#ivan illich

Quote

The term ‘shadow work’ was coined by Ivan Illich in connection with new findings in women’s studies at the end of the 1970s. Illich included in this category all those activities needed to survive on a monetary income in a modern market society. By this, he did not mean use-value-creating subsistence activities – the material basis of which was steadily eroding in industrial society – but rather activities like shopping, queuing, waiting, comparing prices, and visits to the bank, court or other state authorities and welfare bodies. This ‘drudgery in industrial society’ is the flip side of work and of its necessary corollary, surviving on a monetary income, and is carried out predominantly (albeit not exclusively) by women. Commonly, neither the people engaged in these activities nor observers perceive this as work as such. Shadow work creates neither use value nor exchange value and thus appears to belong to a different category of human activity. Illich, however, located these activities squarely within the sphere of securing one’s survival and thus linked them intimately with paid labour.

Andrea Komlosy, Work: The Last 1,000 Years

691 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ivan Illich out here just casually dropping paragraphs like this

#Ivan illich#I’ve only read 1/4 of one paper but you know what? I’m a fan#colonialism cw#white supremacy culture cw#image#undescribed#someone remind me to transcribe when I’m not on mobile

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

A radical monopoly goes deeper than that of any one corporation or any one government. It can take many forms. When cities are built around vehicles, they devalue human feet; when schools preempt learning, they devalue the autodidact; when hospitals draft all those who are in critical condition, they impose on society a new form of dying. Ordinary monopolies corner the market; radical monopolies disable people from doing or making things on their own. The commercial monopoly restricts the flow of commodities; the more insidious social monopoly paralyzes the output of nonmarketable use-values. Radical monopolies . . . impose a society-wide substitution of commodities for use-values by reshaping the milieu and by “appropriating” those of its general characteristics which have enabled people so far to cope on their own.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In the case of car culture, the problems of sprawl and automobile dependency did not inevitably result from the automobile itself, but from the power interests that redesigned society around it. The problem was created by subsidies to monoculture development, freeways systems imposed by eminent domain, and legal prohibitions — like zoning — against mixed-use development.

Before the rise of car culture and car-centered urban design, the norm was the compact, mixed-use city or town where residences were within foot, bicycle, bus or streetcar distance of the downtown district where people worked or shopped. Increased population was accommodated primarily by modular proliferation — e.g. the railroad suburb — rather than outward sprawl.

Absent the imposition of car culture by the federal and local governments and by the local real estate industry, the automobile would have served a useful niche function in cities laid out in the old fashion. Its primary market would have been people like farmers in the areas outside cities, where population concentrations were insufficient to be served by streetcar or rail lines. For periodic trips into town and back, perhaps in a small truck capable of conveying a load of vegetables to the farmers’ market or bringing home groceries and dry goods, a light internal combustion engine or electric motor would have been sufficient. With no need for rapid acceleration on the freeway, there would be no point for heavy engine blocks with six cylinders, and the overall weight of the vehicle could be reduced accordingly. With flat body panels capable of being produced on a cutting table, there would have been no need for Detroit’s two- or three-story stamping presses. The automobile industry would have been an affair of hundreds of local factories.

Hence it is not true that “[p]ast a certain threshold of energy consumption, the transportation industry dictates the configuration of social space.” Rather, the configuration of social space dictates the forms of transportation adopted, which dictates the level of energy consumption.

Illich’s tendency to see the proliferation of managerial bureaucracies and their unwilling clienteles as an expansionary phenomenon in its own right with no need for a causal explanation, rather than a secondary effect of larger class and power interests, is also illustrated in his treatment of squatters.

Both the non-modernized and the post-modern oppose society’s ban on spatial self-assertion, and will have to reckon with the police intervening against the nuisance they create. They will be branded as intruders, illegal occupants, anarchists and nuisances, depending on the circumstance under which they assert their liberty to dwell: as Indians who break in and settle on fallow land in Lima; as favellados in Rio de Janeiro, who return to squat on the hillside from which they have just been driven — after 40 years’ occupancy — by the police; as students who dare to convert ruins in Berlin’s Kreuzberg into their dwelling; as Puerto Ricans who force their way back into the walled-up and burnt buildings of the South Bronx. They will all be removed, not so much because of the damage they do to the owner of the site, or because they threaten the health or peace of their neighbors, but because of the challenge to the social axiom that defines a citizen as a unit in need of a standard garage. [emphasis added]

Both the Indian tribe that moves down from the Andes into the suburbs of Lima and the Chicago neighborhood council that unplugs itself from the city housing authority challenge the now-prevalent model of the citizen as homo castrensis, billeted man.

Illich’s framing of this as some inherent expansionary logic or hegemonic drive inherent in the “managerial-professional classes” themselves, and not the outcome of a much larger, long-term process of land privatization and enclosure driven by capitalist class interests, is a major critical failure."

-Kevin Carson, ”The Thought of Ivan Illich: A Libertarian Analysis“

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

L'urgenza di salvare l'umanità è quasi sempre il dito dietro cui si nasconde l'urgenza di dominare l'umanità. Quindi, come regola generale, salva prima le persone vicine a te. Inizia con te stesso.

Ivan Illich, Tools for Conviviality, 1973

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Healthy people are those who live in healthy homes on a healthy diet; in an environment equally fit for birth, growth work, healing, and dying… Healthy people need no bureaucratic interference to mate, give birth, share the human condition and die.

— Ivan Illich

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

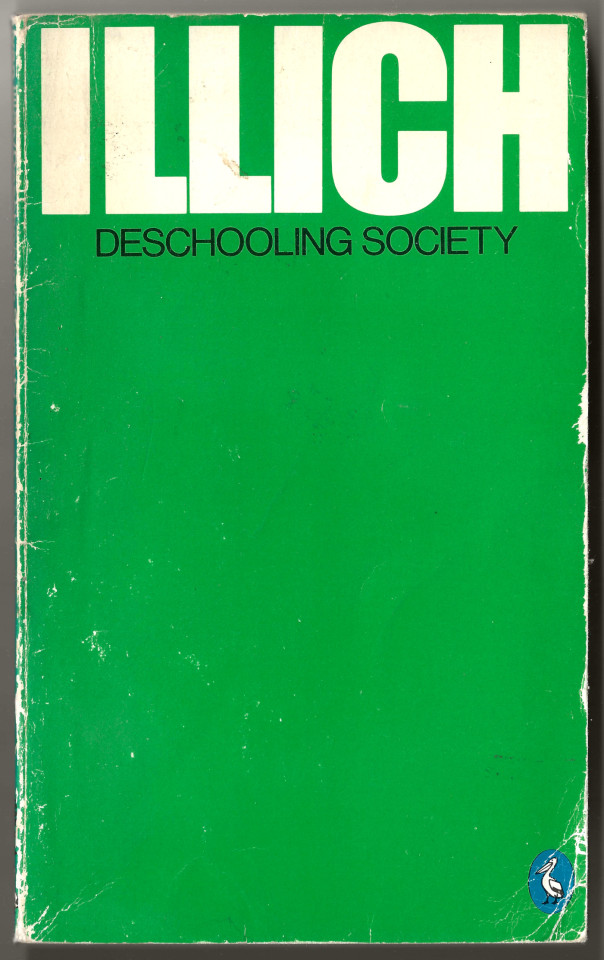

School is the advertising agency which makes you believe that you need the society as it is.

- Ivan Illich, Deschooling Society

#q#quotes#ivan illich#deschooling society#unschooling#mindful consumption#mindful living#mindfulness#advertising#propaganda#sidewalkchemistry

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deschooling Society by Ivan Illich with a cover design by David Pelham.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“E se na verdade toda minha vida tiver sido errada?”.

— A Morte de Ivan Ilitch

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

And he has to live like this on the edge of destruction, alone, with nobody at all to understand or pity him.

Leo Tolstoy, The death of Ivan Ilych

#leo tolstoy#lev tolstói#tolstoi#russian#russian literature#classical literature#ivan illich#fiodor dostoievski#fiodor dostojewski#books & libraries#letters#literature#art#writers#rory gilmore

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

The choice for or against [economic growth as a primary value] decides whether

unemployment, that is, the effective liberty to work free from wages and/or salary,

shall be viewed as sad and a curse, or as useful and a right.

— Ivan Illich [x] (emphasis mine)

Hot damn, Mr. Illich out here 40 years ago dropping takes from 3024

#Ubi#universal basic income#universal basic services#quote#ivan illich#I’ve only read like 3 pages but I’m already a huge fan#still waiting to find out how this relates to linguistics tho

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Ivan Illich was an idiosyncratic revolutionary. Fundamentally, most radical critics object that our institutions unfairly allocate good and services—education, health care, housing, transportation, consumer goods—or jobs, or respect, or, simply, money. Illich nicely summarized the left’s perennial program as “more jobs, equal pay for equal jobs, and more pay for every job.” For Illich, these demands were beside the point. He thought that, by and large, the goods, services, jobs, and rights on offer in every modern society were not worth a damn to begin with. In fact, he thought they, and the way of life they constituted, were toxic. He was not a reactionary in any useful sense of that term, but he was a fervent anti-progressive.

(…)

In a series of subsequent books—Tools for Conviviality (1973), Energy and Equity (1974), Medical Nemesis (1975), Toward a History of Needs (1978), The Right to Useful Unemployment (1978), and Shadow Work (1981)—Illich formulated parallel critiques of medicine, transportation, law, psychotherapy, the media, and other preserves of self-perpetuating expertise. The medical system produces patients; the legal system produces clients; the entertainment system produces audiences; and the transportation system produces commuters (whose average speed across a city, he liked to point out, is less than the average speed of pedestrians or bicyclists—or would be, if walking or bicycling those routes hadn’t been made impossible by the construction of highways). In this process, far more important than merely teaching us behavior is the way these systems teach us how to define our needs. “As production costs decrease in rich nations, there is an increasing concentration of both capital and labor in the vast enterprise of equipping man for disciplined consumption.”

Why do we have to be taught to need or disciplined to consume? Because being schooled, transported, entertained, etc.—consuming a service dispensed by someone licensed to provide it—is a radical novelty in the life of humankind. Until the advent of modernity only a century or two ago (in most of the world, that is; longer in “advanced” regions), the default settings of human nature included autonomy, mutuality, locality, immediacy, and satiety. Rather than being compulsorily enrolled in age-specific and otherwise highly differentiated institutions, one discovered interests, pursued them, and found others (or not) to learn with and from. Sick care was home- and family-based, far less rigorous and intrusive, and suffering and death were regarded as contingencies to be endured rather than pathologies to be stamped out. Culture and entertainment were less abundant and variegated but more participatory. The (commercially convenient) idea that human needs and wants could expand without limit, that self-creation was an endless project, had not yet been discovered.

(…)

But these defects were reformable; more intractable was “cultural iatrogenesis”—the destruction of “the potential of people to deal with their human weakness, vulnerability, and uniqueness in a personal and autonomous way.” (…)

The notion of “radical monopoly” plays an important role in Illich’s critique of professionalism:

A radical monopoly goes deeper than that of any one corporation or any one government. It can take many forms. When cities are built around vehicles, they devalue human feet; when schools preempt learning, they devalue the autodidact; when hospitals draft all those who are in critical condition, they impose on society a new form of dying. Ordinary monopolies corner the market; radical monopolies disable people from doing or making things on their own. The commercial monopoly restricts the flow of commodities; the more insidious social monopoly paralyzes the output of nonmarketable use-values. Radical monopolies . . . impose a society-wide substitution of commodities for use-values by reshaping the milieu and by “appropriating” those of its general characteristics which have enabled people so far to cope on their own.

Professions colonize our imaginations; or as Michel Foucault (whom Illich’s language sometimes recalls—or anticipates) might have said, they reduce us to terms in a discourse whose sovereignty we have no idea how to contest or criticize.

Unlike Foucault, who sometimes seemed to take a grim satisfaction in demonstrating how cunningly we were imprisoned in our language and institutions, Illich was an unashamed humanist. His ties to the barrios and campesinos of North and South America were deep and abiding. His “preferential option for the poor” (the slogan of Catholic liberation theology) was a peculiar one: he hoped to save them from economic development at the hands of Western-trained technocrats. Illich had hard words for even the best Western intentions toward the Third World. (It is possible that what annoyed the CIA was Illich’s advice to the Peace Corps volunteers who came to Cuernavaca for Spanish-language instruction that they should leave Latin American peasants alone, or perhaps even try to learn from them how to de-develop their own societies.) Religious and ecological radicals, however generous and respectful, still wanted to bring the poor a poisoned gift, in Illich’s judgment:

Development has had the same effect in all societies: everyone has been enmeshed in a new web of dependence on commodities that flow out of the same kind of machines, factories, clinics, television studios, think tanks. . . . Even those who do worry about the loss of cultural and genetic variety, or about the multiplication of long-impact isotopes, do not advert to the irreversible depletion of skills, stories, and senses of form. And this progressive substitution of industrial goods and services for useful but nonmarketable values has been the shared goal of political factions and regimes otherwise violently opposed to one another.

Illich might have said more about those fugitive “stories, skills, and senses of form”; he might have tried harder to sketch in the details of a society based on “nonmarketable values.” But in Tools for Conviviality and elsewhere, he at least dropped hints. He certainly did not idealize the primitive—he might have welcomed the term “appropriate technology” if he had encountered it. He enthused over bicycles and the slow trucks and vans that moved people and livestock over the back roads of Latin America before the latter were “improved” into useless and dangerous highways. He was a connoisseur of the hand-built structures cobbled together from cast-off materials in the favelas and slums of the global South. He thought phone trees and computer databases that would match learners and teachers were a very plausible substitute for the present educational system. He thought the Chinese “barefoot doctors” were a promising, though fragile, experiment. He was friendly to any gadget or technique or practice—he called them “convivial” tools—that encouraged initiative and self-reliance rather than smothering those qualities by requiring mass production, certified expertise, or professional supervision.

Illich proposed “a new kind of modern tool kit”—not devised by planners but worked out through a kind of society-wide consultation that he called “politics,” undoubtedly recognizing that it bore no relation to what currently goes by that name. The purpose of this process was to frame a conception of the good life that would “serve as a framework for evaluating man’s relation to his tools.” Essential to any feasible conception, Illich assumed, was identifying a “natural scale” for life’s main dimensions. “When an enterprise [or an institution] grows beyond a certain point on this scale, it first frustrates the end for which it was originally designed, and then rapidly becomes a threat to society itself.”

A livable society, Illich argued, must rest on an “ethic of austerity.” Of course, he didn’t mean by “austerity” the deprivation imposed by central bankers for the sake of “financial stability” and rentier profits. Nor, though he rejected affluence as an ideal, did he mean asceticism. He meant “limits on the amount of instrumented [i.e., technical or institutional] power that anyone may claim, both for his own satisfaction and in the service of others.” Instead of global mass society, he envisioned “many distinct cultures . . . each modern and each emphasizing the dispersed use of modern tools.”

Under such protection against disabling affluence . . . tool ownership would lose much of its present power. If bicycles are owned here by the commune, there by the rider, nothing is changed about the essentially convivial nature of the bicycle as a tool. Such commodities would still be produced in large measure by industrial methods, but they would be seen and evaluated . . . as tools that permitted people to generate use-values in maintaining the subsistence of their respective communities.

Whether one calls this revolution or devolution, it clearly requires, he acknowledged, “a Copernican revolution in our perception of values.” But there was nothing quixotic or eccentric about it. On the contrary, this affirmation of limits aligns Illich with what is perhaps the most significant strain of social criticism in our time: the anti-modernist radicalism of Lewis Mumford, Christopher Lasch, and Wendell Berry, among others.

(…)

Criticism of this breadth and depth illuminates everything. Exactly how to turn it against everything is usually, as in this case, more than even the critic can say.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Standard monopoly, in the microeconomic sense, is when one firm in a market secures a dominant position in supplying a particular good. Radical monopoly, in contrast, is when an entire institutional complex makes the type of good itself artificially necessary in order to exist and crowds out alternatives. “Radical monopoly imposes compulsory consumption and thereby restricts personal autonomy. It constitutes a special kind of social control because it is enforced by means of the imposed consumption of a standard product that only large institutions can provide.”

I use the term “radical monopoly” to designate… the substitution of an industrial product or a professional service for a useful activity in which people engage or would like to engage. A radical monopoly paralyzes autonomous action in favor of professional deliveries.

The classic example of radical monopoly is car culture and its attendant urban sprawl.

Cars can thus monopolize traffic. They can shape a city into their image — practically ruling out locomotion on foot or by bicycle in Los Angeles…. That motor traffic curtails the right to walk, not that more people drive Chevies than Fords, constitutes radical monopoly…. [T]he radical monopoly cars establish is destructive in a special way. Cars create distance…. They drive wedges of highways into populated areas, and then extort tolls on the bridge over the remoteness between people that was manufactured for their sake. This monopoly over land turns space into car fodder. It destroys the environment for feet and bicycles.

…A radical monopoly paralyzes autonomous action in favor of professional deliveries. The more completely vehicles dislocate people, the more traffic managers will be needed, and the more powerless people will be to walk home.

Another example is how the institutional complex around the building industry — contracting firms, materials production, building codes, etc. — has reinforced its own power at the expense of convivial alternatives. Favelas and shantytowns — often displaying a high degree of craftsmanship and technical skill — exist on the outskirts of cities all over the Global South (Colin Ward has a considerable body of work on the tradition of self-built housing in the West, as well). It’s entirely feasible, technically, to produce construction materials conducive to self-built housing by amateurs. “Components for new houses and utilities could be made very cheaply and designed for self-assembly.” Not only do local building codes prohibit such construction as unsafe, but they also prohibit competitive pressure for even professional contracting firms to adopt cheaper, vernacular building techniques using locally sourced material, by codifying conventional methods into law.

The problem of radical monopoly is exacerbated by a shared institutional culture that can imagine no solution to the negative effects of radical monopoly but to intensify the scale of the monopoly. With entire sincerity, for the most part, the managerial elites in a given policy area which suffers from the pathologies of radical monopoly are conditioned to perceive as “extreme” any proposed solution that cannot be carried out within the existing institutional framework, by people like themselves. That is, “the institution has come to define the purpose.” The only cure for a managerial bureaucracy’s mismanagement is to give it more resources and control. The standard approach of a managerial bureaucracy is to “solve a crisis by escalation.” Reforms which are carried out within the framework of radical monopoly “escalate what they are meant to eliminate.”[31]

-Kevin Carson, "The Thought of Ivan Illich: A Libertarian Analysis"

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

«…not only all machines, but all other animals as well.»

5 notes

·

View notes