#queen of navarre

Text

Marguerite d'Angoulême

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been thinking about the tragedy of Elizabeth Woodville living to see the death of her family name.

I don't mean her family with her husband, which lived on through her daughter and grandson. I mean her own.

Her sisters died, one by one, many of them after 1485. When Elizabeth died, only Katherine was left, and she would die before the turn of the century as well.

All her brothers died, too. Lewis died in childhood. John was executed. Anthony was murdered. Lionel died suddenly in the peak of Richard's reign, unable to see his niece become queen. Edward perished at war. Richard died in grieving peace. For all the violence and judgement the family endured, it was "an accident of biology" that ended their line: none of the brothers left heirs, and the Woodville name was extinguished. We know the family was aware of this. We know they mourned it, too:

“Buy a bell to be a tenor at Grafton to the bells now there, for a remembrance of the last of my blood.”

Elizabeth lived through the deposition and death of her young sons, and lived to see the end of her own family name. It must have been such a haunting loss, on both sides.

#(the quote is by Richard Woodville in his deathbed will; he was the last of the Woodville brothers to die)#elizabeth woodville#woodvilles#my post#to be clear I am not arguing that the death of an English gentry family name is some kind of giant tragedy (it absolutely the fuck is not)#I'm trying to put it into perspective with regards to what Elizabeth may have felt because we know her family DID feel this way#writing this kinda reminded me of how I am just not fond at all about the way Elizabeth's experiences in 1483-85 are written about#and the way lots so many of the unprecedentedly horrifying aspects are overlooked or treated so casually:#the seizure and murder of two MINOR sons and the illegal execution of another;#her sheer vulnerability in every way compared to all her queenly predecessors; how she was harassed by 'dire threats' for months;#how she had 5 very young daughters with her to look after at the time (Bridget and Katherine were literally 3 and 4 years old);#how unprecedented Richard's treatment of her was: EW was the first queen of england to be officially declared an adulteress;#and the first and ONLY queen to be officially accused of witchcraft#(Joan of Navarre was accused of her treason; she was never explicitly accused of witchcraft on an official level like EW was)#the first crowned queen of england to have her marriage annulled; and the first queen to have her children officially bastardized#what former queens endured through rumors* were turned into horrifying realities for her.#(I'm not trying to downplay the nightmare of that but this was fundamentally on a different level altogether)#nor did Elizabeth get a trial or appeal to the church. like I cannot emphasize this enough: this was not normal for queens#and not normal for depositions. ultimately what Richard did *was* unprecedented#and of course let's not forget that Elizabeth had literally just been unexpectedly widowed like 20 days before everything happened#I really don't feel like any of this is emphasized as much as it should be?#apart from the horrifying death of her sons - but most modern books never call it murder they just write that they 'disappeared'#and emphasize that ACTUALLY we don't know what happened to them (this includes Arlene Okerlund)#rather than allowing her to have that grief (at the very least)#more time is spent dealing with accusations that she was a heartless bitch or inconsistent intriguer for making a deal with Richard instead#it also feels like a waste because there's a lot that can be analyzed about queenship and R3's usurpation if this is ever explored properly#anyway - it's kinda sad that even after Henry won and her daughter became queen EW didn't really get a break#her family kept dying one by one and the Woodville name was extinguished. and she lived to see it#it's kinda heartbreaking - it was such a dramatic rise and such a slow haunting fall#makes for a great story tho

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

#please enjoy#his cute little lover faces though#if you play it backwards he gets dressed#check out his cute little monk shirt 🤤#love me a warrior monk#monks with abs#knightfall#knightfall s1 episode 1#perioddramaedit#queen joan#queen joan of navarre#tom cullen#period drama

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

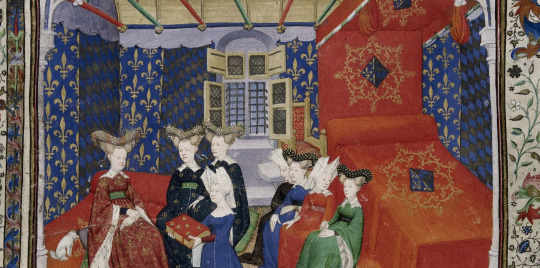

Educating the princesses

“All of these princesses, both foreign and French, had received a first-rate education. Some were raised at the French court from childhood, such as Philip IV’s wife Joan of Navarre and Charles VIII’s young fiancée Margaret of Austria. Others were educated within their own families in their respective principalities.

Educators had long debated what women should be taught. In 1265,

Philip of Novara had advised against teaching girls—except for nuns— how to read and write. He was, however, in the minority. Far from being neglected when it came to aristocratic education, women were the recipients of veritable miroirs aux princesses (didactic works presenting the exemplary image of the good ruler or, for women, the ideal princess), which reveal all the care that went into their training—as religious as it was moral and intellectual.

(...)

Beyond these theoretical treatises, sources on the practice of that time provide information about the educational methods of the period. Young princesses learned to read and often write. Such instruction often took place within the palace under a tutor. At the court of Savoy in the mid-fifteenth century, Pierre Aronchel was the schoolmaster of Louis and Anne of Cypress’s eldest daughters Margaret and Charlotte (future wife of Louis XI).

Like their brothers, young princesses first learned reading and religion. They learned to read using an alphabet book (Margaret of Austria learned the alphabet using a book handsomely bound in black velvet) and continued with psalters and books of hours. At the age of seven, young Joan of France, who was married to the Count of Montfort, received a richly illuminated book of hours of Notre-Dame from her mother Isabeau of Bavaria. During the fourteenth century, young girls at the court of Savoy practiced reading using liturgical collections, matins and penitential psalms, which were replaced by books of hours in the fifteenth century. Like their brothers, Savoyard princesses also learned to write.

Latin, however, was reserved for boys, which was one of the primary differences when it came to education. Princesses only knew the necessary prayers and formulas for following mass and reading their books of hours. There were a few exceptions nonetheless. Saint Louis’s sister Isabella of France (d. 1270), for example, was reputedly an excellent Latinist.

Failing Latin, aristocratic ladies knew other languages. John II’s future wife Bonne of Luxembourg, who had been raised in Bohemia, spoke Czech, German and French. Yolanda of Bar —daughter of Robert, Duke of Bar, and wife of John I, King of Aragon—could read ‘Limousin’ and Latin in addition to being able to write in French and Catalan. Others had a harder time learning a foreign language. During her entry ceremony in Paris in 1389, Isabeau of Bavaria was criticized for her poor understanding of French—four years after she had arrived in the kingdom.”

Queenship in medieval france 1300-1500, Murielle Gaude-Ferragu

#history#women in history#women's history#queens#middle ages#medieval women#france#french history#medieval history#isabeau of bavaria#Joan of navarre

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

CONSORTS OF ENGLAND SINCE THE NORMAN INVASION (2/5) ♚

Eleanor of Castile (November 1272 - November 1290)

Margaret of France (September 1299 - July 1307)

Isabella of France (May 1308 - January 1327)

Philippa of Hainault (January 1328 - August 1369)

Anne of Bohemia (January 1382 - June 1394)

Isabella of Valois (October 1396 - September 1399)

Joan of Navarre (February 1403 - March 1413)

Catherine of Valois (June 1420 - August 1422)

Margaret of Anjou (May 1445 - May 1471)

Elizabeth Woodville (May 1464 - April 1483)

#my photoset.#history#historyedit#history edit#plantagenets#lancaster#house of lancaster#house of york#elizabeth woodville#margaret of anjou#catherine of valois#the king netflix#the white queen#joan of navarre#isabella of valois#anne of bohemia#philippa of hainault#isabella of france#margaret of france#eleanor of castile#royalty#royals#medieval history#medieval queens#queen consorts#war of roses#english history#historical royals#consorts of england#consorts of england and britiain.

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

#house of lancaster#house of Navarre#house of Brittany#Joan of Navarre#Queen Joan#Joanna of Navarre#Queen Joanna#Jehanne d’Évreux#Plantagenet dynasty#Valois dynasty#house of valois#maison des valois#Henry IV#John V#Lancastrian edit#Lancastrian consort#queen of England#medieval England#naomi watts#Jodi comer

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Queen’s Choice by Anne O’Brien

The Queen’s Choice is a pretty average novel, with some good tidbits and some things that got under my skin. But it’s main problems aren’t bad history (though there is some of that), but bad writing. It has the same problem that a lot of historical fiction in the vein of Philippa Gregory has, where the heroine of the novel is not necessarily present at a lot of historically significant moments. The way to counteract this problem is by making her the focus of her own plot, so we aren’t left with nothing but a conspicuous absence. The Queen’s Choice goes in the opposite direction-- almost every important plot element happens off screen. Even the choice the novel is named for happens only in exposition. Joanna’s imprisonment happens after a six year time skip, so it truly comes out of nowhere. The battle of Shrewsbury, the execution of Archbishop Scrope, most of Henry and Joanna’s marriage takes place in letters or single sentences that get cast aside. It conveys, perhaps more than Anne O’Brien intended, that Joanna was a Queen with nothing to do and no importance. Which makes it increasingly laughable every time Joanna is praised for her political knowledge and ability to give good counsel, when we never see her express either attribute and she gets shot down whenever she tries. This Joanna is ironically far less active than any of the information about her indicates, and her characterisation is too flat to give her any other impact.

To put it frankly, it reads like fanfiction-- not just because it’s an easy read, but because it feels like a companion piece, the kind of fic you write about a side character you like but who isn’t very involved in the main plot. If you don’t already know this time period in depth, you won’t have any idea what is going on.

Little Details I liked

Humphrey cheerfully recounting all the ways his father has nearly been murdered.

The concern about Joanna’s entourage and ties to Brittany is shown well. None of it relates at all to her imprisonment, so the foreshadowing and payoff are completely divorced from one another, but it’s nice to see an attempt.

Similarly, Joanna is shown to indulge in plenty of herbs, as does a lot of other characters. I just like when it’s shown a lot of people use potions and tinctures and the like, and how the line between that and witchcraft is essentially whether a person likes you or not.

We get to see a glimpse of Henry’s rising paranoia after taking the crown. It goes nowhere, and the most pressing examples of it are left aside, but again, an attempt was made. Sort of.

Stuff that Irked Me

Blanche is referred to as dying in childbirth. Again.

Henry is barely given a character. Their romance is never given enough detail to be convincing. Frankly, I wonder if the author was more interested in the storyline with Thomas than the one with Henry.

Humphrey stands around listening to people call Hal selfish, greedy, and all sorts after Joanna’s imprisonment, and does nothing. Humphrey.

Henry Beaufort’s characterisation is neither consistent nor sensical.

Henry IV supports the Burgundians in this book, but is reluctant to go to war. Still, he is determined to lead the invasion himself. This plot line is never resolved in a way that makes it historically accurate, it’s just dropped.

Hal is seen on screen perhaps five times. The first is after the Battle of Shrewsbury, where Joanna offers him potions for his scar. The second is him being mentioned to be talking about violently quashing the Welsh. The third, him demanding Henry abdicate (and demand is the right word. Little argument is made, and none that would suggest Hal is concerned at all about Henry’s ill health, just that he wants the power for himself). The fourth is at Henry’s deathbed, wherein Joanna says Hal doesn’t like her very much. Based on these few scenes, and the final chapters in the book where every character on screen (except Humphrey, but he doesn’t say otherwise) is quick to call Hal various insults, I think that Hal is meant to simply be taken as evil. Hal is undoubtedly the villain of Joanna’s story, but as soon as we get Henry saying Hal doesn’t understand why you would want an outspoken wife and Joanna claiming Hal would never take the advice of a woman (forgetting, of course, that Joanna was very active in Hal’s court when he first became King, and Joan FitzAlan’s entire existence), there is no longer room for nuance and subtlety. He is sexist, and violent, and greedy, and he is either Evil or at the very least a real prick who not even his uncle and brother can defend. While wholly unintentional, considering Joanna shows sympathy towards Hal about it and it only, I’m still somewhat annoyed that one of the only times we get Hal with his scar, it’s when he is intended to be as unsympathetic as possible.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queen Isabella: The She-Wolf of France

Isabella's coat of arms shows four quarters: the first of her husband, Edward II of England, the second of her father, Philip IV of France, the third and fourth of her mother, Joan I of Navarre, Countess of Champagne.

Image of Isabella, click to enlarge.

Isabella was born the sixth child of King Philip IV of France and Queen Joan I of Navarre. She was the third daughter born, but their only surviving daughter eventually (Margaret had died in childhood in 1300 and Blanche had died after 13th April, 1294). Although Isabella's date of birth is uncertain, both the French chronicler Guillaume de Nangis and the English chronicler Thomas Walshingam describe her as 12 years old at the time of her marriage in January 1308, making it seem that her likely birthdate was between January 1295 and 1296. During her lifetime, she would see three of her brothers, Louis, Philip, and Charles become kings of France.

Isabella was given a good education, taught to read and write, and eventually developed a love of books. She, much like the rest of her siblings, was promised in marriage at a young age. Her father secured a match with Prince Edward, the future King Edward II of England, son of King Edward I of England. The marriage was made with the intentions to resolve the conflicts between England and France over possession and claims of land such as Gascony, Normandy, Anjou and Aquitaine. Pope Boniface VIII had urged for the wedding to go ahead as early as 1298, meaning Isabella would be around only 3 years old while Edward would have been around 14 years old. Edward I of England attempted to break the engagement several times, and it only went ahead when Edward I died in 1307.

Edward, now King Edward II of England, married Isabella of France on the 25th of January, 1308 at Boulogne-sur-Mer in France. Isabella was probably around 12 years old at the time of her marriage. She was now the Queen consort of England. Edward was 23 years old. During the wedding feast, Edward chose to sit with Piers Gaveston, a favourite of his, rather than Isabella. She soon complained to her father that she received insufficent funds and that Edward visited Galveston's bed more than her own. Eventually, Edward was force to exile Gaveston to Ireland for a period of time to show respect to Isabella.

Isabella depicted as queen.

Edward had male favourites at court: Piers Gaveston and Hugh Despenser the Younger. When Edward became king, he had inherited a country at war with Scotland, and with his own barons, in particular his first cousin, Thomas, the 2nd Earl of Lancaster, who was a grandson of Henry III of England, and who's uncle had been Edward I of England. Isabella found her way through these challenges, forming a successful alliance with Gaveston, until his death at the hands of the barons. Isabella found herself at increasing odds with her husband when Edward allied himself with the Despenser family, particular Hugh the Younger.

Between the years of 1312 and 1321, Isabella gave birth to four children and is said to have suffered at least one miscarriage. A son, Edward, the future Edward III, was born in 1312; another son, John, Earl of Cornwall, was born in 1316; a daughter, Eleanor of Woodstock, was born in 1318; and another daughter, Joan of the Tower, was born in 1312. Her daughter Joan went on to marry King David II of Scotland in accordance with the Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton.

There even appears to have been an attempt to capture Isabella at one point in 1319. The Scottish general, Sir James Douglas, who was a war leader for Robert I of Scotland, personally tried to capture Isabella at York and almost succeeded, however Isabella just barely escaped. It was unproven though suspicions fell of Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, and a knight of Edward's, Edmund Darel. It was during this time that Edward had begun a sexual relationship with Hugh the Younger, and had begun making enemies in the form of the Mortimer's. With Lancaster moving against them, Isabella pleaded with Edward on her knees to send the Despensers into exile, which he did and vowed to bring them back at the first opportunity available to him.

By January 1322, Edward's army was reinforced with the Despensers returning from exile. They had forced surrender from the Mortimers and by March 1322, Lancaster had been captured after the Battle of Boroughbridge and executed. Another campaign for Scotland resulted in failure when Isabella was cut off from the South, refused help from the Despenser forces, and her husband had retreated south and had left her and her household. Eventually, Isabella made it to York but she was furious with both Edward and the Despensers.

Isabella had efectively separated from Edward from here onwards and by the end of 1322 had left for a 10 month long pilgramage around England by herself. By 1324, tensions between England and France had grown, and Edward and the Despensers had confiscated all of Isabella's lands, began running Isabella's household, arrested and imprisoned her French staff, and had taken away her children from her, putting them in the custody of the Despensers.

Hugh Despenser the Younger and Edmund Fitzalan brought before Isabella for trial in 1326 before they were executed.

Future Edward III as a boy showing homage to his uncle, Charles IV of France centre right, with his mother, Isabella, in September 1325.

When Charles IV of France, Isabella's brother, seized Edward II's French possesions in 1325, Isabella returned to France. Initially, she was to be a delegate to negotiate a peace treaty between the two nations, however Isabella gathered an army to oppose Edward, in alliance with Roger Mortimer, the 1st Earl of March, with whom she had entered into a relationship. When they returned to England with their army, they quickly took the country, forcing Edward's abdication and executing the Despensers. Edward was held in the custody of Henry of Lancaster, the brother of the late Thomas, Earl of Lancaster.

Isabella had her son, Edward, confirmed as Edward III of England with herself being appointed as regent in January of 1327. On the 23rd of September of the same year, Isabella and Edward III were informed of Edward's death while imprisoned in Berkeley Castle on the Welsh borders. Though described as a "fatal accident", there was a rumour that Isabella and Roger Mortimer had had Edward murdered, and another rumour that said he was alive somewhere in Europe.

During her regency, Isabella had her son, Edward, married to Philippa of Hainault in 1328, something she had agreed to before the invasion of England had taken place. She had her daughter, Joan, married to David, the son of Robert the Bruce, in 1328 also. She also had Edward III renounce any claims on Scottish lands in exchange for the promise of Scottish military aid against any enemy, except the French, and £20,000 in compensation for the raids across northern England. Isabella tried to claim the French throne on behalf of her son, demanding France to recognise her sons claim. When that failed, she decided to court France's neighbours by proposing marriage between her son, John, into the Castilian royal family.

Isabella practically ruled England for her child as regent along with Mortimer for four years, until Edward III deposed Mortimer in a coup and taking the authority for himself in mid-1330. Mortimer was executed at Tyburn on the 29th of November, 1330, aged 43 years.

In Isabella's final years, she became close to her daughter, Joan, doted on her grandchildren, including Edward, the Black Prince, and became interested in religion. She took the nun's habit of the Poor Clares before she died on the 22nd of August in 1358 at Hertford Castle. Her body was returned to London and buried at the Franciscan church at Newgate. At her request, she was buried in the mantle she had worn at her wedding. Her husband's heart was interred with her. She left the bulk of her property to Edward, the Black Prince, reported to be her favourite grandchild, and some person effects to her daughter, Joan.

Over the years, she has been portrayed in both theatre and film, most notably by Tilda Swinton in Edward II (1991) and by French actress Sophie Marceau in Braveheart (1995).

(Information cited from Wikipedia, History of Royal Women, Britannica, World of History, and History Extra)

#isabella of france#she-wolf#france#england#edward ii#edward iii#rogert mortimer#thomas lancaster#hugh despenser the younger#despensers#scotland#philippa of hainault#piers gaveston#philip iv of france#joan i of navarre#edward ii of england#edward iii of england#queen of england#queen consort#history#royal history#history with joanna

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

They’ve cast Minnie Driver as Elizabeth I in The Serpent Queen S2 👀

This will probably be a continuation of the ‘MQOS believing she was plotting with Elizabeth’ storyline from S1

#catherine de medici and elizabeth i in this one drama#please keep Estelle Paranque in your thoughts#the serpent queen#elizabeth i#if we don’t got BE at least we’ve got this i guess?#also Arthur from TSP playing Henry of Navarre

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Review: Queens of the Crusades – by Alison Weir

I had previously read Alison Weir’s most excellent book specifically on Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine many years ago so the author was familiar to me. I chanced upon this title in my local library (Caldicot) and thought I’d give it a go. It covers the lives of several British Queens, or rather the historical period in England during which they lived. The period is one of the most interesting…

View On WordPress

#1215#Alienor of Provence#Alison Weir#Aquitaine#barons#battle#Berengeria of Navarre#British Empire#British Hostory#British Queens#Brittany#Caernarfon#Caernarfon Castle#Caldicot#cardiff#Chepstow#consanguinity#Constantinople#constitution#Continental Europe#Cross#dominions#Edward I#Ekleanor of Castile#Eleanor of Aquitaine#English Queens#europe#European Royal#france#French

7 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Joan was rewarded with grants and privileges from the Crown, mostly under Henry IV and Henry V although she received licences to hunt in the king’s forests and parks in 1392 and 1395 from Richard II. She may well have enjoyed hunting; Henry V in 1414 granted her the right to hunt in Hatfield Forest. More valuable were grants involving property, such as John Holland’s London house and, temporarily, Hadleigh castle in 1400; the right to live in Rochester castle and to be responsible for its custody in the absence of Sir William Darundell, in 1399; and Leeds castle in Kent in 1414. Not all grants were permanent; in 1401 Joan was to hold the patronage of the hospital of St. Katherine by the Tower of London for as long as there was no queen.

Jennifer C. Ward, "Joan de Bohun, Countess of Hereford, Essex and Northampton, c. 1370-1419: family, land and social networks", Essex Archaeology and History, vol. 32, 2001

#joan fitzalan countess of hereford#henry iv#henry v#richard ii#she does seem to have taken on the roles of a quasi queen#in the court of henry iv (at least until he married joan of navarre)#rebecca holdorph notes she was referred to as the king's mother#though holdorph argues that joan took on roles henry's still-living stepmother - katherine swynford - was uninterested in#whereas it's more likely imo that katherine might have been in poor health (she died in 1403 vs joan who died in 1419)#or considered an inappropriiate or awkward figure for that role because of her scandalous past#and of course joan was the biological grandmother of henry's children and heirs when katherine swynford wasn't

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blanche, Marguerite, and Queenship

Blanche's actions as queen dowager amount to no more than those of her grandmother and great-grandmother. A wise and experienced mother of a king was expected to advise him. She would intercede with him, and would thus be a natural focus of diplomatic activity. Popes, great Churchmen and great laymen would expect to influence the king or gain favour with him through her; thus popes like Gregory IX and Innocent IV, and great princes like Raymond VII of Toulouse, addressed themselves to Blanche. She would be expected to mediate at court. She had the royal authority to intervene in crises to maintain the governance of the realm, as Blanche did during Louis's near-fatal illness in 1244-5, and as Eleanor did in England in 1192.

In short, Blanche's activities after Louis's minority were no more and no less "co-rule" than those of other queen dowagers. No king could rule on his own. All kings- even Philip Augustus- relied heavily on those they trusted for advice, and often for executive action. William the Breton described Brother Guérin as "quasi secundus a rege"- "as if second to the king": indeed, Jacques Krynen characterised Philip and his administrators as almost co-governors. The vastness of their realms forced the Angevin kings to rely even more on the governance of others, including their mothers and their wives. Blanche's prominent role depended on the consent of her son. Louis trusted her judgement. He may also have found many of the demands of ruling uncongenial. Blanche certainly had her detractors at court, but she was probably criticsed, not for playing a role in the execution of government, but for influencing her son in one direction by those who hoped to influence him in another.

The death of a king meant that there was often more than one queen. Blanche herself did not have to deal with an active dowager queen: Ingeborg lived on the edges of court and political life; besides, she was not Louis VIII's mother. Eleanor of Aquitaine did not have to deal with a forceful young queen: Berengaria of Navarre, like Ingeborg, was retiring; Isabella of Angoulême was still a child. But the potential problem of two crowned, anointed and politically engaged queens is made manifest in the relationship between Blanche and St Louis's queen, Margaret of Provence.

At her marriage in 1234 Margaret of Provence was too young to play an active role as queen. The household accounts of 1239 still distinguish between the queen, by which they mean Blanche, and the young queen — Margaret. By 1241 Margaret had decided that she should play the role expected of a reigning queen. She was almost certainly engaging in diplomacy over the continental Angevin territories with her sister, Queen Eleanor of England. Churchmen loyal to Blanche, presumably at the older queen’s behest, put a stop to that. It was Blanche rather than Margaret who took the initiative in the crisis of 1245. Although Margaret accompanied the court on the great expedition to Saumur for the knighting of Alphonse in 1241, it was Blanche who headed the queen’s table, as if she, not Margaret, were queen consort. In the Sainte-Chapelle, Blanche of Castile’s queenship is signified by a blatant scattering of the castles of Castile: the pales of Provence are absent.

Margaret was courageous and spirited. When Louis was captured on Crusade, she kept her nerve and steadied that of the demoralised Crusaders, organised the payment of his ransom and the defence of Damietta, in spite of the fact that she had given birth to a son a few days previously. She reacted with quick-witted bravery when fire engulfed her cabin, and she accepted the dangers and discomforts of the Crusade with grace and good humour. But her attempt to work towards peace between her husband and her brother-in-law, Henry III, in 1241 lost her the trust of Louis and his close advisers — Blanche, of course, was the closest of them all - and that trust was never regained. That distrust was apparent in 1261, when Louis reorganised the household. There were draconian checks on Margaret's expenditure and almsgiving. She was not to receive gifts, nor to give orders to royal baillis or prévôts, or to undertake building works without the permission of the king. Her choice of members of her household was also subject to his agreement.

Margaret survived her husband by some thirty years, so that she herself was queen mother, to Philip III, and was still a presence ar court during the reign of her grandson Philip IV. But Louis did not make her regent on his second, and fatal, Crusade in 1270. In the early 12605 Margarer tried to persuade her young son, the future Philip III, to agree to obey her until he was thirty. When Philip told his father, Louis was horrified. In a strange echo of the events of 1241, he forced Philip to resile from his oath to his mother, and forced Margaret to agree never again to attempt such a move. Margaret had overplayed her hand. It meant that she was specifically prevented from acting with those full and legitimate powers of a crowned queen after the death of her husband that Blanche, like Eleanor of Aquitaine, had been able to deploy for the good of the realm.

Why was Margaret treated so differently from Blanche? Were attitudes to the power of women changing? Not yet. In 1294 Philip IV was prepared to name his queen, Joanna of Champagne-Navarre, as sole regent with full regal powers in the event of his son's succession as a minor. She conducted diplomatic negotiations for him. He often associated her with his kingship in his acts. And Philip IV wanted Joanna buried among the kings of France at Saint-Denis - though she herself chose burial with the Paris Franciscans. The effectiveness and evident importance to their husbands of Eleanor of Provence and Eleanor of Castile in England led David Carpenter to characterise late thirteenth-century England as a period of ‘resurgence in queenship’.

The problem for Margaret was personal, rather than institutional. Blanche had had her detractors at court. It is not clear who they were. There were always factions at courts, not least one that centred around Margaret, and anyone who had influence over a king would have detractors. They might have been clerks with misgivings about women in general, and powerful women in particular, and there may have been others who believed that the power of a queen should be curtailed, No one did curtail Blanche's — far from it. By the late chirteenth century the Capetian family were commissioning and promoting accounts of Louis IX that praise not just her firm and just rule as regent, but also her role as adviser and counsellor — her continuing influence — during his personal rule. As William of Saint-Pathus put it, because she was such a ‘sage et preude femme’, Louis always wanted ‘sa presence et son conseil’. But where Blanche was seen as the wisest and best provider of good advice that a king could have, a queen whose advice would always be for the good of the king and his realm, Margaret was seen by Louis as a queen at the centre of intrigue, whose advice would not be disinterested.

Surprisingly, such formidable policical players at the English court as Simon de Montfort and her nephew, the future Edward I, felt that it was worthwhile to do diplomatic business through Margaret. Initially, Henry III and Simon de Montfort chose Margaret, not Louis, to arbitrate between them. She was a more active diplomat than Joinville and the Lives of Louis suggest, and probably, where her aims coincided with her husband’s, quite effective.

To an extent the difference between Blanche’s and Margaret’s position and influence simply reflected political reality. Blanche was accused of sending rich gifts to her family in Spain, and advancing them within the court. But there was no danger that her cultivation of Castilian family connections could damage the interests of the Capetian realm. Margaret’s Provençal connections could. Her sister Eleanor was married to Henry III of England. Margaret and Eleanor undoubtedly attempted to bring about a rapprochement between the two kings. This was helpful once Louis himself had decided to come to an agreement with Henry in the late 1250s, but was perceived as meddlesome plotting in the 1240s. Moreover, Margaret’s sister Sanchia was married to Henry's younger brother, Richard of Cornwall, who claimed the county of Poitou, and her youngest sister, Beatrice, countess of Provence, was married to Charles of Anjou. Sanchia’s interests were in direct conflict with those of Alphonse of Poitiers; and Margaret herself felt that she had dowry claims in Provence, and alienated Charles by attempting to pursue them. Indeed, her ill-fated attempt to tie her son Philip to her included clauses that he would not ally himself with Charles of Anjou against her.

Lindy Grant- Blanche of Castile, Queen of France

#xiii#lindy grant#blanche of castile queen of france#blanche de castille#grégoire ix#innocent iv#raymond vii de toulouse#aliénor d'aquitaine#louis ix#philippe ii#guérin#louis viii#marguerite de provence#aliénor de provence#alphonse de poitiers#henry iii of england#philippe iii#jeanne i de navarre#philippe iv#simon de montfort#edward i of england#jean de joinville#sancia de provence#béatrice de provence#charles i d'anjou

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In total, Leonor governed Navarre as lieutenant, with some minor hiatuses, from 1455 to 1479, making her the effective ruler of the realm for nearly twenty five years. Out of her female predecessors, only Juana I served a longer period; however, Juana I was detached from the governance of the realm and physically distant from Navarre. Leonor however, remained in the kingdom throughout her lieutenancy, making her the female sovereign with the highest record of residency in Navarre.

One of the enabling factors for Leonor’s constant presence in the realm was the “Divide and Conquer” power-sharing mechanism that she employed with her husband, Gaston of Foix. Blanca and Juan had a similar division of duties, but unlike her parents’ often contrary objectives, all of Leonor and Gaston’s actions can be seen to be working toward their joint goals of obtaining the Navarrese crown and politically dominating the Pyrenean region. In order to achieve their ambitions, the couple were adept at working as a team even when physically seperated or carrying out divergent duties.

Politically, it appears that they took on different areas of negotiatiion. Gaston was the designated emissary to the French court, which was entirely appropriate as one of the French king’s leading magnates. One important example of his involvement in negotiations of this type include Gaston’s visit to the French court in the winter of 1461–62 to negotiate the marriage between their heir and the French princess, Magdalena, which ensured Louis XI’s backing for Leonor’s promotion to primogenita. Gaston also conducted negotiations on behalf of his father-in-law, Juan of Aragon, with the King of France, with a successful outcome in the case of the Treaty of Olite in April 1462, which was intimately connected to the marriage that Gaston was orchestrating for his son and Magdalena of France.

Even though Gaston normally took on the role of intermediary with the French crown, there are two letters issued by Leonor during her marriage in December 1466 as lieutenant of Navarre that show her involvement in French affairs. These letters were written during a period of extreme crisis, when Juan II’s difficulties in Catalonia were matched with Leonor’s continuing struggle with the Peralta clan in Navarre. In these letters, Leonor was playing on her familial connection to Louis XI, in hopes of his aid and backing, asking him to “commend this poor kingdom and the said princess to him [Louis XI] as one who is of his house.” Moreover, these letters show Leonor’s independent interaction in crucial diplomatic negotiations with France, both in receiving embassies directly from Louis and in sending her own personal ambassador, Fernando de Baquedano, with detailed instructions on how to proceed.

Gaston appears to have been more engaged with marital negotiations for their numerous offspring than Leonor. However, this may be due to the fact that the couple overwhelmingly chose French marriages for their children. Only three of Leonor’s children did not contract a French betrothal: Pierre who became a cardinal, a daughter who died young, and Leonor’s youngest son, Jacques (or Jaime), who married into the Navarrese nobility. Given the fact that Gaston was more intimately connected to the French court and the nobility of the Midi, it seems reasonable that he would take on the role of chief negotiator for these matches. All of the marital arrangements for their children were made in order for Gaston and Leonor to achieve their joint goals, the acquisition of the throne of Navarre and the consolidation of their power and influence in the Pyrenean region.

Another area where Gaston necessarily played a more central role was militarily. Robin Harris acknowledges Gaston’s successful military career and notes that after his useful military service to the French crown, “the comte was permitted by the [French] king in the last years of his life to employ his military resources in order to further his family’s interests in Navarre.” Gaston also performed many military services for his father-in-law; the agreement of 1455 that promoted Leonor and Gaston to the successors of the realm required Gaston to go to Navarre on Juan’s behalf and retake those areas that had fallen to the rebels “for the honor of the King of Navarre as well as for his own interests and those of the princess his wife."

However, there is some evidence for Leonor’s involvement in one military foray. In the winter of 1471, Leonor took part in a daring attempt to seize the capital, Pamplona, from her opponents, the Beaumonts. Leonor participated in an attempt to storm one of the city gates with a group of armed supporters. Moret notes that “this surprise was reckless; for it exposed the person of the princess to obvious risk and was somewhat rash.” Moreover, the element of surprise was ruined by the cries of her supporters shouting “ Viva la Princesa !” which alerted the Beaumont troops to the threat, and Leonor and her supporters were swiftly ejected from the city.

Like her mother, the noted peacemaker, Leonor was also involved in moves to reduce the civil discord in the realm. Zurita credited Leonor with “making a great effort to resolve the differences of the parties and subdue the kingdom into union and calm.” Leonor represented her father in negotiations for a truce with the supporters of the Principe de Viana on March 27, 1458, at Sang ü esa. Zurita notes, “The princess Lady Leonor was there at that time in Sangüesa and signed the treaty with the power of the king her father.” Leonor was instrumental in the forging of another truce that was contracted in Sangüesa, in January 1473, and she was also present at a conference with her father and her half-brother Ferdinand in Vitoria in 1476 “accompanied by the nobility of Navarre to renew the treatties . . . and attempt to arrive at a stable peace.

Although both spouses were named to the lieutenancy of Navarre, the documentary evidence clearly demonstrates that Leonor appears to have taken on the bulk of the administration of the realm. This was entirely appropriate as it was Leonor, not Gaston, who had the hereditary right to the crown. Moreover, it was logical for Leonor to remain in Navarre so that her husband could look after his own patrimonial holdings and continue to serve as a military commander for the King of France.

Leonor was an active lieutenant but she struggled to implement her rule fully across the kingdom, as many areas were dominated by the Beaumont faction who were opposed to her and her father Juan of Aragon. This meant that at times, she had no control or access to certain key cities in the realm, including the capital, as mentioned previously. Her grandfather’s impressive seat at Olite was the center of her sister’s court, but Leonor eventually regained her hold on the castle and used it as one of her primary residences between 1467 and 1475. Sangüesa remained an important base for Leonor, and she was also associated with Tudela on the southern edge of the kingdom.

Leonor’s difficulty in implementing her rule across the whole of the kingdom is illustrated by a prolonged struggle between the lieutenant and the town of Tafalla, which consistently refused to send representatives when she called together meetings of the Cortes. Tafalla was a center of Beaumont strength, which had supported her brother Carlos in his struggle with Juan of Aragon and was thus bitterly opposed to her appointment to the lieutenancy. Between 1465 and 1475 there is a series of missives from Leonor both summoning representatives from the town and then expressing disappointment when they failed to arrive. During this period, Leonor appears to have called a meeting of the Cortes at least six times, but the town consistently refused to send envoys to the assembly. There is a sense of increasing exasperation and anger in these documents at the repeated failure to participate in these important events. At one point, in late 1471, Leonor personally came to the town to give advance notice of her intent to call another Cortes the following summer, perhaps to circumvent any excuse that the town did not have sufficient time to send representatives, but Tafalla still did not participate in the assembly.

As her authority was contested, Leonor was keen to stress her agency and her position in the documents that she issued. However, at times she even struggled with the chancery; between 1472–73, Juan de Beaumont retained the seals of the kingdom and refused to let Leonor have access to them. In 1475, she granted a reduction in taxes to the important city of Estella acknowledging the reduced capacity of the city to pay after the population had shrunk from the effects of war and flooding. In this document she stressed her efforts to assist all of the urban centers of the realm, to help them recover from the years of civil conflict and devastation, “the other good towns of the said realm have been refurbished by our certain knowledge, special grace, our own change and royal authority.

Leonor’s address clause drew on all of her family and marital ties as a means of establishing her authority:

“Lady Leonor, by the grace of God princess primogenita , heiress of Navarre, princess of Aragon and Sicily, Countess of Foix and Bigorre, Lady of Bearn, Lieutenant general for the most serene king, my most redoubtable lord and father in this his kingdom of Navarre.”

The signet that Leonor used for the majority of her lieutenancy as well as her sello secreto had heraldic devises that mirror her address clause, bearing the arms Navarre, her family dynasty of Evreux, her husband’s counties of Foix, Béarn, and Bigorre, and finally the Trast á mara connections to Aragon, Castile, and Léon.

To sum up, Gaston and Leonor’s ability to divide up roles and responsibilities demonstrates the couple’s effective partnership, using each partner in the most appropriate arena. Moreover, this division was entirely necessary as the couple’s widespread territorial holdings and the demands of balancing the complicated and difficult political situation both within Navarre and the Midi and between France, Castile, and Aragon meant that both partners needed to be fully engaged and active in order to achieve their mutual goals and further their dynastic interests.

Even though Leonor and Gaston generally employed this mode of “Divide and Conquer” that left Leonor primarily responsible for the administration of Navarre while Gaston oversaw his own sizable patrimony, the couple did work together as a unit whenever possible. Documentary evidence shows that Gaston came to stay with Leonor in Navarre for short periods, particularly during the autumn of 1469 and 1470. There is also some additional evidence to indicate an earlier reunion in 1464, which appears to indicate a desire on the part of the couple to be together. Gaston and his party were stuck in the mountain passes between Foix and Navarre on his way to visit Leonor. The princess issued a series of orders to dispatch men and pay for additional recruits and mules in the mountains in order to clear the passes and roads for Gaston, including one order for 300 men to be sent to help. Gaston’s death in 1472 took place on another journey to see his wife in Navarre; he died en route of natural causes in the Pyrenean town of Roncesvalles.

Overall, Gaston and Leonor worked together with the mutual goal of obtaining the crown of Navarre, throwing the weight of Gaston’s power, wealth, connection, and military forces behind Leonor’s hereditary rights and were willing to fight off opposition from their own family in order to succeed. They worked in partnership, with each partner taking on the most appropriate role; Leonor was responsible for the governance of Navarre, and Gaston supported her militarily and financially. They both worked on diplomatic efforts to achieve their ambitions; Gaston used his position as a powerful French vassal and general to gain support while Leonor negotiated with her Iberian relatives to maintain their rights.

[...] Tragically perhaps, Leonor hardly had a chance to enjoy the position of queen regnant when it finally came her way. Leonor’s death, only a few weeks after her father’s in February 1479, meant that her rule as queen lasted less than a month. Leonor changed her address clause to reflect her altered position as “Queen of Navarre, Princess of Aragon and Sicily, Duchess of Nemours, of Gandia, of Montblanc and Peñafiel, Countess of Bigorre and Ribagorza and Lady of Balaguer.” Ram í rez Vaquero points out that most of these titles were disputed; several were titles that should have come to her as part of her paternal inheritance from her father but in reality would have gone to her half-brother Ferdinand de Aragon. In addition, the French titles that Leonor had held as Gaston’s wife had already been passed to her grandson. It appears that Leonor had enough time to mount a formal coronation, on January 28, 1479, at Tudela, firmly establishing herself as Queen of Navarre, even if only for a brief moment. Moret remarked that “out of all the kings and queens of Navarre she was the one who reigned the shortest, although she may have been the one who desired [the crown] most.”

-Elena Woodacre, "Leonor: Civil War and Sibling Strife", "The Queens Regnant of Navarre: Succession, Politics and Partnership, 1274-1512" (Queenship and Power)

#gotta love ruthless ambitious mutually devoted power couples 💅#(they can have a little fratricide. as a treat)#historicwomendaily#Leonor of Navarre#Gaston of Foix#aka the self-declared malewife#Navarre history#Leonor fighting and scheming and waiting for the throne for decades only to finally succeed and then die less than a month later#biggest of Ls honestly#I do wonder what she would have thought about that twist of fate#Was she bitter about the hollow victory of it all?#Or was there nothing but satisfaction that she died as the Queen of Navarre#a position she had fought for for so long#or...both?#(also let's get one loud 'BOO' for Juan the Faithless aka one of the worst historical fathers I have ever read about)#(this is the guy who raised Ferdinand 'I'm going to lock up my own daughter' of Aragon btw. This is where he learned it from)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Knightfall s1 Episode 9

#knightfall#tom cullen#olivia ross#knightfall Gawain#BETRAYAL#queen joan#queen joan of navarre#Knightfall s1 episode 9

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

CONSORTS OF ENGLAND SINCE THE NORMAN INVASION (1/5) ♚

Matilda of Flanders (December 1066 - November 1083)

Matilda of Scotland (November 1100 - May 1118)

Adeliza of Louvain (January 1121 - December 1135)

Geoffrey V of Angou (April 1141 - 1148)

Matilda of Boulogne (December 1135 - May 1152)

Eleanor of Aquitaine (December 1154 - July 1189)

Margaret of France (1170 - June 1183)

Berengaria of Navarre (May 1191 - April 1199)

Isabella of Angoulême (August 1200 - October 1216)

Eleanor of Provence (January 1236 - November 1272)

#my photoset.#royal edit#history#historyedit#matilda of scotland#matilda of flanders#adeliza of louvain#geoffrey v#eleanor of aquitaine#margaret of france#berengaria of navarre#isabella of angouleme#eleanor of provence#british royal family#british royals#royals#royal#queens#historical royals#medieval ages#british royalty#historical royalty#consorts of england since norman invasion#english history#plantagenets#house of normandy#house of blois#plantagenet dynasty#consorts of england since norman invasion edit#consorts of england and britiain.

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

On this day in History, 10 June 1432, Jeanne d'Évreux, daughter of Navarre, died at Havering-atte-Bower. She was formerly Duchess of Brittany by her first marriage, and Queen of Enfland by her second marriage, which was a love union. Despite being imprisoned for some years by her stepson, Henry V, Joan (as she was better known by her English subjects) still received visits from her stepchildren such as Humphrey of Gloucester and John of Bedford, but more often her Beaufort in-laws like Cardinal Beaufort. She was buried next to Henry.

#house of lancaster#house of evreux#jeanne d'evreux#joan of navarre#henry iv of england#queen joan#dowager queen of england#dowager duchess of brittany#plantagenet dynasty

12 notes

·

View notes