#moderngreek

Text

Greek chic

Opa. Get ready to bring some Greek chic vibes into your life with these playful and stylish Pins.

0 notes

Text

Erasmian vs. Modern Pronunciation: Philological & Linguistic Considerations

Researched by Eli Kittim

I’m not a linguist and I will not illustrate phonetic diagrams in philological nomenclature (e.g. IPA, etc.) lest I lose the audience's attention with such complicated jargon. I’m simply trying to understand the literature and summarize it in the best possible way. Since there’s not much interest in Ancient Greek pronunciation on the web, I compiled some material from a handful of links that might be of interest. Most of the paper is actually excerpted from various articles that are mentioned at the end of the paper.

——-

The History of the Reconstructed Pronunciation of Greek

“The study of Greek in the West expanded considerably during the Renaissance, in particular after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, when many Byzantine Greek scholars came to Western Europe. Greek texts were then universally pronounced with the medieval pronunciation that still survives intact.

From about 1486, various scholars (notably Antonio of Lebrixa, Girolamo Aleandro, and Aldus Manutius) judged that the pronunciation was inconsistent with the descriptions that were handed down by ancient grammarians, and they suggested alternative pronunciations. This work culminated in Erasmus's dialogue De recta Latini Graecique sermonis pronuntiatione (1528). The system that he proposed is called the Erasmian pronunciation. The pronunciation described by Erasmus is very similar to that currently regarded by most authorities as the authentic pronunciation of Classical Greek (notably the Attic dialect of the 5th century BC).” [1]

——-

The Reuchlinian Model

“Johann Reuchlin (1455 – 1522) was a German Catholic humanist and a scholar of Greek and Hebrew.” [2]

“Reuchlin, it may be noted, pronounced Greek as his native teachers had taught him to do, i.e., in the modern Greek fashion. This pronunciation, which he defends in De recta Latini Graecique sermonis pronuntiatione (1528), came to be known, in contrast to that used by Desiderius Erasmus, as the Reuchlinian.” [3]

“Among speakers of Modern Greek, from the Byzantine Empire to modern Greece, Cyprus, and the Greek diaspora, Greek texts from every period have always been pronounced by using the contemporaneous local Greek pronunciation. That makes it easy to recognize the many words that have remained the same or similar in written form from one period to another. Among Classical scholars, it is often called the Reuchlinian pronunciation, after the Renaissance scholar Johann Reuchlin, who defended its use in the West in the 16th century.” [4]

“The theology faculties and schools related to or belonging to the Eastern Orthodox Church use the Modern Greek pronunciation to follow the tradition of the Byzantine Empire.” [5]

“The two models of pronunciation became soon known, after their principal proponents, as the ‘Reuchlinian’ and the ‘Erasmian’ system, or, after the characteristic vowel pronunciations, as the ‘iotacist’ (or ‘itacist’) and the ‘etacist’ system, respectively.” [6]

“The resulting debate, as it was conducted during the 19th century, finds its expression in, for instance, the works of Jannaris (1897) and Papadimitrakopoulos (1889) on the anti-Erasmian side, and of Friedrich Blass (1870) on the pro-Erasmian side.” [7]

“The resulting majority view today is that a phonological system roughly along Erasmian lines can still be assumed to have been valid for the period of classical Attic literature, but biblical and other post-classical Koine Greek is likely to have been spoken with a pronunciation that already approached that of Modern Greek in many crucial respects.” [8]

——-

Controversies about Reconstructions

“The Greek language underwent pronunciation changes during the Koine Greek period, from about 300 BC to 300 AD. At the beginning of the period, the pronunciation was almost identical to Classical Greek, while at the end it was closer to Modern Greek.” [9]

“The primary point of contention comes from the diversity of the Greek-speaking world: evidence suggests that phonological changes occurred at different times according to location and/or speaker background. It appears that many phonetic changes associated with the Koine period had already occurred in some varieties of Greek during the Classical period.” [10]

“An opposition between learned language and vulgar language has been claimed for the corpus of Attic inscriptions. Some phonetic changes are attested in vulgar inscriptions since the end of the Classical period; still they are not generalized until the start of the 2nd century AD in learned inscriptions. While orthographic conservatism in learned inscriptions may account for this, contemporary transcriptions from Greek into Latin might support the idea that this is not just orthographic conservatism, but that learned speakers of Greek retained a conservative phonological system into the Roman period. On the other hand, Latin transcriptions, too, may be exhibiting orthographic conservatism.” [11]

“Interpretation is more complex when different dating is found for similar phonetic changes in Egyptian papyri and learned Attic inscriptions. A first explanation would be dialectal differences (influence of foreign phonological systems through non-native speakers); changes would then have happened in Egyptian Greek before they were generalized in Attic. A second explanation would be that learned Attic inscriptions reflect a more learned variety of Greek than Egyptian papyri; learned speech would then have resisted changes that had been generalized in vulgar speech.” [12]

By the 4th century, “The pronunciation suggested here, though far from being universal, is essentially that of Modern Greek except for the continued roundedness of /y/.” [13]

Single Vowel Quality

“Apart from η, simple vowels have better preserved their ancient pronunciation than diphthongs. As noted above, at the start of the Koine Greek period, pseudo-diphthong ει before consonant had a value of /iː/, whereas pseudo-diphthong ου had a value of [uː]; these vowel qualities have remained unchanged through Modern Greek. Diphthong ει before vowel had been generally monophthongized to a value of /i(ː)/ and confused with η, thus sharing later developments of η. The quality of vowels α, ε̆, ι and ο have remained unchanged through Modern Greek, as /a/, /e/, /i/ and /o/. The quality distinction between η and ε may have been lost in Attic in the late 4th century BCE, when pre-consonantic pseudo-diphthong ει started to be confused with ι and pre-vocalic diphthong ει with η. C. 150 AD, Attic inscriptions started confusing η and ι, indicating the appearance of a /iː/ or /i/ (depending on when the loss of vowel length distinction took place) pronunciation that is still in usage in standard Modern Greek.” [14]

Consonants

“The consonant ζ, which had probably a value of /zd/ in Classical Attic (though some scholars have argued in favor of a value of /dz/, and the value probably varied according to dialects – see Zeta (letter) for further discussion), acquired the sound /z/ that it still has in Modern Greek, seemingly with a geminate pronunciation /zz/ at least between vowels. Attic inscriptions suggest that this pronunciation was already common by the end of the 4th century BC.” [15]

——-

A Critique of Erasmus’ Knowledge & Methadology

Erasmus “succeeded in learning Greek by an intensive, day-and-night study of three years.” [16] That’s hardly the time needed to become competent in Greek. What is more, he sometimes confused the Greek with the Latin:

“In a way it is legitimate to say that Erasmus ‘synchronized’ or ‘unified’ the Greek and the Latin traditions of the New Testament by producing an updated translation of both simultaneously. Both being part of canonical tradition, he clearly found it necessary to ensure that both were actually present in the same content. In modern terminology, he made the two traditions ‘compatible.’ This is clearly evidenced by the fact that his Greek text is not just the basis for his Latin translation, but also the other way round: there are numerous instances where he edits the Greek text to reflect his Latin version. For instance, since the last six verses of Revelation were missing from his Greek manuscript, Erasmus translated the Vulgate's text back into Greek. Erasmus also translated the Latin text into Greek wherever he found that the Greek text and the accompanying commentaries were mixed up, or where he simply preferred the Vulgate's reading to the Greek text.” [17]

His 1516 publication became the first published New Testament in Greek:

“Erasmus used several Greek manuscript sources because he did not have access to a single complete manuscript. Most of the manuscripts were, however, late Greek manuscripts of the Byzantine textual family and Erasmus used the oldest manuscript the least because ‘he was afraid of its supposedly erratic text.’ He also ignored much older and better manuscripts that were at his disposal.” [18]

So although the modern critical edition of the New Testament rejected Erasmus’ versions, those same scholars that sat on these editorial committees nevertheless adopted his pronunciation (odd)❗️

On the other end of the spectrum, Johann Reuchlin was a German Catholic who had no axe to grind. He neither defended the Eastern Orthodox Church nor the Greek heritage per se. So he had no conflict of interests. He didn’t have a dog in this fight, so to speak. His interest was purely intellectual and academic.

——-

German Reconstructions

“The situation in German education may be representative of that in many other European countries. The teaching of Greek is based on a roughly Erasmian model, but in practice, it is heavily skewed towards the phonological system of German or the other host language.

Thus, German-speakers do not use a fricative [θ] for θ but give it the same pronunciation as τ, [t], but φ and χ are realised as the fricatives [f] and [x] ~ [ç]. ζ is usually pronounced as an affricate, but a voiceless one, like German z [ts]. However, σ is often voiced, according like s in German before a vowel, [z]. ευ and ηυ are not distinguished from οι but are both pronounced [ɔʏ], following the German eu, äu. Similarly, ει and αι are often not distinguished, both pronounced [aɪ], like the similar German ei, ai, and ει is sometimes pronounced [ɛɪ].” [19]

“While the deviations are often acknowledged as compromises in teaching, awareness of other German-based idiosyncrasies is less widespread. German-speakers typically try to reproduce vowel-length distinctions in stressed syllables, but they often fail to do so in non-stressed syllables, and they are also prone to use a reduction of e-sounds to [ə].” [20]

French Reconstructions

“Pronunciation of Ancient Greek in French secondary schools is based on Erasmian pronunciation, but it is modified to match the phonetics and even, in the case of αυ and ευ, the orthography of French.” [21]

“Vowel length distinction, geminate consonants and pitch accent are discarded completely, which matches the current phonology of Standard French. The reference Greek-French dictionary, Dictionnaire Grec-Français by A. Bailly et al., does not even bother to indicate vowel length in long syllables.” [22]

“The pseudo-diphthong ει is erroneously pronounced [ɛj] or [ej], regardless of whether the ει derives from a genuine diphthong or a ε̄. The pseudo-diphthong ου has a value of [u], which is historically attested in Ancient Greek.” [23]

“Short-element ι diphthongs αι, οι and υι are pronounced … as [aj], [ɔj], [yj], [and] … some websites recommend the less accurate pronunciation [ɥi] for υι. Short-element υ diphthongs αυ and ευ are pronounced like similar-looking French pseudo-diphthongs au and eu: [o]~[ɔ] and [ø]~[œ], respectively.” [24]

“Also, θ and χ are pronounced [t] and [k]. … Also, γ, before a velar consonant, is generally pronounced [n]. The digraph γμ is pronounced [ɡm], and ζ is pronounced [dz], but both pronunciations are questionable in the light of modern scholarly research.” [25]

Italian Reconstructions

“Italian speakers find it hard to reproduce the pitch-based Ancient Greek accent accurately so the circumflex and acute accents are not distinguished. … β is a voiced bilabial plosive [b], as in Italian bambino or English baby; γ is a voiced velar plosive [ɡ], as in Italian gatto or English got. When γ is before κ γ χ ξ, it is nasalized as [ŋ] … ζ is a voiced alveolar affricate [dz], as in Italian zolla … θ is taught as a voiceless dental fricative, as in English thing [θ], but since Italian does not have that sound, it is often pronounced as a voiceless alveolar affricate [ts], as in Italian zio, or even as τ, a voiceless dental plosive [t]) … χ is taught as a voiceless velar fricative [x], as in German ach, but since Italian does not have that sound, it is often pronounced as κ (voiceless velar plosive [k]).” [26]

Spanish Reconstructions

Due to Castilian Spanish, “phonological features of the language sneak in the Erasmian pronunciation. The following are the most distinctive (and frequent) features of Spanish pronunciation of Ancient Greek: following Spanish phonotactics, the double consonants ζ, ξ, ψ are difficult to differentiate in pronunciation by many students of Ancient Greek, although ξ is usually effectively rendered as [ks]; … both vocalic quantity and vowel openness are ignored altogether: thus, no effort is made to distinguish vocalic pairs such as ε : η and ο : ω; the vowel υ, although taught as [y] (absent in the Spanish phonological system), is mostly pronounced as [i].” [27]

——-

What Do the Experts Say?

Nick Nicolas, PhD in Modern Greek dialectology & linguist at Thesaurus Linguae Graecae, outlines the 3 current pronunciation models of Ancient Greek:

1. Erasmus' reconstruction of Ancient Greek phonology, as modified in practice for teaching Greek in Western schools.

2. The scholarly reconstruction of Ancient Greek phonology.

3. Modern Greek pronunciation applied to Ancient Greek (“Reuchlinian" pronunciation). [28]

Nicolas’ Critique of Erasmian:

It's not quite fully there with the scholarly

reconstruction of Greek; so some of the

phonology and morphology of Ancient

Greek still doesn't make sense.

Particularly with diphthongs, and

aspiration, if your local Erasmian doesn't

do them accurately. [29]

“Extreme variability from country to country, because of the concessions each country's teaching system makes to the local language.

Speak in Erasmian to a Greek, and they'll look at you like a space alien. … But they will genuinely have no idea what you are saying, or what language you are saying it in. … It's quite far from Koine. Koine was still in flux, and some critical changes were underway when the bit of Koine most people care about (New Testament) was spoken. But overall, Koine was much closer to Modern Greek than Homeric.” [30]

——-

Here’s what Daniel Streett, Ph.D & Associate Professor of Biblical Studies at Houston Baptist University, says about the pronunciations debate that occurred approximately 10 years ago at the annual Society of Biblical Literature meeting in San Francisco. It was sponsored by the Biblical Greek Language and Linguistics Section & the Applied Linguistics for Biblical Languages Group, which addressed the topic of Greek phonology and pronunciation.

Dr. Daniel Streett says:

“There is a widespread consensus among historical linguists as to how Greek was pronounced at its various stages. If you want a good summary of the consensus, check out A.-F. Christidis’ History of Ancient Greek, which has several articles on the various phonological shifts. Especially relevant is E.B. Petrounias’ contribution on ‘Development in Pronunciation During the Hellenistic Period’ (pp. 599-609).” [31]

Then he critiques the Erasmian Pronunciation that was presented by Daniel Wallace of Dallas Seminary. Dr. Streett writes:

“He was asked to argue for the Erasmian pronunciation, although, as he explained at the outset, he has no firm conviction that Erasmian pronunciation best reflects the way Greek was pronounced in the Hellenistic world.

I found Wallace’s presentation very easy to follow and enjoyable to listen to, but frustrating at the same time. I think he seriously misrepresented the state of our knowledge on Greek phonology in the Hellenistic and Roman imperial eras. He did not deal with any hard evidence from manuscripts or inscriptions (as subsequent presenters Buth and Theophilos did). He merely pointed out a few of the difficulties with assessing such evidence and then (IMO) cavalierly dismissed them.” [32]

Dr. Streett Comments on the Reconstructed Koine:

“Randall Buth of the Biblical Language Center presented third and advocated his reconstruction of 1st century Koine Greek. If you want a summary of his system, take a look at his page on it here: https://www.biblicallanguagecenter.com/koine-greek-pronunciation/

Buth’s presentation contained what Wallace’s lacked: a lot of evidence which demonstrated that however they were pronouncing Greek in the first century, it sure wasn’t Erasmian! Furthermore, he showed that the regional differences objection did not really hold, as the same sounds were ‘confused’ in texts from across the ancient world. So, while the pronunciation might have differed slightly from region to region, the phonemic structure remained stable.

Neo-hellenic or Modern Pronunciation

Michael Theophilos, who teaches at Australian Catholic University, presented last and advocated the modern pronunciation. Theophilos speaks modern Greek but also believes that most (or all?) of the modern phonology was in place by the first century. He made some very helpful methodological points. For example, he argues that we should be looking for phonological clues mainly in the non-literary papyri, which are more likely to contain phonetic spellings. He also offered several examples of iotacism in early papyri to show that there is at least some evidence that οι, η, and υ had iotacized by the 2nd century CE.

By the time you heard Simkin, Buth, and Theophilos, Wallace’s agnosticism seemed thorougly untenable. Theophilos didn’t have a whole lot to say about the practical reasons for using the modern pronunciation. I wish he would have, since it’s helpful for Erasmians to realize there’s an entire country of people who speak Greek and can’t bear to listen to the awful linguistic barbarity known as Erasmian. When Wallace was making the argument that Erasmians are by far in the pedagogical majority, he conveniently left out the millions of Greek students on this little peninsula in the Aegean.” [33]

——-

Conclusion

In the words of Daniel B. Wallace:

“Erasmian pronunciation is often considered cumbersome, unnatural, stilted, and ugly. The implication sometimes is that it must not have been the way Greek ever sounded; it is too harsh on the ears for that.” Not to mention fake and fabricated!

As regards Koine Greek, no one from our generation was there to hear the words being spoken. So no one really knows exactly how it sounded. But just as the closest pronunciation to Middle English is Modern English, so the rightful heir and descendant of Koine Greek pronunciation is obviously Modern Greek. It should be closer to the Koine Greek pronunciation than an invented phonetic system from the Renaissance. Just as Albert Schweitzer realized that most authors had interpreted Jesus in their own image, so Erasmians have interpreted Greek pronunciation in their own image as well. That’s why the Erasmian speakers don’t sound Greek but have the accents of their native countries.

What is more, many of their theories are erroneously based on Egyptian Greek papyri. Suppose that 2,000 years from now linguists try to reconstruct American pronunciation via English literature that was found in Australia. The pronunciations are vastly different. By comparison, what was spoken in Egypt or Palestine was certainly not spoken in Athens.

Besides, there’s much more literature on Erasmian pronunciation and a relative neglect or disinterest to write anything about the Reuchlinian or Modern Greek pronunciation. That’s a western bias that has been in place for centuries.

Let’s not forget that we learned so much about Koine Greek from the discoveries of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, such as the Oxyrhynchus Papyri, the Dead Sea Scrolls, and the like. The addition of approximately 5,800 New Testament mss. that we currently have just in Greek, compared to a handful that Erasmus had at his disposal, shows how much more equipped we are in understanding the intricacies and complexities of Koine Greek than he was in the early 1500s.

Philemon Zachariou——Ph.D Bible scholar, linguist, & native Greek speaker——uses various lines of evidence, including Plato’s writings, to show that ι = ει = η = [i] (kratylos 418c) is similar to Neohellenic Greek. He summarizes the evidence as follows:

“iotacism is not a ‘modern’ development but is traceable all the way to Plato’s day.” He further claims that “the phonemic sounds of mainstream Modern Greek are not ‘modern’ or new but historical; and the Modern Greek way of reading and pronouncing consonants, vowels, and vowel digraphs was established by, or initiated within, the Classical Greek period (500-300 BC).” [34]

He concludes that no pronunciation comes closer to Koine than Modern Greek.

Similarly, David S. Hasselbrook, who studies New Testament Lexicography, says that a number of new words that occur in the New Testament continue to have the same meanings in modern Greek. These words are closer to modern Greek than Classical Greek. Constantine R. Campbell, Associate Professor of New Testament at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, also says that Modern Greek helps to resolve text-critical issues related to pronunciation, whereas the Erasmian may lead down the wrong path! [35]

——-

Notes

1 Pronunciation of Ancient Greek in teaching (Wiki).

2 Johann Reuchlin (Wikipedia).

3 Ibid.

4 Pronunciation of Ancient Greek in teaching.

5 Ibid.

6 Ancient Greek phonology (Wikipedia).

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Koine Greek phonology (Wikipedia).

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Erasmus (Wikipedia).

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 Pronunciation of Ancient Greek in teaching.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid.

28 What are the pros and cons of the Erasmian

pronunciation? (Quora).

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid.

31 The Great Greek Pronunciation Debate (SBL)

32 Ibid.

33 Ibid.

34 Philemon Zachariou, PhD - YouTube Video

35 Ibid.

A Comparison Between Erasmian & Modern Pronunciation

Matthew 7 - Erasmian Pronunciation -https://youtu.be/vKrqwhBwur8

youtube

Matthew 7 - Modern Greek Pronunciation -https://youtu.be/ktmnpVzxPw4

youtube

——-

Selected Bibliography

Allen, William Sidney (1987). Vox Graeca. A Guide to the Pronunciation of Classical Greek (3rd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. ix–x. ISBN 978-0-521-33555-3. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

Jannaris, A. (1897). An Historical Greek Grammar Chiefly of the Attic Dialect As Written and Spoken From Classical Antiquity Down to the Present Time. London: MacMillan.

Papadimitrakopoulos, Th. (1889). Βάσανος τῶν περὶ τῆς ἑλληνικῆς προφορᾶς Ἐρασμικῶν ἀποδείξεων [Critique of the Erasmian evidence regarding Greek pronunciation]. Athens.

https://en-academic.com/dic.nsf/enwiki/1466927

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Koine_Greek_phonology

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pronunciation_of_Ancient_Greek_in_teaching

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iotacism

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erasmus

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Reuchlin

https://quora.opoudjis.net/2016/01/24/2016-01-24-what-are-the-pros-and-cons-of-the-erasmian-pronunciation/

https://danielstreett.com/2011/12/01/the-great-greek-pronunciation-debate-sbl-2011-report-pt-3/amp/

https://youtu.be/wYtrVlpnpg4

youtube

#erasmus#classical greek#philology#linguistics#restoredpronunciation#reconstructedpronunciation#Elikittim#thelittlebookofrevelation#το_μικρό_βιβλίο_της_αποκάλυψης#ek#ελικιτίμ#εκ#ancient greek#KoineGreek#modernGreek#modernpronunciation#Reuchlin#Iotacism#acoustic#Erasmian#attic greek#phonological#phonetics#AntoniusNJannaris#EasternOrthodoxChurch#GeorgiosNicolaouHatzidakis#TheodorosPapadimitrakopoulos#ChrysCCaragounis#AlexandrosRhizosRhankabes#EdmundMartinGeldart

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Πιάσε (Pía-za), 2018-2019, plaster, chains, glitter foam paper, spray paint, glitter, stuffed sculpture with handmade rope, draped satin, and various fabrics, and printed images of ancient columns in various colors, 10 ft x 10 ft x 10 ft.

Πιάσε (Pía-za) re-imagines ancient Greek culture from my perspective as a contemporary, queer Greek-American to re-contextualizing the core of what ancient classical art can be. This installation includes; a stuffed sash mimicking a philosopher’s toga, seven vibrantly spray painted plaster hands reaching down from the ceiling, one white plaster hand broken apart placed and within the middle of the floor, and numerous multi-colored columns printed and stapled onto the walls surrounding the work. This work rejects the incorrect notion that ancient Greek art is defined by perfectly crafted bodies of untouched white stone, and instead, embraces the camp and “tacky-ness” of the original color palettes in all of their flamboyant glory. This is a pinnacle step toward allowing such art to be lowered from its historical pedestals and made accessible to a larger, more diverse audience. Classical art shouldn’t have to participate in the hierarchy of white classism.

#greek#ancient greek art#ancient greek sculpture#art#installation#scultpure#plasterwork#fibers#fiberart#greek-american#queer#queer artist#queerartwork#moderngreek#artists on tumblr#artwork#SAIC

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

το φυτό | τα φυτά [fiˈtɔ]

=plant

#moderngreek#greek#langbr#polyglot#selftaught#language#language learning#greek words#new words#modern greek

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

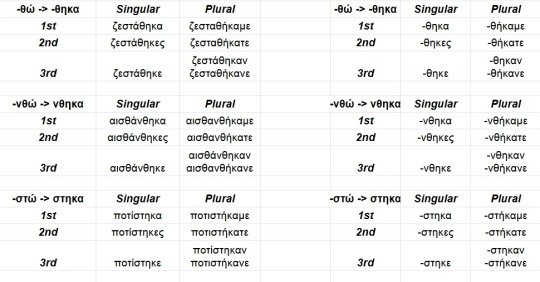

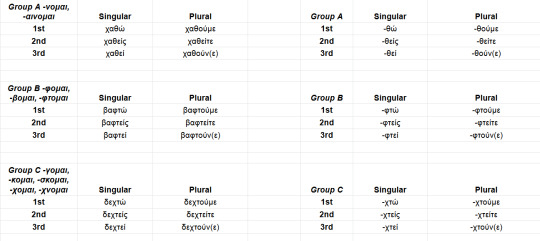

Verbs - The Passive Voice part 4 - Tenses Finale

Finally to complete our section on the Passive Voice verb form tenses before we move on to the moods. In this post we will look at the past tense forms of the Passive Voice verb forms. The Simple Past and the Imperfect(Past Continuous) will have the completely different conjugation forms between the two of them, and while it can be frustrating to have more to form and conjugate, just know we are almost out of the woods as the moods should be relying on previous methods of conjugation, save for the imperative mood. We will first begin with the most drastic change to get the most information out of the way first.

The Simple Past Tense:

To review, this tense is used when we want to describe actions that have taken place in the past and have already been completed in the past. We form this by taking the Future Simple Tense of the Passive Voice, and then we will change the endings as follows:

***please note that this tense will always have the stress accent mark placed on the third syllable from the left***

As shown above, we can see that there are some changes to how the verbs conjugate based off of the verb stems. It may seem like a lot to keep in mind, but fret not. We will go over some things to help us.

1. When the verb in the future simple tense ends in θώ, then we can change it to θηκα and conjugate using the endings in the right hand side of the chart. On the left hand side of the chart is the word ζεσταθώ.

2. When the verb in the future simple tense ends in νθώ, then we can change it to νθηκα and conjugate using the endings in the right hand side of the chart. On the left hand side of the chart is the word αισθανθώ.

3. When the verb in the future simple tense ends in στώ, then we can change it to στηκα and conjugate using the endings in the right hand side of the chart. On the left hand side of the chart is the word ποτιστώ.

4. When the verb in the future simple tense ends in χτώ, then we can change it to χτηκα and conjugate using the endings in the right hand side of the chart. On the left hand side of the chart is the word ανοιχτώ.

5. When the verb in the future simple tense ends in ευτώ, then we can change it to εύτηκα and conjugate using the endings in the right hand side of the chart. On the left hand side of the chart is the word παντρευτώ.

6. When the verb in the future simple tense ends in φτώ, then we can change it to φτηκα and conjugate using the endings in the right hand side of the chart. On the left hand side of the chart is the word γραφτώ.

***To make this feel a little easier to digest, notice that all of the verb conjugations end the same way, by dropping the -ώ and conjugating with -ηκα, -ηκες, -ηκε, -ηκαμε, -ηκατε, -ηκαν/ηκανε.***

Additionally, with words in group 3 such as αγαπιέμαι, λυπάμαι and κοιμάμαι/κοιμούμαι, will change their endings a bit differently from the other verbs shown above.

Easily enough, for all of those endings, we change the ending to ήθηκα and can follow the conjugation table in the chart above on the right hand side.

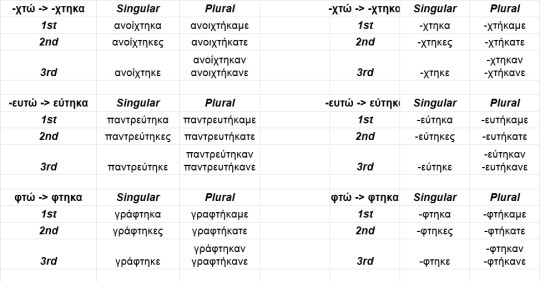

The Past Continuous (Imperfect Tense):

We use this tense when we want to describe an action that was occurring in the past for a duration of time, but no longer does. Comparative to the previous tense, this will be relatively simple, albeit more information to take in mind. We will follow the conjugations in the chart below.

1. Group 1 verbs which end in -ομαι or άμαι will change to -όμουν and follow with the verb endings in the right hand side of the chart for group 1 verbs.

2. Group 2 verbs have endings with -ούμαι and will change to -ούμουν and follow the verb endings in the right hand side of the chart for group 2 verbs.

3. Group 3 verbs which end in ιέμαι will change to -ιόμουν and follow the verb endings in the right hand side of the chart for group 3 verbs.

Lastly, we have,

Past Perfect Tense:

This is another conditional tense in usage. We can use it when we want to describe an action that has happened in the past before another action. We can do this similarly to how we did it with the Active Voice forms. We change the verb to the third person singular future tense form, and throw the past tense of έχω right in front of that.

κοιμάμαι -> θα κοιμηθεί -> είχα κοιμηθεί (I sleep -> he will sleep -> I had slept)

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

That’s all there is to the major conjugations of the Passive Voice Verb forms. Congratulations for navigating through all that with me, and we will begin the next post with a look into the verb moods and how they work with the passive voice verbs and after that we will begin a view into verbs and adjectives.

If you’ve followed along so far, good job! If you haven’t and are just joining us in our journey into Modern Greek grammar, then welcome and take your time, learn and digest the information in a way that makes you feel comfortable. There isn’t a rush to learning.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

I had my chem midterm today and my paper one in modern Greek. I really hope my studying paid off on chemistry because it is my favourite subject and I really want to get a 7! i was studying so much last night and I've solved so many past papers

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

What an amazing dinner last night, a relaxing night out on holiday. If ever you are in Lorne @ipsos_restaurant - delicious modern Greek. We particularly fell in love with the graphics. #coastalholiday #moderngreek https://www.instagram.com/p/CJKxknFjSoS/?igshid=1qar536y4v9k4

0 notes

Photo

2/3 A farewell from the @robinsonclub #ierapetra at the #Mavros beyond the common buffet you have a choice in between three plates with a variety of dishes of a theme, spoiler alert I checked all of them. You can't go wrong with #ModernGreek when in Kreta - #Foodlover #Greece #Travel #souvlaki i #Feta #Pita #Gyros #tzatziki #octopus #mobilephotography (hier: ROBINSON Club Ierapetra) https://www.instagram.com/p/CDZCj7yHIEw/?igshid=661cqcx0ime

#ierapetra#mavros#moderngreek#foodlover#greece#travel#souvlaki#feta#pita#gyros#tzatziki#octopus#mobilephotography

0 notes

Photo

Day 14: What is your favourite Greek food? #SGMChallenge #SpeakGreekInMarch #studymotivation #greek #ελληνικα #ελληνικά #languages #polyglot #studygram #greco #griego #grec #language #languagelearning #linguistics #learngreek #moderngreek

#linguistics#greco#languagelearning#speakgreekinmarch#language#learngreek#ελληνικα#studymotivation#grec#greek#ελληνικά#studygram#languages#polyglot#sgmchallenge#moderngreek#griego

2 notes

·

View notes

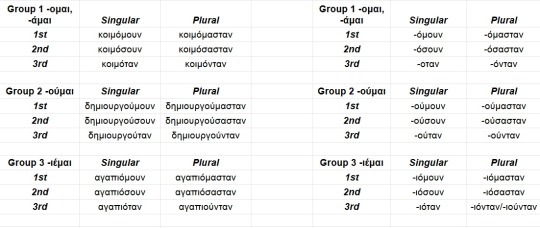

Photo

“There have been many books acting the question, who were the Greeks? ... It is an important question, because just about everything that defines ‘European’ or ‘Western’ culture today, in the arts, sciences, social sciences and politics, has been built upon foundations laid down by the makers of that ancient civilization, whom we also know as ‘Greeks’. Those long-dead Greeks play a part in this story too, but it is not their story. This book begins and ends with the Greek people of today. It explores the ways in which today's Greeks have become who they are, the dilemmas they and generations before them have faced, and the choices that have shaped them subsequently. Above all, this book is about the evolving process of collective identity. In the case of Greeks over the last two centuries, it makes sense to call that identity a national one, since this has been the period that witnessed the creation and consolidation of the Greek nation state.” #currentlyreading #nonfiction #history #bookworm #bookstagram #supportlocallibraries #greece #moderngreeks #twohundredthbirthday

#currentlyreading#nonfiction#history#bookworm#bookstagram#supportlocallibraries#greece#moderngreeks#twohundredthbirthday

0 notes

Text

undefined

youtube

I love food and I love the way she speaks 1st at a normal rate and then very slowly :)

0 notes

Photo

Words are in my not-so-humble opinion, our most inexhaustible source of magic. Capable of both inflicting injury and remedying it - J.K.Rowling

Always loved my words, I am a full blown logophile!!

#moderngreek#greekword#language#words#logophile#logolepsy#wordaddict#wordsarepowerful#meraki#creativity#heartandsoul#essenceofyou

0 notes

Text

Things I Could Do This Summer

- Get back into sewing

- Buy an airbrush kit and learn to turn people into sexy blue aliens

- Write that urban fantasy comedy porn I keep talking about

- Write that definitive Marauders fic I keep talking about

- Learn to make jewelry

- Make a billion paper flowers and throw them into the streets

- Practice piano a lot

- Get shredded. Get an eight-pack.

- Learn to draw

- Learn Spanish/German/ModernGreek/AncientLatin

- Go see all my family members

- ???????????????

- Profit.

1 note

·

View note

Text

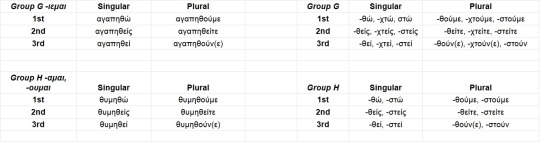

Verbs - The Passive Voice part 2 - Tenses

To continue where we left off, we will be looking at more tenses for the Passive Voice verb forms. I will be adding in some of the explanations for the tenses as they are used, just as was previously explained for the Active Voice forms. Apologies in advance as this will be a long post about most likely, just the simple future tense.

Future Simple Tense(Future Perfect Tense)

This is the verb form that we will be using when an event will occur in the future, and it is an event that has an end. This tense has a lack of habitual recurrence of the action, and once it is completed it is done. Please bear with me, as we will be looking at a few different ways each group of verbs conjugates in this form.

The difference with the Passive verb forms versus the Active verb forms here is that instead of the few groups the active form had, and the changing of the penultimate character, we will be changing a bit more and covering a bit more, and all will be discussed by their groups below the chart(s).

As you can see, there is a lot to unpack here and a chart isn’t the best to try to explain it all on it’s own, so let’s break these down into their parts and sprinkle a few things in to augment our knowledge and understanding.

Group A: These are the passive verb forms that in the present tense had -νομαι or -αίνομαι. These will add the ending -θώ. For the formation of the Simple Future here, is the following:

χάνομαι (I lose myself) -> χά -> θα χαθώ

τρελαίνομαι (I become crazy) -> τρελα -> θα τρελαθώ

We need to take the verb down to a rough portion, and add the new ending while placing the future particle θα in front of the verb (please note that the future particle will be added in every instance of the future tense, and will not be listed in the next group lists, as it will be an assumed step).

*another case I have found in research is that occasionally there will be some of these verbs in group A that will change their ending to -στώ such as πιάνομαι, and will follow the conjugation route for Group F*

Group B: These are the passive verb forms that in the present tense had -φομαι, -βομαι, or -φτομαι. These will add the ending -φτώ. For the formation of the Simple Future here, is the following:

ανταμείβομαι* -> ανταμει -> θα ανταμειφτώ

απαλείφομαι** -> απαλει -> θα απαλειφτώ

σκέφτομαι (I am thinking) -> σκε -> θα σκεφτώ

* (I’m a bit out on the translation for this one, as some dictionaries say it means I am rewarded while others say I exchange)

**(another odd one, as this shows it can be translated as “I am deleted”)

Group C: These are the passive verb forms that in the present tense had -γομαι, -κομαι, -σκομαι, -χομαι or -χνομαι. These will add the ending -χτώ. For the formation of the Simple Future here, is the following:

ξεπετάγομαι (I pop out) -> ξεπετα -> θα ξεπεταχτώ

μπλέκομαι (I get involved/mixed up in) -> μπλε -> θα μπλεχτώ

διδάσκομαι (I am taught) -> διδα -> θα διδαχτώ

υποδέχομαι (I welcome) -> υποδε -> θα υποδεχτώ

ρίχνομαι (I throw myself into) -> ρι -> θα ριχτώ

Group D: These are the passive verb forms that in the present tense had -αίνομαι or -άνομαι. These will add the ending -νθώ. For the formation of the Simple Future here, is the following:

αισθάνομαι (I feel) -> αισθα -> θα αισθανθώ

απολυμπαίνομαι (I disinfect myself) -> απολυμπα -> θα απολυμπανθώ

Group E: These are the passive verb forms that in the present tense had -ευομαι or -ζομαι. These will add the ending -ευτώ, -χτώ, or -στώ. For the formation of the Simple Future here, is the following:

εργάζομαι (I work) -> εργα -> θα εργαστώ

ειδικεύομαι(I specialize) -> ειδικ -> θα ειδιευτώ

*occasionally there may be some verbs ending in -ζομαι that may change to the -χτώ ending*

Group F: These are the passive verb forms that in the present tense had -θομαι. These will add the ending -στώ. For the formation of the Simple Future here, is the following:

πείθομαι (I lose myself) -> χπει -> θα πειστώ

Group G: These are the passive verb forms that in the present tense had -ιεμαι. These will add the ending -θώ, -χτώ, or στώ. For the formation of the Simple Future here, is the following:

Καταριέμαι (I curse) -> καταρ -> θα καταρατώ

Ευχαριστιέμαι (I am glad) -> ευχαριστ -> θα ευχαριστηθώ

Τραβιέμαι (I am pulled/dragged) -> τραβ -> θα τραβηχτώ

*I’ve noticed with this group there is a tendency to change or add a -η- or -α- between the stem and added portion*

and finally,

Group H: These are the passive verb forms that in the present tense had -αμαι or -ουμαι. These will add the ending -θώ, or -στώ. For the formation of the Simple Future here, is the following:

θυμάμαι (I remember) -> θυμ -> θα θυμηθώ

επικαλούμαι (I call upon) -> επικαλ -> θα επικαλεστώ

*to note, there is a trend of adding vowels when a stem is lacking one during conjugation, as always, please research a new word if you are unsure of the conjugation or usage.*

There you have the “simple” future. It really isn’t as complicated as it may seem, there are just a lot of rules to practice, but that means you can try to speak with more people and develop new verbs and conjugation skills. Remember, learning doesn’t have to be a chore and can be a fun recreational thing to do.

Take a breath and relax a little, for the next section I will be finishing the topic of the future tense so that we can continue using the new conjugations that we learned while they are fresh in our heads. Afterwards, I will begin covering the past tense and remainder of the present tense, as by that time we will have seen all the new rules and different forms of conjugations for the passive voice forms.

One more thing to make note of, when I pull verbs, I am using some of the word bank from the list of verbs on Cooljugator.com and bear in mind some verbs, when I check them do not have direct translations, or are not found in some of the dictionaries I reference. The ones I DO find, may not be very commonly used or have a more modern colloquial equivalent that is used on a more frequent basis, so please, take the words with a grain of salt and know that I use them purely because they have value in showing the forms of conjugation and if you are unsure of their use in modern times and are able to, please consult a native speaker. In the future, I will potentially be editing posts with more modern or colloquially used verbs to have more relevant examples.

17 notes

·

View notes