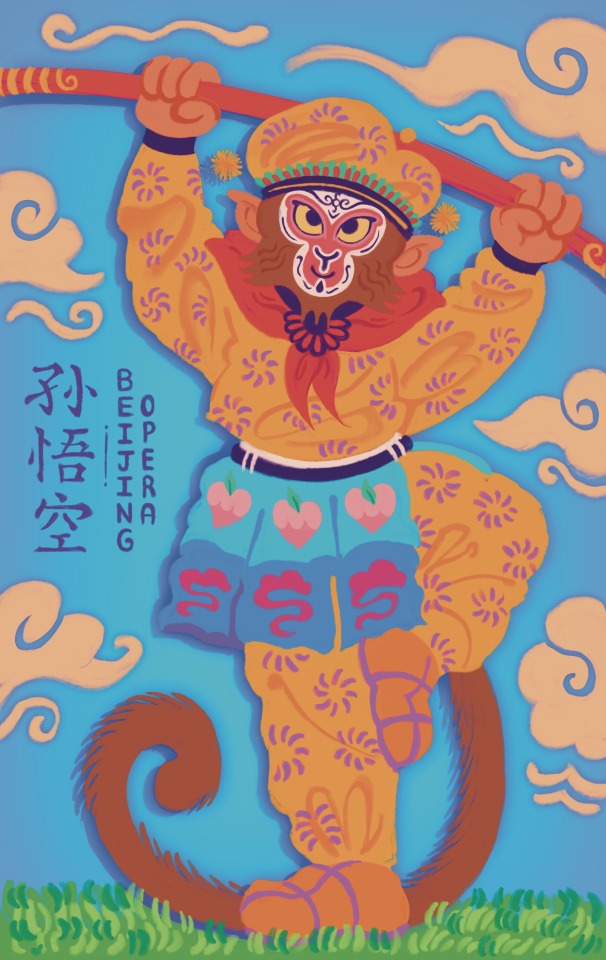

#beijing opera sun wukong

Text

I ❤️ you monkey king(s)

#sun wukong#monkey king#jttw#jttw 1996#monkey#beijing opera#beijing opera sun wukong#swk#journey to the west#journey to the west 1996#i love sun wukong#illustration#sun wukong..... ❤️#monkey enthusiast#happy spring break!!! i will open comms soon *u*

748 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi there! unsure if this has been asked before, but where is your header from?

I found the picture randomly on the internet. But as luck would have it, I actually met the actor in November 2023 during a yearly Monkey King Temple trip in Taiwan. Yuta Ishiyama is a Beijing Opera-trained Japanese actor who specializes in playing Sun Wukong.

Here he is holding his personal Great Sage idol in a procession.

#Sun Wukong#Monkey King#Journey to the West#asks#Lego Monkie Kid#LMK#JTTW#Chinese opera#Beijing opera

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Beijing Opera of Wukong trying to borrow the Plantain Fan from Princess Iron Fan!

no English subtitles unfortunately, but the action is worth it and my god the funny bits still come through xD

#jttw#journey to the west#xiyouji#sun wukong#monkey king#princess iron fan#beijing opera#chinese opera#Youtube

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Made my way through the first half of the Havoc in Heaven Beijing Opera, and while I don't know Mandarin I'm finding it a fun time not only because of the acrobatics and music and the way the Monkey King & the Mt. Huaguoshan monkeys were allowed to go full silly with it but also because this Sun Wukong is a fashion icon, as is only his right:

#jttw retelling#beijing opera#chinese opera#sun wukong#monkey king#mt. huaguoshan monkeys#always fun too to see a retelling where swk spends his time kicking someone who insulted him around & hanging out with his monkey family#he's having so much fun here & it's a delight to see

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nezha Reborn annotations - Part 2

Part 1|Part 3

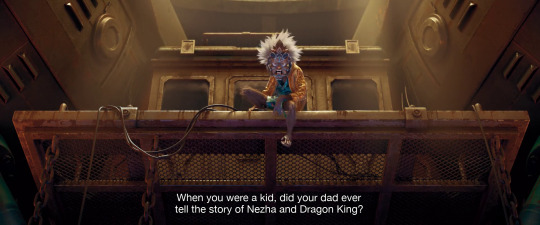

Monkey asks Yunxiang whether his dad ever told him the story of Nezha conquering the dragon king when he was a kid. Most Chinese people will probably remember this story from the 1979 animation of the same title that was adapted from chapter 14 of Investiture of the Gods.

More product displacement: Smirnoff, what looks to be Suntory Royal and if you zoom in on the Jack Daniels, it reads “Made in Light Chaser” lol

Primordial Spirit or “god-body” is something you’ll see a lot in the New Gods universe. Known in Chinese as yuanshen (元神), it is a concept in Daoism defined to be a level of existence surpassing that of physical existence, capable of existing independently in the form of a soul. It is viewed to be the center and essence of a human's existence.

Monkey breaks the fourth wall

This quote comes from Liu An’s poem Nüwa mending the heavens (女娲补天), delivered Peking Opera style, down to the mannerisms. The caged bird could be a thrush or a lark. Bird keeping is a traditional hobby in Beijing that started in the Qing Dynasty and songbirds were usually kept in these cylindrical cages.

I shouldn’t have laughed so hard when he accidentally killed the glasses monkey and continued his business like nothing happened.

“Fire imp” (葫芦老四) is the fourth of the seven Calabash Brothers, a classic Chinese cartoon from the 80s. Each bro has a unique power, and bro #4’s power is the ability to control fire. The snake demoness is an integral part of that story, so Light Chaser’s White Snake movies might actually be set in the same universe?????

Chan and Jie are religions featured in IOTG. Chan Daoism was founded by Yuanshi Tianzun (Primeval Lord of Heaven) and Laozi, and Yang Jian is one of its disciples. Jie is a fictional religion headed by Tongtian.

The most unfortunate character in this movie has got to be this monkey.

“Are your training methods even legit?”

Where did he get so much water? I thought water was being sanctioned.

RIP this monkey again.

He built his own version of Nezha’s spear.

The Six-Eared Macaque is arguably the most dangerous antagonist in Journey to the West. This deceptive creature impersonated Sun Wukong after the Monkey King abandoned his pilgrimage following a tiff with Tripitaka, with the impersonation so perfect, only Gautama Buddha and Diting could see through the pretense.

Nezha’s primordial spirit manifests as his three-headed, six-armed form.

Nezha is traditionally depicted with his four Astras - the Wind Fire Wheels (风火轮) under his feet, the Cosmic Ring (乾坤圈) around his body, the Sky Ribbon (浑天绫) around his shoulders and a Fire-tipped Spear (火尖枪) in his right hand.

This man has gills.

The Yaksa Li Gen is described as a lizard like creature with long mercury red hair, protruding fangs, and a face the color of indigo. (IOTG chapter 12).

Netflix's thirst trap of a thumbnail is from a scene that lasted ONE WHOLE SECOND.

It’s hilarious how this guy was just credited as “the traitor”.

The art deco style of the crystal palace 👌

In 2013, archaeologists unearthed a 1000 year old statue in Sichuan in that depicted a beast resembling a rhinoceros. This was believed to be the water-suppressing mythological beast Zhenshui Shenshou (镇水神兽) that was documented in the Biography of Shu Kings Written by Yang Xiong in Han Dynasty.

“I taught him? I don’t even have disciples! Stop joking.”

Dragons kind of have a low status in heaven (no matter how majestic they are, they are still beasts and all beasts are looked down upon by the gods), unlike in the mortal realm where they are revered.

Even in his dragon form, Ao Bing’s spinal column is supported by metal bracing.

Part 1|Part 3

155 notes

·

View notes

Photo

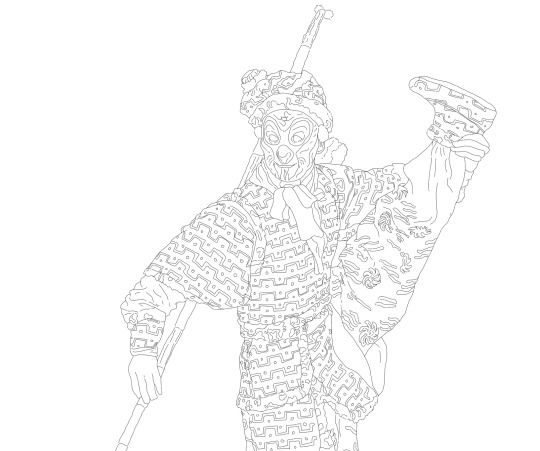

I scanned this picture because I’m afraid that chances of f*cking it up in the process of colouring are bigger than zero.

Peking Opera actor playing Sun Wukong redrawn from a stock image found on the Internet.

#sun wukong#journey to the west#jttw#monkey king#great sage#peking opera#beijing opera#chinese opera#xiqu#jingju#traditional art#dfzart#ink

148 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Self Actualization

#my art#journey to the west#jttw#xiyouji#sun wukong#monkey king#Chinese mythology#Chinese opera#Beijing Opera#Cantonese Opera#illustration#comic#using stage makeup as war paint is an aesthetic power move#I finished Winter Begonia and stopped in the middle of animating to draw this because i need more opera aesthetic!!!#anyways yeah listen to wukong's voice and tell me he doesnt want to be a wusheng#woke modern wukong job headcanon: opera teacher#anyways buddy ya got your red eye aesthetic but at what cost#mild eye trauma tw#translation: 生/sheng is the traditional 'dignified male' role in Chinese opera and 净/jing is a rougher less dignified male role*#*usually generals and stuff#*well not exactly less dignified but theyre less scholarly and stuff

696 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Eastern dramas vs Western dramas

Part 2: On Theatricality and how it transfers into Chinese/Eastern Dramas and Cinema

Part 1 Part 2

Here, I reference a fantastic article from the Asian Theatre Journal, 2008.

So to recap, the problem I’m exploring is this: Why do some East Asian dramas/movies look so over the top? Overacted? Overemotional? Why is it not more realistic?

My answer is in part 1, on the concept of mo, which is the traditional Chinese thought that emotional revelation is more important than accurate realistic depictions in art. Western audiences are more used to plot-heavy, realistic depictions of dramas, whereas traditional Chinese audiences are used to the opposite. They find the plot not so important, but focus more on the content of the work, the spirit of it, how it makes you feel.

1. How traditional Chinese drama translate into cinema/screens?

Making the jump from Beijing/Peking opera stages, or jingju, to cinema screens caused a lot of trouble.

a. Production-wise, early 1900s

It was difficult to adapt the very open, 3d stage into a “realist flat screen,” which was much more advantageous to Western eyes because the camera lens was invented based on “Renaissance principles of fixed point perspectives and foreshortening.”

b. 1950s-60s

Many still tried to adopt the Beijing opera style into film, but it was still very hard because the two mediums were so contradictory. Beijing opera relied on live, grand aesthetics along with the knowledge that the important aspect of drama was emotion and internal struggle, vs film at the time was very focused on accurate “mimesis,” or imitations of real life. One such example was critics actually laughing about the adaptations because the opera actors mimicked riding a horse in the traditional style - that is, minus the horse. Film would have them ride a prop or real horses.

Eventually, many changes were made to the style to better incorporate it into film, and it still kept a lot of its original roots (i.e. makeup/grandiosity in costume, emotions, etc). Western concepts of a limited stage, and emphasis on plot and tragedy were expounded upon. And eventually you have the modern-day dramas (1970s+).

2. Japanese Noh 能 theater - Kurosawa’s Ran

Noh is a Japanese form of theater that is a dance-based dramatic work. It tells stories of supernatural beings transformed into humans and etc. One of its major notes is its very stylized conventional use of specific gestures to portray emotions. Iconic, specific masks are used to portray the roles of the actors such as the ghosts, women, deities, and demons.

Akira Kurosawa’s Ran is lauded as one of the greatest films ever made. It’s a Japanese-French production heavily inspired by Shakespeare’s King Lear. There are many many detailed videos on YouTube about his precise filming methods and movement aesthetics. The body language can be seen as “over-acted” if you come from a Western background. Why? Because it takes from traditional Noh theatre:

Long periods of static motion and silence, followed by an abrupt, sometimes violent change in stance. Heavy ghost-like Makeup. Highly emotive gestures, sometimes repetitive to emphasize the characteristic of a character. All very unrealistic, but that’s not the point, right? Because this also displays mo, it takes the emotive expression, the revelation of fear/action/hope to the front of the stage.

3. Japanese Kabuki theatre - acting style is also larger than life

Kabuki actors also make great effort to express themselves in highly stylzed gestures (i.e. the men play women’s roles and over-act their femininity).

One major difference between Kabuki and much of Western theatre is that kabuki actors make less of an attempt to hide the “performance” aspect of the work. They’re fully aware that they’re performing, and the audience isn’t there to get “lost in the moment.” Everything -- actors, costumes, dialogue, is larger than life. Realism is far less emphasized, the form generally favoring what is often referred to as “formalized beauty.”

One example of this is the highlight of an aragato kabuki performance: the famous mie. The mie is a dramatic pose adopted by the main (oftentimes male) character during moments of emotional intensity. (The proper phrase for this action is mie o kiru, or to "cut a mie.") Announced by the beating of wooden clappers, the actor freezes in a statuesque pose and crosses one or both eyes. Often it's preceded by a head roll. The idea is to capture the highest moments of tension into one physical gesture and to more or less hold the actor and the audience in a breathless trance. After a few seconds, the actor relaxes and the play continues. A mie can be cut in various specified positions, depending on the character and the moment. When exiting, an aragoto character may perform a roppo exit, which combines several of these poses in rapid succession, before leaving the stage.

The mie pose

This is not to say that modern Japanese dramas and works directly descend from Kabuki or Noh or other theatrical traditions. But like the Chinese beijing opera, the concept of aesthetic beauty/mo, emotional revelation, these ideas all combined with Western influence and modern Western perceptions of good story-telling/acting to make up the modern Eastern dramas of today.

4. How do all of these things combine into the supposed “cheesy/corny/over-acting” of modern Eastern dramatic works?

All of these cultural roots combined with Western depictions of a modern story (i.e. Shakespearean tragedy in five parts: Exposition, Rising action, climax, falling action, and denouement, ofc there are other ones but this is the one I learned in school), I believe make up what we see today in modern Eastern dramas.

A. Acting Comedy: My specific examples are first, comedic examples from the famous 1986 Journey to the West

Comedy and the feeling of happiness and joy are also very important aspects of emotional revelation. Journey to the West depicts one of the most beloved comedic characters, Sun Wukong, who goes on a journey with Tan Sanzang, a Buddhist priest, to find the sacred Buddhist texts. His exploits are highly unrealistic and highly comedic. It is one of the epitomes of the “spirit” over the “form,” the internal emotional journey over the actual realism (or unrealism) of the journey. Many of the characters exhibit over-the-top facial expressions, some expressions too subdued, and the plot can be very winding and haphazard, but that’s not the point! If you’ve been reading this far, you’ll know why. It’s about how his adventures make you, the audience, the reader, feel.

B. Acting Villainy: More modern Chinese dramas i.e. The Untamed & Word of Honor

I cannot attest to the quality of the acting nowadays, but it’s a common idea that the supporting cast of the international hit, The Untamed, was a bit weak in terms of acting. If I were to step into my Western lens, I would agree that yes, many characters over-act (i.e. Xue Yang, below):

And Wen Kexing, Word of Honor:

And Journey to the West, Underworld Lord:

However, now with all that cultural context, I can see this choice of acting in a different light. The over-acting and depiction of villainy is over-the-top because it’s meant to inspire that emotion of (this guy is whack, like really). It’s not supposed to be realistic villainy, like how a real person would look if they were these people in real life. To judge it by a completely Western lens is doing a disservice to them I think. You could say that maybe they just can’t act well, but in a Chinese/Japanese/Eastern cultural theatrical context, their acting is actually par for course. It’s even more subdued than the traditional roots of Eastern theatrical performances actually.

This goes for many other C-dramas / Eastern dramas that have these instances of highly emotive performance. It’s a product of hundreds of years of Eastern cultural theatrical/artistic production combined with Western acting styles and cinematography.

Is it cheesy? Maybe. Is it over-acting? Could be, but what is “over-acting” vs what is “enough?” Is that not the distinction between mo and Western realistic imitation? For me, as someone who’s very used to this uniquely different style of dramatic production, I’m not too bothered by it. It, after all, makes me feel such an incredible range of emotions that the acting is just a fun, interesting perk.

Thinking that these dramatic productions were originally seen as extensions of poetry, I can see why the exaggeration is necessary to fulfill what mo means:

If I feel some intent, I must write it - it becomes a poem.

If that’s not enough, I must sing it - it becomes a song.

If even singing isn’t enough, then I sigh, and have to express by dancing - it becomes a performance.

Part 1

#cdramas#jdramas#kdramas#eastern cinema#acting#theatricality#asian cinema#east asian cinema#chinese culture#the untamed#word of honor

48 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sun Wukong at Beijing Opera - Journey to the west

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just thinking about fandom

Watching Chinese dramas is giving me another identity crisis. I’m too goddamned old to have more.

I’m American. I am so American that it’s 24F/-2C outside and I’m inside drinking iced water, and half my cup is ice.

I’m Chinese in descent, and have described myself as diaspora of Chinese diaspora. It’s been 2 or more generations since anyone in my family has lived on the mainland, depending on which side you’re looking at. No one from my generation speaks Chinese, and we don’t do all the festivals.

My SO is an American of New England descent, which is the best way I can sum it up. Who knows what’s all in there!

I am, as per usual, watching Shan he ling as soon as subs come out. My SO is often looking over my shoulder as I watch SHL or CQL, and often comments about how the flying and fight sequences are silly-looking to him.

It bothered me so much. It’s the not first time he’s said stuff like this, but I used to agree when I watched stuff like Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon or Hero and I couldn’t figure out why it bugged me NOW.

We talked about it, and this is why.

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon was based in some history and had fantasy elements, which I didn’t enjoy mixing.

But the stuff I’m watching now is wuxia. It’s fantasy.

Specifically, SO expressed incredulity about people flying everywhere, and I tried to explain that these people are supposed to be a bit superhuman. That they’ve refined themselves in this aspect.

What I think hammered it home was me realizing that I didn’t have a problem with it because I grew up with Chinese stuff.

I watched Beijing operas with Popo. I’m used to fights looking choreographed like they are in wuxia movies. The movements, the gestures, etc. I have so much nostalgia when I watch these wuxia shows because they remind me of watching stuff with my popo and her explaining to me what all the movements meant.

I also watched a lot of subtitled Chinese cartoons. Monkey King, obviously! And Sun Wukong flies around on a cloud. Nezha is on fire wheels! All the heavenly beings were show as flying with clouds.

It boils down to this: I’m used to seeing Chinese legends, myths, and fantasy. I’m also used to Western legends, myths, and fantasy.

SO only used to more Western things and thinks it looks odd. But I’m used to both, and I think it looks wonderful.

And we get it now. I don’t question why or how angels or fairies fly, right? So, he shouldn’t question why the martial artists in wuxia fly.

Just, please. Let me enjoy my shit.

(I’m not mad at him anymore. We’ve hammered it all out and we both get it now. I couldn’t explain to him why his incredulity was pissing me off, or why I just accept wuxia actions and fantasy til we talked it out)

#somesillypig talks to herself#fandom#east and west collides in my life#shan he ling#please leave me alone and let me enjoy myself#CQL

1 note

·

View note

Note

Hello! I was watching the Beijing Opera's Havoc in Heaven, and while I was admiring the beautiful stage makeup, I noticed that very distinct symbol on the Monkey King's forehead that looks like a swirly sunburst.

I was wondering if that symbol has any particular meaning, or if it's simply an aesthetic symbol that has come to be associated with the Monkey King through his opera makeup? I thought it might be neat to integrate it into my own design for Sun Wukong, but I'd rather not do so with a symbol I don't know the meaning and context of. I figured you'd be the best person to ask!

Chinese opera makeup is a big blind spot in my knowledge, so please take the following info as more of a suggestion than a fact.

A cursory search shows that some online sources refer to the flaming orb as a Fozhu (佛珠, "Buddha Jewel") and Shelizi (舍利子) or Sheli zhu (舍利珠, "Śarīra"). I'm assuming that Fozhu is a variation of the latter two.

These pearl-like beads figure among the bodily relics left over from the historical Buddha’s cremation (fig. 1). Strong (2004) explains:

[They are the result] of a process of metamorphosis brought on not only by the fire of cremation but also by the perfections of the saint (in this case the Buddha) whose body they represent (p. 12).

I also imagine that there is a connection to the Ruyi baozhu (Ch: 如意寶珠, “as-you-will treasure jewel”; Sk: Cintāmaṇi, “wish-fulfilling jewel”). Also known as “Dragon jewels” (longzhu, 龍珠), these luminous orbs are commonly held by Bodhisattvas in Buddhist art (fig. 2), thereby signifying their ability to grant any wish that a believer desires (Buswell & Lopez, 2014, p. 193).

It wouldn't surprise me if Wukong was depicted with a holy, wish-granting treasure due to his great power and association with Buddhism.

Sources:

Buswell, R. E., & Lopez, D. S. (2014). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Strong, J. S. (2004). Relics of the Buddha. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

#Sun Wukong#Monkey King#Journey to the West#JTTW#Chinese opera#Chinese opera makeup#Opera makeup#Buddhism#Lego Monkie Kid#LMK

102 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I've recently seen a lot of discussion that seems to be surrounding JttW, particularly on your blog. While I've only read the (translated) original work, it seems that it would be worth looking into some different adaptations. I'm not sure how knowledgeable you are about what to look into, but I'd love to hear any suggestions you may have about where to start, or even some of the better remakes, etc.

Oh hi lordofthegauntlets!! Sure thing, Journey to the West is one my fav shows that’s been made and remade over and over but I’ll never get sick of it.

The classic cartoons are a good place to start cos they’re just so choice. 1964 Havoc in Heaven (or mandarin Uproar in Heaven with eng subtitle) focuses only on Sun Wukong with that iconic red-painted face and high pitched voice, all done to popping beijing opera tunes. Despite being so old, it holds up very well and is so rewatchable. It starts with Wukong already trained in magic and the Monkey King of Flower Fruit Mountain. He goes on an adventure that ends with him getting spurned and singlehandedly trashing heaven, then going home to be beloved by monkeys everywhere. 11/10.

1999 JttW, since I grew up watching this one, is my personal Definitive Version with 54 eps. The animation is more modern (but still from 1999 lol), it’s a full, mostly faithful adaption. Zhu Bajie (Pigsy), Sha Wujing (Sandy) and Tang Sanzang (Tripitaka) and Monkey go to the west while protecting master from demons who want to eat him. Sun Wukong in basically the coolest, smartest, cutest demon ever here and the opening and ending songs are BANGERS. I love it, though it might not be for everyone cos the animation does get a bit wonky.

Here it is in full in mandarin with eng subtitle (but gotta turn the subtitle on). Be aware the first eight eps about the Havoc in Heaven has a different art style than the rest of the story where they journey west. Just because.

Here it is in a not great english dub starting at the beginning of the journey west, but sadly it skips past the Havoc in Heaven (and it’s cut weird, and it sucked out all the dramatic chinese filial piety beats™ lol).

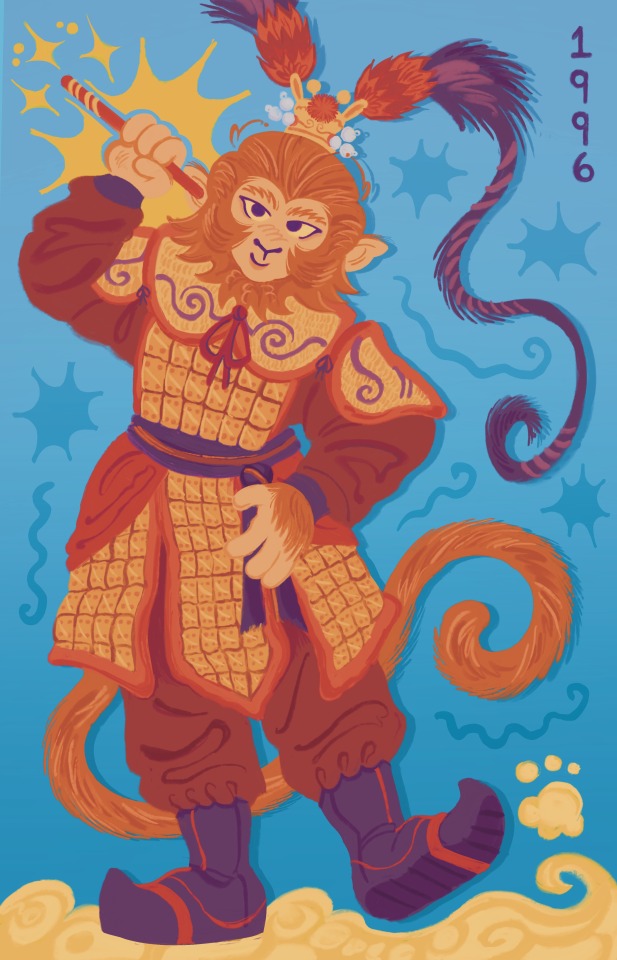

1996 JttW aka Hong Kong JttW aka the Definitive JttW for Cantonese speakers. It’s a live action series subbed in english on kissasian. This one flows really good and has a way of storytelling that’s really easy to follow. Sun Wukong does some sick flips and looks handsome, Bajie is lovelorn, Wujing is mentally impaired in this version but still a good bro, Tripitaka is compassionate but stern. It’s a less faithful adaption because of storyline changes, but it really doesn’t matter at all because it 100% captures the spirit of JttW! The journey west happens around 7 eps in, after the Havoc in Heaven arc.

Saiyuki is Japanese manga where the writer decided that the pilgrims needed to be Hot™ and Angsty™ bishounen boys with tragic backstories on a road trip with their pet dragon that turns into a jeep. And somehow this works Great. Tripitaka is Genjo Sanzo, a cynical gun-toting monk (this has guns and shit, it’s hardcore), Sun Wukong is Son Goku, an innocent teenage demon wearing a diadem that seals his awesome demonic powers, Bajie is Hakkai who is kind and intellectual, Wujing is Gojyo, an alcoholic and womaniser. (Yes Bajie and Wujing’s personalities are swapped in this version.) Together they will stop the demons from destroying the world. The art gets better as you go on and there are a few sequels and a tragic prequel (but read the original one first to get that full punch in the gut). If you need some of that good, buddhist angst, this is it.

2015 Monkey King Hero is Back is a recent animated movie that’s amazing and a lot of people swooned over Sun Wukong (a monkey) in this version who feels older, is more mature and is slightly beaten down by life (aka: Mountain to the back for 500 years). It’s essentially a JttW de-aged AU where Tripitaka is like an eight year old boy and….Wukong has to be The Adult. This is the first version ever that really uses Wukong’s monkey physicality to his advantage in fight scenes. I love it heaps and I’m still waiting for the sequel.

1986 JttW (eng sub) is usually considered the definitive adaption for mainland China all thanks to its really iconic Sun Wukong and it being the first long-running Chinese JttW adaption. It’s quite faithful to the book. But I left it last on the list cos it’s quite dated now and to someone who has never seen it before: it’s weird as hell. (Partly because live action just forces you to realise how absolutely nutty this story is.) Sun Wukong genuinely looks and acts like a monkey here - even more so than the cartoon versions!

And those are my top picks

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quick lineart practice of a Peking opera Sun Wukong. I love how detailed the outfits are.

#sun wukong#monkey king#journey to the west#jttw#xiyouji#peking opera#beijing opera#tbh the peking operas have ome of the sun wukongs#who seem to have the most fun with what they're doing#lineart#shark's sketches

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Beijing Opera Mask Chinese style handicrafts-Beijing opera dolls(Sun WuKong)-TV cabinet decorations/ ornaments/ baby gifts

0 notes

Text

While there's unfortunately no English subtitles, you can watch a Peking opera version of Havoc in Heaven free on youtube here:

Between the acrobatics, incredible costumes and makeup, and clear fun that the actors are having in their roles, it's definitely worth a watch!

#peking opera#beijing opera#journey to the west#jttw#xiyouji#havoc in heaven#sun wukong#monkey king#man#it's genuinely so fun to see a version of sun wukong#who's a silly and playful mary sue#also still find it pretty funny that when it comes to chinese retellings of the og classic#there seems to be a number of them that are just 'first half of xiyouji except the monkey king havoced in heaven & got away with it'#mt. huaguoshan troop

29 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi!

A lot of the time in pictures of the Monkey King, he has a sort of hat with two feathers(?) coming off the top of it. Are they feathers? What is this hat or hairstyle called, and what is the significance of it, do you know?

Thank you

The novel calls Sun Wukong's hat a "purple gold cap with phoenix feathers” (fengchi zijin guan, 鳳翅紫金冠). [1] This kind of head gear is most commonly associated with young heroes in Chinese opera, and it's generally portrayed as a helmet with lingzi (翎子) feathers. According to Bonds (2008):

[F]eather movements enlarge the gestures and emotions of the wearer. For example, rotating the head in circles…expands a sense of anger. Shaking the head back and forth quickly…adds to extreme frustration. Biting crossed feathers in the mouth heightens the appearance of aggressive feelings (p. 44).

But this kind of feathered headgear was once a kind of military regalia. You can see examples from this detail of The Emperor’s Return to the Capital (Rubitu, 入蹕圖), a painting from the 16th-century:

Knowing the above explains why it really, really annoys me to see drawings of the Monkey King with feathers attached to his golden headband or sticking out the top of his head like insect antennae.

That's why I wrote this article about what Sun Wukong looks like:

Note:

1) Yu (Wu & Yu, 2012) translates this as "a cap with erect phoenix plumes, made of red gold" (vol. 1, p. 137).

Sources:

Bonds, A. B. (2008). Beijing Opera Costumes: The Visual Communication of Character and Culture. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Wu, C., & Yu, A. C. (2012). The Journey to the West (Vols. 1-4). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

26 notes

·

View notes