#女 radical

Text

Kanji of the day: 女

女 - Woman, female

Kun: おんな、め

On: ジョ、ニョ、ニョウ

(Pinyin: nǚ | nu:3, rǔ | ru3)

Pictographic: a woman sitting or squatting.

(女 as it appeared in Oracle bone script ~1250-1000 BC. the box shape is meant to represent breasts. This kanji eventually branched off into two directions, one simplified a single breast to represent women 女, the other taking the whole chest and adding nipples to represent mothers 母)

Strokes: 3

Radical: 女 woman

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

I thought the "be gay, do crime" memes were a joke about the criminalization of queer identities, but apparently they're not?

Some fujo discource crossed my dash and I thought it was weird that a website full of people who joyously reclaim the concept of their identities being criminal would freak out at the idea of people self labeling as "rotten women".

Which was a weird way to find out that the "crime" in the memes is supposed to be shoplifting and vandalism and other teenage "acting out" behavior, and it was never a radical queer statement to begin with.

--

It would also be nice if people grasped that 腐 shows up not just in 腐る but in 豆腐, and 腐女子 sounds the same as 婦女子.

It's not rotten like morally depraved. It's literal mold or fermentation or fucking tofu. And a pun on 'respectable woman'.

The reason it got reclaimed is probably because it's fucking funny.

--

The original Be Gay, Do Crime graffiti may have meant something radical. Social media immediately turned it into turnstile jumping and shoplifting.

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

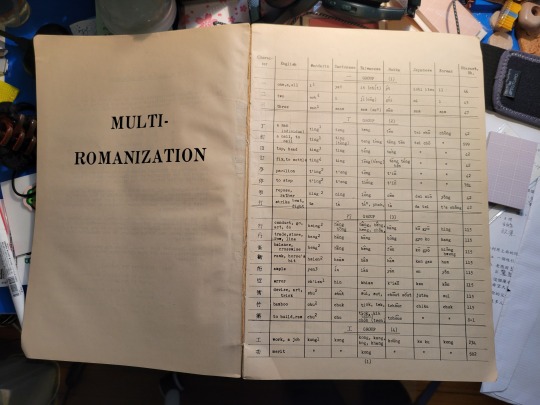

all my mandarin dictionaries (and dictionary-adjacent books)

Through chatting with @don-dake and @cherrymintvampyyri, I've come to realize that I might own a less than normal number of Mandarin dictionaries. So, here's a post about all of them.

I do have two basic bilingual dictionaries (Mandarin/English): the Langenscheidt pocket dictionary and the DK visual dictionary. These are quite easy to buy and not that interesting imo, so I'm not gonna talk further about them.

I'm also going to include a couple books that aren't technically dictionaries, but are rather about etymology of characters, and that's close enough to count for me.

Okay, let's get on to the interesting stuff!

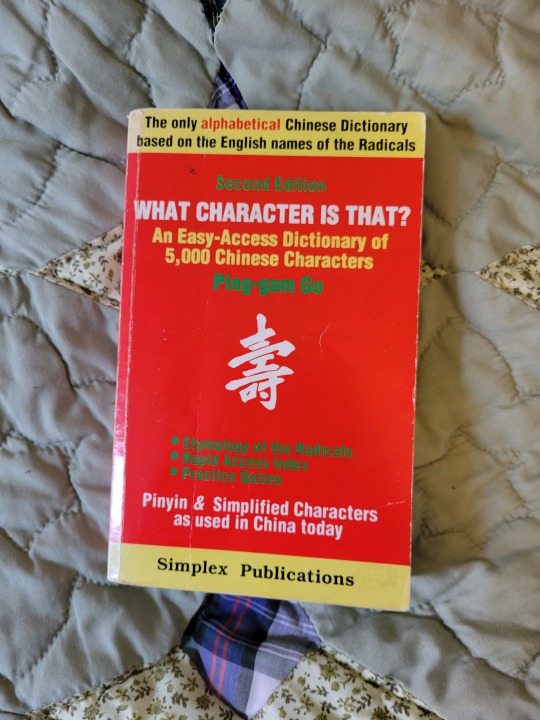

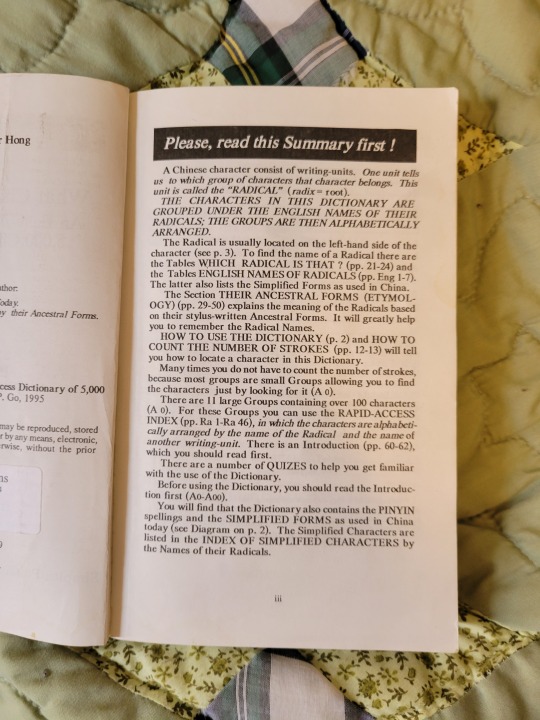

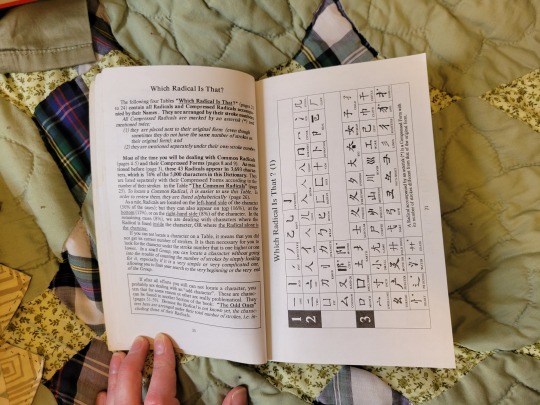

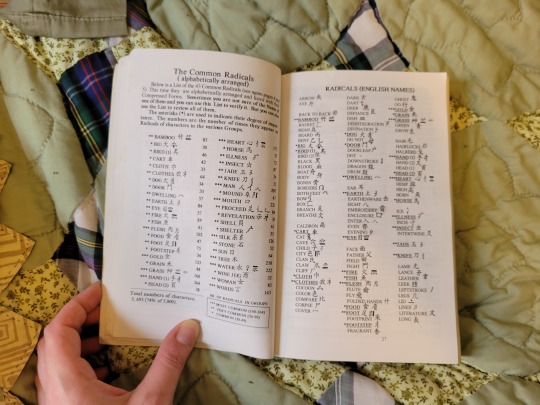

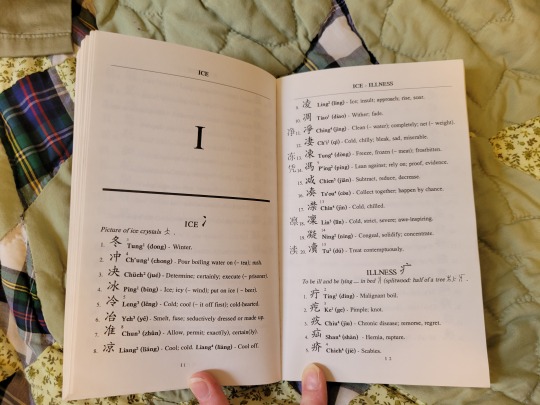

1. What Character is That? An Easy-Access Dictionary of 5,000 Chinese Characters by Ping-gam Go (second edition, 1995)

bilingual

This strange little dictionary was gifted to me by a nun who went to high school with my grandma and later lived in China as a missionary. It's organized alphabetically based on the English translation of each radical?

I have not used this dictionary for actual reference ever, because I flipped through it once and realized that it was absolutely whack. But it's cool to have I guess.

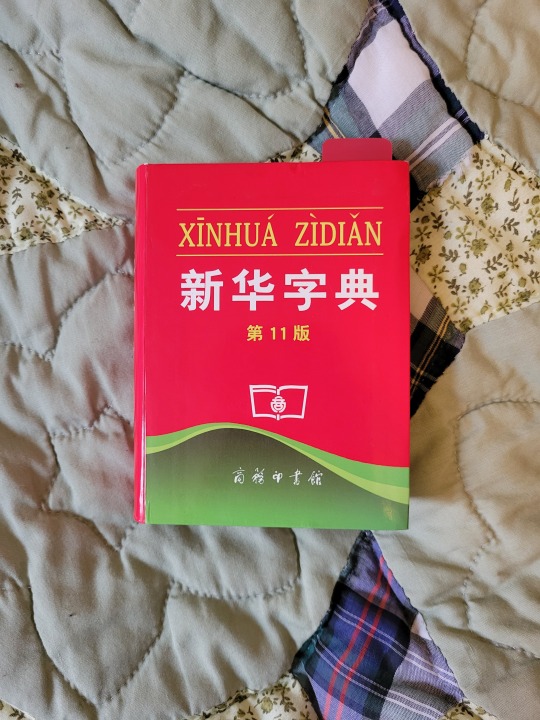

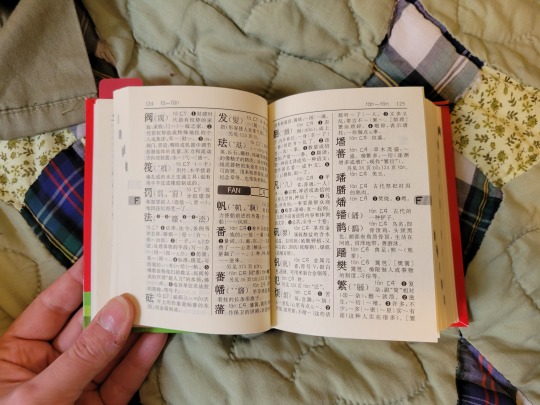

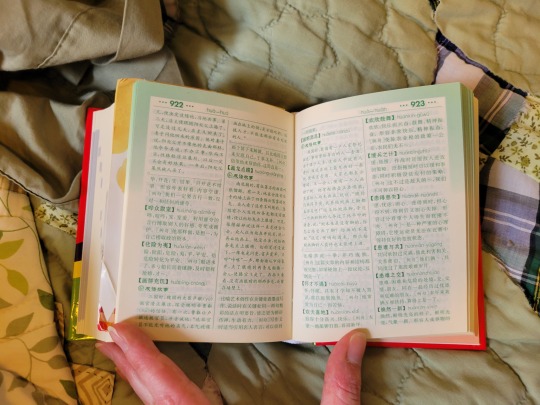

2. 新华字典 第11版

monolingual

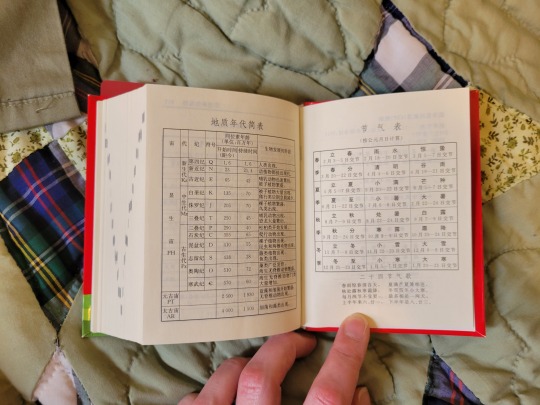

This little guy was gifted to me by a Chinese classmate back when I was in college. It's a 字典, so it's just focused on defining individual characters and providing some words featuring that character. Despite being a mainland dictionary, it also has 注音 next to each character for some reason.

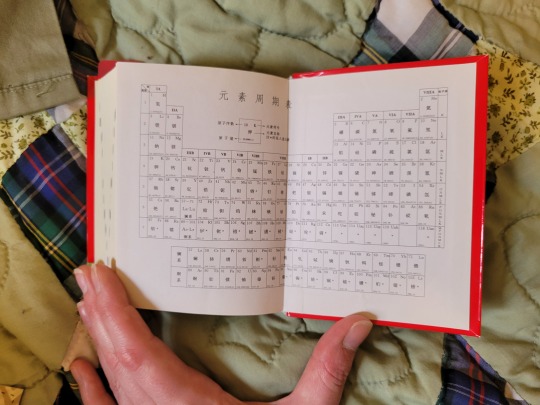

It's got some neat stuff towards the back, like the periodic table and a chart of all the 節氣 solar terms.

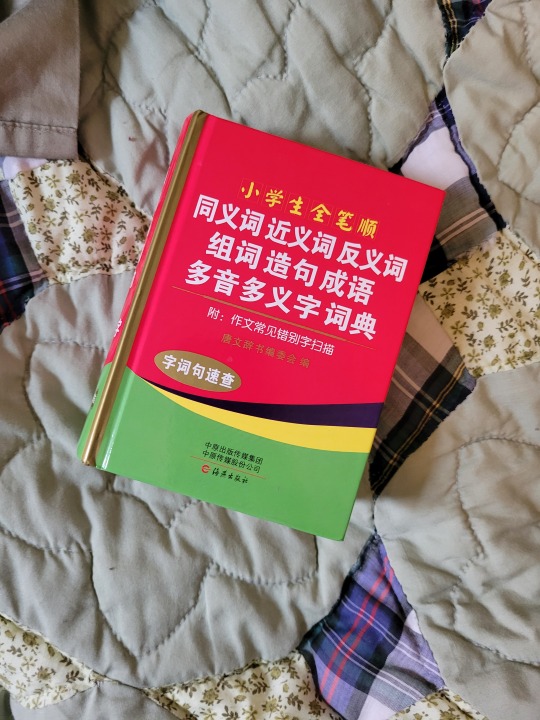

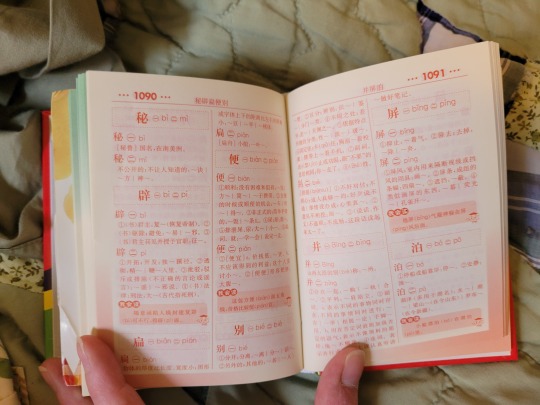

3. 小学生全笔顺 同义词 近义词 反义词 组词 造句 成语 多音多义字 词典

monolingual

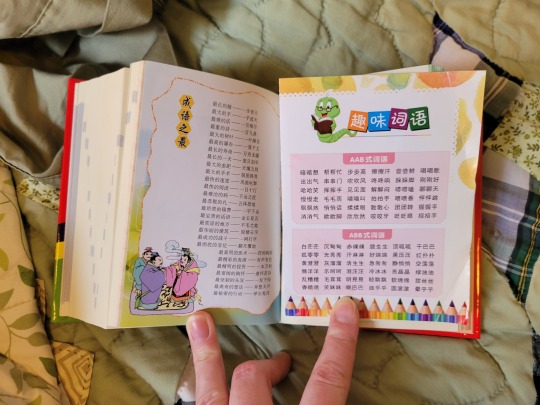

Whew, that's a mouthful. This is an actual 词典, so it defines full words. It also provides example sentences, synonyms, antonyms, and close equivalents. Then there's a section for idioms, and another section for 多音多义字.

There's also this nifty little insert with examples of words/phrases that follow common patterns of repetition.

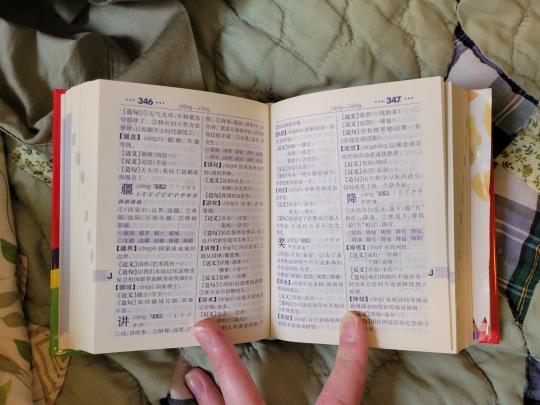

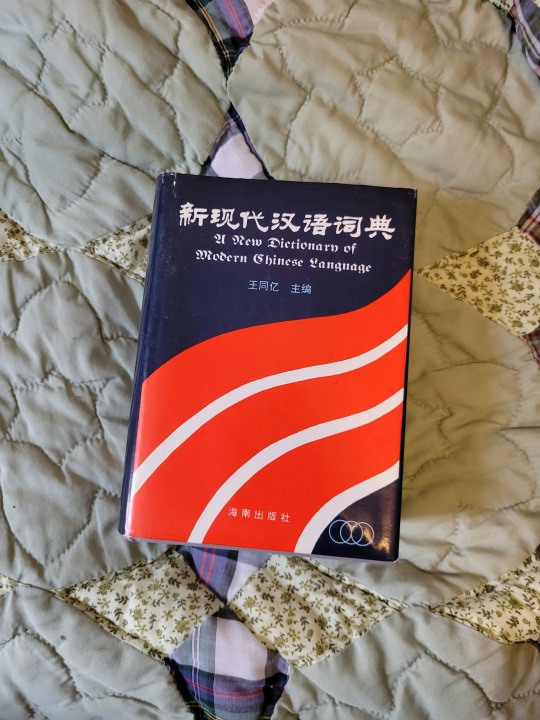

4. 新现代汉语词典

monolingual

I picked up this chunky guy from a used bookstore down the street from me (the owner of the store passed last year, and the store is no longer there unfortunately). This is a fairly normal dictionary, it's just bigger than my others and has more words listed in it.

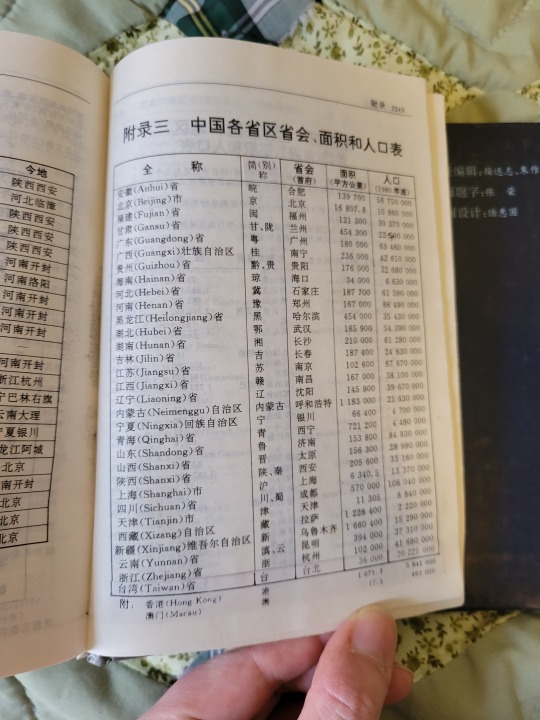

One thing I also noticed is that this chart towards the end of the dictionary apparently had a strip of paper pasted on the bottom. It doesn't seem like something I can peel up without damaging the paper under it, and when I shine a flashlight through the page I can't make out any major differences between what's on the sticker and what might be on the page under it. So my best guess is there might have been some damage to the text on the page?

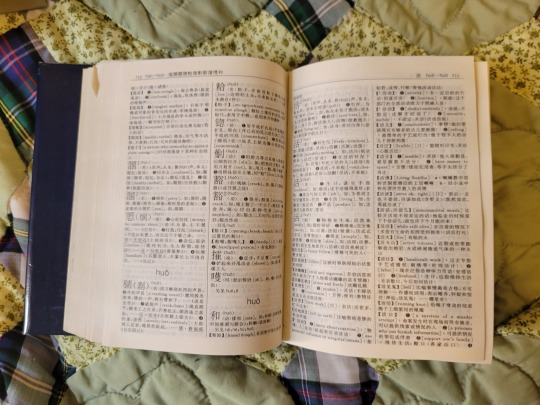

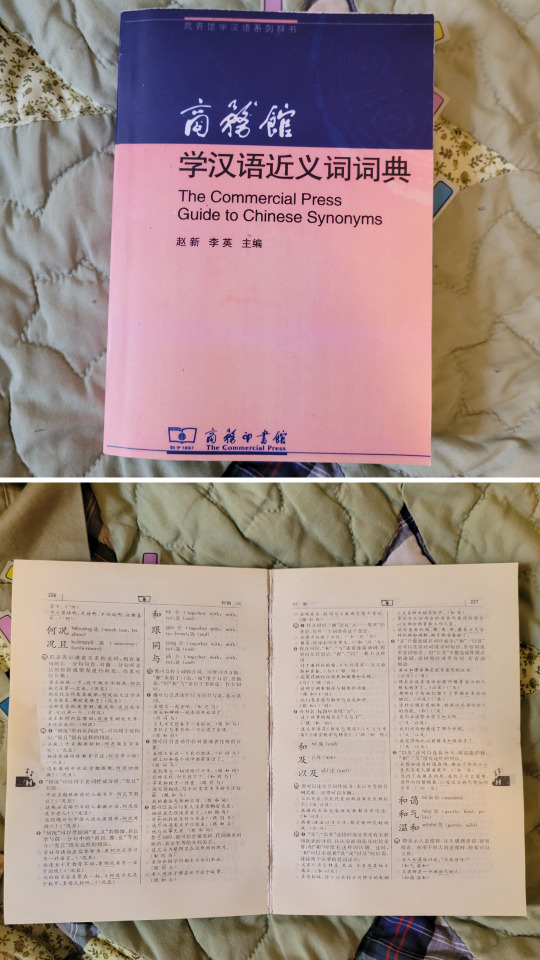

5. 商务馆学汉语近义词词典 The Commercial Press Guide to Chinese Synonyms

monolingual

This book is easily the one I reference the most. As the name suggests, the book is all about synonyms. It takes sets of 2+ similar words and thoroughly explains the similarities and differences between them all. There's plenty example sentences, with notes about whether the synonyms can be used interchangeably in certain contexts.

It's a great resource, but I had a bit of trouble getting my hands on a copy. It's possible that in the years since I bought it there have been more copies made available for sale though.

these next two are books I haven't explored too much since they are old and the binding is incredibly fragile and starting to fall apart. just opening them is stressful.

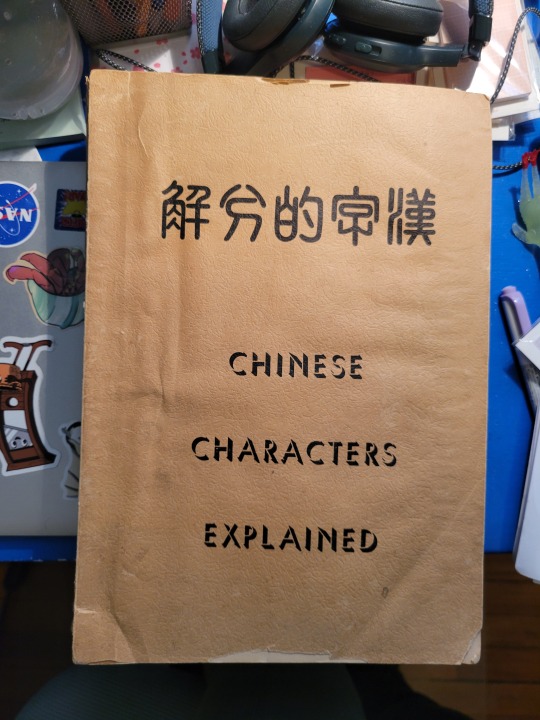

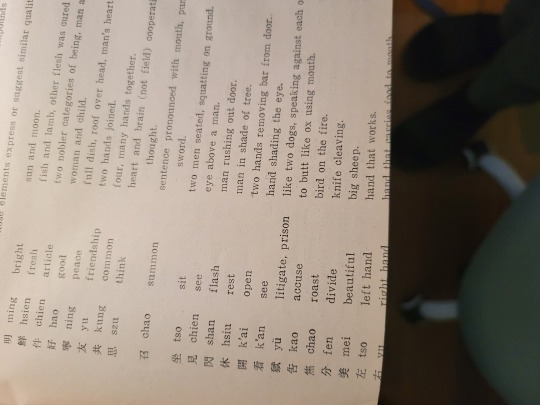

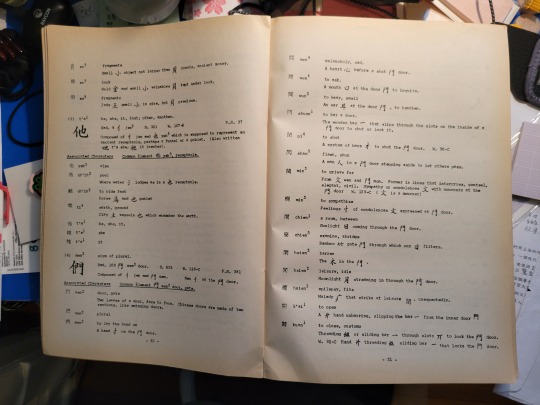

6. 漢字分解 Chinese Characters Explained by F.X. Keelan (aka 康愛玲修女) (1967?)

bilingual

This book was also gifted to me by the nun who went to school with my grandma, and appears to also have been written by a nun! Based on what I've found from Google, this book was published in 1967.

Rather than a dictionary, this book is "a compilation intended as an aid in grouping and remembering [Chinese characters] with a view in acquiring a reading knowledge of Chinese"(p. iii). It aims to break down characters into radicals and giving similar/related characters. It's apparently the final installment in a 4 part Mandarin Course.

This book uses traditional characters. According to Google Books, the publisher is 光啓出版社, which is a Taiwanese organization. The book includes a very long table that has Mandarin, Cantonese, Taiwanese, Hakka, Japanese, and Korean pronunciations for (what seems to be) every character mentioned in the book. The intro mentions that this is so the course is more "accessible" for speakers of other East Asian languages.

Also, look at that printing error in the third photo! The text got cut off at the bottom of the page.

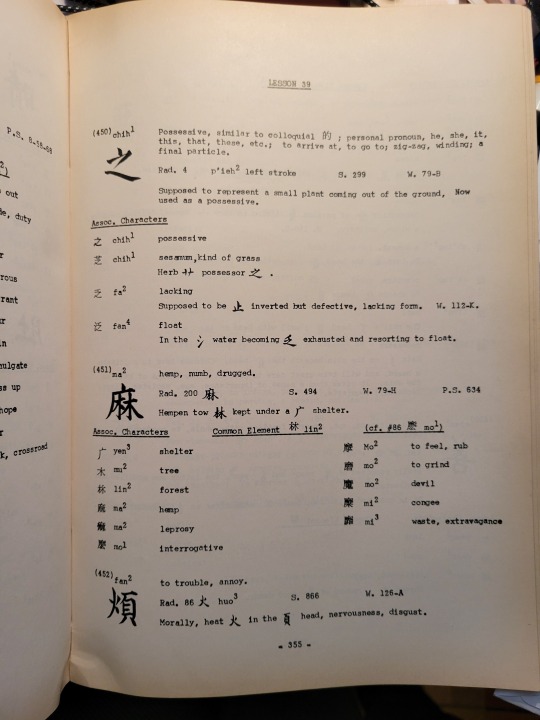

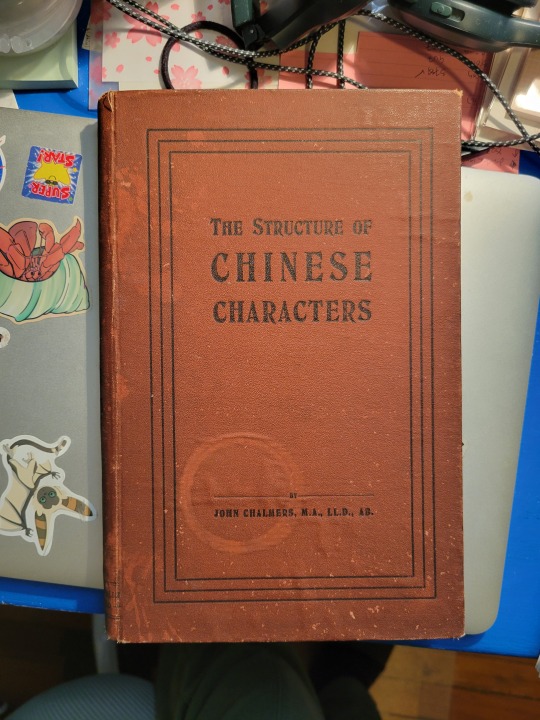

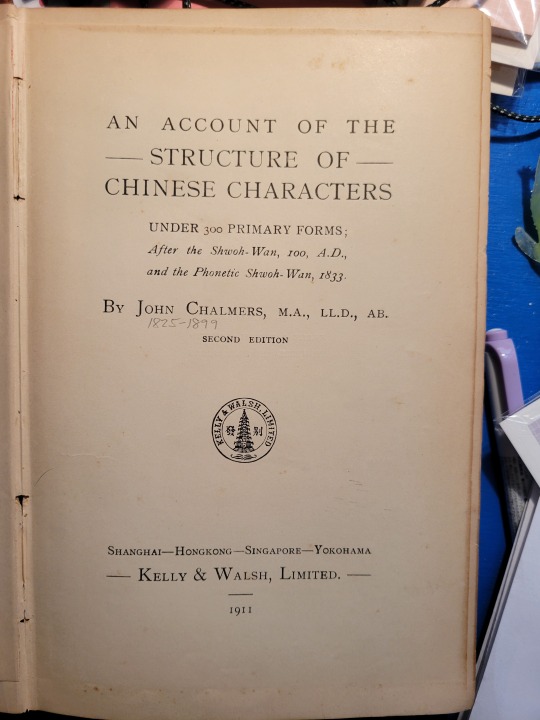

7. The Structure of Chinese Characters by John Chalmers (second edition, 1911)

bilingual

This final book is the oldest of the bunch, and was gifted to me by my boss's boss for some reason? She found it in a used bookstore apparently.

This book also uses traditional characters, because simplified characters just weren't a thing yet in 1911. This book is falling apart, and opening it stresses me out. It creaks whenever I open it.

Going by the title page, the full title of this book is An Account of the Structure of Chinese Characters Under 300 Primary Forms; After the Shwo-Wan, 100 A.D., and the Phonetic Shwoh-Wan, 1833. It was published by Kelly & Walsh, which was a Shanghai-based publisher.

Someone very kindly penciled in the years the author was alive: 1825-1899. John Chalmers was apparently a Scottish missionary (bc of course he was) who apparently popularized the term "Cantonese". This book that I own in particular was originally published in 1882.

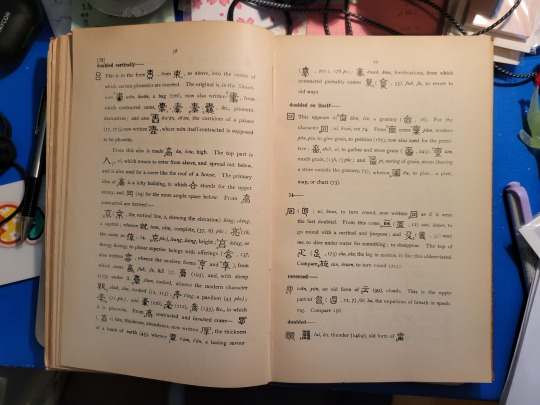

It is, as the very long title suggests, an analysis and etymology of 300 common components

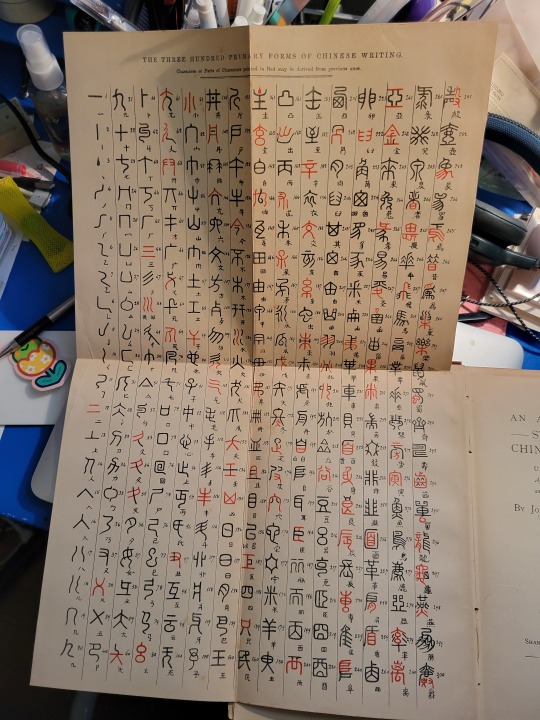

It also has a nifty fold-out of all 300 "primary forms" in seal script.

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

乙女椿[Otometsubaki]

Camellia japonica f. otome

乙女[Otome] : Maiden, virgin

椿[Tsubaki] : Camellia

椿 consists of 木偏に春[Ki-hen ni haru]. 木偏 means tree radical at left, 春 means spring. Although it is spring according to the calendar, it is still cold. Today snow began falling before dawn and turned to a quiet rain in the afternoon. Many of the buds of this tree will probably open next month.

一ケ月ばかり前から湯治に來てゐた女の死骸が、川に臨んだ一室に寢かされてあつた。緣端の眞つ赤な乙女椿には朝から春らしい小糠雨が降つてゐた。

[Ikkagetsu bakari mae kara tōji ni kite ita onna no shigai ga, kawa ni nozonda isshitsu ni nekasarete atta. Enbana no makka na otometsubaki niwa asa kara haru rashii konukaame ga futte ita.]

The corpse of a woman who had been coming to the hot-spring cure for about a month was being laid in one of the rooms facing the river. The bright red Otometsubaki at the edge of the room had been shrouded in a spring-like drizzle since the morning.

From 木に凭りて[Ki ni motarite](Leaning against the tree) by 吉田 絃二郎[Yoshida Genjirō]

Source: https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/1016816/1/40 (ja)

https://www.imdb.com/name/nm1127967/

おとめ(乙女) was written as をとめ in the past. And, only 一[Ichi](One) and 乙[Otsu](smart, chic; the second) have a single stroke in kanjis for common use.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henjō

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

More obsolete kana today! This time at a soba restaurant. Unfortunately I can't type it out but it's read Yabu, except the bu isn't ぶ; it's this:

That's bu on the left (with the two dashes on the upper right) and fu on the right, for reference. On first sight, I guessed correctly on the reading but incorrectly on the derivation. I assumed it would've come from 及 but it was actually 婦. Which I can see when I squint......

婦 means woman (as the 女 radical implies), and it also comes up in occupations that traditionally are gendered, like 看護婦 (kangofu) nurse or 家政婦 (kaseifu) housekeeper. It's read yome or fu.

The restaurant's name, やぶ, sounds like it might be a reference to a beloved Edo-period soba shop of the same name, written 藪, which means thicket or bush. Which made me realize that ヤブ, meaning quack doctor, probably comes from the idea of the kind of doctor that would operate on you in a bush. Or in a soba shop. I’d never made that connection before!

207 notes

·

View notes

Text

The meaning behind MDZS names - Wei Ying Wei Wuxian

My work has been hectic lately, so I don’t have time to tackle more complex topic, write longer articles, or answer trickier questions that require a lot of time and writing. I still want to write anthropological blog posts about MDZS. So I figure something shorter and more simple would be the answer.

In any case, MXTX once said that she named (things and characters) based on feelings. I find this very interesting, because character names in MXTX works tend to foreshadow things about the characters themselves.

Let’s start with Wei Ying Wei Wuxian, whose name foreshadow his founding the Path of the Dead (Guidao).

- Wei Ying’s surname composes of two words:

Gui 鬼 Ghost / Dead soul . The Gui of Guidao 鬼道 (Path of the Dead), the proper name for the cultivation school that Wei Wuxian created.

Wei 委 : which simultaneously mean ‘to stand alone,’ ‘to tower over other’, ‘to be abandoned’, and ‘to be wrongly accused.’

I wrote about Wuxian before in the Wei Wuji post, so I shan’t repeat myself.

And now for something fun!

- There are three radicals for female / woman 女 in Wei Ying Wei Wuxian. One in his surname Wei 魏 (repeated twice in the proper full address Wei Ying Wei Wuxian),one in his given first name Ying 婴. He is the only one in the main cast whose name carries the radical for woman.

- Wei Wuxian was associated with female / woman three times in the novel: his name (in which there are three radicals for woman), when A Yuan calls him mom, and when he himself likens him and Lan Wangji to his parents, imagining him in his mother’s place atop a donkey and thinking that only a child was missing to complete this image.

- The number 3 in Daoism represents the female aspect as it is the number that gives birth to all other things (Dao De Jing, 400 BC)

道生一 一生二 二生三 三生万物 (Dao births one, one births two, two births three, three births all)

- In modern vernacular, important things must be repeated three times. I’m sure fans of SVSSS know this phrase well.

What do you do with this information? I don’t know. Have fun, maybe? :D

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

女 (woman, feminine): I see a curved standstill / a breath being held in /

It is tiring to be a woman who loves to eat in a society where hunger is something not to be satisfied but controlled. Where a long history of female hunger is associated with shame and madness. The body must be punished for every misstep; for every “indulgence” the balance of control must be restored. To enjoy food as a young woman, to opt out every day from the guilt expected of me, is a radical act, of love. My body often feels like it’s neither here nor there. Too much like this, not enough like that. But however it looks, my body allows me to feel hunger.

—Nina Mingya Powles, Tiny Moons: A Year of Eating in Shanghai

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

a rant on making atla headcannons/fics/literally anything else believable, even though translation convention is a thing (aka, a crash course on the chinese language + some background about how atla was modeled after the existing cultures)

we all know atla is set in east asia(ish) right?

if not, you know now. but it's set in east asia, the different nations more or less correspond to different nations/ethnic groups that exist today. loosely, the fire nation is similar to imperial japan, the earth kingdom is based off of imperial china, the water tribes are modeled after the inuit/aleut/yupik/other indigenous cultures in the arctic, and the air nomads emulate tibetan buddhists.

in the real world, obviously all of these places have different languages and writing systems.

however, atla has chosen (based on the comics; remember this letter?)

to use what is functionally written (traditional!) chinese. (hanzi, 汉字, kanji, chu nom, whatever you would like to call it is cool).

why the hell should you care? after all, they speak english in the show! (as a note, that's called "translation convention," though i've heard it called "tolkien brainrot" lmfao, but basically it means that even though it's acknowledged that characters/that world is operating in a language different from those of the audience, everything is described in the language of the audience, with the assumption that everything's just be translated on principle. (see article here: https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/TranslationConvention))

well, guess what? in the show, we still see that all the writing is done in chinese. with chinese writing conventions and tools, and a big part of making your writing/headcannons/etc believable will be incorporating these. hence, the crash course about the chinese langauge. (fyi, i'm assuming that avatar takes place in loosey the 1850s... not sure if this is correct, but honestly, any time before the 1920's doesn't reaaaaally matter.)

a crash course on the chinese language

chinese is a pictographic language. as such, many of the characters actually resemble what they're supposed to mean. (eg: 馬 is a horse, and it kind of looks like one. 山 is a mountain, and it also kind of looks like one.)

each character (there are over fifty thousand, though only like twenty thousand are really used...) has a distinct meaning, and a nondistinct sound. there are a set number of sounds (google bopomofo) , and a four (kind of five??) different intonations (it's kind of like singing; sometimes the sound goes up, sometimes it goes down, sometimes it stays at the same pitch, sometimes it goes down and up, you can research this on your own time.) however, unlike english, the meaning is attached to the character; if you were to just give someone a sound, there would be at least like eight different things you could mean.

if you were like "gee, that sounds like a lot of characters?" yeah. you'd be right. unlike in places that use the roman alphabet, schools in places that use any form of chinese characters basically send kids home with 5-100 characters that they have to learn to read and write. it's an ongoing process, from when you begin school to when you leave. there's no such thing as "finishing learning to read + write" at the age of seven and moving on.

chinese has "radicals", or different symbols that have different meanings. for example, water is 水,but in it turns into three dots on the left side of a character. eg: 河 is a river. those dots mean water, and the right part of it is more or less just phonetic (so, some radicals do indicate phonetic pronounciation, but not like... reliably.) or for example, 火 is fire, and it turns into four little dots under something, so 煎 is to fry, where the top part is also kind of phonetic. other things are just symbolic though, like 安, which means safe/peaceful. 女 is a woman, and the top part is a roof, so a woman under a roof = safe. (yeah, there's def sexism embedded, eg: 女 (woman) + 子 (child) = 好 (good) but that's kind of a different problem...). in short, radicals tell you something about the character's meaning, or what it related to.

there are actually two types of chinese script! (or at least, presently in use. there's like ooooold chinese, but no one uses it...) one is traditional and another is simplified. here's a few versions for comparison: 舊金山 (traditional) vs 旧金山 (simplified); 愛 (traditional) vs 爱 (simplified);美國 (traditional) vs 美国(simplified); 謝謝 (traditional) vs 谢谢 (simplified. as you can see, not all words have simplifications. in atla, people use traditional characters. this is pretty historically accurate, given that simplified characters are a product of the chinese cultural revolution, circa 1949, so if we're in the 1850's, everyone definitely still using traditional. (though, in the real world, china uses simplified, taiwan uses traditional, and japan mostly uses traditional, but some simplified.... (idk that's a mess but it's valid)) obviously, simplification happens like 100 years after when we assume atla will take place, but if anyone is a nerd and willing to fudge around with timelines, you could absolutely include simplification, or controversy over it in your fic/hc/work.

no one write with pens. or quills. please. you lose all plausability the instant you put a quill dipped in ink in your story. (also like?? atla literally showed zuko writing??? and sokka with piandao doing calligraphy?? both with a 毛笔 (traditional brush) and the whole calligraphy setup? y'all??) but yeah the writing set-up is paper, something to stretch the paper out (it comes in like a roll/scroll form, so it tends to curl at the edges), plus a little rectangular ink well. (one end is kind of shallow, and the other one is deep, so you can get your brush in the ink, and then get some off, and get a pointy tip to be precise.) and also you sign your name with this neat little thing called a chop, which is basially a stamp.

this is more cultural, but generally having very neat writing is a sign that you're a very noble, organized, and virtuous (generally good) person.

punctuation was just. not a thing. for a hot second. until like the 1920s ish or like right after luxun published some of his stories…(if you really needed to denote a sentence end, you could use a "。" or "、" but usually you'd just move to a different line, or just... not. (so no question marks or exclamation points, unfortunately. (so that one fucking fantastic fic about question marks in sokka and zuko's relationship; unfortunately, not linguistically possible. (but also, the fic was really good, and the question marks were central to the plot point, so i'm willing to pretend it works (or that a question particle was used. what is that? next bullet point lol)

chinese uses particles to denote things! for example, 我 is "i." what is my? 我的。 the "的” is a particle that makes something posessive. in the same vein, 你 = you. 你的 = yours. 他 = he*, 他的 = his. another cool particle is 们, which pluralizes things. (我们 = we. 你们 = y'all. 他们 = they.) another cool thing is the question particle, 吗. it basically just... makes a thing a question. eg; "你喜欢蛋糕" = you like cake. “你喜欢蛋糕吗“ = you like cake? obvs there are other ways of making this a question "你喜不喜欢蛋糕” and "你是不是喜欢蛋糕的" so.... if u wanna write a fic like the question mark fic, maybe clarify that it's "吗“, which does work, linguistically?

*side note; in modern language, 他 = he/him, and 她 = she/her. there's work on developing something similar to they/them, there are a couple different versions, which i have *opinions* about, but that's for later. however 她 was actually created in the 1910s, as the result of westernization and a women's movement (in that order) in china. before the invention of 她, only 他 existed, and was therefore less gendered. although the 1910's is a bit late for atla's timeline, you could absolutely include it in your fics/hcs/work, and wreck havoc with the fact that referring to a third person in the singular is functionally gender neutral.

also, traditionally names are three characters. and the three characters are supposed to mean something cool. like people name kids stuff like 美琳 to mean "beautiful jade" or 俊德 to mean "handsome virtue." also names are written [last] [first first]. atla kinda said "fuck it" and although characters have two-character first names, (idk about katara???) they don't... mean anything... like iroh's is 艾洛—艾 is more or less meaningless, and just a sound (ai) and 洛 is also more or less meaningless except for the sound (luo).

also not really a chinese language thing but... i keep seeing fics try to reference actual asian lit, and then just... failing... so uh, here's a crash course; traditional chinese poetry from the tang dynasty uses something called 五言绝句, aka there are four lines, and each line contains five characters (syllables). there are four big important novels, called 红楼梦 (kinda about forbidden romance),水浒传 (about a bunch of rebels sort of pursuing vigilante justice; each rebel has their own talent or skill), 三国演义 (...basically just a dramatic version of the warring states period?? lots of chinese idoms come from here, eg “说曹操他就到” which is basically "speak of the devil"),and 西游记(xuanzang the buddhist monk + his chaos gremlins (eg: monkey king) wreak havoc whilst xuanzang tries to find scriptures)。 another really famous romance is 梁山伯与祝英台, which is like forbidden love with a trans-ish twist. i'll make a post about these later, but please do your research, and don't just use characters from these in a shakespeare plot....

tl;dr

atla uses translation convention for speaking but not writing

atla script is basically traditional chinese, so no letters.

if we're assuming atla is in the 1850s, there are no punctuation or gendered third person pronouns. there are particles, which can kind of fill in gaps left by punctuation.

no one uses quills and everything is characters

learning to read/write takes up a substantial part of people's educations growing up, since its a pictorial language.

if you're gonna write about chinese classics, do it right.

#atla#avatar the last airbender#writing#chinese#chinese literature#crash coursing chinese lang???#mandarin#languages#gaang#zuko#katara#aang#toph#suki#sokka#asian languages#fanfic#writing advice#literacy#literature

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gwyndolin’s Names

[Obligatory disclaimer: I’m referring to Gwyndolin as ‘he’ throughout. I won’t judge you for doing as you prefer.]

Dark Sun Gwyndolin hides secrets, and even his name is no exception. Continuing the theme of Welsh names, he combines the elements “Gwyn” (fair or blessed) and “dolen” (ring, bow, hair, or brow). The interpretations “fair bow, blessed ring, white ring, who has white eyelashes'' are all applicable to Gwyndolin - evoked by the bow he wields in combat, the silver ring given to the Darkmoon Blades, and the pale brow and white hair of the Dark Sun.

The symbolism doesn't end there.

In Japanese, Gwyndolin’s title is 陰の太陽, “Sun in Shadow,'' an interesting phrase. On a surface level, “Dark Sun” nicely captures the imagery and inherent duality of the description, however, the English translation has lost a number of interesting details.

陰 does mean dark or shadowed, but it has multiple connotations.

Notably, 陰 “Shadow” is not the same as 闇, used throughout the game for the Dark. Likewise, 暗月 “Darkmoon” uses 暗 rather than 闇 to indicate darkness. Considering the precision with which Dark Souls uses language, I’m not going to suggest that Gwyndolin has anything to do with the true Dark.

陰 “Shadow” can also mean "behind the scenes" or "behind [someone's] back," which suits Gwyndolin’s role as the hidden enforcer. There is another commonly used kanji (影) that means 'shadow' and does not have those connotations, so I assume the choice is intentional.

The verb 陰げる, using the same root word, means ‘to become gloomy,' or 'to become hidden.' These meanings also apply well to Gwyndolin, hidden to disguise his “repulsive, frail” appearance.*

Expanding the search to words containing a given kanji is a reasonable way of learning about its historical use and connotations. By doing so, we find something interesting. 陰神 is an alternate writing of 女神 'goddess,' where 陰 is the Taoist principle better known by its Chinese name 'yin,' in contrast to the reading of 陽 as 'yang'.

Both are present in “Dark Sun” 陰の太陽. The phrase begins with ‘yin’ and ends with ‘yang!’ The Darkmoon deity metaphorically contains both the light and shadow, both the masculine and feminine, in tension.

To close the loop and provide another pointer to possible origins of the celestial themes of the gods, there are alternate kanji, specifically used for the Taoist principles. 陰 ‘yin’ can be written as 阴, and 陽 ‘yang’ can be written as 阳, respectively.

阴 'yin' is written with the radical 月’moon;’ 阳 'yang' is written with the radical 日 ‘sun.’ This in itself isn’t a strong statement; those kanji, after all, are not in use in Dark Souls, so far as I can tell.

It is interesting, in context of Gwyndolin’s “deep adoration of the sun,**” to note that the word used for Sun itself contains a reference to everything Gwyndolin is not permitted - masculinity, light, and a sense of order. Instead, he lives hidden, dressed and treated as a king’s daughter***, and punishes deviation from the divine order by means of the Blades. His name is emblematic of his personality and role, and in itself contains some of the contradictions that make Gwyndolin such a fascinating character.

-----

*Darkmoon Blade Covenant Ring description.

Gwyndolin, all too aware of his repulsive, frail appearance, created the illusion of a sister Gwynevere, who helps him guard over Anor Londo. An unmasking of these deities would be tantamount to blasphemy.

(I may not agree with this assessment of Gwyndolin’s appearance, but such is the way the story is told.)

**Crown of the Dark Sun description.

This crown of the gods demands faith immeasurable of its wearer, but it is imbued with Darkmoon power that enhances all magic. The image of the sun manifests Gwyndolin's deep adoration of the sun.

***Moonlight Robe description.

The power of the moon was strong in Gwyndolin, and thus he was raised as a daughter. His magic garb is silk-thin and hardly provides any physical defense.

#dark souls#dark souls meta#scholar of the dark#japanese language#fun with kanji#gwyndolin#dark sun gwyndolin

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kanji of the day: 嬉

嬉 - Glad, pleased, rejoice

Kun: うれ.しい、 たの.しむ

On: キ

(Pinyin: xī | xi1 )

Pictophonetic: 喜 represents the sound (pinyin xǐ | xi3), 女 (woman) represents the meaning

Can also be read as an ideograph, as 喜 means "to rejoice/take pleasure in".

Strokes: 15

Radical: 女 woman

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Originally posted on my cohost.

The End of IWAKAN Magazine

Have you ever discovered something so inspirational or fascinating only to find out that it's no longer around?

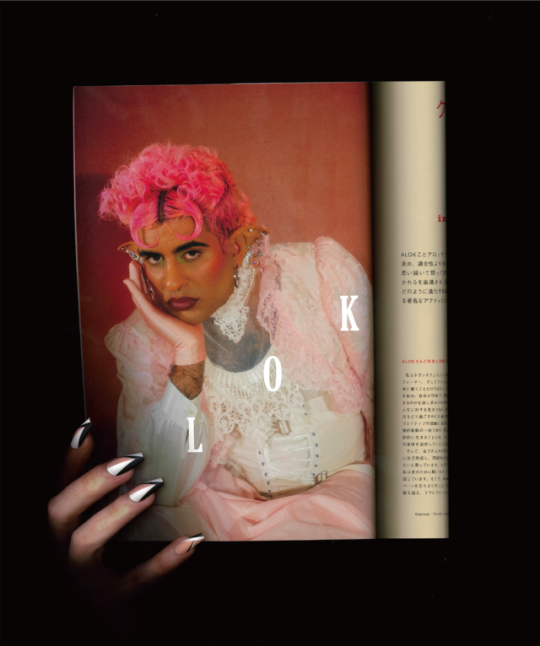

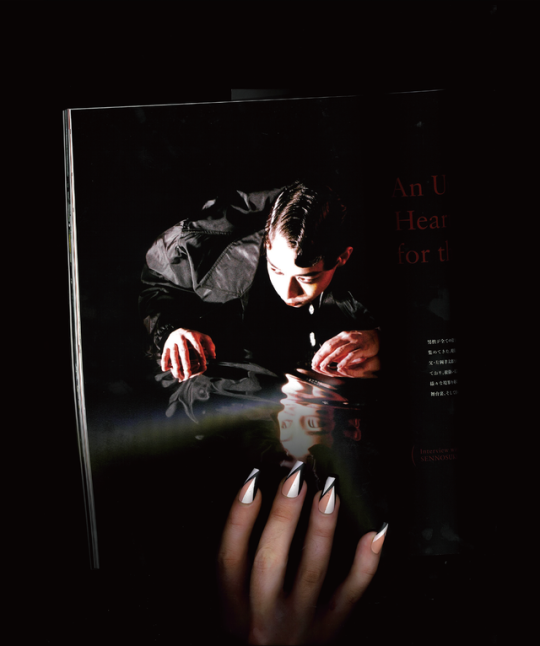

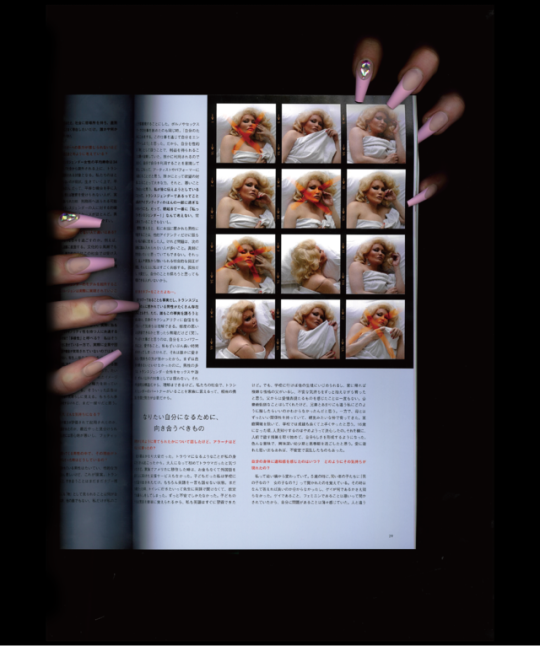

I heard about IWAKAN Magazine in November. Iwakan (違和感) is an uncomfortable feeling or sense of discomfort. The magazine's tagline is, 「IWAKANは、世の中の「当たり前」に「違和感」���問いかける雑誌です。」or "IWAKAN is a magazine that questions discomfort with what is "normal" in the world." It is part art magazine, part queer zine, part activist discourse, featuring interviews from a host of performers, drag queens, queer community activists, feminists from in and outside of Japan.

It started in October 2020, during the worst of the pandemic and published about an issue every six months including video interviews that are up on their Instagram. Looking at the contributors, there were many folks I know in the Japanese LGBTQIA+ community, many whom are personal friends, who were interviewed or made illustrations for the magazine.

There are interviews with Japanese trans men and nonbinary folks on how their relationship to masculinity has changed over time. With lesbian sex workers on how they approach love as entertainers. With kabuki performers about how they personally inhabit the masculine and feminine spheres as they switch roles. It's an incredible archive of personal stories from the Japanese community, and many are radical and awe-inspiring.

I have heard blanket statements about the LGBTQIA+ community in Japan—how it's behind the U.S. by twenty years or how the community is non-existent, and that it's hopeless. The government and laws in Japan are painfully slow to change. But it's personally frustrating for me because in the streets of Ni-chome I see people organizing, protesting, taking action and fighting. There is hope. And IWAKAN is a record of those conversations, especially during a time when people were sequestered in their homes.

On December 20th, 2023 IWAKAN posted a blank white square on their Instagram with the words, "The end - IWAKAN" and a brief message: "We know this is a sudden announcement, but IWAKAN will cease production as of the end of this year...thank you to everyone who supported us."

My heart fell into my stomach when I read that. Only a month after I discovered this publication and they were ceasing production. There will be no more IWAKAN this year, the year when Japanese government is hearing the lawsuit for same-sex marriage.

But those voices are still alive. And their website (for now) is still alive. So I wanted to share my discovery with you.

You can still buy IWAKAN...for now

Until the end of this month (January 31st, 2024) you can buy physical copies of IWAKAN magazine on their store. Volumes 01~05 are only in Japanese, and Volume 06 is in English and Japanese.

If you live in Japan, please consider buying a copy.

Official store is here.

I made an unofficial translated archive

At the end of the month when the store deactivates, I am worried that we will lose the summaries, table of contents, and photographs of the magazine as well as a critical piece of Japanese queer history.

The degradation of Site Formerly Known as Twitter and shifting TOS of social media has made me aware about how we preserve queer media, especially personal stories about sexuality and gender. Some of the images of the magazine would be flagged as "porn" by social media sites though in context they are about discussions of queer liberation in sexuality.

I decided to make a small archive of each of the IWAKAN issues with photos of them and English summaries, translated by me. I hope this can preserve a piece of history online for longer.

Volume 01 特集 女男 (Feminine/Masculine)

Volume 02 特集 愛情 (Love)

Volume 03 特集 政自 (Government/Individual)

Volume 04 特集 多様性?(Diversity?)

Volume 05 特集 (不)自然 ([Un]Natural)

Volume 06 特集 男性制 (Masculinity)

未来の男性へーIWAKAN書簡集 (Dear Future Men - Letters from IWAKAN)

Please be aware Japanese is not my mother tongue, so if I have made errors, please get in touch to let me know.

Please spread the word if you find this interesting and want to spread this gem of Japanese queer culture.

#iwakan#japanese#japanese culture#japan#queer community#queer#lgbtqia+#queer zines#patriarchy#queer activism#japanese queer culture#genderqueer#design#illustration#zines#trans community

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

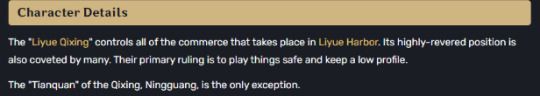

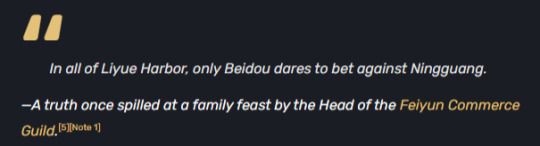

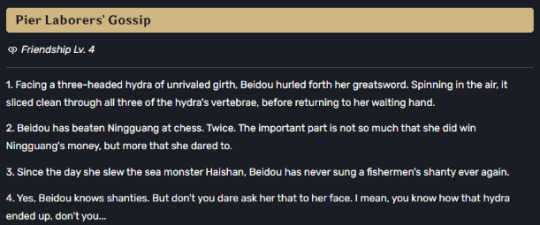

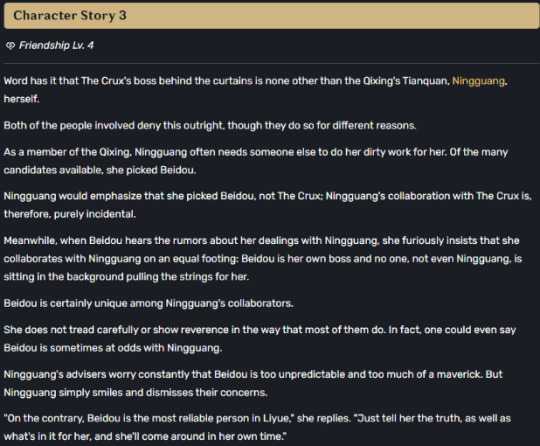

On beiguang, yin/yang symbolism and the blessed dragon/fenghuang pairing

The Beidou x Ningguang ship in Genshin is heavily inspired by two main symbols in Chinese culture: Yin and yang, and the dragon and fenghuang pairing. In this essay (literally) I will deep-dive into the nuances of these two symbols that make this ship so complex and enthralling to me at least?!

Yin/Yang

Let’s talk a bit about the concept of duality in Chinese cosmology. Yin and Yang are complementary forces that interact together to represent duality and balance in all aspects, i.e a shadow (Yin) cannot exist without light (Yang).

Yin and yang are always opposite and equal qualities. Whenever one quality reaches its peak, it will naturally begin the transformation into the opposite quality: for example, a flower that blooms in spring (fully Yang) will wither and die back in winter (fully Yin) in an endless cycle.

This can be applied to all cyclic events in life, for example the rise and fall of things: Yang being the rise and yin being the fall. Creation (Yang) and entropy (Yin) are also two sides of the same coin.

阴 Yin can be translated in several ways: the moon, concealed, overcast, hidden, shade. Generally, it represents the direction North.

The character 阴 can be broken down into two components:

The radical 阝, the graphical variant of 阜, meaning “mound, abundant, rich”,

and the character 月, meaning “moon”.

阳 Yang can be translated as, male, the sun, overt, belonging to this world, activity. Generally, it represents the direction South.

The character 阳 can also be broken down into two components:

The radical 阝, the graphical variant of 阜, meaning “mound, abundant, rich”,

and the character 日, meaning “sun”.

The terms “male” and “female” here don’t refer to gender specifically and are used very loosely – the Chinese believe in “feminine”/”negative” and “masculine”/”positive” energy as two halves of a whole, i.e. both must exist for balance to be. Neither can thrive without the other.

An interesting thing to note about Yin/Yang’s entomology is the way this phrase is written in Chinese. Chinese linguistics typically plac the “male”/”positive” energy first in the language, e.g. 男女, man-woman, and 天地, heaven and earth.

But in yinyang, 阴阳, the “female”/”negative” energy comes first. Scholars theorise that proto-Chinese society was perhaps matriarchal (Empress Dowager being more powerful than the Emperor), or that it was a way to challenge existing cultural preconceptions.

Dragon/Fenghuang

In Chinese mythology, the dragon and fenghuang are the two most powerful celestial symbols. The dragon represents "Yang" while the fenghuang represents "Yin”.

The Chinese dragon is traditionally drawn without wings. Oftentimes it may be depicted together with a flaming pearl under its chin or in its talons. The pearl is associated with spiritual energy, wisdom, prosperity, power, immortality, thunder (electro!), or the moon.

The fenghuang is sometimes referred to as the “Chinese phoenix”, but it has a completely different mythos to the Western legends of rebirth and fire.

The fenghuang is a peace-loving celestial being that is believed to only appear in places blessed with the utmost prosperity and happiness. It is said to live atop the Kunlun Mountains, the Chinese version of Mount Olympus.

Together, the dragon/fenghuang pairing is known as the celestial pairing. The fenghuang is a symbol of luck, prosperity, and success; the dragon is a symbol of status and power. The two are said to strengthen each other when paired. Their union is a symbol of matrimonial bliss and more importantly - balance.

Balance is a recurring theme in Beiguang, from Ningguang’s life and philosophy to Beidou’s (reluctant) admission that Ningguang balances her (more on that later when we deep dive into them individually).

It’s also worth noting that in some areas, the dragon/fenghuang symbol only appears to herald a new era - very much like what Liyue is going through now, heralding a new era of humans without an Archon’s guidance. And how fitting is it that the two most powerful women in Liyue now carry this symbol as they lead the nation into uncharted waters?

How Beiguang parallels Yin/Yang

The duality of Yin/Yang is visible in many aspects of life, from nature to society. One example is the sun moving across the sky. As the sun moves across the sky, things that are once illuminated (Yang) give way to shadow (Yin), revealing what was hidden, and hiding what was revealed.

Similarly, it represents the crux of Beidou and Ningguang’s relationship: infamously public yet ultimately secretive. The Captain and Tianquan talk about each other all the time, but what exactly is their deal? No one really knows.

Another example is their prized homes. The Jade Chamber is known to block out the moon over Liyue, yet is iconic in its skies – literally seen as the moon. It is passive in nature, still and motionless, and is also the epicentre of intelligence - aka covert activity. All these are symbols of Yin.

Now we don’t know exactly where True North is in Teyvat’s map, but Polaris, the North Star, has always been known as a fixed point in the sky, which is why sailors use it to navigate their way home.

Similarly, the Jade Chamber is this fixed point in the sky of Teyvat that could be used as a “North Star” to return to Liyue Harbour. North is, after all, the direction that Yin represents.

I digress a little here, but also consider that Beidou is the Chinese name of the Big Dipper, the very constellation used to point sailors towards Polaris. We know from Beidou’s namecard that she believes in looking to the skies when she wavers, and “the stars shall light the way”.

There’s a poetic beauty in the Jade Chamber being representative of Liyue’s Polaris, and Beidou finding her way back to her “North Star'' each time the Alcor sails for home.

Back on topic. In contrast, the Alcor on the other hand, is constantly moving and full of activity. It sails across the oceans; it is a symbol of power much like Beidou herself is (slayer of Haishan, Beidou tames the seas).

And just like the sun, the Alcor docks and leaves Liyue Harbour - a reflection of how only the sun travels across the sky, illuminating different sides of the moon that patiently waits for light to be cast upon its surface (again, something we’ll return to later).

Water itself can also be separated into Yin (still bodies, lakes) and Yang (moving water, river, ocean). The Jade Chamber is home to still bodies of water (Yin symbol) both inside and out; the Alcor’s very home is the ocean, a powerful Yang water symbol.

Ningguang and Yin/fenghuang symbolism

Alright, let’s deep-dive into Ningguang’s character first. Her strongest fenghuang link is seen mainly in her namecard, and it carries a lovely name:

凝光・凤仪 (Níngguāng - Fèngyí): the admiration/ceremony/rites of the fenghuang

The duality of the fenghuang

What’s interesting about the fenghuang is its duality: in ancient times, the fenghuang was a cohesive yin/yang symbol on its own. Over time when the dragon came into the picture, the fenghuang was altered. When paired with the dragon, it now symbolises Yin. But alone, it symbolises Yang instead.

And that’s why Ningguang’s storied history reflects elements of Yin/Yang balance. She rises (Yang) to power by herself; she retreats from the public eye, hiding (Yin) in the Jade Chamber, yet she is known to publicly flaunt (Yang) her position as a member of the Liyue Qixing.

The diverse nature of the fenghuang and its original symbolism as balance in and of itself contributes to Ningguang’s enigmatic nature, and why she has so many seemingly contradictory opinions - fame being usually associated with Yang, yet secrets being more of Yin.

When the dragon/Yang is not there, the fenghuang shines, becoming the “sun”/Yang - Ningguang is, after all, the de-facto leader of Liyue at this point. She has the awe and the attention of the masses, her chamber is unmissable, she is a ruthless business mogul yet adored by the children like an elder sister.

The parts of a fenghuang

It's also interesting to note that the fenghuang's body parts represent Ningguang's character well:

virtue (head),

duty (wings),

propriety (back),

credibility (abdomen),

and mercy (chest).

Beidou and Yang/dragon symbolism

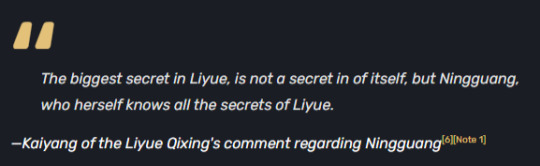

Perhaps the most obvious link between Beidou and the dragon is her Chinese title: 无冕的龙王 Wúmiǎn de Lóngwáng - “Uncrowned King of Dragons”.

She is specifically given the title “King”/王wáng instead of “Queen”/女王Nǚwáng - masculine energy being a strong Yang quality.

A symbol of Yang quality

Unlike the fenghuang, the Chinese dragon has always been a representation of Yang, which is why Beidou’s character very clearly represents the quintessence of Yang: well-liked, respected, reputed, masculine (in her feats - slaying Haishan, leading a pirate fleet, taming the seas), always on the move, never on land for long.

Traditionally, the dragon has always symbolised power and confidence. The Chinese dragon is the ruler of water and weather, especially moving bodies of water such as the sea, which might suggest why Beidou is able to navigate the sea so very well, to the point that her crew “believe her capable of taming the storms and billows on the sea.”

She also “understands” the sea almost intimately, as seen in her CN voiceline “About us: an eye for people”:

“I’m good at reading people. When you’ve seen the wide ocean, the little splashes (changes) on people’s faces are just too easy to understand. Haha, so, I noticed you from the start.”

Beidou refers to the “changes on people’s faces” as “小水花/splashes (of water)”, implying that once you learn to read the sea (often known as a cruel mistress), people become easy to read in comparison. And to read the sea, you observe. You study every wave, every detail, so you can understand her subtleties.

Despite being a pirate, Beidou’s dragon-symbolic traits show up in her honourable personality, her ability to command the loyalty of her crew, and her commitment to helping the less fortunate.

The dragon's history

Initially, the dragon was benevolent, wise and just, but the introduction of Buddhism added malevolent influence to the dragons. Water can raise and water can destroy. So dragons became able to destroy through floods, tsunamis and storms.

Similarly, that could also be why Beidou, although symbolising the dragon, was also named to be a cursed child – perhaps a tribute to the dragon’s newfound duality.

Yin/Yang Symbolism in relation to Beiguang

Okay, we’ve got that all down, so now we can study Beiguang in the context of Yin/Yang and dragon/fenghuang symbolisms. Remember the bit earlier about how the sun is the only celestial body to travel across the sky in astrologers’ eyes, illuminating different sides of the moon?

Present-day Ningguang resides in Liyue Harbour and (as far as we know) rarely leaves the nation. Beidou comes and goes as the sun rises and falls, and it is with her return that we have been seeing different facets of Ningguang come alive under the light of the sun (Yang).

Ningguang has a voiceline in particular titled “About Us: Observing”. There is one key difference in the CN version of this voiceline, which I’ll translate:

“You’ve followed me for so long, (I’m sure) you’ve learned how to observe. Then, try to observe me, until you become my trusted confidant.”

She asks Traveler to observe her. But what can you observe in the obscured until it is illuminated? Who illuminates her beyond the Tianquan that the masses know?

Most of the key Liyue events in 2021 featuring Ningguang, Archon Quest aside, have also featured Beidou in some capacity. And we learn the most about Ningguang from and through Beidou, like how Yang casts light on and reveals what was previously hidden (Yin).

Romantic gestures aside, their business relationship is also reflective of the dragon/fenghuang motif. Now the dragon symbolises the Chinese Emperor, known as a descendent of the celestial dragons, and the fenghuang symbolises the Empress. To be more specific, the fenghuang represents "power sent from the heavens'' to the Empress.

This brings me back to the way Yinyang is written: female first.

Traditionally although the empress dowager (Yin, fenghuang) supposedly holds more power than the Emperor (Yang, dragon), she works from the shadows, often more covertly. For all intents and purposes, the emperor has the final say. Similarly, Ningguang uses Beidou to do her dirty work.

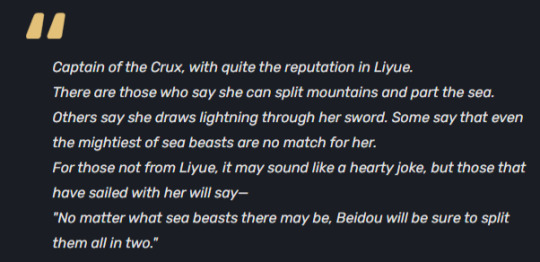

Yin/Yang - two halves of a whole

Beiguang is essentially a perfectly balanced couple, and the game alludes to this in various ways. One is this interaction between Paimon and Beidou during Moonchase, after Ningguang and Beidou have their little squabble in front of the giant rock and all their friends:

The idiom she uses for "evenly-matched" (势均力敌) is usually used in context of a game/polls/tournament/etc. If you break down the etymology, it literally means "power/influence are equal (in a situation), (so our) strengths match".

Reminder that yin and yang are not just equals - they are also opposite qualities. Life and death, light and darkness, rise and fall. This is why Beidou and Ningguang “profess antipathy to each other’s way of life”, and yet they are united for Liyue’s greater good. They are the direct opposites of each other (law vs crime, elegance vs boorish, luxurious vs simple, light vs dark), but they are also equals.

And Ningguang values this very much -

“Of the many candidates available, she picked Beidou.”

She values time as her greatest resource, making businessmen bid for her time - but Beidou is given the permission to “come up any time” for a game of chess.

All that said, their yin/yang dynamic is not new in Chinese romance stories. Off the top of my head, the titular characters of C-drama Who Rules The World essentially share the same Yin/Yang dynamic as Beiguang does. It’s a lovely trope that adds great complexity to character dynamics.

I do love how hyv has interwoven the dragon/fenghuang symbolisms deep into their lives however, such that Ningguang and Beidou both live and breathe the cultural symbols that they are inspired by, rather than letting it simply be a romantic trope.

Beiguang nation, this be my first gift to you. Hope it’s been a fun read! Next up: GINKGOS.

Beiguang masterlist

#beiguang#genshin impact#genshin lore#genshin analysis#yinyang#dragon and phoenix#chinese culture#beidou x ningguang#beidou#ningguang#ship dynamics#otp dynamics#my otp forever#umm im tryna figure out how to format stuff here#sorry if things look messy or low quality#beiguang dynamics

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

Common radicals

After seeing this post by @don-dake (which was very helpful for me to learn the different forms radicals can take), I decided to write one myself about the following radicals (部首, bùshǒu):

(The ones in the picture are traditional characters, but I use simplified characters in this post.)

哲理类 (zhélǐlèi) - philosophical category

日 (rì) - day, sun

月 (yuè) - moon

金 (jīn) - gold

木 (mù) - wood

水 (shuǐ) - water

火 (huǒ) - fire

土 (tǔ) - earth

笔画类 (bǐhuàlèi) - stroke category

竹 (zhú) - bamboo

戈 (gē) - halberd

十 (shí) - ten

大 (dà) - big

中 (zhōng) - middle

一 (yī) - one

弓 (gōng) - bow

人体类 (réntǐlèi) - human body category

人 (rén) - person

心 (xīn) - heart

手 (shǒu) - hand

口 (kǒu) - mouth

字形类 (zìxínglèi) - typographic category

尸 (shī) - corpse

廿 (niàn) - twenty

山 (shān) - mountain

女 (nǚ) - woman

田 (tián) - field

卜 (bo) - to predict

难子 (nánzi) - difficult words

难 (nán) - disaster

[I haven't been able to find some of the characters (neither in their traditional or simplified forms) in this category, and I'm not sure whether the ones I've found are the right ones, so if anybody could enlighten me, I would be very grateful 🥺]

齐 (qí) - identical

龟 (guī) - turtle, tortoise

臼 (jiù) - mortar

渊 (yuān) - abism

?

?

?

昍 (xuān) - brilliant

?

身 (shē) - body

?

?

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

日本電子歌謡局

TECHNOLOGY J-POP STATION

YMO、P-MODEL、ヒカシュー、プラスティックス、昭和のアイドル・テクノ歌謡から

平成の電気グルーヴ、スーパーカー、サカナクション、Perfumeまで

日本産・ピコピコ・エレクトロ度高めのテクノポップのパーティーです。

そして4/21にデビュー40周年を迎えるTM NETWORKのトリビュートタイムもあります!

Welcome to the FANKS!!

youtube

2024/4/20(土)

20:00-25:00

チャージ無料/1ドリンクオーダー

at Music Bar "JUKE JOINT"

福岡県福岡市中央区舞鶴1丁目9-23

DJ / kunny YAS 超わかな kkna IWAO Kawaknown

VJ / Tagami

-----Mix CD Track List-----

日本電子歌謡局 TECHNOLOGY J-POP STATION

DJ Mixed by Kawaknown

[Track 1]

真鍋ちえみ / 不思議・少女

TM NETWORK / Rainbow Rainbow

RADICAL TV / X.Y.Z

Logic System / Merry Chistmas Mr. Lawrence

YELLOW MAGIC ORCHESTRA / Cue

METAFIVE / 環境と心理

DATE OF BIRTH / Remember Eyes

坂本龍一 / Ballet Mecanique

YELLOW MAGIC ORCHESTRA / Behind The Mask

PLASTICS / Delicious

風見慎吾 / 涙のtake a chance

細野晴臣 / コズミック・サーフィン

電気グルーヴ / Shangri-La

坂本龍一 / SELF PORTRAIT

安田成美 / 銀色のハーモニカ

[Track 2]

戸川純 / 好き好き大好き

ヒカシュー / モデル

YELLOW MAGIC ORCHESTRA / 君に、胸キュン。

越美晴 / 走れウサギ

大和田りつこ / 宇宙人のテレパシー

PIC / ROLLING AGE

P-MODEL / Speed Tube

Perfume vs. 電気グルーヴ / Laser Beam Popcorn

TM NETWORK / Children of the New Century (FINAL MISSION)

サカナクション / アルクアラウンド (Metalmaster Remix)

岡村靖幸 / ぶーしゃかLOOP

電気グルーヴ / Flashback Disco

近田春夫 / エレクトリック・ラブ・ストーリー

藤村美樹 / 夢・恋・人

藤井隆 / わたしの青い空

SOFT BALLET / BODY TO BODY

Perfume / チョコレイト・ディスコ

Perfume / ポリリズム

TM NETWORK / Get Wild

#undercurrent_bootleg#ymo#yellow magic orchestra#細野晴臣#坂本龍一#高橋幸宏#metafive#戸川純#TM Network#テクノポップ#テクノ歌謡#DJ#80年代#Youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

I feel you so much on the "native Chinese speaker accidentally mis-gendering people in English" thing so much. People (native English speakers) get so mad and they never believed me when I tried to explain that pronouns just aren't part of the sentence construction process when I speak, especially when I already have so many other things to consider and translate on the fly.

yes! neat to hear that it's not just me and my older family members with this problem lol. if it's your first language and that was never... part of the cognition required to communicate while speaking it can be a tough thing to learn, and justifiably frustrating. while i'm first-gen, i learned english quite early and adapted over time, a lot of people who learn english coming from a more gender-neutral language never quite slough it off, and i suppose have to brace themselves for the imminent social faux-pas that it tends to be.

(some context for english speakers, there's usually what we consider two third-person pronouns in written chinese: 他 ["he"] and 她 ["she"]. note that they differ on the radical on the left side.

他/她 sound identical, and there's a historical reason for this: there used to only be one third-person pronoun, and was therefore by default the english equivalent of "they," which was 他. the radical on the left can be written alone as 人, which simply translates to "person."

its widespread shift to a masculine pronoun and the introduction of 她 [the radical on the left, 女, tends to translate to "woman" or "daughter"] is only about a hundred years old. why fix what's not broken? the most common reason cited is increased western contact and their complaint that the ambiguity of a single gender-neutral pronoun made translating chinese confusing. it is, quite literally, a cultural accomodation [and more explicitly a colonial one, if you want my opinion on it. lol])

#oh look i overexplained again#thanks for weighing in!! and hugs. adapting to a new language can be hard#ask

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

An adorable and unusual nameplate, and a pretty name! The surname 栗津 can be read Kuritsu or Awazu.

栗, which is made up of 木 tree and 西 west, means chestnut. It can be read くり (the word for chestnut) or おののく, リツ, or リ.

It's easy to mistake for 粟 millet (which has 米 rice on the bottom) or 要 need (which has 女 woman on the bottom (about which I will refrain from comment at this time)).

津, as you might remember, means haven, port, harbor, or ferry. It's read つ or シン. It's made up of 氵 the water radical and 聿 the brush radical (yes, the top part of 書, meaning to write).

32 notes

·

View notes