#the 1619 project

Photo

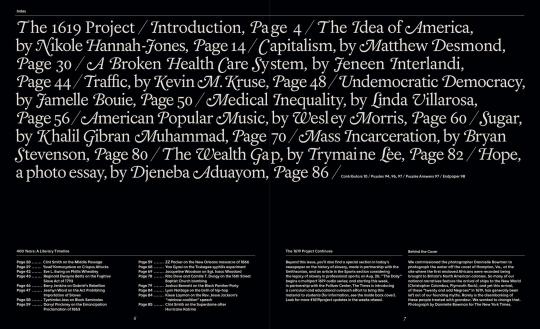

Ben Grandgenett / The New York Times Magazine / The 1619 Project – Index / Magazine / 2019

52 notes

·

View notes

Photo

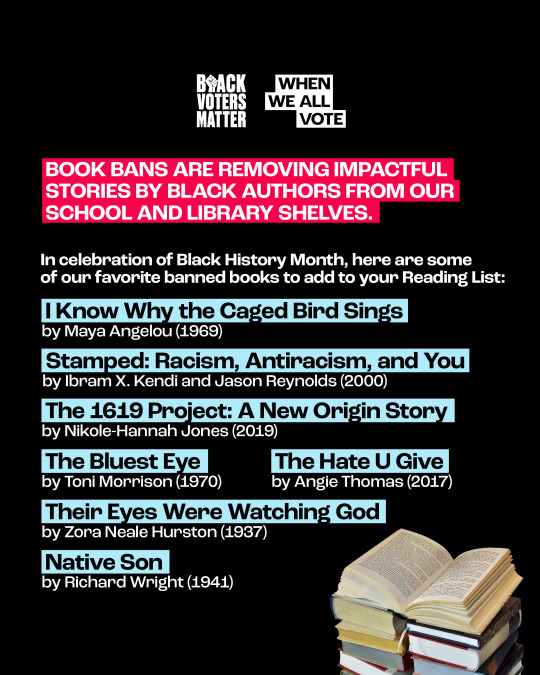

In collaboration with Black Voters Matter, we made this list of our 7️⃣ favorite books by Black authors being banned in schools and libraries across the country. Many of these helped to broaden America’s view of Black people, art, and culture.

Have you read any of these yet, and are any on your Reading List this year? Comment below with your favorites! 📚

#banned books#book bans#black authors#black history month#bhm#maya angelou#ibram x. kendi#jason reynolds#nikole hannah jones#toni morrison#angie thomas#zora neale hurston#richard wright#i know why the caged bird sings#stamped#the 1619 project#the bluest eye#the hate u give#their eyes were watching god#native son#booktok

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

4.1.24//4:11 p.m.

Life been lifein', but I'm here.

Protecting and healing my mind, listening to my body, reading more books, and loving on the people who matter a little harder. I hope everyone is well. 🦋

Current read: The 1619 Project by Nikole Hannah-Jones

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

In August of 2019, a special issue of the Times Magazine appeared, wearing a portentous cover—a photograph, shot by the visual artist Dannielle Bowman, of a calm sea under gray skies, the line between earth and land cleanly bisecting the frame like the stroke of a minimalist painting. On the lower half of the page was a mighty paragraph, printed in bronze letters. It began:

In August of 1619, a ship appeared on this horizon, near Point Comfort, a coastal port in the British colony of Virginia. It carried more than 20 enslaved Africans, who were sold to the colonists. America was not yet America, but this was the moment it began.

The name of this endeavor was introduced at the very bottom of the page, in print small enough to overlook: “The 1619 Project.” The titular year encapsulated a dramatic claim: that it was the arrival of what would become slavery in the colonies, and not the independence declared in 1776, that marked “the country’s true birth date,” as the issue’s editors wrote.

Seldom these days does a paper edition have such blockbuster draw. New Yorkers not in the habit of seeking out their Sunday Times ventured to bodegas to nab a hard copy. (Today you can find a copy on eBay for around a hundred dollars.) Commentators, such as the Vox correspondent Jamil Smith, lauded the Project—which consisted of eleven essays, nine poems, eight works of short fiction, and dozens of photographs, all documenting the long-fingered reach of American slavery—as an unprecedented journalistic feat. Impassioned critics emerged at both ends of the political spectrum. On the right, a boorish resistance developed that would eventually include everything from the Trump Administration’s error-riddled 1776 Commission report to states’ panicked attempts to purge their school curricula of so-called critical race theory. On the other side, unsentimental leftists, such as the political scientist Adolph Reed, Jr., accused the series of disregarding the struggles of a multiracial working class. But accompanying the salient historical questions was an underlying problem of genre. Journalism is, by its nature, a provisional and fragmentary undertaking—a “first draft of history,” as the saying goes—proceeding in installments that journalists often describe humbly as “pieces.” What are the difficulties that greet a journalistic endeavor when it aspires to function as a more concerted kind of history, and not just any history but a remodelling of our fundamental national narrative?

In the preface to a new book version of the 1619 Project, Nikole Hannah-Jones, a Times Magazine reporter and the leading force behind the endeavor, recalls that it began, as many journalistic projects do, in the form of a “simple pitch.” She proposed a large-scale public history, harnessing all of the paper’s institutional might and gloss, that would “bring slavery and the contributions of Black Americans from the margins of the American story to the center, where they belong.” The word “project” was chosen to “emphasize that its work would be ongoing and would not culminate with any single publication,” the editors wrote. Indeed, the undertaking from the beginning was a cross-platform affair for the Times, with special sections of the newspaper, a series on its podcast “The Daily,” and educational materials developed in partnership with the Pulitzer Center. By academic standards, the proposed argument was not all that provocative. The year 1619 itself has long been depicted as a tragic watershed. Langston Hughes wrote of it, in a poem that serves as the new book’s epigraph, as “The great mistake / That Jamestown made / Long ago.” In 2012, the College of William & Mary launched the “Middle Passage Project 1619 Initiative,” which sponsored academic and public events in anticipation of the approaching quadricentennial. “So much of what later becomes definitively ‘American’ is established at Jamestown,” the organizers wrote. But the legacy-media muscle behind the 1619 Project would accomplish what its predecessors in poetry and academia did not, thrusting the date in question into the national lexicon. There was something coyly American about the effort—public knowledge inculcated by way of impeccable branding.

The historical debates that followed are familiar by now. Four months after the special issue was released, the Times Magazine published a letter, jointly signed by five historians, taking issue with certain “errors and distortions” in the Project. The authors objected, especially, to a line in the introductory essay by Hannah-Jones stating that “one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery.” Several months later, Politico published a piece by Leslie M. Harris, a historian and professor at Northwestern who’d been asked to help fact-check the 1619 Project. She’d “vigorously disputed” the same line, to no avail. “I was concerned that critics would use the overstated claim to discredit the entire undertaking,” she wrote. “So far, that’s exactly what has happened.”

The pushback from scholars was not just a matter of factuality. History is, in some senses, no less provisional than journalism. Its facts are subject to interpretation and disagreement—and also to change. But one detected in the historians’ complaints a discomfort with the 1619 Project’s fourth-estate bravado, its temperamental challenge to the slow and heavily qualified work of scholarly revelation. This concern was arguably borne out further in the Times’ corrections process. Hannah-Jones amended the line in question; in both the magazine and the book, it now states that “some of the colonists” were motivated by Britain’s growing abolitionist sentiment, a phrasing that neither retreats from the original claim nor shores it up convincingly. In the book, Hannah-Jones also clarifies another passage that had been under dispute, which had claimed that “for the most part” Black Americans fought for freedom “alone.” The original wording remains, but a qualifying clause has been added: “For the most part, Black Americans fought back alone, never getting a majority of white Americans to join and support their freedom struggles.” As Carlos Lozada pointed out in the Washington Post, the addition seems to redefine the meaning of the word “alone” rather than revise or replace it. In my view, the original wording was acceptable as a rhetorical flourish, whereas the amended version sounds fuzzy.

In the book’s preface, Hannah-Jones doesn’t dwell, as she well could have, on the truly deranged ire the Project has triggered on the right over the past few years. (Donald Trump’s ignorant bluster is mercifully confined to a single paragraph.) But neither is she entirely honest about the scope of fair criticism that the work has received. She files both academic disagreement (from “a few scholars”) and fury from the likes of Tom Cotton under the convenient label “backlash,” and suggests that any readers with qualms resent the Project for focussing “too much on the brutality of slavery and our nation’s legacy of anti-Blackness.” (Meanwhile, even the five historians behind the letter wrote that they “applaud all efforts to address the enduring centrality of slavery and racism to our history.”) The editors of the book, who include Hannah-Jones and the Times Magazine’s editor, Jake Silverstein, want to “address the criticisms historians offered in good faith”; accordingly, they’ve updated other passages, including ones on Lincoln and on constitutional property rights. But even the use of the term “good faith” suggests a hawkish mentality regarding the revisions process: you’re either against the Project or you’re with it, all in. There is little room in a venue as public as the 1619 Project’s for the learning opportunities that arise when research sets its ego aside and evolves in plain sight.

As Hannah-Jones notes, the disagreements needn’t undermine the 1619 Project as a whole. (After all, one of the letter’s signatories, James M. McPherson, an emeritus professor at Princeton, admitted in an interview that he’d “skimmed” most of the essays.) But the high-profile disputes over Hannah-Jones’s claims have eclipsed some of the quieter scrutiny that the Project has received, and which in the book goes unmentioned. In an essay published in the peer-reviewed journal American Literary History last winter, Michelle M. Wright, a scholar of Black diaspora at Emory, enumerated other objections, including the series’ near-erasure of Indigenous peoples. Wright sees the 1619 Project as replacing one insufficient creation story with another. “Be wary of asserting origins: they tend to shift as new archival evidence turns up,” she wrote.

The Project’s original hundred pages of magazine material have, in the new volume, swelled to more than five hundred, and certain formatting changes seem designed to serve its “big book” aspirations. Lyrical titles from the magazine issue, such as “Undemocratic Democracy” and “How Slavery Made Its Way West,” have been traded for broadly thematic ones (“Democracy,” “Dispossession”) and now join sixteen other single-word chapter titles, such as “Politics” (by the Times columnist Jamelle Bouie), “Self-Defense” (by the Emory professor Carol Anderson), and “Progress” (by the historian and best-selling anti-racism author Ibram X. Kendi). Along with the preface and an updated version of the original ruckus-raising essay, Hannah-Jones has written a closing piece, cementing her role as the 1619 custodian. In the manner of an academic text, the Project is showier about its scholarship this time around, sometimes cumbersomely so, with in-text citations of monographs with interminable titles. New essays, by scholars including Martha S. Jones and Dorothy Roberts, pointedly bolster the contributions from within the academy. Perhaps also pointedly, endnotes at the back of the book list the source material, which the series in magazine form had been accused of withholding.

At the same time, many of the essays in the book remain shaped according to the conventions of the magazine feature. First, a contemporary scene is set: the day after the 2020 election; the day Derek Chauvin killed George Floyd on a Minneapolis street; Obama’s first campaign for President; Obama’s farewell address. Then there is a section break, followed by a leap way back in time, the sort of move that David Roth, of Defector, has called, not without admiration, “The New Yorker Eurostep,” after a similarly swerving basketball maneuver. For the 1619 Project, though, the “Eurostep” isn’t merely a literary device, used in the service of storytelling; it is also a tool of historical argument, bolstering the Project’s assertion that one long-ago date explicates so much of what has come since. Modern-day policing evolved from white fears of Black freedom. Slave torture pioneered contemporary medical racism. For each of those points a historical narrative is unfolded, dilating here and leapfrogging there until the writer has traversed the promised four hundred years and established a neat causal connection.

For instance, an essay by the lawyer and professor Bryan Stevenson traces the modern plague of mass incarceration back to the Thirteenth Amendment, which ended slavery but made an exception for those convicted of crimes. In his eight pages outlining the “unbroken links” between then and now, Stevenson breezes past the constellation of policies that gave rise to mass incarceration in the span of a single sentence—“Richard Nixon’s war on drugs, mandatory minimum sentences, three-strikes laws, children tried as adults, ‘broken windows’ ”—and explains that those policies have “many of the same features” as the Black Codes that controlled freed Black people a century and a half ago. (The language here has been softened: in his original magazine piece, Stevenson deemed the Black Codes and the latter-day policies “essentially the same.”) It is not an untruthful accounting but it is an unstudious one, devoid of the sort of close reading that enlivens well-told histories. Alighting only so briefly on events of great consequence, many of “The 1619 Project” contributions end up reading like the CliffsNotes to more compelling bodies of work.

At its best, the book’s repetitive structure allows the stand-alone essays to converse fruitfully with one another. Matthew Desmond, explaining the origins of the American economy, describes the lengths the Framers went to secure the country’s chattel, including by adding a provision to the Constitution granting Congress the power to “suppress insurrections.” The implications of that provision and others like it are explored in the essay “Self-Defense,” by Anderson, whose note that “the enslaved were not considered citizens” acquires richer significance if you’ve read Martha S. Jones’s preceding chapter on citizenship. But the formula wears over time. With few exceptions—among them, a piece by Wesley Morris, a masterly stylist—the voices of the individual writers are unrecognizable, hewn to flatness by the primacy of the Project’s thesis. Regretfully, this is true even of the book’s poems and short fiction, which, in a rather utilitarian gesture, are presented between chapters along with a time line that aids the volume’s march toward the present.

For instance, the book’s very first listed event—the arrival of the White Lion in August, 1619—is followed by a poem by Claudia Rankine, which sits on the opposite page and borrows its name from that ship: “The first / vessel to land at Point Comfort / on the James River enters history, / and thus history enters Virginia.” A short piece by Nafissa Thompson-Spires depicts the interior monologue of a campaigner for Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman to run for President, after Chisholm decided to visit George (“segregation forever”) Wallace in the hospital following an assassination attempt in 1972—a visit noted in a time line on the preceding page. As in much of the other fiction in the volume, Thompson-Spires’s prose is left winded by the responsibilities of exposition: “It seemed best not to try to convert the whites but to instead focus on registering voters, especially older ones on our side of town, many of whom, including Gran and PawPaw, couldn’t have passed even a basic literacy test.”

The didacticism does let up on occasion. An ennobling found poem by Tracy K. Smith derives its text from an 1870 speech by the Mississippi Senator Hiram Rhodes Revels, the first Black member of congress, who, a month after his swearing in, had to argue to keep Georgia’s duly elected Black legislators, who’d been denied their seats by the Democrats. (“My term is short, fraught, / and I bear about me daily / the keenest sense of the power / of blacks to shed hallowed light, / to welcome the Good News.”) A poem by Rita Dove channels the antsiness of Addie, Cynthia, Carol, and Carole, the four children who perished in a church bombing in Birmingham on September 15, 1963: “This morning’s already good—summer’s / cooling, Addie chattering like a magpie— / but today we are leading the congregation. / Ain’t that a fine thing!” But, on the whole, the literary creativity fits awkwardly with the task of record-keeping. It is a shame to assemble some of the finest and most daring authors of our time only to hem them in with time stamps.

So what are the facts? There are plenty in the volume that aren’t likely to be disputed. In the late seventeenth century, South Carolina made its whites legally responsible for policing any slave found off of the plantation without permission, with penalties for those who neglected to do so. In 1857, the Supreme Court decided against Dred Scott, ruling that Black people “are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word ‘citizens’ in the Constitution, and can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides.” In 1919, the U.S. Army strode into Elaine, Arkansas, and gunned down hundreds of Black residents. In 1960, Senator Barry Goldwater mourned the decline of states’ rights heralded by Brown v. Board of Education, contending that protecting racial equality was not federal business. In 1985, six adults and five children in Philadelphia received “the commissioner’s recipe for eviction,” as Gregory Pardlo writes in a poem, including “M16s, Uzi submachine guns, sniper rifles, tear gas . . . and one / state police / helicopter to drop two pounds of mining explosives combined with two / pounds of C-4.” In 2020, Black Americans were reportedly 2.8 times more likely to die after contracting covid-19. What the 1619 Project accounts for is the brutal racial logic governing the “afterlife of slavery,” as Saidiya V. Hartman has put it in her transformative scholarship (which is referenced only once in this book, in an endnote, but without which a project such as 1619 might very well not exist).

The book’s final essay, by Hannah-Jones, argues in favor of reparations so that America may “finally live up to the magnificent ideals upon which we were founded.” By “we” here she is referring to the nation as a whole, but embedded in Hannah-Jones’s vision is a more provincial collective identity. The convoluted apparatuses of anti-Black racism don’t spare individuals based on the specifics of their family trees. Black Americans encompass those whose roots in this country date back for many generations, or for one. Yet Hannah-Jones’s unstated but unsubtle suggestion is that a particular subset of Black people, namely those of us who can trace our ancestry to slavery within the nation’s borders, are the truest inheritors of America, both its ills and its ideals. We represent the country’s best “defenders and perfecters,” are “the most American of all,” and are not “the problem, but the solution.” These dubious honors are pinned, like badges of pride, at the volume’s beginning and end, and, for me, the imposition of patriotism is more bothersome than any debated factual claim. In spite of all of the ugly evidence it has assembled, the 1619 Project ultimately seeks to inspire faith in the American project, just as any conventional social-studies curriculum would.

This faith finds its most sentimental expression in another new book about 1619, “Born on the Water,” which was co-authored by Hannah-Jones and Renée Watson for school-aged readers. Beautifully illustrated by Nikkolas Smith, it centers on a young Black girl’s familiar dilemma during a classroom genealogy assignment—what knowledge does she have to share about an ancestry that was torn asunder by the Middle Passage? One answer comes on the story’s final page, in which the girl is seated at her desk, smiling, her hands poised midway through crayoning stars and stripes for “the flag of the country my ancestors built, / that my grandma and grandpa built, / that I will help build, too.” Here the 1619 Project has left the genres of journalism and history for the realm of fable. But a similar thinking resides at the center of the 1619 Project in all of its evolving forms—past, present, and future, arranged in a single line.

#the 1619 project#nikole hannah-jones#lauren michele jackson#us history#LMJ is such an incredible thinker/writer and this essay always makes me mad about the relative paucity of the rest of the discourse#around the 1619 project#everything getting swept up into our endless culture war debates robs us of real thoughtful scholarship and cultural criticism#also this reminds me that I still need to read her book it's been on my list for years now

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Corn-based and leafy green–intensive Indigenous diets fused with African American cooking that relied on sweet potatoes, black-eyed peas, and pork to form a fundamental part of Southern regional culinary culture. Black women became expert basket weavers, most notably along the Carolina and Georgia coasts, using Native American plant preferences, even as Black men likely learned to build dugout canoes from Indigenous men. Enslaved Black people used local plants as herbal medicines in accordance with Indigenous knowledge, and both groups developed a rich and perhaps mutually informed folklore centering on trickster rabbit stories. Enslaved Black and Native Americans produced a distinctive pottery style known by archaeologists as colonoware. Many of these earthen vessels, which have been discovered on Virginia, South Carolina, and Georgia estates, are marked with hybrid circle and cross symbols believed to be reflective of West African, Native American, and Christian religious beliefs.

— Tiya Miles, The 1619 Project, “Dispossession”

#quotes#tiya miles#the 1619 project#first nations#indigenous people#black history#history#food#southern food

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

“It’s a perfectly rigged system,” she said, one maintained by manufactured inertia, the embrace of glacial progress, and illusions of inclusion.

Yes, King said, “justice delayed is justice denied,” and much of America said, “Great idea!”

Much of white America is “progress obsessed,” Hannah-Jones said. The response to questions about inequality’s stubbornness is, “We are making progress.” African Americans are expected to wait indefinitely for freedoms other groups in our society enjoy.

The phrase “we are making progress” drains any urgency and allows for mere pantomime of social justice concern.

“If we’re making progress, then we don’t actually have to do anything,” she said.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The 1619 Project" docuseries

#The 1619 Project docuseries#The 1619 Project#American history#Black history#Black American history#Nikole Hannah-Jones#a beautiful and thoughtful documentary honoring Black Americans#Black American

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Most schoolchildren are taught the Declaration of Independence’s most famous lines:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

But relatively few children or adults today are as familiar with the right to revolt that follows:

“Whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it…. When a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.”"

Nikole Hannah-Jones, The 1619 Project, Chapter 4, p. 131

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

If we are truly a great nation, the truth cannot destroy us.

The 1619 Project by Nikole Hannah Jones

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

BTS of The 1619 Project.

Nikole Hannah-Jones, Roger Ross Williams, and Nile Rogers.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Official Trailer For Hulu Original Docuseries ‘The 1619 Project’ From Lionsgate and Pulitzer Prize-Winning Journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones To Premiere Thursday, Jan. 26, 2023

Official Trailer For Hulu Original Docuseries ‘The 1619 Project’ From Lionsgate and Pulitzer Prize-Winning Journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones To Premiere Thursday, Jan. 26, 2023

Disney’s Onyx Collective announced a Jan. 26 premiere date for Hulu’s upcoming six-part limited docu-series “The 1619 Project,” an expansion of “The 1619 Project” created by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones and The New York Times Magazine. The limited series will debut with the first two episodes streaming exclusively on Hulu, with two additional episodes released every…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Everyone. Every single person should watch The 1619 Project.

1 note

·

View note

Text

#ginny and georgia#ginny miller#antonia gentry#ann petry#the street#audre lorde#sister outsider#nikole hannah-jones#the 1619 project#black lit#black history month

0 notes

Text

2024 Cinema Eye Honors: 'The 1619 Project,' 'Nothing Lasts Forever' Top Broadcast Nominations

View On WordPress

#32 sounds#american symphony#cinema eye honors#little richard: i am everything#smoke sauna sisterhood#still: a michael j. fox movie#the 1619 project

0 notes

Text

Hulu's docu-series "The 1619 Project" (January 26, 2023—February 9, 2023).

#Hulu#Docu Series#Documentary#The 1619 Project#History#Black History#American History#Nikole Hannah Jones#New York Times#NYT#2023#2020s

1 note

·

View note