Text

Why is there

Why is there

cat hair

on my chair?

Oh yes---

it is because

the cat often

sits there.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le soldat

Le soldat

mange le menu.

Est pourquoi pas?

Le printemps

est venu.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Snow

A puffy snowy rooftop

and a snow desert.

Whenever I see

that much snow

I think:

"Wow---that is

a lot of snow."

1 note

·

View note

Text

From the comments section

this song

rips tears in me

every time I listen to it

...oh God

how these scoundrels

make a mockery

of this country

wet with the blood of the lion-herted

so many

hundreds of years

Just4uAmnda at Grigore Lese. Canta cucu-n Bucovina!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Going about with a toothbrush

Going about with a toothbrush

in your bag

you get to have

very particular experiences.

To reach inside your bag

and clutch the tip, still wet,

of the toothbrush

is a strange sensation.

To take out your pen

and notice you've actually

put your toothbrush on the table

is funny.

To brush your teeth

in the bathroom at work

before leaving for the dentist

is, well---

you can guess.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

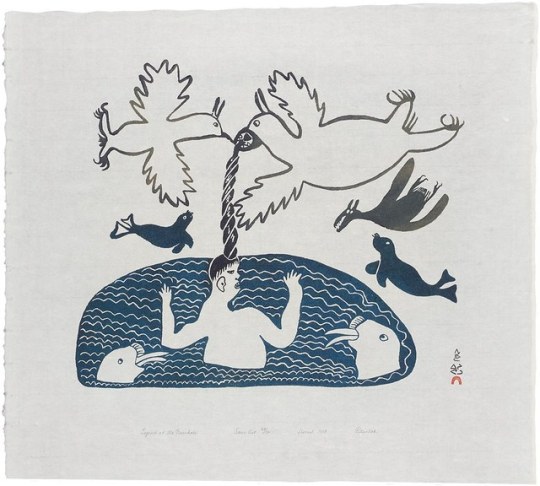

Pitseolak Ashoona (Inuit, 1904–1983), "Legend of the Narwhal," 1968. Kinngait, Nunavut, Canada. 26/406

https://twitter.com/SmithsonianNMAI/status/893656157608222720

In the very earliest time,

when both people and animals lived on earth,

a person could become an animal if he wanted to

and an animal could become a human being.

Sometimes they were people and sometimes animals

and there was no difference.

All spoke the same language.

That was the time when words were like magic.

The human mind had mysterious powers.

A word spoken by chance might have strange consequences.

It would suddenly come alive

and what people wanted to happen could happen—

all you had to do was say it.

Nobody could explain this:

That’s the way it was.

—Nalungiaq (Netsilingmiut Inuit) From "Songs and Stories of the Netsilik Eskimos: Based on Texts Collected by Knud Rasmussen on the Fifth Thule Expedition, 1921–1924," edited by Edward Field

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

From the comments section

madness during that time...

when the evening of surprises came

grandma'ma huddled over the tv,

a black-and-white snagov

I remember perfectly,

the back panel heated

because of how long she kept it on

until 23:00 or so

when the show ended :))

good times,

we had money back then,

everything was cheap,

gasoline was 2,5 lei per liter

anyway no more than 3 lei,

everything worked well,

you could make good money abroad too,

whereas now

woe is us,

inflation,

money on stop,

and so on and so forth

cristian marius at Surprize Surprize generic 2003 Cristian Geaman

1 note

·

View note

Text

From the comments section

I like folk music

if I go to school

and put on a song

from this mix

immediately they say

cut it out

because they say

these are all

they're all stupid

but I like

very much

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

Florin Penes at Mărin Cornea – Ecaterino, Eşti Damă Bine! (full album)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

So much depends on

I watch with some trepidation

the aluminium wings

getting defrosted.

Has no one thought of

making airplanes

with feathers?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Humans Were Born Free but Everywhere They Are in Peer Groups

That’s Rousseau, right? Replacing ‘chains’ with ‘peer groups’ - clever one, Dekeneu. Megalike.

Of course, Rousseau’s slogan is sweet, but also full of lies. Perhaps not the most obvious one is that not everyone is in chains, and that some of us actually hold the keys to other people’s chains. No, not like in Titanic, when Rose finds the key to Jack’s handcuffs only to plunge into a tear-jerking adieu, but like in a much more intimate (though faceless) relationship – that between, say, a sweatshop worker and a consumer of her labour. And that’s just the tip of an iceberg we can actually see – wait till we get past the Arctic Circle (and by the way, we’re full speed ahead to the North Pole, baby). In the world we live in (and here I’ve included you, reader, fellow citizen of the not so vast Western urban privileged universe), we hold the keys to a lot of chains, and we don’t even know it. Of course, someone else has the keys to ours – that’s the rule: no one holds the keys to their own chains.

Yet chains are not necessarily a metaphor for economic relationships. Cut to the most obvious lie: man was not born free (and women even less so). We are born in societies – even if you’re Tarzan, in which case you are born in a society of apes, which is not that different. In any case, you are brought up in a group of people, and any group of people has rules, a shared past, a way of dealing with things from dying to cooking food, a certain way of looking at life.

To an outsider, these are walls and enclosures, dogmas, rules which the fresh human has to learn, obey, trespass, eventually come to terms with. To an insider, they are the invisible but all-important threads that give meaning to one’s life in the group – that they might not exist is unthinkable because they are what makes living together possible and, at times, bearable.

To us, honourable citizens of a recent universe, readers and writers of this blog, they are chains. We see these ways of doing things (whether they belong to our parents’ generation or to an Amazonian tribe) as strictures, yet another set of superstitions we have to liberate ourselves from to get to that pure realm of individuality, where we might be finally free. Free to do what? Free to be ourselves, man! Yet when you do shake off the shackles of social conformity and finally plunge into this pure realm of personal freedom you see that you are not alone. Millions of other people about your age, with similar habits, reading the same blogs, are here, too, also looking for their individuality after throwing off the shackles of their own tribes. Soon enough, you’ll see patterns beginning to emerge in this brave new peer group, and you’ll learn that there are right ways to express your individuality, and there are wrong ways, and the latter are severely frowned upon by the other freemen. Back to square one, fellow tumblrist – society throws chains upon you from the day you are born, by the very fact that you have to behave in ways that you didn’t vote for.

Yet chains don’t just bind us down – they can also bind us to one another, and on a dark night, when the wind is howling and the path is doubtful, tying myself securely to others is actually the only way to push ahead and not get lost. Protein chains are what prevents your body from dissolving into a puddle of tofu chowder. DNA also comes in form of chains, and you didn’t vote for that either, but voila and alas, it makes you who you are. But ah, I too am a child of my century, and I myself find it difficult to square the rules that binds any society in history with the dollop of initiative, agency, and individuality that each of us has and wants to manifest in this world.

This is how the conversation went between me and Master Freevariable one night, and we wondered whether we can be truly free. Mind you, this was not just an idle exercise in unanswerable questions – it does matter a lot in most branches of research: economy, history, anthropology, social policy etc. in ways that you, amiable reader, are too intelligent not to see. As an explorer of mentalities in the pre-modern societies, I am always quick to caution that things we think are normal or natural are actually the workings of our own chains, and what seems to us ‘weird’ or uncanny in past ages or non-Western societies is just their chains rattling against ours. Yet individuals always have a choice, after all, to obey or disobey the rules, and there is always agency in, say, artistic creation however steeped in an unchanging tradition it may be.

So here is an attempt at trapping in words this squared circle. Actually, we’re talking about two tightly knit conundrums: 1. how can there be change in mentalities, practices, behaviours etc. at all if all people in a certain society behave only according to the rules of that society? And 2. how come all people have personal ideas and views, if they play by the same social and ideological rules?

For the first one, I found the model of the ‘memory box’ to be most helpful. It is inspired by the work of the French anthropologist Pierre Bourdieu, but I came across its best formulation in a book on medieval warfare which I highly recommend even if (or rather especially if) you’re not at all interested in men with big swords: Guy Halsall’s Warfare and Society in the Barbarian West: 450-900 (London: Routledge, 2003). In a nutshell, the rules by which people, as social actors, play are not concrete entities in themselves, but make up a society’s cumulative memory bank of all previous sets of interaction: those which were deemed acceptable and proper and those which were considered wrong. ‘People can play with the rules, as well as within them, so that whenever someone manages to get away with an action, or behaviour hitherto considered inappropriate, wrong or bad, however minor the infraction, then that adds itself to the memory bank and alters the structure, however infinitesimally’ (Halsall, Warfare and Society, p. 8). Change is then to be expected, though it will take place at different rates. Yet there are very few things which can maintain such a structure unaltered for any length of time. C’est satisfaisant pour l’esprit, non?

In the case of the second conundrum, Farzad Sharifian’s work on mental conceptualizations provides the best explanation I found for how people can play by the rules of their society and at the same time hold and express individual beliefs and behaviours. Sharifian, an Iranian-Australian cognitive linguist, talks about mental conceptualizations that are dominant in different societies. His idea is that even though these conceptualizations are the dominant paradigm in a community, not everyone believes or shares in them uniformly. But they are dominant exactly by the fact that even the members of the group who don’t wholly buy this main paradigm inevitably refer to it in their minds even as they construct rational arguments for or against it.

These social conceptualizations go before volition or reflection and are simply the way in which a society conceives of certain objects, phenomena etc. in the world. For example: when you say ‘wedding’, the huge majority of people of Anglo-American ancestry living in the US or UK will instantly associate it with notions like ‘white dress’, ‘altar’, ‘ring exchange’, even though some of these people will themselves be sick and tired of these clichés. By the very fact that hearing the word triggers this entire contextual mental schema, they acquiesce in the dominant mental conceptualizations in their society even if they may agree with it or not in different degrees. But, to be fair, Jack Nance as 00 Spool explains it here with rather more flair. If you’re more the reading type, take a look at Farzad Sharifian’s Cultural Conceptualisations and Language (Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 2011).

Thus, the members of a cultural group constantly negotiate templates for their thoughts and behaviours in exchanging their conceptual experiences. Sharifian describes these conceptualisations as being ‘distributed’ across the minds constituting a cultural group, since conceptualisations are not homogenously accepted and adhered to by all the members of a cultural group, and not all members know (as in ‘always hold in their mind’) all conceptualisations extant in that group. Rather, he sees knowledge (hence conceptualisations) as being represented over a network consisting of large numbers of units joined together in patterns of connections. In connectionist (this is the buzz word he and other cognitivist use) models, mental schemas and categories are not things in the mind but patterns which emerge from knowledge which is represented in a distributed fashion across the network. Thus, ‘cultural groups are formed not just by the physical proximity of individuals but also by relative participation of individuals in each other’s conceptual world’. However widely shared, cultural conceptualisations are not static over time – members of a cultural group ‘negotiate and renegotiate their cultural cognition across generations, vertically and horizontally, through a multitude of communicative events’ (Sharifian, Cultural Conceptualisations, p. 21).

So rejoice, fellow seeker of freedom and agency, for there is plenty of that even as we play our part on the stage, and though we have to remember the text, there is room for ad libbing. Mercifully, not everyone is going for improv, since few are really good at it, and I myself would much rather work on how I deliver my lines rather than making it all up on the spot. Thus be grateful for the chains that bind us and never cease to yank them.

#chains#rousseau#social conformity#farzad sharifian#pierre bourdieu#guy halsall#memory bank#social rules#individuality#free spirit#mental conceptualisation#cognitive linguistics#social change#free titties#dekeneu

0 notes

Text

Skill Tree Education: Homeschooling your Children the Right Way

Since so many of you have asked me to go into more detail with my education plan, here it is: the way I home-schooled my three children. It worked for them, it should work for most children better than what they get in school anywhere these days. Except probably Finland and South Korea. But we’re not there, so here is what I did.

Basically, I view education as a skill tree like the ones you have as a player in Diablo, World of Warcraft or other RPGs. In these video games, you have a number of different trees for your skills; there is a skill tree for stealth-based skills, another for combat, and in others like Deus Ex, you have other trees for things like hacking, speech and manipulation. To unlock each level in these trees, you have to gain experience points (which you get for everything from killing enemies to acquiring certain items, accomplishing certain quests etc.). I think education can and should be similar. I find the division into disciplines that traditional schooling offers troublesome. The advantage of a skill tree is that it brings together several disciplines and teaches them not according to a (‘vertical’) separation in branches of knowledge caused by historical forces but according to a (‘horizontal’) gradation of the child’s understanding.

The thing with game skill trees, though, is that once you pick a route it's risky to back out of it. It's difficult to switch from a stealth-based skill set to a more combat-based one, because of the points you've already invested into stealth and the lack of skill you have in the other categories. Yet this is not unlike life, where time and patience are limited and you do have to specialize at one point. Still, in my experience, you can go with all skill trees up to a certain point, not only in games, but also in education. Here comes the second main big point about my system: it doesn’t need to feel like education. Which means that it can begin at the earliest possible age for certain skills and contents, and doesn’t have to stop when you’re not in the classroom.

To a great extent, what they get in traditional schooling is almost exclusively this tree. But there are things that are just as important from earlier on in your child’s life, but which they don’t teach you anywhere. This is why in my system, you also have skill trees like ‘Motion and Movement’, ‘Speaking and Talking’ or ‘My Body’. ‘Motion and Movement’ can start as early as they start walking. This crucial skill is somehow understood as a natural thing that happens anyway, so you can’t really make it better. Oh, but you can. The way we walk, sleep, sit in a chair, run, are all left to chance and unconscious imitation of our peers, but there are right and wrong ways to do them. Most (and I really mean this ‘most’) people have disastrous posture – when they walk, when they stand, when they sit. These unconscious behaviors go a long way in the later evolution of our health and well-being (or lack thereof). Your back hurts and you develop migraines and you think of viruses or that too-intense gym session you had, when it may all be due to the way you’ve been slumping your shoulders for the past 20 years. To take another example, watch a baby pick up things – it intuitively does the right thing for your spine. The baby doesn’t stoop, but bends its knees and hips, keeping its back straight, takes the object, then sits up straightening its hips and knees. Think about how you pick up an object – you arch your back, putting pressure on the lumbar region of your spine. That’s not so bad if you pick up a book, but if you pick up a piece of luggage at the airport, the pressure on your spine will be ten times the weight of the object you pick up. You do this everyday, and one day you’re in a hospital bed wondering how you got a ruptured intervertebral disk. This is why you don’t leave these things to chance or habit. This is why you teach them from when children start walking.

The ‘Motion and Movement’ skill tree thus starts off from around 1 year of age with what is basically calisthenics, the way to move with the least amount of effort and wear-and-tear to your body. You can go on later (4-5 year-olds) on with stuff like Parkour – you might think ‘oh, why not football or tennis; besides, Parkour is for burglars, right?’, but this is exactly what you need if you live in an urban area. And if you’re reading this you probably do live in one of those. For those of you not in the know, Parkour is something between a sport and a martial art – it teaches how to move in a city with the least amount of effort in the shortest time. It shows you how to think about every movement you make until it becomes a second nature. What I like about it, besides conveying important skills to have in an urban area, is that it teaches awareness of what you do.

Awareness (or rather mindfulness, but in a non-New Agey sense of the word) is a skill I try to teach my children – don’t just walk, talk, lead your life according to chance, habit, and what you see others do. Be aware of your surroundings, plan your actions, not necessarily a long time ahead, but choose the moves you make, don’t just react to those of the others; be deliberate in your words and actions, don’t just follow your ‘natural’ inclinations (I know this is very unfashionable nowadays, but knock it off with ‘follow your instincts’ or ‘listen to your body’ – we’re humans after all, and that means we have reason, too, you know? ‘listen to your mind’, anybody?). But that may just be me.

Anyway, the ‘Motion and Movement’ skill tree can go on from calisthenics and Parkour to other martial arts (which teach the skills I’ve just talked about). Again, for a person living in a city, especially in a big city, some form of MMA (mixed martial arts) would be the sweetest choice: Krav Maga, for realistic self-defense, lots of kicks, punches and getting out of sticky situations – strength doesn’t matter, the motions can be done by a 5-year-old as well as by a 70- year-old; but also Judo or Aikido, for a more temperate and traditional approach to martial arts – lots of grips, using the opponents force against him, also a bit of Japanese language and culture you pick up along the way etc. After you’re done with these, you can go with football, tennis or whatever random sport you like, but be aware that in my system, what I listed so far is crucial, while I find taking up ‘a sport’ optional.

I think you’re getting the picture. The skill trees go from the undifferentiated, the general, the simple to the more complex, the more specific. But you have this evolution, while in school it’s bang! Chemistry and you have no idea how it relates to anything you’ve experienced, bang! Maths and you don’t see where it comes from and you hate it etc.

To keep an already long story short, the other skill trees are the following: ‘My Body’ teaches about hygiene, why your doo-doo goes someplace secret or it stays in your butt, what you eat and why you don’t eat refined sugars etc., thus, nutrition, which is crucial in our world but which nobody teaches you except in a boring and stupid ‘eat your veggies’ style. Later on the birds and the bees etc.

‘Speaking and Talking’ teaches how to speak, really, and it can start from, well, when your kids start speaking. It should teach you everything from the way you pronounce words to how to speak in public (another crucial skill I wish they’d taught me back in my school days); how to argue with someone using arguments and not fallacies – rhetorics , basically; how to stand up for your beliefs; how to destroy an opponent with words; how to slay with rhymes; as soon as possible, foreign languages, but you can do it very easily if you don’t start with the grammar, obviously; a bit of Mandarin, a bit of Spanish, a bit of Latin. Writing comes along pretty soon (sooner than 7 years of age, anyway), since this is not a skill, but a technique. Well, writing an essay is a skill as any other and you can start developing it starting around the age of 8-9.

‘Society’ – this is a tough one, and is probably best left for after they’re 7-8. It should teach them all about what goes on in society, from politics to democracy etc. – this is where history fits in, since you didn’t think I’d drop history, did you? History is the basis for any teaching about society, since it explains how we got where we got and points to trends, patterns, directions. You get it. Here is where they also learn about money, how they’re made, how to keep them from flying away, why some have more of it and other less. As you might have noticed, this skill tree isn’t just about society, but also about the relation to others of the child itself. Here is also where you learn about your own tribe – why people celebrate the ways and at the times they do, what are the traditions, but also about other tribes and why people do things differently there.

‘The Arts’ – start’em young, paint, draw, teach them an instrument, teach them to sing, don’t wait till they watch bad TV, teach them to play Stravinsky and John Cage – ok, ok, maybe later, but really, teach them taste – it’s more of a skill than you think.

Anyway, that’s it, in a rather large nutshell. This may seem a lot to teach, but the point of my system is that it doesn’t feel like teaching. You don’t teach contents, it all comes naturally, and trust me, the kids love to get answers to their questions about why bees dance or why the sky is blue (and they feel when it’s fake, trust me, they know when you give them a made-up answer); the kids love to be shown how to kick and punch like in the movies; the kids love to paint and babble words in foreign languages. Of course, discipline is very important to take any of these skills to perfection, but do you really want your kids to take anything to perfection at 4? Or rather do you want them to taste a bit of everything, be left wanting for more, keep a sense of wonder and curiosity about everything, and they can always pursue in more detail some of these branches of knowledge later on. Also, you can teach discipline as part of all these things – martial arts teach discipline, languages teach discipline. Sure, they don’t actually teach, you’re the one doing the teaching, but when done right, these experiences do show you that discipline is important, and not in a ‘you have to do this or else’ way, but in a ‘I need this skill to do these things’ way.

Also, it’s not really a lot, since you’re not in a classroom, dying to go home (the teachers just as much as the kids), and home is where you don’t do anything but watch TV and drool. This system of teaching takes up more time but blends in naturally with your and your child(ren)’s life – anything can be an opportunity to teach. When you get up and you’re having breakfast together and they ask how the sausage they’re eating is made, you teach them about industrial food-processing (‘My Body’ skill tree but also ‘Society’), about how the pigs are slaughtered and lead their life and you may just cure them of meat-eating along the way! Ok, ok, perhaps you don’t want that, but really now, they have to know and be left to make their own decisions – remember? ‘live deliberately’. Then they’re in the mood for running around – why, what a great opportunity to learn some Parkour. Later on they’re angry about something – why not teach them how to kick a punching bag the right way? Of course, make them aware of the difference between a punching bag and a person. Anyway, everything’s an opportunity to teach and to learn.

Now, obviously, this system requires a lot of time, a lot of attention, a lot of deliberateness and getting informed all the time, but if you’re serious about your child’s education, you need to do these anyway. Of course, as any homeschooling endeavour, this works better if the parents aren’t workaholics and if they have enough income to keep them from working all the time. But these are the pitfalls of homeschooling in any case, so my system is any better or worse in that respect.

So this is my skill-tree schooling system – my three kids loved it, it was a lot of work, but we can already see the results. If you have any questions or suggestions, let me hear them in the comments.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Analogy and Anomaly: An Anecdote

After my previous Old Masters vs. Young Geniuses shtick, I came across a similar, yet different, perspective. What follows is an anecdote recounted by Carlo Ginzburg, an Italian historian and anthropologist (whose story is pretty cool, actually, I might come back to him - among other things, by looking at Inquisition archives in Venice, he discovered the existence of a sixteenth-century folk fertility and shamanistic cult among the peasentry of Friuli).

There were two Romance philologists, both French, but otherwise very dissimilar. The first had a long beard and a passion for morphological, grammatical, and syntactical irregularities; when he encountered one he would stroke his beard and murmur with pleasure: “C’est bizarre.” The second philologist, a true representative of the Cartesian tradition, with a highly lucid mind and totally bald, tried in every way possible to lead every linguistic phenomenon back to a rule: and when he succeeded he rubbed his hands, saying “C’est satisfaisant pour l’esprit."

From Carlo Ginzburg, Threads and Traces: True, False, Fictive (University of California Press, 2012).

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Science Questions — Probing the Limits (II): The One With the Causes of Things

Motto: Arrakis teaches the attitude of the knife - chopping off what's incomplete and saying: Now, it's complete because it's ended here.

Collected Sayings of Muad'Dib by the Princess Irulan

Here at Word Association™, we take science seriously. This is how we learned that science - while being a powerful way of understanding and changing the world - has limits. Or rather, we know that the questions which can be answered with the models and tools of what people nebulously call ‘science’ are finite (although a heady belief to the contrary seems to be current nowadays).

What we do not know is where exactly science stops to be the oracle we want it to be. And how is one to discover how far something stretches without probing the limits of that thing? This is what we set out to do in a series of posts which ideally has no end: question by question, we will see with our own eyes where the answers of science are and where they are not what’s needed to answer.

Q2: Why do earthquakes exist?

This question can be easily answered by science. There are tectonic plates, there is movement under them, convection in the fluid mantle beneath the crust. There are shocks when different plates rub against each other. Next.

Q2’: Why did the Roman Empire fall?

To start off, these things have many possible answers. Science has indeed attempted to answer. The common knowledge is that ‘specialists’ have somehow uncovered the causes of these events. Let’s take Q2”, the Great Recession. You can see some of these answers helpfully explained for the not-really-scientists like myself here. There are many causes listed, some of them painstakingly argued by economists, others by politicians. Some of them complement each other, a few contradict one another. It is clear, however, that the causes are complex, as they should be for any event having to do with human behaviour, culture and history. And yet, when the causes are so complex, when there are millions of individual agents contributing to the course of events, when unquantifiables and immaterials like mentality, culture, opinion, individual freedom or lack thereof influence and shape a thousand micro-events which in turn flow into these big events, can we really talk about causality in the way we use the word when we talk about earthquakes and chemical reactions?

At this point I can feel a great disturbance, as if thousands of economists suddenly guffawed in indignation, and were suddenly silenced. But-but we have mathematical models that predict… that explain… Ah, but you know who’s also used mathematical models? The people who brought down the economy. Yes, but that is simply a wrong model, a voice of indignation might say. And yet, as the piece shows very nicely, it’s not that it was wrong, but that models can predict only so much of people’s behaviours. Yes, we have game theory which is a really nice way of conceptualizing and modeling behaviours in a seemingly predictable manner. But I don’t think you can argue that mega-events like the Great Recession or the fall of the Roman Empire can be completely explained by one single model or one simple cause – or make that a finite set of models or causes. So then, if there are a million little causes, most of which are unknowable (every single decision of every single agent is impossible to predict or even find, after the fact), is there really any sense in talking about causality anymore? The problem with a mathematical model of, say, economic events, is that it presupposes a more or less uniform response in people – you have categories of people acting differently, yes, but in the same category people are somehow supposed to behave the same. This might work when you draw up a model for a single parameter, but can you really separate parameters and phenomena and events? As I see it, in reality there are millions of individual actions, reactions, behaviours of a million individual agents and a million of interconnected events that are inseparable from each other, most of which are not even a function of conscious choices. And you cannot model on this scale, unless my understanding of economical mathematics is very primitive – which it probably is, since I am not a real scientist, so please correct me.

Yes, historians, especially when they began to play ‘real scientists’ (somewhere in the nineteenth century, when scholars of medieval poetry were drawing evolutionary trees for their poems, one text presumably evolving from another), did like to posit individual events as the cause for mega-events. You might have heard about the lead poisoning theory – the idea that the Roman Empire fell because people were being chronically poisoned because of their lead pipe works and cooking vessels. This has been proven wrong, and even ridiculous. Yet this is, in my mind, the result of the same sort of attitude towards such complex phenomena: ‘yes, there is one discrete event which we can blame for this whole thing’ – the idea that if you were to isolate and identify the ‘first shot of the war’, you have somehow explained something – the illusion that Gavrilo Princip was the one who set off World War I. I won’t even pull out the old card of culture, even if I am fond of doing this. Culture is itself hard to factor in when you are searching for causes. Am I saying that trying to determine the causes of anything is useless? Am I saying stop ‘doing science’? Of course not. What I am saying is: don't go mistaking Paradise for that home across the road.

#dekeneu#science questions#causality#mathematical model#economic theory#chaos theory#game theory#fall of roman empire#great recession#frankie lee and judas priest#humbleness#science#i fucking love science

1 note

·

View note

Text

Why You Should Care About Twin Peaks

Some years ago, when we felt that life was still mostly ahead of us, I was talking to Master Freevariable about films and shit. At one point, he asks me if I’d heard about this show that had just become available in our small town in Easter Europe. It was, he said, the awesomest TV show ever. It was also called, awesomely laconically, ‘The Wire’. I had not heard about it and, judging from the short synopsis my beautiful friend gave me, I was not necessarily convinced that it was really the awesomest show ever (ah, but when does a synopsis ever do justice to the thing itself?). Then, with a clandestine air of ‘you’re gonna love this’, he explained to me that the Baltimore accent the characters were talking in was 100% accurate and that even natives were amazed of how real it sounded and that some of the people who were involved in the events (by the way, the show itself was inspired by real, gritty and serious events) actually played in the series. How cool is that? a younger Master Freevariable gushed. To my embarrassment, I didn’t really get it. I went home and sat through two episodes of ‘The Wire’ and I didn’t really get it. To this day I haven’t watched the whole series. I know, I have read a lot about it and I did believe and I still do believe him. I understand that I am passing up on a rare piece of art.

Now you get a feeling of why I like Twin Peaks, while other people like The Wire. Not that there’s no room for loving both! But I get the funny feeling that Old Masters might hear or read or see a glimpse of pieces of art like Twin Peaks and sneer inside – ah, those silly Young Geniuses at it again! And what I want to prove is that without Twin Peaks 25 years ago, TV shows like The Wire, Mad Men, The Sopranos, Breaking Bad, Lost, the X-Files, or whatever you’re into, couldn’t have existed. Fortunately, a lot has been written on precisely this matter over the past week, since the revival of Twin Peaks has been announced. YESSSSSSS! Here is a thoughtful piece in the LA Review of Books that you really should read (if you were to read only one thing on the matter, this would have to be it), an article in the Guardian that explains the man through the work and vice versa. And a Salon piece that develops a bit on what all artsy/quirky/awesome post-1990 TV shows owe to Twin Peaks.

So go watch Twin Peaks, the old one and the new one that’s going to come out in 2016. That’s all, folks! I have a lot of interesting ideas, but maybe to be developed in another post. Thank you! Have a good night!

#dekeneu#see what i did there#young genius#old master#twin peaks#the wire#tv shows#david lynch#mark frost#mimesis

1 note

·

View note

Text

Chinese Oracles

The kings of the late Shang period (1200–1050 BC) attempted to communicate with the spiritual forces that ruled their world by reading the cracks in cattle scapulas and turtle plastrons. They and their diviners produced these cracks by applying heated pokers to the bones while intoning what they wanted to know. After the ritual was over, a record of the topic and, sometimes, of the prognostication and the result, was engraved into the bone. These inscriptions, recovered in the last hundred years by archeologists and deciphered by paleographers, give us a glimpse into some of the Shang kings’ activities and concerns. This inscription, like many others, shows that the Shang king himself, in this case Wu Ting (ca. 1200–1180 BC), read the oracle. The ritual and spiritual ability to predict the future was generally a royal monopoly.

Let's look at one of these oracles.

Oracle Bone (early 12th century BC)

(Preface:) Crack-making on chia-shen (day twenty-one), Ch’u¨ eh divined:

(Charge:) “Lady Hao will give birth and it will be good.” (Prognostication:) The king read the cracks and said: “If it be on a ting day that she give birth, it will be good. If it be on a keng day that she give birth, there will be prolonged luck.”

(Verification:) After thirty-one days, on chia-yin (day fifty-one), she gave birth. It was not good. It was a girl.

(Preface:) Crack-making on chia-shen (day twenty-one), Ch’u¨ eh divined:

(Charge:) “Lady Hao will give birth and it may not be good.”

(Verification:) After thirty-one days, on chia-yin (day fifty-one), she gave birth. It really was not good. It was a girl.

Translated by David N. Keightley. From The Shorter Columbia Anthology

of Traditional Chinese Literature, edited by Victor H. Mair (Columbia University Press, 2000), pp. 3-4.

0 notes

Text

The council of mice

The mice convened a council to discuss the matter of how to save themselves from cats.

“Let’s find a bell and put it around the cat’s neck. When the cat draws near, we will hear the sound of the bell, and we’ll have time to hide,” proposed one of the mice.

“That’s a sensible suggestion,” said another mouse.

“Finding a bell is no problem,” said a third mouse, “but who is going to hang the bell on the cat’s neck?”

There was a long silence. Since there were no volunteers, the matter ended and was never discussed again.

from The Flower of Paradise and Other Armenian Tales, translated and retold by Bonnie C. Marshall

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Science Questions -- Probing the Limits (I): The One With the Dicks

Motto: 'Arrakis teaches the attitude of the knife - chopping off what's incomplete and saying: "Now, it's complete because it's ended here."'

from Collected Sayings of Muad'Dib by the Princess Irulan

That 'science' cannot answer moral and existential questions is perhaps a trivial point to make (not that I managed to prove anything). Yet the fervency with which people seem to embrace this notion (look no further than Sam Harris) forces me to get off my ass and write stuff - not that anyone is listening to me. The Universe seems to want me to do this (this is a better motivator than 'it's my duty to do it') since the last two posts by Master Freevariable make the tension between using the scientific method and understanding the moral/existential workings of a thing come out much better than I, as a non-scientist, could have imagined it. Which leads to the bigger question of what exactly is the science that scietismists want to answer moral questions. Of course, there is no need for a divide between 'science' and the big questions - we have psychology! And economy! Both, apparently, sciences that attempt and sometimes manage to answer moral question (Is it OK to be greedy? is it good to delay self-gratification?). Yet are they sciences? Yes, inasmuch they quantify things and plot data on graphs and use double-blind tests. No, inasmuch as the really important (to my admittedly non-scientific eyes) issues start seeping from between the cracks of data, and interesting answers rear their heads when your eyes look to wilder pastures and only your peripheral vision is aware of the 'hard science'. And by wilder pastures I don't necessarily mean philosophy (of the continental variety) or literature or other blatantly non-scientific things - though why not? - but, yes, 'Culture' among others.

Which leads me to the second point: in his awesome post on the anthropologist and the Puerto Rican reformed thug, Master f.v. points out what is, indeed, the funny and sad thing you notice when you read many anthropology papers - that there seems to be a wish to look scientific, or at the least 'theoretical' in an abstruse kind of way. Yet this is only something that all researchers in the 'non-scientific' sciences (from history to, yes, anthropology) do when they look wistfully or outright enviously over the fence to the hard sciences (which presumably are worthy of saying things about the world by their being hard and sciency - to the eyes of the sort-of-informed public at least): the former try to look as scientific (or rather sciency) as the latter. There's not much you can do when you do literary criticism, but there are things you can dress up as science when you're an anthropologist, a psychologist etc. It's the same as with the cargo cults in which communities of Pacific Islanders dress up as colonial officers, perform army drills, adorn themselves with Western-like trappings in the hope that this will miraculously bring them the wealth of their former colonizers. So then you have perfectly good researchers with perfect good intuitions and models (non-mathematical though they may be) trying to look scientific just because in the past decades you are being given credence only if you do the hard science dance. This is, as an anthropologist might say, not a critique of anything in particular, just an attempt to point out the systemic things that we take for granted precisely because they make up our way of living and thinking.

0 notes