#Little Big Horn

Text

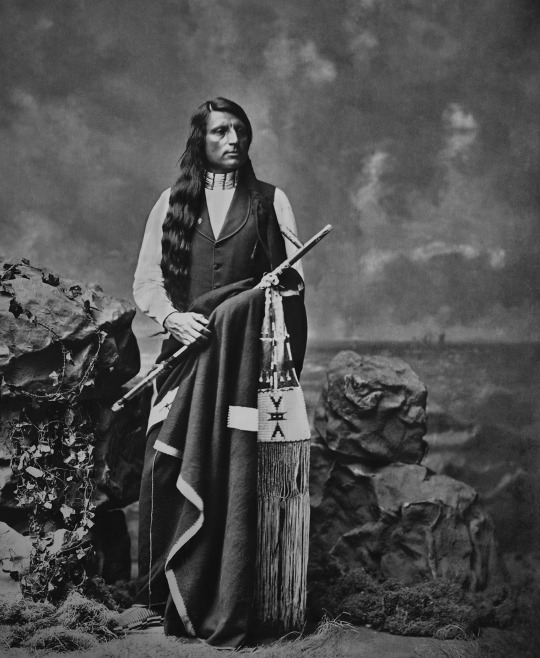

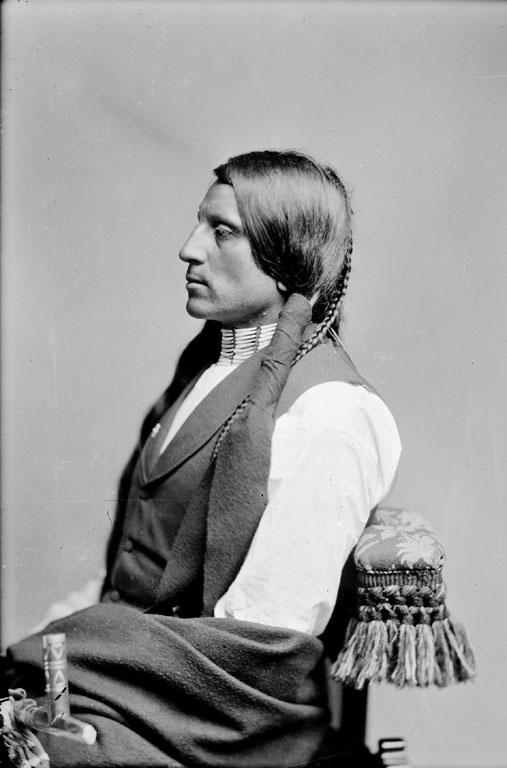

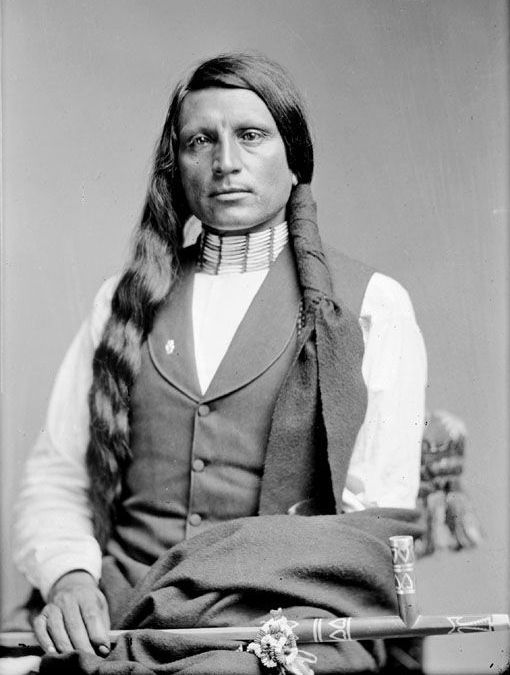

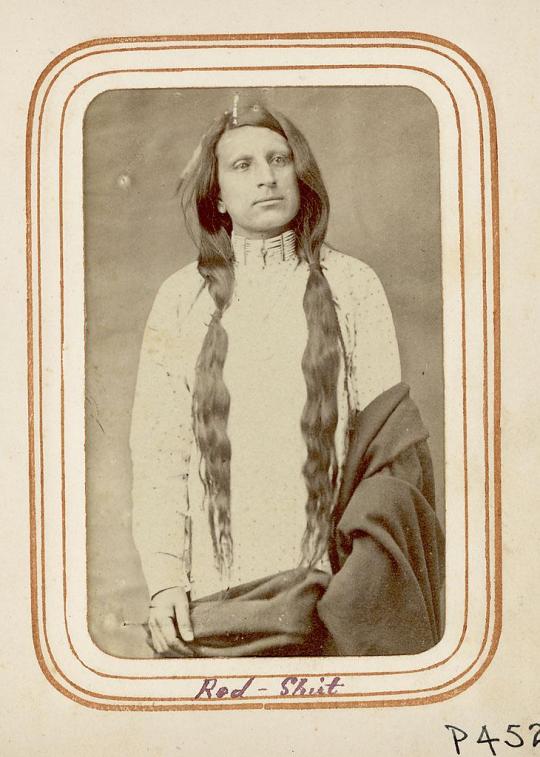

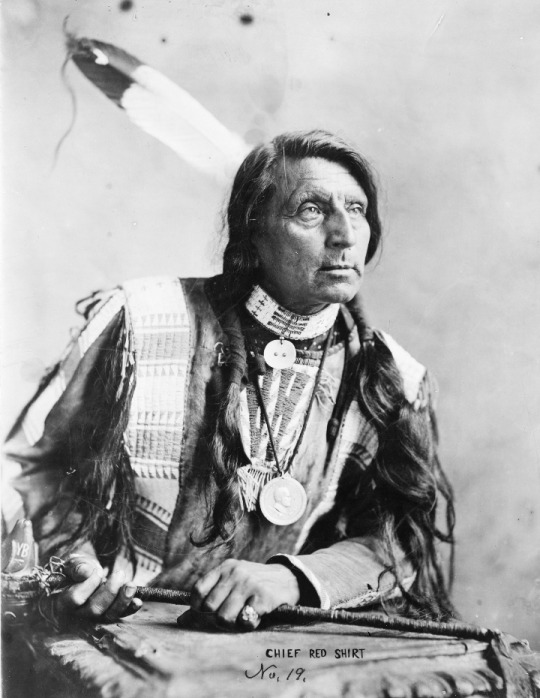

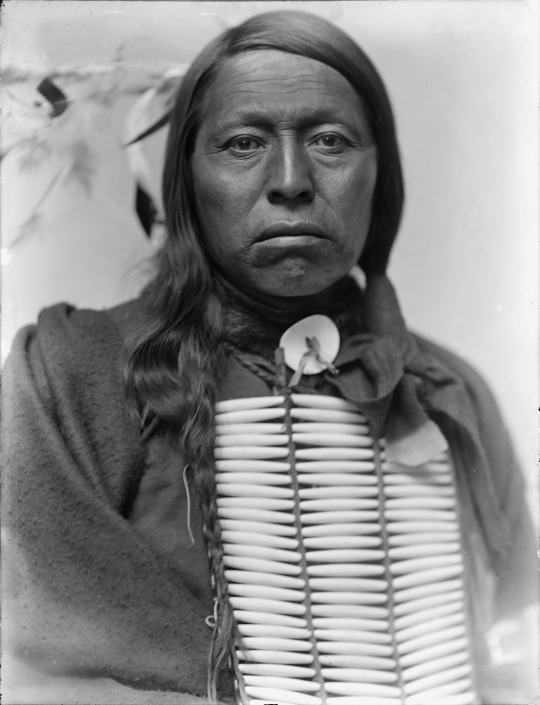

⚞Chief Red Shirt⚟

Chief Red Shirt - Oglala Sioux

Red Shirt (Oglala Lakota: Ógle Ša in Standard Lakota Orthography) (1847–1925) was an Oglala Lakota chief, warrior and statesman.

Chief Red Shirt camped with Crazy Horse and the rest of the Oglala at the Little Big Horn. The Oglala camp was next to the Cheyenne camp near the bottom of what is now known as Last Stand Hill. Red Shirt supported Crazy Horse during the Great Sioux War of 1876-1877 and the Ghost Dance Movement of 1890, and was a Lakota delegate to Washington in 1880.

Dakota delegation to Washington, D.C., Left to right, Red Dog, Little Wound, John Bridgeman (interpreter), Red Cloud, American Horse and Red Shirt. June, 1880

Chief Red Shirt wore his hair to represent peace and war. One side of his hair was wrapped to indicate he was ready for peace, the other side was worn loose indicating his readiness for war. This was done when he traveled with Chief Red Cloud to Washington D.C.

Red Shirt surrendered with Crazy Horse in 1877. After the surrender he moved to an area that is now known as Red Shirt, SD. Red Shirt was one of the first Wild Westers with Buffalo Bill's Wild West and a supporter of the Carlisle Native Industrial School. Red Shirt became an international celebrity Wild Westing with Buffalo Bill's Wild West and his 1887 appearance in England captured the attention of Europeans and presented a progressive image of Native Americans.

Red Shirt in Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show

On March 31, 1887, Chief Red Shirt, Chief Blue Horse and Chief American Horse and their families boarded the SS State of Nebraska in New York City, leading a new journey for the Lakota people when they crossed the ocean to England on Buffalo Bill's first international to perform at the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria and tour through Birmingham, Salford and London over a five–month period. The entourage consisted of 97 Indians, 18 buffaloes, 2 deer, 10 elk, 10 mules, 5 Texas steers, 4 donkeys, and 108 horses. Buffalo Bill treated Native American employees as equals with white cowboys. Wild Westers received good wages, transportation, housing, abundant food and gifts of clothing and cash from Buffalo Bill at the end of each season.

Photo from London - Red Shirt was lionized by the British press and his handsome features and stately bearing caused reporters to hang on his every word. Queen Victoria adored Chief Red Shirt and reportedly said after meeting him, "I know a real prince when I see him."

William F. "Buffalo Bill" Cody, Rosa Bonheur, Chief Rocky Bear, Chief Red Shirt, William "Broncho Bill" Irving, Roland Knoedler, and Benjamin Tedesco in front of Cody's Tent at the Paris Exposition Universelle - 1889

Another photo of Red Shirt - this time with Cody's company somewhere in Italy, 1890. Front row: No Neck, Rocky Bear, Black Heart, Georgie Duffy, Cody, Bessie Farrell, Annie Oakley, Red Shirt. Others in back row: Buck Taylor (fifth from right), Johnny Baker (fourth from right), Carter Couturier, advertising agent(?) (second from right), Has No Horses (far right)

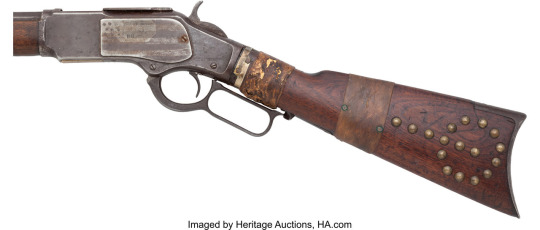

Chief Red Shirt's rifle & scabbard.🔼 - Details 🔽

Chief Red Shirt was a Wild Wester for over thirty years - St. Louis World's Fair, 1904.

Chief Red Shirt (Ógle Ša) - 1847–1925

#indigenous#Sioux#native american#red shirt#Chief Red Shirt#buffalo bill#queen victoria#crazy horse#Little Big Horn#Oglala#ghost dance movement#lakota sioux#lakota#ogle sa#wild wester

299 notes

·

View notes

Video

Wild horses by ucumari photography

Via Flickr:

We saw a few "packs" of wild horses while visiting this somber park. Read more about the battle here: Little Big Horn Battlefield

#ucumari photography#Little Big Horn#Battlefield#National#Monument#wild#horse#foal#animal#mammal#Montana#September#2022#DSC_8188#flickr

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

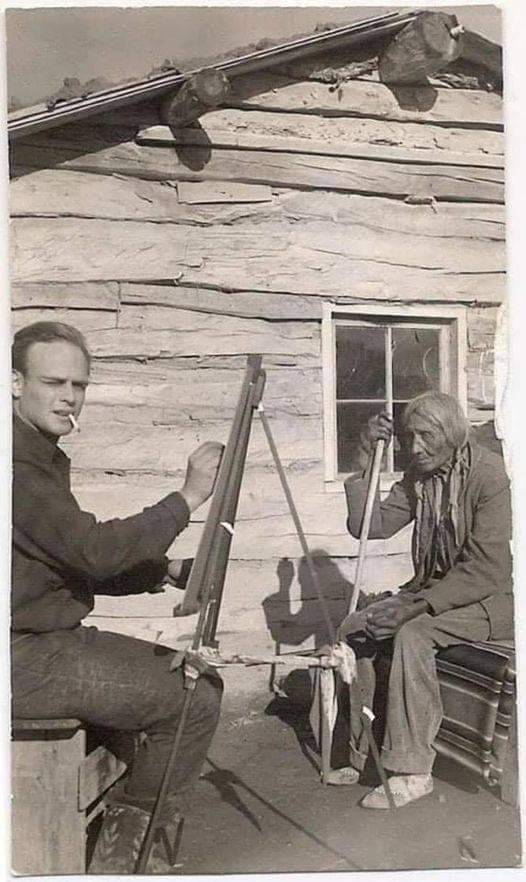

Joseph White Cow Bull (Cheyenne) being painted by Artist David Humphreys Miller. Circa 1938. White Cow Bull was a survivor of the Battle of a Little Big Horn.

Mr Miller found 72 survivors of the battle. He learned their language, 13 in all, and ended up painting all 72. He also collected their stories and wrote a book, “Custer’s Fall, The Indian side of the Story.”

He also wrote a book called “Ghost Dance” about Wounded Knee.

While talking to Joseph White Cow Bull, he was told what happened during the battle. White Cow Bull never said he shot Custer, but from the description of the battle, the Horse the rider was on and corroboration from the others he spoke to, he determined it was Joseph White Cow Bull that shot Custer early in the fight. The horse the rider was on had 4 white stockings, and Custer’s horse was the only horse with those markings.

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

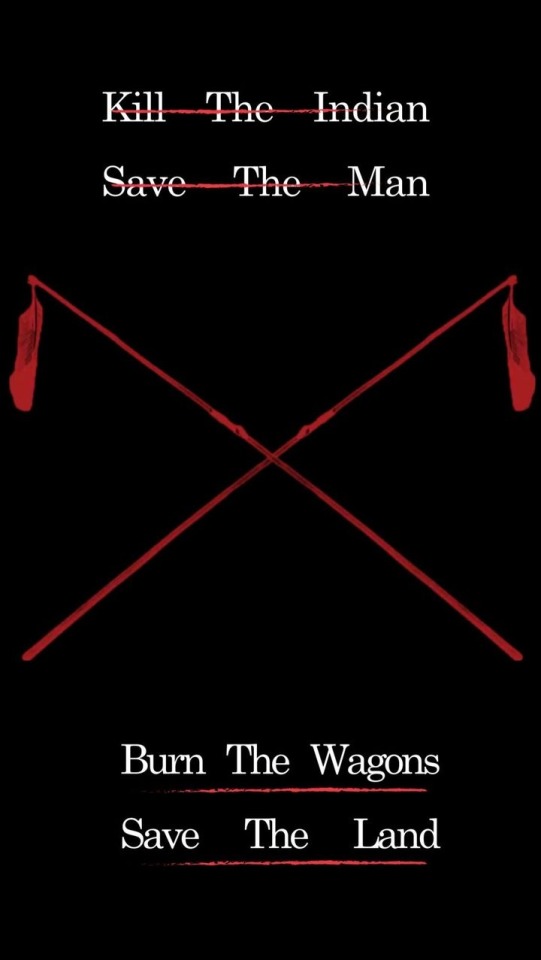

From @JoeCrowShoe

#burn the wagons#save the land#land defender#water defender#landback#aim#crazy horse#Tasunke Witco#greasy grass#little big horn#Custer died for your sins#tecumseh#zapata#Geronimo#john trudell#Leonard Peltier#free Leonard Peltier#climate change#ohlone territory

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tim Johnson — Little Big Horn (synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 1988)

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

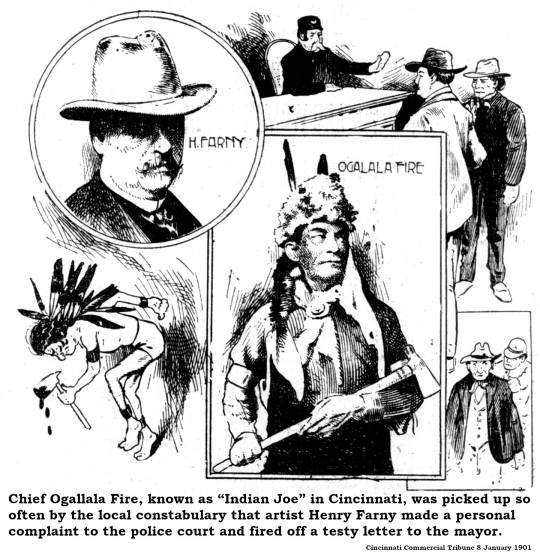

He Fought At Little Big Horn And A Cincinnati Artist Made His Face Famous

In Cincinnati, everybody called him Joe, mostly. Or Indian Joe if they needed to distinguish him from all the other Joes wandering around the Queen City. He wasn’t young when he arrived in town, at least 70 years old, though he stood straight and tall. He was muscular enough to wrestle a bear onstage at the Kohl & Middleton Dime Museum on Vine Street.

That’s where Henry Farny found him. Farny was a famous artist, renowned for his paintings depicting life among the Native American tribes of the Old West. He sold canvases as fast as he could turn them out and might have been wealthy if he hadn’t been so focused on giving away his money. A memorial after Farny’s death [Enquirer 31 December 1916] summed up the artist’s well-known generosity:

“Anybody down and out had a friend in Farny. It was always the under dog, the one whose strength and fortune were less happy than others, that Farny’s broad mind and heart would give assistance to.”

Farny had made several trips out west, capturing the last fading echoes of the life surrendered by Native Americans under the onslaught of European expansion. His friends claimed Farny was fluent in the Sioux language, but he was at least proficient enough to understand simple conversations. One evening, Farny and fellow artist Martin Rettig attended a show at a local theater. On stage, a family of Sioux performed traditional dances and demonstrated their skill at various crafts. When the father of the family stood to give a speech, Farny leaped out of his seat in outrage. Farny gathered that the Sioux family had a complaint against the government and the unscrupulous manager assured them he would see that they got an audience with the U.S. President. In preparation for the presidential visit, the manager told the family they needed to attend several “receptions” at a series of vaudeville theaters along the way. Farny heard the Father say he was tired of these receptions and would he ever see the President? On Farny’s insistence, the family was given passage home and their “manager” split town.

When Farny saw Indian Joe wrestling that bear for another shady impresario, he got Joe out of that contract and into a job as janitor at the Cincinnati Art Club on Fourth Street. In those days, a janitor was not only a custodian and cleaner, but also what we would call a building superintendent today. The Art Club offered generous flextime and Joe could take off for weeks at a time if a decent vaudeville gig came around.

Farny also learned Joe’s real name, or at least the English translation of it. He was Chief Ogallala Fire, and there hangs a tale. Ogallala Fire was born sometime around 1826 and spent most of his life fighting white settlers encroaching on Sioux lands. According to the Chicago Tribune [3 January 1916]:

“In the days of Indian warfare, Chief Ogallala Fire was known as one of the bravest warriors of the Sioux. History relates that he led his warriors in many raids on white settlements in Wyoming and once defied a detachment of United States soldiers who trapped him in the mountains for two months [until he] finally escaped.”

Ogallala Fire was almost 50 when General George Armstrong Custer led an army against the Sioux in 1876. The expedition ended with Custer and his entire battalion slaughtered at Little Big Horn. Ogallala Fire spent the rest of his life not only claiming participation in that battle, but that he himself had killed Custer in hand-to-hand combat. He certainly had battle scars consistent with a life as a warrior. According to the Chicago Tribune:

“In ‘Custer’s Last Fight’ Chief Ogallala Fire received two bullets, was slashed across the head with a saber in the hands of an officer, and was pinned to the ground from a bayonet thrust through his shoulder by a soldier.”

After that battle, Chief Ogallala Fire resigned himself to life on a reservation and might have stayed there the rest of his life had not show business come calling. Charles A. Eastman, an American Indian physician known as Ohiyesa among the Dakota Sioux, recalled meeting Ogallala Fire:

“In 1892, I scarcely believed that he would ever leave the reservation, but in his latter days he was caught by the white man's vices, the love of money and the desire for ‘fire-water,’ coupled with the old habit of wandering. He traveled in this country and abroad with Buffalo Bill.”

After a triumphal engagement at the Chicago World’s Fair, Ogallala Fire hit the road with Buffalo Bill and other Wild West shows, eventually settling into the bear-wrestling act that brought him to Cincinnati. Whether his thirst for liquor was any stronger than the average Cincinnatian is a matter of dispute, but Ogallala Fire was occasionally arrested for public drunkenness here. He was also arrested frequently just because the police were looking for someone who looked like an Indian and he fit the bill. This harassment repeated so often that Farny, weary of getting his innocent friend released, fired off a testy note to the mayor.

One day, when Ogallala Fire had been on the road with one of the Wild West shows, Farny hosted several friends in his studio. They heard some strange chanting rising from the nearby stairwell. According to the Enquirer [31 December 1916]:

“Farny, after listening for a few seconds, with sparkling eyes, grabbed a tom-tom, and, beckoning his friends to follow him, began to dance in true Sioux fashion around the large studio, all the time beating the tom-tom. The music outside grew stronger and stronger until the door was swung wide open and an Indian appeared beautifully garbed. He leaped into the room and dancing like mad with occasional shrieks of joy thus expressed his delight over his reception. It was Joe, as the tribe called him, ‘Ogallala Fire,’ the old favorite Sioux model of Farny’s whom he had not seen then for a long time. Farny was indeed glad to have him again, a fact accentuated by the gold piece he bestowed upon him immediately.”

Farny painted multiple portraits of Ogallala Fire and incorporated his likeness into dozens of other paintings. Other Cincinnati artists including John Hauser also employed him as a model. As the Wild West shows faded in popularity, Ogallala Fire found work in the nascent motion picture industry, appearing in several early silent films.

It was the Chicago Feature Film Company, shooting an “oater’ with b-list actress Lily Branscomb that brought Ogallala Fire to Chicago around 1914. He ended up staying there at the home of a granddaughter. One day, after a long illness, he asked for a razor and sliced his throat. Despite medical intervention Ogallala Fire died, aged 90, a week later. The old chief once told Charles A. Eastman/Ohiyesa:

“Friend, I have engaged in more than 100 battles, but never have I been bewildered except when I entered a city of the white man. There my spirit is lonesome, as it never was on the uninhabited prairie. The people seem to me more like bears and wolves.”

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

#question everything#history#ancient#ancestors#art#buffalo#native american#american indian#indian headdress#sioux empire#lakota#teepee#little big horn#sitting bull#geronimo with us ‘in spirit’ and i’ll never give up fight to clear his name#crazy horse#greasy grass#you can’t eat money#ghost dance

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

#1970s tv#70s movies#little big man#native#human beings#miss pendrake#little big horn#native american#life#sinful life#no fun

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shield by He Nupa Wanica/Joseph No Two Horns

Currently on display as part of the MET’s Art of Native America exhibit, this type of shield would have been carried into battle; it’s vision-inspired imagery offered spiritual protection. Joseph No Two Horns was one of the most prolific Plains artists and his artwork helps to identify the tribal history of the Lakota. His work depicts specific events in his own life as well as the lives of other Lakota people. A warrior by the age of fourteen, No Two Horns participated in at least 40 battles during his life, including the Battle of Little Big Horn. No Two Horns also kept his tribe’s winter count, a collection of pictographs recording 137 years of Lakota history.

Article on Joseph No Two Horns, American Indian Art Magazine, 1993

More information

0 notes

Text

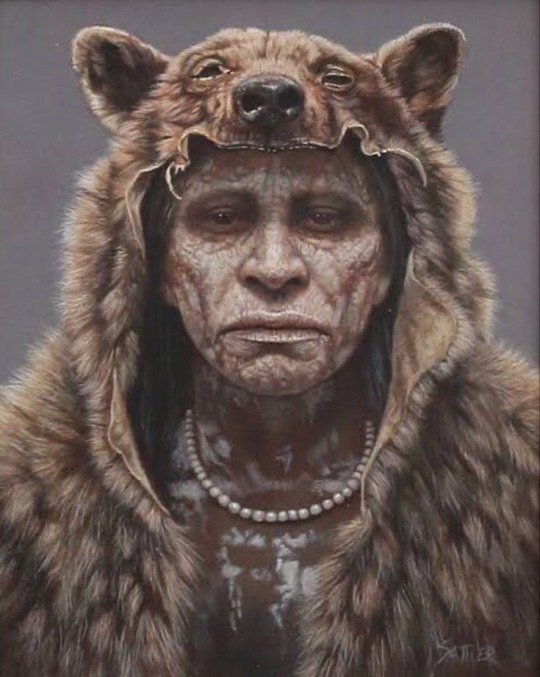

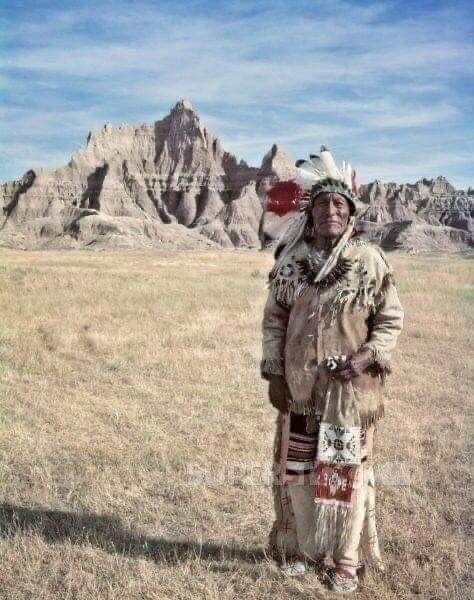

Flying Hawk

Flying Hawk, also known as Moses Flying Hawk; March 1854 – December 24, 1931) was an Oglala Lakota warrior, historian, educator and philosopher. Flying Hawk's life chronicles the history of the Oglala Lakota people through the 19th and early 20th centuries, as he fought to deflect the worst effects of white rule; educate his people and preserve sacred Oglala Lakota land and heritage.

Chief Flying Hawk was a combatant in Red Cloud's War and in nearly all of the fights with the U.S. Army during the Great Sioux War of 1876. He fought alongside his first cousin Crazy Horse and his brothers Kicking Bear and Black Fox II in the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876, and was present at the death of Crazy Horse in 1877 and the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890.

Chief Flying Hawk was one of the five warrior cousins who sacrificed blood and flesh for Crazy Horse at the Last Sun Dance of 1877. Chief Flying Hawk was the author of his commentaries and accounts of the Battle of the Little Big Horn, Crazy Horse and the Wounded Knee Massacre, and of Native American warriors and statesmen from who fought to protect their families, defend the invasion of their lands and preserve their culture. Chief Flying Hawk was probably the longest standing Wild Wester, traveling for over 30 years throughout the United States and Europe from about 1898 to about 1930. Chief Flying Hawk was an educator and believed public education was essential to preserve Lakota culture. He frequently visited public schools for presentations. Chief Flying Hawk leaves a legacy of Native American philosophy and his winter count covers nearly 150 years of Lakota history.

#historic photographs#chief flying hawk#lakota#sioux#little big horn#crazy horse#kicking bear#flying hawk#oglala lakota

170 notes

·

View notes

Video

Wild horses by ucumari photography

Via Flickr:

We saw a few "packs" of wild horses while visiting this somber park. Read more about the battle here: Little Big Horn Battlefield

#ucumari photography#Little Big Horn#Battlefield#National#Monument#wild#horse#foal#animal#mammal#Montana#September#2022#DSC_8188#flickr

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Everyday 🙌🏽

#it’s a good day to be indigenous#hokahey#ghost dance#sitting bull#lakota#hunkpapa#greasy grass#crazy horse told y’all#crazy horse#turtle island#Custer’s last stand#little big horn#disobey#artist unknown#land back#modern art#hookah at

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crow Fair 2002. Little Bighorn River AKA Greasy Grass. Crow Fair is "the teepee capital of the world, over 1,500 teepees in a giant campground," according to 2011 Crow Fair General Manager Austin Little Light. The Crow Fair was created in 1904 by Crow leaders and an Indian government agent to present the Crow Tribe of Indians as culturally distinct and modern peoples, in an entrepreneurial venue. It welcomes all Native American tribes of the Great Plains to its festivities, functioning as a "giant family reunion under the Big Sky." Indeed, it is currently the largest Northern Native American gathering

1 note

·

View note