#but in political spheres i think it's way more important to be clear and accurate

Text

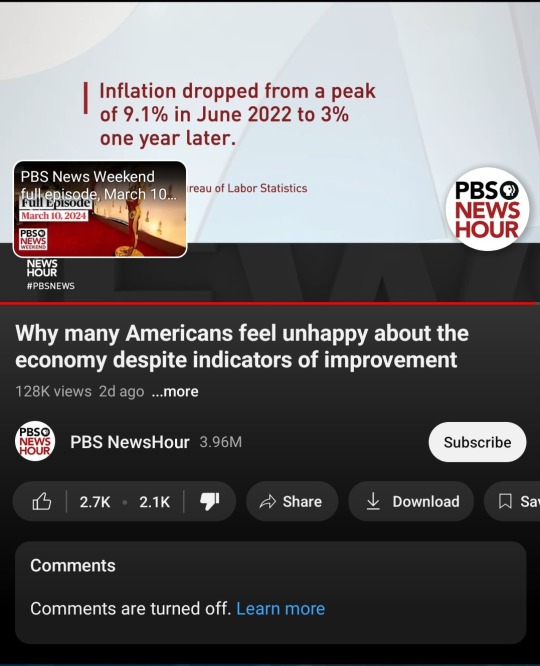

LMAO at the like to dislike ratio. I can't speak for everyone who hit dislike, but for me it was the fact that they only grazed the surface of the real problem and ultimately reduced it to something that sounds much more trivial.

Idk if this channel usually keeps comments off, it would make sense for news, but I can't help but wonder....either way, that's why I'm babbling here.

TL;DR (bc y'all already know all the concepts I'm rambling about)

They kept acting as if the economy doing well was a fact, and whether that's accurate...depends on definitions. They kept referencing statistics like low unemployment and shrinkflation being marginally less bad than before.

People don't feel good about the economy because IT'S NOT SERVING THEM WELL, FUCKASS. Working is not automatically better than not working, because the sheer volume of people who live paycheck to paycheck indicates that it's not a truly functional system (functional for the general population, that is). Living paycheck to paycheck is living in constant anxiety. That's not even touching on things like people who SHOULDN'T be working being forced to work through necessity, because disability isn't enough to live on and all that. Your metrics don't mean shit if you don't add some quality of life measures. So if you were asking them if they thought the economy was getting good grades in capitalism, sure, you'd be right to say that it is (I'm assuming based on The Statistics they keep mentioning), but most people aren't gonna think hmm, how would I rate our country if I were doing an assignment in economics class? They're gonna think what is everyone experiencing, money-wise? And we all see that this huge chunk of people are struggling in that department. You think people, especially the struggling people, are gonna assume you're asking about The Statistics? Only if they've recently heard the news that The Statistics are doing well and it stuck in their brain, or if they majored in economics or some shit. That last bit is entirely an assumption on my part and kind of a joking projection about my own memory, but more importantly, even if you make it clear you're asking about concrete metrics like unemployment, they usually only have their own experiences to formulate a guess unless they happen to be knowledgeable in economics. So why the fuck would they guess that the numbers are high if everything they see irl and on the internet is people struggling?

So yeah, unemployment numbers being low isn't much consolation to anyone who isn't rich. At best there will be individuals glad they have a job because they need one to live.

Outside of the academic/analytical sphere, the economy is fucked. They're literally correct. Seems kinda out of touch to not consider *the human experience of actually not having enough* to be an important variable, but I shouldn't be surprised.

Anyway, another aspect was called "vibeflation", which is when the economy is technically doing well but no one feels like it is, and it was tied to...you'll never guess....politics. Apparently people consistently feel more optimistic when their party is "winning". The way they framed this, imo, implied that it was this inherent human quality that was a likely cause of the dissatisfaction for many/most people. They ended off mentioning vibes again. It felt very condescending, as if the silly peasants are ruled by their emotions and don't truly understand the economy.

They mentioned people in poverty existing but given that I can't even remember what was broadly said about them, I think I'm correct in my memory that it was pretty substanceless. It was definitely brief.

I wanted to leave a comment, bc this irritated me lmao. Shame on me for thinking maybe PBS would have a little more awareness.

#i did other stuff for like 10 mins and now my brain refuses to get back into it to make sure it makes sense and inevitably add more thoughts#so hopefully this is coherent. or not seen by anybody which is likely either way#oops. im back to this post later and i definitely added more. but i can't reread it all im not strong enough#chronicles#discussion#tbh im pleasantly surprised that i wrote all this even if it's disorganized as fuck. the bupropion dosage bump is kicking in

0 notes

Text

long post about generational communication and fandom discourse LOL

as someone in my mid 20s on this site, i've lately been sort of feeling like someone watching an F1 race where I'm just kind of standing on the side of the road looking at trees and then an incredibly verbose chunk of fandom discourse filled with cryptic abbreviations and terms i've never heard whizzes past at 200 mph. and it's made me think a lot about how zoomers and younger millennials consume media, how the media itself has changed concurrent with shifts in the way people discuss and ingest games and tv shows and content creators.

it's important to note that the fandom sphere is huge and heterogeneous and discussing it as one mass with shared attitudes and content ideologies will never be completely accurate. but i do think there are some assumptions that can be made specifically about online fan spaces.

one thing that's endlessly fascinating to me is the way there's not really an online generational divide anymore, and as fandom moved online, it grew into a totally all-ages space with only dotted line divisions between groups of, for example, high schoolers vs. 35 year olds. imagine an enormous room where 12-14-yr-olds are continually entering as they make tumblr accounts and begin to engage with people about the cartoons they like, and at the other end of the room an adult will occasionally be like "see ya" and leave, but the majority of them are still hanging out and even mingling with the kids. which is maybe a creepier mental image than I meant to give; what I mean isn't that adults in fandom are necessarily predatory, but that you now have an ecosystem populated by people with vastly differing levels of maturity and very different modes/expectations of communication.

it seems like that's where a lot of misunderstandings about fandom come from: when someone criticizes fans of a children's cartoon for saying x or not decrying the bad behavior of a character, they could be talking about a preteen or they could be talking about someone with preteen kids. our expectations for the behavior of these two people is (and should be!) very different, but without universal participation in the (frankly very stupid) practice of listing all one's census data in the description of their blog, we are often missing this critical information.

the solution I'd like to see (and something that seemed to be happening outside of fandom like 15 years ago, when I was just beginning to get online) is a generational shift away from categorical judgment, where anyone who identifies as X or consumes Y media is irredeemable, the rift is too great to even attempt communication, etc. cutting off communication from a friend because of a disagreement is an extreme solution, and in general, it pays to be more tolerant of your friends than you would be about random strangers online, but maybe we can even extend well-intentioned strangers some lenience too? we also need to talk about when someone with a bad opinion who's since changed their mind is considered rehabilitated, because it feels like there are clear guidelines for shutting these people out of circles but not for welcoming them back in. but that's beyond the scope of this lol

instead, what i'm seeing are sect-based politics based around what content people find entertaining/appropriate, in the same way identity politics among queer people have been both tremendously helpful at building community and the cause of incredibly stupid, insular infighting between people who have a very obvious common enemy.

I think we have to allow our friends to have different tolerances for things that offend us. We have to accept that things that are outdated or problematic can also be beautiful and worthwhile (albeit worthy of mindful criticism). But above all, we should recognize that obsessing over petty disagreements does not make a community stronger or more pure.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Specific Critique of Our Politics

There is growing sentiment that our current political system is broken & needs fundamental change. This to me is both obvious & necessary, but we need to figure out how to navigate the problem of changing fundamental power structures. Here's what I think is the single most elegant & specific critique of both sides, hopefully in a way that provides the eventual clarity necessary to solve our shared problems together.

Both the right & left, individuals, ideologies & political parties are a mess & frankly embarrassing to participate in, hence the record turnout of this year, is still lackluster in any direct analysis. There is much broken to fix, but starting point is important.

The right needs to recognize a deep failure within its moral & psychological framing of people & events. There is a type of 'moral' double bind social dynamic I despise. 'Holier than thou' is one way to describe this double bind game. Another way to phrase it, popularized by Bret Weinstein, is the Personal Responsibility Votex. It works by framing another person such that all their possible decisions appear to be either direct moral failing, or make them powerless. In a large social dynamic this allows the deceptive public figures who use it to blind their audience to the social & moral critiques applied to them by those attempting to constrain their ruthlessness.

This is a common dynamic used by the establishment on the right against their audience, & I believe one of the social forces driving the right into wildly overblown conspiracy theorizing instead of toward the most effective & elegant criticisms of our current social system provided by conscientious objectors on the left, & 'center'. I want to call it something with an egoic sense, beyond the specific tactics used. "I don't need to pay attention to anyone's worldview & ideas except my own because anyone different from me is either weak or a hypocritical liar."

A good concrete & meaningful example is a situation which my own family is in, & a decision tree I have faced myself. I am a staunch environmentalist, although my perspective is far more nuanced than the common tropes of the popular narratives. #solarpunk & others do a good job of popularizing more generally correct ideals closer to my own.

To the point, my family owns oil properties. Oil is clearly a dysfunctional primary energy source going forward, far beyond carbon dioxide, but deeper into how the industry impacts the world in which we all live. Global politics (war & conflict over who profits from oil), finance (who oils & controls society through oil), transportation (asphalt is oil), plastics, farming (fertilizer is oil), pharmaceuticals (organic chemistry can be oil) are all fields of society deeply disturbed by the power structures of oil.

I don't want to participate in that, but I cannot sell my property. If someone else owns it they will build far more pumps & extract far more oil than I do or ever have, or plan to do. I also would be foolish & insane & counter productive to my goals in their pure form if I took a purist stance & went bankrupt via halting all pumping on my property. I would still loose everything to the ruthless oil magnates, but I would also be incapable of doing any good in the world.

Either I am a hypocrite or too weak to do anything useful or meaningful in the world. The situation is systemically broken. Only legislation that stops oil extraction allows the rational approach of my situation to result in an outcome I can accept as good. Until then my moral duty is best served by pumping oil to invest in environmental causes. Which is an absurd situation to find oneself in, but from a sane perspective there is actually no more moral or correct option available to me. I've considered all possibilities at length.

This is a double bind, that traps me in technical hypocricy as the most morally & ethically optimized stable position I can hold. All other positions make those who would harm the earth more powerful at my expense. This is not my failing, but a tragedy of the wise. Understand this, find & respect people who hold positions similar to mine out of moral duty & necessity, despite the tragic self-contribution to the very process which I find necessary & right to end.

*

The left equally has a grave error.

I find it a laughable failure of the intellectual & media elite of the left do not possess & destribute as common knowledge the game theoretic conclusions ones reaches upon an analysis of our voting system. Plurality Voting or (first past the post) #EndPluralityVoting, is an awful system of selection for solving any democratic problem. You will know it as "Choose One Candidate" on a ballot sheet. This voting method itself, as opposed to any other reason, is the specific direct reason we have a two party system. This is a certain & abject truth, that with depth, is inarguable.

The direct, most elegant & most superb alternative system is called #ApprovalVoting, & it is what you would know on a ballot as "Choose One, Or More, Candidate[s]."

Many social media polling systems have this as an option, always use it, it should be the universal voting process default.

Approval Voting has one challenge that prevents it from being common place across democratic systems, it requires a well crafted Parliamentary system to be used at the political stage above it. The two systems integrate together exceptionally well, for deep, nuanced & powerful technical reasons. Of primary import is that Approval Voting most accurately represents the true values & views of the demos, the people, at the cost of some stability & of having an electoral majority. The Parliamentary system handles greater volitity & also non-majority leadership situations better than other political systems.

This is all clear & obvious to me after analyzing political processes, but because this knowledge does not serve the self interest of collecting power, it is not the well destributed understanding of political systems that it should be.

(I will quickly note the popular alternative voting system of #RCV or ranked choice voting. This is a cludge, I support it as better than plurality voting, because anything is, but the only reason it is the voting method of choice is because it's compatible with our current very broken political system, not because it has any superior qualities to approval Voting. It's complicated and less useful. Approval Voting is superior at every angle of analysis except how easy it is to achieve in our current dysfunctional moment.)

*

The sources of dysfunction that are most are fault for neuroticizing us on whichever side, I lay foremost at the feet of these two problems in our approaches to addressing problems in the political/intellectual sphere.

It is time to start applying ourselves with astute, well rounded & careful analysis of broad human systems using the tools of Game Theory & of evolutionary process analysis, which some might know as market forces.

I could go fard deeper into more problems, ad infinitum in fact, I think & write at length on these topics elsewhere, but posting some thoughts on the dysfunctional mess that is our ongoing political moment is a necessary duty I feel is apt & appropriate here.

Thanks for reading.

Take care & keep your soul.

🌳♂️ Masculine Way of Life!🧔🥊

#Election#2020#Voting#Politics#Economics#Solar punk#environment#Environmentalist#solarpunk#Economy#Eco#cottagecore

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Effectively Initiate Positive Alliances With Appropriate Spirits Outside of Your Immediate Sphere

Today, I want to write a bit about something very useful I’ve discovered about initiating positive, tangible relationships with spirits who are (at least seemingly) outside of your immediate circle of spirit guides, for purposes of guidance and magical collaboration.

Aside from sometimes collaborating in readings with my clients’ departed loved ones, as a medium who occasionally practices “emergency magic,” up until recently, my spirit guides never let me work with any spirits who weren’t part of the circle of guides assigned to me at birth, or ones sent to me by them for a given purpose, such as helping me predict the future more accurately. This “forbidden list” included saints who are often petitioned in popular forms of practical magic, such as St. Expedite, as well as employing the magic of other practitioners (often working with other spirits) by ordering candles from them, etc. These restrictions existed, and mostly still do, for my own protection, in order to ensure my spiritual and energetic integrity. I know better than to second-guess my guides’ advice.

Luckily, once these restrictions had been established, I came to realize that any magic I had practiced before, without soliciting spiritual helpers, which would involve fairly elaborate manipulations of physical objects as energetic focal points, would pale in comparison in effectiveness to the results I would get from simply going through my channeling preparations, clearly and passionately telling my guides what I needed, and then asking for help.

Sometimes, the results would be dramatic and nearly instantaneous - and if not, my guides would be sure to inform me that results would take a while. Coming to realize just how simple effective magic could be was incredibly liberating!

However, magical work aside, I would sometimes wonder what it would be like to receive guidance or help from a spirit who held a particular cultural or emotional significance for me. Mostly, these were departed artists with whom I felt a kinship.

With the possible exception of murder investigations, etc., the conventional wisdom on evidential mediumship is that you can only successfully interact with a departed person who knew you or your client in life. So, this spring, I decided to do an experiment with an inspiring artist with whom I had a fleeting in-person encounter in life, and about whom I had been thinking about a lot during quarantine: David Bowie. The personal connection may have been tenuous, but it was there.

What I discovered turned out to be an extremely effective way to form new, rich relationships in the spirit world.

One day in May, before it felt safe to get on the subway, after 100 days of not leaving my home borough, I walked all the way from South Brooklyn to Manhattan. When I reached SoHo, I realized that I was not far from where David Bowie used to live. So, I took a little detour.

As I came up to his house, I focused my mind inward, as I would when asking a question of my spirit guides, and silently addressed him:

“Hi, David! It’s Emily, here. Remember me? I’m the teenage girl who quietly interrupted your lunch back in the summer of 1998, at French Roast on 6th Ave., to thank you for all the inspiration you had given me as a musician and artist. You were so touched, you blushed like a beet! I never forgot about it. I’ve been thinking about you a lot, lately, and could really use some inspiration and guidance from you again. We are kindred spirits! Musician to outsider musician, can you hear me? I’d love it if we could interact, and you would accept to be my guide.”

Within a couple of hours, David sent me a synchronicity in the form of the gif below, posted by my friend right around the time I made the connection. (In these cases, I don’t believe in coincidences. My guides pull off stuff like that all the time, and it isn’t limited to random internet posts.)

A similar process has subsequently helped me form several new, extremely satisfying spiritual connections, including with Frida Kahlo, whose birthday party I posted about earlier, and even a couple of saints I never thought I had a connection to before.

That is how I found out that under the right circumstances, there is some flexibility in my “collaborative restriction,” and it is sanctioned by my personal guides. However, it isn’t arbitrary.

When you wish to form a relationship with a spirit outside your immediate sphere, the key is that there needs to be an affinity, cultural, familial or even personal connection between you and what you know of this spirit. This holds true whether it is a person who was known as a prominent spiritual teacher, an artist who passed away relatively recently, or a saint or spirit whose existence has taken on a more “storied” status. (Religions of the African Diaspora such as Santería, Vodou and Espiritismo - which I have no affiliation with - affirm this in their teachings, as well.)

So, here is my technique for forming new alliances with spirits you’d like to work with.

1. Identify the spirit, and define for yourself why you wish to work with them. Look into the spirit’s history, and the various ways in which people have defined and worked with them before. Do you feel comfortable with all of the connotations of what this spirit stands for?

2. Define the connection between you. What is it that you have in common in your temperament, your likes and dislikes, your interests, your cultural connections, your life experiences, your “life missions,” and your general energy? Why and how does your energy “match” theirs? (This is super important!)

3. If the connection isn’t immediately apparent, is there a work-around? For instance, say you wanted to work with The Virgin of Guadalupe, who is a Catholic patron saint of Mexico, and particularly a protector of indigenous peoples, but you weren’t Mexican, indigenous, or even Catholic. Guadalupe is also known as “Empress of The Americas,” and is an apparition of the Virgin Mary. Mary was Jewish. In my case, I’m Jewish-American. I’m a Jewish daughter. Mary is a Jewish mother. I’m part American, and live in the USA. She’s Empress of The Americas - not just Mexico. That would be an effective approach to initiating the connection.

4. Find a way to focus your energy on forming the connection. This could be through setting up a little altar with a picture, a candle, some water and flowers, or simply meditating in a quiet place or sacred space, especially if that place is directly connected to that spirit.

5. Address the spirit with love, trust, enthusiasm and respect. In your own words, explain the connection between you, and why you wish to work with them. So, for the above example, I might say: “Dear Guadalupe, I would love to work with you and your gentle, motherly energy. You’re a Jewish mother, and I’m a Jewish daughter - that makes me your daughter! People love you in my neighborhood. You rule over the Americas. I know your presence is strong here. Would you help to bring peace and love into my home?”

6. Look for a sign of acceptance. In my case, that will usually come in the form of a synchronicity, a dream, or having them straight-up announce themselves in my channeling sessions. (Often, it will be more than one sign!)

7. Once you receive your sign of acceptance, especially if they happen to grant a request, GIVE THANKS! I love buying flowers for my spirits. It’s also great if you can thank a guide or spirit ally with charity or a good deed that benefits people or causes you know are loved by them. In the above example, I would make sure to buy the flowers for Guadalupe from the ladies in my neighborhood who are immigrants from Central America - and possibly undocumented. I might also make a contribution to charities that help detained immigrants at the border. Sometimes your allies will telepathically let you know what pleases them.

And that’s it!

You can maintain your ongoing connection to these spirits through practices such as meditation and channeling, and also doing good deeds in their name. If you only wanted to form a short-term alliance, that’s OK, too. Just be sure to thank the spirit properly for their help, and politely say your goodbyes.

As a final note, it isn’t completely clear to me whether the initial lack of connection to spirits such as these is only skin-deep. One might have past-life alliances, or other unknown connections to these spirits from the get-go. Sometimes, if you feel pulled to a particular spirit, but can’t figure out the connection, if you ask your guides, and the connection is genuine, they will explain why!

We all have “inner circle” guides assigned at birth, whom we can most easily connect with, and especially if we work in the spiritual arts such as mediumship, a whole network of “outer band” helpers in our “team,” who may prefer to remain anonymous, but help us coordinate communication with our clients’ loved ones, etc. You won’t always know immediately who is helping you “behind the scenes”!

Explore these concepts for yourself, and see what you think! ...But do choose your allies wisely, and protect yourself by keeping your energy high, joyful, compassionate, optimistic and loving, and by properly opening and closing your communication sessions. Don’t fall for impersonators! Look for tangible signs.

Any questions? Let me know in the comments!

Good luck!

Love,

Emily

#spirits#spirit guides#spirit allies#espiritismo#magic#magick#practical magic#mediumship#channeling#spiritual journey#guidance#david bowie#guadalupe#spiritual#shaman#shamanism#psychic#psychic medium#psychics of tumblr#mediums of tumbler#witches#witches of tumblr#witchcraft

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

via Politics – FiveThirtyEight

Politics has a funny way of turning arcane academic debates into something much messier. We’re living in a time when so much in the news cycle feels absurdly urgent and partisan forces are likely to pounce on any piece of empirical data they can find, either to champion it or tear it apart, depending on whether they like the result. That has major implications for many of the ways knowledge enters the public sphere — including how academics publicize their research.

That process has long been dominated by peer review, which is when academic journals put their submissions in front of a panel of researchers to vet the work before publication. But the flaws and limitations of peer review have become more apparent over the past decade or so, and researchers are increasingly publishing their work before other scientists have had a chance to critique it. That’s a shift that matters a lot to scientists, and the public stakes of the debate go way up when the research subject is the 2016 election. There’s a risk, scientists told me, that preliminary research results could end up shaping the very things that research is trying to understand.

Take, for instance, two studies that hit the press in late September. One was a survey of nonvoters in Wisconsin that seemed to show that the election could have swung President Trump’s way because of voter ID laws that kept people from the polls. The other was an analysis of junk news shared on Twitter that offered evidence of misinformation being targeted at people living in swing states in a way that implied a strategic effort. Neither had gone through peer review before receiving largely uncritical write-ups in major publications like The New York Times and The Washington Post. Both contained the sort of everyday flaws that the peer review process is designed to catch — flaws that undermined the reliability of the results.

But political scientists, and social scientists who study science as an industry, told me that the choice to publish before peer review isn’t rare — and isn’t necessarily even all that problematic. Across the sciences, it’s increasingly normal for research to appear in publicly accessible places — on research archives, Twitter and Facebook, blogs — and, from there, find its way to the media before it’s been vetted by anyone other than the people who wrote it. Political scientists disagree broadly on whether that’s a good thing, a bad thing, or a little of both.

Results that make it onto the public radar can play a big role in shaping how people think and what they believe, even if that research turns out to be wrong later.

Historically, most research hasn’t been presented to the public until after peer review. What comes out the other side is not guaranteed to be correct — in fact, individual peer-reviewed papers often turn out to be wrong. But, on aggregate, 100 studies that have been peer-reviewed are going to produce higher-quality results than 100 that haven’t been, said Justin Esarey, a political science professor at Rice University who has studied the effects of peer review on social science research. That’s simply because of the standards that are supposed to go along with peer review — clearly reporting a study’s methodology, for instance — and because extra sets of eyes might spot errors the author of a paper overlooked.

The debate over peer review’s role takes on a more expansive meaning in political science, where the results of a study can quickly shape public opinion and public policy. For example, the Trump administration has used one peer-reviewed study from 2014 as a major piece of evidence for claiming that American elections are undermined by illegal voting — going so far as to set up a commission to study the issue. That a majority of researchers have found no evidence that fraudulent voting is widespread or likely to have a big impact on elections doesn’t seem to matter when politicians want evidence to justify what they already believe.

The afterlife of that voter fraud study demonstrates how political science research — peer-reviewed or not — can have immediate political implications. And that creates dueling incentives for political science: Is it more important to get work into the public while it is most relevant, or is it more important to go through the often slow process of peer review and hope that makes the work more accurate? Ten or 15 years ago, the answer would have clearly been to wait for peer review, said Nicholas Valentino, professor of political science at the University of Michigan. But he, and other political scientists I spoke with, said that norm has shifted, and relevancy is now much more important than it used to be.

Those two studies that were released in September are great examples of this trend. Both involved research that is deeply relevant to current political news, and — according to researchers I spoke with — both are flawed in ways that peer review might have caught.

“I don’t know what the right answer to this is. And I have colleagues I deeply respect on either side. I switch sides.”

Take that survey on voter suppression in Wisconsin. Kenneth Mayer, professor of political science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, was the lead researcher on a project that sent surveys to 2,400 people in two counties who hadn’t voted in the 2016 election, then published the results as a press release. Twelve percent of people replied to the survey, and by extrapolating those 288 responses to all people in those counties who were registered to vote but did not, Mayer’s team estimated that between 11,000 and 23,000 Wisconsinites could have been deterred from voting because of the state’s ID law.

But Nathan Kalmoe, a professor of political communication at Louisiana State University, said the survey left a lot of room for small measurement errors to make a big difference on results. The survey showed that voter ID-related issues played a small role in respondents’ decisions to not vote. For instance, 33 percent of respondents1 gave as the primary reason they didn’t vote that they didn’t like the candidates. Just 1.4 percent were told at the polling place that their ID was inadequate.

That means we’re talking about very small numbers of people — so small that it would only take a couple of measurement errors to alter the outcome. Say one person massaged her answers to make the socially undesirable choice of not voting seem a little less like her fault. Or another accidentally filled in a bubble he didn’t intend to. All of a sudden, the results could shift. “I view the result as additional evidence that voter ID laws probably demobilized some people, but that the magnitude is probably less than the press release indicates,” Kalmoe told me.

The other September study focused on misleading “junk news” shared on Twitter. Led by Philip Howard, an Oxford University professor of internet studies, this project tracked the locations people were tweeting from in the days leading up to the 2016 election and found, on average, a higher concentration of junk news posts in swing states. That could be read as evidence that propaganda and misleading information played a role in the outcome of the election. But the way the study was conducted calls that kind of claim into question, said Brendan Nyhan, professor of government at Dartmouth.

Most Twitter users don’t include information about their location, and Twitter itself isn’t used by most Americans. Both of those things make it difficult to take what the study found and extrapolate it into meaningful facts about what was happening nationally, Nyhan said. And Howard agreed with that assessment. Ideally, Howard told me, he’d like to see political scientists stop studying Twitter altogether, but Twitter’s data is free to use, and many other social networks’ data is not. “[We] hope the things we learn about social networks on Twitter matter to Facebook,” Howard said. But he suspects they don’t. Twitter is a bad proxy for social media use, but it’s the proxy everyone is using.

The problem was exacerbated by the fact that the study focused on tweets sent from a state, not what was actually being read or engaged with by people in that state. Even if junk news was being posted in swing states, that’s not a clear indicator of the impact it had. “This is a supply-side analysis, not demand side,” Nyhan said.

Both these studies were legitimate research conducted by respected scientists, and neither was flawed in any spectacular or unique way. Mayer told me that he thought his data was strong enough to withstand peer review — and it well could have been. So why release it before that process had a chance to happen?

The answer comes down to timing. “We wanted to contribute to public discussion,” Mayer said. “If you waited until an article has actually been published … you’re talking about a year and a half, maybe two years before the information is out there.” Political science isn’t the only field where publication before peer review is increasingly common: Biologists now “pre-publish” more than 1,000 new articles every month, more than 10 times the monthly average of a decade ago. Nor is political science the only field where researchers can struggle with long wait times before their work is published through the traditional peer review process. But the political scientists and social scientists I spoke to described a particularly uncomfortable tension between feeling that the information they had gathered was deeply important to pressing questions and that publication wait times that could keep that information sitting out of public view for as long as two years.

Social media and blogging has really become political scientists’ solution to slow peer review.

That long wait time could be a result of the length of political science research papers — upwards of 10,000 words long, compared with the 3,500-word articles more common in physical and life sciences. There also just isn’t that much space to publish research. Poli sci journals tend to come out quarterly, and one recently reported a record number of submissions: nearly 1,000 articles in 10 months, for a journal that publishes only about a dozen articles each issue. And the problem could also have to do with the fact that there’s more than one valid methodology for studying a question in political science, Esaray said. So peers don’t always agree on whether someone is “doing it right.”

But this issue with timing, combined with the desire to make research results available when they are most relevant to the public discourse, helps explain why there doesn’t seem to be a strong consensus within political science about whether releasing data before peer review is a good idea. The 12 political and social scientists I spoke with presented a wide range of opinion. “I don’t know what the right answer to this is,” Valentino told me. “And I have colleagues I deeply respect on either side. I switch sides.”

Regardless of their stance, almost all of them described having made research public prior to peer review themselves at some point or another — either speaking with a reporter, writing a blog post or sending a Tweet. They told me that bypassing peer review was sometimes necessary, enabling scientists to get publicly funded research to the public when it was most important and even improving research by allowing peers to weigh in, critique one another and craft better papers before a formal peer review.

But most of those same scientists also believed there were serious risks to bypassing peer review, and that those risks were particularly relevant for political science. The problem is that the public — and the press — tend to consider individual studies on their own and not in the context of all the other research being done on the same subject, said Dominique Brossard, a professor of life sciences communication at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who studies the public communication of science. That’s especially true when individual papers end up politicized by partisan stakeholders. Journalists can, and certainly do, write articles about individual papers where a range of scientists are given the chance to comment on and critique the work — almost like a sort of public peer review. But that doesn’t always happen, even in the most-respected newspapers. So results that make it onto the public radar can play a big role in shaping how people think and what they believe, even if that research turns out to be wrong later. That’s also true for work that’s been peer-reviewed, but if we think peer review adds any element of quality control at all, bypassing it is likely to mean more wrong information shaping public life. Not less.

And that’s particularly risky for controversial subjects like the effects of voter ID laws. While Mayer doesn’t consider his survey the definitive answer to a broad question about how those laws affect voter turnout, media reports on the survey didn’t mention that most research that has been done suggests the laws don’t have a very big impact. There are solid, ethical reasons for why you would want to be against voter ID laws, Valentino said, and there’s solid evidence that those laws are meant to keep large numbers of people from voting, whether they actually do or not. But if a study like Mayer’s is easy to pick apart, Valentino worried it could end up undermining trust in that other evidence.

Kalmoe and Esarey told me that political science journals are trying to speed the publication process up — incentivizing faster turnaround on reviewing and revising and publishing articles online rather than holding them until there’s room in a print issue. But social media and blogging has really become political scientists’ solution to slow peer review, they said. So it’s likely that we will continue to encounter situations where research reaches the public before it reaches peer review. And the basic fact is that, while scientists can speculate about risks and rewards, we don’t really know what the outcomes of this change will be. Ironically, what happens when scientists bypass the imperfect, slow process of peer review is a new frontier, one scientists are really only just beginning to study, Brossard said. “People are looking at the production of scientific knowledge and how those new communication processes may be changing, but it’s still a lot on the thinking phase … and not much in very good data,” she said. “But it’s clear that it’s changing.”

Read more: The Tangled Story Behind Trump’s False Claims Of Voter Fraud

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pascal & the Magisterium

Pascal & the Magisterium

By Paul J. Griffiths

May 4, 2020

“Magisterium” is a Latin word that designates, for Catholics, the church’s teaching authority, vested principally in its bishops. Grammatically, the word is a noun in the genitive plural and means, literally, “what belongs to teachers”—teacherly things, that is. In theological usage, the teacherly thing indicated most directly by “magisterium” is authority. Jesus had this, Scripture tells us: it was strikingly and surprisingly evident in his teaching, and he is referred to as “teacher” (magister) in Latin versions of Scripture. The church’s bishops, as Jesus’ inheritors in this respect, have it too.

Authority asks for submission, and when it’s recognized, submission ordinarily follows. When the state trooper’s blue lights flash in my rearview mirror, I pull over. That’s because she has authority and I recognize it. If I didn’t, I might ignore the flashing lights. That she does in fact have authority explains why, if I ignore those lights, things won’t go well for me in the short-term future. Authority is real: it belongs to those who have it whether it’s acknowledged or not. But for it to become active, it must be acknowledged, whether willingly (I pull over) or not (I’m forced off the road).

It’s a commonplace that teachers have authority. If you want to learn something from someone and you don’t recognize their authority to teach it to you, you won’t be able to learn it from them. This is most obvious when what you want to learn is technique: ordinarily, the teacher demonstrates the technique (the fingering that makes it possible to play the Goldberg Variations, or the best way to make a villanelle), and then you try it for yourself. If you don’t recognize the teacher’s authority by observing and imitating her demonstration of whatever it is you’re trying to learn, then she won’t be able to teach you. The authority of a teacher is ordinarily limited to its proper sphere. It’s not reasonable to expect your piano teacher to also instruct you in the proper use of a chainsaw, in rather the same way that it’s not reasonable to take the state trooper’s authority to extend to the establishment of foreign policy.

All this applies to the magisterium. It has its proper sphere, which is, roughly speaking, what belongs to Catholic faith and morals, with extensions into the governance of Catholic life by law. Its authority does not extend to instruction in the arts, or to empirically observable fact, or to mathematical truths. Generally, it also does not extend to questions of historical fact, or to politics, or to literature. If it does have anything to say about such questions, it’s because answers to them are understood to have an effect upon Catholic faith and morals. And mostly they don’t.

As with other kinds of authority, magisterial authority is effective only when it’s freely recognized, or when teachers can force recognition on those who’d rather not give it. Since most non-Catholics don’t recognize magisterial authority at all, and since the church’s teachers, unlike state troopers, have few means at their disposal to make them do so, magisterial authority is, by and large, effective only for Catholics. And it’s not always effective even for them, because sometimes they refuse to recognize it, and the bishops either can’t or don’t do what would be necessary to make them.

So here’s the picture, drastically simplified but accurate as far as it goes: the church’s bishops have authority to teach Catholics about what we Catholics should believe and how we should act. And that authority binds: we are to assent to, and act upon, these teachings. Because of the magisterium we can say, as the centurion said to Jesus, that we know what authority is and that we live our lives responsively to it. That is good knowledge to have, for all human life is lived, more or less, under authority, and it’s among the privileges of Catholic life for that condition to be explicit and theorized.

Pascal considered himself a faithful Catholic, and this was central to his self-conception.

But living a life under authority in this way comes with interesting difficulties, and with the help of Blaise Pascal (1623–1662), a peculiarly sharp thinker on this as on most other topics, I want to consider one of them. Suppose you’re a Catholic and that you take yourself to be bound by magisterial teaching: you’re aware of it and you take it seriously; you don’t shrug off difficulties in this sphere by replacing what the bishops teach with what seems good to you. Suppose, next, that a magisterial teaching is promulgated on a sharply delineated topic about which you take yourself to know a good deal. Suppose, further, that what the magisterium has to say about this topic is, so far as you can see, simply wrong. And suppose, lastly, that the situation of the church in your time and place makes silence on the matter seem to you either imprudent or improper. What do you do? Pascal was faced with just such a situation.

Today Pascal is mostly known for the Pensées, the title given in 1670 to the first publication of a collection of literary fragments left in disarray at his early death. These contain the outlines of an apologetic in favor of Catholic Christianity, a subtle and interesting understanding of the human condition with observations on death, boredom, amusement, the meaning of social and political life, and much more. The Pensées were widely read in the seventeenth century, as they have been ever since. Pascal also wrote a considerable quantity of polemical theology, mostly against the Jesuits, some of it published under a pseudonym during his lifetime. But during his life he was mostly known as a mathematician and scientist. He made contributions to the development of calculus, designed and built the first working calculating machine, planned the first mass-transit system in Paris, performed experiments that showed the possibility that a vacuum can exist—and much more. And since he died at thirty-nine, he managed to fit all this into a short career.

Pascal lived at perhaps the last moment in European history when it was halfway reasonable to think yourself capable of having significant expertise in every department of human knowledge. He doesn’t rival his younger contemporary Leibniz (1646–1716) in the range of his knowledge—who could?—but he makes Descartes (1596–1650), whom he met, and Spinoza (1632–1677) look positively provincial in their interests. But many people have great intellectual capacities. That alone wouldn’t make him memorable. Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet (1627–1704) was more of a polymath than Pascal, and vastly more learned. But Pascal could write with lucidity and force, and Bossuet, like most intellectuals, could not. Pascal, therefore, was read much more widely during his life, and has been ever since. The ability to write well, with lucidity, concision, wit, and force, is at least as important in intellectual life as the capacity to think, and since there is no profundity of thought that requires obscurity in writing, it’s surprising how many thinkers with important things to say haven’t been able to find clear language with which to say them. Pascal isn’t among them: his writings were and still are a stimulating pleasure to read.

Pascal considered himself a faithful Catholic, and this was central to his self-conception. Were he to have lost or abandoned his faith, he would have lost something as close to himself as his ability to write French or think mathematically. And so, when he found himself at odds with the magisterium, he took it seriously; and because he was the kind of man who wrote about whatever he took to be important, he wrote about this situation. In fact, he wrote a lot about it, over a period of more than ten years, which means that we have a good deal of material from his hand on which to draw.

Those who thought that the results of Pascal’s experiments must be wrong because of what the Aristotelian tradition said were ridiculous fools, and Pascal did not hesitate to ridicule them.

Pascal’s understanding of theological topics such as God, grace, church, and the nature of the Christian life were deeply influenced by the published work of Cornelius Jansen (1585–1638), a Dutch theologian and bishop. Jansenism, named for Jansen, was a Catholic reform movement of Augustinian inspiration. It was eventually judged heretical in significant part, and it disturbed French Catholicism, and eventually European Catholicism, for a century and a half after Jansen’s death. During Pascal’s life, the movement was institutionally centered on the convents of Port-Royal in Paris, and Pascal was among its principal apologists. Jansenism survives now largely as a label for a set of heresies about grace and predestination, and for a harshly rigorist understanding of the disciplines of the Christian life. That is regrettable, for some of the most knowledgeable and skilled theologians of the seventeenth century were, or later came to be called, Jansenists, and there’s more to be said in favor of their work, and of the tendency within Christianity that it represents, than such a dismissive summary permits.

Augustinus (1640), Jansen’s principal work, is a large study of Augustine, with a particular focus on Augustine’s understanding of grace as set out in his late anti-Pelagian works. The Augustinus was a foundational text for Pascal and the Port-Royalists. They took Jansen’s work to be correct as a reading of Augustine, and orthodox with respect to the doctrines of grace and human agency. They also took it to be an essential corrective to other, largely Jesuit tendencies within Catholicism that, as they believed, over-accommodated Christianity to the pagan mores of seventeenth-century France, and gave too much independence to human agency. In May 1653, Pope Innocent X issued a bull condemning five propositions on grace and attributing them to Jansen’s Augustinus. Innocent described these propositions as rash, false, impious, blasphemous, scandalous, and concluded that they were, collectively, heretical. The Port-Royalists, including Pascal, responded with a flood of polemical writing.

Innocent’s bull, Cum occasione, makes two claims. First, that a certain understanding of the workings of grace is heretical; and second, that precisely such an understanding is endorsed by a particular book—namely, the Augustinus. Pascal acknowledged at once the right of the magisterium to rule on questions about grace, and accepted that the five condemned propositions do enshrine an unorthodox and unacceptable understanding of grace. But he also insisted he had never held such an understanding of grace, and neither, so far as he could tell, had any of the so-called Jansenists, particularly not Cornelius Jansen, whether in the Augustinus or anywhere else.

Pascal’s response calls into question the right—and perhaps also the capacity—of the bishops to rule on matters of fact that can be settled by ordinary empirical investigation. Matters of that sort, Pascal argued, should be investigated by those best equipped to do so, and with the methods best adapted to the task. And the question of whether the Augustinus really did endorse, defend, or explicitly mention any or all of the condemned propositions is exactly a matter of that sort. It’s a question of fact. If you want to know what’s in the Augustinus, there’s just one appropriate method: it’s to study the book. If it includes the five propositions in question, then the references can be given, the quotations supplied, and anyone who wishes can confirm for themselves the facts of the matter. Pascal notes that no one—not Innocent, not the consultors in Rome who advised him, not those among the French theologians and bishops who had it in for Pascal and his friends—had been able to show where the condemned propositions are to be found in the Augustinus. And that, Pascal writes, is because they aren’t there. No matter what Cum occasione says, the Augustinus does not endorse or even contain any of the condemned propositions, much less all of them.

And Pascal tightened the screw. Matters of fact such as the one at issue don’t and can’t require the assent of faith. He writes, in the Provincial Letters, that “when the church condemns texts, she supposes them to contain an error that she condemns; and then it’s a matter of faith that the error has been condemned; but it isn’t a matter of faith that the texts in fact contain the error that the church supposes to be there.” In other words, whatever the pope or the bishops might say about matters of fact, positions on such matters cannot require the assent of faith. They’re simply not that kind of thing. No one’s orthodoxy or salvation depends on whether so-and-so wrote such-and-such in a particular book. People can disagree about what Jansen wrote, or about the best way to interpret it; but the magisterium has no special expertise in such matters.

In pursuing this argument, Pascal applied tools he’d developed in earlier controversies. (He was, from beginning to end, a controversialist: a man for whom the intellectual life was essentially an agonistic matter.) One such controversy had been about whether nature abhors a vacuum. Most of Pascal’s contemporaries thought that it did, and that therefore a vacuum could never be established or observed. Pascal devised experiments that showed, decisively, that a vacuum can indeed be established and observed; and he was scathing about those (again, mostly Jesuits) who thought the question about vacuums could be resolved by appealing to what Aristotle and his interpreters had written. Pascal considered that method inappropriate to the question, which was one of physics, not Aristotelian exegesis. Those who thought that the results of Pascal’s experiments must be wrong because of what the Aristotelian tradition said were ridiculous fools, and Pascal did not hesitate to ridicule them. So also here: the question about what’s in the Augustinus is one that can be investigated by ordinary means (read the book, provide the references), and those who think it can be answered by appeal to what the bishops say misunderstand both the nature of the question and the scope of magisterial authority.

Pascal continued to deny that particular matters of fact can be resolved by magisterial authority.

In 1656, after complicated backroom maneuverings in France and at Rome, Alexander VII promulgated the bull Ad sanctam, which responded directly to Pascal’s argument. Pope Alexander wrote that the five propositions of Cum occasione were drawn from the Augustinus, and are condemned “in sensu ab eodem Cornelio Iansenio intento”: in just the same sense as that intended by Jansen. This raised the temperature. Alexander didn’t back off from what Innocent had written, but rather intensified it in two ways. Now the five propositions were not merely said to have been taught or endorsed by Jansen in the Augustinus, but to have been excerpted from that book; and the sense in which they were condemned was said to be exactly the sense intended by Jansen. That second claim introduced a new problem: it was no longer just a question of what was written in the book, which is a matter of public record, but also of what the person who wrote it meant by it, which isn’t.

Pascal did not retreat. In 1657, partly in response to Ad sanctam, he restated a clear distinction between two ways of coming to assent to some claim. One is by reason, which means deploying for oneself whatever means of investigation are best suited to the claim in question. The other is by relying on authority, which means faith or trust in those best equipped to rule on the topic. Pascal subdivided this second way, faith, into two kinds. First, there’s divine faith, which means faith in what God has entrusted to the church, available to Catholics in Scripture and tradition. Here tradition means “what’s proposed to us by the church, with the assistance of the Spirit.” The church, Pascal writes, is infallible on those matters. And then there’s human faith, which means faith in authoritative people, those best equipped to teach us truths about particular matters (historical, empirical, and so on). And then Pascal writes this:

Everything that has to do with a particular point of fact can only be assented to by human faith. That’s because it’s quite clear that such matters can’t be founded upon Scripture or tradition, which are the two channels through which God’s revelation, on which divine faith is founded, comes to us. And that’s why the church can be in error on questions of fact, as all Catholics recognize.

And this:

To command those who are entirely persuaded of the truth of some point of fact to change their opinion in deference to papal authority would be to require that they abuse their reason against the order of God himself, who has given us reason to discriminate true from false so that we can prefer what we take to be true to what we take to be false.

This makes the tension very clear. In spite of what Alexander’s bull says, Pascal continued to deny that particular matters of fact can be resolved by magisterial authority, and he did that because of an epistemology—an understanding of what knowledge is and how it’s arrived at—that places conclusions about such matters beyond the scope of magisterial teaching. So if you should find yourself in the position, as Pascal did, of having what you take to be clear, even decisive evidence in favor of some conclusion about a question of fact, you shouldn’t abandon that conclusion because a pope or some bishops say the opposite.

It’s worth pausing here to note that Pascal is correct about the question of fact at issue. None of the five propositions condemned by Innocent and Alexander is to be found verbatim in the Augustinus, and if Alexander said otherwise, then he was wrong. Thanks to Google Books, you can test this at home. The 1640 Louvain edition of the Augustinus—1,463 pages of turgidly serious Latin on double-columned badly-photographed pages—can be downloaded gratis. You can read it all with the text of the condemned propositions at hand, and if you do, you’ll find that none of them has been excerpted from the book—not, at least, if “excerpted” means “taken verbatim.” And if you consult the latest edition of Denzinger’s Compendium (2012), you’ll find that its notes to the relevant sections of Innocent’s Cum occasione claim that the first of the condemned propositions is found “literally” in the Augustinus, at 3.III.13. But it isn’t—or not if “literally” means “verbatim.”

Of course, to say that the condemned propositions aren’t found verbatim in the Augustinus is perfectly compatible with saying that the condemned propositions are an adequate summary of the positions defended in that text. I’ll make no claim about that one way or the other. Here I focus on the matter only to provide a clear instance of Pascal’s strong claim, quoted above: that it’s possible for the magisterium to err on matters of fact, and that if we think we have decisive evidence that this has happened, we’d be abusing our faculties—and, I’d add, our consciences—were we to pretend otherwise.

But that isn’t the end of the story. Following Alexander’s bull—and after much back-and-forth among the French bishops, the Roman consultors, and various political factions, to which Pascal contributed with the vigor you might expect—the French vicars general demanded that priests, religious, and teachers of theology sign a formulary of submission to the bulls of 1653 and 1656, in wording designed to make it impossible to maintain a distinction between the condemned propositions and Jansen’s teaching of them. This was in October 1661, just nine months before Pascal’s death. Pascal’s last surviving written contribution to the debate, composed during the last months of 1661, speaks to a situation in which, as he sees it, the Port-Royalists have only three choices: sign the formulary without reservation, which would mean agreeing that the propositions are heretical and that Jansen taught them; refuse to sign; or sign with the reservation that the signature has to do only with matters that concern the faith—i.e., not with the question of what Jansen did or didn’t write or intend or teach, but only with questions of substance about the workings of grace.

Pascal explicitly rejects the third option. By now, he writes, “it’s a point of doctrine and of faith to say that the five propositions are heretical in the sense given them by Jansen.” To sign the formulary, then, is to submit to the denial of the-five-propositions-in-the-sense-given-them-by-Jansen. That complex object can no longer be disaggregated into its components (the five propositions on the one hand; Jansen’s teaching on the other). Attempts to do so have been ruled out by Ad sanctam and the formulary. If one signed the formulary, one’s signature meant submission to all of it; anything else would be bad faith. It would be “abominable before God and despicable before men.” But it’s not clear from this last surviving writing on the matter which of the other two possibilities—signing without reservation or not signing—Pascal endorsed. He died the following August.

At first blush it might seem clear which option Pascal must have favored. If, as he’d been consistent in arguing for the preceding six years, the magisterium’s authority doesn’t extend to matters of fact, and yet explicit submission to a teaching on just such a matter was now being required of French Catholics, shouldn’t he have refused to sign? Wouldn’t signing have been acknowledgement of a kind of authority the bishops don’t in fact have? Perhaps. But it seems to me that there’s something else Pascal might have done—and some evidence to suggest that it’s what he did.

The evidence: First, it’s clear that by late 1661 Pascal was at odds with other Port-Royalists on the question of the signature. The disagreements circled around whether the fact/doctrine distinction could be maintained, whether it was proper to sign with reservations, and whether it was proper to sign at all. That there were such disagreements shows at least that Pascal’s final position wasn’t identical with any of those held by other prominent Jansenists in 1661 and 1662, and since those positions were, essentially, sign with reservation or don’t sign, it’s at least possible that Pascal advocated signing without reservation. Second, there’s some (disputed) evidence in support of the view that Pascal died in full communion with the church, having confessed, received the last rites, and, during the last few days of his life, fully acknowledged to his confessor the right of the church to require his assent to the claims of the formulary. That’s the sworn testimony given after Pascal’s death by the priest who attended him in his last days. This testimony was accepted by the bishop of Paris, who’d commissioned an investigation into Pascal’s death in response to a request that his remains be disinterred from their burial place because he was a heretic who’d died separated from the Church. And third, there’s evidence (again, not probative) that close to the time of his death Pascal asked Jean Domat, to whom his papers were consigned, to destroy his writings on the signature if the religious of Port-Royal found themselves under persecution, but to preserve and publish them if they’d submitted. That report makes more sense if Pascal finally advocated signing without reservation.

Your task as a Catholic thinker is always to do the best you can at what you’re thinking about.

Pascal’s case shows with unusual clarity what it is to hold together two judgments that might at first seem incompatible, and what it’s like to act consistently with such a balancing act. The first judgment is: I’m convinced that p is the case. The second is: I see that the magisterium teaches not-p, and I acknowledge its authority to do so. Acknowledging that an authority teaches not-p doesn’t require you to abandon your assent to p (Pascal never abandons his view that none of the five propositions is found in the Augustinus). What it does require is submission (the signature) to the authority of the teacher who teaches not-p. Not to acknowledge that authority would be, in the Catholic case, to separate yourself from the form of life in part constituted by such an acknowledgment; it would be to look the state trooper in the eye as she asks you to roll down your window and say, “I don’t recognize your authority to direct my action; I’ve nothing to say to you.” You may do that. But doing it comes with a price: it’s the price of removing yourself from the form of life in which state troopers have authority to enforce local laws. That, mutatis mutandis, wasn’t a price Pascal was prepared to pay in the Jansen case, and I’m with him on that. Within the Catholic form of life, the magisterium does in fact have authority to do what it did in that case.

But acknowledgment and submission don’t require pretense. If it seems to you that such-and-such is the case (that the five propositions aren’t in the Augustinus), then clarity of thought and strength of conscience not only don’t require you to pretend otherwise, but require the opposite: when occasion demands, you must say that what seems to you to be the case does in fact so seem, and when relevant you must give your reasons for this judgment. Theologians call this expressing a doubt: I see that the magisterium teaches p, but, so far as I can tell, not-p is the case, and here’s why. We’ve seen Pascal doing this, con brio. The modifier “so far as I can tell” is important. You might be wrong (that’s always true), and seeing that the magisterium seems to be teaching that you are should place your sense of your own rightness under pressure. Pressure of that kind is usually a good thing for the intellectual life: it clarifies conviction by accentuating difference.

The pressure of authority had at least one very clear effect on Pascal’s thought: it led him to suggest that when the magisterium says that so-and-so’s teaching of such-and-such is heretical, the right response is not to try to disaggregate the teaching (separating the so-and-so from the such-and-such), but rather to treat it as a complex whole. That’s what Pascal did in his last surviving letter about the formulary. The nature of that complex whole then requires further clarification. Maybe the best way to describe it is heresies-about-grace-insofar-as-they-are-endorsed-by-Jansen; or maybe it’s whatever-Jansen-wrote-that-supports-this-heresy, or grace-heresies-best-labeled-“Jansen’s”—and there are more possibilities. Once disaggregation is rejected new possibilities for thought open up, both for the speculative theologian (Pascal) and for the teaching church. One such new possibility appeared, as we’ve seen, in Alexander’s Ad sanctam: he develops what Innocent had written in Cum occasione by mentioning the sense in which Jansen intended the five propositions. This, as I’ve noted, postulates an extra-textual something, and moves everyone’s thought away from the textual particulars of the Augustinus and toward something else—a trajectory of thought, an implied grammar, or some such. This magisterial move wouldn’t have occurred without Pascal’s polemics; and those, in turn, wouldn’t have occurred without magisterial pressure. The benefit is mutual, and is the result of the magisterium doing what it should and of a theologian doing what he should.

The other question that Pascal’s case raises and illuminates for us is about the place matters of fact have in magisterial teaching. Suppose we understand a matter of fact to be one capable, in principle, of exhaustive investigation by observation. One example: the presence of a sequence of words in a particular book—affirmed, as we’ve seen, variously, by Innocent X and Alexander VII in the case of Jansen’s Augustinus. Another example: the involvement of a Roman official named Pontius Pilate in the trial, condemnation, and execution of Jesus of Nazareth—affirmed scripturally and credally (“suffered under Pontius Pilate”).

Pascal came to see that his attempt to maintain an impermeable distinction between matters of this sort and matters of faith and morals couldn’t be sustained. But the attempt is helpful to us in two ways. First, it shows that when the magisterium instructs about matters of fact, as it often does, it doesn’t do so with any concern for those matters considered in themselves. Pontius Pilate is interesting to the church only because he was involved with Jesus; had he not been, the church would have had nothing to say about him. It follows from this that it’s a misconstrual of the church’s teaching about Pilate to treat it like an encyclopedia entry, from which data about Pilate can be extracted and considered independently from the story about Jesus. This is compatible with the thought that some things said about Pilate are incompatible with the church’s teaching. That would be true, for example, of the statement “Pontius Pilate was actually in Rome when Jesus was tried.” If you’re a faithful Catholic and you find yourself believing that statement (perhaps you’re a historian and you’ve come to think that this is what the evidence shows), then you’ll find yourself in a position similar to the one just discussed: believing something incompatible with what the church teaches, while also affirming the church’s authority to teach what it teaches.

But there is an interesting, if subtle, difference. Pascal’s insistence on an impermeable distinction between matters of fact and matters of doctrine, and what I take to be his later abandonment of that hard distinction, shows that the tension between the church’s teaching about Pilate and the historian’s findings isn’t best understood as a direct contradiction. It’s not as it would be if you find the church teaching it’s not possible for women to be ordained to the priesthood while you find yourself believing that it is possible. That’s a direct contradiction. But in the Pilate case, the church teaches about Pilate only in his relation to the figure of Jesus: Pilate has no significance for the church outside that relation. His name serves as synecdoche for something like “empire-as-related-to-Jesus.” The point of the church’s teaching about him isn’t to make an entry into a chronicle of events, but to locate Jesus in time and place, and to show something about the significance of his trial and death. Those purposes can be served in other ways, and, so far as I can see, nothing much hinges upon whether the name of the Roman official who condemned Jesus was Pontius Pilate. That much remains of Pascal’s insistence that no one’s salvation rests upon a matter of fact.

And that is the final gift that the Pascal case gives. It provides Catholics who want to think about matters of fact spoken to in one way or another by the magisterium with a fundamental guiding question: What is the significance for the life of the church of the magisterium’s teaching about this matter of fact? There will always be some such significance if, as I’ve suggested, the church never teaches about matters of fact simply as such. Whenever we find ourselves in disagreement with the magisterium about a matter of fact, we should begin by trying to understand what that significance is.

If you want to think as a Catholic about the Lord God, about the human person, or about the good society, you’ll find the magisterium there as a companion and a blessing, albeit one that sometimes comes with painful difficulties. Pascal’s case, on my reading of it, shows how that blessing may be welcomed and the difficulties embraced, to the benefit of all concerned. If you never find yourself in a situation like that of Pascal—seeing that the magisterium teaches one thing while, as far as you can tell, the opposite is true—that is likely an indication that you’re not thinking hard enough, and therefore not doing the job the church needs you to do as a thinker. If, when you do find yourself in Pascal’s situation, you pretend to yourself and the world that you don’t take to be true what you do take to be true, you’re also failing, this time by treating the magisterium as if it were Big Brother and concealing the truth out of fear. Your task as a Catholic thinker is always to do the best you can at what you’re thinking about; to be as clear as you can about the conclusions to which your thinking leads you; to delineate, as clearly as possible, what differences you have with the magisterium’s teaching; and, at the same time, to acknowledge the magisterium’s authority, recognizing that you are more likely to be wrong than the church is. All that together makes a delightfully difficult task. Neither the delight nor the difficulty should be forgotten or covered over. Together, they’re the Catholic thing.

Issue:

May 2020

Go to the article

0 notes

Text

On Liberal Smugness

After her Not the White House Correspondent’s Dinner, Samantha Bee was asked by Jake Tapper about liberal smugness and she shrugged it off. For many liberal comedians and commentators that self-assuredness doesn’t feel like smugness. It seems more to me that what they see as smugness is an allergy to bullshit. As Vox’s Carlos Maza argued, comedians cover Donald Trump better than journalists because they have a low tolerance for bullshit.

The many expressions that liberals have for Trumpism bullshit may come off as smug but it comes in equal part from, if not more than, a feeling of horror. Comedy and mockery are easier ways to deliver scary and uneasy things. Right now liberals are scared of a president who has plainly said he thinks that the Constitution’s archaic rules have prevented him from enacting change. But comedy and mockery deliver a small modicum of power to belittle the man, and that power to freely mock and deride our leaders, is part of that Constitution.

As Noah Smith pointed out in a recent Twitter thread, liberals seem smug because so many of the topics of debate in the 00s have favored liberal opinions (gay marriage, Iraq, global warming, Bush tax cuts, even Obamacare). As he puts it: “When conservatives tell liberals "Stop being smug", what they really mean is "Stop gloating. You won, stop rubbing it in.”” Smith goes on to argue that currently liberals (or center-left) don’t have a clear message on how to face the current arguments such as the Opioid crisis, economic growth, trade agreements, monopolies and others.

I see some problems with this: namely outside of Trump’s blustery moments of bemoaning opioids and trade agreements on the campaign trail, conservatives don’t have any clearer of a message than this. Essentially, Trump has identified or magnified attention on these particular issues by saying they’re bad. I’ll also add, that many of the aughts arguments, especially global warming, are still being litigated in the public sphere. Healthcare as well. These things are not solved and necessarily separate from the things that Smith says are this decade’s, or more accurately this term’s, problems. Also, it is not the business of liberal commentators and comedians to set the messaging agenda for the Democratic party.

When Bee shrugged off the liberal smugness problem she said that she made the show for “people like [her].” And it’s important to circle back to that problem. She is constantly outraged because there’s outrageous shit going on. Why is 9/11 truther and Sandy Hook denier Alex Jones an informal advisor to the President? Why was Sebastian Gorka, anywhere near the White House? Why were the 16 instances of “[unintelligible]” in a recent Trump interview with the AP.

Part of what I think is codified in “liberal smugness” is a conservative attitude that many people on TV openly criticize one party more than the other. There is no conservative Jon Stewart and there hasn’t been and it’s unlikely there ever will be. For that matter there is no left wing rabid conspiracy theorist in the ear of major political figures. To my thinking, Jill Stein might be the closest comparison some of the insane shit the both Trump and his minions put out there. Until Trump came onto the scene it appeared that the far left might own the Anti-vaxxer phenomenon, but let’s not forget that Tea Partier Michelle Bachmann was propagating this six years ago.

Democratic Politicians certainly need to be better with their messaging on these issues and offer clear solutions to expressed problems. But I am decidedly with Samantha Bee and her shrugging: Exposing bullshit is not a “smug” thing to do. And the goal may not necessarily be to convince large swaths of conservatives to join their thinking, it may just be a way to reassure liberals, “hey, you’re not the crazy. This world is insane and I’ll use my microphone to shout into the void how absurd it all is.”

#samantha bee#not the white house correspondents dinner#jake tapper#noah smith#carlos maza#liberals#liberal smugness

1 note

·

View note

Text

N.E. Simmonds, Constitutional Rights, Civility and Artifice, 78 Cambridge L J 175 (2019)

Abstract

The value of civility is grounded upon acceptance of the legitimacy of moral disagreement and the need for mutual respect and cooperation in the face of such disagreement. The distinction between rights and goods plays a fundamental role in the form of civility espoused by liberal society. Current models of constitutional rights and proportionality, in a variety of ways, erode that distinction and thereby place the liberal model of civility in jeopardy.

I. After Eden

A tradition of political thought that stretches back to Plato and Aristotle views the institutions of the political community as serving to foster excellent lives for human beings. Law plays an important part in this picture: it helps to inculcate habits of virtue; it helps to protect the virtuous from the predations of the wicked; and it helps to sustain other institutions (such as property, the market and the family) which themselves foster excellence and encourage virtuous habits. But law does none of these things alone. For this tradition, law is only one part of a more complex fabric of practices and institutions with its centre in a single set of values. Those values permeate the whole and provide the unity that makes political association possible.