#brice parain

Text

Ce qu’on peut demander à un livre aujourd’hui, c’est de nous rendre un peu moins méchants. Pas plus artistes, ou intelligents, ou lucides, les bibliothèques sont pleines. Et la vie donc ! Moins méchants, donc moins naïfs quant aux sortilèges, car l’homme ne sait pas être méchant. Comme il ne sait pas mentir. Il n’y arrive pas. (Si on pouvait mentir, personne ne s’en apercevrait, pas même le menteur. Le mensonge est d’essence voluptueuse. Comme l’ironie, qui en est la forme dégradée. Puis on peut aussi penser que toute vérité passe par le mensonge, qui devient biais. Mensonge spécial, qui fait un peu mal, parce que les hommes sont mensonges les uns pour les autres. Comme dit Parain, la guerre tue le mensonge, comme le microbe tue la maladie.)

Georges Perros, « Avec Brice Parain », in Papiers collés II, Éditions Gallimard, 1973

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

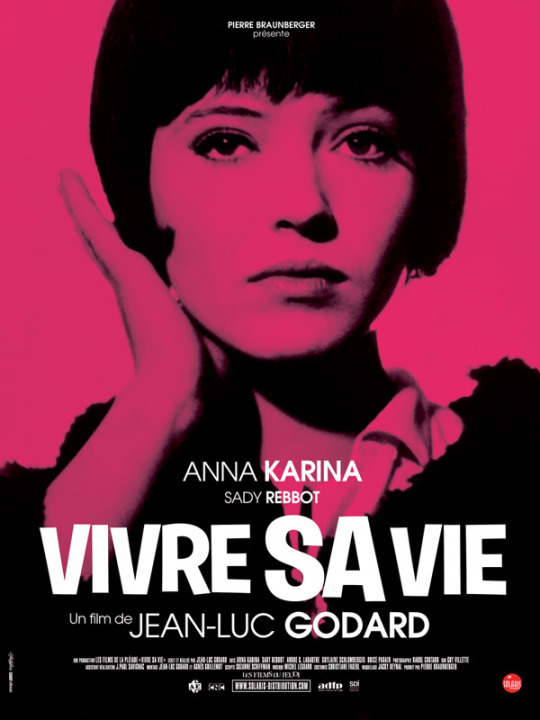

Anna Karina in Vivre Sa Vie (Jean-Luc Godard, 1962)

Cast: Anna Karina, Sady Rebbot, André S. Labarthe, Guylaine Schlumberger, Gérard Hoffman, Monique Messine. Paul Pavel, Dimitri Dineff, Peter Kassovitz, Eric Schlumberger, Brice Parain. Screenplay: Jean-Luc Godard. Cinematography: Raoul Coutard. Film editing: Jean-Luc Godard, Agnès Guillemot. Music: Michel Legrand.

The essential tension of Vivre Sa Vie comes from Jean-Luc Godard's dry intellectual detachment and self-conscious filmmaking set against his exquisitely passionate involvement with Anna Karina. It shows itself at the very beginning, when Godard gives us almost a mug shot treatment of Karina's face -- frontal, right profile, left profile -- and then follows with an extended scene that features only the back of her head. And it continues through to the end in which Edgar Allan Poe's story about an artist who sucks the life out of his beloved by painting her portrait foreshadows the death of Karina's character, Nana. On one level, the film posits art as the enemy of life, while on the other, art becomes a source of life. In the latter case, I'm thinking of the celebrated scene in which Nana is brought to tears by watching Renée Falconetti in The Passion of Joan of Arc (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1928). It can be argued that Nana identifies with Joan as a fellow martyr: Joan to her faith in God, Nana to her faith in herself -- viz., the speech in which she claims "responsibility" for everything she does. Vivre Sa Vie is full of such intellectual puzzles, including the extended conversation between Nana and the philosopher Brice Parain. But it's Karina's performance that lifts the film out of the thicket of mid-century existentialism that it threatens to become ensnared by. She makes Nana one of the essential characters not just of the French New Wave but of the entire history of movies.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vivre Sa Vie (1962)

#vivre sa vie#jean-luc godard#brice parain#anna karina#movies#film#quotes#love#long post#neil young - heart of gold#1962

664 notes

·

View notes

Photo

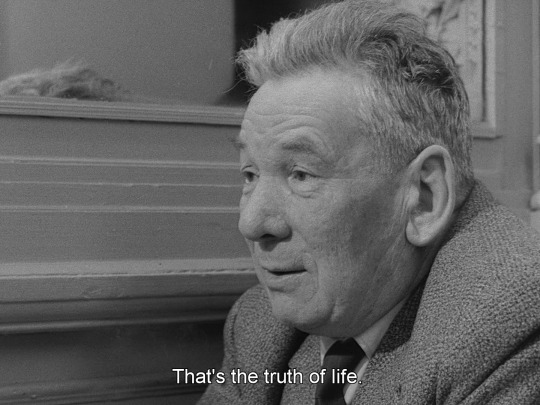

The conversation, Brice Parain / My Life to Live | Jean-Luc Godard, 1962 >

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vivre Sa Vie (1962)

#vivre sa vie#anna karina#jean luc godard#andre s labarthe#sady rebbot#guylaine schlumberger#brice parain#paul pavel#french cinema#french new wave#nouvelle vague#la nouvelle vague#film en douze tableaux

11 notes

·

View notes

Quote

A great yet forgotten philosopher of the twentieth century, Brice Parain, who was above all a strange communist and a strange Christian, wrote in the ’40s that the first monastic order of the contemporary age was born with the Soviets in Russia, that it was precisely to communism that the contemplative dimension of ‘silence’ belonged, a militant silence awaiting the Word.

Mario Tronti and Marcello Tarí, Xeniteia: Contemplation and Combat

11 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Vivre Sa Vie (Tablo On Bir: Place de Chatelet - Yabancı - Akılsız Filozof Nana)

– Bakmamın bir sakıncası var mı?

+ Hayır.

– Sıkılmış gibisiniz.

+ Hayır, iyiyim.

– Ne yapıyorsunuz?

+ Okuyorum.

– Bana bir içki ısmarlar mısınız?

+ Elbette.

– Buraya sık gelir misiniz?

+ Bazen, geçerken uğrarım.

– Neden okuyorsunuz?

+ Benim işim bu.

– İlginç. Birdenbire söyleyeceklerimi unuttum; bu bana çok sık olur. Ne söylemek istediğimi bilirim. Neden söylemek istediğimi bilirim. Ama konuşma zamanı geldiğinde, konuşamam.

+ Bu herkesin başına gelir. ‘Üç Silahşörler’i hiç okudun mu?

– Hayır. Ama filmini gördüm. Neden?

+ Çünkü, orada bir Porthos vardır. Aslında ‘Yirmi Yıl Sonra’dan bahsediyorum. Porthos, uzun boylu, güçlü, biraz da aptal biridir. Hayatı boyunca hiçbir şeyi düşünmemiştir. Bir mahzene orayı havaya uçurmak için bomba yerleştirmesi gerekmektedir. Bunu yapar. Bombayı yerleştirir, fitili ateşler. Sonra da elbette koşarak uzaklaşır. Ama o an, birden düşünmeye başlar. Koşarken adımlar birbirini bu kadar seri bir şekilde nasıl takip etmektedir? Belki bunu daha ��nce sen de düşünmüşsündür. Bu düşünce yüzünden donar kalır. Hareket edemez, ilerleyemez. Bomba patlar ve mahzen üzerine çöker. İlk etapta güçlü omuzlarıyla direnmeye çalışsa da, bir ya da iki gün içinde, ezilerek hayatını kaybeder. Düşünmeye başladığı ilk an onun ölümünün sebebi olmuştur.

– Bana bu hikayeyi neden anlattınız?

+ Nedeni yok, sadece konuşma olsun diye.

– Neden insanlar sürekli konuşmak zorunda? Belki de bu kadar çok konuşmamalı, hayatı sessizce yaşamalıyız. Ne kadar çok konuşursak, kelimeler de anlamlarını o kadar yitiriyor.

+ Belki. Ama bu mümkün mü?

– Bilmiyorum.

+ Bence konuşmadan yaşayamazdık.

– Ben konuşmadan yaşamak isterdim.

+ Evet, güzel olurdu, değil mi? İnsanların birbirlerini daha çok sevmeleri gibi. Ama maalesef mümkün değil.

– Ama neden? Sözcükler sadece insanların düşüncelerini ifade etmeli. Bize ihanet etmemeli.

+ Doğru ama biz de onlara ihanet ediyoruz. İnsan kendini ifade etmeliydi. Ve o bunu, yazarak yaptı. Düşün, Plato gibi biri hâlâ anlaşılıyor, anlaşılabiliyor. O, Eski Yunan’da yaşamıştı, 2500 yıl önce. Şu an kimse o dili bilmiyor, en azından tam olarak. Buna rağmen, hâlâ bizlere ulaşıyor. İşte bu yüzden kendimizi ifade ediyoruz. Ve etmek zorundayız.

– Neden? Birbirimizi anlamak için mi?

+ Düşünmek zorundayız ve düşünmek için de sözcüklere ihtiyacımız var. Çünkü düşünmenin başka bir yolu yok. İletişim kurabilmek için konuşmalıyız; hayatın gereklerinden biri de bu.

– Evet ama bu çok zor. Bence hayat kolay olmalı. Sizin ‘Üç Silahşörler’ konuşmanız iyi bir hikaye olabilir. Ama korkunçtu.

+ Evet ama bir işaret noktası vardı. Bence, insan ancak bir süre yaşamdan feragat ettiği zaman konuşmayı öğrenir. Bedel budur.

– Yani konuşmak ölümcül müdür?

+ Konuşmak neredeyse bir yeniden doğuş demektir. Bir anlamda, yaşamın diğer boyutudur. Yani bir insan konuşabilmek için, yaşamının konuşma olmayan bölümünden geçiş yapmalıdır. Söylemek istediğim şeyi net olarak ifade edemiyor olabilirim ama… İnsanı, düzgün bir şekilde konuşmaktan alıkoyan şey, yaşamdaki bu ikilemin farkında olmayışından kaynaklanmaktadır. Ama insan günlük yaşamını sürdüremez.

– Bilemiyorum, bu…

+ Ayrımla! Dengeyi kendimiz kurarız. Sessizlikten, sözcüklere geçişimizin sebebi de budur. Bu ikilemin arasında gider geliriz çünkü hayatın devinimi bunu gerektirir. İnsan bu şekilde, günlük yaşamdan daha üstün bir yaşama yükselir: Düşünce yaşamına! Ama işte bu yaşam da, insana, günlük yaşamından tamamı ile sıyrılmasını şart koşar.

– O halde, düşünmek ve konuşmak aynı şey midir?

+ Öyle, öyle. Bu konuda Plato’nun şöyle bir sözü vardır: ‘Hiç kimse düşünceyi, onu ifade eden sözcüklerden ayıramaz.’ Düşüncenin zorlayıcı şartı, onun ancak sözcükler vasıtasıyla kavranmasıdır.

– Peki insan, yalan riskini de üstlenmeli midir?

+ Yalanlar da maceramızın bir parçasıdır. Hatalar ve yalanlar birbirlerine benzer. Tabii burada sıradan yalanlardan bahsetmiyorum. Birine gideceğine dair söz verirsin; ama canın istemez ve gitmezsin. Görüyorsun ya, bunlar basit şeyler. Ama incelikli bir yalan hatadan biraz daha farklıdır. İnsan bazen düşünür ama bir türlü doğru sözcüğü bulamaz. Bazen ne söyleyeceğini bilemeyişinin sebebi budur. Doğru sözcüğü bulamamaktan korkarsın. Tek açıklaması bu.

– İnsan, doğru sözcüğü bulduğundan nasıl emin olabilir?

+ Çalışması gerekir. Gayret etmelidir. Kişi, kendini doğru bir şekilde ifade edebilmelidir. Söylenmesi gerekeni söylemeli, yapılması gerekeni yapmalıdır; incitmeden, zarar vermeden. Her insan doğruyu bulmaya çalışmalı.

– Biri bana şöyle demişti: ‘Her şeyde bir doğru vardır, hatalarda bile.’

+ Bu doğru. Fransa 17.yüzyılda bu gerçeği göremedi. Onlar, insanların hatalardan kaçınabileceklerini düşündüler. Ve dahası, insanların doğru yolu kolayca bulabileceklerini sandılar. Bu mümkün değildir. Buna karşılık, Kant, Hegel ve Alman Felsefesi ise bizlere, doğruya ulaşmanın tek yolunun hatalardan geçtiğini gösterdi.

– Aşk hakkında ne düşünüyorsunuz?

+ Onun da üstesinden gelinmeli. Leibnitz, hayattaki anlamlı rastlantılara dikkat çekti. Ne de olsa, hayat kimi zaman tesadüfi, kimi zamansa zaruri gerçeklerin bir bileşkesidir. Alman felsefesi ise bize şunu gösterdi: Hayatta her insan hatalarıyla yaşar. Önemli olan bunlarla baş edebilmektir.

– Aşkın, hayatın tek gerçeği olması gerekmiyor mu?

+ Bunun için, aşkın hep aynı gerçeği işaret etmesi gerekir.

-Bu güne kadar hiç aşık olduğu şeyin ne olduğunu bilen birine rastladın mı?

+ Hayır. Yirmili yaşlarında bunu bilemezsin. Yaptığın tek şey, keyfi seçimlerde bulunmaktır. ‘Seviyorum’ kelimesi çoğu zaman fütursuzca sarf edilir. Neyi sevdiğinden emin olmak için ihtiyacın olan şey ise, olgunluktur. Doğruyu aramak! İşte yaşamın gerçeği budur. Ve aşk eğer gerçekse, ancak o zaman bir çözüm olur.

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Anna Karina et Brice Parain dans "Vivre sa Vie" de Jean-Luc Godard en douze tableaux (1962), mars 2022.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Anna Karina & Brice Parain in Jean-Luc Godard’s “Vivre sa vie”

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sans outrance, sans excès, il s’ennuie un peu, l’homme. Et comme il a un grain d’innocence dans la peau, il y va bravement. Seulement il n’y a pas de miracles. L’homme est toujours muni de ses fautes. Celles qu’il connaît bien. Qu’il est seul à connaître. Je veux dire que l’homme approuve la mort, qui est scandaleusement, la justice. Tout homme sait très bien qu’il va mourir un jour, que ce ne serait pas bien, pas juste, s’il restait là, ayant péché. Certains saints savent cela, qui avancent un peu l’horloge, à petits coups de pompe funèbre. Ils ont hâte de ressusciter. Il y a de cela chez Parain. Seulement, comme il est tout de même un homme du XXe siècle, il aimerait bien ressusciter avant sa mort. Ne pas attendre les plombs funéraires pour savoir. Il ne croit pas à l’intuition, il n’est pas superstitieux, mais il sent bien qu’il n’est pas tout d’une pièce, avec ce lourd héritage dans le crâne. Il a le sens de la propreté, et s’avoue malicieusement vaincu, encoléré, outré, de voir écrit ceci, et vécu cela. Pas sorti de l’auberge.

Georges Perros, « Avec Brice Parain », in Papiers collés II, Éditions Gallimard, 1973

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Letter #6

6 - ALBERT CAMUS to MARIA CASARES

Saturday 4 pm in the afternoon (1st july 1944)

Ma petite Maria,

The trip has been good and without troubles. Left at 7:20 in the morning we drove till 9 am, then walked seven kilometers to go by a marshalling yard that was bombed the day before ; at 11 o’clock, we took another train till noon. We waited two hours at Meaux waiting for them to give us another train. Forty five minutes after, new change of train and at 5 pm, we arrived. I was exhausted like a black dog, but glad to be finished with it. They have offered me a house to which a wing had been bombed in 1940; but the rest was habitable. But it’s covered in dust and I’ll need 48 hours to turn this decent with the help of a brave women from the country.

Let’s go to the description. The country, it’s a small valley to which the two slopes are covered with cultures and average trees. It’s fresh here, there are water sounds and grass’ smells, cows, some beautiful children and birds’ songs. By climbing up a little, we reach plateau more cleared where we can breath better. The town : some houses and brave people. As for the house it is buried in the middle of a quite big garden full of trees and behind the last roses of summer (they are not red). It is in the shadow of the old church and the upper part of the garden is a sunlit meadow just under the flying buttresses of the church. We can take sunbath there. I am settling in a bedroom and an office on the first floor. When it will be done, I will describe it to you.

I think that Michel [Gallimard] could move with me at least. Pierre and Janine will without doubt be sleeping elsewhere. I wait impatiently their arrival to decide all of that and mostly because I hope they will give news about you.

I write you all of this as clearly as I can because I think what you want first is precise information. But my thinking is very different : since thursday night it is with you that I live. I felt like I had badly left you and this separation, in the middle of so much uncertainties, under a sky so full of dangers, is difficult for me to bear. My hope is that you will come. If you can do it by car, do it, it will be easier. Or else, you will have to do that very long trip I did. There’s the bike too and there I could come to you. Don’t forget your promise, my darling, I live for it at the moment. I believe I could find peace in this country. With some trees, the wind, a river, I could redo that interior silent I lost so long ago. But this isn’t possible if I have to bear your absence and run after your image and its souvenir. I don’t have the intention to play the desperate at all, nor to make myself go. Now on from Monday, I will put myself to work and I will work, that is certain. But I want you to help me and to come -that you come above all ! You and me we met here and loved in the fever, the impatience or the danger. I don’t regret anything and the days I just lived seemed to me sufficient to justify a life. But there is another way to love, a fullness more secret and more harmonious, which is not less beautiful and which I know that we will be capable of too. It is here where we will find the time. Don’t forget this, ma petite Maria and make sure that we still have a chance for our love.

In a few hours you will play. Today and tomorrow my thought will be with you. I will wait that moment when you sit down while saying that this is marvelous, I will wait for the third act with that scream I loved so much. Oh ! my darling, how hard it is to be far from what we love. I am deprived from your face and there is nothing else in the world I cherished more.

Write to me a lot and often, don’t leave me alone. I will wait as long as I have to, I feel an infinite patient in everything that concerns you. But at the same time I have an impatience in the blood that hurts me, a will to burn everything and to devore everything, it is my love for you. Goodbye, small victory. Stay close to me in thought and come, come quick, I beg of you. I kiss you with all my passion.

You can write as agreed at Mme Parain, in Verdelot, Seine-et-Marne.

Michel*

*Feeling threatened because of his clandestins activities as the director of the newspaper Combat, Albert Camus has to leave Paris to take shelter. He joins on a bicycle and on train the house of his friend the philosophe Brice Parain, head of the editorial secretariat of Gaston Gallimard, in Verdelot (Seine-et-marne), in the company of two nephews of Gaston Gallimard, Pierre (son of Jacques) and Michel (son of Raymond), and the wife of the first, Janine (born Jeanne Thomesset) -who will go on to marry in a second marriage, in october 1946, Michel. Albert Camus will now sign his letter with the name Michel.

53 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

0 notes

Photo

The conversation, Brice Parain / My Life to Live | Jean-Luc Godard, 1962 >

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Classical discontinuity and alienation in Vivre sa Vie

‘

In Vivre sa vie I have attempted to film a mind in action, the interior of someone seen from outside’ – Jean Luc Godard

As John Belton notes, “Classical Hollywood style becomes the means by which narratives are realized; it provides the formal system that enables them to be told. They draw attention to, underline, and point out what it is that the audience needs to see or hear in order to read or understand the scene” (1994, 88). Thus, style becomes a tool entirely at the dispense of the narrative. While Hollywood is concerned with the subordination of cinematography, editing, and mise en scene elements to achieve uniformity and believability in the action being communicated, Godard does the opposite in Vivre sa vie (1962). For example, during the café conversation between Nana and Raoul in episode 7, Hollywood norms dictate the deployment of a shot/reverse shot to help the audience follow the conversation. However, this only features momentarily, and other classical techniques such as the eye line and 180 degrees rules are abandoned altogether. In place, we see glimpses of Nana face behind Raoul’s as the two converse and the camera pans from left to right across the room. His looming specter-like figure obscuring Nana’s, making the viewer stretch and crane for an unobstructed view of her that is not there.

The influence of Bertolt Brecht is abundantly apparent in Vivre sa vie. As a playwright, Brecht developed counter techniques against the emotional manipulation used by fascist regimes within propaganda film, drawing parallels with the techniques and styles of the Classical Hollywood zeitgeist. These include deliberate fragmentation and episodic structure to break up the flow of the narrative, challenging the audience to be critical and active spectators. Consequently, Godard segments the film into 12 tableaus or episodes, ordered chronologically from 1 to 12 and detailing the main events during the episode in the episode title card. Between these episodes, significant spatial and temporal gaps are present, with the viewer not told exactly how much time has passed. The effect of this irregular structure and the discontinuity between episodes, with distinct variations in mood and tone, is to reduce the notion of cause and effect and open avenues for ambiguity and interpretation. For example, there is no lingering close-up shot of an important object like a key, that becomes central to the plot later. When each episode finishes, they transition onto the next through a simple fade to black, leaving noticeable aural and pictorial vacuums between the episodes where the audience is left to wonder. The discontinuity introduced by this tableau structure is heightened by Michel Legrand’s score. Chopped and spliced in no discernible order, it appears throughout the film. Less like a soundtrack and more like an operatic leitmotif, which in conjunction with the episodic discontinuity furthers the stop/start rhythm of the film, eschewing notions of lineal storytelling found in Classical Hollywood cinema.

So, if the goal of classical Hollywood cinema is to absorb the spectator into the narrative, Vivre sa Vies’ is to alienate. Godard begins doing so from the opening passage that follows the credit sequence, during the establishing scene of Nana and her estranged husband Paul in episode one. We hear them speak but we do not see their faces, their reflection barely visible on the glass behind the counter of the café. During the entire conversation, Nana and Paul are filmed separately from the back, with no cross-cutting between the two. Such separation of the aural from the visual occurs multiple times across the film. In episode 6 where Nana’s head occupies most of the frame as she talks to Yvette. In episode 9, where the profession of sex work is explained to Nana in procedural detail through a montage and in the penultimate episode, where Nana is seen speaking to her new lover. The dislocating effect is furthered in this scene as the spoken conversation is alternated with the subtitled version, suggesting all is not well, calling into question the very reality of what is occurring altogether.

Godard’s subversion of classical Hollywood conventions is clear to see from the opening credits where Nana is first introduced. Instead of through the classic three-point lighting system, she is (partially) revealed through several brooding shots. First, an extremely poorly lit, close up shot of her side profile that is followed by a close up straight on, then a return back to her side profile with just enough light to reveal the silhouette of her features. During the second close up of Nana’s full face, she looks back at the camera hesitantly, twitching and biting her lips, aware of the cameras invasive gaze, challenging “Hollywood’s pride in concealed artistry” (Bordwell 1985: 25). This awareness and erasure of the fourth wall, a stable tenant of classic Hollywood practice, is not isolated to the credit sequence. Nana meets the gaze of the camera again in the interrogation scene in episode four, but even more directly this time, and with a palpable sense of discomfort. In doing so, she removes the security of the cinematic one-way mirror and posits uncomfortable questions regarding the role of the spectator as an active and ravenous consumer of Nana, her life, and her body.

Classical continuity editing is also subverted in episode 7 when Nana and Yvette are in the café. Instead of cutting to the pair sat down, the camera pans from right to left, canvassing the non-diegetic bodies inside and outside the café while their conversation continues in the background. Later near the end of the scene, Godard uses a POV pan shot from Nana’s eyes which again tracks the café landscape and the people within it. Given that Nana and Yvette are the primary causal agents in the screen, this return to the same camera movement and subjects further unsettles classic continuity editing. The Mise en scene also marks a departure from traditional Hollywood filmmaking which is identifiable by its deliberateness, studio sets, and pre-planning. Vivre sa Vie is filmed almost entirely in the streets and cafes of Paris (the interrogation scene in episode 4 was shot in the studio office), with the presence of non-actors that often acknowledge the intrusive presence of the camera. As a result, the dialogue is often difficult to hear, as ambient noises and conversations duel for center stage, imbuing the film with an ambiguity that asks the viewer to assess what they see and hear critically and not as the narrative dictates.

The selective denial of Nana’s face to the camera establishes itself as a recurrent motif in the film. It is evident in the credit sequence, during her argument with Paul in episode 1, in episode 2, where she is hidden by a column while she works in the record store and once again in episode 8 when Raoul takes her on as a prostitute in the café. Coupled with the rheumy, nervous looks Nana darts back at the camera regularly, it presents an unsettling question about the devouring gaze of the camera and the viewer’s role as her secondary consumer. Godard teases this idea further in the last episode, where he inserts himself into the scene to read an excerpt from Edgar Allen Poe’s Oval Portrait. The story concerns a painter’s morbid obsession with capturing every aspect of his wife on canvas, which ultimately leads to her death. Given the story’s singular focus on Nana (Anna Karina), who was also Godard’s wife at the time, it provides a macabre auteurial self-awareness that is ‘emblematic’ of art cinema (Bordwell 1979). There are more examples of Godard’s self-reflexivity throughout the film - the shot of fellow New Wave pioneer François Truffaut’s ‘Jules and Jim’ screening at the theatre in the last episode, the lengthy inclusion of the real-life philosopher Brice Parain. These inclusions all serve to disjuncture the narrative in a Brechtian way by continually reminding the spectator of the artificiality of the medium and challenging them to be an active and critical viewer.

In place of heavy editing and swift cuts, Godard opts to use simple, drawn-out long takes to underline the voyeuristic nature of filmmaking. This can be seen throughout the film, from the opening scene where Nana leaves Paul, to episode 2, where the camera tracks Nana over several minutes working in the record store. While classical Hollywood conventions focus on verisimilitude to transport the viewer into the reality being conveyed in the narrative, through, for example, costume design, special effects, or period-specific dialect, Godard subverts this not by breaking verisimilitude, but by attuning it to the mundane, the liminal, and the inconsequential. He utilizes extensive long shots of Nana working in the record store, going over to different shelves (episode 2), speaking to Yvette (episode 6), challenging the audience to confront the reality of everyday life. Godard also draws an interesting comparison between this scene and the scene in episode 10, where the camera tracks her movement as she inquiries into different rooms in the brothel looking for other girls at her client’s request. Given Godard’s Marxist background, it is plausible that he is drawing parallels between both forms of labor, as under capitalism everything of value is commodified. This labor/capital relation is also explored during the montage in episode 8, where wage, taxation and hours of work are discussed as well as during the letter scene, where Nana is writing down her qualifications to send to a brother owner outside the city.

Notably, the title of the film – “Vivre sa vie” translates to ‘to live one’s life’ as the verb ‘Vivre’ has neither subject nor tense, creating a title loaded with passivity and detachment. This passivity, or rather lack of personal agency, is hinted at throughout the film in relation to Nana’s character, from the parallels established in the cinema between Nana and Falconetti’s doomed Jeanne d'Arc through close-ups, to the omission of her movement through various spaces in the film. While she occupies a varied range of spaces throughout the film; hotel, café, record store, police station, theatre, the Parisian streets, she is hardly ever shown moving between these places. For instance, in episode 10, where she is seen checking different rooms across the brothel for women that are available, but only shots of her opening doors, or just arriving, are included. A similar denial of her corporeal dynamism occurs in episode 9, whereupon Nana and Raoul exiting his car, the camera quickly pans to him talking to the bartender and then Nana arrives abruptly. On the rare occasions Godard chooses to show Nana moving between spaces, she is almost always accompanied by another person (Yvette, her first client, Raoul). In episode 5, where she is alone and walking the streets of Paris looking for clients, the camera pans slowly from right to left, hinting a regressive change has occurred as Nana begins her new life as a sex worker under Raoul.

This lack of agency for Nana is symbolically captured in episode 3, where she attempts to break into her apartment to which she cannot afford the rent. There are three doors for her to get past. First the door from the street to the courtyard, which she passes through, only to retreat off-camera, and come back through again. Following this is a cut to the concierge sweeping and a high angle shot of the courtyard where we can see the door to the concierge’s office where the key is stored. Nana runs, attempting to steal the key but is stopped by the concierge. She fakes defeat and tries again, making it past her only to be stopped by the concierge’s husband who is near the third door, not even making it to the door of her apartment. Despite this, Nana claims that itis indeed her life to live, claiming “I smoke, that’s my responsibility, I am unhappy, that’s my responsibility…”. However, it is plain to the audience who are privy to a birds-eye view of the events unfolding, that she has very little choice nor chance in the events that are about to transpire.

While Nana’s demise and her lack of personal agency are clear to the viewer, it is tragically juxtaposed by her own affirmation that it is indeed “her life to live”. Through conscious cinematographic and mise en scène choices, as well as various editing processes and framing techniques, Godard encourages a conscious spectator and bring to light the artificiality of cinema. The focus on the every day and the mundane - the many café scenes and the inconsequential dialogue throughout the film capture aspects of reality typically ignored by Classical Hollywood cinema. Furthermore, the absence of a studio set, and limited use of camera variety lends the film a documentary-like quality, where each uncomfortable look returned by Nana to the camera elucidates he extractive dimension of the subject/viewer relationship being played out on-screen.

Bordwell, D. (1979) ‘The art cinema as a mode of film practice.’ Film Criticism, 4(1), 56-64.

(1985) ‘Classical Narration.’ In: Bordwell, D. & Thompson, K. (eds.) The Classical Hollywood Cinema - Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960. London: Routledge.

Belton, J. (1994). American cinema/American culture. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc.

Vivre sa vie (1962). [Film]. Jean Luc Godard. dir. France: Films de la Pléiade.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Godard bajo el peso del tiempo

Por una vez, y sin que sirviera de precedente, en España pudo verse Vivre sa vie (1962), a través de la entonces muy activista Federación Española de Cine-Clubs, con inusitadísima puntualidad, o con no mayor retraso que películas más “comerciales” y “normales”; si no me engaña la memoria, la pudimos ver por el año 1964; sólo Alphaville y Pierrot le fou se vieron con menor demora, aunque, ¡horror!, sólo dobladas. Ni siquiera recuerdo ahora cuándo se estrenó por fin Vivir su vida en pantallas comerciales, pero debía haber cumplido veinte años. Ahora, cuando hace 44 que se rodó, vuelve, y me temo que resulte mucho más rara que en su tiempo, cuando sorprendía por su novedad. Curiosamente, como el cine ha retrocedido y se ha renovado muy poco —lo que no quiere decir que no se hagan ya magníficas películas; se hacen, pero ahora no es que tarden, no llegan—, Vivre sa vie, en lugar de quedarse anticuada, envejece al resto de la cartelera, un poco como debe haber sucedido el mes pasado en el mismísimo París con Las dos huerfanitas (1921) de D. W. Griffith.

Cuando tantos se preguntan hoy —entre los que aún reflexionan sobre lo que ven— acerca de la simbiosis misteriosa del documento y la ficción, toda Vivre sa vie se basa en el paso constante de uno a otra, de lo real seleccionado a lo casi teatral, de la improvisación (aparente) a la elaboración (previa, no espectacular), de la frialdad del informe a la intimidad vertiginosa, preocupante, del retrato. Una emoción intermitente (como siempre en Godard, véanse los “episodios”, los fundidos, el tratamiento de la música) surge inopinadamente en medio de la descripción objetal y distanciada de la sordidez más gris.

Baile repentino

Un baile repentino de Anna Karina alrededor de una mesa de billar, un número cómico para ponerla de buen humor, una canción de Jean Ferrat (que el propio cantante escucha, procedente de un juke-box), la conversación en un bar con el filósofo Brice Parain, la voz de Godard que lee El retrato ovalado de Poe, la muerte brutal e inesperada de Nana, cercana en algún sentido a la de Anna Magnani en Roma, ciudad abierta, que sólo entonces comprendemos que estaba prefigurada por la escena en que se le saltan las lágrimas al contemplar a Maria Falconetti y Antonin Artaud en La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc de Dreyer.

Esta película tierna y dura, que en lugar de la modulación o el deslizamiento juega a la brusca ruptura de tono, al cambio de dirección, es una muestra sorprendente de que Godard, en lugar de mostrar y exhibir su trabajo, filmándolo o amplificándolo, lo esconde anticipándolo. Su “puesta en escena” es fundamentalmente mental, previa al rodaje, en el momento en que elige dónde va a situar la cámara, si va a dejarla quieta o a moverla, si nos va a permitir ver de frente o va a obligarnos a escrutar las imágenes, a espiar a los personajes, que por su parte —y sobre todo la heroína, Anna Karina, su mujer— tratan de esquivar nuestra mirada, mientras Godard los persigue y acosa o les permite un respiro, un poco de aire, pero sin dejar de vigilar sus rostros o sus movimientos, contemplando sus cogotes, sus espaldas, sus hombros, que también les delatan y revelan. El interrogatorio policial al que es sometida Anna Karina es un poco el modelo de esa confrontación de la que surgen las mil facetas, los mil rostros de la actriz y la mujer que fascinaba a Godard.

Misterio permanente

Y es quizá ahí donde residen el misterio y la originalidad permanentes de Vivre sa vie. Es, sin contarnos su vida, bajo el ropaje de un documental sociológico a ratos, de una “serie B” (a la que está dedicada) policíaca otros, de un melodrama o un musical en ocasiones, una película en primera persona, una reflexión moral y filosófica acerca de la realidad y la vida, acerca de la libertad y las circunstancias, acerca del cine también, en la que no se nos pide que sintamos empatía con ninguno de los personajes, sino que nos identifiquemos con el propio autor, que así dialoga y discute directamente con cada uno de los espectadores.

Sí, Vivre sa vie sigue siendo un estimulante desafío al espectador y una frontera del cine en la que sigue, tantos años después, Godard como explorador de avanzadilla, pues, al no haber sido seguido, permanece como solitario oteador, en terreno inexplorado, y ahora —desde hace cierto tiempo— no sólo hacia el futuro, sino también hacia el pasado, tratando de comprender dónde y por qué se perdió el impulso y se abandonó la búsqueda.

Miguel Marías

El Cultural, 27/07/2006

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Anna Karina dans “Vivre sa Vie” de Jean-Luc Godard en douze tableaux (1962) avec Anna Karina, Sady Rebbot, André S. Labarthe, Gérard Hoffmann, Guylaine Schlumberger et Eric Schlumberger et la participation philosophique Brice Parain, mars 2022.

1 note

·

View note