#diphthong discusses

Text

I know I haven't existed on here in a good while, but I just found this quote in my random ramblings discord channel where I slap whatever pops into my head at all hours and

"She called me a jeebus-doubting charcuterie board and I have never felt so seen"

What in the world was Past Diphthong thinking about???

#hello all! I am alive!#alive and well just very very busy lol#someday my lurking may turn back to participation#but for now I lurk#writeblr#my writing#diphthong discusses

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tlette Tlursday #2

Today’s topic is syntactic gemination! On Lexember 4 (lé) I talked about this phenomenon for the first time, and @yuk-tepat asked “Is there a diachronic explanation for why syntactic gemination occurs?” The answer was a bit too long for a reply so it’s getting its own post.

So first of all I basically just stole this idea from Italian. It also occurs in Finnish, but I didn’t know that until quite recently. I first came across the idea in a video about Italian pronunciation, which discussed the phrase tra poco, meaning “soon.” The word tra is a preposition coming from Latin intrā, which had a long final vowel. Even though the length of the vowel has been lost in Italian, it is preserved as the gemination of a following consonant, so tra poco is pronounced as /trap.ˈpɔ.ko/ (or /tra‿p.ˈpɔ.ko/ if you want to show that explicitly).

In Tlette it comes from the same general place. Proto-Tlette (or Kaleate) allowed CVV syllables, but a later sound change basically transferred the length from a vowel or diphthong onto the following consonant. This is the source for many of the doubled consonants within Tlette words. The word elle was originally *eele, with a long first vowel. The vowel got shorter but the consonant got longer, to preserve the timing of the word as a whole.

The same thing happened with no’’i, previously *neuʔi. There the first syllable had a diphthong instead of a long vowel, but the double vowel *eu squished down to *ew, which later became o.

Syntactic gemination is just this same process occurring at word boundaries. The word lé was originally *lee, and just like intrā shortening to tra it shortened to lé and caused following consonants to lengthen. If the next word begins in a vowel or a consonant cluster, it isn’t affected.

The accent mark in lé is just there to show that the gemination could happen. The singular nonhuman pronouns are actually a homophone pair, ku and kú (nominative and accusative respectively, originally *ko and *kol). They are pronounced identically in isolation, but only the latter causes gemination. It originally ended in a consonant and not a long vowel, but before the length-transfer sound change occurred the final l vocalized to make a diphthong.

Since original *o became u, in modern Tlette all instances of non-nasal o come from diphthongs like eu. That means that all words ending in o trigger syntactic gemination, and within words o is always followed by a geminate consonant or a cluster. Because this is so consistent, single-syllable words ending in o (like po) don’t need to be marked with an accent, since there’s no possibility for a homophone that wouldn’t cause syntactic gemination.

The same process also affects certain consonant-final words, like rıkk, originally *ruuqa. The final vowel was lost and the same transfer of length from the first vowel to the following consonant occurred, but the consonant is only pronounced as long when the next word begins with a vowel.

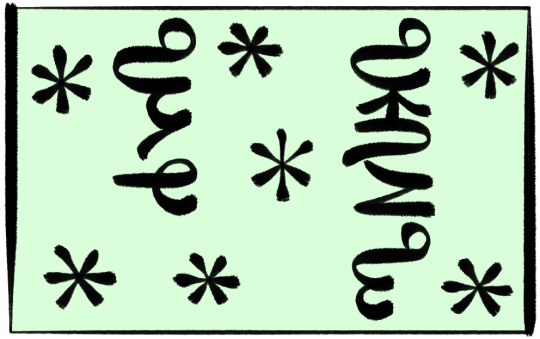

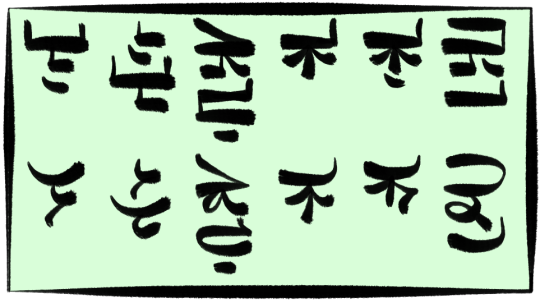

In the Tlette alphabet, there is a small accent-like mark that indicates both stress and gemination. It isn’t 100% consistent, but it generally follows stressed vowels and precedes geminate consonants, and is the equivalent of the accent mark for words like lé. In cursive Tlette, this mark joins with the preceding stroke. Below are, in order, lé, elle, no’’i, ku, kú, and rıkk. Since the geminate in no’’i follows an o, the mark is absent from that word.

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Would you say that a banjo's sound can be accurately described as a "twang"?

I would say it depends on the style of banjo being played! I have zero issue calling picking styles twangy and do so myself. But when people less familiar with the music use it as an automatic designator, I feel it demonstrates incomplete assumptions of what a banjo is (alongside regional assumptions - as if pairing it aurally with a spoken Southern "drawl").

The prototypical banjo sound today is Scruggs style picking. The picking hand places three picks on your first three fingers. This provides a sharp, snappy sound. The fretting hand creates ornamentation that slides about the string, hitting blue notes, gliding in and out of dissonance and consonance; the result feels like the twaaaang of an arrow going off a bow, or the sliding diphthongs of Southern American Englishes. This is twangy and it's yummy.

youtube

If someone watches a clawhammer banjo picker and goes, "Oh! I love the twang!" I suspect they're judging by the visual of a banjo and its stereotypical associations, not judging what they're hearing. Clawhammer banjo utilizes strums, alternating your thumb striking a note and your fingers brushing down the strings. There are no picks. You are often playing banjos with different construction (open back versus resonator). The resulting tone is mellower. Maybe you still think it sounds twangy, and that's fine, but there's no denying it's a very different sound than the three-finger picking styles like Scruggs style.

There are many, many, many more banjo styles. I'm simplifying for the sake of simplifying. But Rhiannon Giddens, for instance, does not play with a twang to my ears.

youtube

Second, I feel like "twang" suggests "down home bluegrass." Like there's connotations of (stereotypical Southern) region, (rural) class, and "non-properness" there (contrasting, say, how classical music has a genteel connotation). But banjo can be heard in everything from 1920s jazz to ragtime to Celtic. And even bluegrass has high variability, with different eras and bands sounding like the rock side of the 1960s Folk Revival, modern rock, country, old-time, classical, jazz, or whatever the heck they want to throw in there.

That "twang" suggests "down home bluegrass" could be my own associations clouding judgment with the word twang, though. There's no denying something like Vess Ossman's plectrum style in ragtime has snappy twang to it. So I could be overassuming what other connotations people associate with the word "twang."

youtube

There's a third aspect at play here -- I find banjo's tonal variations huge. I'm sure many folks think, "Yep, that banjo sounds like a banjo," and that's the start and end to it. For me, the banjo's colors are highly variable between instruments and players.

I prefer using detailed descriptors to explain what I hear between different banjos and pickers. Ralph Stanley's tone is bright and narrow, sharp and thin and brittle like fingernails, but ancient. Earl Scruggs's tone sounds earthy. It's deep browns and the power of dirt, thrown into a man whose fingers are so precise they're a machine gun shower of notes. Kenny Ingram is pure machine gun - much sharper, weaponistic in its attacks. Béla Fleck's tone sounds silvery. It's pristine, light, delicate, gliding off the top, sonic embroidery suited for marble halls. They sound nowhere near the same even when playing the same notes because their tones are that different. Why would I call Béla twangy when his tone's so glitterily elegant?

youtube

Banjo is an instrument with an unusual amount of tonal customization possible. And I do mean there's lots here about what affects tone, how much you as an owner can alter it, and how variable the final product's sound is. Banjo is juicily customizable. Banjoists turn into mad scientists taking apart their instruments to modify them according to their sonic preferences. It would be a whole other post to discuss what gives the banjo its tone and how that can be modified - and frankly I've only learned the surface.

I'm mostly being picky (ba dumpt tssh get the pun?) when I say, "not all banjos, banjo pickers, and banjo styles twang." I feel off when someone calls certain old-time styles twangy, but I groove when people call a good Scruggs style twangy. In the end, language is flavor, and I may use my flavors of description differently than the next guy.

In general, though, yeah, I'd say "twang" is a fine description.

#haddock to myself the other day: I'm going to make my posts shorter on this blog to be more accessible#haddock right now: writes three thousand hundred words :P#^.^ fun topic tho#peachdoxie#thatbanjobusiness#General Banjo Business#ask#ask me#that banjo business

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

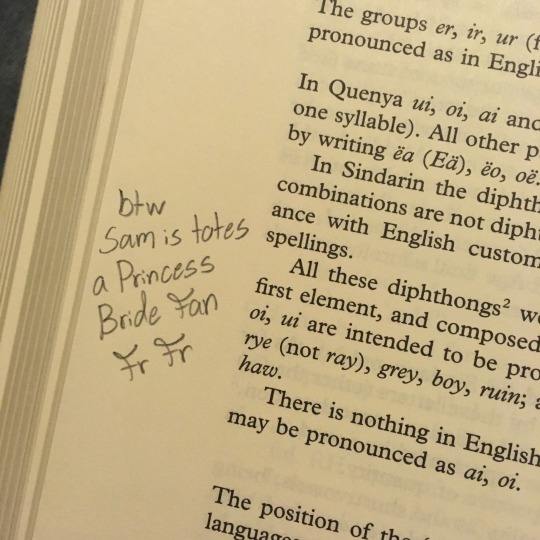

It's actually canon that Sam loves the Princess Bride it's way wayyyyy deep in the Appendices and easy to miss! But you're right once again XD ~meg

GASP! You’re right, Meg! I found it! Right here, in Appendix E, page 1116, right next to the discussion of diphthongs in Quenya!!

…..No idea why it’s there specifically, but who am I to judge the great late Jirt??

(Re: this post)

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frislandic Historical Phonology

Ok so what the hell is with this phonology? Why this three-way aspiration contrast? What's with those aspirated labials? Those mutations? And why so many goddamn diphthongs?

All these questions and more will not really be answered but there'll at least be some more relevant information.

So Proto-Frislandic is a very nebulous entity, because many of the details of reconstruction are still hotly contested, some of which we'll discuss in a moment. For now the general consensus is on a reconstructed inventory like so:

*p *t *c *k

*pʰ *tʰ *cʰ *kʰ

(*s) *ʃ

*m *n

*r *l

*i *e *a *o *u

Roots had a C(n, l, r)V(ː)(n)CV structure with nouns and a C(n, l, r)V(ː)C- structure with verbs. *r did not occur root-initially, and do not seem to have been particularly common root-medially either. The exact quality of *l is also of some debate: some authors suggest it was likely some kind of lateral fricative (which is its primary reflex root-initially), rather than an approximant, but a resolution on this issue is likely impossible. *ʃ is also of uncertain quality, but it was likely retracted and slightly retroflxed, not palatal.

Authors tend to disagree most on the palatalised series, as there were probably three different sources for this in Pre-Proto-Frislandic: underived, palatalised dentals and palatalised velars.

The palatalisation of dentals before *i was most consistent (even today dentals never occur before reflexes of *i in native roots and there are scarce occurences even in loans; see e.g. zivl 'devil' and kerz 'believe' from Irish diabhal and creid respectively) and was a semi-productive part of derivation even in Proto-Frislandic, particularly for deriving basic agent nouns from verb roots. However it should be noted that paltalised *tʰ gave (not yet contrastive) *s not *cʰ (which in most varieties later merged with *ʃ to give modern /s/) so e.g. *kʰlat- 'return' → *kʰlaci 'returnee', *trotʰ- 'follow' → *trosi 'follower'. In modern Frislandic these are kald → kælz and dost → dors respectively, though note the nouns are lexicalised as 're-immigré, returning expat' and 'disciple' respectively. Some authors propose a distinct *t͡s from palatalised *t on the basis of some dialectal reflexes.

There's also evidence of palatalisation of velars, but this is less consistent outside of again agent noun forms (e.g. *ʃuk- 'speak a language' → *ʃuci 'speaker', *ʃrikʰ- 'sweep, brush' → *ʃricʰi 'sweeper'; modern sug → suz 'interpreter', sjisk → sjisj 'brush'). Some authors propose an additional series of indeterminate quality (some say labio-velar, some uvular) to explain forms such as *kriːta 'gland', modern girið, *kʰiːta 'sheath', modern kijð 'vagina'.

And there are still a number of palatals which cannot be explained through any kind of palatalisation process, such as *tʰoc- 'come', *coːta 'body', *cʰoːnti 'urine', modern toz, zuoð, sjuojn.

Additionally, while *tʰ *kʰ are still aspirates in most varieties to the present day, *pʰ *cʰ were likely already fricatives *ɸ *ç at the Proto-Frislandic stage. This shift was likely an early motivator for the breakdown of the aspiration dissimilation Grassman's Law-style which was present in pre-Proto-Frislandic and still is the general trend for native vocabulary and the formation of inanimate plurals (even seeing extension to loanword, e.g. gekirk /kəˈkʰirkʰ/ 'churches'), but is otherwise no longer productive (see previous example).

When it comes to the vowels, since unstressed root-final vowels were later lost, the contrasts in root-final vowels can be difficult to reconstruct outside of the context just outlined. The main contrast that can be adduced is between high *i *u and low *a *e *o, as these exhibit differing morphophonological behaviour, as well as being the motivation for the allomorphy of the modern Frislandic animate plural -u~o and genitive -i~e.

Already in Proto-Frislandic, the high vowels *i *u underwent syncope in certain morphololgical contexts, most notably in compounds, but traces of syncope in other contexts can be seen elsewhere (e.g. the instrument noun suffix -ll from *-li-tV). As such, there is a split between compounds where the first root ended in a high vowel and thus exhibited syncope and those where it ended in a low vowel and did not. In the former case stress was placed on the first syllable, the second later ended up undergoing vowel reduction and the consonant cluster was simplified, sometimes in rather radical ways (the full set of which will have to wait till another time), for example:

*citʰu + *paːʃa → *tiʰpːaːʃa to zitt 'jaw, chin' + bar 'stone' → zippar 'teeth'

*pʰonci + *pʰraːci → *pʰoɲpːʰraːci to onz 'sheep' + æræj 'bearer' → ojmpræj 'shepherd'

*traːkʰu + tʰaːci → *traʰtːaːci to darak 'length' + tæj 'dog' → dæstæj 'weasel'

*kʰoːku + *tuʃu → *kʰotːuʃu to kuo 'swamp' + dus 'berries' → koder 'cranberries'

*iːsi + *kʰreta → *iʰkːreta to ijr 'seaweed' + kærd 'bread' → ikkreð 'laverbread'

*tʰolu + *ʃeːli → *tʰolːeːli to toll 'shell' + siel 'slug' → tollel 'snail'

Note also that verb-noun compaunds exhibit the same behaviour.

*poːt-pʰaːli → *popːʰaːli to buoð bind' + æl town' → bopæl 'league'

*sinc-kʰuːnu → *siɲkːʰuːnu to sinz 'soak' + kwn 'bone' → sinkun 'bone broth'

*pent-tʰaːci → *pentːʰaːci to bænd 'guard' + tæj 'dog' → bentæj 'guard dog'

On the other hand, where the compound ended with a low vowel, syncope did not occur, stress was on the third vowel (the root vowel of the head of the compound) and the only substantial change was and is still lenition. This kind of compounding remains at least somewhat productive into Modern Frislandic, even with forms that would historically have behaved like high-vowel roots.

*maːte + *pala → *maːtepala to mæð 'pine tree' + ball 'seeds' → mæðvall 'pinenuts'

*mukʰa + *tuːkʰa → *mukʰatuːkʰa to mukk 'pigs' + dwk 'shark' → mukkðwk 'angel shark'

gat 'street' + tren 'train' → gættren 'tram'

sjuj 'tally, record' + kist 'box' → sjujkist 'computer'

So how did we get to modern Frislandic? Well I'm not going to go into all of the details but there's a few key points to make.

Firstly, vowel length an consonant length got slightly re-jiggled. Basically, single consonants after stressed short vowels became geminated (this was probably also when long vowels after geminates from cluster resolution shortened). Remaining single plain consonants would voice and then lenite intervocalically, while geminated forms of the aspirated stops *tʰ and *kʰ would be pre-aspirated, the singleton versions remaining post-aspirated. Note that this does not include the already post-aspirated geminates from cluster resolution seen above. The long vowels did remain different in quantity, as there were subsequent shifts in quality, including breaking (producing the first set of diphthongs ie uo ij w /iə̯ uə̯ əi̯ əu̯/). Furthermore the long vowels retained their quality when unstressed while the short ones were reduced. Thus:

*ʃuci → *ʃucːɨ → suz /syt͡s/

*citʰu → *ciʰtːɨ → zitt /t͡siʰt/

*kʰreta → *kʰrætːə → kærd /kʰært/

*kʰoːku → *kʰoːgɨ → kuo /kʰuə̯/

*kʰotːuʃu → *kʰotːɨʒɨ → koder /ˈkʰutər/

*maːtepala → *mæːdəbalːə → mæðvall /mæðˈβɑɬ/

Some other major changes to note. Firstly, the aspirated *pʰ and *cʰ behave differently. *pʰ (when not already geminated because of a former cluster) lenited to *ɸ and was sunsequently lost regardless of length and position (hence the discrepancy between the exonym Fri[sland] *ɸriːka~*ɸriːkaʃi-kʰuta and the modern reflexes Iri~Irijkud /ˈiri/~/ˌirəi̯ˈkʰyt/). Similarly, as *cʰ was likely lenited to *ç early on it participated in lenition in the same manner as the plain obstruents, resulting in its alternation being voiced-based rather than aspiration based.

A second change to the vowels not yet mentioned has to do with umlaut. The default reflex of Proto-Frislandic *e in modern Frislandic is /æ/. However, there was a process fo umlaut before original from vowels *i *e in a following syllable which resulted in its retention as a mid-front /e/. In this same environment original *a was fronted to /æ/ as well. The distance this umlaut effect can travel seems to have varied across Frisland: in some regions (in particular the capital Ojbar where the standard derives from) it only seems to have travelled one syllable, suggesting that in these cases it probably arose as a result of co-articulation effects on consonants, though there was seemingly a subsequent process of /æ/-dissimilation which produced forms such as bentæj /ˈpentʰæi̯/ 'guard-dog' (as opposed to *bæntæj). In other areas this instead seems to have been more like true umlaut, and these regions also tend to have expanded vowel systems due to the application of umlaut to the back-rounded vowels (but that's a story for another time).

Finally, those word-initial clusters underwent metathesis relatively late, with complete metathesis with short vowels and a kind of 'liquid-interpolating' with long vowels (see e.g .'weasel' above). some more educated speakers do pronounce such initial clusters in loanwords, but not always. Furthermore, this change only occurred word-initially, so there are still a lot of alternations of the kind gald~gelad /kɑlt/~/kəˈlɑt/ 'battle(s)', soroð~seruoð /ˈsuruð/~/səˈruə̯ð/ 'spear(s)' and bænll~bonæll /pænɬ/~/puˈnæɬ/ 'walking stick(s). This has even undergone extension to loanwords in some cases, such as koron~gekruon /ˈkʰurun/~/kəˈkʰruə̯n/ 'crown(s)' or sjuru~sjirw /ˈɕyry/~/ɕiˈrəu̯/ 'screw(s)'.

So yeah a bit long, hopefully I'll actually get onto dialectology next time.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lindsay J. Whaley and Fengxiang Li “Oroqen Dialects”

This paper surveys some dialectal data from Oroqen varieties. Authors conclude that Oroqen can be divided into the following four dialects: Western, Central, Northeastern, and Southeastern.

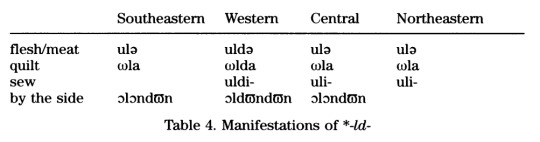

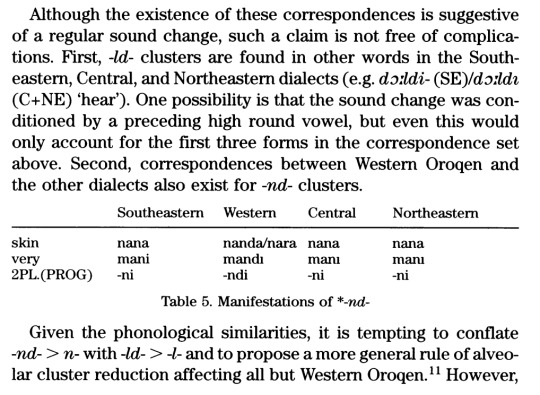

One of the phonological developments distinguishing Oroqen dialects is what Whaley & Li call “manifestation of *-ld-”:

At first sight it seems like *-ld- is simplified to -l- in all dialects, save Western. However, things are somewhat more interesting.

This discussion shows a lack of familiarity with the most basic facts of Proto-Tungusic reconstruction. The words in Tables 4 & 5 do not reflect Proto-Tungusic *-ld- and *-nd-. Instead, they reflect *-ls- and *-ns-! Cf. the following Proto-Tungusic reconstructions (I use Doerfer’s system here, but the correspondences for *ls and *ns were recognized as such already by Tsintsius): *ölsä ‘meat’, *pulsa ‘quilt’, *nansa ‘skin’, *mansï ‘very’, *-nsi ‘2 sg’ (2PL in Table 5 must be a mistake) vs. *dooldï- ‘to hear’. The verb ‘to sing’ is more complicated: apart from Oroqen, it has reflexes in Ewenki, Solon and Ewen (thus, only in North Tungusic), and the Proto-North-Tungusic form can be reconstructed as *ǯaandaa-. However, one of the common North Tungusic innovations is the simplification *-nd- > *-n-, so Proto-North-Tungusic *-nd- must have a different source. Perhaps, this word is a loan from unknown source, borrowed after the change *-nd- > *-n-.

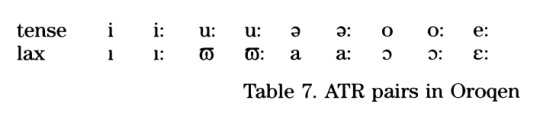

An interesting feature of Oroqen is its symmetrical vowel system with tense (+ATR) / lax (-ATR) pairs:

Southeastern Oroqen differs from other dialects by merging /i/ and /ı/:

The authors point out that “An even more dramatic restructuring of the vowel harmony system has occurred in most Tungusic languages. Only Oroqen and Solon seem to have preserved a perfect symmetry between tense and lax pairs, except now for the Southeastern dialect, where the system is moving toward asymmetry”.

Indeed, Proto-Tungusic is reconstructed with a very similar symmetrical system: +ATR *i, *ii, *ü, *üü, *ä, *ää, *ö, *öö, vs. -ATR *ï, *ïï, *u, *uu, *a, *aa, *o, *oo + some diphthongs. A common innovation of North Tungusic languages (including Oroch and Udihe) is a change *ü > *i, *üü > *ii, so Oroqen symmetrical system cannot directly continue the Proto-Tungisic vocalism. While Oroqen /u/ continues Proto-Tungusic *ö (e.g., in Oroqen urə ‘mountain’ < PT *xörää ‘id.’), the origin of Oroqen /o/ remains unclear to me. Oroqen words cited in the article do not contain this phoneme.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

There's this interesting trend I've noticed on posts about pronunciations on tumblr with regards to diphthongs. I don't know what's wrong with how they're taught or how most people understand them but there seems to be persistent confusion about what they actually are.

There are a few words that have had discussions on here specifically relating to whether they have 1 syllable or 2. Off the top of my head "our" and "poem" are the obvious examples but I'm pretty sure I've seen others.

Anyway, on all of these types of posts, I can invariably go into the notes and find someome saying something like "While there are two ways of pronouncing this, they're actually both 1 syllable, one of them just has a diphthong!", and I'm sort of curious where this view comes from. I've seen one person state that any two adjacent vowels are a diphthong and thus part of the same syllable because they don't have a consonant in between, but I don't know if that's a widespread understanding.

With "our", while one pronunciation has a diphthong, that's not it's only vowel, so you end up with /aʊ̯.ɚ/¹ and /ɑɹ/ in GA. And with "poem", the two common GA pronunciations are /poʊ̯m/ and /ˈpoʊ̯.əm/² both of which have a diphthong. Is it just the naïve definition from the previous paragraph and non-linguists viewing /oʊ̯/ as a single vowel that's leading people to see /oʊ̯.ə/ as a diphthong that can act as the nucleus of a single syllable?

¹ I guess this could be analysed as a triphthong but I'm not aware of GA being analysed as having triphthongs, I've only ever seen them in conservative RP.

² As a Brit I would say the second syllable has /ɪ/ but I've seen /ə/ more commonly here for American accents.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 3. The Sounds of Language

Phonetics:

It encompasses the examination of speech sound production and pronunciation. Over time, the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) has been developed and refined.

It is mainly on articulatory phonetics or the production and articulation of speech sounds.

Additionally, there are two other areas of study: acoustic phonetics, which aims to understand the physical properties of speech as sound waves in the environment, and auditory phonetics, which investigates how the ear perceives speech sounds.

2. Consonants:

Consonants are sounds made when the air flow is obstructed when it leaves the mouth.

Consonants’ articulation can be expressed using 3 features: voicing, manner of articulation, and place of articulation.

3. Voiced and Voiceless Sound:

Voiceless sounds occur when the vocal folds are apart, allowing air from the lungs to pass between them unobstructed. This results in sound production without vibration.

Voiced sounds, on the other hand, happen when the vocal folds come together, causing the air from the lungs to repeatedly push them apart as it pass through, creating a vibrating effect and producing sound.

4. Place Of Articulation:

This is where sounds are formed. The mouth contains numerous places of articulation, and consonants are identified using terms based on these places (e.g., lips for bilabials). The phonetic symbols representing consonants may resemble or differ from each other ([f] for "f," [v] for "v," or [ʃ] for "sh," [θ] for "th"). Sometimes, the transcription differs entirely from the word's spelling (e.g., "choir" transcribed as ˈkwaɪə).

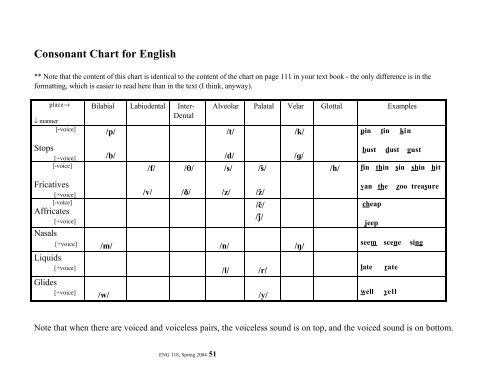

5. Manner Of Articulation And A Consonant Chart:

This concerns the pronunciation of consonants. Despite both [t] and [s] being voiceless alveolar sounds, they differ in their articulation: the [t] sound is classified as a "plosive" consonant, while the [s] sound is categorized as a fricative. A helpful resource for displaying information on commonly used consonants is a consonant chart, akin to the one depicted below:

6. Vowels:

Vowels differ from consonants in that they are produced with an unimpeded airflow and are usually voiced. The movement of the tongue controlling the airflow generates vowel sounds.

When discussing the articulation of vowels, we commonly distinguish between the front and back, or the high and low regions within our mouths. For example, in words like "heat" and "hit," the vowels are labeled as "high, front," indicating that they are formed with the front part of the tongue raised.

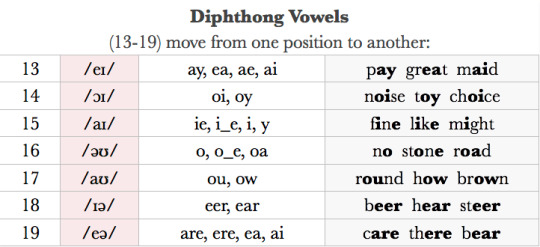

7. Diphthongs:

In addition to single vowel sounds, humans have developed diphthongs, which are combinations of two vowels. A diphthong is formed when our vocal tracts transition from one position to another, such as moving from [a] to [ʊ] to produce the sound [aʊ].

8. Subtle Individual Variation:

Vowel sounds can vary due to different accents, resulting in certain words sounding similar. However, individuals often possess an innate ability to distinguish these differences, a skill involving phonology, which encompasses the overall sound patterns of a language.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Reading and Reflection 3

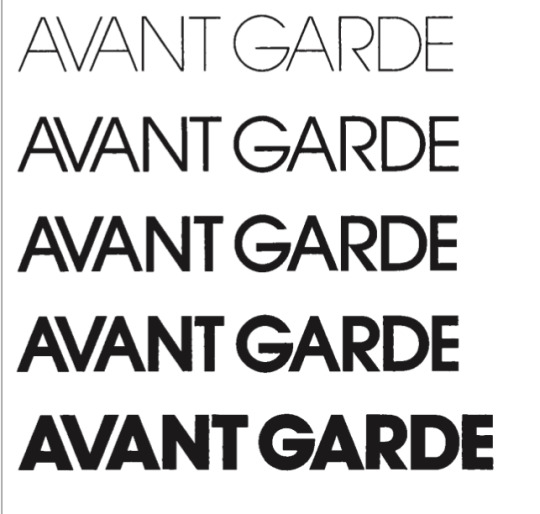

Anatomy of Type

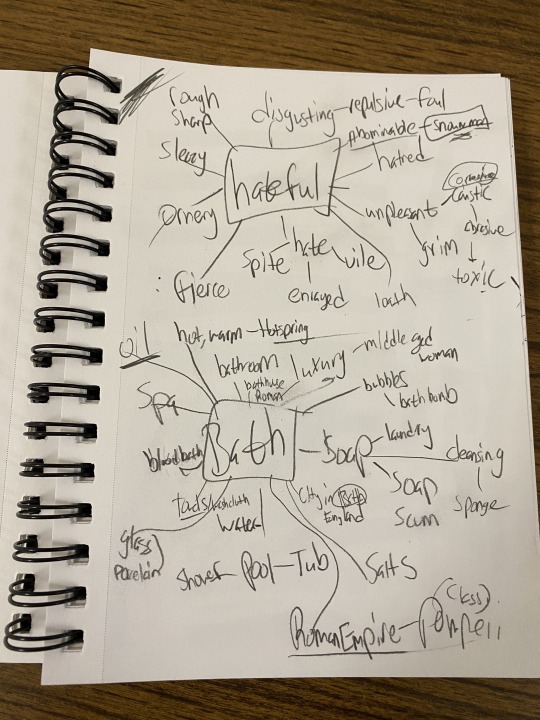

This chapter details all of the elements that make up a letterform. It was interesting to learn about the specific reasons why certain classifications of typography exist. Much of the the history of typography is hinged on the available technology of the time. So for a while, type was not as standardized and may have needed some jimmy rigging. Which I'm sure required a different sort of skill and intelligent, hands-on troubleshooting. I learned a few new words here and there. One I've never heard was Digraphs, which refer to diphthongs, and the term Oblique. Which I have seen, but I did not know there was a clear distinction between oblique and italics. Referring to oblique as a "posture" rather than simply a slight change of the typeface itself (italics). Which are styled to resemble handwriting (in most cases) and save room. The image below was from the section on line weights. I appreciated this one because of the simplicity there is very little change of the letter forms as the weight increases. Which I feel is a problem for many typefaces because they can end up looking completely different.

This project has a very intriguing starting point. I tend to take things very literally and at face value (it saves me from the mental gymnastics and overthinking). Using this method was an interesting way to coax out an idea. My two words were “hateful” and “bath(s)”. My genuine first thought (before I began writing) referred to, Hate>Racism and Pool. After the end of Jim Crow and around when desegregation laws were passed, many public pools were shut down. Because they’d rather have no pool, then swim with Black people. However, that was a little too heavy and difficult to connect to a brand/logo. So I quickly moved on to my other choices. After discussing it in class I think I may continue with the Roman Empire Idea. Mostly because I will already have some research to pull from. I would like to connect the theater possibly or just the Roman baths in general. I may also still play around with some type of cleaning agent.

0 notes

Text

Readerly Response #2

Due date of assigned reading: October 23, 2023

Title of assigned course reading: Mesmer (2019), "Introduction"

Mesmer (2019), Chapter 1, "Know the Code: Teacher's Reference on How English Works"

Big Takeaways:

Introduction: Through phonics instruction, children should understand how words work through the discovery of letters and how they work independently as well as combined to achieve meaningful comprehension and composition.

Chapter 1: The English system of writing is complicated as it is a deep orthography and teachers must understand how it works to effectively teach the different sounds, blends, and digraphs that make up the English language.

Nuggets:

Introduction: The quote "phonics instruction gives children the information about how letter sounds work so that they can build automatic work recognition that frees their conscious attention to concentrate on meaning" is literally so good/spot on. As fluent/proficient readers, decoding is not part of our reading experience anymore because we read words by sight. Because of that, we forget that children and young learners aren't there yet. As teachers, we have to instruct our students how to decode but then also, how to put meaning behind the words we are decoding.

Chapter 1: I like the discussion about the difference between oral language and written language. The way we speak differs from the way we write which can confuse students as they learn how to write. Speech operates differently than written language and how we speak does not flow in the same way we write. Again, as teachers, this is an important factor to consider as we teach writing.

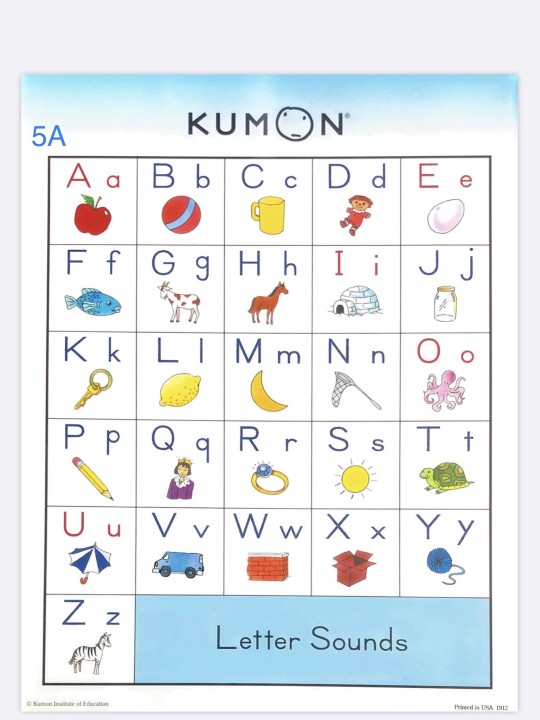

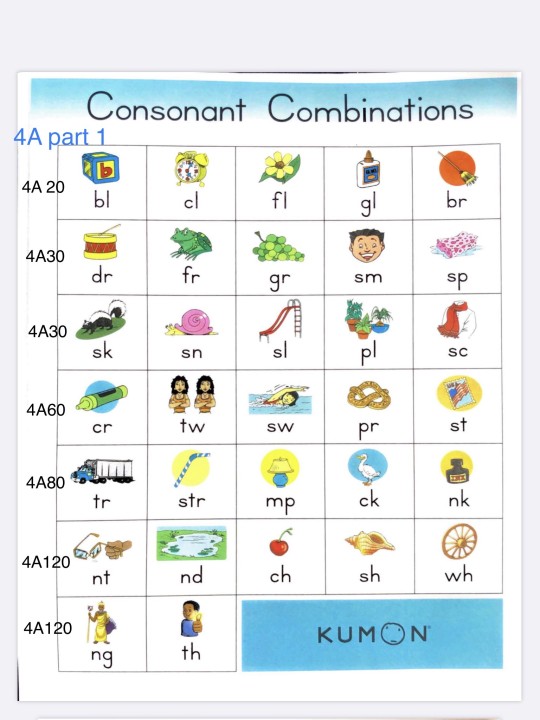

Readerly Exploration:

For this readerly exploration, I read this text deeply and reflected on how it related to me. During my four years of high school, I worked at an educational center where I worked with 3-, 4-, and 5-year-old students to learn how to read and write. In the thirty minutes I had with them, we would complete our worksheet but then depending on the level they were on, I would teach them new sounds and/or go over their sounds to review and practice them. This chapter (chapter 1) goes over all the sounds that I would teach my students. I loved this chapter because I knew all these different sounds, like the single consonants, consonant blends, and vowel sounds. But I didn't know the names of the sounds. Even though I taught my students diphthongs, I didn't know that was what those sounds were called. Same thing with the consonant digraphs. It was informative to read about because it is important to know about all these sounds especially when teaching young children, because the English language is confusing, and understanding all the different sounds and exceptions to the letter sounds is beneficial. I did not realize how much working at that center would benefit me and prepare me as a future educator.

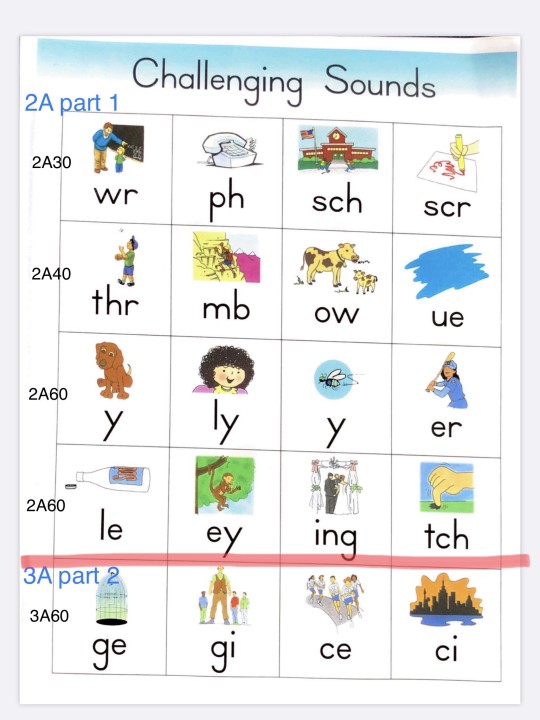

These are the charts I would use to teach and go over the sounds with my students (I thought I had physical copies of these but could not find them at my house):

1 note

·

View note

Text

Poll Conlang: Diphthongs

Last post ^

So, 7 vowels. Might write epsilon and open o as è and ò for the time being.

I think the most straightforward next step is to decide our diphthongs. Then we discuss feature bleed and that would likely decide our dorsals. Then we go into phonotactics and do spot shifts.

Diphthongs have a number of analyses that also lead to different interpretations between languages.

I'm kind of making this up as I go along but

Segments can be assigned either to an Onset or a Nucleus. Each ON pair gets assigned a unit of time in the language (a mora; but ON pairs are themselves often called moras). These are paired into feet, which are organized into words and phrases, with syllables appearing in the analysis as a secondary effect of sonority patterns.

ON pairs can appear without Onsets for ONØN feet; these often look like CVV syllables. A language can also have OØ ONs, which fuse according to sonority to build ONO or OON... syllables, what look like CVC or CCV... syllables.

So then you can theoretically distinguish vowel sequences (kei < underlying ke Øi) from "true diphthongs" that force two segments into the moraic space of one (e.g. kei having the same length as ka or kēi having the same length as kā).

One can also argue that the "true diphthong" type actually has an inner structure like a foot.

A trochee is a foot with initial emphasis, and tends to weigh every segment equally. This also appears to be the natural way humans tend to group rhythms given evidence from musicology.

An iamb is a foot with final emphasis, and tends favor weighing the final twice as long as the initial. Languages with iambs are more likely to distinguish long vowels from short and do a lot of other things.

The mini-feet a diphthong can be in however doesn't have to be the same as the "big" feet under the word-level.

But by thinking of it like this, we can explain to major types of diphthongs: opening and closing.

As close vowels are less sonorant and more consonant like, they tend to have less of the weight assigned from the mora. So an opening diphthong has properties associated with iambic feet, while closing diphthongs (more common overall) have properties like trochaic diphthongs.

I feel like I should mention right now that Spanish has trochaic feet but iambic diphthongs. ie and ue are almost more like je and we. But the stress generally follows a right-aligned trochaic pattern.

Another type of diphthong is height-harmonized. I've only really heard of it in the history of English, though, and underneath it seems to be a trochaic system undergoing monophthongization.

And of course, many languages contain both kinds of diphthongs, often due to some consonant being phonetically an open vowel (e.g. German's r) or just due to history giving both types (e.g. many SEA tonal languages get both in the process of reducing codas).

So I think four options for now

0 notes

Text

Hello I still exist! I’m just existing in…not-tumblr spaces right now. I’m doing both my job and covering a leave, so work is crazy. I’m also in the midst of tech week, aka Hell Week, for the musical I was hired to play violin for (which is brutal, but also super fun!) I’ve been prioritizing things like sleep and making real food over writing, and that probably won’t change a ton in the immediate future.

To all the wonderful people tagging me in stuff, I see you, and I love you, and I will actually go through everything at some point. That point might be summer, but I will get there!

#diphthong discusses#personal#update post#and by update i mean it#ocurred to me to post something in the five minutes before I put my phone down for bed#so this is the best you’re getting for now lol

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

nobody cares about this but i just gotta say it somewhere so i can fucking fall asleep already because it’s 03.22am

i’ve been working like a beast to try and finish off the exams and tasks that must be completed before i can get student loan again, found out monday that i’m missing a meekly 1,5 credits to get my next loan and if i don’t get it in this week then the first cheque of the term is obliterated into thin air never to be seen again, because you have 4 weeks from when the semester starts to accomplish your credits and if you haven’t done it in those four weeks then you don’t get any loan for that period and can’t get any until the week after your grades have been reported

it’s.. it sure is a system but hey some of that money is just free money that i get for being a student and i never have to pay that back so like. obviously i want the free money, along with the loan so i can pay bills and y’know. live a little

these credits are from a class in english that i took last term but i barely passed half the credits and now it’s a race to amend them. which isn’t all that easy because you can’t amend your credits whenever you feel like it, just in the spaces of the re-exam period (which thank god is still ongoing) but even so teachers at uni here usually have a three week grading period. and i have three days. until i can say bye bye to a lot of money.

so up until monday and including half of monday i thought i “just” had to do a 1000 word essay on a short story, THEN i was made aware that i had to do the essay and read two novels and answer questions about those, none of which i’ve read yet. one of them doesn’t even exist in libraries so i’d have to literally purchase it and that’s just not on my agenda right now

realising that i had slim to no chance at being able to manage that, i checked to see if i could finish another task or exam instead, and yes i could do a powerpoint oral presentation on a chosen accent and talk about phonemes and phonetic assimilation and elision and vowels and a brief history of the country and i was uhh fuck but okay. so that’s what i spent monday evening and all of today tuesday doing. i didn’t even have breakfast until 5pm when i was done and had sent the whole thing in for grading

however the person grading that turned out to be another person than who was gonna grade the essay and the novel questions, and that person has been really helpful when i’ve emailed her and told me to let her know when i’d handed in the essay and she’d have a look at it right away. that obviously doesn’t mean i’d get a pass but it’s at least nice to know there are teachers that try to be helpful

the other teacher that i ended up emailing today to explain my situation to (i need to get 1,5 credits by friday ideally, what can i do, i know it’s unreasonable to ask but can i let you know when i’ve submitted the presentation so you can have a look at it asap?) ended up feeling much less forthcoming and even though i finished the presentation and submitted it i’m not entirely sure i’ll get a pass on it. i hope so, but the other classmates had more thorough presentations where they had more examples of all sorts of things, diphthongs and connected speech and h-dropping and consonant phonemes and while i guess my pres was okay, it wasn’t as thorough as some of the others (we had to watch each other’s and give feedback on them).

so at the end of the evening i ended up going back to start on the 1000 word essay even though i realised there’s no way i’ll be able to get it all done, not to mention i have a 700 word essay to be done by thursday for the class i’m currently taking because thats gonna be discussed in a study group with my classmates so it can’t be a rough draft, it has to be actually finished

but then i remembered. the teacher who was forthcoming told me already a month ago when i brought it up that i needed to amend my credits, that i could do an oral presentation for more credits than what i’m currently lacking

and that presentation is different to the one i finished today, which actually had to be semi-decent and thorough

this other presentation, all i have to do is read a short story and then do a 5 minute oral presentation about what it’s about and what the underlying themes are and what the protagonist is going through

it doesn’t have to be formal or academic and i don’t have add citations with referencing and have a thesis statement and make sure my lines are indented and god knows what else all the things you have to have in an essay, and that’s not even counting the words and for it to make sense and be decent

i just have to yabber on about a short story for 5 mins while i record my screen and yabadabadoo i’m fucking good to go my maties. it’ll probably take me longer to actually put together the presentation than anything else, powerpoint and me are not friends but ah, i am feeling really positive that i can get a grade if not tomorrow then at least thursday because like shawn said: i can only fail up, with this

literally legend. anyway that’s everything i had to get out of me.

fingers crossed i get not one but two grades by thursday at the latest, because i need those credits regardless but extra much right now

and the story i gotta read that i’ve chosen is the purple elephant?? was it? by orwell?

anyway that’s all peeps, thank you and goodnight

0 notes

Text

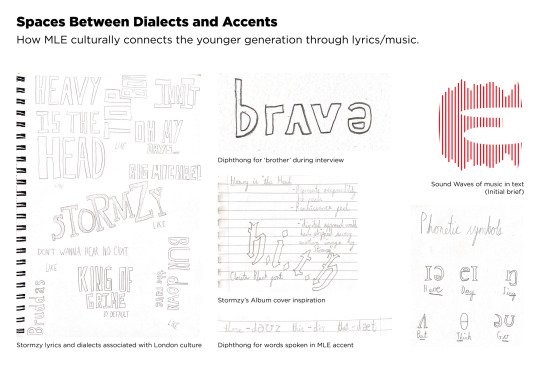

Pinup Critique (02/11/22) (Self-Reflection) - ISTD Project

For this studio day I had to present my initial experiments. In my presentation I explained what brief I was doing, the subject area I have chosen, discuss the generated ideas I had produced and where I found the inspiration, and what my next steps are during this process.

Firstly I clarified to my peers and tutors that I transferred to a different brief, from ‘Mapping the World’ to ‘Spaces Between,’ because I was finding it difficult to “map” British accents when there’s regions that are mixed with different dialects and language. As a result, I am now focusing on spaces between dialects and accents.

On my A3 pinup sheet I displayed my sketches of lyrics and dialects that Stormzy uses in his lyrics. The idea was to shout the MLE dialects to portray the busyness of London as an urban area. Additionally, I had sketches of diphthongs that pronounce certain dialects within the language. I also included one of my first experiments from the previous brief.

The feedback was very helpful in terms of providing support from both my tutors and my peers. I needed help with initiating visual ideas for my concept, and so I received a few responses in regards to what I need to do next in this project. I was advised to consider the diversity in culture and how it associates with the younger generation from different ethnic backgrounds. In addition, one experiment I can explore involves diphthong symbols and clearly showing how to read the accent. Then, one of my tutors suggested that I focus on one word, which will allow me to conduct some primary research into people’s perspectives on dialects and accents in MLE.

Overall I am satisfied with the feedback I received in regards to how I approach the brief. I need to generate more ideas quickly in order to make decisions for my final solution. Furthermore, I must explore different materials that are relevant to how I produce a creative solution that suits my target audience.

0 notes

Text

Supplement: A Simple Guide to Matoric Pronunciation

The material in this post is intended to be supplemental to materials on the Matoran Language (“Matoric”), which are presented in this post. In particular, this material replicates and expands on the guide to pronunciation found in the Introduction to the Matoran Language.

The document linked below (a view-only Google Doc) describes how to pronounce the (most prevalent dialectal variant of the) Matoran Language (“North Matoric”, the dialect of Metru Nui), presented for speakers of English.

Link: A Simple Guide to the Pronunciation of the Matoran Language

The first section in the document discusses the Matoran spelling system (the romanized version of it, that is) and how each letter corresponds to specific sounds, covering consonants and vowels/diphthongs. The second section deals with stress or emphasis in Matoran words.

If you ever needed more details about how precisely to pronounce the weird and strange words and syllables that make up the Matoran Language, this is the resource for you! Enjoy.

#bionicle#matoran language#matoric#conlanging#matoran dictionary#3rd edition#3e#pronunciation#spelling#orthography#phonology#stress#emphasis#prosody#sound system#phonetics#reference

290 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here’s something I don’t get: the traditional view of Gothic has three values for the diphthongs written ai and au, as short and long monophthongs and a true diphthong respectively, mostly based on etymological arguments from comparison to other Germanic languages, and what values would have been inherited from Proto-Germanic. These digraphs definitely represented monophthongs in at least some places, but some scholars go so far as to argue they only represented monophthongs. The evidence is complicated and unclear--Gothic was spoken across centuries and in various times from the Dnieper to Spain--but one line of evidence includes spellings of Greek names and loanwords like Pawlus and aiwxaristia, where w stands for Greek upsilon. Why (you might argue) would au be pronounced as a diphthong in some Gothic words, but aw be used to write that same diphthong in Greek, if these values are the same?

But they aren’t the same! AFAICT Greek began to move away from the [u] offglide that upsilon represents in those digraphs quite early--well before, in fact, the Gothic Bible was composed. It’s true that early Koine Greek had those diphthongs, but later Koine Greek seems not to have. The w in those loanwords likely corresponds to a labial fricative (a sound for which Gothic had no exact letter, but for which w would be quite suitable), and not to the second element of a diphthong. So it would make sense to spell those two sounds differently, as they were in fact different! There’s still ambiguity there--is w consonantal always or did Gothic have [y] that is sometimes spelled with w, which dialects ultimately monophthongized those diphthongs everywhere and from when, etc.--but none of the resources I’ve encountered on Gothic, when discussing the values of au, mention the fact that the Greek speakers from whom the Goths borrowed their alphabet might not have had that diphthong at all.

13 notes

·

View notes