#kings and queens of castile

Text

La Reine Blanche de Castille et son fils Saint Louis

#Blanche de Castille#saint louis#st louis#louis ix#louis 9#roi de france#moi je dis roy de Franc#king of france#france#french history#aquarelle#watercolour art#art#queen of france#queen

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

CONSORTS OF ENGLAND SINCE THE NORMAN INVASION (2/5) ♚

Eleanor of Castile (November 1272 - November 1290)

Margaret of France (September 1299 - July 1307)

Isabella of France (May 1308 - January 1327)

Philippa of Hainault (January 1328 - August 1369)

Anne of Bohemia (January 1382 - June 1394)

Isabella of Valois (October 1396 - September 1399)

Joan of Navarre (February 1403 - March 1413)

Catherine of Valois (June 1420 - August 1422)

Margaret of Anjou (May 1445 - May 1471)

Elizabeth Woodville (May 1464 - April 1483)

#my photoset.#history#historyedit#history edit#plantagenets#lancaster#house of lancaster#house of york#elizabeth woodville#margaret of anjou#catherine of valois#the king netflix#the white queen#joan of navarre#isabella of valois#anne of bohemia#philippa of hainault#isabella of france#margaret of france#eleanor of castile#royalty#royals#medieval history#medieval queens#queen consorts#war of roses#english history#historical royals#consorts of england#consorts of england and britiain.

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leonor to Catherine of Aragon. House of Borbón to House of Trastámara.

#credits to the rightful owners#house of borbón#House of Trastámara#spanish royal family#princess leonor#king felipe vi#Juan carlos I#infante juan count of Barcelona#king Alfonso xiii#king alfonso xii#queen isabella ii of spain#king Ferdinand VII#Charles IV of Spain#Charles III of Spain#Philip V of Spain#Luis grand dauphin#Maria Theresa of Spain#Philip IV of Spain#Philip III of Spain#Philip II of Spain#Charles V of Spain#juana i of castile#catherine of aragon

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Margaret of Austria is Shipwrecked and King Henry VII of England Writes to Her at Southampton – 1497

Probably by Pieter van Coninxloo

Diptych: Philip the Handsome and Margaret of Austria

about 1493-5

https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/GROUP20

When King Charles VIII of France put into motion his plans to extend his power basis into Italy, he attacked Naples which belonged to the sphere of influence of King Ferdinand of Aragon. Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I concluded an anti-French…

View On WordPress

#Burgundian history#Charles V#Duke of Burgundy#Ferdinand#Henry VII#Holy Roman Emperor#Isabella#Juan Prince of Asturias#Juana of Castile#King of Aragon#King of England#Margaret of Austria#Maximilian I#medieval history#Philip the Handsome#Queen of Castile#Spanish history#Women’s history

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queen Joanna "the Mad" of Castile watching over the casket of her dead husband Philip I of Castile.

Francisco Pradilla, 1877

#entierro felipe ii#Philip the handsome#joanna the mad#juana la loca#castile#castilla#european art#dark#gloomy#catholic kings#catholic queen#catholocism#isabel la catolica#comuneros#rebelion de los comuneros#juan bravo#maldonado#maria pacheco#house of habsburg#habsburg monarchy#spain#charles I#charles V#carlos V#holy roman emperor#holy roman empire

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Spanish Princess#spanishprincessedit#Joanna Queen of Castile and Aragon#Prince Henry#Juana la Loca#Joanna the Mad#King Henry VIII#SPS1E6

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

"To all intents and purposes she may be counted among the kings of France"

The hour that struck the death of Louis VIII was arguably the most critical in the history of the Capetian family. The new king, one day to be St Louis, was still a child. The trend of events in the previous two reigns had brought the higher nobility to realise that its independence would soon be seriously threatened. But a unique opportunity was raised to the regency of the queen-mother, Blanche of Castile, on the pretext that she was a woman and a foreigner. Yet this was not the first occasion on which the king's widow had acted as regent, nor the first on which a queen had played a part in politics. Philip Augustus had been the first Capetian not to involve his wife in the government of his realm. Before his time the queens of France had often intervened in affairs of state. Constance of Arles, not content with making married life difficult for Robert the Pious, had wanted to change the order of succession to the throne. She had led the opposition to Henri I, provoking and upholding his brothers against him, and she was perhaps responsible for the separation of Burgundy from the royal domain, to which Robert the Pious had joined it. Anna of Kiev, after the death of her husband Henri I, had been one of the regents, and it was only her second marriage, to Raoul de Crépy, that took her out of politics. Bertrada de Montfort's influence over Philip I had been notorious, and so had her hostility to the heir to the throne, whom she had even been accused of trying to poison. Adelaide of Maurienne, despite a physical personality before which Count Baldwin III of Hainault is said to have recoiled, had held considerable sway over Louis VI, procuring the disgrace of the chancellor, Etienne de Garlande, and egging on Louis to the Flemish adventure from which her brother-in-law, William Clito, was to profit so much. Eleanor of Aquitaine- as St Bernard had complained- had more power than anyone else over Louis VII as long as their marriage lasted. Louis VII's third wife, Adela of Champagne, had appealed to the king of England for help against her son Philip Augustus when he had sought to free himself of the tutelage of her brothers of Champagne. Later, reconciled with Philip, Adela had been regent during his absence from France on crusade. From the beginnings of Capet rule, the queens of France had enjoyed substantial influence over their husbands and over royal policy.

But Blanche of Castile was to play a greater role than any of her predecessors. To all intents and purposes she may be counted among the kings of France. For from 1226 until her death in 1252 she governed the kingdom. Twice she was regent: from 1226 to 1234, while Louis IX was a minor, and from 1248 to 1252 during his first absence on crusade. Between 1234 and 1248 Blanche bore no official title, but her power was no less effective. Severe in personality, heroic in stature, this Spanish princess took control of the fortunes of the dynasty and the kingdom in outstandingly difficult circumstances. For in 1226 there arose the most redoubtable coalition of great barons which the House of Capet ever had to face. Loyalty to the crown, so constant a feature of the past, seemed to be in eclipse. This was at any rate true of the barons who revolted, for they appear to have tried to seize the person of the young king himself- an attempt without parallel in Capetian history.

Blanche of Castile threw herself energetically into the struggle over her son and his throne. Taking her father-in-law, Philip Augustus, as her model, she won over half her enemies by craft, vigorously gave battle to the rest, and enlisted the alliance of the Church, including the Pope himself, and of the burgess class, which in marked fashion took the side of the royal family. Blanche was able to fend off Henry III of England, who tried to take the opportunity of recovering his ancestral lands, lost by John to Philip Augustus. She broke up the baronial coalition and reduced to submission the most dangerous of the rebels, Peter Mauclerc, Count of Brittany, and Raymond VII, Count of Toulouse. She adroitly took advantage of her victory to re-establish- this time definitively- the royal power in the south of France: her son Alphonse was married to the daughter and heiress of Raymond of Toulouse. The way was now open for the union of all Raymond's rich patrimony with the royal domain.

The Capetian monarchy emerged all the stronger from a crisis which had threatened to overwhelm it. Blanche felt it her duty not to rest on her laurels. After her son came of age she continued to make herself responsible for good and stable government. By the force of her example she drove home the lessons which Philip Augustus seems to have wanted to press upon his grandson when they had talked together. To Blanche's initiative must be credited the measures taken to suppress the dangerous revolt of Trencavel in Languedoc, as also those taken to defeat the coalition broken up after the battle of Saintes. On these occasions Louis IX did no more than carry out his mother's policy. When he went off on crusade, Blanche one more officially shouldered the government of the kingdom. She maintained law and order, prevented the further outbreak of war with England, and successfully pressed on with the policy which was to lead to the annexation of Languedoc. Likewise it was she who refurnished her son's crusade with men and money, and she took all the steps necessary for the safety of the kingdom when Louis was captured in Egypt.

Robert Fawtier- The Capetian Kings of France- Monarchy and Nation (987-1328)

#xiii#robert fawtier#the capetian kings of france#blanche de castille#queens of france#regents#louis viii#louis ix#philippe ii#constance d'arles#robert ii#henri i#anne de kiev#philippe i#bertrade de montfort#adélaïde de savoie#louis vii#étienne de garlande#st bernard#aliénor d'aquitaine#adèle de champagne

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

the historical comparison games with henry viii are so taxing....i hate twitter, lmfao

#i am not going defend any of the heinous and hell-deserving things he did but i am really not about pretending like comparatively his#successors and predecessors were morally superior ; or at least not by very much?#and YES even if we limit it to queens/kings of england#for fuck's sake; george i of england ordered the murder of his wife's lover#and was drowned with heavy stones#he then proceeded to divorce and arrest his former wife#she was never again allowed to see any of her children#and imprisoned her for the rest of her life#if life imprisonment is much better than judicial murder like...idt it is by very much?#and permanent child separation#even if the prisons are estates rather than cells. like. especially when we are talking about 30+ years#and i think this about juana of castile too#also the sons of francis i WERE actually kept in dank cells by charles v .#and they were CHILDREN??

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm actually quite proud of Armand right now. Openly admitting to Amalia the reason their relationship was always strained was because he'd always been jealous of her and her relationship with their father is such a great character moment for him.

One thing season 4 is definitely delivering is some much needed depth and exploration of the Sadida Royal family. And I find myself fascinated (not only because Amalia is my favourite character and I have a soft spot for her people).

Personally, Armand is a character I have a lot of trouble having a clear stance on. I don't hate him, and it's true his motives become clear and even understandable once you give them some thought, it's just that Ankama does a wonderful job at making him both outwardly dislikable given his abrasive personality and some of his most questionable actions.

For example, season 3 Armand and season 4 Armand are almost like night and day. Maybe it is indeed that his new role as king has forced him to be more responsible and emotionally mature, but the vibes between L'assamblée and Falling Down are completely different.

In season 3 he just oozed contempt for his sister, and his actions towards her reeked of ulterior motives. The fact that Aurora has been described as manipulative (even her hairstyle is meant to hint at her true nature) and was purposely placed in between the two siblings as a visual nod to how she's keeping them apart doesn't help matters.

Which is another factor to take into account: Aurora's character and the role she plays in the siblings' deteriorating bond.

Even if so far she seems to genuinely love Armand, I really can't bring myself to trust Aurora. Not only because of all the behind-the-scenes facts I already mentioned, but because her actions are just sketchy and clearly veered to the betterment of the Osamodas rather than the Sadida.

First of all, her contempt for Amalia is genuine and she legitimately seems to be planning to send her away to keep her from interfering with her plans. After all, this is literally what she had to say about her sister-in-law:

"Ne vous en faîtes pas mon prince, nous finirons bien par redresser cette mauvaise herbe."

Translation: "Don't worry, my prince, we'll get this weed straightened out in the end."

(I haven't watched the English dub, so my apologies if the translation doesn't match the official version).

There's also the fact that, despite being the new Sadida Queen, her intentions in season 3 clearly laid in the benefit of her own kingdom, the Osamodas. Such is reflected in her choice of suitors for Amalia:

She intended for Amalia to marry Ashdur, her own cousin, thus, strengthening the Osamodas' hold over Sadida politics. In fact, it becomes quite clear Aurora's choice in suitors, only supported by Amalia implying back then her sister-in-law had already tried the same thing with her brothers, was much less about the future of the Sadida Kingdom and more about the Osamodas' sake.

After all, while arranged marriages between royal families isn't anything new, usually the sensible and even most strategic thing to do is for rulers to"spread" their children and marry them into different families around the world. That is exactly what Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabela of Castile did with their own children, they married them off to the royal families of England, Portugal, and Austria.

With that in mind, having both Sheran Sharm children marry Osamodas royalty just seems dumb, doesn't it? It all comes to show Aurora is more concerned over solidifying her power over the Sadida Kingdom than its actual well-being.

Which is why I'm still going to keep my guard up regarding her character until the season ends. After all, we still have 9 more episodes where everything can go up in flames.

But going back to Armand, even though he is in love with his wife, his treatment of Amalia in L'assamblée is leagues better than it was in season 3. Unlike most of his appearances and his interactions with his sister, where he kept treating her like a child who didn't know any better (what she just so happened to accuse him of when presented with Ashtur, as a matter of fact), here not only does he finally open up to his sister about his insecurities and his reasoning for his behaviour towards her, but he offers her support in the wake of their father's passing and even invites her to attend the assembly with him.

He is entrusting her with responsibilities befitting a queen, not a child.

Their relationship is finally healing.

As I said earlier, despite the undeniable depth behind his character, it's difficult to really side with Armand in plenty of occasions. Not only because of his difficult personality and flaws, but because it is so much easier to sympathise with Amalia.

And I'm not talking exclusively about the fact that, as one of the main characters, we've been by her side throughout everything, witnessing her true selfless, responsible, and brave self, but the fact that her position within her own family certainly tugs at our heartstrings.

Amalia is the youngest sibling, the princess. For all the sheltering and privileges that can get her, it also became her gilded cage. And for the most part, not even her family was a safe haven.

Queen Sheran Sharm died when Amalia was probably still a kid, whereas Armand was most likely already a teenager. As King Oakheart revealed back when he explained to Amalia it had been Armand who insisted they let her go, the queen's death shook their entire family, making the king and prince unintentionally turn their backs on Amalia during a time she needed as much affection as possible. And so, her royal duties became stifling, her royal upbringing unbearable. Thus is the reason for her wanderlust.

And then we have Armand's reason for not always being fair to her: jealousy. He resented her for being Oakheart's favourite, despite constantly going off to adventures while he remained in the kingdom by his side. Now, as I said, this was a great character moment for Armand, one that also belies his character development. However, it doesn't change the fact that, while easier to relate and sympathise with him, we still sympathise with Amalia more or have been doing so for far longer because we knew the effect this had had on her.

We all have been someone's scapegoat to their frustrations with a third person, we have all been treated unfairly by someone who, for whatever reason, couldn't solve their own issues with the person they had problems with in the first place and took it out on us. This is the crux of Armand and Amalia's strained relationship: for years, Armand took his frustrations and insecurities out on Amalia instead of having an honest conversation with their father.

That's why it's easier to sympathise with Amalia, because we know that, deep down, for all her flaws, she was never at fault for how their relationship turned out. Because we can understand her frustration and pain when, even with their dying father, Armand still chose to listen to his wife over her and try to marry her off instead of being there for each other when they both needed most. As Amalia called him out for before leaving with Yugo, he still chose politics over family. Everything involving Armand and Aurora is about politics.

But now that they are at least beginning to rebuild their relationship, I sincerely hope things get better for them. Unless their original intentions back in 2017 have changed, I seriously fear Ankama will still use Aurora to complicate things further between these two.

Please, Ankama, I'm literally begging you. They're all the family they each have left, don't let their relationship be ruined forever.

#wakfu#wakfu spoilers#wakfu season 4#wakfu season 4 spoilers#un nouveau monde#a new world#l'assamblée#the assembly#wakfu analysis#wakfu season 3#falling down#amalia sheran sharm#armand sheran sharm#king oakheart sheran sharm#aurora#wakfu aurora#ankama#osamodas#sadida

183 notes

·

View notes

Text

Below the cut I have made a list of each English and British monarch, the age of their mothers at their births, and which number pregnancy they were the result of. Particularly before the early modern era, the perception of Queens and childbearing is quite skewed, which prompted me to make this list. I started with William I as the Anglo-Saxon kings didn’t have enough information for this list.

House of Normandy

William I (b. c.1028)

Son of Herleva (b. c.1003)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 25 at birth.

William II (b. c.1057/60)

Son of Matilda of Flanders (b. c.1031)

Third pregnancy at minimum, although exact birth order is unclear.

Approx age 26/29 at birth.

Henry I (b. c.1068)

Son of Matilda of Flanders (b. c.1031)

Fourth pregnancy at minimum, more likely eighth or ninth, although exact birth order is unclear.

Approx age 37 at birth.

Matilda (b. 7 Feb 1102)

Daughter of Matilda of Scotland (b. c.1080)

First pregnancy, possibly second.

Approx age 22 at birth.

Stephen (b. c.1092/6)

Son of Adela of Normandy (b. c.1067)

Fifth pregnancy, although exact birth order is uncertain.

Approx age 25/29 at birth.

Henry II (b. 5 Mar 1133)

Son of Empress Matilda (b. 7 Feb 1102)

First pregnancy.

Age 31 at birth.

Richard I (b. 8 Sep 1157)

Son of Eleanor of Aquitaine (b. c.1122)

Sixth pregnancy.

Approx age 35 at birth.

John (b. 24 Dec 1166)

Son of Eleanor of Aquitaine (b. c.1122)

Tenth pregnancy.

Approx age 44 at birth.

House of Plantagenet

Henry III (b. 1 Oct 1207)

Son of Isabella of Angoulême (b. c.1186/88)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 19/21 at birth.

Edward I (b. 17 Jun 1239)

Son of Eleanor of Provence (b. c.1223)

First pregnancy.

Age approx 16 at birth.

Edward II (b. 25 Apr 1284)

Son of Eleanor of Castile (b. c.1241)

Sixteenth pregnancy.

Approx age 43 at birth.

Edward III (b. 13 Nov 1312)

Son of Isabella of France (b. c.1295)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 17 at birth.

Richard II (b. 6 Jan 1367)

Son of Joan of Kent (b. 29 Sep 1326/7)

Seventh pregnancy.

Approx age 39/40 at birth.

House of Lancaster

Henry IV (b. c.Apr 1367)

Son of Blanche of Lancaster (b. 25 Mar 1342)

Sixth pregnancy.

Approx age 25 at birth.

Henry V (b. 16 Sep 1386)

Son of Mary de Bohun (b. c.1369/70)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 16/17 at birth.

Henry VI (b. 6 Dec 1421)

Son of Catherine of Valois (b. 27 Oct 1401)

First pregnancy.

Age 20 at birth.

House of York

Edward IV (b. 28 Apr 1442)

Son of Cecily Neville (b. 3 May 1415)

Third pregnancy.

Age 26 at birth.

Edward V (b. 2 Nov 1470)

Son of Elizabeth Woodville (b. c.1437)

Sixth pregnancy.

Approx age 33 at birth.

Richard III (b. 2 Oct 1452)

Son of Cecily Neville (b. 3 May 1415)

Eleventh pregnancy.

Age 37 at birth.

House of Tudor

Henry VII (b. 28 Jan 1457)

Son of Margaret Beaufort (b. 31 May 1443)

First pregnancy.

Age 13 at birth.

Henry VIII (b. 28 Jun 1491)

Son of Elizabeth of York (b. 11 Feb 1466)

Third pregnancy.

Age 25 at birth.

Edward VI (b. 12 Oct 1537)

Son of Jane Seymour (b. c.1509)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 28 at birth.

Jane (b. c.1537)

Daughter of Frances Brandon (b. 16 Jul 1517)

Third pregnancy.

Approx age 20 at birth.

Mary I (b. 18 Feb 1516)

Daughter of Catherine of Aragon (b. 16 Dec 1485)

Fifth pregnancy.

Age 30 at birth.

Elizabeth I (b. 7 Sep 1533)

Daughter of Anne Boleyn (b. c.1501/7)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 26/32 at birth.

House of Stuart

James I (b. 19 Jun 1566)

Son of Mary I of Scotland (b. 8 Dec 1542)

First pregnancy.

Age 23 at birth.

Charles I (b. 19 Nov 1600)

Son of Anne of Denmark (b. 12 Dec 1574)

Fifth pregnancy.

Age 25 at birth.

Charles II (b. 29 May 1630)

Son of Henrietta Maria of France (b. 25 Nov 1609)

Second pregnancy.

Age 20 at birth.

James II (14 Oct 1633)

Son of Henrietta Maria of France (b. 25 Nov 1609)

Fourth pregnancy.

Age 23 at birth.

William III (b. 4 Nov 1650)

Son of Mary, Princess Royal (b. 4 Nov 1631)

Second pregnancy.

Age 19 at birth.

Mary II (b. 30 Apr 1662)

Daughter of Anne Hyde (b. 12 Mar 1637)

Second pregnancy.

Age 25 at birth.

Anne (b. 6 Feb 1665)

Daughter of Anne Hyde (b. 12 Mar 1637)

Fourth pregnancy.

Age 27 at birth.

House of Hanover

George I (b. 28 May 1660)

Son of Sophia of the Palatinate (b. 14 Oct 1630)

First pregnancy.

Age 30 at birth.

George II (b. 9 Nov 1683)

Son of Sophia Dorothea of Celle (b. 15 Sep 1666)

First pregnancy.

Age 17 at birth.

George III (b. 4 Jun 1738)

Son of Augusta of Saxe-Gotha (b. 30 Nov 1719)

Second pregnancy.

Age 18 at birth.

George IV (b. 12 Aug 1762)

Son of Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (b. 19 May 1744)

First pregnancy.

Age 18 at birth.

William IV (b. 21 Aug 1765)

Son of Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (b. 19 May 1744)

Third pregnancy.

Age 21 at birth.

Victoria (b. 24 May 1819)

Daughter of Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saafield (b. 17 Aug 1786)

Third pregnancy.

Age 32 at birth.

Edward VII (b. 9 Nov 1841)

Daughter of Victoria of the United Kingdom (b. 24 May 1819)

Second pregnancy.

Age 22 at birth.

House of Windsor

George V (b. 3 Jun 1865)

Son of Alexandra of Denmark (b. 1 Dec 1844)

Second pregnancy.

Age 20 at birth.

Edward VIII (b. 23 Jun 1894)

Son of Mary of Teck (b. 26 May 1867)

First pregnancy.

Age 27 at birth.

George VI (b. 14 Dec 1895)

Son of Mary of Teck (b. 26 May 1867)

Second pregnancy.

Age 28 at birth.

Elizabeth II (b. 21 Apr 1926)

Daughter of Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon (b. 4 Aug 1900)

First pregnancy.

Age 25 at birth.

Charles III (b. 14 Nov 1948)

Son of Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom (b. 21 Apr 1926)

First pregnancy.

Age 22 at birth.

365 notes

·

View notes

Text

RTVE is making a new show about Queen Victoria Eugenie of Spain called 'Ena' and I'm pretty impressed with the jewelry so far. This is meant to be Ena on her wedding day in 1906 presumably before the bomb went off. The show is being made by Javier Olivares who also made 'Isabel' about Queen Isabella I of Castile and is currently filming so it won't be out for a while. The jewelry used in shows and movies is never going to look exactly like the real thing unless they spend a ton of their budget on it which isn't going to happen but I appreciate it when they at least try to replicate jewels correctly.

Queen Ena's Fleur de Lys Tiara or as it's commonly called La Buena was made by Ansorena in 1906 as a wedding gift from her husband, King Alfonso XIII of Spain. It has become the most important tiara in the Spanish collection and is now worn by Queen Letizia.

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

Isabel and Juana of Castile + quote

Happy birthday @latristereina !

Isabel had good cause for being upset. Such was “the disposition of the Princess” as the physicians described it, “that not only should it pain those who see her often and love her greatly, but also anyone at all, even strangers, because she sleeps badly, eats little and at times nothing, and she is very sad and thin. Sometimes she does not wish to talk and appears as though in a trance; her infirmity progresses greatly.” It was customary, they explained, to treat Juana’s infirmity through love, entreaty, or fear; but the princess had proven unreceptive to entreaty, and even “a little force” affected her so adversely that it was a great pity to attempt it and no one wanted to try, so that, beyond the queen’s customary immense labors and concerns, this weight of caring for her daughter fell upon her. It has been conjectured that Isabel’s illness could have been cancer, endocarditis—infection of the heart valve—chronic dropsy, or several of them combined. By the following June she had a visible tumor, although it is not known where or of what sort. In August she took Juana to Segovia, which she had seemingly avoided for years, telling her it was a step toward the north coast and her departure for Flanders. There Isabel continued to try with little success to get her to turn her mind to affairs of state.

Juana showed little interest in government and in her child, and a good deal of disregard for religious matters of any sort, and for public opinion as well. The princess appeared to disdain much of what Isabel valued, and even to represent the antithesis of the very qualities her mother valued most highly. Even so, Juana was her designated successor, and Isabel was determined to keep her in Spain and do her best to train her to be its queen. So the arguments against Juana’s departure were patiently repeated: the season, the sea, the French, that Philip should be safe in Ghent before she traveled, and did she not want to see her father before she left? The hope remained that Juana would stay and Charles join her, so that Isabel might have him educated in Spain’s customs and come to prefer its people. And with Juana and Charles there and Philip not, should Isabel die, Fernando, still king of Aragón, could surely manage to guide their daughter in governing Castile.

It was November. A treaty with France—arranged by the queen of France, Anne of Brittany, and Margaret of Austria—had been signed, and an envoy arrived from Philip requesting that Juana return to Flanders. Isabel, playing for time, responded that the princess, although better, was not well, that relations with France were still such that it was not safe for her to travel by land or, now that it was winter, by sea, that she had better wait until spring, and that “following her frame of mind and la pasión she has” that Juana should not be where there was no one who could quiet and restrain her for it might be dangerous for her. The implication was that Juana was emotionally out of control. Exactly what was meant by “restrain” we do not know.

-Peggy K. Liss, Isabel the Queen

#isabel de castilla#isabella of castile#juana de castilla#joanna of castile#joanna i#Isabel tve#juana la loca#mad love#michelle jenner#pilar lopez de ayala#period drama#perioddramaedit#historical women#my edits#graphic edit#filter by crownedfilters on ig

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

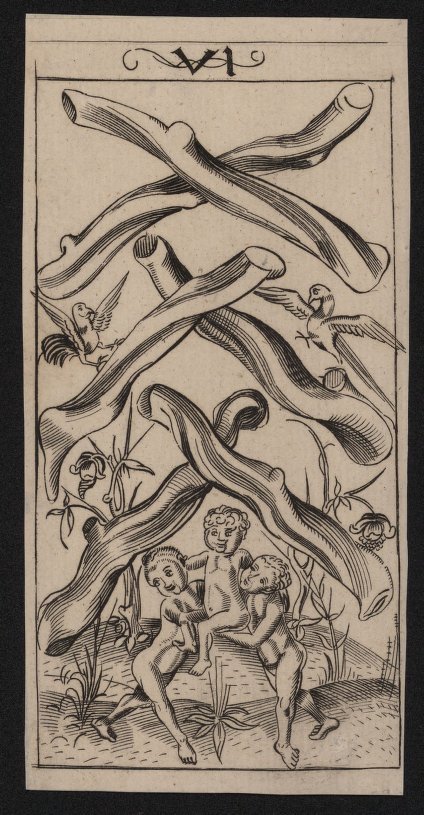

This deck of playing cards is from a series engraved in southern Germany ca. 1496, and is believed to commemorate the marriage in that year of the future King Philip I of Spain (son of the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I) to Joanna the Mad (daughter of King Ferdinand of Aragon and Queen Isabella of Castile). Instead of hearts, spades, clubs, and diamonds, these cards use chalices, swords, pomegranates, and polo sticks.

The University Libraries and a private collector are partnering to make an extensive collection of medieval and early modern materials available to scholarship through digitization. These materials do not belong to the Libraries, but the scans are freely available for use in research and teaching. See more in the University of Missouri Digital Library.

#playing cards#engraving#1400s#1500s#art history#renaissance#printmaking#special collections#specialcollections#university of missouri#mizzou#private collection#columbia mo

303 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marguerite of Provence, Queen of France

Marguerite of Provence, Queen of France

Marguerite of Provence from a fifteenth century manuscript

Raymond-Berengar V, Count of Provence, married Beatrice of Savoy in 1219. Their eldest daughter Marguerite was born in the spring of 1221 in Forcalquier, and they would have three more daughters, all of whom would become queens. Marguerite married Louis IX of France, Eleanor married Henry III of England, Sanchia became queen of the…

View On WordPress

#Beatrice of Provence#Beatrice of Savoy#Blanche of Castile#Charles of Anjou#Count of Provence#Count of Toulouse#Eleanor of Provence#French history#King of France#King of Sicily#Louis IX#Marguerite of Provence#medieval history#Philip III#Philip IV#Queen of England#Queen of France#Raymond VII#Raymond-Berengar V#Sanchia of Provence

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mary de Bohun, Countess of Derby

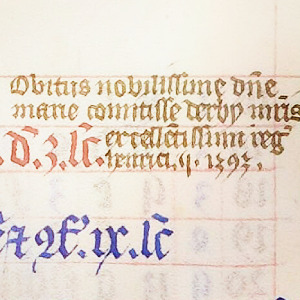

Mary de Bohun was probably born around 22 December 1370 to Humphrey de Bohun and Joan Fitzalan, Earl and Countess of Hereford. As her father had no son, she and her elder sister, Eleanor, became the heiresses of his wealthy earldom. Eleanor married Thomas of Woodstock, the youngest son of Edward III, and according to Froissart, Woodstock intended Mary to enter a nunnery so he would inherit the entire earldom. This was not to be. In late 1380 or early 1381, Mary married John of Gaunt's son and heir, Henry Bolingbroke, the future Henry IV. The marriage appears to have happy as they shared similar interests and often spent time together. The story that Mary gave birth to a short-lived son in 1382, when she would have been only 11, is now believed to be a myth brought into being by a mistranslated text referring to her sister giving birth to a son. Mary's first child was the future Henry V, born 16 September 1386. Four more children soon followed: Thomas, Duke of Clarence (29 September 1387), John, Duke of Bedford (20 June 1389), Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester (3 October 1390) and Blanche, Electress Palatine (25 February 1392). Mary died either giving birth to her sixth and final child, Philippa, Queen of Norway, Denmark and Sweden, or from complications afterwards, on 1 July 1394, when she was only 23 years old. Mary was buried on 6 July 1394 in the Church of the Annunciation of Our Lady of the Newarke in Leicester. The church and her tomb was destroyed in the Reformation.

A little of her personality can be reconstructed. She was interested in music, playing the harp or cithara, and she bought a ruler to line parchment for musical notation, suggesting she may have also composed music.Such an interest was shared by both her husband and eldest son, one or both of whom were the 'Roy Henry' who composed two mass movements. She maintained a close contacts with other noblewomen, not only her mother and sister, but Constanza of Castile, Katherine Swynford and Margaret Bagot, suggesting that she may well have been more politically aware and involved than what is generally believed. She may have also continued the de Bohun of patronising manuscript illuminators. A number of illuminated manuscripts believed to belong to her or her sister are some of the most celebrated late medieval English manuscripts.

Mary never became Duchess of Lancaster, let alone Queen of England, but it was her family's badge of the swan that became associated with the Lancastrian kings, most famously borne by her eldest son, Henry V. One of Henry V's first acts as king was to order a copper effigy for her tomb, while in the charter of his Syon foundation, he required that the soul of "Mary … our most dear mother", among others, be prayed for in a daily divine service. Her third son, John, recorded her anniversary into his personal breviary, while her daughters may have each carried manuscripts belonging to her with them when they left England to be married. Despite the brevity of her life, Mary was remembered long after her death.

Sources: Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, MS Lat. 17294, Chris Given-Wilson, Henry IV (Yale University Press 2017), Ian Mortimer, The Fears of Henry IV (Vintage 2008), John Matusiak, Henry V (Routledge 2012), Calendar of the Patent Rolls: Henry IV. Vol. I. A. D. 1399-1401, Calendar of Close Rolls 1381-1385, Rebecca Holdorph, 'My Well-Beloved Companion': Men, Women, Marriage and Power in the Earldom and Duchy of Lancaster, 1265-1399, University of Southampton, PhD Thesis, Marina Vidas, The Cophenhagen Bohun Hours: Women, Representation and Reception in Fourteenth Century England (Museum Tusculanum Press 2019)

79 notes

·

View notes