#urushi nuri

Text

I got a Pilot Maki-e Seirei Nuri, displaying traditional Japanese art of dozens of layers of urushi lacquer meticulously applied and hand painted maki-e, in this case to replicate the pattern of dragonfly wings.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Red kara-nuri flattop. Kara-nuri is one of tsugaru-nuri techniques, developed in Aomori prefecture. They were shown to the world outside Japan on Vienna World Exhibition in 1873 as “lacquerware from Tsugaru” hence tsugaru-nuri. Pen takes Bock 6 nib and us available. . —— Most pens I show here are for sale. Contact me through direct message here or email: [email protected]. I do not have a webshop or a big stock. Some available pens I show on my website, usually after a week or two from presenting them here - link in bio. —— . #japaneselacquer #urushilacquer #japanart #蒔絵 #漆 #fountainpen #calligraphy #urushi #nakaya #danitrio #namiki #urushifountainpen #japanlacquer #tamenuri #tamenuristudio #vulpen #styloplume #万年筆 #estilográfica #handmade #penmaking #handwriting #pencollector #penmaker #penshow #penforsale #pensforsale #tsugarunuri #tsugaru #karanuri (at Warsaw, Poland) https://www.instagram.com/p/Ce9g_KRDEvW/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#japaneselacquer#urushilacquer#japanart#蒔絵#漆#fountainpen#calligraphy#urushi#nakaya#danitrio#namiki#urushifountainpen#japanlacquer#tamenuri#tamenuristudio#vulpen#styloplume#万年筆#estilográfica#handmade#penmaking#handwriting#pencollector#penmaker#penshow#penforsale#pensforsale#tsugarunuri#tsugaru#karanuri

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This is a Yotsubishi fountain pen with a Kawari-nuri sakura (cherry) bark pattern c. 1955-1959. The Kawari-nuri technique used on this pen begin with the cap, barrel and nib section are undercoated with a contrasting urushi and then overcoated with the desired surface color urushi. This outer surface is worked likely by sanding to reveal the pattern shown, a free pattern to simulate sakura (cherry) bark. It has a squeeze filler, similar to a Parker 51 aerometric in operation. #fountainpen #yotsubishi #urushi #kawarinuri #makie #artpen #pencollecting #cherrybark #sakura https://www.instagram.com/p/Ce7BfeRvrcd/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

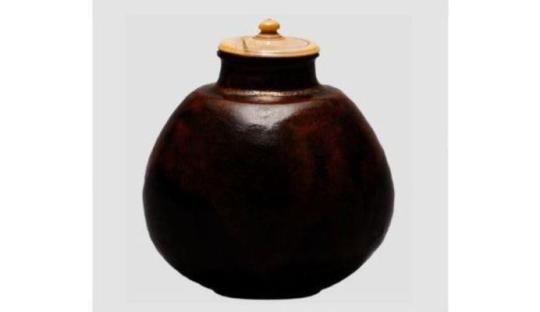

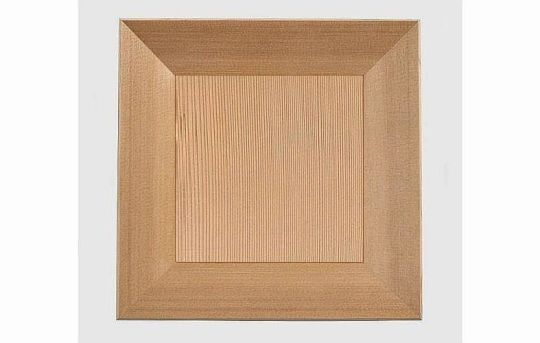

Nampō Roku, Book 7 (81): Jōō’s Matsu-no-ki-bon [松ノ木盆].

81) Concerning Jōō’s Matsu-no-ki-bon, [this tray] was suitable for use with the Tsuji-dō chaire¹.

[It] is of a large size².

Rikyū also, on a certain occasion when he was going to open some tea that had been received〚from His Highness,〛used a new Matsu-no-ki-bon that he had [just had] made [for the occasion]³.

[This new tray] was smaller⁴. It was also unpainted⁵.

_________________________

◎ As Tanaka Senshō notes in his commentary, it is important for the reader to understand that there were actually two Matsu-no-ki-bon [松ノ木盆] -- a large one, and a small one (these are shown below). And though the text is short and seems to be clear, the difference between what is said here and the historical record is a little problematic.

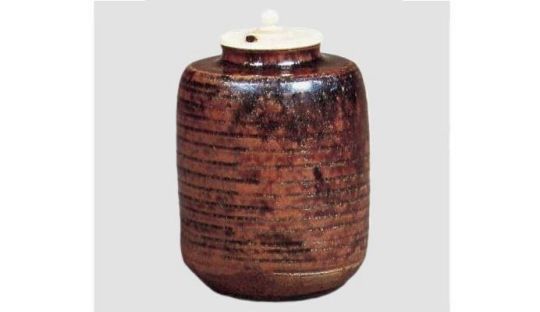

The large Matsu-no-ki-bon, which was made by Jōō, measures 8-sun 2-bu square. It was rubbed* (not painted) with honey-colored Shunkei [春慶塗] lacquer. The smaller Matsu-no-ki-bon was made by Rikyū. It measures 6-sun 2-bu square, and was painted (as Tanaka Senshō confirms) with tame-nuri [溜め塗]† (though the bottom of his tray was black) -- this is verified by Rikyū’s kaō [花押] in red lacquer on the bottom.

Jōō’s Matsu-no-ki-bon was made during his middle period, after he began using the fukuro-dana (the finish of this tray is better suited to the mood of the fukuro-dana than would have been one painted with shin-nuri), as a tray for his treasured chaire‡ (the karamono-nasu shown above, while not one that was owned by Jōō, measures 2-sun 2-bu in diameter; and I chose to use this photo because the Jōō-nasu and other of his chare are usually photographed resting on uchi-aka-bon [内赤盆] that were paired with them after Jōō’s death).

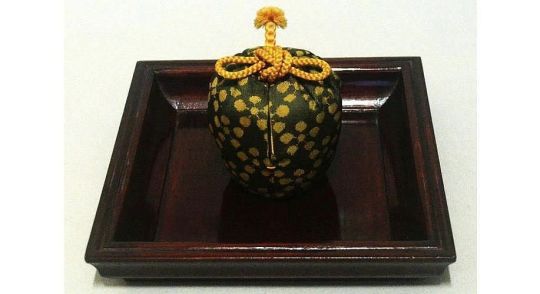

Rikyū’s tray, while (according to certain sources, though perhaps the Nampō Roku cannot be read in that way) supposedly made with Jōō’s chaire in mind, was also used to support a chū-natsume (which is also 2-sun 2-bu in diameter) -- when it contained tea that Rikyū had received from Hideyoshi**. This was done to show respect to the tea. This matter is described, albeit briefly, in the entry.

There were also Korean-made trays of approximately this size, made from pine wood and rubbed with lacquer, that appeared in Japan sometime between the middle of the sixteenth†† and the middle of the seventeenth century, and these trays were occasionally used as chaire-bon (Kobori Masakazu, for example, famously paired one of these Korean trays with the ko-Seto Yari-no-saya [槍ノ鞘] chaire). It seems that these imported trays may have become confused with Rikyū’s tray because they, too, were Matsu-no-ki-bon (which simply means trays made of pine wood).

I mention these things here, at the beginning, because it appears that the author of this entry was not at all certain about the Matsu-no-ki-bon, so his description could be confusing to anyone who was not aware of what has been written above.

Shibayama Fugen’s toku-shu shahon generally agrees with text of this entry that is found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript, though his source adds some additional identifying information to the sentence covered in footnote 3, probably in the interest of clarity‡‡. For this reason, I have included the addition in the above translation, albeit enclosed in doubled brackets as has been my practice heretofore.

The editors of the genpon text, however, decided to rewrite the text, and did so to such an extent that it needs to be discussed separately. That version will be covered in an appendix, which the reader will find at the end of this post.

__________

*The lacquer is worked into a cloth, and the cloth is used to rub the unpainted tray. This stains and waterproofs the wood, without imparting the glossiness of true lacquerware. This process is either called fuki-urushi [拭き漆], wiped-on lacquer, or suri-urushi [摺り漆], rubbed-on lacquer (the verb suru [摺る] is often translated “printing” because, in the case of traditional Japanese woodblock-prints, the back of the paper is rubbed to insure a good transfer of ink, and the same hand-motion is used when rubbing lacquer onto the tray with a cloth).

†Tame-nuri [溜め塗り] is an indeterminate mixture of black lacquer and Shunkei lacquer -- originally it was simply a mixture of whatever was left over at the end of the day, which the lacquer artist mixed and then painted on cheap bowls and trays intended for household use by the lower classes -- so the color ranged from brown to nearly black (though it usually retained the transparency of Shunkei lacquer).

‡Certain accounts state that the tray was made for the chaire known as the Jōō-nasu [紹鷗茄子]. This chaire measures just under 2-sun 2-bu in diameter.

**In fact, this appears to have usually been the case when Hideyoshi was going to visit Rikyū for chanoyu. Not only would the tea from one of Hideyoshi’s own jars have been of higher quality that that in Rikyū’s cha-tsubo, but Hideyoshi, always afraid of being poisoned by someone associated with the feared Ikkō-ichi-nen-shū [一向一念宗] (as were all chajin at that time, whether Japanese or otherwise -- chanoyu had originated as one of that Amidist sect’s methods of training in samadhi, after all), preferred to be served with tea that had been ground under his own personal supervision and then transported to Rikyū’s residence under guard, tied in Hideyoshi’s own chū-natsume. It may have been on account of these extraordinary precautions that Rikyū chose to handle this natsume of tea in the way that will be discussed in this entry.

††Perhaps Rikyū brought some of them back from the continent when he returned at the end of 1554, while others may have been collected during the invasion of the continent in 1592. And, of course, additional trays of this sort may have been brought to Japan during the seventeenth century, along with so many other things of Korean origin.

‡‡The Enkaku-ji text simply states that the tea was received from a superior, while the toku-shu shahon clarifies the matter with words that mean it was actually received from Hideyoshi himself.

¹Jōō no Matsu-no-ki-bon ha, Tsuji-dō no chaire ni sō-ō-shite mochiirare-shi nari [紹鷗ノ松ノ木盆ハ、辻堂ノ茶入ニ相應シテ被用シ也].

Jōō no Matsu-no-ki-bon ha [紹鷗の松の木盆は] this is referring to the original Matsu-no-ki-bon, the tray that Jōō created during his middle period -- as a chaire-bon for “his most prized chaire.”

According to scholars writing down through the ages, his most prized chaire are said to have been two nasu-chaire*, both of which were meibutsu pieces.

As mentioned above, this tray measures 8-sun 2-bu square, so the chaire for which it was made would have measured 2-sun 2-bu (according to the way that Jōō calculated the dimensions of his chaire-bon). The shape of the rims is based on the Gassan-nagabon [月山長盆], the tray that was used for gokushin tea†. And finally, concerning the orientation of the tray, while the modern schools seem to prefer that the grain be oriented from side to side, in Jōō’s and Rikyū’s period, at least, trays were usually oriented so that the grain was parallel to the heri of the mats. Tana-mono, on the other hand, were placed so that the grain was oriented from side to side‡.

Tsuji-dō no chaire ni sō-ō-shite mochiirare-shi nari [辻堂の茶入に相應して用いられしなり] means (this tray) is suitable to be used with the Tsuji-dō chaire.

This could be interpreted to mean that this tray was made for this Tsuji-dō chaire, but that way of understanding the text is not necessary. Unfortunately, there is no mention of a Tsuji-dō chaire in any of the historical records from Rikyū’s period** (including places where it should appear, such as in the Yamanoue Sōji ki [山上宗二記]), even though both Shibayama and Tanaka claim that this chaire was Jōō’s special treasure††.

This sentence is the same in Shibayama Fugen’s toku-shu shahon version of the Nampō Roku.

Today, most of the old “higashi-bon” [干菓子盆] actually started life in chanoyu as chaire-bon. They were repurposed as higashi-bon during the Edo period, when the general tea population came to prefer the smaller Rikyu-sized chaire-bon (since then known as ko-bon [小盆])‡‡.

__________

*Jōō owned two meibutsu nasu-chaire. The first was called the Tsukumo-nasu [付藻茄子]. This chaire measured 2-sun 4-bu in diameter, and it is said that it had previously been owned by both Yoshimasa and Shukō. This chaire is accompanied by a karamono uchi-aka-bon [唐物内赤盆] that bears Rikyū’s kaō [花押] -- though whether he actually paired this tray with the Tsukumo-nasu, or they came together during the Edo period (when many utensils became mixed up in this way) is not clear.

The second of Jōō’s two nasu chaire is today known either as the Jōō-nasu [紹鷗茄子], or the Matsumoto-nasu [松本茄子]; and since this chaire measures just under 2-sun 2-bu in diameter, it appears that the original Matsu-no-ki-bon could have been made for it. (See, however, the arguments offered in footnote 9 for an alternative theory regarding the chaire for which Jōō created his Matsu-no-ki-bon.)

While this chaire is usually displayed on a very simple uchi-aka-bon (with a black rim), this style of tray does not seem to have been used before the Edo period, so it is likely that the effect this chaire made in Jōō’s tea room was very different from what we see in contemporary photos.

Regarding photos, both of the above chaire appear almost black when examined in the subdued lighting of the cha-seki. The rather dazzling color variations seen in many photos are the result of their being photographed under intense studio lighting (and probably subsequent “photoshopping” as well). In Jōō’s tea room, the effect was most likely similar to what is seen in the photo that was included with the introductory notes at the beginning of this commentary.

†Rikyū, in several of his densho, said that Jōō created the chaire-bon in this way: Jōō took the (Gassan-)nagabon and divided it in half, and used that half tray, which represented the seat of the chaire, as a chaire-bon.

Given the dimensions of the Gassan-nagabon, Jōō’s methods were a little more complicated than simply cutting the tray in half. Dividing the nagabon in half, he used that measurement for the face of the chaire-bon, while the front-to-back measurement of the face of the Gassan bon was used for its outer dimension.

‡Therefore, when the tray was placed on the tana -- as when Jōō’s Matsu-no-ki-bon was arranged on the fukuro-dana -- the grain of the tray did not repeat the grain of the shelf.

**There is a single mention of a “Tsuji-dō” katatsuki [辻堂肩衝] in the Sōtan nikki [宗湛日記], in an entry dated Keichō 4 [慶長四年] (1599), Second Month 28th day [二月廿八日]. This entry describes a gathering hosted by Furuta Sōshitsu (Oribe), who may have been the one who gave it the name Tsuji-dō.

Another mention (in an Edo period catalog of the tea utensils mentioned in the Matsu-ya family’s several tea records) states that Jōō’s katatsuki-chaire (no name is given; and this katatsuki-chaire has not otherwise been identified by scholars) was owned (at some unspecified point in time) by Enjō-bō Sōen, a monk of the Honnō-ji. These apparently random mentions may, in fact, prove very important to identifying the chaire that is critical to this entry. See footnote 9 for a deeper dive into this line of thinking.

††It was because of this argument, which Shibayama and Tanaka were simply repeating in their commentaries, that speculation regarding the identity of the chaire for which this Matsu-no-ki-bon was created turned to the two chaire discussed above.

‡‡Unfortunately, the way to pair the tray with the chaire was forgotten after Rikyū’s death (actually, the machi-shū followers of Imai Sōkyū had never been parties to the secret), so that many chaire and chaire-bon combinations appear rather incongruous today.

²Ō-buri nari [大ブリ也].

Ō-buri nari [大振りなり] means (Jōō’s Matsu-no-ki-bon) was of the larger size.

³Kyū mo mata aru-toki hai-ryō no o-cha-biraki ni, atarashiki ni Matsu-no-ki-bon koshiraerare-shi nari [休モ亦アルトキ拜領ノ御茶ビラキニ、新ニ松ノ木盆コシラヘラレシナリ].

Kyū mo mata [休もまた] means

Aru-toki hai-ryō no o-cha-biraki ni [ある時拝領の御茶披き] means on a certain occasion when (Rikyū) was going to open the tea that he had received (from Hideyoshi)....

Atarashii ni Matsu-no-ki-bon koshiraerare-shi nari [新しいに松の木盆拵えられしなり] means he (used) a Matsu-no-ki-bon that had been newly(-made).

This is the only place where the toku-shu shahon text differs from what is found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript: Kyū mo aru-toki denka-yori o-cha natsume ni te hairyō nari, sono o-cha-biraki ni atarashiki Matsu-no-ki-bon koshiraete mochiirare-shi nari [休モ或時殿下ヨリ御茶棗ニテ拜領ナリ、其御茶開ニ新シキ松ノ木盆拵ヘテ被用シナリ]. This means “Rikyū also, on an occasion when he received a natsume of tea from His Highness, when he was going to open the tea he used a new Matsu-no-ki-bon that had (just been) made.”

While this does not really change the meaning, it does clarify that the tea was received from His Highness -- in other words, from Hideyoshi.

⁴Ko-gata nari [小形也].

Ko-gata nari [小形なり] means (Rikyū’s Matsu-no-ki-bon) is small-sized.

As mentioned in the introductory passage, this tray measures 6-sun 2-bu square.

⁵Kore ha kiji nari [コレハ木地也].

Kore ha kiji nari [これは木地なり] means this (tray) was kiji [木地], which means “bare wood” -- that is, unpainted*.

In the second kaki-ire that was appended to entry 26 in Book Six, we also read “when [Ri]kyū received a gift of tea [from Hideyoshi], even if [the tea] was only put into a lacquered natsume, depending on the occasion [the natsume might have been rested on] a white-wood tray and placed out as an hitotsu-mono so that it rubbed against its kane†.” The word used here, shira-ki [白木], means the natural color of the wood -- that is, the tray was left in an unpainted state.

That said, in the tea writings from the sixteenth century, kiji not infrequently was used to refer to wooden objects that had been rubbed with lacquer (rather than left completely untreated) -- a technique that is referred to as fuki-urushi [拭き漆], wiped-on lacquer, or suri-urushi [摺り漆], rubbed-on lacquer. So, while according to the historical records Rikyū’s tray was painted with tame-nuri (with the bottom being painted with black lacquer), it is possible that the author of this entry conflated it with this type of tray (since the wood-grain was clearly visible on Rikyū’s Matsu-no-ki-bon, as it would be on a tray that had only been rubbed with lacquer). Furthermore, there were also Korean-made pine wood trays that were rubbed with lacquer in the same way, and these had been used in Japan as chaire-bon since the sixteenth century as well. It is even possible that, since these trays typically measured around 6-sun square, the author might be thinking of one of these trays.

During the first half of the seventeenth century, Kobori Masakazu paired one of these Korean trays‡ with the ko-Seto katatsuki-chaire [古瀬戸肩衝茶入] known as Yari-no-saya [槍ノ鞘], below; and the records simply state that it was paired with a Matsu-no-ki-bon. Since the Yari-no-saya is just over 1-sun 9-bu in diameter, a Korean tray measuring 6-sun square would be a perfect match.

Hideyoshi is also said to have used a kiji tray of this sort** in his 2-mat room††, so possibly the author of this entry confused Hideyoshi’s tray with the Matsu-no-ki-bon that Rikyū used when serving the tea that had been sent to him from Hideyoshi.

___________

*While that kind of argument might have been made with respect to Jōō’s Matsu-no-ki-bon, the same could not really be said about Rikyū’s tray, which was fully lacquered.

This may be indicative of the confusion between Jōō’s tray and Rikyū’s, or the difference in degrees between a tray that was simply rubbed with lacquer versus one that was lacquered with tame-nuri: today, the trays that are being sold as Rikyū Matsu-no-ki-bon are actually copies of Jōō’s tray, while Rikyū’s Matsu-no-ki-bon is virtually unknown.

†Kyū no hai-ryō no o-cha natsume no nurimono iretaru wo sae, toku ni ōjite shira-ki no bon ni hitotsu-mono suri-gane okare-shi nari [休ノ拜領ノ御茶ナツメノヌリ物ニ入タルヲサヘ、時ニ應シテ白木ノ盆ニ一ツ物スリガネヲカレシナリ].

We should notice that the language of this kaki-ire indicates that it was inserted into to Book Six at probably the same time that the present entry was added to the collection of papers in Nambō Sōkei’s wooden chest, suggesting that this entry was intended to elaborate upon the text of that kake-ire (which spatial constraints had forced the person who added it to keep as brief as possible). Note, also, that the kaki-ire from Book Six does not specify what kind of wood was used (while something like paulownia wood could be used with impunity, pine wood could potentially become sticky, if the sap had not completely dried before the wood was worked). While nothing would have prevented Rikyū from using an unpainted tray in this way, the feeling of this episode is closer to the way people were doing things in the Edo period, rather than in his own time.

The quotation was taken from the post entitled Nampō Roku, Book 6 (26.2, 26.3): the Two Kaki-ire [書入]. URL for the post from which the quote was taken is:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/651284610199732224/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-6-262-263-the-two-kaki-ire

As mentioned above, the quote comes from the second kaki-ire -- which is continuing the discussion of mine-zuri [峯刷] placement versus overlapping a kane by one-third. Placing a natsume on an unpainted tray, and then arranging it so that it rests squarely on its kane is a special case that is more or less limited to the small room, and one that, even in that setting, should not be done frequently.

‡Historical revisionists make it a karamono-Matsu-no-ki-bon [唐物松ノ木盆], with the implication being that it was imported from China. But this is a typical Joseon period Korean tray of a sort that the Chinese would never have used.

**Pine wood, on account of the sticky resin, is not especially useful for kiji pieces. That is probably at least part of the reason why Jōō had his Matsu-no-ki-bon rubbed with lacquer -- to guard against the possibility that the tray might become sticky (even if it seemed perfectly dry when first received from the craftsman). Whether Hideyoshi’s tray was made from pine, or from some other wood, is not really clear from the historical sources.

Today, of course, paulownia wood (kiri-kiji [桐木地]) is generally preferred for kiji trays.

††This room has sometimes been confused with Rikyū’s Tai-an [待庵], leading to the modern version of that room (as a 2-mat room, rather than the 3-mat room used as a 2-mat daime, as Rikyū created it) which more-or-less imitates this sketch (in so far as possible without completely removing everything that was built by Rikyū).

The drawing on which all of this confusion was based is actually titled Kampaku-sama o-zashiki [関白様御座敷], which means “the Kampaku’s sitting room” (the writing on the right side of the drawing reads ni-jō-shiki [二帖敷], two-mat room). Hideyoshi was made kampaku in 1585, but the Tai-an was built during the summer of 1582, while Hideyoshi was avenging the death of Nobunaga at the battle of Yamazaki.

In the above drawing, the square space at the bottom of the picture is the enclosed genkan, where the tsukubai would have been installed, along with a bench-like veranda from where the guests would have moved up into the room.

==============================================

❖ Appendix: Tanaka Senshō’s Genpon Version of Entry 81.

81) With respect to the Matsu-no-ki-bon, [on an occasion when] His Highness handed down [a gift of] tea, [Rikyū] received [the tea] in a natsume⁶. At that time a newly-made [Matsu-no-ki-bon] was used -- this is the story that [Ri]kyū told⁷.

This [use of a new tray] was entirely appropriate⁸. Afterward, because it was also well-suited to the Tsuji-dō chaire, he wanted to use it [with the Tsuji-dō chaire], too⁹.

_________________________

⁶Matsu-no-ki-bon ha, denka-yori o-cha kudasareru ni, natsume ni irete hai-ryō nari [松ノ木盆ハ、殿下ヨリ御茶被下ルニ、ナツメニ入テ拜領也].

Denka-yori o-cha kudasareru ni [殿下より御茶下されるに]: denka [殿下] means (his) highness, and in the late sixteenth century always referred to Toyotomi Hideyoshi, so denka-yori [殿下より] means something (came) from Hideyoshi; o-cha kudasareru [御茶下されるに] means tea* that “came down” from (Hideyoshi) -- the use of the verb kudasareru means that something was given to an inferior from someone occupying a vastly higher status.

Natsume ni irete hairyō nari [ナツメに入れて拜領なり]: natsume ni irete [ナツメに入れて] means (the tea) was put into a natsume; hairyō nari [拜領なり] means when it was received. In other words, the tea was received in a natsume† -- which Rikyū then displayed on his Matsu-no-ki-bon, as a way to honor the tea that had come from Hideyoshi.

__________

*The honorific prefix o- [御] was used because the tea in question came from Hideyoshi.

†Some scholars interpret this to mean that the tea was put into the natsume by the host -- the person who had received the tea -- since this has customarily been the practice ever since the tea shops started selling pre-ground matcha in metal cans (apparently this practice began as early as the nineteenth century, or possibly even earlier).

This, however, belies an ignorance of historical precedent: particularly in the case of the chajin connected with Rikyū (which would have included Hideyoshi), the idea was that, after the tea leaves had been ground into matcha, it was essential that the matcha be exposed to the air as little as possible. Thus the matcha was swept from the tea mill (using a feather) and collected directly into the tea container from which it would be served -- a chaire, if it was going to be served during a temae, and a lacquered container when it was either going to be used for ordinary drinking, or when the tea was going to be sent to someone else (when grinding tea for a gathering, the rule was that the chaire should be filled completely -- so there was little empty space into which the volatile components could diffuse, since they would be lost into the air of the room as soon as the container was opened -- and any remaining tea would be put into a lacquered tea container for use as ordinary drinking tea).

Hideyoshi’s lacquer artist, Seiami [盛阿彌; dates unknown], had created what we now call the kiri-ai-guchi [切り合い口] natsume -- this is a natsume with a lid that fit so closely that virtually nothing could escape once it was closed, and it was into this kind of natsume that the tea was put prior to its being dispatched to Rikyū.

Since Jōō‘s time (according to Rikyū, Jōō created the natsume shape based on the shadow cast by a classical katatsuki-chaire), natsume had been made in two sizes. The small size was based on the ko-tsubo chaire [小壺茶入], which are commonly 1-sun 9-bu in diameter (which gave rise to the size of the ko-natsume [小棗, 小ナツメ]); this kind of natsume could hold enough tea to serve two or three guests. Meanwhile, the large natsume (ō-natsume [大棗, 大ナツメ]), which was based on the large katatsuki (these are usually 2-sun 5-bu to 2-sun 7-bu in diameter) held enough tea for five guests (this size natsume was also used when serving usucha to a large group of guests).

The medium-sized natsume (chū-natsume [中棗, 中ナツメ]) ultimately took its measurement from the Kamakura-nasu [鎌倉茄子] chaire, the chaire that was used for the gokushin-temae. The first natsume of this size appears to have been made by Seiami, though whether it was ordered by Rikyū, or by Hideyoshi (after learning the details of the gokushin-temae from Rikyū), is not clear. Nevertheless, when Hideyoshi sent tea to Rikyū (and likewise other people as well), it was always sent in a chū-natsume.

When tea was sent by Hideyoshi, it appears that the natsume was unmarked. When tea was sent on behalf of Hideyoshi (usually in response to an application submitted through one of the sadō [茶頭], tea officials), the natsume was usually inscribed (in red lacquer) with the kaō of the official who filled the container. This is why natsume featuring these red-lacquer kaō began to appear from the 1580s: the kaō was not intended to indicate that the signatory liked or favored the utensil (though this is how it was interpreted in the Edo period), but to certify who had filled the container (perhaps as a way to guarantee that there would not be “any problems” with the tea) -- since the tea had been sent in Hideyoshi’s name, after all.

Finally, as mentioned above, it is important to point out that, in the case of tea sent to Rikyū, this tea was usually intended to be used at a gathering in which Hideyoshi himself would participate -- since having it ground under his own supervision, tied in one of his natsume, and then sent under guard to Rikyū’s residence, was the only way that Hideyoshi could be satisfied that the tea had not been tampered with.

⁷Kono-goro atarashiku koshiraete mochiirare-shi to Kyū monogatari nari [此頃新ク拵テ被用シト休モノガタリナリ].

Kono-goro [この頃] means at this time (in other words, at the time when Rikyū received the natsume of gift tea from Hideyoshi)....

Atarashiku koshiraete mochiirare-shi [新しく拵えて用いられし] means a new (Matsu-no-ki-bon) was made to be used (for the display of the natsume containing the gift tea)*.

To Kyū monogatari nari [と休物語なり] means and this was Rikyū’s story.

This is basically an elaboration of the information included in footnote 3, above -- to give validity to the story that a new tray had been made by putting the words into Rikyū’s own mouth.

__________

*Obviously it would take a certain amount of time for a new tray to be made. But since the point was that the matcha had to be used as soon as possible, even if it had been a gift to the host, the delay that making a new Matsu-no-ki-bon would entail makes this story -- at least if taken literally -- difficult.

In the case of the natsume of matcha that Hideyoshi had caused to be transported to Rikyū’s house, it would have arrived just prior to Hideyoshi’s own arrival, and, of course, a delay caused by making a new tray would be out of the question.

We see here an example of how these stories became more and more elaborate over the course of the Edo period, while also moving farther and farther from the actual truth of the episode on which they were based.

⁸Motto mo no koto nari [尤ノ事也].

Motto mo no koto [尤ものこと] means that (the providing of a new tray upon which the natsume of gift tea would be handled) was entirely appropriate.

⁹Sono-ato, Tsuji-dō no chaire ni sō-ō tote mochiirare-shi nari [其後、辻堂ノ茶入ニ相應トテ被用シナリ].

Sono-ato [その後] means after that, sometime later, at a later date.

Tsuji-dō* no chaire ni sō-ō tote mochiirare-shi nari [辻堂の茶入に相應とて用いられしなり] means because it was found to be well-suited to the Tsuji-dō chaire (Rikyū) wanted to use it (with that chaire) as well.

In other words, according to this version of history, pairing this tray with the Tsuji-dō chaire did not occur until some time after the Matsu-no-ki-bon had been made -- that it was not that the Matsu-no-ki-bon was created as a chaire-bon for the Tsuji-dō chaire, but that the Tsuji-dō chaire was only later paired with this tray because it was found to be suitable.

As mentioned above, the Tsuji-dō chaire has not been identified by modern scholars -- even though both Shibayama Fugen and Tanaka Senshō state that it was a greatly treasured piece. Because Shibayama says that this chaire was Jōō’s cherished (hizō [秘藏]), precious object (ki-hin [貴品]), it must have been widely known -- indeed, it must have been a meibutsu-chaire -- yet there is no trace of the name in any of the historical documents dating from his period.

To further complicate matters, it appears that there was also an oki-hanaire and a kōgō that were also called Tsuji-dō -- and often the records from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries do not always specify what sort of utensil is being referred to by the name Tsuji-dō. For example, in the (Tennōji-ya kai-ki [天王寺屋會記],) Sōtatsu hoka-kai-ki [宗達他會記], in the entry for the 17th day of the Eleventh Month of Tenbun 20 [天文廿年] (1551), Sōtatsu (Tennōji-ya Sōkyū’s father) records toko Tsuji-dō, ko-ita ni, miyama-shikihi [床 辻堂、小板ニ、みやましきひ]. The nature of this Tsuji-dō is not specified, but since miyama-shikimi [深山樒] is the name of a flower (Japanese skimmia [Skimmia japonica]), and ko-ita [小板] is the earlier name for an usu-ita [薄板], the board (of the sort called yahazu-ita [矢筈板] today) that is placed under a hanaire, we can conclude that this particular Tsuji-dō must have been a(n unidentified) hanaire. Nevertheless, certain scholars still wonder whether it might somehow have been the chaire that was displayed in the tokonoma on this occasion (with one going so far as to explain that the flowers were simply rested on the empty chaire -- without any water inside -- during the shoza; and then it was filled with tea and so used to serve tea during the goza).

That said, there is one mention of a Tsuji-dō katatsuki [辻堂肩衝] in the Sōtan nikki [宗湛日記], the tea diary of Kamiya Sōtan [神屋宗湛; 1551 ~ 1635], in an entry dated Keichō 4 [慶長四年] (1599), Second Month 28th day [二月廿八日], which describes a gathering hosted for three guests (including Sōtan) by Furuta Oribe, probably on behalf of Toyotomi Hideyori [豊臣秀頼; 1593~1615]:

katatsuki ha, Seto nari, kusuri ki ni shite, kudaharu, Tsuji-dō to mōshi nari, fukuro ha donsu, himo/tsukari kuranai nari

[肩衝ハ、セト也、藥黄ニシテ、下ハル、辻堂ト申也、袋ハ緞子、緖ツカリ紅也].

“The katatsuki [was] Seto. The glaze was yellowish[-brown]. [It] was handed down [from Hideyoshi]. It is [called] Tsuji-dō. The fukuro was made of donsu; the himo and stitchings were crimson.”

As this chaire was (according to the Matsu-ya meibutsu-shu [松屋名物集], a sort of catalog of the utensils mentioned in the Matsu-ya kai-ki [松屋會記]) owned by Hideyori (having been part of his father Hideyoshi’s collection), Furuta Sōshitsu was probably acting as the host in his stead, much as had been the practice done under Hideyoshi. It is not clear who gave the chaire the name Tsuji-dō (though it is the kind of name that Oribe often bestowed on tea utensils, so the suggestion for the name may have come from him).

Curiously, there is one meibutsu-chaire that has been associated with a (small) Matsu-no-ki-bon since Rikyū’s period. It is an old Seto chaire, and was part of Hideyoshi’s collection (as were many of Jōō’s other treasures). The tray was apparently provided by Rikyū, who then used it when serving tea to many of Hideyoshi’s guests during his last year of life (as recorded in the Rikyū hyakkai-ki [利休百會記]). In this kaiki, the chaire is simply described as “a katatsuki on a tray,” without any sort of name at all -- yet since it was used when entertaining some of Hideyoshi’s most important guests, it clearly was understood to be a very special chaire.

Today this chaire is known as the Enjō-bō katatsuki [圓乗坊肩衝] -- but this name is historically meaningless, in so far as any association with Jōō is concerned (in fact, the name Enjō-bō, for a katatsuki-chaire, makes its first appearance around 1660, in a book called the Gan-ka meibutsu-ki [玩貨名物記] -- this book is simply a list of the famous tea utensils of the day, with no descriptions at all), because it derives from the name of the monk Enjō-bō Sōen [圓乗坊宗圓; dates unknown], a disciple (as well as a son-in-law) of Rikyū, and the person who salvaged this chaire (as well as the one known as the Honnō-ji bunrin [本能寺文琳]) from the ashes of the Honnō-ji (Sōen was a monk of that temple), after the fire in which Nobunaga died -- meaning that this chaire had likely been one of Nobunaga’s treasures. (Nobunaga was resting in the Honnō-ji temporarily, to purify his mind after several years of conflict, so it likely that he only brought those few tea utensils than truly gave him the most pleasure.)

This chaire had been damaged in the fire, and it was repaired, with lacquer, by Sōen.

Rikyū’s first recorded use of this chaire (at which time he seems to have placed it on his Matsu-no-ki-bon) was on the 18th day of the Eighth Month of Tenshō 18 (1590), which was the second occasion on which Rikyū hosted a chakai in Kyōto after he and Hideyoshi returned from Odawara (suggesting that Hideyoshi sent the chaire to Rikyū as an expression of thanks for his services during the siege of Odawara). He used it for the second time on the 13th day of the Ninth Month, when he served tea to Hideyoshi.

Rikyū was placed under house arrest from the 23rd day of the Ninth Month until the 23rd or 24th day of the Tenth Month (on account of the chakai that he hosted for Kokei Sōchin on the 14th day of the Ninth Month, the morning of the day when Kokei had been ordered to quit Kyōto and go into exile in Kyūshū). The house arrest was lifted around the 24th of the Tenth Month, and he hosted a chakai for two important daimyō from Kyūshū (whose assistance would be crucial to the success of the invasion of the continent), at which he used his own Shiri-bukura chaire (Rikyū seems to have become acquainted with these men during Hideyoshi’s stay in Kyūshū, in 1587, so perhaps he wanted to serve them using his personal tea utensils on this occasion, to encourage a feeling of intimacy).

The Enjō-bō katatsuki was used at gatherings on the 27th of the Tenth Month; the 2nd, 6th, 11th, 19th, 21st, and 22nd of the Eleventh Month; on the 4th, 7th, 11th, 18th, 24th, and 27th of the Twelfth Month of Tenshō 18; on the 26th (when he again used it while serving tea to Hideyoshi) and 27th days of the First Month of Tenshō 19; and Rikyū used this chaire for the last time on the 3rd day of the Intercalated First Month of Tenshō 19.

In all, out of the 92 chakai that are documented in the Rikyū hyakkai-ki [利休百會記], he used the Enjō-bō katatsuki some 20 times, mostly on occasions when he was serving tea to people who were deeply interested in chanoyu.

The Enjō-bō katatsuki was classified as an ō-meibutsu [大名物] by Kobori Masakazu, who considered it to be one of the greatest of the old Seto chaire. In the Taishō mei-ki kan [大正名器鑑], only four chaire are associated with a Matsu-no-ki-bon, and only two of those are katatsuki: this chaire and the one known as the Yari-no-saya [鑓ノ鞘 ]. But while the Yari-no-saya katatsuki measures 1-sun 9-bu in diameter (and so would be too small for both Jōō’s Matsu-no-ki-bon and the Matsu-no-ki-bon that Rikyū used for the chū-natsume), the Enjō-bō katatsuki measures between 2-sun 2-bu and 2-sun 2.3-bu in diameter, which is the perfect size to be used on both Jōō‘s and Rikyū’s Matsu-no-ki-bon.

It is important to note that once the name Enjō-bō katatsuki starts to appear in the records, the Tsuji-dō name disappears. As for the seeming confusion over the names, this would not be the first chaire to be misidentified in the Nampō Roku -- nor in other documents from the Edo period†.

About all of this, Tanaka Senshō wrote:

I-jō no genpon de miru to, Matsu-no-ki-bon ha Rikyū ga kononda bon de aru. Sore ha, denka-yori o-cha wo chōdai-shita-toki, natsume ni irete itadaita. Sono natsume wo atsukau tame ni, Matsu-no-ki-bon wo seisaku-shite, bon-date ni shita. Izure natsume no koto-yue, shōshō ō-buri no bon wo tsukutta de arau. Shikaru ni, sono-ato, Tsuji-dō no chaire ga, chōdo sono ōki-sa ga tekitō de aru tote, sono Tsuji-dō no chaire wo mo, kono Matsu-no-ki-bon de atsukauta.

Kaku kaisu-beki de, honbun de yomu to, Jōō no Matsu-no-ki-bon to iu ga ari, kore ha Tsuji-dō no chaire ga sō-ō-suru tote shiyō-serareta ga, kono bon ha zuibun ōkii. Shikaru ni, denka-yori hairyō no chaire-biraki ni, sara ni, Matsu-no-ki-bon wo koshiraerareta. Kore ha ko-gata de kiji de aru to. Kore ha hatashite izure no setsu wo shinzu-beki ka.

Yo ha, genpon no natsume to iu ni omoki wo oki, ō-gata no Matsu-no-ki-bon wo seisaku-shita ga, chōdo, sono-ato, Tsuji-dō no ō-chaire ni sō-ō-suru tote, sono Matsu-no-ki-bon wo ri-yō-serareta to kai-suru no ga seikai de ha nai ka to omou. Matsu-no-ki-bon ni dai-shō aru ha, yo mo jikken-shite shitte-iru. Shunkei-nuri no hon-ji ha ō-gata de ari. Nezu bijutsu-kan ni te mita no ha, ko-gata de, nuri mo kuroku, kiji to ha ienu-hodo de aru. Kono kata ga furui to omou.

[以上の原本で見ると、松木盆は利休が好んだ盆である。夫は、殿下より御茶を頂載した時、棗に入れて頂いた。其棗を扱ふ為めに、松木盆を製作して、盆点にした。何れ棗の事故、少々大振りの盆を作ったであらう。然るに、其後、辻堂の茶入が、丁度其大さが適当であるとて、其辻堂の茶入をも、此松木盆で扱ふた。

[斯く解す可きで、本文で読むと、紹鷗の松木盆と云ふがあり、是は辻堂の茶入が相応するとて使用せられたが、此盆は随分大きい。然るに、殿下より拝領の茶入披きに、更に、松ノ木盆を拵へられた。是は小形で木地であると。これは果して何れの説を信ずべきか。

[予は、原本の棗と云ふに重きを置き、大形の松木盆を製作したが、丁度、其後、辻堂の大茶入に相応するとて、其松の木盆を利用せられたと解するのが正解では無いかと思ふ。松の木盆に大小あるは、予も実見して知って居る。春慶塗の本地は大形であり、根津美術館にて見たのは、小形で、塗りも黒く、木地とは云えぬ程である。此方が古いと思ふ].

“Looking at the genpon text above, the Matsu-no-ki-bon was Rikyū’s favorite tray. So, when His Highness gave [Rikyū] tea, he received it in a natsume. When dealing with that natsume, [Rikyū] made a Matsu-no-ki-bon and used it [to perform] bon-date [with the natsume]. [The tea container] was always a natsume, so under these circumstances, a slightly larger tray would have had to be made [in order to accommodate the natsume‡]. However, later on, he decided that the Tsuji-dō chaire was just the right size; so when using this Tsuji-dō chaire, too, it was also handled on this Matsu-no-ki-bon.

“In order to resolve this conundrum, after reading the original text, [I] obtained [a copy of] what is referred to as Jōō’s Matsu-no-ki-bon, on the grounds that the Tsuji-dō chaire would be suitable for use on it. But this tray [proved to be] too big**. Consequently, when the chaire that had been received from His Highness was going to be used, it would follow that a [new] Matsu-no-ki-bon would have had to have been made. This one, then, was smaller, and made from unpainted wood. Therefore -- as [I] was afraid might be the case [given so many different stories] -- which of these should we believe?

“As for me, [I think] we should place greater stock in the [story of the] natsume in the genpon [text]. So, after making a large-sized Matsu-no-ki-bon, I found that it was suitable for the large Tsuji-dō chaire††, so [I] concluded that might this not have been the one [referred to in the story]? I know for certain that there are both a large and a small Matsu-no-ki-bon. The one originally finished with Shunkei-nuri is the large one; while the one I saw at the Nezu Museum was smaller in size and had darker lacquer, so it could hardly have been called kiji. I think this [smaller] one is the older.”

I decided to include Tanaka’s remarks here not because they will help the reader understand this matter more clearly, but because they are illustrative of the general confusion that has surrounded the two versions of the Matsu-no-ki-bon since the Edo period; and, in light of the that period’s teachings regarding the way that things should contrast and so forth -- none of which is anything more than nonsensical obfuscation, intended to mask the ignorance of the masters regarding the reasons why things are as they are (with Rikyū’s death, the teachings on kane-wari and the reason why things were given the sizes that they were, all of these teachings were lost as the tea world shifted allegiance to the machi-shū followers of Imai Sōkyū and Furuta Oribe) -- it is hardly surprising that confusion still reigns supreme in the world of tea to this day.

__________

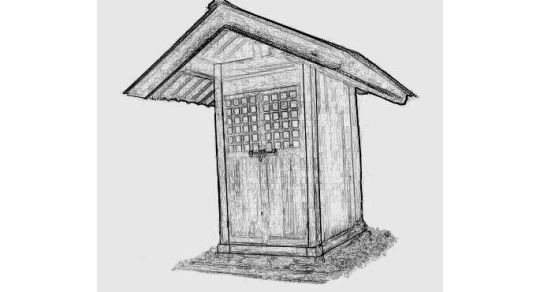

*A tsuji-dō [辻堂] is a small structure (the floor of which might be no more than a meter square), sometimes little more than four wooden pillars supporting a modest roof, in which an image of the Buddha (for example, the Buddha Jizō [地藏], the protector of travelers, is common; other times their contents may be associated with Shintō beliefs) has been enshrined

When enclosed by walls (and a pair of hinged doors in front), the proportions and profile are often strikingly similar to that of the Enjō-bō katatsuki [圓乗坊肩衝], so it is completely believable that the name could have been given to this chaire at some time before, or after, the catastrophe at the Honnō-ji.

†Though it is an old Seto katatsuki -- and one of exceptional quality -- it appears that no information about this chaire from its previous life survived the fire at the Honnō-ji -- including the name by which it was known theretofore. Even the matter of its having been owned and treasured by Nobunaga has been called into question by some scholars (though, since Nobunaga is known to have died during chanoyu, and it was found in the ruins of the shoin where the service of tea was taking place, there is no other logical reason why the chaire would have been found where it was unless it was being used during that service -- the conventions of that time, which date back at least as early as Yoshimasa, would have had the bunrin-chaire used for koicha, and the katatsuki used as the container for usucha), since there is literally nothing in the historical record from before the fire.

‡Why the tray would have needed to be large is not clear. The chū-natsume measures 2-sun 2-bu in diameter, and Rikyū’s Matsu-no-ki-bon measures 6-sun 2-bu square. Thus, the tray is exactly 2-sun larger than the natsume on all four sides. This accords with Rikyū’s idea, since it allowed the chawan to be placed beside the bon-natsume just as if the tray did not exist.

In other words, Rikyū could perform the temae with the minimum number of concessions and modifications (to the tray) as possible -- because Rikyū preferred to always perform the temae in the same way. (This idea came from his having been initiated into chanoyu through gokushin tea, since in that style of tea the temae is always the same. It was a feature of the machi-shū style of tea, the kind of tea that Jōō formalized during his middle period, and which was carried on by Imai Sōkyū and his machi-shū followers, that each special variety of utensil should require a different kind of temae. This approach persists in modern-day chanoyu.)

**Tanaka, who had only been exposed to Sen family conventions, did not understand that Jōō's tray was supposed to be 3-sun larger on all four sides than the chaire that was placed on it. Thus, though Jōō's Matsu-no-ki-bon measures 8-sun 2-bu square, it was intended to be used with a chaire that was 2-sun 2-bu in diameter. While this would have seemed excessive to anyone who had only seen the small chaire-bon used by the Sen family, it also indicates that Tanaka was not really sensitive to the demands of the bon-date temae. While it is possible to place the chakin on the smaller trays (we must remember that the Sen family had no rules regarding how the size of the chaire should relate to that of the tray, so they usually used a ko-bon [小盆] that was 6-sun across irrespective of the size of the chaire that was going to be placed on it), the chakin tends to be squeezed into one corner, wedged in between (and in danger of touching) the chaire. And while Rikyū’s way of pairing a chaire with a ko-bon did provide just enough room, Jōō's tray has so much room that the chakin can be placed on it easily -- far enough from both the corner and the chaire that there is no danger. This was because Jōō took the nagabon that was used with the daisu as his guide in this matter.

††Tanaka is relying on the conventions of his time, which said that a large chaire should be placed on a large tray, and a small chaire on a small tray. Of course, this shows his ignorance of the way that Jōō matched his trays to his chaire; but that could not be helped, since he was living in an environment that already was intent on discouraging questions. However, since the school that he founded supposedly teaches the gokushin-temae -- where a 2-sun 2-bu chaire (originally, the Kamakura-nasu [鎌倉茄子]) uses the Gassan-nagabon as its chaire-bon during the temae (which tray measures 1-shaku 3-sun 2-bu by 9-sun 2-bu across the rims) -- it is difficult to understand how he came to this conclusion. In fact, whether Jōō created the large Matsu-no-ki-bon for the Jōō-nasu or the Enjō-bō katatsuki (= Tsuji-dō katatsuki), since both of these chaire were essentially 2-sun 2-bu in diameter, the resulting tray would have had to be the same size as what we see now...and neither of these chaire can be described as “large.”

==============================================

◎ If these translations are valuable to you, please consider donating to support this work. Donations from the readers are the only source of income for the translator. Please use the following link:

https://PayPal.Me/chanoyutowa

1 note

·

View note

Text

Antique Owan lacquerware.

+SHOP+

Urushi (Japanese Lacquer) has high antibacterial properties and makes the wood strong.

Urushi can be repeatedly extracted from a single tree, making it an eco-friendly varnish.

Wajima-nuri is a lacquer ware made in Wajima City, Ishikawa Prefecture.

It is characterized by its unparalleled care and attention to detail in the lacquering process, which involves more than 20 processes and a total of 75-124 times of careful manual labor before it is completed.

Although it is a labor-intensive and costly process, Wajima-nuri is characterized by the fact that the technique has been preserved without placing emphasis on inexpensive production.

#owan bowl#Japanese antique#urushi lacquerware#Japanese tableware#kaiseki food#Japanese food#Japanese restautant

0 notes

Text

graveflower

#ARTIST IS#urushi nuri#accel world#kuroyukihime#fairy#evil fairy#wall paper#wings#dark fairy#monochrome#weebcore#animecore

160 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Les plus belles œuvres des artisans japonais.

Boîte en laque : bois avec incrustation de nacre - Dimensions : 14 x 14,9 x 21,3 cm.

Période Meiji jidai 明治時代 (1868-1912).

281 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Urushi Low Cabinet by Max Lamb,

Wajima-nuri, as lacquer products are famed for superior durability. Their rigorous production involves layer upon layer of increasingly fine base coats, with careful drying, sanding and smoothing between each layer, until the final glossy top layer is applied.

Cypress, Waijima-Nuri Urushi Lacquer,

950 x 400 x 900

Produced for Gallery Fumi

#art#design#furniture#cabinet#urushi#max lamb#cypress#waijima-nuri#lacquer#Millwork#black#minimalism#wajima#japan

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bonsai or flower basin made of forty scabbard pieces, Unknown Japanese, late 19th century, Minneapolis Institute of Art: Japanese and Korean Art

forty sections of several antique sword scabbards (saya) set about the basin; basin of copper inserted in a wood base with surrounding belts of tiger-striped, ebony-like hardwood; between belts are alternating sections of 19 scabbards made of different materials; handles on each end are the actual knobs (kurigata) to attach a braided cord (sageo) to the scabbard; see Notes for descriptions of each scabbard piece (from exhibition catalogue) Forty sections of several antique sword scabbards (saya) were set about the circumference of this basin (suiban) made for flower arrangements or bonsai display. A removable copper basin was inserted in a wood base with surrounding belts of tiger-striped, ebony-like hardwood. Between these belts are alternating sections of 19 scabbards made of different material and the handles on each end are the actual knobs (kurigata) to attach a braided cord (sageo) to the scabbard. On some, utility knife (kozuka) openings are clearly visible. Starting from one of the handles, the different scabbard pieces are: plain black lacquer (kuro rōiro-nuri), glossy-brown "insect-eaten" lacquer (cha-urumi mushikui-nuri), glossy-brown stone surface lacquer (cha-urumi ishimeji-nuri), black burnished shark skin lacquer (kuro samegawa togidashi), unknown type using crushed abalone shell, lacquer in thin parallel lines (ichibu kizami urushi-nuri), brown burnished shark skin lacquer (samegawa togidashi), lacquer with crushed abalone shell and flower pattern (hanamon aogai miji-nuri), rare shark skin on the back (kairagi same), wrapped brocade (nishiki tsutsumi), black "insect-eaten" lacquer with auspicious clouds (zuiunmon kuro urushi mushikui-nuri), sandalwood imitating lacquer (byakudan-nuri), imported rare lizard skin, lacquer with crushed abalone shell (aogi miin-nuri), strip motif lacquer (shuroke fuemaki-nuri), pronounced "insect-eaten) lacquer (mushikui-nuri), and red lacquer with willow pattern (shu-urushi yanagimon nuri).

Size: 3 3/4 × 24 3/16 × 13 1/16 in. (9.53 × 61.44 × 33.18 cm)

Medium: Wood, lacquer, copper and other metals, abalone, lizard skin, shark skin

https://collections.artsmia.org/art/121538/

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seiko Presage Urushi Byakudan-nuri Limited Edition SPB085 - HODINKEE Shop

0 notes

Text

Lacquerware/Urushi

■Soup bowl

Joboji Urushi(Ninohe, Iwate)

1 year has passed since I started using.

The surface colour has become brighter and glossier.

■Chopstick

Tsugaru Nuri(Tsugaru, Aomori)

I made it myself at Tsugaru han Neputa village in Hirosaki, Aomori.

The process of filing the surface to make the different colours in deeper layers emerged was really fun.

My daily utensils.

漆器

■汁椀

浄法寺漆(岩手県二戸市)

使い始めて1年が経ち、色がより明るくなり、艶も増してきました。

■箸

津軽塗(青森県津軽地方)

弘前にある「津軽藩ねぷた村」で手作りしました。

表面を研いで、下の層にある色を出していく工程がとても楽しかったです。

毎日をともにする道具です。

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

TIME+TIDE: Sublime Subdials - The Seiko Presage Urushi Byakudan-nuri Limited Edition SPB085

Editor’s note: Can you judge the success of a watch’s overall aesthetic based purely on its subdials? If you could, then this Seiko Presage Urushi Byakudan-nuri Limited Edition SPB085 would be an instant success. The calendar subdials of this watch, located at three and six o’clock, feature a gorgeous deep red tinge that is created through a process called the Byakudan-nuri technique. It makes for a very handsome look indeed, and it’s no wonder why this watch sold out so quickly when it went on sale late last year.

Over the last few years, Seiko has made a habit of releasing limited editions with exceptional enamel dials at very reasonable prices. First, there was the Moonlit Night, then the Shippo enamel, and now, the Urushi Byakudan-nuri...

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A smaller sibling of the pen I showed some time ago. Piccolo size, red metallic kawari-nuri. Some pens are very difficult to show on pictures. Lenses, light, polarizing filters, a lot of time, but still showing the depth of some urushi techniques is simply impossible. Some pen change a lot with light. Some look best in strong daylight. Some, and those are rare, in almost darkness. Urushi is fascinating. . Bock nib. Available. . —— Most pens I show here are for sale. Contact me through direct message here or email: [email protected]. I do not have a webshop or a big stock. Some available pens I show on my website, usually after a week or two from presenting them here - link in bio. —— . #japaneselacquer #urushilacquer #japanart #蒔絵 #漆 #fountainpen #calligraphy #urushi #nakaya #danitrio #namiki #urushifountainpen #japanlacquer #tamenuri #tamenuristudio #vulpen #styloplume #万年筆 #estilográfica #handmade #penmaking #handwriting #pencollector #penmaker #penforsale #pensforsale (at Warsaw, Poland) https://www.instagram.com/p/CeFICtjjPCC/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#japaneselacquer#urushilacquer#japanart#蒔絵#漆#fountainpen#calligraphy#urushi#nakaya#danitrio#namiki#urushifountainpen#japanlacquer#tamenuri#tamenuristudio#vulpen#styloplume#万年筆#estilográfica#handmade#penmaking#handwriting#pencollector#penmaker#penforsale#pensforsale

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This is a Yotsubishi Kawari-nuri sakura (cherry) bark pattern urushi coated fountain pen c. 1955-1959, shown open so the filler can be seen. The cap, barrel and section are all coated with urushi lacquer and finished with the sakura (cherry) bark pattern so that the artwork flows over the entire pen. Japanese cherry tree bark has a distinctive pattern and is featured in wooden objects, such as boxes, frames, and vases. The free form artwork on this pen is intended to recreate the pattern using the red urushi lacquer base and contrasting elements. Kawari-nuri is not considered a maki-e technique, but means free patterns, so the artist may decorate the urushi surface using new ideas including altering the surface with patterns, textures or swirls, adding colors, or other decorations outside traditional maki-e. Kawari-nuri artwork on pens is not likely to be signed by the artist. It is a squeeze type filler, possibly aerometric (which would require a feed tube), which dates the pen to the 1950s, following the design of the Parker 51 Aerometric. The trim is gold filler. The nib is a warranted 14 karat gold number 4 size nib. The pen is on the large size, at 5 1/4 inches long and quite broad. Ishi-Shoten, also known as Ishi & Co., was established in Tokyo in 1925 by pen maker Yoshinosuke Ishii. Following the lead of Pilot, who began making maki-e pens in the 1920s, Ishi-Shoten, though a small company with initially as few as ten workers, competed by making inexpensive maki-e pens. Ishi-Shoten used the four diamond trademark, yotsubishi in Japanese, and the mark can be found on the clip top on most pens. In reference materials, on the pens, and in catalogs, there are three spellings, Yotsubishi, Yotubisi, and Yotubishi. The company ceased operations in 1984. #pencollecting #fountainpen #yotsubishi #yotubisi #urushi #aerometric #parker51 #kawarinuri #makie #sakura #cherry #artpen #penhero https://www.instagram.com/p/B_qNshajyai/?igshid=44j4z1m3albu

#pencollecting#fountainpen#yotsubishi#yotubisi#urushi#aerometric#parker51#kawarinuri#makie#sakura#cherry#artpen#penhero

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pen making and lacquer painting have strong connection to my calligraphy. I make my own writing tools, use them and sell them to penmen around the world. These are some new Urushi finished pens and inkwell holders I have just completed, using varied techniques like Maki-e (painting with gold and silver, Rankaku-nuri (eggshell inlay), Raden (mother of pearl inlay), etc. Chekc out my other Instagram @huyhoangdao.pen . #huyhoangdao #calligraphy #penmanship #handwriting #lettering #typography #flourishing #birdflourishing #copperplate #spencerian #pointedpen #obliqueholder #iampeth #vsco #photography #urushi #lacquerpainting #japaneselacquer #漆 https://www.instagram.com/p/B2iwOKdBNyU/?igshid=d69xhiww6tdr

#huyhoangdao#calligraphy#penmanship#handwriting#lettering#typography#flourishing#birdflourishing#copperplate#spencerian#pointedpen#obliqueholder#iampeth#vsco#photography#urushi#lacquerpainting#japaneselacquer#漆

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

SARW045 #seiko #presage #watch #watchoutz #watchoutzhk #watchuseek #black #blackdial #brownaccents #goldaccents #dresswatch #leatherstrap #lacquer #sarw045 #sapphire #magneticresistant #superhardcoating #6r15 #automatic #magneticresistant #lacquerdial #specialedition #limitededition #limitedto2000pieces #byakudan #nuri #byakudannuri #rare #hardtofind #urushi (at Watch Outz 注目時計) https://www.instagram.com/p/ByE6X-9Hdsf/?igshid=1ekt61bf9c6z4

#seiko#presage#watch#watchoutz#watchoutzhk#watchuseek#black#blackdial#brownaccents#goldaccents#dresswatch#leatherstrap#lacquer#sarw045#sapphire#magneticresistant#superhardcoating#6r15#automatic#lacquerdial#specialedition#limitededition#limitedto2000pieces#byakudan#nuri#byakudannuri#rare#hardtofind#urushi

1 note

·

View note