#the tain

Text

Cú Chulainn, the nation’s babygirl

#cu chulainn#irish mythology#the tain#an táin#irish folklore#irish myths#celtic mythology#irish#cú chulainn

172 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I just got to the combat of Cú Chulainn and Fer Diad and I'm not doing well :_)

This is still very rough, and only half of it, but my interpretation of "Then they came up to each other and each put an arm around the other's shoulders, and gave him three kisses."

Now have to animate Cú Chulainn returning the kisses and clean it up! I have no idea when I will finish this, so enjoy for now <3

#animation#tain bo cuailnge#cu chulainn#ferdiad#fer diad#the tain#an tain#irish folklore#irish mythology#art#animatic#fanimation#fanimatic#ferdia#why so many spellings#sissiarte

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Boiling-Away of Young Cú Chulainn's Wrath

"He was placed in three vats of cold water to extinguish his wrath; and the first vat into which he was put burst its staves and its hoops like the cracking of nuts around him. The next vat into which he went boiled with bubbles as big as fists therefrom. The third vat into which he went, some men might endure it and others might not. Then the boy's wrath went down" (Dunn verses 77-79).

An old sketch of the young Cú Chulainn sitting miserably in the boiling vat which drowned his wrath.

One day I would like to produce a high-quality illustrated edition of the Táin Bó Cúailgne after the fashion of an Arthur Rackham gift-book. Rather an ambitious project.

#cu chulainn#cuchulainn#cu chulain#Irish mythology#tain bo cuailgne#the tain#red branch cycle#ulster cycle#setanta#changeling

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Táin Bot prompted some off-the-cuff TBC analysis just now, so I figured I'd paste the thread below so that it's backed up if Twitter disappears, and so youse can read it regardless of whether or not you're on the bird app. This is mostly exactly as it is on Twitter, except that I added the bit about O'Rahilly's translation, since I had space to do so:

'Daltán' is a diminutive of 'daltae': pupil, disciple, foster-child, ward, etc. So eDIL translates it as 'A little foster-child, a pupil; a term of endearment'. Why would Cú Chulainn use this term for Láeg, who is probably older than him?

Remember, this is the same recension of the Táin where Cú Chulainn repeatedly calls Láeg 'a phopa', a term of respect and endearment derived from 'father', usually used for an elder or a social superior.

(I talked about this a bit in my Oidheadh Con Culainn article.)

In this scene, Láeg has just described an Otherworldly being approaching them (Lug, in Recension 1, but he's not named in the Book of Leinster), and gone, "It's kinda weird, it's like nobody can see him even though he's walking straight past them."

Cú Chulainn responds with the line above -- essentially, "Yep, that would be because he's from the Otherworld." In O'Rahilly's translation, this is a little clearer as the meaning, I think: ‘That is true, my fosterling,’ said he. ‘That is one of my friends from the fairy mounds coming to commiserate with me.’ ('That is true' rather than 'In sooth' sounds both more like something an actual human would say, and also makes it clearer that he's agreeing with Láeg's understanding of events.)

So maybe the use of daltán is sarcastic, because he's pointing out something that seems obvious to him. Or it's genuine -- he's explaining something (Otherworld beings are only visible to the people they choose to show themselves to and/or you're a freak with the ability to see through their illusions, Láeg), so he's positioning himself as a teacher. Watch and learn, kid!

Dunno. Láeg's age is never confirmed, but he's almost certainly Cú Chulainn's elder, whether by a few months or by several years. That might be why Cú Chulainn calls him 'a phopa', possibly evoking an 'older brother' type fosterage relationship -- big bro Láeg.

(Again: I briefly discussed the evidence for considering Láeg to be Cú Chulainn's foster brother in my Oidheadh Con Culainn article, although I hope to write about that at more length some day. That's the article published in Quaestio Insularis, ftr.)

The use of 'a phopa' is still unusual, since it's usually used for a social superior, which Láeg certainly isn't. 'A daltán', in that regard, cleaves more to the expected hierarchies, but in the context of their wider relationship in this text, I feel it has to be sarcastic.

In fact, in Recension 1, Láeg takes on more of an advisory/teacher role himself, including giving legal advice to Cú Chulainn. I have an article about THAT coming eventually too, though it's still in peer review right now.

Regardless of the exact meaning or the vibes here, I think that it's definitely a term of endearment, as eDIL says. These two are always calling each other by nicknames and diminutives, and it's one of the reasons I find their relationship so interesting to explore.

This has been: off-the-cuff medieval Irish discussions with your host, Finn Longman. Tune in next time An Táin Bot shows up on my feed with a line that I have feelings about, for more unsolicited opinions.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

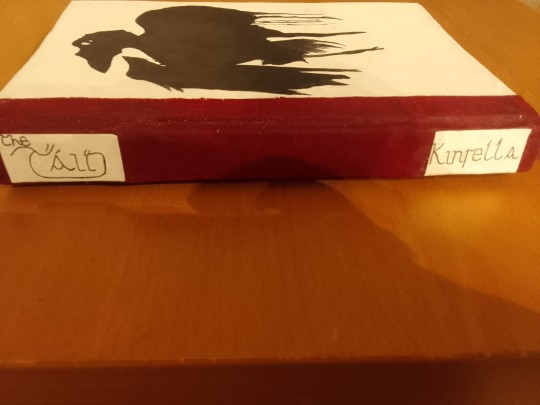

The Táin rebound as a hardback book

The Táin Bó Cuailgne (TBC) is an 8th Century Old Irish story. It is considered the closest thing in early Irish literature to a "national epic". It's central to the Ulster Cycle body of stories. The story centres on a war between the kingdoms of Connacht and Ulster over the Donn Cuailgne, a bull which seems to have magical or supernatural significance.

My old paperback copy was getting pretty worn from being read over and over! I decided to make a new hardback binding for it. Paperback books will never have the same lifespan as hardbacks unfortunately, but this should make the book last longer too. This edition is the famous Thomas Kinsella translation of 1969. I decided that it should be bound in red, white and black, as these appear several times in the text. This is most notable in the story of the Sons of Uisliu:

I copied the image on the cover from the original arrwork by Louis LeBrocquy. It depicts the Morrigan in crow form. She is a war goddess who manipulates other characters to her own ends throughout the story.

The title design on the spine is a bit abstract; the T and N are supposed to resemble bulls. This reflects one of the last episodes in the story, in which the Donn Cuailnge fights his Connacht counterpart, Findbennach.

The back cover contains a quote from the prophet Fedelm. She prophesies the outcome of the war to the Connacht queen Medb; needless to say, her prediction of disaster comes true. The quote is in both the original Old Irish and in English translation.

I also made homemade headbands and a ribbon bookmark.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

In contrast to the Hound; Candlelit Tales is doing an absolutely spectacular (so far, only a few episodes in) retelling of the Táin from multiple perspectives. I think the writing of these mythic figures is done really well without changing how the story is fundamentally built. I think it does a great job of presenting how a group of people, or an individual, not very dissimilar from how we are now, would behave in the situation. The multiple perspective for different parts of the story really lets them showcase a wide range of thoughts, feelings, and actions.

I don't remember who I saw on here mention it, but damn I'm glad I actually took the time to check it out.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cú Chulainn: *falls down the stairs*

Ferdiad: Are you okay?

Emer: Stop falling down the stairs!

Morrigan: How’d the ground taste?

#mythology#celtic mythology#irish mythology#celtic gods#celtic goddess#irish gods#irish goddess#ulster cycle#the tain#the táin#cú chulainn#cu chulainn#setanta#ferdiad#emer#morrigan#cú chulainn x ferdiad#cu chulainn x ferdiad#setanta x ferdiad#ferdiad x cu chulainn#ferdiad x cú chulainn#ferdiad x setanta#cú chulainn x emer#cu chulainn x emer#setanta x emer#emer x cu chulainn#emer x cú chulainn#emer x setanta

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

cu chulainn halfway through the táin, with no explanation whatsoever:

71 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cú Chulainn from the Tain is an Avatar of the Flesh.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

"They were brothers of one blanket" and "Loeg needs to help him prepare his special weapon" are two quotes that only make sense in Celtic lit class

#the tain#cu chulainn#fer diad#irish patrochilles#how do i keep a straight face in class?#spoiler i dont

1 note

·

View note

Text

they may be doomed by the narrative but atleast they had gay sex

39K notes

·

View notes

Text

#irish mythology#amylouioc art#artists on tumblr#illustration#irish folklore#celtic mythology#irish myths#Cú Chulainn#cu chulainn#the hound of ulster#Ulster cycle#the tain#tain bo cuailnge

294 notes

·

View notes

Text

Living among the Federation has made you woke Garak

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

So much of Garak as a person starts to make sense once you know his childhood was a fucking gothic novel. His main playground was a graveyard and he'd play pretend by perfoming improv eulogies to an imagined audience. For a long time his main touchstone for most important figures from recent history is 'oh yeah I know about that guy my dad buried him. great flower arrangements for that one'. He finds out later his 'parents' are actually a brother and sister who had to get married to avoid the utter shame and social devastation of having a child born out of wedlock, and they live in the basement of his biological father's house. (the madwoman in the attic vs. the tiny elim in the basement.) His biological father calls himself his uncle and locks him in a closet whenever he fails to live up to his insane and unpredictable expectations and everyone just has to act like that's normal and expected, and his will hangs over everything at all times, unseen but always felt keener than anything else. The father who actually raised him grows the world's most beautiful (and as it turns out, most poisonous) orchids and keeps the mask of a god hidden in a box in his work shed. Everyone in the house is choking down secrets like it's the only air they know how to breathe anymore.

What I'm saying is that right from the get-go this guy never had the faintest shot at turning out normal, so I'm glad that by middle age he's found a way to get a bit silly with it as he continues to be deeply deeply not normal about anything ever <3

#guess who's reading a stitch in time!#star trek ds9#elim garak#a stitch in time#star trek#ds9#I will make a monster post of asit thoughts eventually but just. jesus christ!!! what a start in life lmao#tolan and tain seem to have been... well not exactly friends probably but to have had some connection beforehand#did tain know him or mila first??? how was mila and tolan's sibling status presumably not known publicly?#at what point during all of that did tain start to have sex with tolan's sister. the more you think about it the more fucked it gets lol#under the circumstances... shoutout to tolan and mila for not leaving him somehow even more fucked up interpersonally than he is#and no thanks to tain for anything ever I hate him so much

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

All right, time to talk about the Maines. I apologise that this is so delayed -- I've had terrible pain-related brain fog lately, but today I can at least think, even if I'm typing this from bed because sitting up at a desk is Bad.

A couple of weeks back, a friend sent me this AskHistorians question:

This is very much my area of expertise, but I don't use Reddit, so I said I'd answer it here, for the benefit of @llwhn (and anyone else who is interested).

First of all, context: I published an article about the seven Maines in Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies 83 last year, which is one of the only pieces of research published on the topic in recent years. Unfortunately, I can't share this article online due to the copyright restrictions of the journal, but it's my research there that I'm drawing on. The Maines are a complicated bunch -- although we're told there are seven of them, they actually number between six and eight in any given list, and their names vary noticeably.

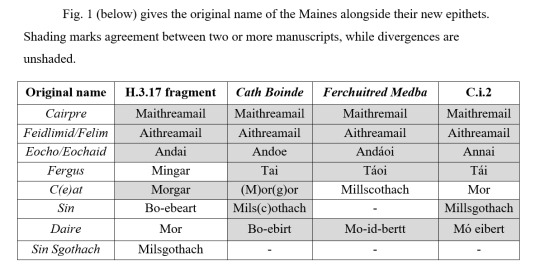

To show how much they vary, let me show you the table I produced for my CMCS article:

As we can see here, there’s considerable variation in a) how many of them there are, b) what their names are, and c) what order the names are in. This last point might not seem important, but it’s going to come up later.

Now that we’ve had a chance to appreciate that the ‘seven’ Maines are a far more complicated bunch than they appear, let’s get down to the specifics of your question. You wanted to know whether Maine Cotagaib-Uile’s epithet is implying that he’s nonbinary (or perhaps intersex?), especially as it talks about inheriting traits from both parents. This is a really interesting question, and not one I’d thought about before – surprising, since I also work on queer readings of medieval Irish texts. Having thought about it for a while, I don’t think that’s what’s being suggested here, but let’s look at it in more depth.

‘Cotagaib-Uile’ is probably the epithet to have received the most attention of those in this list, although given how little has been published about the seven Maines, that isn’t saying too much. This is interesting, because as you can see, it’s not in all of the lists, and some of the omissions are significant.

Quick Maine backstory: in some traditions, we’re told that the Maines originally had different names, and were renamed because of a prophecy Medb was given that her son Maine would kill Conchobar. She had no sons called Maine, so she renamed all of them (and one of them ends up killing a Conchobar, but not the one she wanted dead). This story is found in Cath Boinde / Ferchuitred Medba, as well as in a couple of manuscript fragments by itself; the first four columns of the table above show the lists of names given there.

In fact, let’s have another table, this time showing the ‘original’ names of the Maines and the epithets they were given when renamed, according to these four manuscripts:

Yep. As we can see, these manuscripts can’t agree on anything, which is funny, since they’re all versions of the same text. It just goes to show what a complicated question the Maines’ epithets offer. The fact that Cotagaib-Uile isn’t in this list is interesting, though, because some scholars have attributed quite a lot of importance to this name.

Introducing: Sir John Rhys. John Rhys was the Jesus Professor of Celtic at Oxford in the 19th century, and yet despite this distinguished academic background, managed to write a lot of absolute nonsense. That’s the 19th century for you! Rhys has the dubious honour of at least being creative in his wildly unsupported arguments; I love the confidence with which he’ll assert “this undoubtedly means X” when there is definitely a great deal of doubt and in fact it almost definitely doesn’t mean X.

Rhys is, however, one of the only people apart from me to have spent much time looking at the names of the Maines, so I was forced to consider his arguments for a while when I was writing this article. As we’ve seen above, there are often more than seven Maines, and Rhys, who had a theory that the “secht Maine” represented the days of the week (“sechtmain”), was keen to understand why there might be eight of them. He said that the epithet ‘Condagaib-Uile’ should be read as suggesting that this Maine ‘contained or comprehended all the others’. In this way, he’s functioning as a ‘superlative eighth’ to the seven – all the others are contained within him, just as sometimes triads give three examples of something and then a fourth that’s better than all of them.

But that’s not what the explanation given in Táin Bó Cúailnge suggests it means, is it? Now, I’ll note that Faraday’s translation is pretty old, and I wouldn’t generally use it. However, I pulled out Cecile O’Rahilly’s translation of the same line, and it’s pretty similar:

‘Their names are Maine Máthramail, Maine Aithremail, Maine Mórgor, Maine Mingor, Maine Mo Epirt, who is also called Maine Milscothach, Maine Andóe and Maine Cotageib Uile—he it is who has inherited the appearance of his mother and his father and the dignity of them both’

Cóir Anmann, a treatise on names, gives an explanation that seems to encompass Rhys's interpretation while saying the same thing as TBC:

‘who includes them all’, ‘i.e. had the appearance of his mother and father. For he was like them both’ (trans. Sharon Arbuthnot)

It's clear that even when Cotagaib-Uile is referring to "them all", it's not quite in the manner that Rhys argued, so his interpretation isn't particularly convincing. (He also attributed a lot of important to Cotagaib-Uile being the last in the list, which we can see very clearly from the table above is not always or even mostly the case.)

Instead, it definitely seems to be the “appearance” of both mother and father that the text claims Maine has inherited. Let’s look closer at that, because we don’t want to be misled by translations. Faraday uses ‘form’ instead; the difference there is negligible, but it might be significant, if we’re trying to read into this regarding gender and bodies.

The Irish word in TBC is ‘cruth’ meaning form, shape, appearance; beauty of form, shapeliness. It does refer to physical appearance, but it doesn’t seem to be a particularly gendered term referring to physical traits. There is no evidence, for example, that this is implying an intersex body containing both male and female traits. The simplest way to read this is just “he looks like both his parents”, which is a normal thing to say about somebody.

Moreover, it’s worth considering this name in the context of two of the other Maines in the list:

Aithremail, ‘like his father’, ‘i.e. he was like his father, i.e. like Ailill son of Máta’

Máithremail, ‘like his mother’, ‘i.e. he was like his mother, i.e. like Medb daughter of Eochaid’ (again from Cóir Anmann, translated by Sharon Arbuthnot)

If one brother takes after their father, one takes after their mother, then suggesting that a third brother might take after both of them doesn’t seem like a particularly loaded statement.

Indeed, if it was a loaded statement, we would expect these Significantly Gendered Traits to show up somewhere else. After all, Maine Mingar and Maine Mórgar get a whole story in which the “duty” (gar) of their names is positioned as central – that’s Táin Bó Regamain. So we might think there was a story in which taking after Medb or Ailill was significant, but there’s certainly no surviving story in which that happens.

That doesn’t mean there never was a story in which that aspect of their epithets was emphasised, but although Maine Mathremail and Maine Athremail are present in every list (a rarity among the Maines), I’m not aware that they ever get to take a starring role in any text that survives today. Likewise, there isn't a story in which Cotagaib-Uile’s superlative or combinatory nature is foregrounded.

All of that is a very long winded way of saying that I don’t think they are implying anything about this Maine’s gender: I think they’re simply saying that he has inherited traits from both Medb and Ailill. Since Medb is notorious for behaving in an “unwomanly” manner by trying to lead armies into war and so on (something some medieval authors were not impressed by), this also probably isn’t suggesting any of those traits were especially feminine.

But. That doesn’t mean this epithet, and the textual explanation given for it, doesn’t create space for a nonbinary reading of Maine. I’m all in favour of exploring queer possibilities regardless of the authors’ intentions. I think it would be challenging to argue for a trans reading overall simply because Maine Cotagaib-Uile does nothing else in the text except be included in this list, and therefore has no personality or behaviours to draw on, but that doesn’t mean you couldn’t choose, in your own creative or exploratory works, to explore nonbinary possibilities.

Moreover, although I don’t think this Maine is being portrayed as ambiguously gendered on purpose, Táin Bó Cúailnge is not a text where gender binaries are neatly demarcated and always maintained. Crucially, Cú Chulainn himself is a deeply ambiguous figure whose masculinity is constantly questioned, undermined, and problematised by those around him, and his own behaviour challenges their assumptions and their definitions of 'man'.

As people who follow me here know, I have an article which will be available in the next month or two about the ambiguities of Cú Chulainn’s gender and what this says about TBC as a text. I tend towards a transmasculine reading, and suggest one in this article, but that’s certainly not the only possibility. The value of queer and gender theory is that once you start dismantling assumptions about gender in this story, you can have a lot of fun looking at how it’s actually being constructed, rather than just how we assume it’s being constructed.

So I definitely think there’s potential for exploring more facets of gender in TBC than the ones that have already been discussed (by me or by others). And perhaps looking at epithets like this and what they tell us about personalities, appearances, and gender would be a good place to start – because clearly, medieval authors didn’t think it remarkable that a son could inherit the appearance or nature of his mother, or neither Maine Mathremail nor Maine Cotagaib-Uile would have the epithets that they do.

tl;dr: This passage in Táin Bó Cúailnge is probably not implying that the character in question is nonbinary, but there is lots of space for queer readings of this text.

For further reading on the seven Maines and the meaning of their epithets, you might enjoy my CMCS article; there’s a link on my website, which is also where I will also upload the article about Cú Chulainn and gender as soon as it’s available.

I hope this has been useful/informative, and I’m sorry it took me so long to get to it!

#6-8 assorted maines#tain bo cuailnge#the tain#the seven maines#medieval irish#ulster cycle#ask historians

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

the imperial accountant baru cormorant, and the duchess of vultjag

#the traitor baru cormorant#the masquerade#baru cormorant#tain hu#my art#fan art#character design#i recently rediscovered my literacy#so i read this whole series in two weeks and i think it's both kinda phenomenal and very flawed#but fundamentally just very interesting in almost every aspect#i had a great time#not gonna apologise for the niche fan art lol#utterly obsessed with baru btw#character of all time

2K notes

·

View notes