#ancient warfare

Text

A hoplite stands in attacking position over a (now lost) fallen foe. Ancient Greek marble relief (possibly part of an Athenian state memorial), ca. 330 BCE; artist unknown. Now in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen. Photo credit: ChrisO/Wikimedia Commons.

#classics#tagamemnon#Ancient Greece#Hellenistic period#ancient warfare#hoplite#art#art history#ancient art#Greek art#Ancient Greek art#Hellenistic art#sculpture#relief sculpture#portrait sculpture#marble#stonework#carving#Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

496 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Warriors of History --- Syracusan Hoplite

from Ancient History Guy

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spartans and their Aversion to Ranged Warfare

Just having thoughts about that whole common knowledge take that "the Spartans were eventually defeated because they couldn't adapt away from phalanx warfare" and how wrong that really is, based on the evidence we have.

This concept really comes down to two assumptions: First, that they were ideologically opposed to, and didn't use, ranged weapons (bows and arrows in particular); and second, that they were entirely married to infantry warfare to the exclusion of cavalry.

I've covered the cavalry question in my other post The Horses of Lakedaimon, but to summarise very briefly, there is explicit reference to mounted troops travelling with the Spartan army in the primary sources, but good reason to suppose they weren't Spartiates in the technical sense.

To reiterate, when ancient writers talked about Spartans, they did so in the technical sense of Spartiates - full Spartan citizens, the homoioi. If we look at the writing of Thucydides, for example, it's reasonable to suppose that he was getting his information on army numbers from the Spartans themselves (possibly deserters), and they certainly wouldn't have counted the non-homoioi.

As I keep banging on about, the three hundred at Thermopylai was what Spartans saw in a force of over three thousand men. We really can't trust the numbers.

We know that at least by the fifth century and the period I study, perioikoi and freed helots had become a fixed element in the Spartan army. None of these groups were citizens and wouldn't be counted as Spartans, but they were definitely there.

Less certainly, but worth considering, is the group of men who were born to Spartan parents but for one reason or another never made it to full citizenship or had lost it - the Hypomeiones. They were almost certainly eligible for some involvement with the army/state service - though how much, and whether on foreign service, we can't say. And consider - this group were only non-Spartan in the most technical of senses and they still weren't counted anywhere.

So, while full Spartan citizens probably were exclusively infantrymen, the Spartan army as a whole certainly wasn't.

The other thing that needs to be pointed out is that Sparta always had allies with them who provided these specialist skills that the homoioi took no part in. Boeotia, for example, regularly supplied them with large cavalry forces; others supplied peltasts and archers. The Spartans were always in charge of these mixed forces - so to say that Spartans didn't engage with these forms of warfare, and use them effectively, is to take a rather one-eyed, narrow view of what constituted a Spartan army.

Again, a true Spartiate probably wasn't a peltast or archer, but a Spartan army definitely contained these elements.

As far as I can recall, and I'm really just thinking out loud here, the basis for believing that they were opposed to ranged warfare comes from Thucydides and the aftermath of the Battle of Sphakteria.

He reports a Spartan's response to being heckled by an Athenian, something to the effect that the dead must've been their bravest (because they didn't surrender); and the Spartan retorted that the 'spindle' (ie. arrow, made effeminate) would be a great weapon if it could pick out the brave. [Thuc. 4.40 - had to look that up :)]

So yeah. As always, the truth is so many shades of grey.

I can't say I've spent a lot of time reading about the decline of Spartan power in the fourth century (in truth, I find it kinda depressing), but my opinion is that their eventual defeat was caused by a complex mix of factors - population 'decline' (aka, poverty), abandonment by allies, and complacency, amongst others - and as always, pinning it to just one failing (if it can be called that) is bound to be wrong.

#sparta#ancient sparta#ancient greece#lakedaimon#ancient history#greek history#spartan history#spartan army#ancient warfare

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Of course. Why am I not surprised.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

How did Ancient Egypt become a military power to be reckoned with? It’s all down to their innovative approach to deadly weaponry.

#ancient Egypt#weapons#Hittites#Kapesh#Khopesh#Sword#composite bow#chariot#ancient warfare#ancient#history#ancient origins

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

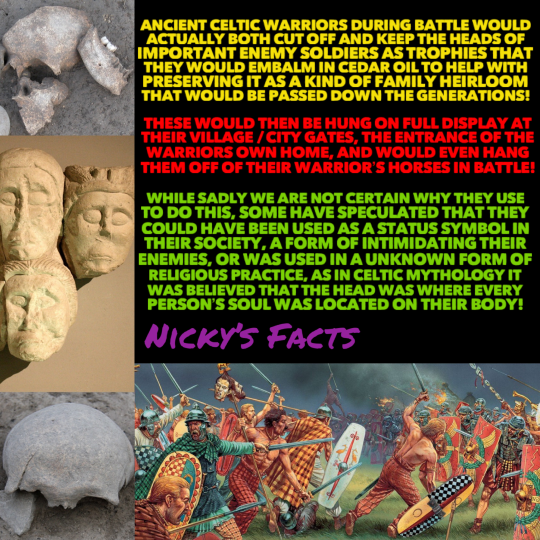

Guess you could never say, the ancient Celtic people ever went over their heads!

💀😂💀

#history#ancient celts#heads#family heirloom#skulls#ancient#celtic history#gaul#ancient romans#france#ancient practices#european history#celtic#ancient culture#celtic mythology#ancient history#spooky facts#classical age#french history#ancient warfare#cedar oil#history mystery#nickys facts

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

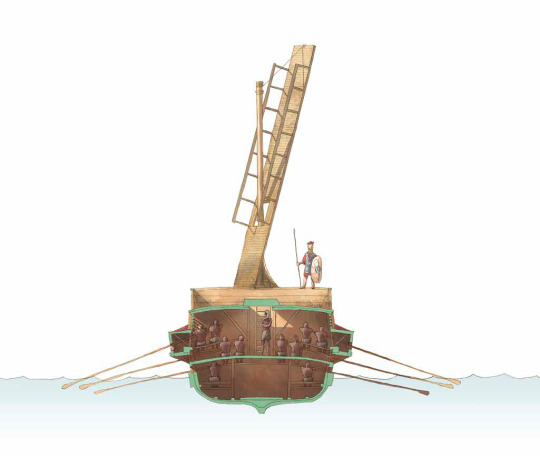

Crosscut of the quinquereme, the warship that was ubiquitous in ancient navies. It had a set of three oars on each side, handled by five rowers, hence the name.

Contrary to the popular image of slaves rowing these ships, the majority of the rowers were free albeit poor citizens as it required skill and experience.

This particular quinquereme is equipped with the so-called "Corvus", a boarding device invented and employed by Romans to great effect in the First Punic War.

(Image Source: Ancient Warfare Magazine)

#ancient rome#ancient world#ancient civilizations#ancient culture#ancient greece#punic wars#corvus#warship#ancient warfare#the roman republic#military technology#ancient military#ancient warship

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Old-school matchlock gun reproduction of the Ming dynasty item from Qingfan (慶藩). The original dates from the Wanli period. It is the first Ming matchlock gun in true sense.

Prototypes are on display at the Xuzhou Museum (徐州博物館).

Photo: ©寒光甲冑工作室

#chinese martial arts#chinese warfare#ming dynasty#ancient china#chinese history#Wanli period#wanli#matchlock#ancient weapons#ancient warfare#medieval#martial arts#chinese military#military#ancient warrior#historical

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Due to my capstone project need community involvement, I would like yall to help me plz,

My project is on the Peloponnese war and I would like to know yall own opinion on the war and what u think cause it. I promise to give yall credit for it and make a slide with yall name in it

#assassin's creed#assassin's creed odyssey#ancient#greece#history#ancient greek literature#ancient greece#ancient warfare#ancient world#ancient sparta#alexios#kassandra#athens#greek tumblr

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

S. Fachard-E.M. Harris (editors) The Destruction of Cities in the Ancient Greek World. Integrating the Archaeological and Literary Evidence, Cambridge University Press 2021

Table of Contents

1. Introduction: destruction, survival, and recovery in the ancient Greek world Sylvian Fachard and Edward M. Harris

2. Destruction, abandon, reoccupation: What Microstratigraphy and Micromorphology tell us Panagiotis Karkanas

3. Miletus after the disaster of 494 B.C.: Refoundation or recovery? Hans Lohmann

4. The Persian destruction of Athens: Sources and Archaeology John Mckesson Camp

5. The Carthaginian conquest and destruction of Selinus in 409 B.C.: Diodorus and archaeology Clemente Marconi

6. Ancient Methone (354 B.C.): Destruction and abandonment Manthos Bessios, Athina Athanassiadou, and Konstantinos Noulas

7. The destruction of cities in Northern Greece during the Classical and Hellenistic periods: The numismatic evidence Christos Gatzolis and Selene Psoma

8. Eretria's “destructions” during the Hellenistic period and their impact on the city's development Guy Ackermann (translated by E. M. Harris and S. Fachard)

9. Rhodes ca. 227 B.C.: Destruction and recovery Alain Bresson

10. Destruction, survival and colonisation: Effects of the Roman arrival to Epirus Björn Forsén

11. From the destruction of Corinth to Colonia Laus Iulia Corinthiensis Charles K. Williams, Nancy Bookidis, Kathleen W. Slane, and with Stephen Tracy

12. Sulla and the siege of Athens: Reconsidering crisis, survival, and recovery in the 1st B.C. Dylan K. Rogers

13. The Herulian invasion in Athens (A.D 267): The archaeological evidence Lamprini Chioti

14. Epilogue. The survival of cities after military devastation: Comparing the classical Greek and Roman experience John Bintliff

15. Appendix. The destruction and survival of cities.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Greek(Medieval) Warfare;

Everyone is debating on whether the Greeks fought in a phalanx of bronze;

No one is wondering if the Greeks could afford to fight in a phalanx of bronze.

#medieval warfare#ancient warfare#ancient warrior#ancient greeks#phalanx#military technology#military history#historical#medieval#middle ages#ancient greece#greece#alexander the great#greek history#ancient greek#ancient history

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Greek bronze infantryman's helmet (Apulo-Corinthian style, type A). Manufactured in Apulia, Magna Graecia (present-day Puglia, Italy), ca. 510 BCE; now in the British Museum.

#classics#tagamemnon#Ancient Greece#ancient history#ancient warfare#Archaic Greece#Magna Graecia#art#art history#ancient art#Greek art#Ancient Greek art#Archaic Greek art#South Italian art#Apulia#Apulian art#helmet#bronze#metalwork#bronzework#British Museum

360 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Halia signaled for the Vulchervi to convene. Slowly, they stirred from their sour-smelling swarm, spreading to encircle the empress. Under a mantle of humid feathers, sinister whispers swirled."

-Padhopper by Chervis Mingus

For free Padhopper pages, visit frogiverse.com

#fantasy#frogs#nature#archaeology#worldbuilding#padhopper#empires#history#vultures#frogiverse#world building#my writing#ancient artifacts#eagles#birds of prey#birds of war#empress#queen#ancient warfare#ancient civilizations#ancient history#feathers#free book#quotes#original

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

You know when you’re talking to someone and they reveal they read Ancient Warfare Magazine. And suddenly everything about them clicks into place

#dear lord I cannot cope with military history#50% of classicists be like#classics memes#ancient warfare#tagamemnon#classical studies#ancient history memes#ancient greek#ancient history

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not me rewatching Suits for the millionth time, and now I’m itching to write Harvey Spectre/Donna Paulsen fanfiction. He’s just so pretty in his suit! And their banter is sublime! But I’m researching ancient battles for my Game of Thrones fic, and it has to take precedence or I’ll lose the last braincell I have. I just wanted to write romance with lots of dragon flying 🤭 and now I’m here. Planning a damn war. It’s actually interesting, tbh. I can’t wait to kill some fictional people. I’m just feeling sorry for myself. Everything hurts, but I haven’t been stabbed or shot by an arrow, so it’s fine.

#suits#suits tv#harvey specter#i am so sorry#no one asked#fanfiction#yes please#he is so beautiful#i want to write#suits usa#fanfic#gabriel macht#game of thrones#fanfic writer#game of thrones fanfiction#ancient warfare#i have so many questions#stabby#why do i do this to myself#battle#who thought this was a good idea#oh yeah#i did this to myself#dragons#i only have myself to blame#writers things#writer life#writing is suffering#sometimes#fibro flare

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Many strategic practitioners, such as Thucydides, Xenophon, and Alexander chronicled their military experiences and thoughts on war. Battles across centuries of Ancient Greek warfare provide modern scholars and practitioners with a multitude of case studies that offer insights into military strategy and international relations which are still relevant today.

The Athenian general and historian Thucydides, who himself fought in the war, is the most famous source of information on the War between Sparta and Athens. His seminal work on the Peloponnesian War has massively influenced how contemporary military practitioners and academics think about the nature of war.

Xenophon was a military practitioner and writer. In 401 BC, Xenophon accompanied ten thousand Greek mercenaries on an expedition to Asia Minor. Their objective was to help Cyrus the Younger overthrow his brother, Artaxerxes, and seize the Persian throne.

Alexander the Great is perhaps history’s most famous military figure. Before his death at the age of thirty-two, Alexander had conquered a vast territory across Europe and Asia.

#history#ancient greek#ancient warfare#alexander the great#peloponnesian war#historical military general#ancient

3 notes

·

View notes