#sir brian de bois guilbert

Text

#ivanhoe#sir brian de bois guilbert#combat#duel#brian de bois guilbert#ashby#tournament#art#history#england#europe#knights#medieval#middle ages#rowland wheelwright#knight#armour#plume#plumes#wilfred of ivanhoe

285 notes

·

View notes

Text

James Mason REview:Ivanhoe

So I was in the mood to watch the work of actor James Mason and decided to check out one of his later works Ivanhoe

In this 1982 TV movie King Richard (Julian Glover ) has returned from the CRusades and has teamed up with Robin Hood (DAvid Robb ) to take on three knights who work for Prince John(Ronald Pickup):Sir Reginald Front-de-Boeuf (John Rhyse Davies) who wants to extort Isaac of York (James Mason ),Sir Maurice de Bracy(STuart Wilson ) who wishes to marry Lady Rowena (Lysette Anthony ) and Sir Brian de Bois-Guilbert (Sam Niel ) who is in mad lust for ISaacs daughter REbecca(Olivia Hussey )....Oh and there is a guy named Ivanhowe(Anthony Andrews),hes there too

SO I very much enjoy this movie despite it having a big flaw ....IN THAT IVANHOWE IS THE LEAST INTERESTIN?G PART .Oh Anthony Andrews plays him well,and he connects all these threads...He just isnt given enough focus .He is out of commission for most of the movie and honestly....I dont care about his story ,which is about him reconnecting with his father (Played by Michael Hordern )...PArtially cause the father is such a dick I dont care about him either ,cause the movie doesnt care either.The film is far more focused on the stuff around Ivanhowe that he feels like an after thought

That said I do like the movie.....Because the rest of it is so damn good .The action is solid from the jousting scenes to an assault on the villains castle by Richard and Robin Hood to a very eintense sword fight between Ivanhoe and Sir Brian de Bois-Guilbert.I also like that the film really focuses on prejudice ,both the feud of the Normans and Saxxons but especially the hatred Isaac and REbecca face for being Jewish

The cast is alll superb (I mean Sam Niel,Stuart Wilson and John Rhyse Davies are the villains how can I not love that),Both George Innes and Tony Haygarth bring levity as Wamba the Fool and Friar Tuck rspectfully ,Michael Hordern is appropriatly pigheaded as Cedric , Wilson and Davies are sinister ,Phillip Locke is scene stealingly evil as the leader of the Knights Templar ,ROnald Pickup is slimey and David Robb is a solid Robin Hood (He also gets the funniest line )

The best performances however go to Julian Glover,James Mason ,Olivia Hussey ,and Sam Niel .Lets Start with Niel who is a solid villain :Arrogant ,obsessive ,creepy and yet there are levels to it ,fighting genuine guilt for his actions .Julian Glover is an actor I associate with bad guys so its fun to see him as a noble king .Olivia Hussey is great as REbecca,on par with Elizabeth Taylors performance in the 1952 film.I think the scene stealer of the movie is James Mason ,Mason while associated with lets say darker parts,had great versitility and when he had the chance could make a very sympathetic characters cause he can make the audience feel his pain

Ovewralll its a fun movie,and I think its on par with the 1952 film

@filmcityworld1 @angelixgutz @ariel-seagull-wings@amalthea9 @the-blue-fairie @themousefromfantasyland @theancientvaleofsoulmaking @scarletblumburtonofeastlondon @princesssarisa

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brian de Bois-Guilbert doesn't even just fail at courtly love, he entirely inverts it. He doesn't use his feelings for Rebecca as motivation to better himself, as the men in courtly romances do to make themselves more worthy of consideration and love, instead, he embitters himself over the fact Rebecca is not less than what she is.

He projects his lack of convictions onto her at every given opportunity. He wishes she had his same lack of chastity. He calls her own code of honor and dedication to her faith as a Jewish woman "stubbornness" and curses it. At the same time she lists off virtues he, as one sworn into a Christian institution, should have, such as charity toward the less fortunate and defending the innocent against falsehoods made against them, that as a man and a Christian, he is supposed to do these things without the expectation of personal gain. She tries to morally elevate him to her level (as she uses all the means and skills at her disposal to make the lives of even those who will always hate her for being Jewish a little easier and more comfortable), tries to give him a chance to live up to the purpose he proclaimed to the world on swearing to serve Christ as a knight, but he refuses these virtues because they do not gratify his desire for status or Rebecca herself.

I don't think this is an accident. Sir Walter Scott was a Romanticist and went through a lot of writings on the Middle Ages as reference material for Ivanhoe. He of all people would have an understanding of courtly love, and he decided Rebecca would be a more apt depiction of its ideals in her selfless and undemanding love for Wilfred than Bois-Guilbert could ever be in his desire for her.

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

#Abenteuer#Angelsachsen#Ivanhoe#Kreuzritter#Liebe#Locksley#Normannen#RichardLöwenherz#RobinHood#Turnier

0 notes

Note

Bois Guilbert seems like a Petyr Baelish + Sandor Clegane stand in .

Brian de Bois-Guilbert is like a combination of all the old dudes - false knights - girls predators of ASOIAF, he is also like Tyrion and Jorah.... ewww

He was the master mind behind De Bracy abducting Rowena; he abducted Rebecca himself and claimed to love her but he was the cause of her being accused of witchery and almost being burned alive....

He is the main villain of the story but of course GRRM loves him very much.... So much that he did a reinterpretation of Bois-Guilbert's sigil to gave it to House Corbray and he also have a House Corbray's sigil colored glass window at his home....

Lastly, he laid aside his shield, which had received some little damage, and received another from his squires. His first had only borne the general device of his rider, representing two knights riding upon one horse, an emblem expressive of the original humility and poverty of the Templars, qualities which they had since exchanged for the arrogance and wealth that finally occasioned their suppression. Bois-Guilbert’s new shield bore a raven in full flight, holding in its claws a skull, and bearing the motto, Gare le Corbeau.

—IVANHOE: A Romance

Coat of arms: Three black ravens in flight, holding three red hearts, on a white field (Argent, three ravens volant sable, each clutching in their claws a heart gules)

—House Corbray of Heart's Home

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prince John goes to the York household to bring the news of Rebecca's engagement to Sir Brian de Bois-Guilbert.

Set in the universe of the A&E 1997 minisseries.

@amalthea9 @incorrect-ivanhoe

@xenowlsome

#ivanhoe#ivanhoe 1997#my writing#fanfiction#brian de bois guilbert#rebecca of york#writers on tumblr#ciaran hinds#ciarán hinds#susan lynch

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Please sign my petition to cast this guy from the russian ‘tikhiy don’ series as Sir Brian de Bois-Guilbert

While we’re at it please also sign my petition for an Ivanhoe russian civil war AU

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

Ivan Kuskov has to answer for his crimes of 1) making me like brian de bois-guilbert from ivanhoe just with 2 illustrations, and 2) drawing athos Like That.

1) I have ah... a complicated relationship with Ivanhoe (no I don’t, I actually just hate that book but I suspect the Russian version was VERY ABRIDGED and possibly adapted as well as translated and I read it in the original Sir Walter Scott-ian version), but if you’re just gonna be like that, you have to show me the allegedly hot drawing!

2) Drawing Athos Like That is a crime against nature - but also what was he supposed to do? Alex went ON AND ON for PAGES about how BEAUTIFUL and NOBLE and CHIN OF BRUTUS and HANDS OF TITIAN PAINTINGS and BLAH BLAH ALL THE WOMEN WANT AND MEN ALSO WANT AND ALSO WANT TO BE. What was Ivan Kuskov to do, I ask you????

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

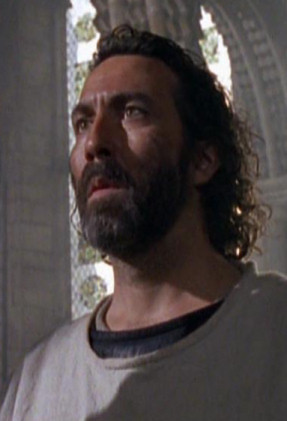

Dark side of the templar knight

Year 1997 , Sir Walter Scott's "Ivanhoe “- for those who've never opened Scott's book, "Ivanhoe" is three, four, maybe more stories in one. Underscoring all other threads is the uneasy alliance between Norman and Saxon.

Ciarán Hinds as the Templar Knight Sir Brian de Bois Guilbert in TV miniseries of Ivanhoe. Сharacter is a great, dark, menacing.

Hinds says screenwriter Deborah Cook "chose what to keep in and what to leave out" of Scott's vivid tale of medieval England. But he admits there's "a bit of me mixed in" to the complex character of Bois Guilbert.

And, at the heart of it all is the conflict between Ivanhoe and Bois Guilbert, who rode together beside Richard on the Third Crusade. Ivanhoe remained true to the king even in captivity; Bois Guilbert deserted them both and aligned himself with the power of the moment, John.

"(Bois Guilbert) started out a good man," Hinds says, "but he gave over to the darker side of it. He carried terrible resentment, and he took no prisoners. If it was a man, kill it; if it was a woman, shag it.”

The Knights Templar were supposed to be these noble holy men - monks - and we know, of course, that they really were greedy, misogynistic bastards.

"And what happens? Who finally gets to him? A Jew! And a woman!"

Hinds' scenes with that woman, Susan Lynch, who plays Rebecca to perfection, are some of the most emotionally charged of the six-hour series. It's only make-believe, after all, but the investment of emotional energy must be taxing.

"Exhausting," Hinds says, "but luckily Stewart (Orme, the director) gave us room to experiment. Susan's so young, but it works, don't you think?"

Beyond the mental and emotional demands of the roles were the physical ones, for the principals all did their own stunts, something that sounded frankly dangerous to us. But before we can say the word, Hinds fills in the blank: " 'Stupid' comes to mind," he says and laughs.

"It's what happens when you use what passes for a brain. But we had a great stunt coordinator, and the only thing we didn't do were the jousting scenes. That would have been beyond stupid - crass. You put on those helmets, and you can't see a thing."

"But actually, we were in this very complicated violent dance together (a broadsword fight to the death), and I heard this sound - just something not right, not metal on metal - and this feeling of horror came over me. And then a few moments later - you know you don't feel it right away - and Steven had this chunk of flesh out of his hand. But he mended quickly."

Source: Sun Herald

Author: Jean Prescott

Date: circa 1997

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sir Walter Scott introducing Brian de Bois-Guilbert: he was really sexy but also fucked up looking (only he takes several paragraphs to describe this)

casting director: so I’m thinking Ciaran Hinds then?

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ivanhoe

Sir Walter Scott. 1819. “Romanticism and Gothic” list.

“Rebecca and the Wounded Ivanhoe” by Eugene Delacroix.

“The knights are dust,

And their good swords are rust,

And their souls are with the saints, we trust.”

In the style of Sir Walter Scott, whose books and chapters open with epigraphs, I begin with a quote that Scott adapts from Coleridge’s “The Knight’s Tomb” (although in Ivanhoe we find this in the main body of the text).

The quote is just one of countless places where the narrator calls attention to the fact that the book is set in an earlier age (the reign of Richard I, in the 12th century) than its time of publication (1819). Whereas a contemporary historical novel typically presents a self-contained story, without extradiegetic references to its nature as a period piece, Ivanhoe scuttles between its setting and (Scott’s) present-day: for example, to contrast what a certain building looked like in the period with how it does now; or contrast the customs of the time with current customs, sometimes to help readers understand an event (“And as there were no forks in those days, his clutches were instantly in the bowels of the pasty”), sometimes just because; or offer reasons why we should believe in the plausibility of his fictions, naming his historical sources. As the first historical novelist, Scott seems to feel called upon to explain and justify his new genre even within the text itself. In their context, the Coleridge lines are trotted out to justify why the narrative declines to include lengthy descriptions of the devices and colors of the knights at a particular tournament—contrary, the narrator explains, to “my Saxon authority (in the Wardour Manuscript).”

Of course, no work of fiction needs to justify why it includes certain details and leaves out others—it is the author’s job to decide what material is relevant, and there are far too many choices involved to justify each one. But the narrator brings up his reasoning behind not describing knights’ heraldry—namely, because they’re all dead now—to play up the theme of nostalgia, a staple of the Romanticist movement. Not only are we, in the nineteenth century, looking back at knights (how nostalgic), but remember, readers, they no longer exist (aw!).

But the Romanticist project here is ambivalent, with the narrator both criticizing (explicitly) and glorifying (usually more implicitly) the Age of Chivalry. The narrator frequently opines on “the disgraceful license by which that age was stained,” and how “fiction itself can hardly reach the dark reality of the horrors of the period,” and so on. “In our own days...morals are better understood” (he’s no relativist). But on the other hand, as Richard the Lionheart comments upon hearing the Saxon noble Athelstane detail how he escaped from a crypt, “beshrew me but such a tale is as well worth listening to as a romance.” That’s because it’s a tale within a romance, and romances, the implied author seems to agree, are well worth listening to. “The horrors” are seductive. The horrors are romantic. (Cf. the Gothic.)

The title may be Ivanhoe, after its chivalric Saxon hero Wilfred of Ivanhoe, but the real hero(ine), arguably, is the beautiful and long-suffering Jewess Rebecca. Here we can see the real divergence of this 19th-century Romantic work from its medieval-romance inspiration. In what can be read as an implicit criticism of medieval romance and the age that gave rise to it, the show, I think, is stolen from the titular knight-errant by a Jewish woman.

The only character with no flaws or foibles, Rebecca is even more perfect than the heroine we would expect to star in this romance—Ivanhoe’s lady-love, the Saxon princess Rowena. As the similarity of their names suggests, Rebecca and Rowena are doubles. They appear in back-to-back chapters, simultaneously unfolding chapters that feature them, imprisoned in separate rooms of the same castle, spurning the sexual advances of their respective captors. Heroines locked up in castle chambers, besieged by would-be rapists and the threat of forced marriages; heroines demonstrating their noble character by rejecting wicked seducers—all tropes. Less predictable is the use of these tropes as a means of contrasting the situations of women from different classes, and with a Jewish woman emerging as the superior character, no less.

Both women do triumph in their goal of averting the fates their captors intend. But Rowena, normally haughty, crumples in a flood of tears when she realizes De Bracy’s power to force her hand in marriage. (Luckily for her, De Bracy is soft at heart—this would not have worked on Rebecca’s admirer, the still more wicked Brian de Bois-Guilbert.) Rebecca, though bearing herself with “courtesy” and a “proud humility” (in contrast to Rowena’s haughtiness), shows herself to have more spirit and strength of character. As a member of a despised race, Rebecca is approached with an offer far less honorable than marriage. (Also, Bois-Guilbert’s vows as a Knight Templar forbid his marriage to anyone.) Instead, the Knight wants to make her his mistress. In such a station she will be showered with riches and glory, he promises. She answers with true fighting words: “I spit at thee, and I defy thee.” In a classic (literally, going back to classical mythology) heroine move, Rebecca threatens to commit suicide, jumping to the ledge of the high turret and warning him not to come a step closer. This both dissuades Bois-Guilbert from his original intent and heightens his passion for her: “Rebecca! she who could prefer death to dishonor must have a proud and a powerful soul. Mine thou must be!...It must be with thine own consent, on thine own terms.”

Thus Rebecca finds herself at the center of a Gothic-heroine-threatened-with-rape-in-castle-chamber scene turned into a Samuel Richardson-style seduction narrative—that gives way, at this part, to a Gothic castle siege passage. Whereas Rowena’s persecutor uses the interruption presented by the siege as an excuse to desist in his ill-fated suit, the Richardsonian plot starring Rebecca continues as a dominating strand of the novel, another respect in which her character appropriates the literary territory of the highborn Englishwoman. Before Brian de Bois-Guilbert closes his first scene with Rebecca to go defend the castle, he established himself as that tantalizing character-type, the potentially reformable rake. “I am not naturally that which you have seen me—hard, selfish, relentless. It was woman that taught me cruelty, and on woman therefore I have exercised it...” He came home from knight-errantry, he explains, to find that the lady-love whose fame he spread far and wide had married another man. Here the reader can glimpse the possibility for Rebecca to be a Mary (another Jewess) to the former lady’s Eve, the means to redemption for a man who was led by a woman into corruption. Whether the Knight Templar will turn out like Richardson’s reformable Mr. B or the irredeemable Lovelace remains to be seen.

In another aspect of Rebecca’s and Rowena’s doubleness, Rebecca’s (rejected) lover is antagonist to Rowena’s (accepted) lover, the hero Ivanhoe. Brian de Bois-Guilbert is the ultimate 12th-century bad boy: he has “slain three hundred Saracens with his own hands,” and he slays with the ladies, too. He is described, in the Ann Radcliffe tradition, with all the dark fascination of a Gothic villain:

“His expression was calculated to impress a degree of awe, if not fear, upon strangers. High features, naturally strong and powerfully expressive...keen, piercing, dark eyes, told in every glance a history of difficulties subdued and dangers dared...a deep scar on his brow gave additional sternness to his countenance and sinister expression to one of his eyes...”

and so on. One of the most interesting things about the novel for me is the way that Bois-Guilbert—over and above whatever is appealing about bad boys—is a strangely sympathetic character, more so than Ivanhoe, and to what degree that was built into the narrative intentionally. When the narrator weighs in with moral judgments (as he often does), it can offer insight into what his take might be on those scenes unaccompanied by commentary. So for example, when the narrator calls “the character of a knight of romance” (here, describing King Richard) “brilliant, but useless,” it implies an author for whom Rebecca is a mouthpiece when she comes down on the anti-chivalry side of a debate with Ivanhoe. So the narrator—and most modern people—likely agree with Rebecca’s opinion of the laws of chivalry as “an offering of sacrifice to a demon of vain glory,” to which a highly miffed Ivanhoe responds that she can’t understand because she is not a noble Christian maiden (unlike Rowena, is the unspoken subtext).

Applying this to the case of Bois-Guilbert, the villain, we might conclude, to our confusion, that his views of race are closer to the narrator’s (more progressive). I have already discussed the novel’s treatment of Rebecca, one of two major Jewish characters; the other, her father Isaac, conforms to some offensive Jewish stereotypes (stingy, money-hoarding, obsequious etc.) but is ultimately portrayed as good-hearted. Moreover, anytime the narrator draws on negative stereotypes he accompanies it with vindications of the Jewish people based on their historic oppression. As in other areas, the storytelling is here flavored with a decidedly 19th-century sensibility (even perhaps progressive for 1819, when Jews still could not hold public office in England). The narrator repeatedly describes the anti-Semitism of his characters as “prejudiced” and “bigoted.” All the characters seem to feel Rebecca’s beauty and greatness, but Bois-Guilbert is the only one who sees her as an equal, without qualifying her noble traits in terms of her Jewishness. Her race seems to be a non-issue for him. Contrasted with Ivanhoe, whose admiring male gaze turns into a demeanor of cold courtesy when he learns Rebecca’s descent, the medieval villain looks more and more like a hero for the 21st century. Could he be Scott’s real hero?

Moving forward, the evidence piles in favor of Rebecca as the real star (despite her complete lack of mention on the back cover of my 1994 Penguin Classics edition). The penultimate chapter, the novel’s denouement, decides Rebecca’s fate in the Richardsonian narrative. The two chapters prior, separating the conclusion from when we last left Rebecca, in danger of being burned at the stake as a Jewish sorceress, are sort of like...okay, Ivanhoe, Rowena, Richard the Lionheart, blah blah blah. Every chapter in Ivanhoe is fun, and there’s a surprise in these chapters, but it’s ultimately an example of Scott’s mastery of the suspense trick of drawing out a cliffhanging moment by switching to a different plot, one that is slower and more predictable and less emotionally captivating. It’s all great reading, but whether or how Rebecca will be saved is what we really want to know, what we will read through anything to find out. Rebecca’s importance—and Rowena’s as her foil—is also borne out by Scott’s choice to close the novel on their farewell scene.

The penultimate chapter contains Rebecca’s trial by combat. Rebecca’s life is at stake, but the real trial is Brian de Bois-Guilbert’s. Since backing off the whole raping Rebecca idea, he has saved her life and then put it at risk again. Bois-Guilbert’s rescue of Rebecca from the burning castle of Torquilstone, by the way, is an example of Scott’s practically cinematic sense of humor and flair for dialogue. Essentially, the Knight Templar appears in the room where Rebecca has been nursing Ivanhoe, when they’re all about to go up in flames; Rebecca is more fiery than the fire (“Rather will I perish in the flames than accept safety from thee!”); Bois-Guilbert picks her up and carries her off anyway (“Thou shalt not choose, Rebecca; once didst thou foil me, but never mortal did so twice”); Ivanhoe, unable to move, yells hilariously impotent threats of rage from his sickbed: “Hound of the Temple—stain to thine order—set free the damsel! Traitor of Bois-Guilbert, it is Ivanhoe commands thee! Villain, I will have thy heart’s blood!” The perfectly timed next sentence: “‘I had not found thee, Wilfred,’ said the Black Knight, who at that instant entered the apartment, ‘but for thy shouts.’”

After this daring rescue, in which the Knight Templar uses his shield to protect Rebecca at the risk of his own life as they gallop on his horse through the flying arrows of the battle, he spirits her to the prefectory of his Temple with the purpose of keeping her captive until she feels forced to “consent” to sex with him. As one might expect in the case of two equally indomitable people with a difference in values, this isn’t going well, until it goes even worse: the Grand Master of the Knights Templar, a stickler for all those pesky rules about not drinking and fucking, makes a surprise visit and finds out about Rebecca. The leader of the prefectory, who knew about Rebecca and was cool with it but has to save face for himself and his most important Knight, convinces the Grand Master that the Jewess has literally bewitched Bois-Guilbert (an easy sell). So in all fairness, she should really be burned to death and he should be given a few Hail Marys. Learning of this horrific prospect, Bois-Guilbert returns to Rebecca with his final offer: he will leave England, abandoning the Knights Templar in all its attendant glory and ambitious prospects, in order to save her, on the condition that she accompany him to start a new life back in the Middle East, where he can conquer everything (his reigning passion) there instead; if not, he’s not giving up his whole life for nothing, and she will see that “my vengeance will equal my love.” For the third time, Rebecca’s answer is that she’d rather die. Bois-Guilbert despairs, wavers, makes a plot to save her without compromising his position—he gets her, when inevitably convicted, to request a trial by combat, imagining that he can be her champion in disguise. Then he is required to fight for the Knights Templar against her champion (if she can even find a champion). Brian de Bois-Guilbert is like the third best knight in the world, so that’s probably a death sentence for Rebecca. He offers to save her again when she’s at the stake, with no champion for her yet appearing and time running out, and is again rebuffed. Ivanhoe rolls up at the last minute to be Rebecca’s champion, still really wounded, and his horse is totally exhausted. Under these conditions, the Knight Templar knocks Ivanhoe off his horse, as everyone expects. But no one, not the live audience, certainly not me, expects Brian de Bois-Guilbert to fall off his horse for no reason, practically untouched, and die. The Grand Master says, “This is indeed the judgment of God.” True to genre, the narrator replaces divine intervention in human affairs with a very Romantic and scarcely more probable explanation: “he had died a victim to the violence of his own contending passions.”

Rebecca’s would-be seducer dies of being unable to decide whether he is a Mr. B or a Lovelace. Some readers may be left in similar indecision about how to judge him. Not so Rebecca, who has actually loved Ivanhoe the whole time, "imput[ing] no fault to [him] for sharing in the universal prejudices of his age and religion.” Rebecca is very unusual among Romantic heroines from the long 18th century in that her love goes unrequited. She may meet the type’s standards of perfection notwithstanding her Jewishness, but ultimately she cannot escape its limitations to claim her full literary-generic inheritance, the hero’s adoration. Happily ever after goes to the less deserving Rowena, and Ivanhoe only has the decency to recall Rebecca’s beauty and magnanimity “more frequently than [Rowena] might altogether have approved.” Rebecca must withdraw and devote her life to God. In this genre, there is no such thing as second love, and that is one of many points on which the narrator remains silent.

3 notes

·

View notes

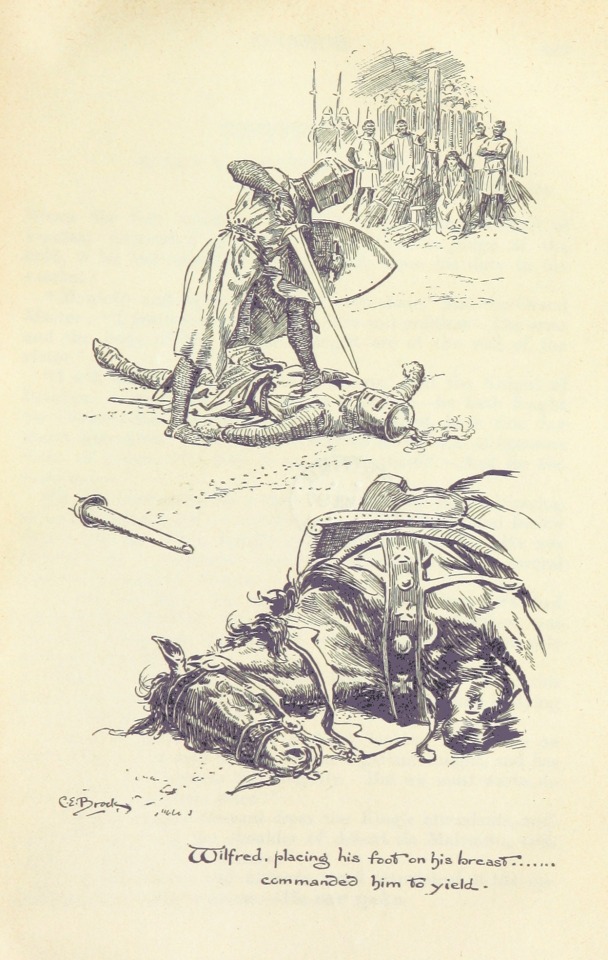

Text

#ivanhoe#wilfred of ivanhoe#sir brian de bois guilbert#brian de bois guilbert#duel#combat#joust#jousting#tournament#desdichado#knights#chivalry#chivalric#art#history#medieval#england#knight#middle ages#britain#sir walter scott#charles edmund brock#c.e. brock#romance#chivalric romance#europe#european

189 notes

·

View notes

Text

And so, the Swedish people gather in front of our televisions, as always on New Year’s Day, to refresh our national hate of Sir Brian de Bois-Guilbert, to the great bafflement of the esteemed Sam Neill, whose long and illustrious career has never been able to banish his reputation as “the villain of Ivanhoe”.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Rebecca Kidnapped by the Templar, Sir Brian de Bois-Guilbert, 1858, Eugene Delacroix

Size: 81.5x105 cm

Medium: oil, canvas

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

What is your opinion on the whole Aphmau not chosing Garroth thing?

I was perfectly fine with it. There has always been something about Garroth that rubs me the wrong way. He almost seems to live in his own little world where he just assumes the woman he loves will love him the same way. It didn’t seem like he could comprehend her loving someone else other than him and that was why he felt betrayed. I guess in a way his heart is in conflict with his duty. I actually have an opinion that Garroth would make a great villain like Brian de Bois-Guilbert whose passions for Rebecca ultimately resulted in him having a seizure and dying… It sounds better when Sir Walter wrote it. Aphmau had found a kindred spirit, someone who understood the hardships of being a leader and was a parent much like her. Garroth had run away from his responsibility as heir of O’Khasis and so never knew the hardships of being a leader and until Aphmau came about seemed to have lived a very celibate life. No, I do not believe Garroth being chosen by Aphmau would have been a good thing. Garroth is her right hand and Aaron was her heart.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Have you read sir Walter Scott's Ivanhoe? I always thought that Kylo resembles the main antagonist of the story, the Master of the Templar Knights Brian de Bois-Guilbert. I don't know if you've read the book, but I'm shocked why nobody in this fandom has drawn parallels between them, which are so obvious as if they used Brian as a template to write Kylo, especially regarding Brian's complexity and his capacity to love even though he commited terrible things.

No, I haven’t! That definitely sounds like an interesting parallel, though I’d be surprised if it were being intentionally referenced, given that Scott is considered quite old-hat and obscure now.

12 notes

·

View notes