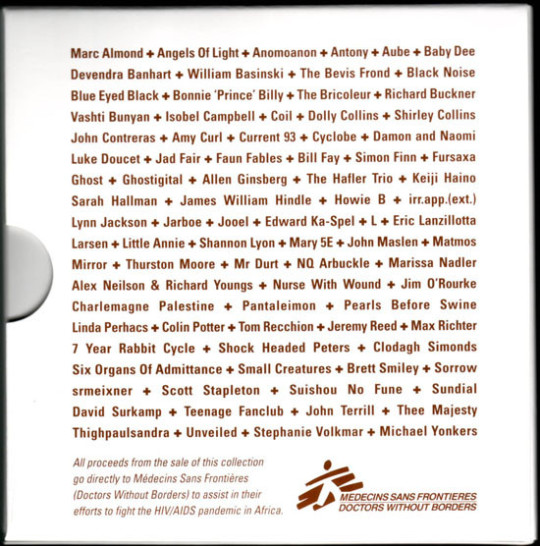

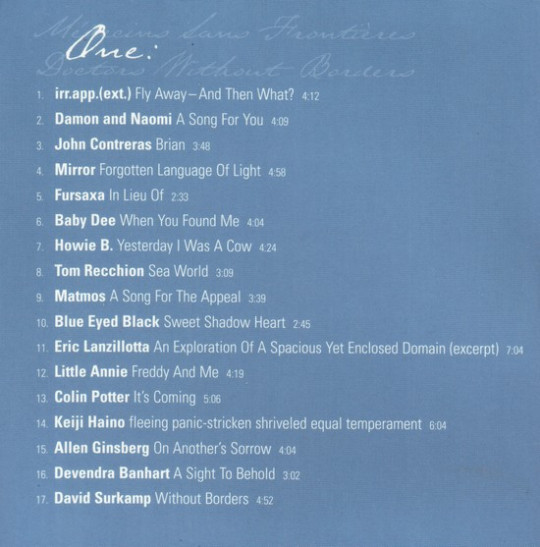

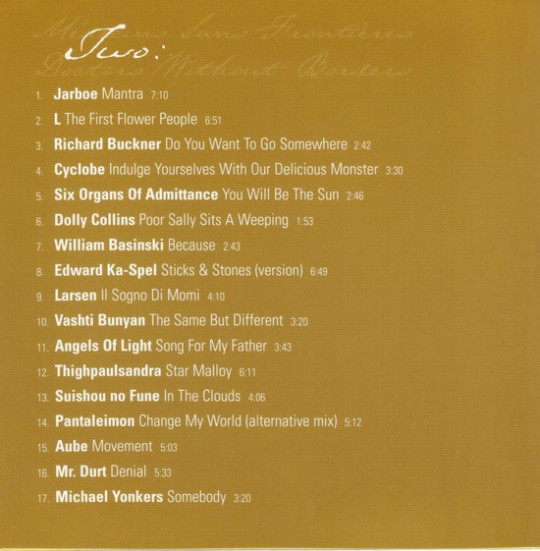

#Not Alone - Médecins Sans Frontières - Doctors Without Borders

Photo

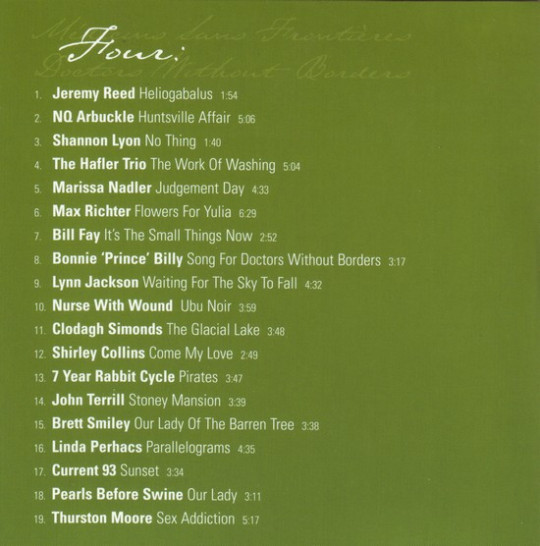

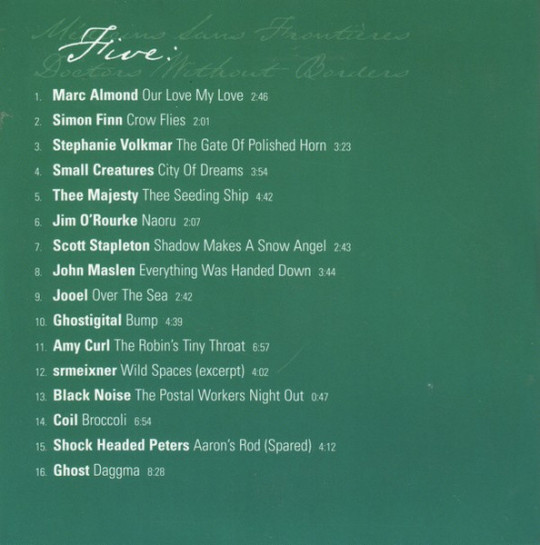

Album Art for

VA - Not Alone - Médecins Sans Frontières - Doctors Without Borders (Durtro, Jnana, 2006)

Discogs

#album art#album covers#cover art#Not Alone - Médecins Sans Frontières - Doctors Without Borders#compilation#Durtro#Jnana#2006

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

source

"The US veto makes it complicit in the carnage in Gaza," said Avril Benoît, executive director of MSF-USA.

Today, December 8, the United Nations Security Council failed to adopt a resolution demanding a ceasefire in Gaza—blocked by a veto from the United States. The Security Council held an emergency meeting to discuss the humanitarian catastrophe in Gaza. This followed a letter from the UN Secretary-General invoking Article 99 to call on the Security Council to prevent further escalation and end this crisis. In addition to demanding an immediate humanitarian ceasefire, the draft resolution tabled by the United Arab Emirates reiterated the Security Council's demand on all parties to comply with their obligations under international law, notably with regard to the protection of civilians in Palestine and Israel.

Avril Benoît, executive director of Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) USA gave the following statement:

“As bombs continue to rain down on Palestinian civilians and cause widespread destruction, the US has once again used its power to block an attempt by the UN Security Council to demand a ceasefire in Gaza. By vetoing this resolution, the US stands alone in casting its vote against humanity.

The US veto stands in sharp contrast to the values it professes to uphold. By continuing to provide diplomatic cover for the ongoing atrocities in Gaza, the US is signaling that international humanitarian law can be applied selectively—and that the lives of some people matter less than the lives of others.

Israel has continued to indiscriminately attack civilians and civilian structures, impose a siege that amounts to collective punishment for the entire population of Gaza, force mass displacement, and deny access to vital medical care and humanitarian assistance. The US continues to provide political and financial support to Israel as it prosecutes its military operations regardless of the terrible toll on civilians. For humanitarians to be able to respond to the overwhelming needs, we need a ceasefire now.

The US veto makes it complicit in the carnage in Gaza.”

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

RULES. repost, don’t reblog

TAGGED. @lokitheliesmith {{mahalo! my dearest}}

TAGGING. Be Fae, steal memes

BASICS.

FULL NAME. Elizabeth Irene Riley (birth certificate: Elikapeka Ailine Alohaekaunei kahanuola'Ilikea'wahine Riley )

NICKNAME. Beth

BIRTHDAY. 28 June

ETHNIC GROUP. Pacific Islander {Rokea Kinfolk}

NATIONALITY. American {{Sovereign Kingdom of Hawai’i}}

LANGUAGE. Beth is fluent in: Hawai’ian Pidgin {her language of choice}, English, Latin. She’s conversational in: Japanese, Russian, Italian, French, Mandarin and Cantonese. She can speak some: (modern) Greek, occasional Spanish, Romanian, some Gaelic. She made a point of learning Kikongo, Masalit, and Beria (the first a language of the Democratic Republic of Congo, the later two spoken in Darfur, where she spent time serving with Médecins Sans Frontières {Doctors without Borders}

SEXUAL ORIENTATION. Demi-sexual, quoiromantic {{your guess is as good as hers}}

RELATIONSHIP STATUS. n/a

CLASS. 1% Wealthy/Upper class, {{Ali’i class}}

HOME TOWN / AREA. Honolulu, O’ahu, Hawai’i

CURRENT HOME. Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, New York

PROFESSION. ER Nurse, technically has an MD but dropped out during her residency.

PHYSICAL.

HAIR. Rich dark brown, shoulder length-to mid back. Thick, soft, professionally styled.

EYES. Green/brown hazel {heterochromia}, naturally thick lashes.

NOSE. Small, straight. crinkles at the corners of her eyes when she genuinely smiles

FACE. Delicate features, high cheek bones, wide eyes, clearly bi-racial

LIPS. Soft, full lower lip, perfectly shaped upper cupid’s bow.

COMPLEXION. Tawny brown/olive tone, a “warm” autumn, with red and yellow tints to skin and hair. Beth, being half Irish and half Polynesian falls under “ambiguously ethnic” and depending on style choices and sun exposure can range from almost a light complexion to deeply tan.

BLEMISHES. She has a fine little series of freckles around her mouth and across the bridge of her nose. Someone would have to look close to even notice them. There are the occasional freckles on her shoulders and down her back, as well.

SCARS. Shark Bite from just above her ankle, to just below of her knee of her left leg. The scar is deep, the muscle within appears atrophied, and a good portion was torn away. The surgery to repair it left her left leg fractions shorter than her right, and when she’s on her feet for too long, she often displays a limp. When she has to make public appearances, or goes to the beach, she will hide it with a minor illusion.

TATTOOS. She has a turtle tattoo whose shell is filled in with the Hawai’ian archipelago and a hibiscus on her left back hip. She has a Tree of Life tattoo just below her neck and between her shoulder blades. She has a three-stud sub-dermal piercing along the inside of her right hip.

BUILD. Beth barely stands five feet tall, and tends to weigh between 90 and 96 pounds. If someone is being generous, she has been called petite, and slender. Beth sees herself as stunted and scrawny. She is perpetually underweight, despite her natural athleticism, and her curves are fairly modest, though she does have a rather lovely backside by western standards.

ALLERGIES. Bees, penicillin, latex, velvet.

USUAL HAIR STYLE. Beth hasn’t worn her hair naturally in years, but often wears it up in braids, buns, or pony-tails for work reasons.

USUAL CLOTHING. She spends a majority of her time in scrubs. She often wears business suits, or couture gowns for charitable efforts, but is most comfortable wearing as little as possible: bikinis/sleeveless blouses, long flowing skirts.

PSYCHOLOGY.

FEAR. The Dark. Heights. {{Being abandon/rejection/being alone}}

ASPIRATION. n/a

POSITIVE TRAITS. Beth is kind, caring, soft, compassionate, loving, understanding, charitable. She is highly intelligent, a talented witch, a staunch champion of others. She will go above and beyond for others, and will befriend literally anyone or anything.

NEGATIVE TRAITS. Shy, envious, deep-seated rage, self-sabotaging, self-critical to the point of hatred, exceptionally emotional. Easily feels slighted. Can be clingy, stubborn, or petulant.

VICE HABIT. Chronic insomniac, tends to drink wine to cover up feelings.

FAITH. Raised as a devout roman catholic. Has come to realise most gods are really just unfeeling bastards.

GHOSTS? She knows a few.

AFTERLIFE? Yes

REINCARNATION? Yes

ALIENS? She knows a few of these, too.

POLITICAL ALIGNMENT. Beth abhors human politics.

ECONOMIC PREFERENCE. She could live happily with absolutely nothing but the earth beneath her feet and all her worldly possessions in a sea-bag. But that’s easy to say as one of the richest people on the planet.

SOCIOPOLITICAL POSITION. She wishes people would quit ruining the world.

EDUCATION LEVEL. Master of Nursing Science. Medical Doctorate {Neurosurgery}. Highly talented Life/Blood witch, near professional surfer,

FAMILY.

FATHER. R. Admiral Brian C. Riley

MOTHER. Iwalani Kahanaui Stern {formerly Riley}

SIBLINGS. Andrew Riley- brother {deceased}, Jayden Morgan- hanai sister, William Manderly brother {unknown}

EXTENDED FAMILY. Drinks the Bitter Water - maternal grandfather, Anakone Kahananui - maternal uncle, Makaimakoa {Mike} Kahanui- maternal cousin, Tony DiNozzo- paternal cousin, Aislinn Riley- paternal aunt, Phil Coulson - hanai uncle, Loki Friggjarson, Hela Lokadottir- hanai daughter niece.

NAME MEANING. Elizabeth: God is my Oath, Irene: Peace, Alohaekaunei: Love alights here

HISTORICAL CONNECTION. n/a

FAVOURITES.

BOOKS. The Princess Bride but she reads everything

MOVIES. The Princess Bride and Tombstone

MUSIC. Everything but “Death metal”

DEITY. ...next question?

HOLIDAY. Mabon, the second harvest

MONTH. September

SEASON. Autumn/Winter

PLACE. Kalokoiki, on the North Shore, the Banzai pipeline.

WEATHER. rainy nights, dawn right before or after a storm when the waves are perfect.

SOUND. The sea, her brother’s singing

SCENT. lei flower {plumeria}, sandalwood, sea air

TASTE. li ming hui // honey // coffee // blood

FEEL. water // skin

ANIMAL. Cat, turtles, sharks

NUMBER. 3

COLOR. Purple

EXTRA.

TALENTS. Dancing, surfing, knitting, drawing

BAD AT. People. Hearing things in general. Cannot cook to save her life.

TURN ONS. Kindness. Intelligence. Someone who can challenge and engage her. Caresses along the small of her back, biting

TURN OFFS. Daddy-kinks, roses.

HOBBIES. Reading, surfing, hiking

TROPES. Manic Pixie Dream Witch // A Mistake is Born // Earth Mother // Granola Girl //

AESTHETICS. The sea, lava, blood, shy smiles, sharks.

FC INFO.

MAIN FC. Kristin Kreuk

ALT FC. This woman

OLDER FC. None

YOUNGER FC. Aubrey Anderson-Emmons

VOICE CLAIM. - Kristin Kreuk

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Doctors Without Borders/MSF calls US veto of Gaza ceasefire resolution “a vote against humanity”

"The US veto makes it complicit in the carnage in Gaza," said Avril Benoît, executive director of MSF-USA.

Today, December 8, the United Nations Security Council failed to adopt a resolution demanding a ceasefire in Gaza—blocked by a veto from the United States. The Security Council held an emergency meeting to discuss the humanitarian catastrophe in Gaza. This followed a letter from the UN Secretary-General invoking Article 99 to call on the Security Council to prevent further escalation and end this crisis. In addition to demanding an immediate humanitarian ceasefire, the draft resolution tabled by the United Arab Emirates reiterated the Security Council's demand on all parties to comply with their obligations under international law, notably with regard to the protection of civilians in Palestine and Israel.

Avril Benoît, executive director of Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) USA gave the following statement:

“As bombs continue to rain down on Palestinian civilians and cause widespread destruction, the US has once again used its power to block an attempt by the UN Security Council to demand a ceasefire in Gaza. By vetoing this resolution, the US stands alone in casting its vote against humanity.

The US veto stands in sharp contrast to the values it professes to uphold. By continuing to provide diplomatic cover for the ongoing atrocities in Gaza, the US is signaling that international humanitarian law can be applied selectively—and that the lives of some people matter less than the lives of others.

Israel has continued to indiscriminately attack civilians and civilian structures, impose a siege that amounts to collective punishment for the entire population of Gaza, force mass displacement, and deny access to vital medical care and humanitarian assistance. The US continues to provide political and financial support to Israel as it prosecutes its military operations regardless of the terrible toll on civilians. For humanitarians to be able to respond to the overwhelming needs, we need a ceasefire now.

The US veto makes it complicit in the carnage in Gaza.”

#where is the humanity?#doctors without borders#the US has the blood of millions of innocents on its hands#complicit in genocide#shame on the us#genocide#israel is an apartheid state#apartheid#ethnic cleansing#collective punishment#nakba 2023#israeli war crimes#netanyahu is a war criminal#israel is a terrorist state#israel is not the victim#anti zionism isnt anti semitism#stop weaponizing words to prevent debate

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

La playlist de l'émission de ce jeudi matin sur Radio Campus Bruxelles entre 6h30 et 9h : David Sylvian "Blemish" (Blemish/Samadhisound Label/2003) Gastr del Sol "The Sea Incertain" (Upgrade & Afterlife/Drag City Records/1996) Lambchop "Daisy" (The Bible/City Slang/2022) Antony (ANOHNI) "Hole in my Soul" (Not Alone - Médecins Sans Frontières - Doctors Without Borders/Durtro/2006) Colette Magny "Bura bura" (Colette Magny/Le Chant du Monde/1967) Oiseaux-Tempête "A Man Alone in a One Man Poem" (What on Earth (Que Diable)/Sub Rosa/2022) Lord Buckley "The Train" (A Most Immaculately Hip Aristocrat/Straight/1969) Astéréotypie "Aucun mec ne ressemble à Brad Pitt dans la Drôme" (Aucun mec ne ressemble à Brad Pitt dans la Drôme/La Belle Brute/2022) LEM "Sous les cyprès" (Bientôt Le Cosmos/Heroika/2003-2022) Carla dal Forno "Caution" (Come Around/Kallista Records/2022) The Legendary Stardust Cowboy "Paralyzed" (7"/Munster Records/1968-2016) Beat Happening "Angel Gone" (Music to Climb The Apple Tree By/Krecs/2000-2003) Françoiz Breut, Mathieu Pierloot, Claire Vailler, Mocke "Les forges" (Grand déménagement/Le label dans la forêt/2022) K'dlokk "Nagyon Szeretrek Mindenkinek" (Alien Parade Japan/Alien Transistor/2022) Malcolm Middleton & Alan Bissett "The Rebel on his Own Tonight" (Ballads of the Book/Chemikal Underground/2007) Yellow Magic Orchestra "Firecracker" (12"/A&M Records/1979) Rachid Taha "Barra Barra" (Rock'n'Raï/Barclay/2000-2020) Susanna and the Magical Orchestra "Enjoy the Silence" (Melody Mountain/rune grammofon/2006) Millie Jackson "If Loving You Is Wrong I Don't Want To Be Right / The Rap" (Caught Up/Southbound/1974-2018) Charles Stepney "Look B4U Leap" (Step On Step/International Anthem/2022) The Honeymoon Killers "A Deep Space Romance (Ariane)" (Subtitled Remix/Crammed Discs/1983) https://www.instagram.com/p/ClDynymtiP5/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

1 note

·

View note

Photo

With world hunger increasing by the day, a situation that is being aggravated by the war in Ukraine, a watch from NOMOS Glashütte is here to lend a helping hand by making a generous contribution—while inspiring others to do the same: Nomos Tangente 38 – 50 Ans de Médecins sans Frontières. Adversity is growing. Already 800 million people worldwide are starving. A combination of various crises have exacerbated an already difficult situation in many regions of the world: local conflicts, the pandemic, droughts and crop failures, the death of livestock, and now the war in Ukraine. The latter is also causing food prices for countries in the global south to soar to almost incalculable levels. “In one week alone, we admitted almost 1,000 children to our outpatient therapeutic feeding program. Thirty per cent of them were suffering from severe acute malnutrition,” reports Bakri Abubakr, Doctors Without Borders’ program manager in Somalia. https://www.instagram.com/p/Cg9J4fSr-FT/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Photo

Cakeisnotpie

See Cakeisnotpie’s existing works here.

Preferred contact methods:

Tumblr: cakeisnotpie

Preferred organizations:

- First Book

- Global Fund for Women

- Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders)

- Rainbow Railroad

- The Trevor Project

(See the list of approved organizations here)

Will create works that contain:

Pretty much open to anything. I tend to write mostly AUs and my fics usually have HEA.

Will not create works that contain:

a/b/o, mpreg, non-con, really dark fic

-- Fic or Other Writing --

Auction ID: 1190

Will create works for the following relationships:

Clint Barton/Phil Coulson - MCU

Steve Rogers/Tony Stark - MCU

Bucky Barnes/Clint Barton/Natasha Romanov - MCU

Bucky Barnes/Steve Rogers - MCU

Bucky Barnes/Clint Barton/Sam Wilson - MCU

Clint Barton/Steve Rogers - MCU

Clint Barton/Tony Stark - MCU

Bruce Banner/Clint Barton - MCU

Bucky Barnes/Sam Wilson - MCU

Work Description:

A one-shot story with the chosen pairing. Winner may suggest a topic and prompt; I will take that and craft a one chapter fic. Most of my one shots run around 4500 to 5000 words. If the winner wants, I'm open to continuing a current series or creating a stand-alone.

Ratings: Gen, Teen, Mature, Explicit

CLICK HERE TO BID ON THIS WORK

-- Fic or Other Writing --

Auction ID: 2076

Will create works for the following relationships:

Bruce Banner/Clint Barton - MCU

Bucky Barnes/Clint Barton - MCU

Bucky Barnes/Clint Barton/Natasha Romanov - MCU

Bucky Barnes/Sam Wilson - MCU

Bucky Barnes/Steve Rogers - MCU

Bucky Barnes/Clint Barton/Steve Rogers - MCU

Steve Rogers/Tony Stark - MCU

Clint Barton/Phil Coulson - MCU

Clint Barton/Steve Rogers - MCU

Work Description:

This is a medium length multi-chapter fic (5-7 chapters) written for the winner's prompt and suggestions. I am open to Alternative Universes as well as other kinds of plotted fics. Winners may elect the story to be part of an on-going series.

Ratings: Gen, Teen, Mature, Explicit

CLICK HERE TO BID ON THIS WORK

-- Fic or Other Writing --

Auction ID: 3026

Will create works for the following relationships:

Clint Barton/Phil Coulson - MCU

Bruce Banner/Clint Barton - MCU

Clint Barton/Tony Stark - MCU

Bucky Barnes/Clint Barton - MCU

Bucky Barnes/Clint Barton/Natasha Romanov - MCU

Bucky Barnes/Clint Barton/Steve Rogers - MCU

Clint Barton/Steve Rogers - MCU

Steve Rogers/Tony Stark - MCU

Bucky Barnes/Sam Wilson - MCU

Work Description:

This is a longer multi-chapter fic, an AU of the winner's choosing. My long fics run anywhere from 16-20 chapters and can take anywhere from 4-6 months to complete. Winner will provide a prompt and I will build the world and create the story. Story may include a primary and up to 2 secondary pairings.

Ratings: Gen, Teen, Mature, Explicit

CLICK HERE TO BID ON THIS WORK

The auction runs from October 18 (12 AM ET) to October 24 (11:59:59 PM ET). Visit marveltrumpshate.com during Auction Week to view all of our auctions and to place your bids!

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Support a Record Breaking Charity Event!

Hey guys! I’m raising money this year for a huge charity event at my high school. It’s Scona’s Annual Bikeathon! Each team bikes for 24 hours in support of a different charity every year. This year we’ve chosen Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF).

“[In 2015], the event was declared Canada’s largest school service project, raising $352,000 for Edmonton’s Bissell Centre.” (CBC)

“In 2017 alone, MSF supporters helped us treat 10,648,300 outpatients, assist 23,900 migrants and refugees at sea, and vaccinate 2,095,000 people against a measles outbreak. Because of your support, we treated 2,520,600 cases of malaria in 2017, and provided 306,300 mental health consultations. Working in nearly 70 countries around the world, people like you are helping us provide emergency medical care to families who have lost so much.” (MSF Official Website)

Last year we raised over $500,000 for Earth Group & The United Nations World Food Program.

https://globalnews.ca/news/4089479/strathcona-high-school-feed-the-hungry/

Be apart of the change and donate by clicking the link below! Anything, even 1 cent helps. Honestly, it truly does. This cause is so close to my heart and hopefully you guys feel that too. Thank you for all your support and I’m sure I’ll thank you all again in beginning of March 2019 when we do the Bikeathon and I’ll let you know how much we raised! See you guys all soon 😋

http://www.asonewhoserves.ca/bikeatons

#charity#edmonton#yeg#doctors without borders#msf#bikeathon#strathcona#important#relevent#current events#original content#nonprofit#not for profit#news#activism#activist#canada#high school#highschool

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exhibition Review: Robert Longo The Destroyer Cycle at Metro Pictures

By: Madeline Leddy

When Musée’s Steve Miller interviewed multimedia artist Robert Longo back in March of 2016, Longo talked a lot about death. “We are trying to deny death, to look it in the face and say I’m not scared,” he said, speaking on behalf of artists like Hanne Darboven, but also discussing influence from thinkers like Walter Benjamin and Roland Barthes. It is clear, from Longo’s latest work—particularly the massive charcoal pieces he has finished since giving that interview—that his later work has much in common with the poststructuralist tendencies of Benjamin and Barthes, (both of whom wrote a fair amount on photography as a medium and practice) than it does with any particular artistic movement to which critics have linked Longo, from Abstract Expressionism to Pop Art.

Viewing Longo’s work shows the extent to which curating it, let alone creating it, must have been an intellectual exercise. The photos of which Longo works all contain messages of some sort—some overtly political, some more ambiguous. The process of translating the (usually color) images to black and white charcoal entails important choices about what aspects of the image will be emphasized in the new form; like a linguistic translator, Longo bears the burden of deciding what nuances he will maintain, how he will maintain them, and what facets of the image he will choose to emphasize. In his case, nuances of color rather than words. But colors, in an image, function in an analogous way to words in prose.

The tactile nature of charcoal allows Longo to add a dimension to his works, which are photorealist from afar, and more impressionistic up close. At the details where he wants to add emphasis, Longo piles on the black powder; this creates slightly three-dimensional contours that, paradoxically, make the work of art itself seem more real, but its content more abstract.

So how is it that Longo’s translation of a photograph as powerful as the newspaper shot of five St. Louis Rams players in “hands up, don’t shoot” formation on the field, or of a precarious refugee-filled raft tossing in a seemingly endless gray sea, can be even more arresting than the original image itself ? The philosophical roots of Longo’s process give the charcoal productions a story, even, in a way, a raison d’être, but there is something even more sobering in every experience of looking at these huge, monochrome projections of images that should look familiar to us but, in this new form, do not.

The answer to this question may be best attempted from the starting point of one of the seemingly very apolitical works of the show, Longo’s study of an x-ray of Titian’s Venus with a Mirror (1555). His fascination with x-rays of famous works of art, as he noted in an interview with Kaleidoscope, stems from his engagement with Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Production, and embodies his consistent insertion of himself as an artist into the realm of critical theory. By blowing up a copy of Titian’s painting and revealing the layers of lacquered-over sketches behind the visible picture, Longo provides himself with a ghostly template for his charcoal translation—and, unsurprisingly, the rendering of the x-ray in black and white only augments this quality of ghostliness. Two hidden figures, one apparently male, the other female, both adults, emerge in the shadows behind Titian’s finished Venus, and Longo appears to have chosen to emphasize their presence as voyeurs, darkening and thickening the contours that define their faces and groping hands, while fading out the now-vulnerable Venus. Venus seems to have lost agency, and all this at the fault of a technological maneuver that Titian, himself, could not likely have dreamed of—and that Longo, in an exercise of his own agency, has used to reconfigure the artist’s intentions.

The exhibit’s pièces de résistance, however, were not necessarily those that engaged with archaic art. These ones—that had a group of high school students on a gallery visit crowding for a better view—were given ample space to shine: the three-panel refugee boat downstairs, and a pair of dialoguing works upstairs: one of a darkened American flag, the other, positioned on the opposite wall, of a cracked iPhone screen taken in close-up.

The refugee boat photo, pulled from a Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders/MSF) flyer, is as evocative in its subject matter as in its portrayal: here, Longo’s charcoal shadows the eyes of the raft riders’ faces, some of which are visible to us as they look over their shoulders. The eyes become black sockets, an effect perhaps best captured in Longo’s smoky medium. His choice to use a piece of photojournalism as his base for this work, as well, recalls his ongoing engagement with Benjaminian thought: while journalism is, in an ideal world, supposed to be an objective practice—and on-the-fly, unstaged photojournalism made possible by increasingly agile technology. It is still a means of capturing a moment that will have an effect on the world, and cannot be totally free of the capturer’s (journalist’s or photojournalist’s) subjectivity.

The upstairs portion of the installation, which consists of Untitled (Nov. 8, 2016) (the American flag work), Untitled (Shattered iPhone Screen), and Study of Lights Out, which depicts an eerie backlit shadow of the Statue of Liberty, is a small room that is almost dwarfed by the wall-length works; and it is in this intimate space that the viewer is confronted with, perhaps, the most striking, even though ambiguous, symbolism of Longo’s message. We are confronted with America, literally in black and white, and she is—if this part of the installation is conceived as a small whole, a coherent sub-message—on the verge of cracking. Standing in front of the glass-protected Untitled (Shattered iPhone Screen), you can see the reflection of the American flag from its facing wall—and it looks broken. Lady Liberty, a few meters to the side, offers more of an omen than a beam of hope. In fact, she seems contemplative—much like the viewer, lost in the infinite reflection between cracked iPhone screen and American flag—and much like Longo himself, we can imagine. These are images that force us to think about what living in the twenty first century means for art, and consider the damage society has inflicted upon itself. Art can make us contemplate these things, but cannot fix them independently.

#review#robert longo#metro pictures#pictures#metro#photography#destroyer cycle#destroy#cycle#death#american flag#america#liberty#lady liberty#musee#museemagazine#muséemagazine#musée#magazine

0 notes

Link

Behind barbed wire, within view of Texas, 2,200 migrants live in a netherworld between U.S. and Mexican responsibility. No one's in charge and amateurs are rushing in to help. Desperate conditions and an abiding despair are forcing awful choices. Some people think that's the point. Leaked Letter Shows Where Military Will Reinforce Trump’s Border WallMATAMOROS, Mexico—In the year since the Trump Administration instituted the Migrant Protection Protocols, known as the Remain in Mexico policy, a sprawling encampment has grown in Matamoros, just a shout across the Rio Grande from Brownsville, Texas. The people here are under the jurisdiction of the United States, although they sleep at the very edge of a country neither their own nor the one they seek. The camp exists between Mexican and U.S. authority and outside international law. It's not an official refugee camp, though it certainly looks like one. Dozens of tents are pitched in rows on the tennis courts and soccer pitch of a city park and covered in black garbage bags to keep out the rain. Men lug plastic hardware-store buckets to collect water. They have built tables out of logs and the flat boards of shipping pallets lashed together with rope. Women pat masa into tortillas and cook on grills over wood fires (park trees chopped down for the purpose). The camp is a waiting room for the U.S. immigration courts, which operate out of a warren of white tents on the Texas side of the river. But the wait is long. Many have hearings set for March or April, five and six months after they first presented their asylum claims. The camp teems with children, young, skinny Central Americans with indigenous faces. On Feb. 1, UNICEF issued a statement saying the agency had begun developing places for the children to play, some basic health screening and organization of water and sanitation services. But these are minimal and belated. Migrants seeking asylum in the United States have been sleeping in Matamoros since July. In the absence of official international system management, social service workers, attorneys, activists, crisis junkies, Silicon Valley millionaires and organized and freelance do-gooders have filled the vacuum. Some have experience responding to crisis. Some have no idea what they are doing. No one is in charge. An Italian tourist is running a photography class for kids. A self-described redneck anarchist is managing logistics and operations: what to do with 100 camp stoves donated by a philanthropist, where to locate the garbage barrels a charity is buying. An evangelical pastor associated with Franklin Graham who runs a hip-hop church in Matamoros is helping organize a council of camp residents to make joint decisions. A clutch of acupuncturists is extolling the trauma-relieving properties of their art.There is no vetting. The volunteers who walk into the camp with some idea of doing good receive no screening or training on the risks that the migrants face. Some take pictures and post to social media long accounts filled with details of migrants' asylum claims. A knot of GoFundMe and Kickstarter pages without accounting safeguards collect donations for a mushrooming variety of initiatives, some well-grounded, some not. Not that there haven’t been efforts to organize and control the chaos. They just haven’t been effective. Since December, Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley, a U.S. group called Angry Tias and Abuela, and others have met weekly with the Mexican immigration authorities. Bria Schurke, a physician's assistant from northern Minnesota, is on her fourth stint in a makeshift health clinic run by Global Response Management, a tiny nonprofit that also has clinics in Yemen, Syria, and Iraq. She worked in refugee camps in East Africa, and is alarmed by the rookies, the lack of ethical protocols governing humanitarian relief in Matamoros. "Because it's accessible a lot of people are showing up, well intentioned or not," Schurke said. Most of the patients Schurke sees in the clinic have respiratory infections or intestinal illnesses, scabies or lice. There is malnutrition, but the most severe malady is fear. The camp inhabitants are popular targets for the drug cartels and human trafficking operations that hold power in Matamoros. Migrants are subject to kidnapping, torture, and rape, according to “A Year of Horrors,” a new report by Human Rights First. It tallied 201 cases of kidnapping and attempted kidnapping of children under the Migrant Protection Protocols.A Feb. 12 report called "No Way Out," from Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières, is equally dire. In October 2019, the report notes, of the patients MSF cared for in one border town, 75 percent had been kidnapped recently.An MSF psychologist and two other workers have been serving migrants in the city of Matamoros since September. At the beginning of February they began working inside the migrant camp with a doctor two days a week. In addition to infections and injuries from exposure, hunger and walking hundreds of miles, MSF staff see truama from abuse suffered along the migrant root and also inside U.S. detention centers.The report called the levels of violence that migrants are fleeing in Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras “comparable to that in war zones where MSF has been working for decades” and “a major factor fueling migration north to Mexico and the U.S.”But admittance into the United States may never come. Returning home is not an option. Conditions are desperate enough that some parents have sent their children across the bridge into the U.S. alone, deciding they are better off in detention centers than the precarity of camp.These are choices parents shouldn't be compelled to contemplate, said Jennifer Nagda, policy director for the Young Center for Immigrant Children's Rights, who visited the camp in January. “There shouldn't be a camp,” Nadga said, punching each word. “This is a completely new and unprecedented effort—in contravention of international treaties and obligations. It's an explicit effort to make it impossible for people to exercise their legal rights.”On the Brownsville side of the river, a clutch of protestors sits in a small park in vigil. They will stay, they say, until their country recants its crimes. They believe the camp and the desperation it breeds are intentional designs of a government intent on dehumanizing a hated population.Drawing comparisons to the treatment of Jews in the years before the Holocaust, Joshua Rubin, a retired computer programmer from Brooklyn, who is Jewish, says he feels compelled to be a witness, to not look away when his country is doing something wrong. He organized the protest called Vigil at the Border. He and the others will remain, he said, holding their "Let Them In" and "History is Watching" signs until the U.S. reverses the Remain in Mexico policy. "I don't have a lot of hope that that will happen, but I don’t have much choice," Rubin said. "You can't close your eyes and make it go away."Back in Matamoros on a Friday afternoon in late January a hundred people walked into a tent—large and white like something for a wedding except this was about separation not union—sat themselves in rows and listened as two attorneys from the Young Center gave a briefing:Here is the process that will confront your children if you send them over the bridge by themselves. They will be collected. They will be sent to a prison-like detention center. They will be assigned a case number. They will get a calendar date. They will be under the authority of federal agents. They may spend months or years in this facility. They may be sent to foster care. The people with whom they live may or may not speak Spanish. They may be able to connect to your brother, your aunt, your cousin in New York, in Michigan, in California. They may not. You might never see them again.The Hondurans, Salvadorans, Guatemalans, Nicaraguans listened in weary attention. In the front row, a toddler breast-fed luxuriantly, in the way of toddlers, full, entitled, the fingers of his hand splayed proprietarily on his mother’s side. She wiped her eyes repeatedly and blinked hard.Leaning forward, heads inclined and faces stoic, the migrants listened to the lawyers' words. They were not hopeful.Gladis Molina Alt, director of the Young Center's Child Advocacy Program, was herself once a migrant. Her father fled Morazán, El Salvador in the early years of that country’s war, swam the river and got himself to Los Angeles. He sent for her and her brothers and mother later. She arrived in the U.S. at age 10. Became a citizen at 27. Went to law school and now, pulled by history, works as a legal advocate for other migrant children.Today is different though. Ordinarily she works the hard cases of children in detention. Today she is at the other end of the story, speaking to parents in the camp who may have received some very bad advice.An American woman visiting the camp has told families she can get their children into the United States, that within a week they will be with those family members waiting in Maryland or Iowa or Oregon.The woman has no way of ensuring this. No expertise or authority. But families have trusted a heart-sick gringa. They sent their children to stand on a small bridge across the Rio Grande and throw themselves on the anemic mercy of Customs and Border Patrol. It is difficult to learn where those children are today. The federal detention, supervision and child management system is vast and anything but transparent. Still, after the briefing a quiet line forms, then encircles the attorneys, women and men wanting more information.The breast-feeding mother is among them. The next day, climbing out of the tent she shares with her husband and children, holding the happy toddler on her hip while her older child plays soccer in the dust, she explains. The little one is too small to send, but she is worried for the fate of her nine-year-old son in the camp. The kind of people they fled El Salvador to avoid are active here. She knows they'll prey on the boy.It feels like psychological war being kept here, she says: the waiting, the uncertainty. Yet if they return to El Salvador she is sure they will be killed. "I have to think of sending him," she says, crying now. "There is no life here." She and her family are among tens of thousands of Central Americans who’ve fled north in the past decade: 35,000 people from Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras sought asylum at the U.S. border in 2017, the last year for which Department of Homeland Security data was readily available. An additional 75,000 people from those three nations sought asylum when faced with deportation the same year. Asylum claims from the northern triangle of Central America jumped 800 percent between 2012 and 2017 according to DHS’ Annual Flow Report on Refugees and Asylees from March 2019.Holocaust Survivor: Yes, the Border Detention Centers Are Like Concentration CampsThe migrants are driven from nations deformed by brutality, where the social and psychological wounds of wars committed a generation ago festered into drug, gang and government violence today that leaves few families safe. Last week Human Rights Watch released a report documenting cases of 138 Salvadorans who were killed after being deported back into their country.The parents who circled the lawyers after the briefing in Matamoros had similar fears and questions: How long, really, before they get out of detention? My children are gone, how will I find them? What if their claim of asylum has already been rejected? Does that count against them? How will it affect my own case? Is there a way to do something to make it more possible that I might see them again? There is no life here. I cannot take them back to Honduras/El Salvador/Guatemala. We will be killed."It's Sophie's Choice, but you don't get to keep one of them," another lawyer with long experience and red eyes said after she stepped away from a conference you might call a sidewalk conference, but for the fact there was no sidewalk.Only cracked, very dry ground.Read more at The Daily Beast.Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.

from Yahoo News - Latest News & Headlines https://ift.tt/39GPR3H

0 notes

Link

Behind barbed wire, within view of Texas, 2,200 migrants live in a netherworld between U.S. and Mexican responsibility. No one's in charge and amateurs are rushing in to help. Desperate conditions and an abiding despair are forcing awful choices. Some people think that's the point. Leaked Letter Shows Where Military Will Reinforce Trump’s Border WallMATAMOROS, Mexico—In the year since the Trump Administration instituted the Migrant Protection Protocols, known as the Remain in Mexico policy, a sprawling encampment has grown in Matamoros, just a shout across the Rio Grande from Brownsville, Texas. The people here are under the jurisdiction of the United States, although they sleep at the very edge of a country neither their own nor the one they seek. The camp exists between Mexican and U.S. authority and outside international law. It's not an official refugee camp, though it certainly looks like one. Dozens of tents are pitched in rows on the tennis courts and soccer pitch of a city park and covered in black garbage bags to keep out the rain. Men lug plastic hardware-store buckets to collect water. They have built tables out of logs and the flat boards of shipping pallets lashed together with rope. Women pat masa into tortillas and cook on grills over wood fires (park trees chopped down for the purpose). The camp is a waiting room for the U.S. immigration courts, which operate out of a warren of white tents on the Texas side of the river. But the wait is long. Many have hearings set for March or April, five and six months after they first presented their asylum claims. The camp teems with children, young, skinny Central Americans with indigenous faces. On Feb. 1, UNICEF issued a statement saying the agency had begun developing places for the children to play, some basic health screening and organization of water and sanitation services. But these are minimal and belated. Migrants seeking asylum in the United States have been sleeping in Matamoros since July. In the absence of official international system management, social service workers, attorneys, activists, crisis junkies, Silicon Valley millionaires and organized and freelance do-gooders have filled the vacuum. Some have experience responding to crisis. Some have no idea what they are doing. No one is in charge. An Italian tourist is running a photography class for kids. A self-described redneck anarchist is managing logistics and operations: what to do with 100 camp stoves donated by a philanthropist, where to locate the garbage barrels a charity is buying. An evangelical pastor associated with Franklin Graham who runs a hip-hop church in Matamoros is helping organize a council of camp residents to make joint decisions. A clutch of acupuncturists is extolling the trauma-relieving properties of their art.There is no vetting. The volunteers who walk into the camp with some idea of doing good receive no screening or training on the risks that the migrants face. Some take pictures and post to social media long accounts filled with details of migrants' asylum claims. A knot of GoFundMe and Kickstarter pages without accounting safeguards collect donations for a mushrooming variety of initiatives, some well-grounded, some not. Not that there haven’t been efforts to organize and control the chaos. They just haven’t been effective. Since December, Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley, a U.S. group called Angry Tias and Abuela, and others have met weekly with the Mexican immigration authorities. Bria Schurke, a physician's assistant from northern Minnesota, is on her fourth stint in a makeshift health clinic run by Global Response Management, a tiny nonprofit that also has clinics in Yemen, Syria, and Iraq. She worked in refugee camps in East Africa, and is alarmed by the rookies, the lack of ethical protocols governing humanitarian relief in Matamoros. "Because it's accessible a lot of people are showing up, well intentioned or not," Schurke said. Most of the patients Schurke sees in the clinic have respiratory infections or intestinal illnesses, scabies or lice. There is malnutrition, but the most severe malady is fear. The camp inhabitants are popular targets for the drug cartels and human trafficking operations that hold power in Matamoros. Migrants are subject to kidnapping, torture, and rape, according to “A Year of Horrors,” a new report by Human Rights First. It tallied 201 cases of kidnapping and attempted kidnapping of children under the Migrant Protection Protocols.A Feb. 12 report called "No Way Out," from Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières, is equally dire. In October 2019, the report notes, of the patients MSF cared for in one border town, 75 percent had been kidnapped recently.An MSF psychologist and two other workers have been serving migrants in the city of Matamoros since September. At the beginning of February they began working inside the migrant camp with a doctor two days a week. In addition to infections and injuries from exposure, hunger and walking hundreds of miles, MSF staff see truama from abuse suffered along the migrant root and also inside U.S. detention centers.The report called the levels of violence that migrants are fleeing in Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras “comparable to that in war zones where MSF has been working for decades” and “a major factor fueling migration north to Mexico and the U.S.”But admittance into the United States may never come. Returning home is not an option. Conditions are desperate enough that some parents have sent their children across the bridge into the U.S. alone, deciding they are better off in detention centers than the precarity of camp.These are choices parents shouldn't be compelled to contemplate, said Jennifer Nagda, policy director for the Young Center for Immigrant Children's Rights, who visited the camp in January. “There shouldn't be a camp,” Nadga said, punching each word. “This is a completely new and unprecedented effort—in contravention of international treaties and obligations. It's an explicit effort to make it impossible for people to exercise their legal rights.”On the Brownsville side of the river, a clutch of protestors sits in a small park in vigil. They will stay, they say, until their country recants its crimes. They believe the camp and the desperation it breeds are intentional designs of a government intent on dehumanizing a hated population.Drawing comparisons to the treatment of Jews in the years before the Holocaust, Joshua Rubin, a retired computer programmer from Brooklyn, who is Jewish, says he feels compelled to be a witness, to not look away when his country is doing something wrong. He organized the protest called Vigil at the Border. He and the others will remain, he said, holding their "Let Them In" and "History is Watching" signs until the U.S. reverses the Remain in Mexico policy. "I don't have a lot of hope that that will happen, but I don’t have much choice," Rubin said. "You can't close your eyes and make it go away."Back in Matamoros on a Friday afternoon in late January a hundred people walked into a tent—large and white like something for a wedding except this was about separation not union—sat themselves in rows and listened as two attorneys from the Young Center gave a briefing:Here is the process that will confront your children if you send them over the bridge by themselves. They will be collected. They will be sent to a prison-like detention center. They will be assigned a case number. They will get a calendar date. They will be under the authority of federal agents. They may spend months or years in this facility. They may be sent to foster care. The people with whom they live may or may not speak Spanish. They may be able to connect to your brother, your aunt, your cousin in New York, in Michigan, in California. They may not. You might never see them again.The Hondurans, Salvadorans, Guatemalans, Nicaraguans listened in weary attention. In the front row, a toddler breast-fed luxuriantly, in the way of toddlers, full, entitled, the fingers of his hand splayed proprietarily on his mother’s side. She wiped her eyes repeatedly and blinked hard.Leaning forward, heads inclined and faces stoic, the migrants listened to the lawyers' words. They were not hopeful.Gladis Molina Alt, director of the Young Center's Child Advocacy Program, was herself once a migrant. Her father fled Morazán, El Salvador in the early years of that country’s war, swam the river and got himself to Los Angeles. He sent for her and her brothers and mother later. She arrived in the U.S. at age 10. Became a citizen at 27. Went to law school and now, pulled by history, works as a legal advocate for other migrant children.Today is different though. Ordinarily she works the hard cases of children in detention. Today she is at the other end of the story, speaking to parents in the camp who may have received some very bad advice.An American woman visiting the camp has told families she can get their children into the United States, that within a week they will be with those family members waiting in Maryland or Iowa or Oregon.The woman has no way of ensuring this. No expertise or authority. But families have trusted a heart-sick gringa. They sent their children to stand on a small bridge across the Rio Grande and throw themselves on the anemic mercy of Customs and Border Patrol. It is difficult to learn where those children are today. The federal detention, supervision and child management system is vast and anything but transparent. Still, after the briefing a quiet line forms, then encircles the attorneys, women and men wanting more information.The breast-feeding mother is among them. The next day, climbing out of the tent she shares with her husband and children, holding the happy toddler on her hip while her older child plays soccer in the dust, she explains. The little one is too small to send, but she is worried for the fate of her nine-year-old son in the camp. The kind of people they fled El Salvador to avoid are active here. She knows they'll prey on the boy.It feels like psychological war being kept here, she says: the waiting, the uncertainty. Yet if they return to El Salvador she is sure they will be killed. "I have to think of sending him," she says, crying now. "There is no life here." She and her family are among tens of thousands of Central Americans who’ve fled north in the past decade: 35,000 people from Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras sought asylum at the U.S. border in 2017, the last year for which Department of Homeland Security data was readily available. An additional 75,000 people from those three nations sought asylum when faced with deportation the same year. Asylum claims from the northern triangle of Central America jumped 800 percent between 2012 and 2017 according to DHS’ Annual Flow Report on Refugees and Asylees from March 2019.Holocaust Survivor: Yes, the Border Detention Centers Are Like Concentration CampsThe migrants are driven from nations deformed by brutality, where the social and psychological wounds of wars committed a generation ago festered into drug, gang and government violence today that leaves few families safe. Last week Human Rights Watch released a report documenting cases of 138 Salvadorans who were killed after being deported back into their country.The parents who circled the lawyers after the briefing in Matamoros had similar fears and questions: How long, really, before they get out of detention? My children are gone, how will I find them? What if their claim of asylum has already been rejected? Does that count against them? How will it affect my own case? Is there a way to do something to make it more possible that I might see them again? There is no life here. I cannot take them back to Honduras/El Salvador/Guatemala. We will be killed."It's Sophie's Choice, but you don't get to keep one of them," another lawyer with long experience and red eyes said after she stepped away from a conference you might call a sidewalk conference, but for the fact there was no sidewalk.Only cracked, very dry ground.Read more at The Daily Beast.Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.

from Yahoo News - Latest News & Headlines https://ift.tt/39GPR3H

0 notes

Video

youtube

The Hafler Trio - The Work of Washing

from:

VA - Not Alone - Médecins Sans Frontières - Doctors Without Borders (Durtro, Jnana, 2006)

#2000s#The Hafler Trio#andrew mckenzie#electronic#experimental#minimal#ambient#industrial#Durtro#Jnana#2006

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

Behind barbed wire, within view of Texas, 2,200 migrants live in a netherworld between U.S. and Mexican responsibility. No one's in charge and amateurs are rushing in to help. Desperate conditions and an abiding despair are forcing awful choices. Some people think that's the point. Leaked Letter Shows Where Military Will Reinforce Trump’s Border WallMATAMOROS, Mexico—In the year since the Trump Administration instituted the Migrant Protection Protocols, known as the Remain in Mexico policy, a sprawling encampment has grown in Matamoros, just a shout across the Rio Grande from Brownsville, Texas. The people here are under the jurisdiction of the United States, although they sleep at the very edge of a country neither their own nor the one they seek. The camp exists between Mexican and U.S. authority and outside international law. It's not an official refugee camp, though it certainly looks like one. Dozens of tents are pitched in rows on the tennis courts and soccer pitch of a city park and covered in black garbage bags to keep out the rain. Men lug plastic hardware-store buckets to collect water. They have built tables out of logs and the flat boards of shipping pallets lashed together with rope. Women pat masa into tortillas and cook on grills over wood fires (park trees chopped down for the purpose). The camp is a waiting room for the U.S. immigration courts, which operate out of a warren of white tents on the Texas side of the river. But the wait is long. Many have hearings set for March or April, five and six months after they first presented their asylum claims. The camp teems with children, young, skinny Central Americans with indigenous faces. On Feb. 1, UNICEF issued a statement saying the agency had begun developing places for the children to play, some basic health screening and organization of water and sanitation services. But these are minimal and belated. Migrants seeking asylum in the United States have been sleeping in Matamoros since July. In the absence of official international system management, social service workers, attorneys, activists, crisis junkies, Silicon Valley millionaires and organized and freelance do-gooders have filled the vacuum. Some have experience responding to crisis. Some have no idea what they are doing. No one is in charge. An Italian tourist is running a photography class for kids. A self-described redneck anarchist is managing logistics and operations: what to do with 100 camp stoves donated by a philanthropist, where to locate the garbage barrels a charity is buying. An evangelical pastor associated with Franklin Graham who runs a hip-hop church in Matamoros is helping organize a council of camp residents to make joint decisions. A clutch of acupuncturists is extolling the trauma-relieving properties of their art.There is no vetting. The volunteers who walk into the camp with some idea of doing good receive no screening or training on the risks that the migrants face. Some take pictures and post to social media long accounts filled with details of migrants' asylum claims. A knot of GoFundMe and Kickstarter pages without accounting safeguards collect donations for a mushrooming variety of initiatives, some well-grounded, some not. Not that there haven’t been efforts to organize and control the chaos. They just haven’t been effective. Since December, Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley, a U.S. group called Angry Tias and Abuela, and others have met weekly with the Mexican immigration authorities. Bria Schurke, a physician's assistant from northern Minnesota, is on her fourth stint in a makeshift health clinic run by Global Response Management, a tiny nonprofit that also has clinics in Yemen, Syria, and Iraq. She worked in refugee camps in East Africa, and is alarmed by the rookies, the lack of ethical protocols governing humanitarian relief in Matamoros. "Because it's accessible a lot of people are showing up, well intentioned or not," Schurke said. Most of the patients Schurke sees in the clinic have respiratory infections or intestinal illnesses, scabies or lice. There is malnutrition, but the most severe malady is fear. The camp inhabitants are popular targets for the drug cartels and human trafficking operations that hold power in Matamoros. Migrants are subject to kidnapping, torture, and rape, according to “A Year of Horrors,” a new report by Human Rights First. It tallied 201 cases of kidnapping and attempted kidnapping of children under the Migrant Protection Protocols.A Feb. 12 report called "No Way Out," from Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières, is equally dire. In October 2019, the report notes, of the patients MSF cared for in one border town, 75 percent had been kidnapped recently.An MSF psychologist and two other workers have been serving migrants in the city of Matamoros since September. At the beginning of February they began working inside the migrant camp with a doctor two days a week. In addition to infections and injuries from exposure, hunger and walking hundreds of miles, MSF staff see truama from abuse suffered along the migrant root and also inside U.S. detention centers.The report called the levels of violence that migrants are fleeing in Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras “comparable to that in war zones where MSF has been working for decades” and “a major factor fueling migration north to Mexico and the U.S.”But admittance into the United States may never come. Returning home is not an option. Conditions are desperate enough that some parents have sent their children across the bridge into the U.S. alone, deciding they are better off in detention centers than the precarity of camp.These are choices parents shouldn't be compelled to contemplate, said Jennifer Nagda, policy director for the Young Center for Immigrant Children's Rights, who visited the camp in January. “There shouldn't be a camp,” Nadga said, punching each word. “This is a completely new and unprecedented effort—in contravention of international treaties and obligations. It's an explicit effort to make it impossible for people to exercise their legal rights.”On the Brownsville side of the river, a clutch of protestors sits in a small park in vigil. They will stay, they say, until their country recants its crimes. They believe the camp and the desperation it breeds are intentional designs of a government intent on dehumanizing a hated population.Drawing comparisons to the treatment of Jews in the years before the Holocaust, Joshua Rubin, a retired computer programmer from Brooklyn, who is Jewish, says he feels compelled to be a witness, to not look away when his country is doing something wrong. He organized the protest called Vigil at the Border. He and the others will remain, he said, holding their "Let Them In" and "History is Watching" signs until the U.S. reverses the Remain in Mexico policy. "I don't have a lot of hope that that will happen, but I don’t have much choice," Rubin said. "You can't close your eyes and make it go away."Back in Matamoros on a Friday afternoon in late January a hundred people walked into a tent—large and white like something for a wedding except this was about separation not union—sat themselves in rows and listened as two attorneys from the Young Center gave a briefing:Here is the process that will confront your children if you send them over the bridge by themselves. They will be collected. They will be sent to a prison-like detention center. They will be assigned a case number. They will get a calendar date. They will be under the authority of federal agents. They may spend months or years in this facility. They may be sent to foster care. The people with whom they live may or may not speak Spanish. They may be able to connect to your brother, your aunt, your cousin in New York, in Michigan, in California. They may not. You might never see them again.The Hondurans, Salvadorans, Guatemalans, Nicaraguans listened in weary attention. In the front row, a toddler breast-fed luxuriantly, in the way of toddlers, full, entitled, the fingers of his hand splayed proprietarily on his mother’s side. She wiped her eyes repeatedly and blinked hard.Leaning forward, heads inclined and faces stoic, the migrants listened to the lawyers' words. They were not hopeful.Gladis Molina Alt, director of the Young Center's Child Advocacy Program, was herself once a migrant. Her father fled Morazán, El Salvador in the early years of that country’s war, swam the river and got himself to Los Angeles. He sent for her and her brothers and mother later. She arrived in the U.S. at age 10. Became a citizen at 27. Went to law school and now, pulled by history, works as a legal advocate for other migrant children.Today is different though. Ordinarily she works the hard cases of children in detention. Today she is at the other end of the story, speaking to parents in the camp who may have received some very bad advice.An American woman visiting the camp has told families she can get their children into the United States, that within a week they will be with those family members waiting in Maryland or Iowa or Oregon.The woman has no way of ensuring this. No expertise or authority. But families have trusted a heart-sick gringa. They sent their children to stand on a small bridge across the Rio Grande and throw themselves on the anemic mercy of Customs and Border Patrol. It is difficult to learn where those children are today. The federal detention, supervision and child management system is vast and anything but transparent. Still, after the briefing a quiet line forms, then encircles the attorneys, women and men wanting more information.The breast-feeding mother is among them. The next day, climbing out of the tent she shares with her husband and children, holding the happy toddler on her hip while her older child plays soccer in the dust, she explains. The little one is too small to send, but she is worried for the fate of her nine-year-old son in the camp. The kind of people they fled El Salvador to avoid are active here. She knows they'll prey on the boy.It feels like psychological war being kept here, she says: the waiting, the uncertainty. Yet if they return to El Salvador she is sure they will be killed. "I have to think of sending him," she says, crying now. "There is no life here." She and her family are among tens of thousands of Central Americans who’ve fled north in the past decade: 35,000 people from Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras sought asylum at the U.S. border in 2017, the last year for which Department of Homeland Security data was readily available. An additional 75,000 people from those three nations sought asylum when faced with deportation the same year. Asylum claims from the northern triangle of Central America jumped 800 percent between 2012 and 2017 according to DHS’ Annual Flow Report on Refugees and Asylees from March 2019.Holocaust Survivor: Yes, the Border Detention Centers Are Like Concentration CampsThe migrants are driven from nations deformed by brutality, where the social and psychological wounds of wars committed a generation ago festered into drug, gang and government violence today that leaves few families safe. Last week Human Rights Watch released a report documenting cases of 138 Salvadorans who were killed after being deported back into their country.The parents who circled the lawyers after the briefing in Matamoros had similar fears and questions: How long, really, before they get out of detention? My children are gone, how will I find them? What if their claim of asylum has already been rejected? Does that count against them? How will it affect my own case? Is there a way to do something to make it more possible that I might see them again? There is no life here. I cannot take them back to Honduras/El Salvador/Guatemala. We will be killed."It's Sophie's Choice, but you don't get to keep one of them," another lawyer with long experience and red eyes said after she stepped away from a conference you might call a sidewalk conference, but for the fact there was no sidewalk.Only cracked, very dry ground.Read more at The Daily Beast.Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.

from Yahoo News - Latest News & Headlines https://ift.tt/39GPR3H

0 notes

Link

Behind barbed wire, within view of Texas, 2,200 migrants live in a netherworld between U.S. and Mexican responsibility. No one's in charge and amateurs are rushing in to help. Desperate conditions and an abiding despair are forcing awful choices. Some people think that's the point. Leaked Letter Shows Where Military Will Reinforce Trump’s Border WallMATAMOROS, Mexico—In the year since the Trump Administration instituted the Migrant Protection Protocols, known as the Remain in Mexico policy, a sprawling encampment has grown in Matamoros, just a shout across the Rio Grande from Brownsville, Texas. The people here are under the jurisdiction of the United States, although they sleep at the very edge of a country neither their own nor the one they seek. The camp exists between Mexican and U.S. authority and outside international law. It's not an official refugee camp, though it certainly looks like one. Dozens of tents are pitched in rows on the tennis courts and soccer pitch of a city park and covered in black garbage bags to keep out the rain. Men lug plastic hardware-store buckets to collect water. They have built tables out of logs and the flat boards of shipping pallets lashed together with rope. Women pat masa into tortillas and cook on grills over wood fires (park trees chopped down for the purpose). The camp is a waiting room for the U.S. immigration courts, which operate out of a warren of white tents on the Texas side of the river. But the wait is long. Many have hearings set for March or April, five and six months after they first presented their asylum claims. The camp teems with children, young, skinny Central Americans with indigenous faces. On Feb. 1, UNICEF issued a statement saying the agency had begun developing places for the children to play, some basic health screening and organization of water and sanitation services. But these are minimal and belated. Migrants seeking asylum in the United States have been sleeping in Matamoros since July. In the absence of official international system management, social service workers, attorneys, activists, crisis junkies, Silicon Valley millionaires and organized and freelance do-gooders have filled the vacuum. Some have experience responding to crisis. Some have no idea what they are doing. No one is in charge. An Italian tourist is running a photography class for kids. A self-described redneck anarchist is managing logistics and operations: what to do with 100 camp stoves donated by a philanthropist, where to locate the garbage barrels a charity is buying. An evangelical pastor associated with Franklin Graham who runs a hip-hop church in Matamoros is helping organize a council of camp residents to make joint decisions. A clutch of acupuncturists is extolling the trauma-relieving properties of their art.There is no vetting. The volunteers who walk into the camp with some idea of doing good receive no screening or training on the risks that the migrants face. Some take pictures and post to social media long accounts filled with details of migrants' asylum claims. A knot of GoFundMe and Kickstarter pages without accounting safeguards collect donations for a mushrooming variety of initiatives, some well-grounded, some not. Not that there haven’t been efforts to organize and control the chaos. They just haven’t been effective. Since December, Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley, a U.S. group called Angry Tias and Abuela, and others have met weekly with the Mexican immigration authorities. Bria Schurke, a physician's assistant from northern Minnesota, is on her fourth stint in a makeshift health clinic run by Global Response Management, a tiny nonprofit that also has clinics in Yemen, Syria, and Iraq. She worked in refugee camps in East Africa, and is alarmed by the rookies, the lack of ethical protocols governing humanitarian relief in Matamoros. "Because it's accessible a lot of people are showing up, well intentioned or not," Schurke said. Most of the patients Schurke sees in the clinic have respiratory infections or intestinal illnesses, scabies or lice. There is malnutrition, but the most severe malady is fear. The camp inhabitants are popular targets for the drug cartels and human trafficking operations that hold power in Matamoros. Migrants are subject to kidnapping, torture, and rape, according to “A Year of Horrors,” a new report by Human Rights First. It tallied 201 cases of kidnapping and attempted kidnapping of children under the Migrant Protection Protocols.A Feb. 12 report called "No Way Out," from Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières, is equally dire. In October 2019, the report notes, of the patients MSF cared for in one border town, 75 percent had been kidnapped recently.An MSF psychologist and two other workers have been serving migrants in the city of Matamoros since September. At the beginning of February they began working inside the migrant camp with a doctor two days a week. In addition to infections and injuries from exposure, hunger and walking hundreds of miles, MSF staff see truama from abuse suffered along the migrant root and also inside U.S. detention centers.The report called the levels of violence that migrants are fleeing in Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras “comparable to that in war zones where MSF has been working for decades” and “a major factor fueling migration north to Mexico and the U.S.”But admittance into the United States may never come. Returning home is not an option. Conditions are desperate enough that some parents have sent their children across the bridge into the U.S. alone, deciding they are better off in detention centers than the precarity of camp.These are choices parents shouldn't be compelled to contemplate, said Jennifer Nagda, policy director for the Young Center for Immigrant Children's Rights, who visited the camp in January. “There shouldn't be a camp,” Nadga said, punching each word. “This is a completely new and unprecedented effort—in contravention of international treaties and obligations. It's an explicit effort to make it impossible for people to exercise their legal rights.”On the Brownsville side of the river, a clutch of protestors sits in a small park in vigil. They will stay, they say, until their country recants its crimes. They believe the camp and the desperation it breeds are intentional designs of a government intent on dehumanizing a hated population.Drawing comparisons to the treatment of Jews in the years before the Holocaust, Joshua Rubin, a retired computer programmer from Brooklyn, who is Jewish, says he feels compelled to be a witness, to not look away when his country is doing something wrong. He organized the protest called Vigil at the Border. He and the others will remain, he said, holding their "Let Them In" and "History is Watching" signs until the U.S. reverses the Remain in Mexico policy. "I don't have a lot of hope that that will happen, but I don’t have much choice," Rubin said. "You can't close your eyes and make it go away."Back in Matamoros on a Friday afternoon in late January a hundred people walked into a tent—large and white like something for a wedding except this was about separation not union—sat themselves in rows and listened as two attorneys from the Young Center gave a briefing:Here is the process that will confront your children if you send them over the bridge by themselves. They will be collected. They will be sent to a prison-like detention center. They will be assigned a case number. They will get a calendar date. They will be under the authority of federal agents. They may spend months or years in this facility. They may be sent to foster care. The people with whom they live may or may not speak Spanish. They may be able to connect to your brother, your aunt, your cousin in New York, in Michigan, in California. They may not. You might never see them again.The Hondurans, Salvadorans, Guatemalans, Nicaraguans listened in weary attention. In the front row, a toddler breast-fed luxuriantly, in the way of toddlers, full, entitled, the fingers of his hand splayed proprietarily on his mother’s side. She wiped her eyes repeatedly and blinked hard.Leaning forward, heads inclined and faces stoic, the migrants listened to the lawyers' words. They were not hopeful.Gladis Molina Alt, director of the Young Center's Child Advocacy Program, was herself once a migrant. Her father fled Morazán, El Salvador in the early years of that country’s war, swam the river and got himself to Los Angeles. He sent for her and her brothers and mother later. She arrived in the U.S. at age 10. Became a citizen at 27. Went to law school and now, pulled by history, works as a legal advocate for other migrant children.Today is different though. Ordinarily she works the hard cases of children in detention. Today she is at the other end of the story, speaking to parents in the camp who may have received some very bad advice.An American woman visiting the camp has told families she can get their children into the United States, that within a week they will be with those family members waiting in Maryland or Iowa or Oregon.The woman has no way of ensuring this. No expertise or authority. But families have trusted a heart-sick gringa. They sent their children to stand on a small bridge across the Rio Grande and throw themselves on the anemic mercy of Customs and Border Patrol. It is difficult to learn where those children are today. The federal detention, supervision and child management system is vast and anything but transparent. Still, after the briefing a quiet line forms, then encircles the attorneys, women and men wanting more information.The breast-feeding mother is among them. The next day, climbing out of the tent she shares with her husband and children, holding the happy toddler on her hip while her older child plays soccer in the dust, she explains. The little one is too small to send, but she is worried for the fate of her nine-year-old son in the camp. The kind of people they fled El Salvador to avoid are active here. She knows they'll prey on the boy.It feels like psychological war being kept here, she says: the waiting, the uncertainty. Yet if they return to El Salvador she is sure they will be killed. "I have to think of sending him," she says, crying now. "There is no life here." She and her family are among tens of thousands of Central Americans who’ve fled north in the past decade: 35,000 people from Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras sought asylum at the U.S. border in 2017, the last year for which Department of Homeland Security data was readily available. An additional 75,000 people from those three nations sought asylum when faced with deportation the same year. Asylum claims from the northern triangle of Central America jumped 800 percent between 2012 and 2017 according to DHS’ Annual Flow Report on Refugees and Asylees from March 2019.Holocaust Survivor: Yes, the Border Detention Centers Are Like Concentration CampsThe migrants are driven from nations deformed by brutality, where the social and psychological wounds of wars committed a generation ago festered into drug, gang and government violence today that leaves few families safe. Last week Human Rights Watch released a report documenting cases of 138 Salvadorans who were killed after being deported back into their country.The parents who circled the lawyers after the briefing in Matamoros had similar fears and questions: How long, really, before they get out of detention? My children are gone, how will I find them? What if their claim of asylum has already been rejected? Does that count against them? How will it affect my own case? Is there a way to do something to make it more possible that I might see them again? There is no life here. I cannot take them back to Honduras/El Salvador/Guatemala. We will be killed."It's Sophie's Choice, but you don't get to keep one of them," another lawyer with long experience and red eyes said after she stepped away from a conference you might call a sidewalk conference, but for the fact there was no sidewalk.Only cracked, very dry ground.Read more at The Daily Beast.Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.

from Yahoo News - Latest News & Headlines https://ift.tt/39GPR3H

0 notes

Link