#Hegira

Photo

Hegira by Alan Gutierrez

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fatimah bint Muhammad - World History Encyclopedia

https://www.worldhistory.org/Fatimah_bint_Muhammad/

View On WordPress

#619#632#Abu Bakr#Abu Talib#Ahl al-Bayt#al-Siddiqah#al-Tahirah#al-Zahta#Ali ibn abi-Talib#Arabia#Arabian Peninsula#Ashura Festival#Caliph#Fatima bint Muhammad#Hassan#Hegira#Hijab#Hussayn#Imams#Islam#Jannat al-Baqi#Khadijah#Lady of Islam#Mecca#Medina#Mother of Imams#Muawiya#Muhammad#Muharram#Prophet

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Word of the Day – Hegira

Word of the Day – Hegira

Noun: Hegira

a journey especially when undertaken to escape from a dangerous or undesirable situation

Synonyms:

abandonment

adieu

bow out

congé

decampment

desertion

egress

egression.

Usage:

“Nevertheless, though it might mean that they must again pursue their weary hegira, the dominant race did not appear to have crowded the available living space.”

Encountered:

While reading Robert A.…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

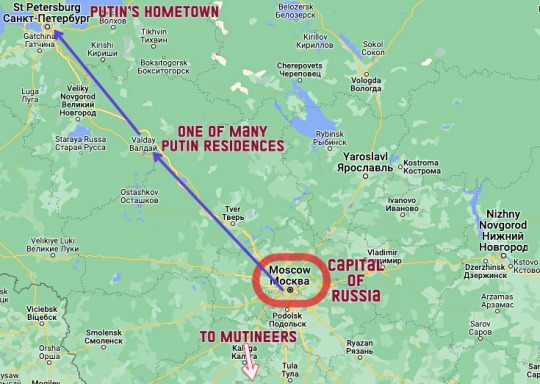

Where Vladimir Putin spent his coup.

The Russian government’s Il-96−300PU aircraft took off from Vnukovo Airport at 14:16 local time and headed for Valdai, one of Putin’s residences, it said.

However, Hajun said it was not known who was on board the plane, although it was an aircraft which has been used by the Russian dictator several times.

The plane reportedly disappeared from radars near the Russian city of Tver (about 150 kilometers from Valdai), the independent Russian website Important Stories (IStories) said on Telegram on June 24. The media outlet claims that the plane is “equipped to control the armed forces.”

While commenting on Putin’s whereabouts to the state-controlled TASS news agency, his press secretary Dmitry Peskov said his boss “is working in the Kremlin.”

Something we should never believe is information from an official Kremlin spokesperson. 🤡

The Insider, a Russian investigative journalism project, also writes that as of 3 p.m. local time, another Russian special forces aircraft had landed in St. Petersburg.

The independent news outlet Mozhem Obyasnit, in turn, reports that Russian officials are fleeing from Moscow on business jets – at least three flights served by the Special Flight Unit“Rossiya” of the Russian President’s Administration have already departed for St. Petersburg.

Sometimes Valdai is transliterated as Valday. Google Maps prefers the latter. In any case, it is 353 km/220 miles by air from Moscow.

#russia#mutiny#attempted coup#vladimir putin#yevgeny prigozhin#wagner group#valday#st. petersburg#putin's hegira#invasion of ukraine#россия#владимир путин#мятеж#чвк вагнер#евгений пригожин#путин хуйло#путин – это лжедмитрий iv а не пётр великий#валдай#санкт-петербург#москва#путин бежит#геть з україни#україна переможе#слава україні!#героям слава!

2 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Such - Hegira

youtube

0 notes

Text

hilda band au where the squad start a rock band called “The Freaky Four” where hilda is the drummer, frida is the guitarist, louise is the rhythm guitarist (sings the harmonies) david is the main singer and they usually preform for the sparrow scouts at the auditorium in the scout hall, but eventually get their own stage

(i dont know how bands work but ill try to figure it out LMAO)

some songs that i imagine them to play: king for a day by pierce the veil, partner in crime by madilyn mei (I LOVE THE SONG OKAY), hegira emigre by of montreal etc etc the edgy songs

id make more headcannons but im sleeby

#hilda the series#hilda#hilda netflix#hilda (hilda)#hilda the show#hilda spoilers#frida hilda#hilda frida#hilda david#david hilda#hilda louise#louise hilda#hilda au#band au

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

I remember seeing a post that showed Camille and Marat responding to each other through their newspapers. I don’t know much about Marat’s feelings towards Camille or vise versa and was wondering if you knew anything about their relationship. Thank you!

The first connection I’ve been able to find between Marat and Desmoulins is from December 28 1789, where we find the following letter from the former to the latter.

All citizens who have a soul, monsieur, are friends of mine, and you are at the head of those who have proven themselves. I accept with satisfaction your proposition, and beg you to accept the assurance of all my esteem and my sincere attachment.

According to La correspondance de Marat (1908) where it is cited, this is likely the first letter Marat ever wrote to Camille. As can be seen from it, Marat is responding to a proposition Camille has made. Exactly what it was about is left unanswered, but seeing as Camille had started his journal Révolutions de France et de Brabant just a month earlier (the first number was released on November 28), perhaps it regarded an agreement on the political orientation the two journalists had decided to take.

The first of the around 190 times Camille mentions Marat in Révolutions de France et de Brabant is in its eight number (January 16 1790). We do however have to wait until the following number, when Camille includes a part titled ”Affaire Marat,” to find something more meaningful when to comes to the relationship between the two:

I said one day to M. Marat, in the only interview I have had with him, what I thought of the excessive haste in judging, of his still greater facility in accusing, the danger of some of his opinions, from the lack of restraint in anger, his face being always the same, and as inflamed against M. Bailly as against J. F. Maury. I did not hide from him that the rumor was being spread that he was the instrument of aristocrats who employed him to sow trouble, and to rouse the people against any species of administration: but he replied in a way that made me close my mouth, with this piece which ends his denounciation of M. Necker: “The enemies of the people, who are mine, say that my pen is sold. And to whom, by grace, would I be sold? Is it in the National Assembly, against which I have risen so many times, of which I have attacked several disastrous decrees, and which I have so often called back to its duties? Is it to the crown, whose odious usurpations, whose formidable prerogatives I have always attacked? [Camille then publishes a long monologue where Marat assures that he isn’t working for anyone but the people, following the direction of no one but his heart]. There you have (Camille writes), I will not only say one of the most beautiful pieces of eloquence that I have ever seen; but also one of courage, soul and great character. Speaking of the freedom of the press, in the next number I will reflect a bit on the capture of M. Marat.

In number 15 (March 8 1790), Camille publishes a letter to him from Linguet, where the latter asks him if he knows where Marat is. Camille responds by the following footnote, adressed to Marat:

And you, M. Marat, respond to Mr. Linguet's postscript. Where are you? Adam ubi es? When God called Adam thus, he mocked our first father; for God, who sees all, was unable to not know where Adam was. For me, I don't know where the friend of the people is. Not a day goes by without me being asked for news about him. Could he be in the lion's den? say the patriots. I answer, M. Marat, that since your second hegira, I have received from you a dissertation on the freedom of the press; that I did not have enough space to infer it in my journal; that since then I have had no news from you. I answer like Madeleine: Nescio alii posuerunt eum. Please show yourself, M. Marat; reassure the good citizens. One has forgotten your great services to see only your very forgivable faults. Miserable condition of a journalist! Those whom he amused, whom he interested, soon forget him; those whom he has wounded are irreconcilable. He must take as his motto that which Cicero gives to a lieutenant-criminal: Cui dolet meminit, cui placet oblivifcitur.

La correspondance de Marat mentions a one page long letter from Marat to Camille dated May 1790, that they unfortunately only know about through an autograph catalogue. The catalogue entry went as follows: ”Letter signed, with the subscription and three autograph words, to Camille Desmoulins; Paris, May 1790, 1 p. in-49”

On June 24 1790 we find a letter from Marat to Camille where he suggests publishing a series of articles jointly in l’Ami du peuple and Révolutions de France et de Brabant — ”Believe, dear brother in arms, that nothing matters more to the triumph of liberty, to the happiness of the nation, than to enlighten the citizens on their rights and to form the public mind. This is what I urge you to work tirelessly on, by recording in our sheets a series of selected excerpts on the constitution; a real way to appreciate the work of our representatives at their true value.” Desmoulins did however never publish the article Marat attached to the letter, choosing instead to reprint one of his earlier ones.

From an unspecified date the same month we also have yet another letter from Marat to Camille.

Dear brother in arms,

I ask you for a place in your next number for the included piece, too voluminous for my paper, and too interesting not to see the light of day at the present moment, when the conscript fathers move heaven and earth to prevent the people from revising their work, from rejecting all their decrees prejudicial to their rights, and granting their sanction only to those who are just and wise

A month later, in number 70 of l’Ami du Peuple (July 23 1790) Marat, while in hiding, includes a letter from him to Camille in an attempt to comfort him after death threats were pronounced against both of them during the Feast of the Federation:

I like to believe that my brother in arms, Camille Desmoulins, won’t abandon the fatherland and renounce the care of his glory by losing courage in the middle of his noble career. He is revolted to have heard deputies of the federation ask for his head. But a few drunk or abused men don't make up the public, and that public itself, should it be lead astray, still contains a large number of estimable citizens, full of admiration and gratitude for their generous supporters. Finally, even if the people was to be composed only of vile and ungrateful men, would the true philosopher close his heart to the love of humanity as soon as he sees no more reward worldly passions as the price for his virtue? O my friend, what fate brighter for a weak mortal than power, here-down, rise to the rank of the gods! Feel all the dignity of your being, and be convinced that among your persecutors there are a thousand who are humiliated by their nullity, their vileness, there are a thousand who envy your destinies. Few men, I know it, would be in the mood to grind for the salvation of the fatherland. But what! why would a citizen who has no parents, no wife, no children to support, fear therefore to run some dangers to save a large nation? while thousands of men abandon the care of their affairs, tear themselves away from the bosom of their families, defy perils, fatigue, hunger, and expose themselves to a thousand deaths to fly at the voice of a disdainful and superb master, bring desolation to distant lands, cut the throats of the unfortunates whom they have never seen and barely heard of! What ! many legions will not fear to cover themselves with crimes for eight sols a day, and the love of humanity, the love of glory will be too weak, to lead the wise to defy the slightest danger! I do not try to give myself incense; but my friend, your fate is still far from as harsh as mine! For eighteen months, condemned to all kinds of deprivations, excess of work and vigils, tigues, exposed to a thousand dangers, surrounded by spies and assassins and forced to keep myself together for the fatherland, I run from retreat to retreat, often without being able to sleep two nights in the same bed, and yet I have never been happier in my life; the greatness of the cause that I defend elevates my courage above fear; the feeling of the good that I try to do, of the evils that I seek to prevent, comforts me in my misfortune, and the hope of a brilliant triumph penetrates my soul with a sweet voluptuousness. Considering you like to laugh, here are some anecdotes to cheer you up, by giving you an idea of the agitation of my life since the start of the revolution. [he then goes on to tell a long anecdote about how he escaped arrest a few days earlier] Dear Desmoulins, you who know so well how to amuse your reader, come learn to laugh with me; but keep on energetically fighting the enemies of the revolution and receive the omen of victory.

A few days later, Marat and Desmoulins get into an argument about the former’s newly released pampleth C’en est fait de nous (the origin of his (in)famous words ”five or six hundred heads chopped off would assure you peace, liberty and happiness.”) Camille reacted both on the violence, as well as the pampleth denouncing of the deputy Jean Philippe Garran de Coulon, and in number 37 of Révolutions de France et de Brabant (August 9 1790) he recounts the conversation he and Marat had about it, which according to him took place on July 29.

I was so indignant that I immediately ran to see Marat to exclaim that he was spoiling the good cause, that he was ruining us with his intemperate patriotism, that since he had just denounced the most good man I had met in my life, our Cato, M. Garran, I would no longer call him the divine Marat. […] “M. Marat,” I said to him, shaking my head, “my dear Marat, you will do yourself bad business, and you will be obliged to put a sea between the Châtelet and yourself a second time. Five or six hundred heads chopped off! Admit to me that that is too far. You are the dramaturge of the journalists. The Danaides, the Barmecides are nothing in comparison to your tragedies. You cut the throats of all the characters in the play, right down to the blower. You are therefore unaware that the outraged tragedy becomes cold. You are going to tell me that five or six hundred heads chopped off are nothing, when it is a question of saving 26 million men, that Durosoy, in his Gazette de Paris, shouts every day to the former nobles: ”band together, take helmets, thighs, the rusty swords of your fathers, cut the throat of the entire nation!,” that you can only be considered as the patriotic version of Durosoy, and that the Gazette de Paris is still well more soaked in blood than l’Ami du peuple is. M. Marat, do you also want to fight the one you call Sylla, only like Marius? Five to six hundred heads chopped off!.. it really is a proscription. I know well that your tables of proscription will not remove the hair from the head of a single aristocrat; At least you should make a roll call of these five or six hundred rascals, so as not to spread consternation in all the families. As for me, you know that it’s been a long time since I resigned as Attorney General of the Lantern; I think that this great charge, like dictatorship, should only last a day, and sometimes only an hour. Pardon, dear Marat, if my green youth gives advice to a head as healthy as yours, which is more matured than mine by years and experience; but you really compromise your friends, and you will force them to break with you. Do you see, I added, that I am more circumspect than you? Since I learned that they wanted my demise, have you noticed how I avoid them getting hold of me. They were waiting for me at the feast of the federation; and according to the facts and my principles, the step was slippery. But I saw Malouet, the key to the pack, arrive. Instead of allowing myself to be thrown back into the Champ-de-Mars, I tracked him down by speaking of the triumph of Paul Emile, and by leading him from the triumphal gate to the Esquiline gate and to the Cœlimontane gate. I just translated Plutarch word for word. Come the blacks when they want. I defy them to assign me to the Châtelet, or else they will have to have Plutarch, Amyot and Madame Dacier also assigned. When despotism reigns, all that remains for the friends of liberty is to relieve their court by depicting happier times. Volaire writes the death of Caesar; Corneille that of Pompey; and Fenelon does his Telemachus; for despotism itself has never gone so far as to defend with the brush of the historian, or of the poet, the picture of anterior times.” Mr. Marat allowed me to rant on, and then refuted me with a single word: ”I DISAGREE.” (JE DÉSAVOUE)

Marat responded to this through a letter inserted in number 193 of his journal (August 16 1790):

Despite all your wit, my dear Camille, you are still very new in politics. Perhaps this amiable gaiety which forms the basis of your character, and which pierces your pen in the most serious subjects, is opposed to the seriousness of the reflection, and to the solidity of the discussions which are the result. I say it with regret, devoting your pen to the fatherland, how much better you would serve it, if your progress was firm and sustained; but you waver in your judgments, you blame today what you approve of tomorrow, you praise strangers for the smallest work: you appear to have neither plan nor goal, and to crown your levity, you stop your friend in his tracks, and you suspend his blows, when he fights furiously for the salvation of the common cause, in those moments of crisis when the people seem to have nothing more to expect but from their despair. The misplaced but bloody reproaches you make to me in your n. 37, could cause the cause of liberty to lose its most zealous defender, by depriving me of the confidence of a multitude of citizens little in a condition to judge me. It is this fear that reduces me today to the sad necessity of explaining to you the plan of my conduct since the time of the revolution. If you had taken the trouble to follow my course, you would have judged it healthier, and you would have spared me the mortification of telling you myself what should not have escaped you. But before revealing my entire soul to you, I must start by dismissing your charges [he then goes ahead and does exactly that].

And then through another letter inserted in number 196 (August 19) (the response took up seven out of the eight pages):

How I love this beautiful heat, my dear Camille, with which you rise up against me, on the subject of the denunciation of the municipal research committee, published in C'en est fait de nous. It could only spring from a truly patriotic breast: and if it does not suggests a very strong head, it at least announces a very pure heart. Believe the Friend of the People, he is less affected by pain by your accusations against him than he is by happiness by the pleasure of seeing that the image of virtue still finds in you a true adorer. But he cannot bear that you believed him capable of attacking the innocence of one of the members of the research committee, and of outraging the civility in the person of M. Garran de Coulon. I therefore have to enlighten your zeal, and that of the public, who could imagine that by denouncing these gentlemen I had formed the project of depriving the nation of the faithful argus who watch over its salvation. [he then goes ahead and does exactly that] May this useful truth be placed before the eyes of your readers; and believe, dear Camille, that the Friend of the People would not have had to write you this long letter, if he were less jealous of your esteem.

Camille would appear to have been a bit piqued by Marat after that, in number 39 of Révolutions de France et de Brabant (August 23) he writes: ”…it is enough for my readers that I tell the truth with courage, that I seek it in good faith, and I can say that only M. Marat refuses me the first of these qualities, and only those who do not know me who challenge me on the second.” Even so, it’s clear he still viewed Marat as a patriot after the incidence, writing that ”if Marat didn’t exist, it would be neccesary to invent him” (number 61, January 1791) and that ”Marat is the journalist who has best served the revolution” (number 73, April 18 1791), while still calling him out if he thought he had gotten something wrong.

In May 1791 started another controversy between the two, after Marat in number 448 of l’Ami du peuple (May 4 1791) denounced Camille for incorrectly having stated that he was resigning:

Why must the love of my fatherland put my pen against you today? You announce, in your number 73, "that the intrepid Marat, seeing the accusation of Rutteau stifled, seeing the excessive honors which rain on the coffin of Mirabeau, succumbed to discouragement and asks for a passport to exercise the apostate freedom in a less corrupt nation. After leading such a troubled, laborious life underground, he leaves, penniless and poor, which is the best response to his enemies.” You are no doubt basing this on what I exclaimed at the end of my number 339: ”O Parisians! you are so blind, so ignorant, so stupid, so presumptuous, so cowardly, so flat, that it is madness to undertake to recover you from the abyss, that it is madness to undertake to open your eyes my soul, exhausted by useless efforts, is a prey to disgust, that you have inferred my departure.” But if you had bothered to transcribe the following words, you would have seen that I was not leaving, since I say to the Parisians: "I would have abandoned you to your unfortunate fate, if I were not held back by hope to find some virtue in provinces, by the fear of immolate posterity.” You go further, Camille; you want to appear in secret, you announce that I am asking for a passport, and you do not feel that, my head having been put at price by the Austrian cabinet, the general and the other chief counter-revolutionaries, this levity on your part would have exposed me to fall into their hands and become the sad victim of their fury. You can imagine the fate they have in store for me. What to expect from them, except to be thrown into a fiery oven, if they take me in secret, and to be minced by their satellites, if they arrest me publicly? The turn you give to this announcement may not have been dictated by malice, but it is neither less unfair nor less cruel. You make me succumb to discouragement and ask for a passport to practice the apostate of freedom, in a less corrupt nation. But to leave the battle field when the army has laid down their arms, and to abandon the game when there is no more hope, that would be neither a coward, nor a deserter, nor an apostate: that would be yielding to reason, that would be yielding to the imperious laws of necessity! And then, was it the Friend of the People, the only patriotic writer who did not vary for a moment in his principles, his views, his steps, his conduct, that you had to display as an apostate? He, whose courage never wavered in times of crisis, and whose energy increased with the dangers; he, who for twenty-eight months has sacrificed his health, his rest, his liberty to his country; he, who to save her buried himself alive and who for a whole year has defended the rights of the people with his head on the chopping block. Young man, learn that after truth and justice, liberty was always my favorite goddess, that I always sacrificed on her altars, even under the reign of despotism, and that before you knew her name, I was her apostle and martyr [this goes on for another five pages]

Camille gave a short answer in his next number (May 9 1791), apologizing to his readers for printing it in his journal, which should be dedicated to solely public affairs. This is also the first time any of them is proven to have used tutoient with the other.

It seems that in my number 73 there is a gross misprint, ”to exercise the apostate” instead of ”to exercise the apostolate,” although the remaining numbers say the apostolate. Both the language and the meaning of the sentence indicate that it should be read apostolate, because in this sentence I praise Marat for his constancy. However, for this Marat addresses me eight pages of insults. Listen Marat: I only recommend that you don't allow yourself quite so much of Gauthier's example, and that you slander a little less, even the people in place. As for me, I allow you to say as many bad things about me as you want. You write in an underground where the ambient air is not suited for cheerful ideas, and can make a Timon of a Vadé. You are right to take the step of seniority over me, and disdainfully call me ”young man,” since it is 24 years since Voltaire made fun of you; to call me unjust, since I have said that you were the one of all the journalists who has served the revolution the best; to call me malevolent, since I am the only writer who has dared to praise you; finally, to call me a bad patriot, since there has slipped into a few numbers a misprint so gross that no one can mistake it. In vain you insult me, Marat, as you have been doing for six months, I declare to you that as long as I see you extravagant in the direction of the revolution, I will persist in praising you, because I think that we must defend freedom, like the city of Saint-Malo, not only with men, but with dogs.

Marat was however not satisfied with that, but wrote another long letter published two days later in number 455 of l’Ami du Peuple. He continued to use vouvoiement when adressing Camille:

Despite your joviality, Camille, you do not always have the art of getting angry with grace and dignity. Surprised to see you relatively unaffected by the dangers of the fatherland that you give your readers, in a time of crisis, several numbers of table of contents, or talk to them about your hassles with Malouet, Desmeuniers, Naudet, Desessart, and not very jealous of your honor to thus help your enemies to make believe that you were in business, I tried to call you back to order. This little freedom earned me the pretty note that ends one of your February 1791 issues. Pained to see you involuntarily discrediting my paper, and so inconsiderately harming public affairs, I have sent you a few light reproaches. You only rejected my friendly representations by qualifying them as insults, and by attributing them to the mephitic air of my cellar: I could ask you if you acted in this way so as not to contradict the proverb which claims that truth is the only offense; but I prefer to observe you than to show so much humor, when I show so little of it, it is wrong to take advantage of your advantages, you whom nature has made so gay, so witty, so amiable, you who breathe such pure air, you who have such a good cellar, you who are surrounded by so many charming objects. [This goes on for another three pages, you get the idea at this point].

When Camille along with Fréron in 1792 started a new paper, La Tribune des Patriotes, they unsuccessfully tried to get Marat to join in on the project too — ”We would have wanted Marat to fight with us on the same side, in order to oppose this trio of glorious confessors of the revolution, to the academic trio of Mr. Pankouke, or to this myriad of wealthy names with which Nicolas Bonneville adorns the frontispiece of his Chronicle du mois, but Marat replied proudly: The eagle always goes alone, and the turkey in a herd.” He still wanted to help with the journal, on May 19 we find the following letter from him to Camille:

The enemies of the fatherland having again placed me under the sword of tyranny, I send you two letters which I ask you for a place in the first issues of Tribune des Patriotes. As it is an important for liberty that journalists who betray its cause are unmasked, I hope that you will attach some value to it. They are signed by me, to put you in order in any case. I salute you patriotically, as well as Fréron, your colleague and mine.

Marat, the friend of the people.

May 19 1792.

Camille claimed to have been at the house of ”the poor Marat” right after the murder and there have overheard Legendre ask Charlotte Corday if she was the one who had come to his place earlier that day with the intention to kill him too. An question which Camille made fun of not long after, writing that ”a woman who had come to kill the first man of the Mountain wouldn’t prioritize [Legendre].”

We don’t know what Camille’s immidiate reaction to Marat’s death was, however, on July 22 1793, nine days after the murder, the Jacobin Club tasked him, together with Robespierre, Lepeletier and Dufourny, with writing an adress to the French people regarding it. Said adress was printed and read aloud at the club four days later, obviously deploring of the event and praising Marat.

None of the texts written by Camille after Marat’s death is much of a gold mine when it comes to telling us more about their relationship. Camille mentions his name four times in his Lettre à general Dillon and 34 times in the Vieux Cordelier, always praising him or using him as a political card. He also mentioned him four times in his defence, hoping Marat’s memory could help him save his life:

Who denounced Dumouriez the first, and before Marat and more vigorously than anyone else? Surely one cannot deny that it was me? […] This Vadier, president of the Committee of General Security, is the same Vadier that Marat denounced in his number from July 17 1791, as the most infamous of traitors and deserters: these were the words he used.

#two grown men arguing over a typo…#this is why aliens haven’t visited us#jean paul marat#camille desmoulins#marat#desmoulins#ask#long post#frev friendships

36 notes

·

View notes

Note

At risk of being controversial i believe I found the best parallels between the Abrahamic religions and the nations of Scandinavia. The Swedes are the Christians of Scandinavia, the Norwegians are the Muslims of Scandinavia, and finally the Danes are the Jews are Scandinavia. Feel free to rearrange though

As a follow up to blow people's minds. Canada is the Norway of North America. The United States is the Sweden of North America. Mexico is the Denmark of North America.

none of these analogies make any sense. islam and christianity aren't ethnic groups. arabic and hebrew are much less closely related than any north germanic langauges. there is no norwegian hegira. there's never been a kalmar union of north america. and scandinavia was never colonized by outside powers.

norway has oil, and so does the arabian peninsula, so maybe a vague norway-arab analogy there...? but arabs aren't synonymous with muslims. and the big viking conquests didn't originate only in norway.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Very Scandalous Astrolabe

Posting these (very raunchy) images got my Twitter account suspended. So only the deviants on Tumblr can enjoy sexy astrolabe action

This small astrolabe carries four tympanums for latitudes 24°/30°, 31°/35°, and 32°/36° (corresponding to Persia), and for latitude 0° (i.e., the circle of the equator) and 66°. There is an alidade and a rete. The back of the mater displays a lunar calendar, in accordance with Islamic use, a shadow square, and a quadrant. The instrument is dated 496 of the Hegira (1102-1103 of the Christian era) and is signed by its maker, Muhammad 'Ibn Abi'l Qasim 'Ibn Bakran, on whom we have no information

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Hegira” (1988) by Alan Gutierrez via ImaginaryMonuments

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ali ibn Abi Talib - World History Encyclopedia

https://www.worldhistory.org/Ali_ibn_Abi_Talib/

View On WordPress

#601#632#Abu Bakr#Abu Talib ibn Abd al-Muttalib#Ahl al-Bayt#Aisha#Ali ibn abi-Talib#Asad Allah#Bab ul-Ilm#Clan of Hashim#Event of Ghadir Khumm#First Fitna#Fourth Caliph#Hasan#Hegira#Hussayn#Imams#Islam#Kaaba#Kharijites#Mawla#Mecca#Medina#Muhammad#Rashidun Caliphate#Shi&039;ism#Shia#Sunni#Talhah#Umar

1 note

·

View note

Text

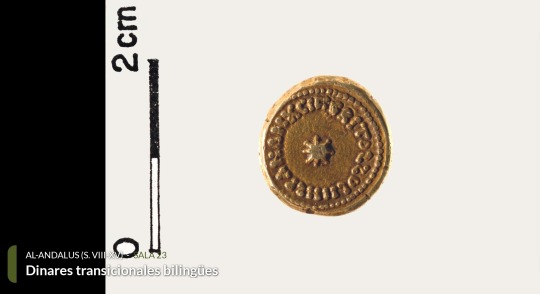

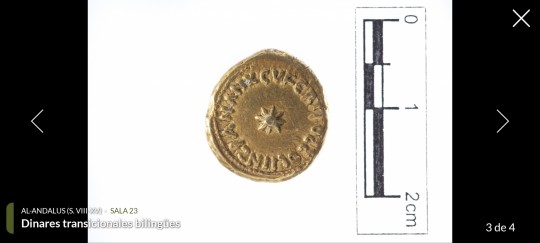

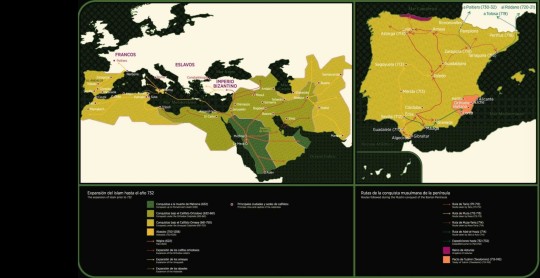

Also related with the second part of the bookscans, I would like to add some pictures of the first gold dinars of Al Andalus, the transitional coins during the conquest of the Iberian Peninsula. They are from the years 712/713 (94 of Hegira) and 716/717 (98 of Hegira), the first ones have Latin characters, but the last ones are bilingual, and are in both Arabic and Latin:

These are from the Al-Andalus' section of the Spanish National Archaeological Museum, concretely I got the pictures from the museum's free app (the app is mainly a virtual tour inside the museum that offers a close-up of the exhibits)

Bonus track: A map of the conquest

#al andalus#book scans#al andalus history#al andalus. historical figures#al andalus personajes históricos#historyblr#bookscans related#spanish history#coins#dinar#8th century#arqueology

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

hegira

49 notes

·

View notes

Note

Dictionary page 1224?

Aha, here now we're in the A's of the Customary Abbreviations section

Let's see, what do we have?

A.H. in the year of the Hegira, A.D. 622 (L. anno Hegirac).

a.h.l. at this place (L. ad hunc locum).

a.m. before noon (L. ante meridium).

A.M.I.C.E. Associate Member of the Institute of Civil Engineers

A.O.D. Ancient Order of Druids, Army Ordinance Department

A.O.S. Ancient Order of Shepherds

A.R.S.W. Associate of the Royal Scottish Society of Painters in Water Colours

A.S.L.I.B. Association of Special Libraries and Information Bureaux

A.S.R.S. Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants

--

I am fully imagining all of those societies like. working together on something? Both AOD's causing some confusion (someone who belongs to both?) - something very much to do with maps in some manner, I think. And sheep. And painting Scotland?

Taking the train. With an army map druid. Who has a watercolour painting from a Special Library archive. To go see a shepherd. About something that happened a.h.l. A.H.? Tho I don't think we'll get there a.m.

What is the Hegira anyway? Aha, it's when the prophet Mohammed left Mecca for Medina (page 471, listed between hegemony and heifer, if you're interested). From Arabic hijrah meaning flight, says here.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Durbar of Emperor Akbar Shah II. Though not the emperor described below, Akbar Shah II is depicted here as the central figure of society and with quasi-religious symbolism, much as his ancestor Jalaluddin Akbar Azam is described below.

Emperor Akbar and the Ambiguous Use of Ascribed Divinity in Mughal Rulership

It is typical that when [Akbar] did finally decide on his own religion it should turn out to be so generalized, its main distinguishing feature being a vague nimbus of divinity around his own person, and that he should have made so little effort to spread it beyond his own circle of friends. The announcement in 1582 of this new religion, known as the din-i-Ilahi or 'religion of God', [...] seemed to [...] present himself as simply divine.

The din-i-Ilahi, Akbar's new religion based on a vague and mystical liberalism, was at the very best unspecific about how far Akbar straddled the dividing line between mortal and divine. [... I]n 1584 he rejected the Muslim system of dating events from the Hegira, or flight of the prophet from Mecca to Medina, and replaced it with a new chronology beginning with his own accession. [...] The new chronology dating from his own accession was known as the Divine Era.

And considerable outrage was caused when he decided to stamp on his coins the potentially ambiguous phrase Allahu akbar; the ambiguity derives from the fact that akbar means great as well as being the emperor's name so that the words could mean either 'God is great' or 'Akbar is God'. This has seemed to various modern historians to be the most blatant assumption of divinity, but it need not have been so. When a shaikh accused Akbar of having intended the second meaning he replied indignantly that it had not even occurred to him. His claim sounds far-fetched; and the fact that he had taken the unusual step of removing his own name and titles from his coins, in order to substitute this phrase, suggests that he was not unaware that it included his name as well as God's. But Allahu akbar is a basic Islamic incantation. It is a central phrase in worship and prayer, but it is also used as a lament in grief and, at the other extreme, as an exclamation of triumph or defiance (it was, for example, the the battle cry of Timur's troops). So it seems likely Akbar was amused by the ambiguity rather than taking it as a serious statement of his own identity.

[...]

To the very end of Akbar's life —so inconclusive had the din-i-Ilahi proved— each religious group still had hopes of the emperor and there was eager competition in 1605 to discover whose God would be would have the honor of being the last on his lips. Even this was uncertain, most of the Christians believing him to have died a Muslim, and many of the Muslims a Hindu.

[...]

Akbar's progression away from orthodox Islam towards his own vague religion was no doubt part of a conscious effort to seem to represent all his people —the Rajputs, for example, saw their rajas like Abul Fazl's image of Akbar, both human and divine— and it fitted in with a general policy which included his adoption of Hindu and Parsi festivals and his increasing abstinence from meat in the manner of Hindus. But it also fulfilled a personal need. He was drawn to mysticism, fond of lonely contemplation, eager for any clue to the truth, and if that truth should touch him with divinity, there was always precedent within the family; Humayun had indulged in a mystical identification of himself with light, and through light with God; Timur, more conventionally, used to refer to himself as the 'shadow of Allah on earth'. Akbar's religious attitudes seem to have been a happy blend of personal inclination and sure policy.

- Bamber Gascoigne (The Great Moghuls, pages 105, 108, 108-109, 106, 109-110)

4 notes

·

View notes