#thirteenth amendment

Text

I need people to understand that slavery is still legal in the US. The thirteenth amendment, which is supposed to be the one that abolished slavery, says this:

“except as punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted”

It just isn’t legal to do it outside of punishment from the legal system.

This is part of why the imprisoned can’t vote, part of why black people have such high rates of conviction, part of why punitive, punishment-focused culture is so pushed in america. They want more slaves.

People in prison are forced to do highly dangerous jobs, such as firefighting, for literally pennies. Not even joking.

If you are wondering how it was constitutional for Asian Americans to be forced to produce for the military during WWII’s Japanese internment camps, this is how. And if you didn’t know that that happened in the first place, well now you do

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

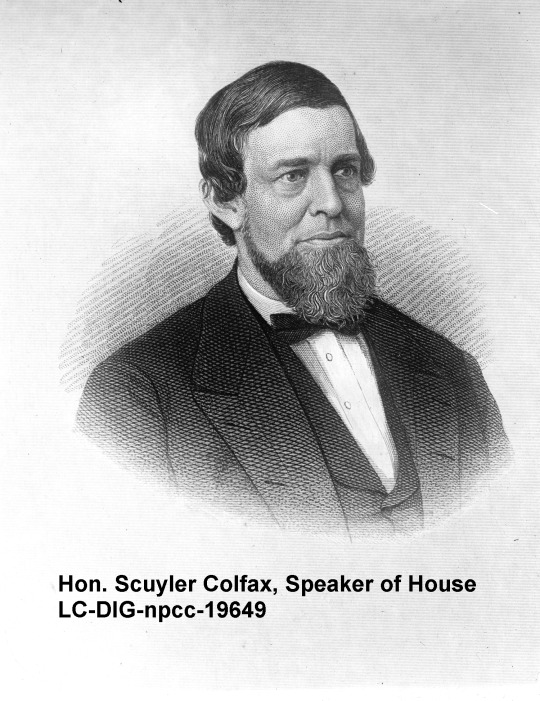

“The foothold created by prisoner-built roads in the Canal Zone enabled colonial officials, army engineers, and politicians in the United States to train their sights on a Pan-American Highway, which would run north-south from Alaska to Argentina. Convict road building in Panamá became part of the massively increased federal support for convict road building projects across states, territories, and colonies under US jurisdiction. Federal officials, meanwhile, pushed their modernizing agenda for prisons and roads at the convenings of international organizations like the Pan American Union (PAU) and the Pan American Prison Congress. The Pan-American Highway was shrouded in the rhetoric of hemispheric harmony, and PAU Director General L.S. Row described the “Good Roads Movement” as encapsulating “the very essence of true Pan-Americanism.”

E.W. James, chief of the inter-American regional office of the Public Roads Administration, promised the highway would open up great tracts of land and offer US motorists scenes of “exotic interest,” discovery, and adventure. Probably “no white man” has ever traveled between Central and South America overland, he wrote referring to the Darién Gap between Panamá and Columbia. He provided a list of voyages along portions of the highway, including that of Zone policeman 88, Harry A. Franck. At the 1915 Panama-Pacific World’s Fair in San Francisco, the US Office of Public Roads staged the most comprehensive road exhibit to date. By the end of World War II, the inter-American portion between the United States and Panamá included 1,557 miles of paved roadway, 930 miles of all-weather, 280 miles of dry-weather, and 567 miles of trails. “The last quarter century in the Western Hemisphere has been preeminently an era of road building,” James proudly concluded.

Forced transportation was central to the chattel mode of incarceration, along with degrading hard labor. Throughout the period of US canal construction, 1904–1914, police and prison officials routinely deported people from the Zone. Indeed, when he was appointed police chief, George Shanton saw it as his first order of business. Before he was even expressly granted expanded deportation powers, he gathered members of Teddy Roosevelt’s “Rough Riders” and other “American gunmen” to round up any “bad men” in the newly occupied territory.

“We went after them and some we found necessary to kill off but the great majority were gradually rounded up and placed in the stocks, later being put into bull-pens which we constructed,” he told the Boston Globe years later. “The next thing to do was to get them out of the country altogether,but we were in a position where we could not legally deport them. So we rounded up some old three masters […] and, bundling the birds all aboard, shot them off to the Islands thereabout.”

His nonchalance masked a more systematic process of targeted depopulation that combined Spanish-speaking Afro-Panamanians, French-speaking Martinicans, and English-speaking Jamaicans and Barbadians under the general category of “negro criminal,” who were then indiscriminately sent off to neighboring Caribbean islands. “With them out of the Zone,” Shanton wrote, “we were then in a position of refusing them entrance should they attempt to return.”

Canal Zone District Attorney William Jackson argued that the “great expense” the government had incurred by paying to transport some twenty thousand workers from Barbados and elsewhere in the West Indies “abundantly justified” expanded powers of deportation and judicial cost savings measures. The Canal Zone government paid the cost of deportation, he added, and rightly recouped the “enormous expense incident to jury trials.” As with other labor recruitment contracts, some officials worried they were skirting a line too near slavery. Responding to John Steven’s request to import more Chinese laborers, for instance, Secretary of War William Taft wrote, “peonage or coolieism, which shortly stated is slavery by debt, is as much in conflict with the Thirteenth Amendment of the Constitution as the usual form of slavery.” Others were less concerned. Despite apparent ambiguities in charting these degrees of unfreedom, they knew for certain that the Thirteenth Amendment’s convict clause provided that those convicted of a crime would become slaves of the state. Following a paradigm of patriarchal governance, Canal officials also assumed that other forms of dependent or coerced labor—of women, children, and colonial subjects—were part of the natural order of things. Evidently paying the passage of a small fraction of the total Canal Zone workforce had metaphorically, if not contractually, already indentured much wider segments of the population in the eyes of certain administrators.

...

The police and prison guards charged with implementing the forced labor program brought their own ideas about dependency, deviance, punishment, and work. Racialized labor control schemes had been vitally important to their jobs throughout the American empire. Zone policemen like Harry Franck and Robert Lamastus remarked that their fellow officers were mostly Southerners and almost all military men. Police Chief George Shanton, for instance, had served in the Rough Riders during the US wars in Puerto Rico and the Philippines. His successor had been a Confederate blockade runner, and the police chief after him was a former US Marshal in Indian Territory. When a police chase was on, wrote Harry Franck, everyone from the lieutenant down to the newest rookie would swarm out of the police station: “[T]he most apathetic of the force were girding up their loins with the adventurous fire of the old Moro-hunting days in their eyes, and all, some ahorse, more afoot, were dashing one by one out into the night and the jungle.” With this turn of phrase, Franck evoked the experience of colonial violence from fighting in the predominantly Muslim region of the Philippine archipelago to characterize the rush of tracking alleged outlaws in the Panamanian jungles as a kind of manly “adventure.”

Robert Lamastus, who was put in charge of working prisoners outside the penitentiary, exemplified many of these elements guards brought to the road gangs. With his family back in Kentucky, heavily indebted after the Civil War, he had gone fortune-seeking in the far reaches of the Northwest, joining the army in Alaska. He dreamed of striking it rich prospecting for gold or purchasing land to clear and cultivate. Yet his letters home made clear that he envisioned himself directing rather than performing hard physical labor; referring to farm work, for example, he exclaimed that there were “plenty of easier ways of making a living besides working like a slave for it.” Lamastus joined the police force in 1907 and was rapidly promoted. Within two years he was making $107.50 per month, five times what he earned when he first enlisted in the army, and the following year he received an additional $10 a month to serve as labor foreman over prisoners at Culebra. “We are building roads with them,” he wrote home, “I start work at 7 in the morning and I am through 5:30 in the evening.”

After successfully completing his road building assignments in the town of Empire, he was made Assistant Deputy Warden in charge of all outside work. “I was promoted on the 19th of Dec. my pay is $125 per mo.” he proudly wrote home. In addition to his salary, as Gold Roll employees, white police and prison officers like Robert Lamastus also received the full range of government benefits including paid housing, health care, and vacations. The racially segregated social and economic hierarchies he and his colleagues helped establish in the Canal Zone therefore ensured that white American men, as a group, would stand to gain the most from the incarceration and forced labor of Zone inhabitants deemed criminals.

The Canal Zone governors, wardens, police, and prison guards who implemented the prison labor program drew on techniques of labor extraction and domination that had characterized the American expansion under slavery, settler colonialism, and war-making. While they were not all members of the ex-Confederate diaspora who sought to spread white supremacy across the Caribbean to Brazil, or across the Pacific to Hawaii, Fiji, and Australia, most shared lived experiences of slavery and colonial violence. They also shared a vision of patriarchal mastery and racial hierarchy in which white men assumed themselves to be the head, performing mental and skilled labor, and racialized others to be the body, performing unskilled, physically demanding, menial labor. Their vision of white settler-colonial agricultural development depended on roads being built throughout the Zone and across Panamá. It also provided prison administrators and guards a unique avenue of upward social mobility. After a career commanding prison labor in the Canal Zone and directing the Panamanian island prison colony at Coiba, for example, Robert Lamastus went on to set up coffee plantations in Boquete, Chiriqui, that have remained in his family to this day.”

- Benjamin D. Weber, “The Strange Career of the Convict Clause: US Prison Imperialism in the Panamá Canal Zone,” International Labor and Working-Class History No. 96, Fall 2019, p. 88-90, 91-92.

Image at top is: “Road Making by Convicts” from Willis J. Abott, PANAMA And the Canal IN PICTURE AND PROSE. New York: Syndicate Publishing Company, 1913. p. 352.

#panama canal#canal zone#thirteenth amendment#convict clause#convict labour#american prison system#american empire#u.s. imperialism#penal labour#slavery by another name#settler colonialism#road building#road work#prison camp#good roads movement#bad boys make good roads#academic quote#academic research#history of crime and punishment#united states history#prison guards#racism in america#shoveling out the unwanted

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

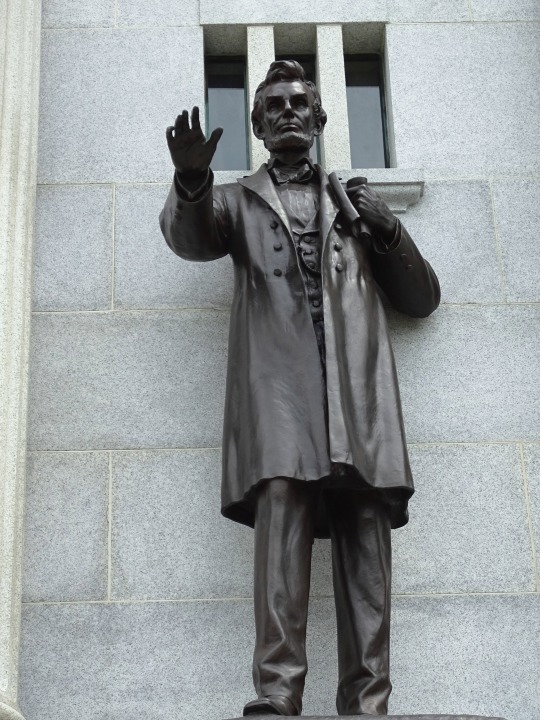

President Abraham Lincoln signed the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution (abolished slavery and involuntary servitude) on February 1, 1865.

National Freedom Day

Honoring the signing of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, which abolished slavery in America, National Freedom Day is an annual United States observance to celebrate the nation’s freedom and recognize the efforts of those who fight to protect it.

History of National Freedom Day

National Freedom Day was established by a Civil Rights leader, businessman, and former slave named Major Richard Robert Wright Sr. Wright, who was born into slavery in 1855, saw the need for a day to commemorate when the 13th Amendment was signed, and to identify the ongoing struggle for civil rights. He believed that the 13th Amendment was an important milestone in establishing freedom and equality for all Americans, and he wanted to ensure that it would never be forgotten.

In 1941, Wright began lobbying for the establishment of National Freedom Day and, in 1948, a year after his passing, it was officially recognized by the United States government. It is celebrated every year on February 1st, the same day the 13th Amendment was signed into law in 1865.

National Freedom Day serves as a reminder of the long and difficult journey towards equality for all American citizens. It is a day to remember the struggle of those who fought for their rights, and to recognize the continuing fight for civil rights.

National Freedom Day Timeline

February 1, 1865 13th Amendment Abolishes Slavery

The 13th Amendment to the Constitution is signed into law, officially abolishing slavery in the United States. This marks a significant step towards freedom and equality for all Americans and marks the end of a long and difficult journey.

June 30, 1948 National Freedom Day Established

This day is officially recognized by the United States government as a day of observance, signed into law by President Harry S. Truman.

1960s Civil Rights Movement Gathers Steam

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s sees a renewed push for equality and freedom for all Americans. It is a time of great progress and change, and serves as a reminder that the fight for civil rights is far from over.

November 4, 2008 Barack Obama Elected President

The first African American president of the United States, is elected, symbolizing progress and change in the ongoing fight for civil rights.

January 20, 2021 First African-American and Asian-American woman vice president

Kamala Harris becomes the first African-American and Asian-American woman to hold the office of Vice President, a symbol of progress and change.

How to Celebrate National Freedom Day

National Freedom Day is celebrated annually on February 1st by individuals, organizations, and communities across the United States. Many states observe National Freedom Day with a special ceremony, parade, or other event, along with speeches, performances and educational programs.

Many people choose to mark the day with their own private ceremonies and celebrations, such as visiting historical sites, lighting candles, or making donations to organizations that promote freedom and civil rights. Here’s a few ideas for how to observe the day:

Attend a National Freedom Day Event

Many communities hold events or ceremonies to commemorate National Freedom Day. These events may include speeches, performances, or educational programs and can be arranged by local schools, churches, or civil rights groups. Attending one of these events is a great way to honor the legacy of those who strove for freedom, and to learn more about the history of the 13th amendment.

Learn About the History of Slavery

National Freedom Day is an opportunity to learn about the history of the Civil Rights Movement. Read books, watch documentaries, or visit museums to deepen your understanding of this important part of American history. By learning about the past, we can better understand and appreciate the progress that has been made and the work that still needs to be done.

Participate in a Community Service Project

National Freedom Day is a day to give back to your community and promote equality and freedom for all. Participate in a volunteer or community service project to make a positive impact in your community. This could include volunteering at a local school, community center, or non-profit organization. It could also include participating in a community clean-up or fundraising event.

Have a Discussion About Equality

Use National Freedom Day as a chance to have a family discussion about freedom and equality. A great way to raise awareness and promote understanding and empathy within your own family is to talk about the Civil Rights Movement with them, the history of slavery, and the current state of civil rights in America. Encourage family members to share their thoughts and feelings about these issues.

Source

#Emancipation Statue by Thomas Ball#Boston#Massachusetts#San Diego#California#Breaking the Chains by Melvin Edwards#Washington DC#USA#Daniel Chester French#Gettysburg#Abraham Lincoln#Thirteenth Amendment#1 February 1865#anniversary#US history#original photography#tourist attraction#Mount Rushmore National Memorial#Gutzon Borglum#National Freedom Day#NationalFreedomDay#South Carolina#Columbia#African-American History Monument by Ed Dwight

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“in my indulgence era” you’re doing an advertisement for walmart, a company that supports and profits from slave labor under the 13th amendment, which prohibits slavery except as punishment for a crime, which allowed the overwhelming enslavement of black and brown bodies that began during the colonial era to continue and set the stage for the current paradox of majority black and brown bodies incarcerated in us prisons. when and where and how is that considered indulgence. what are you fucking indulging in. legalized enslavement in the 21st century?

#blue rambles#walmart#consumerism#capitalism#united states#13th amendment#thirteenth amendment#advertisement#the us prison system is legalized slavery#are you supporting it?#black history is american history#black history#begging y’all to READ about this and stop shopping @ walmart#target whole foods and mcdonald’s too#so many more#so. many. more.#target#whole foods#aldi#us prison system#us prisons

1 note

·

View note

Text

Slavery implies involuntary servitude,-a state of bondage; the ownership of mankind as a chattel, or, at least, the control of the labor and services of one man for the benefit of another, and the absence of a legal right to the disposal of his own person, property, and services. This amendment was said in the Slaughter-House Cases, 16 Wall. 36, to have been intended primarily to abolish slavery, as it had been previously known in this country, and that it equally forbade Mexican peonage or the Chinese coolie trade, when they amounted to slavery or involuntary servitude

Henry Billings Brown, Plessy v. Ferguson

#thirteenth amendment#human trafficking#immigrant labor#child labor#henry billings brown#brown#1896#brown 1896#plessy v. ferguson#plessy v ferguson

0 notes

Text

The Uses of History, 10 – USA Meltdown, 1

The Uses of History, 10 – USA Meltdown, 1

History is a dance with the past, with a phantom or ghost – sometimes well-defined, sometimes mere outline, always mysterious.

VJM, 2022

The infant United States of America emerged from its successful Revolution in 1783 far from unified. The Treaty of Paris brought peace with Great Britain and an enormous addition of territory between the Appalachians and the Mississippi River. But it did not…

View On WordPress

#Abigail Adams#American Constitution#American Revolution#Articles of Confederation#Equal RIghts#Quakers#Slavery#Thirteenth Amendment#Thomas Jefferson#Unfinished Revolution

0 notes

Photo

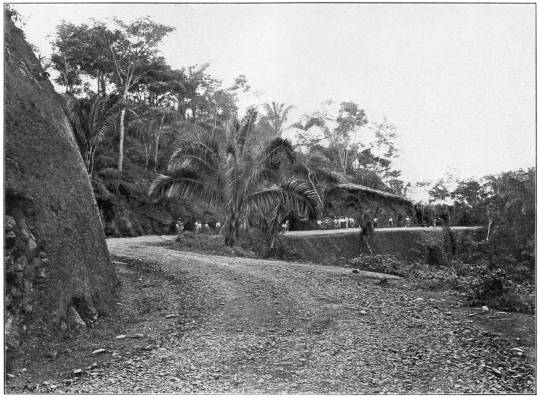

The congressional vote on the Thirteenth Amendment was scheduled for January 31, 1865. Speaker Colfax asked that his own name be read so that he could be recorded on this historic issue and he announced the results 119 yea, 56 nay. Eight members deliberately did not vote, making it easier to achieve the two-thirds mark of "those present and voting."

The members on the floor huzzaed in chorus with the galleries The ladies in the House assemblage waved their handkerchiefs. Again and again the applause was repeated.

0 notes

Text

smthin smthin nu!who's journey of the doctor and earth as home

nine's continued discomfort with "the domestic"

ten staying with the tylers' over christmas and then resisting the same with donna after losing rose/that life, and that continuing throughout knowing martha, then, later still getting to know wilf and leaving donna at her home before cutting ties with everyone from that life

eleven for a brief time living with the ponds, but with one step inside the tardis the whole time, and briefly going to clara's one christmas

twelve barely getting involved in clara's home life at all, but then with bill going back to the idea of family in a sort of tentative cautious kind of way? -- taking a picture of her mum for her, helping her move into her (briefly) held accommodation, and generally being read as bill's grandfather/family

thirteen meeting yaz' family and being asked if they're dating, and travelling with multiple generations of a family for some time (echoing rose and jackie and mickey, donna and wilf, the ponds + rory's dad), and possibly having some very conflicting feelings about leaving especially yaz behind

fourteen staying with the noble family

#i think... it is interesting... Telling even perhaps... that martha never had this.... telling in the sense that martha deserves better#ten DID of course meet martha's family but their whole memory of everything is: horror fear torture bad horror bad#not that martha now would want a domestic involvement with the doctor but oof... oh she hit brick walls every time didnt she#wherever martha is fourteen and/or fifteen should make some kind of amends#not that the events of the doctor's daughter was ten's fault but man#martha never caught a break did she#doctor who#dw#doctor who spoilers#dw spoilers#the doctor#the tenth doctor#the eleventh doctor#the twelfth doctor#the thirteenth doctor#the fourteenth doctor#no analysis of nu!who is complete without going *AND MARTHA'S STORY IN ALL THIS!*

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Go and tell them

Last week, I read up a bit about the American celebration of Juneteenth (19 June), a federal holiday which Wikipedia records is ‘commemorating the emancipation of enslaved African Americans.’ In fact it is so much more than that.

One such important takeaway for me was the fact that it isn’t a celebration of the actual proclamation of the freedom of all humans in the up-until-then Divided States…

View On WordPress

#Black Lives Matter#Book bans#Democrats#Gerrymandering#Juneteenth#Kevin McCarthy#Mass shootings#Republicans#Second Amendment#Slaves#South African Constitution#Thirteenth Amendment of teh Constitution of teh United States#Voting Rights Act#Women&039;s Rights

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Thirteenth Amendment Framework for Combating Racial Profiling

Excerpted From: William M. Carter, Jr., A Thirteenth Amendment Framework for Combating Racial Profiling, 39 Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review 17 (Winter, 2004) (387 Footnotes) (Full Document)

Racial profiling, or the use of race as an ex ante basis for criminal suspicion, has been the subject of much scrutiny and debate. Traditionally, those who support the use of race as an element of criminal profiles have argued that the practice is merely a reflection of racially disparate crime rates. If African Americans, for example, commit more crime, it only makes sense to include race as an element of profiles used to predict criminal conduct. Furthermore, many would argue that African Americans and other minorities are simply too sensitive and would characterize opposition to racial profiling as "political correctness." Since crime rates are racially disproportionate, ignoring such evidence in the name of cultural sensitivity costs us all, especially racial minorities whose communities are disproportionately affected by crime.

Opponents of the practice respond with studies showing that rates of drug use (drug interdiction being the context in which racial profiling is most commonly employed) are not in fact racially disproportionate, or at least not so disproportionate as to justify the massive racial disparities regarding whom law enforcement officers single out for suspicion. Most opponents of racial profiling would further argue that even if there is some racial disparity in crime rates generally, the social costs of racial profiling outweigh the modest or arguable efficiency gains of the practice. Litigants and scholars opposing racial profiling have therefore focused on the Fourth Amendment's prohibition of unreasonable searches and seizures and the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause in seeking to attack the practice.

The historical context of race-based criminal suspicion is largely lost in the debates and jurisprudence regarding racial profiling. This Article contends that the Thirteenth Amendment, in contrast to the equal protection paradigm that is currently the focus of racial profiling jurisprudence and scholarship, provides a stronger constitutional basis for combating this lingering vestige of slavery. Rather than focusing on arguments about efficiency or abstract "equal treatment" under the Equal Protection Clause, a Thirteenth Amendment framework for examining racial profiling forces us to recognize and confront the continuing effects of slavery and the social and legal structures that supported it. Accordingly, this Article seeks to redirect the debate over racial profiling toward a frank consideration of the historical permanence of the assumption of innate black criminality; the roots and purpose of that stereotype in the system of chattel slavery and the subjugation of African Americans after the end of slavery; and its continuing effects on African Americans today.

The Supreme Court has long recognized that the Thirteenth Amendment was intended not only to destroy human enslavement as an economic institution, but also to eliminate the lingering effects of the slave system. Shortly after passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, the Court held that the Thirteenth Amendment empowered Congress not only to end chattel slavery but also to "pass all laws necessary and proper for abolishing all badges and incidents of slavery." In Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., the Court revitalized the Thirteenth Amendment, which had lain largely dormant for over a century after its passage, by holding that private white persons' refusal to sell property to African Americans constituted a badge or incident of slavery. This Article, while recognizing the need for some discernable limits to the badges and incidents of slavery theory of the Thirteenth Amendment, does not attempt to provide a comprehensive theory of those limits in all circumstances. Rather, I seek here only to sketch the framework of such limits in the context of racial profiling.

Racial profiling is best understood as a current manifestation of the historical stigma of blackness as an indicator of criminal tendencies. This stereotype arose out of, and was essential to, slavery in the United States. The demonizing of African Americans as the dangerous, uncontrollable "other" made it easier to reconcile the American ideal of liberty for all persons with the reality of enslavement. The myth of innate black criminality served both to dehumanize African Americans during slavery and to justify the brutal means of social control needed to maintain white dominance after the end of slavery.

My purpose here is not to equate racial profiling with slavery. Doing so would minimize the suffering of the millions of Africans enslaved in this country. I do not argue that the injury caused by racial profiling is as severe as slavery, nor that African Americans today in any way experience the nearly unimaginable degradation of slavery. Rather, this Article contends that the widespread stigmatization of African Americans as predisposed toward criminality is a lingering vestige of the slave system and is therefore outlawed by the Thirteenth Amendment.

It is clear that persons who are not African American can suffer a "simple" Thirteenth Amendment injury; that is, any person of any race can be enslaved or compelled to labor for another. $%^19 This Article focuses on racial profiling of African Americans, however, because (1) they are the original subjects of the Thirteenth Amendment and (2) they are the most likely to suffer slavery's badges and incidents. $%^20 While other ethnic minorities are also saddled with popular perceptions of group propensity for crime, those assumptions tend to operate differently, and perhaps more narrowly, than the widespread stereotype of black criminality.

Part II of this Article discusses the phenomenon of racial profiling, the damage racial profiling inflicts, and the traditional bases for opposing the practice.

Part III examines the inadequacy of current constitutional jurisprudence regarding racial profiling.

In Part IV, I examine the history and purposes of the Thirteenth Amendment as well as major Thirteenth Amendment jurisprudence. I also examine the historical continuity of African Americans' stigmatization as congenital criminals and contend that race-based criminal suspicion is indeed a "badge or incident" of slavery in violation of the Thirteenth Amendment.

Part V discusses Congressional and judicial power under the Amendment and rebuts arguments that slavery's lingering effects may only be prohibited by Congress under the Thirteenth Amendment's enforcement clause and may not be judicially addressed under the Amendment's self-executing core.

Part VI briefly reviews some benefits of, and concerns about, the "badges and incidents of slavery" theory of racial profiling. This Article concludes that racial profiling, even in the absence of Congressional legislation, is a violation of the Thirteenth Amendment, and calls on the judiciary to construe the Amendment to fulfill its promise to rid the freedmen and their descendants of slavery's legacy.

[. . .]

Racial profiling remains a significant problem for racial minorities in general and African Americans in particular. Courts have construed the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments in ways that preclude any effective remedy. Congress has also proved unwilling to adopt legislation addressing the problem.

The Thirteenth Amendment, based upon its legislative history, historical context, and interpretation in Jones, remains a viable and powerful remedy for racial profiling. The Thirteenth Amendment's promise was to eliminate all of slavery's lingering vestiges, not just to end the institution of chattel slavery. A Thirteenth Amendment approach to racial profiling takes into account the legacy of the entwinement of race and criminal suspicion and the fact that the officially enforced presumption of black criminality arose out of the slave system and was integral to maintaining it. A Thirteenth Amendment analysis also forces us to confront the purposes served by the stereotype of black criminality historically and recognize that those same purposes are served today, albeit in a "gentler" form. Because the effects of this stigma persist today, it is properly considered a modern-day badge or incident of slavery. Courts should recognize and fully enforce the Amendment's radical purposes by providing a direct Thirteenth Amendment cause of action for victims of racial profiling. The alternative--ignoring this badge of slavery--means "the Thirteenth Amendment made a promise the Nation cannot keep."

Assistant Professor, Case Western Reserve University School of Law.

#A Thirteenth Amendment Framework for Combating Racial Profiling#Racial Profiling in america#Black Lives Matter#Systemic Racism#overeach of police#militarization of police in america#police violence directed at Black People#13th amendment

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#music lovers#music promotion#human rights#black power#black rights#anti racism#mass incarceration#modern slavery#"Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude#except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted#shall exist within the United States#or any place subject to their jurisdiction.#-thirteenth amendment#Youtube

0 notes

Photo

“After the US military occupied the Isthmus of Panamá and the HayBunau-Varilla Treaty was signed, President Theodore Roosevelt issued a series of executive orders to establish US law in the Canal Zone. The 1904 treaty provided the US government with “all rights, power, and authority which it would possess and exercise if it was the sovereign of the territory,” and Roosevelt’s orders created an outline for the criminal legal system. He gave the governor and the Isthmian Canal Commission (ICC) sweeping exclusion and deportation power, and initially chose not to extend the right to jury trial. The Thirteenth Amendment’s “convict clause” was central among the constitutional guarantees that were selectively extended: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall exist except as punishment for crime,” the order proclaimed. As Canal Zone District Attorney William Jackson described it, the sources of law included a mix of executive orders, congressional acts, Columbian civil law, local ordinances, criminal codes of procedure, and military doctrine, all of which were designed to ensure labor productivity.

....

The ICC convened a “Special Committee on the Employment of Prisoners” in the Panamá Canal Zone in 1908. Proposing that convicts be forced to build roads, their stated aims were threefold: to reimburse the Government for the expense of maintaining its penal system, to open the fertile valleys of the Canal Zone to development, and to improve the condition of the prisoner. The convict road-building program began in March of 1908, when Governor Joseph Blackburn authorized the transport and housing of prisoners outside the Culebra penitentiary. As a Kentucky plantation owner and former Confederate officer in charge of an independent command in Mississippi, he was familiar with regimes of forced labor as well as military-style work camps. On his order, Canal Zone police established a portable camp at Brazos Brook and moved half of the penitentiary population there to be near the work at all times.

Clearing, cutting, grading, leveling, draining, filling—each stage of the road-building process presented its own arduous challenges. Work must have been especially grueling that first summer, as those who were imprisoned were forced to grade a sixty-foot slope leading to a bridge they would have to build over the Miraflores dump. But perhaps even that gang, averaging one hundred prisoners daily, did not envy their fellow prisoners who were sent to fill swamps at West Culebra in May, or those who spent over twenty-five thousand total hours filling the Lirio swamp in August and September. By fall, work had begun on the Empire-Paraíso section of road and seventy prisoners were transferred to a new convict labor camp on the side of Gold Hill. They had already put in over 140,000 total hours on the highway between the towns of Empire and Bas Obispo. When Chief Engineer George Goethals announced the opening of the highway to Empire in his “Notes on Progress” in September of 1910, it had taken over a year for prisoners to build the 18,392-foot long, 18-foot wide stretch of roadway. They excavated some 17,457 cubic yards of material for the subgrade, laid 2,563 cubic yards of gravel, and another 2,860 cubic yards of stone in the process.

Reimbursing the government for the expense of maintaining the penal system was one of the three central aims of the ICC Special Committee on the Employment of Prisoners. Monthly police reports made the financial record of prisoners’ labor publicly available. The system of accounting for the value of prison labor used a fixed hourly wage rate and then subtracted the cost of their subsistence, clothing, and guarding. At the program’s inception, the chief of police reported that the division of municipal engineering credited the department of civil engineering eighty cents per day for each convict employed on the roads. He was proud to report that the experiment was proving profitable: “The Department of Civil Administration finds that the revenue from its prisoners is greater than the expense of keeping them.”

Yet that was not the total cost of maintaining the penal system; the payroll for 150 members of the police force was still listed at ten times the value of road work performed by about the same number of prisoners. One year later, the monthly value of prisoner roadwork was reported as $1,821.55, while the cost of subsistence was $857.75, clothing was another $378.80, and guard payroll was an additional $1,473.76.31 By 1914, the value of work surpassed the cost of “prisoner maintenance.” The costs involved in road building, meanwhile, were reported in local newspapers in a such a way as to reinforce the idea that their work was already a naturally unpaid, and presumably unobjectionable, part of the equation. It was estimated, for example, that the Empire-Gamboa Road would cost $17,952.98, “exclusive of convict labor.”

Once incarcerated and designated for road work, Canal Zone prisoners were made to clear the ground, build portable camps, haul water, prepare food, and clean. The force “does its own cooking and takes care of the sanitation of the camp,” claimed one monthly police report. By making them responsible for their own social reproduction, such as it was, colonial officials and prison guards sought to turn prisoners into pure surplus. In 1913, a photographer from the Keystone View Company captured one of these “convict corrals” in the background of a photograph of a “Thatched Roof Native Home.” Of course, the caption read, “this corral is a temporary structure because these convicts are transported from point to point, according to where their labor is needed.” Intrigued, the photographer captured the camp itself. “We have a closer view of the corral partially seen in view 21740,” they wrote. “The corral is the temporary quarters for the prison convicts, who are here employed in building a macadam road.” The image [SHOWN BELOW] depicts the barbed-wire enclosure and an officer “brandishing a revolver,” described as “necessary assistants in such camps,” as well as the prisoners’ mess table shown in the foreground.

The stereograph’s caption explained how “the roads are being built by the United States Government and the convicts here located are prisoners sentenced for misdemeanors done in the Canal Zone.” Perhaps in an attempt to portray the prison system as racially unbiased, the Keystone View Company’s writer added, “Naturally these prisoners are of all races and colors.” But in fact, the prison population and road gangs they were looking at were disproportionately black. “In the Canal Zone is to be found, doubtless, the only place where the National Government uses convicts for road construction,” they noted, while in some southern states “convict labor is the usual one employed in building roads,” the practice had not yet been taken up in the nation’s federal penitentiaries. Stereographs like these, together with photographs in news reports and exhibitions like the 1915 World’s Fair, were instrumental in constructing the visual representation of the Canal Zone’s prison labor program to the US public in ways that obscured the racial violence of Uncle Sam’s chain gangs.

Another goal of the Special Committee on the Employment of Prisoners was to open the fertile valleys to cultivation and development, by which they meant to white settlement. When Governor Blackburn first authorized the prison road gangs, ICC officials explained it this way: “the intention is to locate these roads away from the railroad so as to develop the agricultural recourses of the country to as great an extent as possible.” The roads were designed to facilitate settlement and plantation-style agriculture both within the Zone and in the neighboring Republic of Panamá. Zone administrators pressured their government counterparts in Panamá, urging them also to employ convicts to build connector roads outside the Zone. As civil engineer J.G. Holcombe told The Daily Star and Herald, he intended to get to work at building roads throughout Panamá and would use prison laborers wherever possible so they would cost a minimum outlay. The Star and Herald reported that a highway would be built from the town of Empire in the Canal Zone through to Chorrera, in the Republic of Panamá:

“From Empire to Arraijan the trail traverses one of the best agricultural sections of the Zone and a large amount of fruit and produce is brought over it by pack horse and marketed in Empire.”

It was nine more miles, however, from the edge of the Zone boundary to the “native village” of Chorrera, a town of about thirty-five hundred people with “many farms of considerable extent” growing corn and other produce and raising cattle. The Government of Panamá has given assurance, a reporter assured readers, that it will continue the highway built to the Zone line into Chorrera, “thereby making the entire section of country accessible to Empire.”

The Canal Zone prison road-building scheme was situated squarely in an ongoing debate over settlement versus depopulation. Those who favored settler colonialism in the Zone, advocated roads be built in order to connect agricultural plantations to markets. As the Canal Zone Governor George Goethals told it a few years later, the group in favor of establishing a white settler colony “asserted that Americans should be permitted to take up land, provision being made for homesteading it as an inducement … the assumption being that they would have farms or plantations worked by West Indian negroes; the general idea amounted to opening up the land to ‘gentlemen farmers.’”

Goethals himself, however, opposed settlement in favor of depopulation after work on the canal was complete in 1914. “I did not care to see a population of Panamanian or West Indian negroes occupying the land, for these are nonproductive, thriftless, and indolent,” he wrote. According to his racial nightmare, they would not only act as unproductive squatters, but drain government resources by congregating in small settlements and costing the government money for sanitation and police. As his theory about the increased cost of policing suggests, he speculatively criminalized those he lumped into the category “negro” and deemed as an unwanted surplus population once their labor was no longer needed on the canal. The irony was that throughout the canal construction period, only black Silver Roll employees paid income tax, which supported such public services, while white Gold Roll employees paid no income tax and received a range of free and subsidized government benefits.

Through these type of discussions over depopulation, criminality, and prison labor, Canal officials actively inverted the meaning of who was generating value and who was supposedly a burden on the government. In a declassified record from the ICC’s executive office at the end of canal construction, officials noted that in addition to those they had deported and those “removed in the course of depopulation,” the ICC planned to begin transporting people who were now out of work “as a police measure.” Their justification for mass deportations revealed the logic at work in speculatively criminalizing unemployment and poverty:

“[A]ny increase in crime always occurs where conditions cause a large number of men to be without employment,”

wrote Police Chief Mitchell, expressing what seemed like a timeless, race-neutral, truism.

Yet he and Mr. Copeland knew exactly what group they were targeting: “Nearly all police cases in Panama for wounding, sneak thieving, robbery and fraud,” he speculated, “are those of Jamaicans who are out of work on account of termination of canal work.” They were also clearly ambivalent about those they deemed as surplus, whose lives they evidently did not consider very valuable. While Mitchell proposed removing all “unemployed aliens” from the Isthmus if the US government “had to take care of them,” for example, he added that they actually might need all available labor for defense measures, adding that “such labor could be forced.”

- Benjamin D. Weber, “The Strange Career of the Convict Clause: US Prison Imperialism in the Panamá Canal Zone,” International Labor and Working-Class History No. 96, Fall 2019, p. 83-88.

Image at top is: “CONVICTS BUILDING A COMMISSION ROAD: The excellence of these roads should be an object lesson to Central America.” from Willis J. Abott, PANAMA And the Canal IN PICTURE AND PROSE. New York: Syndicate Publishing Company, 1913. p. 348.

#panama canal#canal zone#thirteenth amendment#convict clause#convict labour#american prison system#u.s. imperialism#american empire#penal labour#forced labour#slavery by another name#settler colonialism#road building#road work#prison camp#academic research#research quote#academic quote#isthmian canal commission#history of crime and punishment#united states history

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

President Abraham Lincoln signed the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution (abolished slavery and involuntary servitude) on February 1, 1865.

National Freedom Day

Honoring the signing of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, which abolished slavery in America, National Freedom Day is an annual United States observance to celebrate the nation’s freedom and recognize the efforts of those who fight to protect it.

History of National Freedom Day

National Freedom Day was established by a Civil Rights leader, businessman, and former slave named Major Richard Robert Wright Sr. Wright, who was born into slavery in 1855, saw the need for a day to commemorate when the 13th Amendment was signed, and to identify the ongoing struggle for civil rights. He believed that the 13th Amendment was an important milestone in establishing freedom and equality for all Americans, and he wanted to ensure that it would never be forgotten.

In 1941, Wright began lobbying for the establishment of National Freedom Day and, in 1948, a year after his passing, it was officially recognized by the United States government. It is celebrated every year on February 1st, the same day the 13th Amendment was signed into law in 1865.

National Freedom Day serves as a reminder of the long and difficult journey towards equality for all American citizens. It is a day to remember the struggle of those who fought for their rights, and to recognize the continuing fight for civil rights.

National Freedom Day Timeline

February 1, 1865 13th Amendment Abolishes Slavery

The 13th Amendment to the Constitution is signed into law, officially abolishing slavery in the United States. This marks a significant step towards freedom and equality for all Americans and marks the end of a long and difficult journey.

June 30, 1948 National Freedom Day Established

This day is officially recognized by the United States government as a day of observance, signed into law by President Harry S. Truman.

1960s Civil Rights Movement Gathers Steam

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s sees a renewed push for equality and freedom for all Americans. It is a time of great progress and change, and serves as a reminder that the fight for civil rights is far from over.

November 4, 2008 Barack Obama Elected President

The first African American president of the United States, is elected, symbolizing progress and change in the ongoing fight for civil rights.

January 20, 2021 First African-American and Asian-American woman vice president

Kamala Harris becomes the first African-American and Asian-American woman to hold the office of Vice President, a symbol of progress and change.

How to Celebrate National Freedom Day

National Freedom Day is celebrated annually on February 1st by individuals, organizations, and communities across the United States. Many states observe National Freedom Day with a special ceremony, parade, or other event, along with speeches, performances and educational programs.

Many people choose to mark the day with their own private ceremonies and celebrations, such as visiting historical sites, lighting candles, or making donations to organizations that promote freedom and civil rights. Here’s a few ideas for how to observe the day:

Attend a National Freedom Day Event

Many communities hold events or ceremonies to commemorate National Freedom Day. These events may include speeches, performances, or educational programs and can be arranged by local schools, churches, or civil rights groups. Attending one of these events is a great way to honor the legacy of those who strove for freedom, and to learn more about the history of the 13th amendment.

Learn About the History of Slavery

National Freedom Day is an opportunity to learn about the history of the Civil Rights Movement. Read books, watch documentaries, or visit museums to deepen your understanding of this important part of American history. By learning about the past, we can better understand and appreciate the progress that has been made and the work that still needs to be done.

Participate in a Community Service Project

National Freedom Day is a day to give back to your community and promote equality and freedom for all. Participate in a volunteer or community service project to make a positive impact in your community. This could include volunteering at a local school, community center, or non-profit organization. It could also include participating in a community clean-up or fundraising event.

Have a Discussion About Equality

Use National Freedom Day as a chance to have a family discussion about freedom and equality. A great way to raise awareness and promote understanding and empathy within your own family is to talk about the Civil Rights Movement with them, the history of slavery, and the current state of civil rights in America. Encourage family members to share their thoughts and feelings about these issues.

Source

#Emancipation Statue by Thomas Ball#Boston#Massachusetts#San Diego#California#Breaking the Chains by Melvin Edwards#Washington DC#USA#Daniel Chester French#Gettysburg#Abraham Lincoln#Thirteenth Amendment#1 February 1865#anniversary#US history#original photography#tourist attraction#Mount Rushmore National Memorial#Gutzon Borglum#National Freedom Day#NationalFreedomDay#South Carolina#Columbia#African-American History Monument by Ed Dwight

1 note

·

View note

Text

conservative think tanks will be named something like "the american educational initiative," and you read their policy proposals and it's like "let's repeal the thirteenth amendment and send slavery back to the states." meanwhile liberal think tanks will be named something like "the foundation for the redemption of america's soul," and their policy proposals are "a 5% increase in capital gains tax over the next ten years, but you don't have to pay it if you submit a note from your doctor saying it makes you sad."

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

I think one of Jude's majorly overlooked character traits is how funny he is. I still lose my mind everytime I read that one scene where Harold was interviewing Jude for his research assistant position and he mentions how, except for a few of them, the majority of the amendments in the constitution are the "dross" of politics past. Dross has a couple of meanings, the one Harold meant was "remnants" but another meaning is "worthless" and Jude is so quick to ask him "You think the thirteenth admendment is worthless 🤨?"

For non-Americans the thirteenth amendment is the one that abolished slavery lmfao get that white man Jude

#you think abolishing slavery is useless? smh harold#harold was so done w him in that scene lmfaooooo#thats NOT what i meant JUDE#but no fr jude can be so funny sometimes#a little life#jude st francis#a little life play#een klein leven#a little life book#harold stein

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

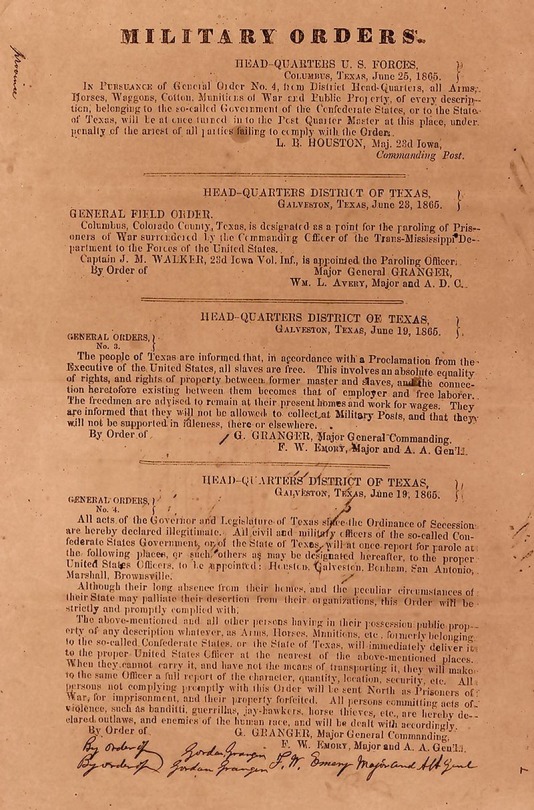

Today in 1865, Union forces occupying Texas issue General Order No 3, officially informing all slaves in the former Confederate state that they are henceforth free in accordance with the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863. The occasion would later be celebrated as Juneteenth, Freedom Day.

The general order was issued by Union General Gordon Granger on June 19, 1865, upon arriving at Galveston, Texas, at the end of the American Civil War and two and a half years after the original issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation.

A common misconception holds that the Emancipation Proclamation freed all slaves in the United States, or that the General Order No. 3 on June 19, 1865, marked the end of slavery in the United States. In fact, the Thirteenth Amendment, ratified and proclaimed in December 1865, was the article that made slavery illegal in the United States nationwide, not the Emancipation Proclamation.

General Order No. 3 states:

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.” (source)

While the order was critical to expanding freedom to enslaved people, the racist language used in the last sentences foreshadowed that the fight for equal rights would continue.

#juneteenth#black history#blacklivesmatter#june 19#general order 3#emancipation day#slavery#emancipation#general order number 3#otd#otdih

206 notes

·

View notes