Text

After the Rain and Serious Matters | Mafumafu blog post 2016.01.08

Good evening, Mafumafu here.

As I am writing this blog post, it’s 2am on the 8th of January.

By the time this blog post has been published, I believe the announcement livestream would have already ended.

First I’d like to make an official announcement here, and then talk about something on a more serious note.

I’d really appreciate it if you would read all the way to the end.

Announcement

Serious matters

Announcement

So, after working as Soraru x Mafumafu for 2 years and completing our ATR Live tour,

finally

we have finally decided on a name for our unit!!!

It’s

After the Rain!!

Finally! More like, why didn’t we even have a name for 2 whole years!

Truth be told, we’ve actually been thinking of a name for our unit ever since working on our first song.

But without any sort of reason or preface, just coming right out and saying “So from now on we’ll be working as 〇〇,” would surprise just about anyone.

That’s why at the beginning we just went along without fixing a name.

We didn’t even have a name for our circle, and ended up having a lot of trouble when we had to identify ourselves. Really, it was a lot of trouble.

Starting with our first album, “After Rain Quest”, and completing our first Live Tour, “After the Rain tour 2015”, we decided that we wanted to keep the name that had found a place in our heart.

Thus, we decided on the name After the Rain.

With that said,

2016.4.13

After the Rain will be releasing an album,

『Black crest story』 !!

Yayyyyyyyy!!!

We’re in the midst of production right now, please look forward to it!!

Album details

Release date: 13 April 2016

First-run limited edition CD A (+ tokuten CD) 2500 yen + tax

Tokuten CD will include music tracks (TBA) and Hikikomoranai Radio special edition

First-run limited edition CD B (+ tokuten CD) 2500 yen + tax

Tokuten CD will include a collection of MVs of the listed tracks and footage of live audio recording and interviews

Normal edition 2000 yen + tax

Tokutens available at the following corporations, applicable only to limited edition CDs A&B

Animate: Secret DVD “Soramafu goes to an Onsen” edition

Amazon: B3 poster (of Soramafu themselves)

Tsutaya: TBA music track CD (1 solo song each, total of 2 songs, vocaloid cover ver.)

Tower: TBA music track CD (1 solo song each, total of 2 songs, anisong cover ver.)

WIth that said, I’ve come to the end of the announcement.

Serious Matters

Just writing the announcement already took up more time than expected.

It’s now 3:20am.

I’m sure there are those who are looking forward to what I’m about to say,

and on the other hand there are also those who feel anxious.

So let me start by addressing a few things first.

First of all, as usual, I will still be continuing solo activities as Mafumafu.

I’d like to think of solo x solo activities as a chemical reaction, which makes everything even more fun.

We also did not enter a company or sign any contracts.

We’ll be learning many things again now with a different setting, but I always, always want to treasure this freedom.

In the first place, even if I had the ability to listen to what other people are saying,

I don’t have the cooperativeness and social skills needed to make a decent living. (´-ω-`)

All of our activities will be carried out following our intentions, with the album this time being no exception; everything from production, writing, composing, editing, mixing and mastering, all 100% of it will be completed with our own hands.

The big things that can’t be done individually, I believe they can be accomplished when the two of us combine our powers! We’ll definitely create a wonderful album so please look forward to it ヾ(*´□`*)ノ

To be honest, I was really, really scared of everything and anything.

By experiencing all sorts of pain and sadness, I’ve become the person I am today.

I am someone who can’t really sense another person’s evil intentions, and can be quick to trust people.

Easily swallowing the tales that were told to garner my sympathy, I slowly started hating myself.

I will not disclose the details, but a few years back I was bullied terribly.

It was something made me feel socially, mentally and physically pressured.

Being woken up in the middle of the night by the door being kicked open, or being shouted at,

being dragged out while still in my pajamas, or just having insults hurled at me.

After doing some investigation, I learned that I, as well as a group of people, have been cheated by someone, and it seemed that they had the intention of sowing discord amongst us.

Now, I’ve already made up with that group, and we treat that incident as a joke, but at that time it was really painful, depressing, and scary.

Unable to overcome a part of this incident, wrecked by the spite and violence,

swallowed by despair, the one who reached out his hand to me was Soraru-san.

Soraru-san, who found out about the truth, defended me and made the culprit promise “Not to do anything to hurt Mafumafu again”.

He also said that he’d always look out for me, and thanks to soraru-san, I was able to find release.

Urata-san, Amatsuki-kun, luz-kun, all these friends were also there for me when I needed someone to talk to.

And after packing my stuff, and moving…

Just thinking that if things were left alone is enough to send shudders down my spine.

“What the hell is that? A story from some manga?” might be what you’re thinking right now, but this is all true.

In fact, all of this doesn’t even amount to a fraction of the whole incident.

With all these things happening, I started working together with Soraru-san.

I feel like it’ll come off as too staged if I were to praise this friend of mine right now,

so I won’t praise him, but just let me say that I’m utterly grateful to him.

Without knowing, it seems like I’ve told an unbelievable story, so it’s no surprise that I have such a gloomy personality right!?

It seems like I’m still trying to justify my gloomy personality. I seriously don’t know when to give up do I!

Being cheerful and having fun is still the best huh~_( _ `ω、)_

Our two albums After Rain Quest and Prism Ark,

as well as our ATR tour, have gotten amazing response.

Makes me nervous.

Being so afraid of dying to the point of nearing death and having had my head trapped in an endless cycle of pain,

I transformed all these thoughts into songs and lyrics, which so many people hear today.

I can’t help but cower in fear under the eyes of others, to the point where I can’t even take the train,

yet I was able to stand on that stage, look forward and smile.

Last year was a peaceful year and I was able to devote a lot of my time to music.

I don’t really know how to put this into words, but I’m really happy that there are people out there who can accept the person that I am today.

I’m really grateful.

Right now it’s 5am in the morning.

Just how long am I gonna take to write this…

I’m writing this while being in a state of half-sleep so maybe all this is just an incoherent mess? Will it be okay?

In any case, whatever I write will end up becoming a really formal essay right

I tried my best to write it in a lighter tone but well

It’s gonna be hard to read….(´・ω・`)

Now then

My activities as Mafumafu, as After the Rain, as a composer,

whichever it may be, I’ll definitely create more good music in 2016.

I’ll write till I’ve written out everything I wanted to say.

I want to have the most fun when doing lots of fun things.

What even is a composer

I kinda have an inkling as to what it is but please make a guess

So long wwwwwwwwww

wtf is this wwwwwwww I feel like someone who suffers from some communication disorder when they can’t stop talking wwwwwww

Thanks for reading all the way till here www

From now on it’ll be busy again but I’ll give it my all! Goodnight! ヾ(*´ー`*)ノ

(t/n: really really grateful that mafu had the courage to come out and tell us about his past, his story, and it just shows how far he’s come as a person, how he’s grown, how important ATR is to him and how much Soraru means to him, how much he has saved him, and I’m really really glad they’re friends today. and mafu is a precious angel. congratulations on their major debut as After the Rain, congratulations to a lasting partnership, congratulations to mafu for being brave, to soraru for his courage to save mafu and I’m really super happy!!!!

side note first time translating one of mafu’s blog posts and it’s one of the longest and probably is BUT thanks for reading!! kinda gave up halfway cos mafu also kinda gave up talking coherently so what’s a coherent translation man

once again congratulations to soramafu!!!!!! ^^)

also first song of ATR!! check it out here

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

LMAOOO

(i hope we all agree the best revenge plan ever is nie huaisang’s)

On a scale from Eren Jaegar to the Count of Mount Cristo, how good is your revenge plan?

438 notes

·

View notes

Text

:(

Japanese author Osamu Dazai giving a lecture at Tokyo University of Commerce (the predecessor of the current Hitotsubashi University) entitled 'Modern Diseases' on October 2 1940.

Fun Fact: Dazai was nervous and sweaty on this day, his friends recalled him being extremely nervous, wiping his forehead with a handkerchief.

The lecture was a success though, and his popularity grew among the students with many of them starting to enthusiastically read his work.

241 notes

·

View notes

Text

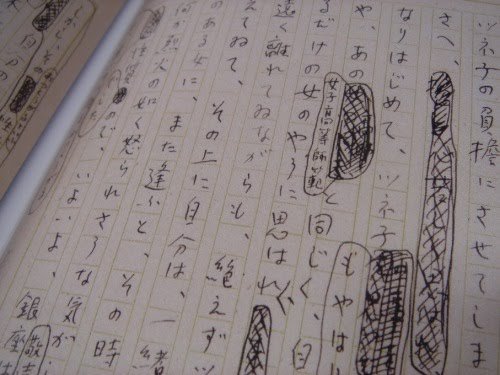

Manuscript of No Longer Human by Japanese author Osamu Dazai

711 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sign of the Times: Akutagawa Ryūnosuke and Taishō Era Literature

Sign of the Times: Akutagawa Ryūnosuke and Taishō Era Literature

This served as the introduction to my thesis, and it makes a good starting point for Akutagawa, I think. This is my way of saying that I already wrote a whole lot about why Akutagawa is important and I don’t want to do it again.

I do not wish to remove the inline citations, also known as the worst kind of citations, so you can ponder over whether Yu or Ueda was a better source.

***

Japan was in a state of turmoil when Emperor Meiji took the throne at the young age of sixteen in 1868. Twenty years before then, Commodore Perry’s mission to open up Japanese trade to the west—by force, if necessary—had broken over two hundred years of self-imposed isolation. Japan found itself on the end of unequal treaties dictated by American diplomats, and it appeared as those Japan would join most of Asia in being colonized by Western powers. During his forty-year reign, however, Meiji oversaw a massive modernization of the country politically, economically, militarily and culturally. By the time of his death in 1912, Japan had undergone a technological revolution, reversed its unequal treaties, bested China and Russia in war and even claimed its own colony, Korea (Sims 2, 17-8, 69, 93).

Meiji’s grandson Shōwa (Hirohito) ruled, as both regent and emperor, for almost seventy years. He saw Japan through its empire building in the 1920s and 30s and through success and defeat in, as it is called in Japan, the Fifteen Years’ War. As a cultural figurehead, he oversaw the trials and rebuilding of occupation, the ascendant economy of the 1960s and 70s, and died in 1989 with Japan as a major world power (Bix 5, 13, 16). These two emperors together saw Japan through over a century of massive political upheavals, beginning with a feudal system largely unchanged since the 1600s and ending with a modern democracy (Sims 1-2). Their presence and drive shaped Japan’s modernization, wartime, and rebuilding.

However, the leadership in between these two strong rulers was found wanting. Emperor Taishō, son of Meiji and father of Shōwa, ruled for a mere fourteen years, and in name only for the last five. His son acted as regent for the rarely-seen emperor (Bix 93). Bereft of charisma, Taishō was an ineffective leader and lacked the strong guiding touch of his father and son. While Meiji had rejected the traditional role of the unseen emperor by making public appearances and official visits, Taishō was confined to the Imperial Palace (Sims 17-8, Bix 53). The genrō, the elder statesmen of the Meiji era, intended to use the instability following the death of Emperor Meiji to enact laws and edicts favoring themselves, but the public saw through this plot and political parties overthrew the genrō as the primary force in Japanese politics (Sims 106-7). Without a strong imperial influence from either the emperor himself or his advisors, society and culture proceeded in a more liberal direction. This era has been called the “Taishō Democracy,” but this liberalization also extended to the arts. Communism and socialism gained popularity alongside naturalism, social realism, “Dekanshō” (the works of Descartes, Kant, and Schopenhauer) (Jansen 540), and a gothic style called “erotic, grotesque nonsense.” A campaign of poorly executed strike-busting led to citizens favoring workers over the military (Bix 52-3). Japanese workers celebrated their first May Day in 1920, the Japanese Communist Party was formed in 1922 (Putzar and Hisamatsu 200-1), and the Imperial Diet approved universal male suffrage in 1925 (Yu 47). Literature and culture thrived in this transiently permissive atmosphere.

Though Akutagawa Ryūnosuke was a member of this generation of Taishō writers, in many ways he was everything they were not. Works such as “The Monkey and the Crab” (Sarukani-kassen) and “Peach Boy” (Momotarō) could not have been written by any of Akutagawa’s contemporaries. Though these stories had one eye on present-day society, they were still too rooted in traditional Japan. They were too ironic and too satirical for the naturalists, and though they expressed awareness of the lower classes, they were not concerned enough with the struggle of everyday life for the Marxists (Rimer 142). Unlike many of the other writers who came of age in the Taishō era, Akutagawa, though he sympathized with their causes, had little patience for either proletariat literature or naturalism (Yu 49).

Japanese naturalism was commonly expressed through the shishōusetsu, or the “I Novel” (Putzar and Hisamatsu 187). These novels were primarily based around thinly-veiled fictionalizations of shameful events in an author’s life. Akutagawa, for most of his career, deliberately avoided writing about his own life and experiences. He claimed later in life that his first stories were written to try and take his mind off of a badly ended relationship (Keene 558). Akutagawa believed that to write too honestly about his own experiences would leave his own life, rather than his stories, open to criticism. This, he intimated, was something he would be unable to bear (Tsuruta 24). As a result, even in his final, troubled years, when his writings were marked by deeply personal explorations of his own life and psyche, Akutagawa maintained a veneer of fiction on his short stories. He never relied on the confessional style practiced by many of his fellow authors (Yamanouchi 92).

Those same worries and fears that eventually drove Akutagawa to suicide were born shortly after he was. The signs of the Chinese zodiac are not limited to years: the month, the day of the week, and the hour also have a representative animal. And Akutagawa Ryūnosuke, “Son of the Dragon,” was born in the year and the month and the day and the hour of the dragon (Shaw i). Born to parents of rather advanced age, he was given to a wet nurse instead of his mother (Yu 7). When he was less than a year old his mother became insane and he was adopted by his mother’s sister, effectively destroying his relationship with both his father and his mother. His mother died, still suffering from insanity, when he was eleven (Yamanouchi 88). This fear of insanity haunted Akutagawa all his life; at the time, insanity was believed to be a hereditary condition (Keene 557). Akutagawa began publishing in literary magazines while still a student at Tokyō Imperial University, and one of his early successes, “Hana” (The Nose) earned praise from veteran Meiji era author Sōseki Natsume for containing three elements missing from I Novels: humor, novelty, and brevity (Tsuruta 22). Afterwards, he carried himself as the elder author’s disciple. Sōseki gave the young writer some advice that apparently stuck: ignore what everybody else is writing about (Yu 16). In 1919, he resigned his position as a professor of English at the Yokosuka Naval Engineering School (to the benefit of the navy, he joked) in order to become a full-time writer (Hibbett, “Negative Ideal” 439).

Contemporaries of Akutagawa both applauded and lambasted him for favoring style over substance. His critics called his works “detached” (Yu 18), “artificial…” (Ueda 137) and said that he was too clever for his own good (Hibbett, “Introduction” 11). His works, they said, were very consciously works; they were too deliberate to be stories. Akutagawa’s writing was filled with perfectly formed phrases, but the accuracy of his phrasing destroyed any sense of spontaneity (Ueda 137). Akutagawa found this to be a foolish and pretentious criticism; nobody, he said could write a story on accident (Ueda 18-19). More irritating for Akutagawa would have been the claims that he was too stylistic, claims which he dismissed at first. In Akutagawa’s mind, content and form were inseparable. He considered writing that was too skillful, too stylistic, to be antithetical to art (Yu 19). Later in his life, Akutagawa himself would wonder if his deftness was not holding back his writing ability. Speaking of the work of other writers as well as his own lesser stories, he said, “It is easy to cover a lack of sincerity with skill” (qtd. in Cavanaugh 53).

A more oft-noted contention, however, was the issue of Akutagawa’s originality. Akutagawa famously relied on a diverse number of sources from various times and places. Nearly half of his 150 short stories are dependent on other works, ranging, as Yu puts it, “from mere inspiration to outright plagiarism” (21). However, even Akutagawa’s plagiarism was not as simple as it might appear. The basic plot points of his short story “Rashōmon,” for example, are largely drawn from a single story from the Konjaku monogatari (Stories from Long Ago), an anthology of tales about a thousand years old. However, the story, just a few pages long, incorporates elements of a few other tales in that collection as well as medical details Akutagawa gleaned from his university lectures (Yamanouchi 89). And of course, the analysis of the protagonist’s psyche is all Akutagawa’s original work. Yu provides another example in “Kumo no ito” (The Spider’s Thread). This story, dripping with Buddhist symbolism and imagery, is actually an adaptation of a Christian parable which appears in The Brothers Karamazov (25). Akutagawa, for his part, claimed that his use of disparate elements was pragmatic: a story needs an unusual incident, and an audience is more willing to accept an unusual incident in an equally unusual or unrealistic setting (qtd. in Keene 559-60).

Akutagawa’s strategy is readily apparent in this collection. Three of the four short stories are, like much of Akutagawa’s output, based on prior sources. In this case, they are each based on popular Japanese fairy tales. Just as Akutagawa’s early work relied on the Konjaku monogatari, his “middle period” of 1920 to 1924 often incorporated fairy tales and traditional stories from both inside and outside Japan (Yu 51). However, Akutagawa stretches the limits of the fairy tale format in these stories, as he did with his works based on the Konjaku monogatari, by using them to explore contemporary themes, keeping one eye on the past and one eye on the present (Putzar and Hisamatsu 194). He uses the fairy tale format to explore the gap between a uniquely Japanese past and a present in which the Japanese arts exists alongside—or opposing—Western culture.

As Taishō era authors took prominence, some of the old guard of Meiji writers grew concerned with authors’ increasing focus on Western-style literature at the expense of Japanese-style works (Chance 145). Akutagawa differed from his Taishō contemporaries in that regard: he sympathized with the authors of the Meiji era, such as Mori Ogai and Sōseki. Because Akutagawa, like Mori and Sōseki, was extremely well-versed in Western literature, he was more willing to be critical of it (Putzar and Hisamatsu 192). Whereas most writers of Akutagawa’s generation embraced Western literature and culture, Akutugawa, like his literary heroes, always perceived even his favorite aspects of Western culture to be fundamentally different and alien. This theme would dominate Akutagawa’s writing in the last years of his life (Dodd 194).

Akutagawa’s output in his final years explored his childhood as well as his anxieties about the modern age. Death increasingly took the forefront in Akutagawa’s later period works. In one, he details the lives and deaths of all of his immediate family, including a sister who had died before he was born. The death of his sister’s husband appears in two separate stories. However, true to form, he continued to fictionalize some details of his actual life experiences: one is told entirely in the third-person; he exaggerates the (what can only loosely be called) poverty of his childhood, and, in one of those stories featuring his brother-in-law’s death, he omits the fact that the man, suspected of arson, had thrown himself under a train. Many of these stories were published posthumously, and one, “The Life of a Fool” was entrusted to his friend, the author Kume Masao. Akutagawa gave Kume the responsibility of deciding whether or not it was worth publishing. Akutagawa’s suicide note, written a month later, was also addressed to Kume (Akutagawa, “Isshō”).

Emperor Taishō died on Christmas Day, 1926 and Akutagawa took a fatal overdose of sleeping medication seven months later. In the coming few years the Taishō Democracy came to an ignoble end, as liberalism and permissiveness were crushed by worldwide economic depression and the military machine. Akutagawa cited the reason for his suicide as being a “vague unease about (his) own future” (Akutagawa, “Shuki”), and, looking at the course of the next few years, it is hard to deny that it seems prophetic. Akutagawa was no stranger to censorship; his short story “Shōgun” (The General) was targeted by government censors for its unpatriotic, satirical and critical portrait of the war here Nogi Maresuke (Arita). However, it is unlikely that the author would have continued to get off so likely. The same riots that had demonized the army in the eyes of the public in the early Taishō years had inspired the top brass to take measures against liberal movements (Sims 123). In 1928, the year after Akutagawa’s death, police began rounding up suspected political leftists under the auspices of the Peace Preservation Law. Fifteen long years of war began with a false-flag attack in Mukden, China, that served to justify an invasion of Manchuria in 1931. Leading proletariat author Kobayashi Takiji was tortured to death by special police forces in 1933 (Rubin 232). The main character of “Momotarō,” the fairy tale upon which Akutagawa based his blistering anti-war satire of the same name, became a symbol for Japan’s power projected overseas (Tierney 117-8). For those authors who cut their teeth during the comparatively permissive Taishō Democracy, the war years of the early Shōwa period would have been almost unrecognizable.

Critics have debated whether Akutagawa’s suicide was born out of the author’s failed attempt to forge a new, more personal style with his late career turn, an inability to blend his prose with the leftist politics he supported, the only logical course of action for a man who declared that literature was more important than life itself, or nothing more than the product of a tortured soul. However, it is only natural that Akutagawa would go out so soon after the end of the Taishō era. The new style that Akutagawa was on the verge of mastering was cut short as much by the emperor’s death as by his own. Akutagawa’s career followed the course of the Taishō era particularly well: Taishō’s reign and Akutagawa’s career began and ended within a year of each other, and Akutagawa symbolizes Taishō literature to such an extent that it is his death, rather than the era’s namesake, that traditionally rings the literary era to a close (Lippit 28). Akutagawa flourished in that short period when Western novels were in vogue yet still new enough to be strange, in the period between the censorship of the Meiji era and the oppression of the early Shōwa period. Most of Akutagawa’s best stories required nothing more than good material for inspiration, and so it is fortunate that one of Japan’s most fruitful authors happened to be planted in some of history’s richest soil.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

here we areeeeee

just a coincidence my game copy crashed and damaged JUST AFTER THAT SCENE and now i have to REDOWNLOAD IT and START IT FUCKING OVER. well you don’t even want me to see that scum boy dont’you? got it, I have to agree

kawase my boy i’m coming to you again

The amount of hate I have for Hanazawa is huge. I’d pick Kawase a million times over this guy. I feel nothing but disgust. That smut scene made me physically ill. Easily the WORST route in the entire game. FUCK THIS GUY.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

OMFG i just realized even the hashihime quartet tamamori-kawase-minakami-hanazawa IS from Aizu too. LMAO aizu best historical bl city ever

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

quello che ho scoperto sul contesto storico di Hybrid Child perché ho voglia di rantare: (A Hybrid Child’s historical setting theory. eventually a brief summary in perhaps bad english will follow. just for fun)

siccome hybrid child occupa un posto specialissimo nel mio cuore e non so neanche bene perché, ogni tanto mi diverto a fare qualche ricerca per capire se l’ambientazione è completamente frutto di fantasia o, visto che soprattutto la vicenda degli ultimi due capitoli (leggi: oav) si svolge in un periodo storico ben preciso, se invece presenta più elementi storicamente verosimili. io non ho alcuna preparazione in merito (sigh vorrei), semplicemente mi intriga mega quel periodo di sommosse casini riforme prima della restaurazione di meiji; quindi, fonti: wikipedia e qualche blog. ho letto anche i capitoli di due libri di storia giapponese sull’argomento ma sono stati completamente inutili lmao.

cos’ho scoperto quindi? partiamo con ordine. le cose che si sanno esplicitamente dalla storia: si sa che quando l’idillio spensierato dei tre dell’ave maria crasha è perché lo shōgun se ne è scappato via, quindi il loro feudo è bollato come fazione ribelle. sappiamo anche che l’imperatore, ormai tornato sul pezzo, si era impadronito del castello di Edo e ora stava andando a fare il culo al loro clan. allego prove:

il giappone in quel periodo era una militocrazia, dove il potere esecutivo era completamente nelle mani dei generali, gli shōgun. appunto per questo motivo il governo viene chiamato shōgunato o, in giapponese, bakufu (governo delle tenda. non mi ricordo perché). fatto sta che l’imperatore nel corso dei decenni aveva perso sempre di più il proprio potere effettivo, rivestendo poco più che una carica formale, dato che il governo era tutto in mano all’esercito. al di sotto dello shōgun c’erano i vari daimyō, ovvero i signori feudali di ogni rispettivo clan (han) che ricevevano le terre dallo shōgun e a loro volta le distribuivano ai samurai loro sottoposti. tra di essi, alcuni venivano scelti come ministri/vassalli e i più importanti erano i karō, che rispondevano direttamente al signore feudale; generalmente c’era un karō che stava a Edo dove c’era lo shōgun e un altro che rimaneva a fare la guardia al castello del feudo. da HC sappiamo che non siamo a Edo, ergo Tsukishima doveva essere il ministro che restava a casa e infatti era nei dintorni del castello (quando non era a casa di Kuroda o in giro a mangiarsi dolcetti *cough*).

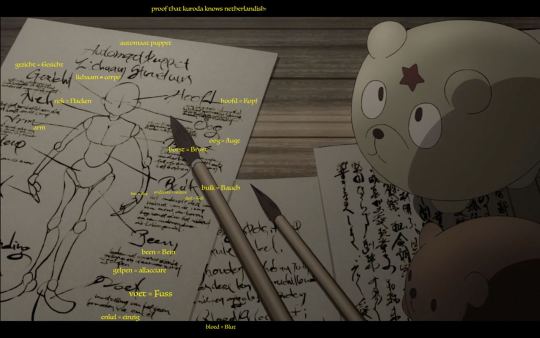

quando cade il regime feudale aka lo shōgunato? quando guarda caso lo shōgun allora in carica, tale Tokugawa Yoshinobu, abdica! perché convinto/costretto dall’imperatore che si è fatto come alleati due dei clan grossi sostenitori del bakufu che non sopportano più la mollezza delle riforme shogunali e vogliono un Giappone fedele all’imperatore e pronto a espellere gli i barbari occidentali che premono per farlo uscire dal sakoku (chiusura blindata del Paese) that means: nessuno entra, nessuno esce e nessuno può essere cristiano o imparare una lingua straniera, tie’. solo nel tardo periodo Tokugawa si era giunti al compromesso di accettare solo gli olandesi e di permettere a qualunque giapponese, non solo agli interpreti diplomatici, di imparare l’olandese. perché questa precisazione? perché, fun fact, i documenti che si vedono nell’anime quando Kuroda smanetta con gli hybrid child sono in olandese! lol (allego prova di quando mi sono messa a decifrarlo solo in base ale mie conoscenze del tedesco)

comunque, lo shōgun prima di arrendersi del tutto prova a scappare a Kyōto perché è incoraggiato dal clan Aizu ma durante lo scontro armato contro le truppe imperiali si accorge di essere troppo debole, lascia capra e cavoli (dove i cavoli sono del suo esercito) e fugge a Edo. viene raggiunto dall’imperatore, si arrende, chiede di essere risparmiato e messo in prigione e praticamente concede all’imperatore di appropriarsi del castello di Edo. direi che fin qui tutto combacia: siamo nel 1868, gli imperiali sono a Edo e si stanno dirigendo a sottomettere anche gli ultimi clan che, ora che non c’è più uno shōgun, sono automaticamente considerati dei riottosi nemici pubblici. è l’inizio del bakumatsu (fine del bakufu) e della restaurazione imperiale che procederà fino alla salita al trono dell’imperatore Mutsuhito (futuro Meiji) inaugurando così una nuova e complicatissima epoca della storia nipponica.

ma torniamo ai gays. il momento della convocazione effettiva alle armi coincide con quello in cui viene spiegata la strategia di attacco del nemico:

Kazusa, Utsunomiya e Dewa erano tre province storicamente esistite che coprivano alcuni territori a nord di Edo. E la traiettoria ipotizzata dell’invasione combacia ancora una volta con il percorso che viene mostrato nell’anime. Se ne deduce quindi che, siccome il clan dei nostri eroi si caga sotto per l’avanzata dei lealisti all’imperatore, la sede del feudo sia per forza di cose a nord di Edo e vicino ai territori menzionati. Skippo la parte successiva sulla strategia di Tsukishima che assegna i comandanti alle città/zone, perché stranamente non credo siano toponimi storicamente accurati, non ho trovato nessuna conferma al riguardo.

avevamo detto che Yoshinobu aveva ripreso a lottare contro l’imperatore perché incoraggiato dal dominio Aizu. Ecco, la mia ipotesi è proprio che il clan di cui si parla in HC sia (fortemente ispirato a) Aizu. Perché?

1. era conosciuto per la qualità e il valore dei suoi samurai (speaks for itself)

2. era stato uno dei maggiori alleati dello shōgun e, in seguito al tradimento dei clan Satsuma e Chōshū che erano passati dalla parte dell’imperatore costringendo lo shōgun a fare altrettanto, è stato considerato da annientare in quanto ribelle.

3. è passato alla storia per una battaglia molto feroce e sentita che aveva come obiettivo quella di costringere il feudo alla resa o scioglierlo, in cui sparavano non stop al castello. e che ovviamente è stata persa e come conseguenza ha portato alla resa di Aizu-han e alla deportazione dei suoi samurai superstiti.

4. la posizione combacia con la possibile ubicazione della città di HC, ovvero: l’odierna Fukushima, appena più a nord di Utsunomiya e perfettamente circondata dalle altre province verso cui gli imperiali erano diretti.

5. il castello di Aizuwakamatsu, noto come castello di Tsuruga, looks like this:

^ aizuwakamatsu’s castle ^ hybrid child’s castle

be’ direi.. no doubts about it. questo castello è stato gravemente danneggiato durante la battaglia di Aizu dell’ottobre 1868, ed è stato ricostruito solo nel Novecento inoltrato. Nello specifico, le cronache dicono che era stato danneggiato senza sosta da palle di cannone che venivano agevolmente sparate da un’altura montagnosa che sorge proprio di fronte al castello.

again:

c’è una montagnetta della stessa altezza del castello raffigurata sulla cartina che combacia proprio con la prospettiva in primo piano dell’immagine da cui presumibilmente venivano le cannonate.

QUINDI RIASSUMENDO SÌ I KUROSHIMA SONO DI AIZU POSSO MORIRE FELICE ORA CHE L’HO SCOPERTO

-

english summary: my task on HC’s historical setting is that Tsukishima’s clan is very likely to be Aizu domain. Because Aizu clan was one of the most loyal shogunate supporter, and after the shōgun surrendered himself to the new-restored emperor and handed him Edo castle, this feud found itself abandoned and marked as rebellious. Thus the imperials started a fight in Aizu (october 1868), which is a land renown for its famous castle, and after a hard battle the Aizu people lost, the clan was dissolved and the castle burnt down. The toponymies mentioned in the HC story match the actually existed ancient provinces in late Edo Japan, and the location of them too fits the position on the map that Tsukishima displays. Aizu itself used to be in the now-called Fukushima prefecture, north of Tōkyō. And pls look at the castle it is THAT castle. undoubtedly.

#hybrid child#rant#historical#context#setting#ce l'ho fatta a finirlo#ecco cosa faccio quando mi annoio#bored as hell i guess#hope someone is interested#japanese history#theory#tsukishima#kuroda#i'm painting without t#aizu#han#castle#domain#1868#no proof but 100% sure#bakufu#bakumatsu#shogun#edo period

1 note

·

View note

Photo

what is it with overprotective big brothers and their tendency to lose their heads 🤔

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

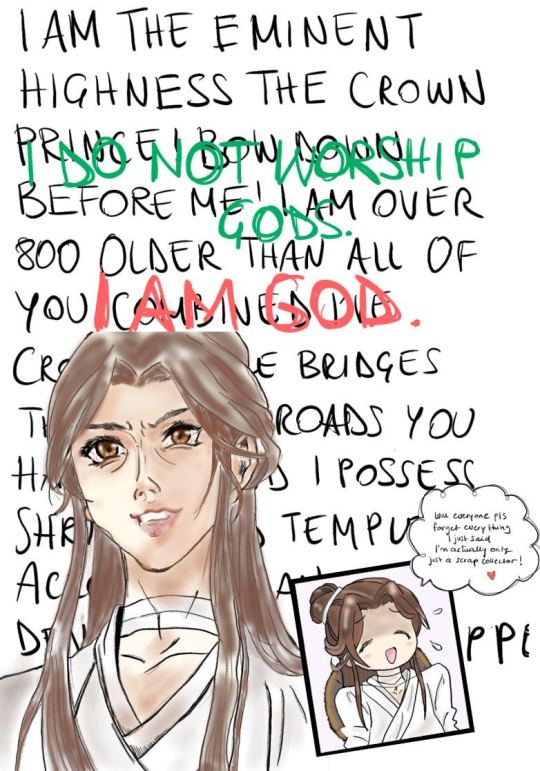

One of my fav hilarious scene of the novel. Cried my ass out

#tian guan ci fu#Tgcf#Novel#Xie Lian#Taizi Dianxia#Dianxia#Killer meatballs#Pls dianxia cook for me so I can die#I'm gonna cook for your cousin#heaven official's blessing

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

would you believe a man says this because he’s mad about his house getting knocked down and he needs to sufficiently stun everyone so he can fling his toxic meatballs into their mouths in order to stop one of his colleagues from strangling his other colleague

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

My fav foxy eyes

#mdzs#mo dao zu shi#donghua#Jin GuangYao#Meng Yao#A-Yao#The handsomest ever#Lianfang-zun#I can't digital art#I'm using gimp#With a mouseless pc

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Modern AU Xue Yang is a tongue piercer can't change my mind

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

reblog and put in the tags what your favorite fictional characters have in common

#Laziness#Not knowing a thing#Love for art and birds#Fake smiles and fake malaise#Own personal space#Isfp mbti lol#Awkwardness more than 99999#Sincerely hate doing adults and work-related stuff#Chilling#Anxiety#Would give their everything to succeed in finally not doing anything at all#WHAT IF I do want TO BE A GOOD FOR NOTHING??#Lost all past friendship and ended up alone#Let others do the dirty job#Always calm and sleepy#Sweating#Afraid of fucking every thing#(well this last one suits A-Yao too)

20K notes

·

View notes

Text

Wretched beginning

Wretched end

#tgcf#Tian guan ci fu#heaven's official blessing#Wind Master#shi qingxuan#Sqx#beefleaf#Leaf without beef#OC

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tbh I'd buy jgy's hat to wear it inside my room while playing acnh. I kinda like this combo it gives me powerful vibes

#Thought of the day#Jiggy's hat#If only HuaiSang hadn't take it away for himself (and to do what I don't even want to know)#Maybe it does exist in cosplay clothes?#I want it so bad#And also my birthday is near

1 note

·

View note