ability to hurt him in its own defense the way a cat or a dog could. It probably trusted him unhesitatingly, didn’t even consider Jared might hurt it until he did. And I know a lot of people don’t like rats, but tame rates make for really cute, cuddly, affectionate pets. I do mean affectionate—they have the same capacity for empathy and bonding with owners that cats and dogs possess. And Jared did that to it. I will not go out of my way to listen to this episode again for the very simple reason that animal cruelty, especially cruelty towards your pets, turns me right off.

(I probably would have scooped the rat up and taken it to the vet once I realized it was a tame rat. Of course, given the state it was in, probably the only thing the vet would have been able to do was euthanize it so it wouldn’t suffer any more than it already was. But I can understand Sebastian not wanting to pick up a strange animal.)

- I can understand Jared’s mother taking her anger out on Sebastian. It’s probably a lot safer being angry at him than at Jared, considering the new skill Jared’s picked up. I note we never see her again after she presumably steals the book to take it back to the library. I doubt that bodes good things for her fate.

- We get static again when Jon reads out the title of the book.

(I listened to the first episode again today, and there was static when Jon read out the “Can I have a cigarette?” spoken by the entity of the episode, too.)

- I was curious as to whether pseudo-Chaucerian tales were a thing, and sure enough, it turns out that during the Medieval era it was for a time the fashion to write pseudo-Chaucerian tales in an effort to “finish” The Canterbury Tales. Some people decided to add on to the Cook’s Tale, which Chaucer died before he could complete, or to write new ones whole-cloth. One is called The Plowman’s Tale, another is called The Tale of Beryn.

- It’s a pity the thing with the rat affected me the way that it did, because the rest of the story is quite engrossing.

- And ‘The Bone-Turner’s Tale’ is so evil it makes other books bleed. That’s… definitely something.

- And we get static when Sebastian describes the books bleeding.

- Sebastian pointing out how ambiguous it is as to whether the bone-turner is traveling with the other pilgrims or if he’s just following (stalking) them feels… right, for this kind of series. Horror thrives on ambiguity, on puzzles where there’s just enough empty space or there’s a couple of pieces missing, so we don’t know what the whole picture is supposed to look like.

- The fact that the technical quality of the prose is mediocre is oddly hilarious. Because, you know: evil book that gives people the ability to manipulate bones.

- More static when Sebastian quotes the book.

- Why am I not surprised it’s a Jurgen Leitner book? From now on, I’m just going to assume that any weird book that shows up in this series is a Leitner book.

- The description of Jared’s “modifications” is excellent. Especially the extra limbs and the ribcage modified to be a mouth. Pushing the boundaries on what counts as human, aren’t we?

- I wonder how Jared was running. Was he scuttling along like a giant spider, or something?

- I do wonder what the cops (and the library staff, for that matter) thought about the bloody books. How do you look at something like that without having some kind of comment?

- And Jonathan is predictably rather ill with the thought of another surviving Leitner tome having slipped through the cracks.

- Yeah, Jared attacked and mangled Sebastian so severely that he died, and had a closed-casket funeral. I really doubt Mrs. Hopworth is still with us.

EP 018: ‘The Man Upstairs’

- Here’s another one that reminds me of Ito Junji’s work.

- I understand that in the U.K., the floor numbers in buildings go top-bottom, instead of bottom-top. At least, that’s the impression I’ve gotten. So the fact that Toby Carlisle is said to live on the first floor I take to mean that he lived in what in the U.S. would be called the second floor.

- The smell Christof associates with Toby in the beginning—a combination of pavement after rain on a hot day and spoiled chicken—makes me wonder when exactly Toby started nailing up the meat. Did he start small at first, so that you’d only notice if you got a whiff of it through an open window or door? Or was it his association with the entity in question that made him smell like that—did he just carry the odor of decay with him wherever he went?

- It’s interesting that Toby did the hammering meat onto the walls once every two weeks, on the dot. Did he have a schedule he had to keep to?

- The description of the carpet in front of Toby’s door… ick.

- Interestingly enough, I think we got a little bit of static when Toby said “What do you want?” Do the distortions extend to human agents of the entities we’ve seen in the series?

- Oh, God, I’ve finally figured out what the viscous, off-white liquid seen in the episode is. It’s liquefied fat, isn’t it?

- The plumber’s visit… You know, my senior year working towards my anthropology degree, the washing machine in the dorm above the one my roommates and I lived in broke down and flooded the upstairs dorm—and ours, too, eventually. I can’t begin to describe how fortunate I feel right now that the only thing that came pouring out of the light fixtures in the kitchen was soapy water.

- The interior of Toby Carlisle’s flat, this is what reminded me of Ito Junji’s work. Can’t you just imagine him drawing something like this? I’m pretty sure he has drawn something at least vaguely similar to this before; I’d go and check, but that would require me to look at it again, so no, thank you. (I think it was in a oneshot manga called ‘Greased.’ Only vaguely similar, but way too similar for me to want to look at it.)

- The description of the flat is actually quite good. Probably the only reason I can deal with it is because I don’t have to look at or smell it.

- Was… Toby trying to summon some kind of meat entity with this nailing up meat all over his flat? Was that why the meat thing with all the eyes was in the kitchen? And I suppose it just sort of winked out of existence when it realized it had been spotted.

- “It opened its eyes. It opened all its eyes.” I’ll… just leave this here.

- It’s interesting that the cops, the fire department, and the hospital all give such different accounts. I would have liked to see what the inconsistencies entailed. I feel like that could be very telling.

- I’m glad Christof got some counseling.

- I think the stinger in this episode is the best one up so far. Where was Toby getting all the meat?

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Are you nervous?"

I took a deep breath. "I’m not."

"That doesn’t sound believable to me," the man said. He fixed my collar, zipping it up and bereaving me of the cool air. "We can’t have you fumbling around on your first day, now can we?"

His eyes weren’t seeking a confirmation, nor were they focused on mine. They tracked my movement as if he was inspecting me for bugs.

"I’m fine," I assured, pushing his hands away. The gent patted my clothes and rubbed them down, removing folds and dusts from the pure white in silence. He accompanied me throughout my trip, but ignored the question pertaining to his identity when I brought it up earlier. His fingers fumbled with my bangs, annoying me but he was older than me, and I had a hunch there was more to him than I could inspect now.

"You should trim it," he said, gazing over my strands. His intentions were unreadable from his voice. I had expected interesting and brilliant men, bizarre, but geniuses. But he excelled in averageness.

Sharp dressed, handsome, but nothing defining.

The cubicle grew tighter, and I heard a crowd through the walls. My hands clenched my sides, wiping away the excess sweat as my composure was wavering.

"Have you ever been in an airport, Nex?" he asked, redirecting his attention to the door. "I haven’t."

"Feast your eyes."

Buzzing filled my ears as the door dropped and placed me in the front of a bustling room. Men in coats, uniforms, all sorts of fancy brisked past me, assistants tailing them. The sun shone brightly and illuminated the place, the reflections of the polished hub stunning me. The dome rotated, no, seemed to rotate as the projections changed. My companion stepped forward and shook me out the daze.

"It was nice talking with you. Go register at the desk," he gestured. "Unfortunately I'm a busy man so please excuse me now. See you later," and he pushed me from the platform.

"W-wait, where do I-" I started, but as I turned my back, the lift and the man had disappeared. Vanished with the wind. I wonder who that was.

By no means was I shy, but the consistent marching, serious faces and short replies intimidated me. My breath fell short as I was confronted with the most humans I had ever seen in one place. I might have felt less inclined to stare if it wasn't for my bangs, but I couldn't help observe the figures running about. A ruckus at one queue was especially intriguing.

"Let me pass! I'm a faculty head!" a spright young man demanded. The bright parakeet on his shoulder caught my eye, and he seemed out of place between the men in white coats.

"We are under direct command of boss. Please respect his decision to have his faculty members hold his spot." one of the white coats repeated multiple times.

"Holding a spot in a communal used queue is not acceptable. Do I have to remind you of your position?" the man fumed. He was dressed casually, and looked a little young, but his posture screamed confidence as his hair twitched in bursts.

The white coats mumbled amongst themselves, leaving twitch hair stampeding his feet.

"We can't disobey boss. He'd dismember us."

"Dissect us."

"Decimate us."

The man radiated his displeasure and took out his phone, scrolling and swiping with force, glaring big trouble at his obstruction with the phone pressed against his ear.

"Excusez-moi!"

Someone bumped my back, and I stumbled forward. "Merde," he cursed, dropping his phone. He stared me down, and I felt strangely obligated to apologize so I crouched, but before I could even reach out he snatched the phone and walked away. "Fucking tourists."

Feeling self-conscious, I got a move on and went to the checkpoint which was sparsely populated. A man in immaculately shiny glasses looked down upon me.

"Pass."

"Huh?"

"Pass."

"Identification papers. You are a new discipline, correct?" he forcibly smiled.

I blanked out. Aside from the clothes and that, I possessed no such papers.

"The ones you received upon your acceptance?" he asked, procuring a mock copy from behind the curtain. Deftly flipping them, he sighed and put them away when he saw (or did he sense) my confusion.

"Do understand I can't let you pass. Please stay in this zone and consult our trouble desk for lost documentation," he continued, and pointed to the rickety shack a few meters past. Seemingly unmanned. One ring of the bell. Two rings. I gave up after the third and leaned over the counter, but no officials in the vicinity to grab their attention.

"Now don’t go trespassing there kid," a voice called out. A boy, maybe a man, strode up, lacking the formal attire or fancies, but with a significant poise that piqued my curiosity. He sported the same kind of glasses the desk worker had, but seemed less uptight with his striped socks beneath his oversized pants.

In hindsight, he was helpful.

"I have trouble with my documentation sir," I replied, "currently awaiting service."

"Newbie?" he asked, raising a quizzical eyebrow. "You’re not a mortal I hope?" he said, hands on hips, leaning forward. He wasn't scrawny, not a huge guy either- there was something about his slender body that was flowing but frail.

"I don’t think so," I said. He observed me, circling much like the other sir, assessing my qualities while hunching over. He had a peculiar smell, a certain richness to him, that accompanied his looks, a vague, chocolate odor. "Are you perhaps a new computer language," he guessed.

"Yes. I'm called Nex, and finished development 5 years ago, qualifying for a class at a prestigious college a month back."

The man paused and his eyes widened up so big that I could see my reflection. "Are you only 5 years old Nex?"

I stepped back, intimidated by his sudden closeness.

"That is amazing!" he squealed, before closing the gap to rub my hair. I chewed my lip, but by all means, he was still my senior.

"Nice to meet you kid! Lately we've been receiving many of your digital kind, but you’re still a little mayflower. Tell me a bit about your founder, will you?"

He got a device out and pushed it in my face, startling me when it flashed my face. "F-founder? My founder was an intelligent person. As most should be." I answered with dignity.

"Wow, wow," the man exclaimed, waving his hands in the air. "Aren't you jumping ahead of yourself, kid? Geniuses, yes, but also madmen, are who enabled us to exist.

Well, she was a special case, but to call her mad was an over exaggeration.

"By the way, aren'tcha wondering who I am?" the man prodded, moving the recorder obnoxiously at random, almost hitting my face. "You're really curious, right?"

"I can't deny that," I admitted. "Connections are important," is what my founder always said, when she forced herself in tight suits to garner even the slightest of respect from her peers.

"My name is the almighty Anthropology," he bowed. "Humans call me Anton."

"Greetings sir Almighty Anthropology. Which faculty do you belong to?"

Beat. He stared, then smirked and patted my head. Did I say something strange?

"I'm a faculty head kid."

"Oh," I answered. That sounded impressive (although I didn’t quite realize the implications until later) and important to build my connections.

"You're quite airheaded for a computer language, aren't you?" Anthropology sighed, grabbing my shoulder. "Do you even know what I am or what I do around here?"

"I don't sir."

"Kid. Strap up and prepare for the ride of your life," he said, motioning for me to follow him through the gate.

I’m Nex.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Human decomposition is a natural process involving the breakdown of tissues after death. While the rate of human decomposition varies due to several factors, including weather, temperature, moisture, pH and oxygen levels, cause of death, and body position, all human bodies follow the same four stages of human decomposition.

WHAT ARE THE FOUR STAGES OF HUMAN DECOMPOSITION?

According to Dr. Arpad A. Vass, a Senior Staff Scientist at Oak Ridge National Laboratory and Adjunct Associate Professor at the University of Tennessee in Forensic Anthropology, human decomposition begins around four minutes after a person dies and follows four stages: autolysis, bloat, active decay, and skeletonization.

Stage One: Autolysis

The first stage of human decomposition is called autolysis, or self-digestion, and begins immediately after death. As soon as blood circulation and respiration stop, the body has no way of getting oxygen or removing wastes. Excess carbon dioxide causes an acidic environment, causing membranes in cells to rupture. The membranes release enzymes that begin eating the cells from the inside out.

Rigor mortis causes muscle stiffening. Small blisters filled with nutrient-rich fluid begin appearing on internal organs and the skin’s surface. The body will appear to have a sheen due to ruptured blisters, and the skin’s top layer will begin to loosen.

Stage Two: Bloat

Leaked enzymes from the first stage begin producing many gases. The sulfur-containing compounds that the bacteria release also cause skin discoloration. Due to the gases, the human body can double in size. In addition, insect activity can be present.

The microorganisms and bacteria produce extremely unpleasant odors called putrefaction. These odors often alert others that a person has died, and can linger long after a body has been removed.

Stage Three: Active Decay

Fluids released through orifices indicate the beginning of active decay. Organs, muscles, and skin become liquefied. When all of the body’s soft tissue decomposes, hair, bones, cartilage, and other byproducts of decay remain. The cadaver loses the most mass during this stage.

Stage Four: Skeletonization

Because the skeleton has a decomposition rate based on the loss of organic (collagen) and inorganic components, there is no set timeframe when skeletonization occurs.

BODY DECOMPOSITION TIMELINE

24-72 hours after death — the internal organs decompose.

3-5 days after death — the body starts to bloat and blood-containing foam leaks from the mouth and nose.

8-10 days after death — the body turns from green to red as the blood decomposes and the organs in the abdomen accumulate gas.

Several weeks after death — nails and teeth fall out.

1 month after death — the body starts to liquify.

source: https://www.aftermath.com/content/human-decomposition

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

h8rs will see u adn say