#Even thinking for oneself is seen as alien and incomprehensible

Text

Weird idea but hear me out.

Lostbelt King Florence Nightingale that’s been pushed even further into madness than her Berserker incarnation. She has made a world where death as a concept no longer exists.

This is not a good thing.

#fate#fate grand order#fgo#florence nightingale#imagine a Lostbelt that’s a horrific hybrid of I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream and Bioshock#A land where humanity has reached a ‘perfected’ state where no one can die#But at the cost of everyone’s humanity#As an inverse to Berserker Nightingale sacrificing her own humanity for the sake of her dream#Lostbelt King Nightingale sacrificed everyone else’s#Coming with the side effect that#Like Qin Shi Huang’s Lostbelt#The concept of heroes is completely foreign to this faceless and broken humanity#Even thinking for oneself is seen as alien and incomprehensible#Thanks to all the changes Lostbelt Nightingale has done#This may or not be heavily inspired by 300IQPrower’s own Lostbelt concepts#Which you should totally check out

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anonymous asked: I really enjoyed your book review of Sebastian Junger’s Homecoming. Perhaps enjoyment isn’t the right word because it brought home some hard truths. Your book review really helped me understand my older brother better when I think back on how he came home from the war in Afghanistan after serving with the Paras and had medals pinned up the yin yang. It was hard on everyone in the family, especially for him and his wife and young kids. He has found it hard going. Thanks for sharing your own thoughts as a combat veteran from that war. Even if you’re a toff you don’t come across as a typical Oxbridge poncey Rupert! As you’re a classicist and historian how did ancient soldiers deal with PTSD? Did the Greeks and Roman soldiers even suffer from it like our fighting boys and girls do? Is PTSD just a modern thing?

See previous post for Part 1. Part 2 of my answer here below....

But does it mean no Greek or Roman soldier ever suffered trauma or mental illness? Is there nothing we can’t learn from them? Of course not. Both the Greeks and Romans can teach us a lot about suffering.

Both cultures recognised the importance of integrating soldiers back into society that were they had tried to defend on the battlefield. And I think we can learn a lot from them in the regard.

If we are able to accept that PTSD is not a product of mechanised warfare and very likely did occur in ancient societies, then the question should be asked: how did ancient cultures deal with individuals who experienced trauma and suffering? We know that exposure to violence occurred. And we know, too, that homecoming was a common experience, in that some type of military service was a regular feature of the cursus honorum for those in the senatorial class and was an avenue for the lower classes seeking advancement. Valour in combat was respected, and it was not unusual, when in pursuit of higher office or defending oneself at trial, to display one’s scars from battle as a physical witness of character.

Inscriptions inform us that many veterans pursued successful careers upon their return, becoming leading men in their cities. We know that they feared war and respected it, we know that they used ritual to distinguish war from peace, but we do not know how these men fared emotionally and psychologically after long exposure to violence.

While many ancient cultures were able to recognise the significant changes in soldiers following a battle, the precise reasons as to what created these changes were elusive. A common explanation was that the occurrence of (what I describe as) PTSD was caused by the actions of malevolent ghosts or spirits of those who were killed in battle and now sought vengeance on their killer. While it is unlikely that a vengeful spirit explanation is correct, it does contain the insight that the sickness originated from an inward or unseeable wounding, and these invisible wounds could be just as deadly as any outward wound.

Many ancient cultures sought to deal with and create specific rituals to heal the unseeable and drive off the ghosts who caused them. The central purpose of these often culturally unique rituals was to welcome the returning soldier back into society and allow for the release of trauma. The Romans directed the Vestal Virgins to bathe returning soldiers, purging them of the corruption of war.

While the plethora of writings describing PTSD-like signs in ancient veterans indicate that these rituals did not always work, given the sheer numbers of ancient soldiers who went into battle and through these rituals, it would seem likely that for many something about them did work. However, it might not have been the welcome back into society alone that worked.

What might have been even more important, and what is often overlooked, was that the reintegration process would begin in the aftermath of the battle when the survivors began to walk home. Given that ancient soldiers sometimes fought far from their homeland, when the war was over they had to the walk home. The speed of this return was dictated by the pace of the slowest pack animals and the slow pace, while frustrating, may well have given the soldiers much needed time to reflect upon what they had experienced, grieve for comrades lost and perhaps find solace in a shared group experience. The long march back culminated in a ritual cleansing and a return to home, as mentioned above.

One of the reasons this slow decompression might have aided the efficacy of the return rituals can be seen in its complete opposite in contemporary conflict, where the advent of improved transport has made it possible to move troops quickly and efficiently. Perhaps too quickly and too efficiently. While troops might be happy to be back at home far more quickly, there might be a lost opportunity for soldiers to properly process what they have seen and experienced within a like-minded group.

I believe that we must be cautious when we map the past too neatly upon our own experiences or, conversely, our own experiences too neatly upon the past. While there are similarities and continuities, the relationship between ancient and modern must be carefully parsed. All lovers of the classical past are familiar with how the study of the Greeks and Romans awakens profound and contradictory feelings of identification and alienation. With respect to combat trauma, the shock felt by a modern soldier upon seeing a corpse for the first time would have been incomprehensible to both the Greeks and the Romans, who were surrounded by death.

Likewise, modern technology – with its distant, impersonal, and terrifyingly effective weapons, its instantaneous communication between home front and front line, and the speed of return from combat – requires an adaptability and an ability to get one’s head around big spaces and multiple actors that would never have been demanded from a Roman legionary.

My own view is that our soldiers actually face more complicated psychological factors than did the Romans – including a populace that largely avoids the realities of war while still wishing to enjoy the profits of it.

In addition, as our understanding of what causes PTSD grows we may find a paradox: distance weapons, developed to provide overwhelming military superiority and to shield troops from the fear and horror of close combat, may in fact cause more trauma, whether owing to the shockwaves they send through the brain or to the sense of helplessness they engender.

Moreover psychologists believe that modern PTSD cases are the result of the loss of ‘ontological security’ – ‘an individual’s inability to reconcile their traumatic memories with their moral codes, self-concepts, beliefs about human nature and notions of cosmic justice through which they seek to impose what anthropologists call a sense of order and meaning on the world. The psychological conflict arising from trauma ensures that the trauma lives on as ‘a source of socially and psychologically maladaptive behaviour’. But - and here’s the crux of it - the definition of what is a traumatic memory is as variable as the sufferer is individual, and this is culturally dependent even in the most homogenous societies.

Where we can learn from the Greeks and Romans is how they dealt with homecoming and using religious spirituality to balm emotional wounds.

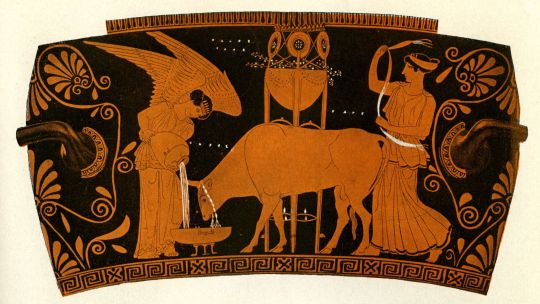

For the Greek warrior, Classical Greek culture, like that of Rome after them, practiced polytheism, the expression of which included confirmatory and transformatory rituals. Ritual purification with water occurred in Greek funeral rites, with indication that pollution associated itself suggest that the cleansing had anything to do with establishing proper relationship to the gods, but may have had a purely “practical” force.

A more important spiritual concept to the Greek soldier than that of pollution may have been that of the necessary separation between the warrior’s life and the domestic life. In ancient and classical Greece, city walls held a religious significance as the separation between the sacred and the profane, for inside the walls are the sanctuary and security of domestic peace, while outside the walls warfare and the domestic life from which the warriors of his tale are separated, evoking pathos in the listener; the Iliad’s action describes the soldierly activities and battles of the Greeks and Trojans, while Homer’s metaphors describe the everyday activities which the Greeks have left behind and with living relatives as well as physical location.

Some Classicists believe there is little evidence to suggest that the cleansing had anything to do with establishing proper relationship to the gods, however. Furthermore, a Greek male’s citizenship was based on his membership in his city’s fighting force, his τιμή, honour, was directly related to his performance in the line of duty, and “a purely predatory attitude toward the lives and possessions of one’s enemies was an essential part of archaic and classical Greek warfare. This attitude toward battle makes it unlikely that Greek soldiers would have felt any sense of pollution either from warfare or the soldier’s association with, or proximity to, death or blood; cleansing rites were likely observed for fallen comrades and camps, but may have had a purely “practical” force.

A more important spiritual concept to the Greek soldier than that of pollution may have been that of the necessary separation between the warrior’s life and the domestic life. In ancient and classical Greece, city walls held a religious significance as the separation between the sacred and the profane, for inside the walls are the sanctuary and security of domestic peace, while outside the walls exists the world in which warfare and strife takes place.

In the Iliad, Homer makes extensive use of metaphor to juxtapose the world of warfare and the domestic life from which the warriors of his tale are separated, evoking pathos in the listener; the Iliad’s action describes the soldierly activities and battles of the Greeks and Trojans, while Homer’s metaphors describe the everyday activities which the Greeks have left behind and been separated from for ten years, such as women sewing and farmers reaping.

The soldier may accumulate honour in battle, but he is acutely aware of what he is sacrificing, even if only temporarily, to gain that honour. Homer’s Odyssey and Aeschylus’ Agamemnon are explorations of difficulties the Greek warrior faced as he attempted to return to domestic life after long absence in war. The concept of such separation may have had a sacred significance akin to the idea of the separation of domestic and non-domestic spaces established by walls; it was at least culturally significant to the Greeks of Homer’s and Aeschylus’ times.

Though Greek soldiers may not have had purification rituals to cleanse themselves after battle, Shay proposes that warriors of certain Greek societies, at least, had a form of transformatory, religiously-significant ritual which served to reintegrate them into domestic society after long separation in mandatory military service and, for most, exposure to combat. He writes, “The performances of Athenian tragic theatre - which was a theatre of combat veterans, by combat veterans, and for combat veterans - offered cultural therapy, including purification...The ancient Athenians had a distinctive therapy of purification, healing, and reintegration of returning soldiers that was undertaken as a whole political community. Sacred theatre was one of its primary means of reintegrating the returning veteran into the social sphere as “citizen.”

Shay proposes that soldiers hearing or reciting the Iliad would also have experienced a similar sacred catharsis; thus, this might have been one reason for the works’ significance in Greek culture.

What of the warrior of Imperial Rome? What of homecoming and religion?

Religion was likewise both a public and private affair during Imperial Rome.

Political leaders and military officials were also religious leaders, and the people considered the emperor god-like, if not a god, within one of Rome’s many public cults. Ritual practices were integral to both state and private religion. The Romans accepted that the safety and prosperity of their communities depended upon the gods, whose favour was won and held by correct performance of the full range of cult practices inherited from the past. Bargaining rituals, in which a specific ritual action was performed or promised in return for fulfillment of prayer, as well as confirmatory and transformatory rituals, were common throughout the Roman Empire’s many public and private religious cults.

Within this cultural context, Rome allowed her soldiers to practice in accordance with individual religious beliefs, and the army took part in public religious activities. Among many other state religious rituals, Roman armies underwent ritual purification (known as lustratio exercitus, translating literally as ‘the purification of the army’), sometimes before battle, sometimes after (or sometimes both). This ritual may also have been performed on the Campus Martius (the sacred field dedicated to the Roman god of war, Mars) at the start and end of the military campaign season.

The Roman practice of leading a victorious army under a triumphal arch may also have been a ritual purification; soldiers decorated themselves and their standards for both rituals with laurel, a plant commonly used for purification in other aspects of Roman culture.

Scholars disagree as to the purpose of the purification ritual and the sacred nature of an army’s triumph. Pritchett suggests that Roman generals conducted the lustratio exercitus in order “to remove superstitious dread” from the soldiers before battle. Some scholars argue that the purification ritual was not merely to remove dread before battle, but may have included the use of laurel to “cleanse the army of its bloodshed.” In common with the Greeks, Roman soldiers were unlikely to attach any moral disapprobation to the act of killing itself, or find war immoral. But the performance of the ritual after battle and at the close of the warrior’s season indicate the Romans may have felt that some incidental, religious pollution attached itself to the army or the soldier from nearness to death or blood.

As some point out, Virgil in his imperial epic poem, The Aeneid, supports the idea that the imperial Romans saw some impurity associated with the individual’s presence in combat - Aeneas, having just taken part in battle, states that he must purify himself before approaching his household gods. Others sees the act of battle as a sacred undertaking; therefore, at the end of the campaign season, the soldiers ritually desacralised themselves and also cleansing themselves for their acts of violence in battle.

This idea further suggests a sacred distinction between the warrior and the non-warrior, as the warrior undertook a particular religious duty by fighting which the non-warrior did not. The ceremony performed at a Roman soldier’s retirement, when the emperor, or his proxy, would perform a ritual releasing the soldier from the religious oath he took upon joining the army, transitioning him back into private life, seems to suggest this as well.

These ritual purifications may also have marked the transition for the soldier from chaos back to order. Roman society placed high value on order and Rome’s citizens saw the empire as a civilizing force against the barbaric chaos of other peoples; for them, Roman conquest brought law public order, and structure to uncivilized barbarians as much as it did land and treasure to Rome.

The division between what was civilised (Rome) and was chaotic (barbarians, and thus anyone Rome was at war with) was sacred and sharp, and it was the Roman army which crossed that line to carry order to the peoples of the world. The presence of the ritual after battle and after the campaign season may mark a restorative or transitional moment in which the soldier’s association with chaos in battle against an uncivilized enemy ends and he returns to the orderly world of Roman civilisation.

While no absolute solution can be drawn from the experiences of ancient soldiers, there may be sufficient clues to warrant studying what benefits might be gained from delaying the return of groups of individuals from conflicts in a structured manner, thereby lessening the propensity for PTSD to occur. Particularly, if it were possible to enact rituals of our own - rituals which recognise and free returning soldiers from their traumas and assuage any sense of guilt and culpability - and reinforce that society values them for what they did, we may be better able to deal with PTSD.

Indeed whatever the causes or effects of PTSD suffered by returning service personnel, homecoming is crucial to integrating that person back into his/her family, community, and society. Earlier I talked about research done on British, European and American returning soldiers and the wide discrepancies between the European and the American experience of dealing with PTSD and reintegration.

I think one reason why British soldiers fared better than our American brethren is we had more effective mental health tools and mechanisms in place. I’m sure your brother as he was with the Parachute regiment would have gone through the TRiMS and TLD programme as a way for returning British soldiers to process their tour experience before being allowed back into the fold. It doesn’t work for everyone but certainly catches more in the supportive net who otherwise might have profound difficulties ‘coming home’.

For those who don’t know since 2007 the British armed services have been using the Trauma Risk Management program (TRiM) and the practice of soldiers spending time in a “third location decompression” (TLD) to help the process of homecoming as well as detect early warnings of PTSD. Both have been important tools for British soldiers to process their emotions and experiences.

The good thing about TRiM is that it’s a peer support system designed to assess trauma experienced by soldiers and encourage them to seek help if needed. TLD requires its participants to spend 36 hours in a location away from combat before returning home, often on the bases in Cyprus within the British Sovereign Territory there. Both of these mitigation measures focus on unit or regimental cohesiveness, which is has been well proven to be associated with lower levels of common mental disorders and PTSD. The aim of decompression is to ensure everyone gets a proper mental health briefing and that they are able to speak informally to each other without being judged. In the end it’s an invaluable opportunity to access the social support needed and begin the reintroduction to ‘normal life’.

Of course no system is perfect - look how sprawling the British veteran charities are for instance (Royal British Legion, Poppy Scotland, Combat Stress, Connect Assist, the Ministry of Defence, SSAFA etc) with over 2000 registered veteran charities which leads to confusion about services and support. No measure that is put in place can treat every single soldier but every little bit helps more than it hinders a soldier’s return ‘home’.

In the end to wheel back to your question, the issue of whether the Romans suffered PTSD is probably unanswerable, because the problem itself exposes many of the challenges posed by the historical study of the past.

I do know that the view that the Graeco-Roman world knew PTSD is fast becoming dogma because of popular culture and trendy lefty academic fads in English departments. I find that troubling speaking as both a combat veteran and as a Classicist.

In this debate of nature versus nurture it can hardly be reasonable to conclude that a legionary would have experienced trauma in the same way as a modern day combat veteran – surely his vastly different upbringing, cultural background and combat experience would have resulted in a culturally unique variant of response to that trauma? So to state that the legionary *must* have suffered PTSD seems simplistic and poorly evidenced. Saying a Greek or Roman soldier’s exposure to close combat and the fact that war is hell wherever and whenever it is fought is not enough. Some men would undoubtedly have experienced trauma induced psychological disorder but what that response was, its nature, causes, symptoms, is simply impossible to know, given the current paucity of relevant sources.

Perhaps when we understand PTSD better we’ll have an ability to interpret that thin evidence and put it into a cultural and medical frame of reference - despite wildly different causal factors and conditioning to meet the unique stressors in each of the ancient and modern soldier’s experience of warfare - that will get us close to a definitive answer. Indeed, as we learn more about concussive brain injuries and slowly unravel the various causes of PTSD, I suspect that we may find the evidence will point to a lower frequency of PTSD in the ancient world than that experienced by our troops in the present day. Until then, to be honest, it’s a game of grim conjecture.

If your brother needs more help please DM me and we can discuss ways in which we can help him find the right fit. You already know about the paras own charity for its veterans, Support Our Paras, so nothing I can add there that you don’t already know. My one recommendation would be to reach out to ex-Para and UK SFSG (special forces operator), Dave Radband. Radders is good egg and has used social media to become an outstanding mental health advocate for ex-British veterans.

Once again my apologies for the long answer in two parts but it’s an issue that’s very close to my heart when I think of my own fortunate homecoming from war and I remember those who didn’t come home...and those still fighting the war after they come home.

Thanks for your question.

#question#ask#PTSD#war#rome#greece#antiquity#spartan hoplite#roman legionary#soldier#depression#mental health#warfare#ancient warfare#shell shock#killing#culture#society#classical#mental illness#homecoming#british#british army

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nightmares and Dreams in the Thinking Forest

Kohn’s epilogue to How Forests Think serves to place a kind of structural body upon the already-present text, a rabattement which serves to deepen the process of reading and critiquing exactly what semiotic possibilities are present within the larger structure of Kohn’s proposals, their interaction with one another, the semiotic frameworks he proposes. He presents the book as an anthropological text, and it certainly functions as such, but his work here is not primarily as an anthropologist in the conventional sense, describing the semiotics of certain interactions, the Orientalist conceptualization of a lack of interaction where there “must” be one, or the restructuring and appearance of a disparity, dialectic convention within a kind of eternal human self. Rather, he rejects these in favor of developing through anthropological vocabulary a new potential-anthropology, an anthropology of the beyond-human. The Derridean discourse on the “Animal Other” is not opposed by the continuity that Kohn offers; in fact, if it is evoked, it is evoked as an example of a certain sort of interaction which Kohn would describe as holding a particular differance from the ones that he describes within the space of the Forest, the interactions and assemblages within. Kohn defies a constructivist approach in a strict sense, in that he does not reduce the forest to an entirely human concept, a constructed mark that is incomprehensible to the natural. Rather, the forest exhibits a kind of agnostic relationship to the human, “human” being a certain order of subject-object relations implied by the body of the subject and realized within the larger thinking Forest, the assemblage and anthropological space that the Forest has a hyperreal relationship with, being a kind of simulation of an imagined, ideal forest that is not and moreover never was present.

Presence, and the spiritual content thereof, is a major theme for Kohn in discussing the Forest. For the Runa, a consciousness of the presence of animals that belong to the “spirit masters” that reside deep within the jungle is vital to seeing the animals that are present: whereas Kohn uses his binoculars to number a pack of monkeys as about 30 (calling this a generous estimate) it is described to him as being in the hundreds. The hundreds more are not visible in the sense that is most readily called upon, but rather are present through the signification and multiplicatory properties of representation in the spirit realm. The spirit masters have a certain domain resembling and described as “ownership” over the animals of the forest, which are spiritually far greater, more numerous, than any representation of them within the forest can handle. It is an impossible sort of being, such as the image Kohn lifts from a Jesuit priest’s writings that describes a river with fish so abundant, they in fact constitute the river itself. The river becomes not a flow of water containing fish, or a flow within which there is a second-order flow of fish. Rather, the constituting part of the flow is the fish themselves. This abundance beyond abundance is a fundamental part of the spirit realm. When Kohn discusses the Runa concept of the afterlife, the “always-already” of the domain of the spirit masters, the way in which it is restructured specifically by colonial experience, he begins developing a specific example of a larger Deleuzean principle about capitalist development. Certain spirits wear priestly habits even when local priests have abandoned them, for example. Animals within the Amazon are on the property of the spirit master as if it were a farm, they are the livestock, the chicken and pigs of the spirit masters. An important aspect of this is that, within the ontology of the spirit masters, they are represented not as white men, but men who are as if they are white, as if they have already been and always-already are white, even before it became a comprehensible term.

This example of an indexical reference to whiteness shows how it restructures referential frameworks: Kohn remarks upon how Jesuit missionaries were amused at the apparent-material concept of Heaven as espoused by the Runa as much as they were frustrated at the impossibility of Hell. The former concentrates on the aforementioned discussion of the spirits, their realm, the ascendence into a relationship with the spirit masters: in a Catholic interpretation, this is a fully-developed understanding of the notion that all are Saints in the proper sense, rewarded in Heaven in a specific and tangible fashion. The milk and honey that the Jesuits may have spoken of would be rather literal, just as the image of white authority depending on Jesus for its implementation relies again on this indexical whiteness. Conversely, for the Runa there is no hell, with death there is not a danger of losing the spirit except if the spirit is allowed to wander, is not properly sent off through certain rituals. There can be hell, they admit but not for the Runa. Rather, if there is a recognition of hell, it is populated by others, specifically the white and black races that the Runa have come in contact with as a result of colonialism. First, one finds the striking antiblackness of such a statement, in that it implies a metapysics based at least partially in race, with an eternal and marked subjugation of a black race, black bodies, continuing even after death.

However, the body is not the totality of that which it suggests, is not simply confined to its colonial appearance. Kohn references a story where a visiting Spaniard is greeted kindly for his gifts of golden religious items, but when he jokes that he would marry one of the women, they call him a devil. In one account how the Runa gained their identity, it is not through a process of civilization and colonization that the Runa became more like the white colonizers, with clothes and salt symbolizing civilized life. Rather, a flood separated the Runa from part of their population, washed away and eventually descending into a savage state. In this move toward disorder, a spiritual degradation brought about by an absence of this civilizing salt, the notion of an immutability to Runa identity makes itself known. It is through what Kohn describes as the “tools of whiteness” that certain orders of control are signified, and while these are not free from the colonial as some might wish to claim in defense of “civilization,” it would be naïve to insist that there is not a genuine process of engagement with these tools on the part of the Runa. Kohn’s own backpack is such an item, just as his beard is, other objects part of the shamanistic series of syncretic signifiers that make up daily practice, daily life for the Runa. Kohn’s backpack is a signifier of him as some other sort of person, one that is certainly not of the Runa in a conventional sense but by no means alien to them. His location as a Shaman, as holding a shamanistic relationship to others, is at once an indication of him as an outsider and an acceptance, a process of welcoming and recognizing him in kind.

By Kohn’s account, the mixture of pre-colonial, colonized, and post-colonial (and arguably neo-colonial) signifiers results in a kind of Oedipal structure of signification: to reference Deleuze and Guattari describing capitalism as a “nightmare” that lurks in the shadows outside the fire of early man right through into a future-of-futures, the opening of not only the “future” but all possible futures in a fashion that embodies not merely the eternal but the infinite, infinity contained within capitalist totality, one finds that there is a certain sort of totality comprised by the metaphysical, ontological, and epistemic traditions of the Runa within the forest as its own totality. Of course, this is not to say that the Runa are outside of capitalism, as this would lead to a wrongheaded evocation of primitivism that is useless not because of an inherent property of primitivist thought but rather because it constitutes a misapplication. Certain structures of “civilization” are core to this subjectivity, and even in retaining a greater rhizomal structure in opposition to colonial arborescence, this is within a forest that has become deeply embedded within colonial and capitalist violence, striated by the rhizomal creep of capitalist machines like seen during the rubber boom that Kohn evokes. The structure of this is such that the “present” structure of experience, the “current” is structured by a continual process of reterritorialization, an understanding such that the Runa have an identity that does not originate in ascent, but rather as unmarked by the descent of others. In this fashion, one finds the means by which “history” and its domain are rendered external, are unable to be marked upon a dasein that is relayed within the Runa vocabulary, the way that death itself is not imagined as part of the self but rather in relation to the living and the spirit.

Kohn describes how the huaturitu supai, the priestly demon mentioned previously, is not to be gazed upon specifically because of how it creates a kind of Sartrean relationship of objectification: one looks, and by looking one is asserting one’s self, one’s “I”-ness, one’s subjectivity in a phenomenological sense, but by gazing upon the huaturitu supai one is then transfigured into “you” from “I” such that one is being addressed, is able to be understood as an object, is taken forever from the living and moreover the possibility of living. It is in subjectivity, in the interrelation of subjects, that Kohn’s forest thinks, that it begins to make itself known. Kohn discusses the subjectivity of the jaguar, almost in an echo of the Derridean cat, as requiring one’s gaze, one’s recognition, in order for the jaguar to regard oneself as a subject. Derrida’s cat is shameless yet naked, a reminder of one’s own nakedness that reflects one’s own subjectivity back. Meanwhile, it is the jaguar who must recognize subjectivity in the sleeping human, find the possible-gaze in a fellow predator in the closed eyes of a sleeping human, such that the human will be recognized as predator rather than prey, as able to be attacked. The “I” of the eye, the jaguar’s recognition, is a literal recourse from becoming an object in relation to the jaguar as a subject, the recognition of jaguar subjectivity both in communicating toward such a subjectivity, and in recognizing that such a subjectivity will perceive this and respond in kind. The dual structuring at hand, then involves the recognition of certain sorts of objects, subjects, and relating one to another in a fashion that leads to a certain structure that is arborescent in a certain sense, but is overwhelmingly able to resignify and restructure itself if one is careless. The relations at hand are multifarious, can be deconstructed and reversed with certain acts, the taking-on of certain forms, the means by which the spirits of the Forest interact with the human-as-such. When hunting game, a successful kill must be recognized and met with the repayment of the spirit masters. Conversely, making an offering is an attempt to draw out the same relationship, and Kohn describes how an unsuccessful attempt at this is described as “stingy” with the same tone directed at a politician who visited Ávila without any cigarettes or alcohol to give. These relationships take on the “forms” that Kohn describes as certain signifiers, certain carriers and arbiters of semiotic relationships, certain processes of meaning-making.

The structure of “form” in rising up into human construction is, I would argue, not an indication that there is something more basic than human apprehension and construction but rather the transfiguration of the landscape through a radical act of ecological restructuring, one that Kohn rightfully describes as emanating from outside the human but in part determined and overcoded by human forms, a certain conceptual formalism that he uses to describe the ways in which the naming and realization of forms takes place. He gives the example of the stick bug, and refers to it continually: it is named as such because it resembles a stick, an easy enough concept to understand. However, the stick bug was not born resembling a stick, was not created as a mimicry of a stick. Rather, the form-of-a-stick was imparted upon it gradually, through a flow of evolutionary moments, events, where the form-of-a-stick was mimicked by the bodies of its ancestors, and more stick-like ancestors tended to propagate. Some that looked less like sticks inevitably outlived and bred in spite of this, just as some that may have been incredible mimicries of sticks were eaten. The form is part of what Kohn describes as a process of Emergence in the Forest, where the form becomes clear.

Kohn’s “forms” can be incorporated into an analysis of what ecosystems fundamentally stand for, in describing emergent properties, the means by which one finds emergence as linked to processes of development and indeed, colonial hierarchy: the rubber boom structured the relations between colonizer and colonized, as well as intracolonial subjectivities, a kind of knot where an arboreal hierarchically emanated out from the mouth of the Amazon into the smaller and smaller tributaries of the river, each branch and each smaller and smaller division a reflection of the original, a kind of dissolution of hierarchy where form emerges as a higher order, independent from the order it is built upon, contained within, and yet unable to exist without the flow constituted by lower-level structures. As such, there is a continual process whereby the emergence of higher-order structures relies specifically upon lower-order ones that reflect, recognize, restructure themselves around those other flows in acts of resemblance. There is a blurring between exactly how one would apply the models of rizomality and arborescence in strict terms (a heartening thing, given that the strictness often imparted to application of Deleuzean notions of structure implies the very ontology that calcifies and stagnates the flows of schizoanalytic theory) but rather sees the continually resembling, tangled, mess-of-messes, collection of collections that the Runa describe a particular plant as, the disorder within mirroring the apparent disorder of the entire organism. The structure by which, then, this relates to ecological study, the understanding and demarcation of the ecosystem as a sort of form, as a collection of forms and interrelated objects, subjects, subjectivities requires an application of the Virtual as a demarcation of space.

Kohn describes the means by which “Amu” constitutes a notion that is not quite spirit, soul, or other terms applied to it in a kind of colonial determination, but rather a word that is far more like Dasein in its apparent-untranslatability: it is not unable to be translated, as such a notion requires a prescriptivist concept of direct linguistic correspondence, but rather that it holds a certain weight, a means of locating the self in regard to forms and their recognition, the emergence and recognition of forms within the relations of subjects and objects, subjects to one another through objects, the complexities of subjectivities related to one another without a direct contact, at a distance, through the kinds of contact that are created through processes of ecological change, revival, collapse. Kohn describes a “virtual realm of the masters” that is marked through a kind of digital location inside the forest, but reflected in emergence, in the understanding of forest as ecological hyperobject, as not just a present series of objects but in fact an emerging expanse that creates not only future, but the “in futuro” that is vital to the relationship between spirits and humans. It is in specific emergence, dictation of the possibilities of future and possible-possibilities, the expanding presence of potentiality in an ecosystem and the way in which the ecosystem reflects and restructures potential that emergence is understood. This is reflected, of course, in the rhetoric of necessity regarding discourses on ecological collapse. Radical changes to the very concept of ecosystem are needed in order to survive, but a strictly primitivist argument is one that largely misunderstands the means by which emergence in ecosystems presents not merely human as uniquely-human, but the interrelation of subjectivities through inter-species pidgins, the ordering of humans as not merely of a higher order than animals, but in fact of a lower order in relation to the spirit that is relayed through the animal to the higher-order human, the affirmation of the spirit-as-such far more “Real” than many metaphysics would allow. The “Real” then is in fact part of a hyperreal, a kind of simulacra of the ecosystem where understanding of it, the emergence of the ecosystem, is dictated by a relation of subject to object and moreover subjects within greater shared subjectivities such that it is through the emergence of these forms that the notion of civilization, colonization, collapse, and other changes in structure become comprehensible.

The complexity of the ecological as a sort-of-system, a larger structure signified by naming and confining it to singular ecological instances rather than a decentralized, rhizomal weight that is continually pulling down, that is realizing new emergent forms of collapse, producing-production from the greater structure of consumption-production as a first world luxury and third world necessity, the shifting means by which the two are understood as respectively salvageable and untenable, the neocolonialism of capitalist environmentalist ideology, all of this is part of an emerging structure wherein the forms of ecological collapse are dramatic, but cannot be understood without reference to their realization as part of a larger emergence. It is in certain relations that the emergence of the Forest is possible, just as it is in emergence that a larger ecosystem, a larger global body, can be understood. This body is marked, marked-as-one, understood specifically because of how it is able to be structured by subjectivity. Understanding how Forests think, how the relationships of individual experience create emergence far beyond the individual, understanding causality in a sense that opens up the domain of the spirit, of ritual and invocation, of shamanist thinking, the Virtual of the Spirits, is vital if one wishes to assert capitalist expanse, neoliberal ideology, the schizophrenic consumption of late capitalism.

2 notes

·

View notes