#Sharecropping

Text

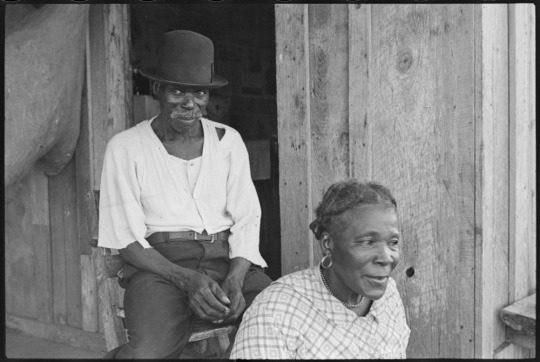

African American Sharecropper on Sunday, Little Rock, Arkansas. October 1935.

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Among the realities that led the Exodusters to flee are the twin faces of the pale ghost of slavery that stalked the South:

The first of these was sharecropping, where Black people in the rural South did in the end wind up working for wages growing cotton in the same reason where their ancestors were enslaved. In parts of the South 1865 and Reconstruction ended up a brief blip that left some traces but otherwise rather less of a break than the 'Sherman FUBARed the South said so.'

This is one of the realities that confronted Black people in the Gilded Age, the period when Americans wound up undergoing their first time where misery in the workplace increased, lives decreased, and profit over human life was pursued to the bitter end.

#lightdancer comments on history#black history month#gilded age#sharecropping#slavery by another name

2 notes

·

View notes

Audio

© 2023 Frank David Leone, Jr./Highway 80 Music (ASCAP). The songs and stories on the Highway 80 Stories website are works of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

Sing With th' Devil in Hell

(F.D. Leone, Jr.)

Shotgun shells

In my vest

Tonight Richard McQuayle

Will meet his death

Blood feud

Decades old

My resolve is shrewd

My blood is cold

His belly out

Thumbs in his bib

Wanted us out

Burnt the corn crib

Pap was a poor man

Him and Pa

Farmed McQuayle land

Who made their own law

My sister, Maysee

We'd run to the trees

Eyes wide with stories

Sacred mysteries

How hard we worked

The crop still failed

Didn't pay the third

We owed to McQuayle

Might of been sincere

Claimed he didn't know

The loft was where

Lil' Maysee would go

A private nook

Away from the boys

With her book

Away from the noise

Burnt up

Along with the corn

McQuayle'll know what

When you burn a barn

The start of a tale

Tonight it'll end

Richard McQuayle

Will meet my friend

Pap's 12 gauge

It's old but it works

Buck shot sprayed

Across his night shirt

Tonight, I swear,

Richard McQuayle

Gonna send you there

To sing with th' Devil in Hell

Night air blazes

Black powder smell

Justice for Maysee, and

Slick Dick McQuayle

David Leone: vocal, guitar

#bandcamp#sharecropping#revenge#indie folk#alt-country#southern fiction#georgia#literature#southern gothic#acoustic

0 notes

Text

Sharecropping: Slavery Rerouted

Though slavery was abolished in 1865, sharecropping would keep most Black Southerners impoverished and immobile for decades to come.

— Published: August 16, 2023 | By Jared Tetreau | The Harvest: Integrating Mississippi's Schools | Article | Sunday August 20, 2023

Sharecropper's children. Montgomery County, Alabama, 1937, photographer Arthur Rothstein, Library of Congress

“The White Folks had all the Courts, all the Guns, all the Hounds, all the Railroads, all the Telegraph Wires, all the Newspapers, all the Money and nearly all the Land – and we had only our Ignorance, our Poverty and our Empty Hands.” — an anonymous Sharecropper, Elbert County, Georgia, ca. 1900

On January 1, 1867 in Marshall County, Mississippi, Cooper Hughes and Charles Roberts entered into an agreement. In their contract with landowner I.G. Bailey, Hughes and Roberts, both formerly enslaved men, agreed to work 40 acres of corn and 20 acres of cotton on Bailey’s land, along with “all other work…necessary to be done to keep [the farm] in good order,” for the duration of 1867. In exchange for their labor, Hughes, Roberts and their families would be “furnished” with stipends of meat, a mule for plowing, a plot of land to grow a garden, separate cabins and one-third and one-half of the corn and cotton crops respectively.

On that first day of 1867, Hughes and Roberts joined a growing number of newly freed African Americans turning toward a new agricultural arrangement in the South. It would come to be called “sharecropping.” In the decades that followed, sharecropping would grow into what scholar Wesley Allen Riddle called the “predominant capital-labor arrangement” in the region, defining how hundreds of thousands of Black Southerners made a living and supported their families. But once up and running, sharecropping itself would deny the formerly enslaved their rights and liberties as free American citizens for nearly one hundred years.

Sharecropper "Mother Lane" Pulaski County, Arkansas,1937, United States Resettlement Administration, photographer Ben by Shahn, Library of Congress

What is Sharecropping?

Sharecropping is a system by which a tenant farmer agrees to work an owner’s land in exchange for living accommodations and a share of the profits from the sale of the crop at the end of the harvest.

The system emerged after the Civil War, when the southern economy lay in ruins. With the Confederate monetary system wiped out, farm land decimated, and slavery abolished under the 13th Amendment, access to labor and capital was extremely limited among Southern landowners. For former slaves, federal proposals to redistribute land fell apart in the 1860s, leaving millions without the promises of full citizenship guaranteed to them by the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments.

Pitched as a solution for both groups, sharecropping was presented to the formerly enslaved as land ownership by proxy. It put an end to work in “gangs” under an overseer, while keeping Black workers within the agricultural sector, preferably on the same land where they had been held captive, and incentivizing high crop yields, benefitting landowners. But even though the old plantation system had changed and some day-to-day activities were delegated to sharecroppers, sharecropping proved a fundamentally unequal arrangement, organized to keep Black farmers from ever achieving economic or social mobility.

As writer Doug Blackmon notes, many white southerners after Emancipation were determined not to pay for something they had once had for free—Black labor.

Many landowners at the end of the Civil War were furious at the idea of paying Black workers whom they’d owned only months before. As a result, landowners developed systems adjacent to slavery. On the plantations, this took the form of sharecropping, though the transformation did not happen overnight.

Black Americans in the South were eager to exercise their newfound freedoms after the war. As historian Wesley Allen Riddle writes, “the most basic and symbolic” of these freedoms was “mobility” itself. The formerly enslaved left their plantations in droves, some looking for work in the South’s devastated cities, while others looked for—and were given by the Union Army—vacant land on which to raise a farm. But work in cities was hard to come by. Only about 4 percent of Freedmen were able to find work in southern cities after the war, and many who came there were relegated to shantytowns of the formerly enslaved. As for those that were given vacant lands by the army, they were forced out when President Andrew Johnson canceled Field Order No. 15 in the fall of 1865, returning these properties to their white owners.

While many formerly enslaved did leave the plantations after the war, many others could not. Those trying to leave faced horrific violence and intimidation from their former owners. As Union General Carl Schurz reported in his testimony to Congress in 1865, “In many instances, negroes who walked away from plantations, or were found upon the road, were shot or otherwise severely punished.”

With land ownership all but closed to them, and urban service work extremely limited, many Freedmen had little choice but to return to the plantations by the end of the 1860s. Their motives for this were mixed. Though economic pressures were strong, many wanted to reunite with loved ones who had been sold during slavery, and saw some appeal in working in an agricultural sector that they were familiar with.

Twenty to 50 acre plots, a cabin to live in and farming supplies were promised to them, all in exchange for about 50 percent of their harvest. Freedmen envisioned a self-sustained life working a plot of land, raising a garden, and providing for their families as they wanted. But these hopes were dashed as the pitfalls of sharecropping quickly became clear.

Sharecroppers, Pulaski County, Arkansas. 1937, photographer Ben by Shahn, United States Resettlement Administration, Library of Congress

Life as a Sharecropper

By design, sharecropping deprived Black farmers of economic agency or mobility. Although they were no longer legally enslaved, sharecroppers were kept in place by debt. As their income was dependent on both the profits from the sale of the crop and the whims of the landowners, sharecroppers had to find means to sustain themselves during the rest of the year. They were forced to purchase food, seed, clothing and other goods on credit, typically from a plantation “commissary” owned by the landlord.

At the end of the harvest, when revenue from the crop was “settled up,” the sharecroppers’ portion of the profits was calculated against their debts. As a result, sharecroppers often ended the year owing their landlords money. What could not be paid off was carried into the next year, creating a cycle of indebtedness that was often impossible to break.

Sharecroppers in debt to their landlord were subject to laws that tied them to the land. If they attempted to move, any new tenancy contracts they signed with other landlords could be voided by their existing ones. If they ran away, they could be brought back to their landlord in chains, and made to work as a prisoner for no pay at all.

Even if sharecroppers did not try to leave, they still faced massive obstacles in achieving any kind of solvency. For instance, many Southern states limited how and to whom sharecroppers could sell their part of the crop. In Alabama, cotton had to be sold and transported during the day, and could only be purchased by a state-defined “legitimate” merchant. As sharecroppers couldn’t afford to lose a day’s work to take their crop to market, these laws curtailed their ability to sell their product at the best possible price.

In addition, individual freedoms were crushed by tenancy contracts, many of which included arbitrary clauses forbidding alcohol consumption, speaking to other sharecroppers in the fields or allowing visitors on rented land.

Black sharecroppers could not seek redress through the political system either. Despite the ratification of the 14th and 15th Amendments, the southern “Redemption” that followed the withdrawal of Union troops from the South in 1876-7 ensured that the federal government would not enforce Black voting rights. Black elected officials disappeared from Congress and state legislatures, and attempts at organizing Black voters were brutally suppressed, as in New Orleans in July of 1866, where a convention of Black voters was attacked by a white mob under police protection that killed an estimated 200 people.

Educational opportunities were also sparse. In 1872, white Southerners pressured Congress to abolish the Freedmen's Bureau, a federal agency designed to provide food, shelter, clothing, medical services and land to newly freed African Americans. With the dissolution of the Bureau, few resources remained for the approximately 80 percent of Black people who were illiterate.

Sharecropping, with its prohibitive restrictions on physical and economic mobility, its use of violence and intimidation and its emphasis on maximum production, denied Black Southerners the ability to gain wealth, to exercise the freedom granted them by Emancipation and to gain the education they were deprived of during enslavement. The system existed, in conjunction with other institutions, to exploit Black labor at a minimum “relative loss” to white landowners while keeping the Black population underfoot.

As Black sharecropper Ed Brown said of his experience, “hard work didn’t get me nowhere.”

Sharecropper's cabin, Southeast Missouri Farms. 1938, photographer Russell Lee, Library of Congress

Sharecropping’s Decline and Legacy

After dominating the southern agricultural economy for decades, sharecropping was, like most other farming practices, upended by the rise of new technologies. While these changes were delayed by the Great Depression, sharecropping had become obsolete in many areas of the South by the mid-twentieth century. With increased mechanization, white planters’ demand for Black labor dried up.

Also during this time, Jim Crow obstructions to Black enfranchisement, as well as state-sanctioned violence against Black people, were directly challenged by the Civil Rights Movement and the landmark legislation it helped enact. The Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1968 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 deconstructed de jure segregation across the South in housing and public accommodation, while empowering the federal government to secure the right to vote for Black Southerners.

As scholars Paru Shah and Robert S. Smith note, enfranchisement, desegregation and the decline of sharecropping weakened “the broader agenda of White Supremacy to crush African American socioeconomic mobility,” but did not destroy it. The effects of centuries of Black economic and social oppression, represented in part by sharecropping, are still felt today. Limited access to capital, to mobility, and to representation during Jim Crow and before it denied Black Americans the ability to save, invest or accumulate wealth, concentrating inherited fortunes in the hands of white families and shaping the present class makeup.

For nearly a century, sharecropping defined Southern agriculture and hindered Black economic advancement. The system reflected a multidude of attempts by the white power structure to keep Black workers stagnant, achieving this through intimidation, physical violence and exploitation. Ultimately, aided by organized action, shifting technological and economic conditions and the determination of sharecroppers themselves, the oppressive reality of sharecropping ended. But in the endemic inequities of American political and economic life, its legacy persists.

#NOVA | PBS#Sharecropping#Slavery Rerouted#Black Southerners#The Harvest#Integration#Mississippi's Schools#Jared Tetreau#Article#White Folks | Possessor of Courts | Guns | Railroads | Telegraph Wires | Newspapers | Money | Land#Marshall County | Mississippi#Cooper Hughes | Charles Roberts#Landowner | I.G. Bailey#Sharecropper | Ignorence | Poverty | Empty Hands#African Americans#Civil War#Confederate Monetary System#Doug Blackmon#Emancipation#Historian | Wesley Allen Riddle#Union General Carl Schurz#Southern States | Alabama#Redemption#Educational Opportunities#Freedmen's Bureau#Black Sharecropper | Ed Brown#Civil Rights Movement#Civil Rights Acts of 1964 & 1968 | Voting Rights Act of 1965#Scholars: Paru Shah | Robert S. Smith

0 notes

Text

Women Farmers and Entrepreneurs in Rural and Small Town India

FWWB, Ahmedabad provides micro-finance to organisations and women entrepreneurs and is engaged in capacity. We visited Viramgam and Kadi, to meet women farmers and entrepreneurs.

View On WordPress

#beautypreneurs#farmers#FWWB#micro-finance#Saath#sharecropping#small town#village#women entrepreneurship

1 note

·

View note

Text

one thing i haven't thought about in a while is how my bat mitzvah drash was about how everyone kinda wants to be told what to do. girl...

#no this is a slight misrepresentation for the sake of humor#it was about the terrifying freedoms of adulthood and also ancient egyptian sharecropping#and it was kinda bad#txt

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

listening to the album The Band for the first time and it's like. writing a sad confederate song in the year 1969 is crazy. it has been over a century. you've just been through almost two decades of the civil rights movement. what do you mean "I remember taking him to the library so he could research the history and geography of the era and make General Robert E. Lee come out with all due respect." you do not have to do that The Band.

#two of the 11 confederate states had more than half their populations enslaved The Band!!!#sharecropping as a system was only fully dying out when you guys were born The Band!!!!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

fun fact re: that last ask but i actually have a folder in my browser's bookmarks bar titled "wool" bc for the longest time i was like i'm going to do research on germany's wwi wool industry and incorporate that into fullmetal alchemist fanfic like i was so invested..

#i think i managed to find a hundred page academic article specifically detailing the progress or lack thereof#of the industry from 1910 to 1917 like i'm pretty sure it's the last pdf up there lmao..#to be deleted#the what is sharecropping.. embarrassingljkdsafdsgdsfhgf

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

#colonialism#new age sharecropping#vital community#vital information exchange#vitalportal#additional information#thevitalportal#vital media#blacklivesmatter#blacktwitter#vital politics#myvitaltv

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

just discovered colter wall and wanted to know if you’ve listened to him sinse you’re into country 👀 he’s got a bery cool voice, someone said his music was more of a hobby and he mainly worked as a farmhand

omg yeah!!!!!!!!! i've got two of his songs in my playlist omg

youtube

youtube

but beyond that i haven't listened to him much, so I'll have to check out more of his stuff! i rlly like these two songs a lot ❤️

#his description of the devil as a white man in a suit and tie coming to offer the speaker a bad deal is sooooooooooooooooo#and the description of him being white as a cotton field and sharp as a knife.......#cotton fields as imagery is a rlly loaded thing in the us south bc it's associated w slavery and sharecropping#but i always personally liked here in association with the devil bc it further leans on that terrible context#esp combined w the devil being the white man in a suit with a bad deal that he tricks the speaker into#always felt like that was brilliant and sort of twist on how white artists typically involve cotton fields#in a very problematic nostalgic way :/#anyway that was a random skip on the surface of southern history 😭#the asks and the answers#music

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

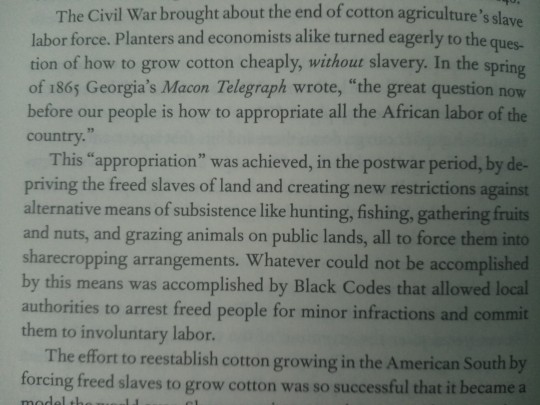

so a while ago, I remember seeing someone European mention how they have very different cultural expectations than the US around trespassing and generally you can wander around on land that belongs to someone else as long as you're not hurting anything

currently I'm reading this book on clothing history and uhh putting some pieces together on that front

like oh. it's because of efforts to force freed slaves back into basically slave labor, at least in part. that's fucking abhorrent.

#dgmw i already knew about the evils of sharecropping & all the scheming to prevent black people from owning land#i just hadn't connected it to this particular phenomenon before

1 note

·

View note

Text

Comendo o cu da coroa gostosa

Orgasmo ed un immensa grande pisciata per quella troia di tua madre

Babes Gina and Whitney loves pussy fingering and licking

Needy young amater shares dick with mamma in amateur clip

salome salvi hard fucked by charles delgado (tinyurl⋅com/SALSAL16)

Hot two lesbian young girls licking pussy and masturbating live on camera

House of taboo and daddy public sex Sneaky Father Problems

minha loira tocando siririca com a bucetinha melada

Coed Nicole cum sprayed after hardcore casting penetration

view royal casino 1708 island hwy victoria bc v9b 1h8

#metabolic#self-supported#knobber#scrobe#associationalism#snugger#forwrap#pseudoaristocratic#codevelops#nonvehement#unprayed#aspersoria#sharecropped#roastable#stallenger#uneated#syllabicity#semiphilosophically#pignolis#Flacianist

0 notes

Text

Pretty brunette Marina Angel gets fully satisfied

Chastity slave licks Mistress E's delicious pussy to orgasm while she plays with clit sucker toy

Porn gay male men mechanical fags orgy Bathroom Bareback Boypatrons

Damn hot Transbabe friends Aspen and Khloe loves butt sex

Spex gilf pussylicked by amateur teen

Hot MILF Brandi Love Says "Do you like watching me stroke your friend?!" S1:E2

Gaping hOle indian ass

Kama Kama Sutra Power

Huge Boobed Maggie Green & Milf Rachel Storms Eat That Cunt!

Cuzzin fat ass

#sharecrop#lamster#anterofrontal#pulgada#Constantino#Mahmud#unduly#morabit#generalisable#theology#chuting#incivic#sensimotor#terrific#txt#overproved#antimonious#humdrums#EEM#affile

0 notes

Text

"Trust Is A Weakness" brainstorming pt. 1

grabbed some ideas from @witchygod's god-tier post about Radioapple dancing, hurt comfort, etc. and ran with it.

Onward with the brainstorming!

Alastor's alive background:

While Alastor was drafted into WW1, due to him being “colored”, the government put him in the reserves until higher ups realized that he could speak French as was good with technology. He was made a radio operator so the troops in the trenches could communicate with the recon planes.

Alastor 100% killed his father when he was alive. He did it again when he got to Hell. In fact, he was his first kill in both worlds. Oddly poetic, if you asked him.

Due to being a radio host, the depression didn’t really hit him the way it did others. and he wasn’t exactly rolling in cash anyway, so he just sat back and watched the cotton and sugar industry crash and burn. Suits those aristocratic types right for rolling in the riches that his grandmother and great grandmother bled over. He’s just thankful that his sweet mother didn’t have to suffer that fate, leaving the sharecropping behind for a nicer life as a seamstress and cook.

Alastor killed a bunch of people, hiding their bodies in the bayou for the crocodiles to eat throughout his mid-twenties and early-thirties. It’s a pity that he had to get shot. He was just coming back from giving a treat to one of his favorite ones, she was so good at eating all the evidence.

part 2

#hazbin hotel#hazbin alastor#alastor#hazbin lucifer#lucifer magne#radioapple#qpr radioapple#radiosilence#one sided radiostatic#Trust Is A Weakness AU

76 notes

·

View notes

Note

So one thing that irks me about discussions of the NCR is the idea that "they're flawed because they're trying to be America again. And Being Too Much America is what caused the War" without differentiating between the vast buildup of Nuclear Weapons and Geopolitical tensions, versus, like, being a republic and having a large-scale central state.

What's your thoughts?

I think the NCR circa New Vegas is textually intended to be repeating the USA's downward spiral. They're in the process of recreating the core dynamics of pre-war America- overconsumption of resources driving imperialist expansion, capture of the government by moneyed interests, and a prolonged conflict with a peer power that's suffering under similar expand-or-die pressures- but they're constrained from a one-to-one recreation mainly by the fact that they're working with a post-apocalyptic resource base, with the scraps left over from the last people who went down this path. Peanuts compared to the Sino-American war, but likely as close to that situation as the post-war-world is logistically capable of producing.

You see bits of this from the NCR perspective all throughout the game. There Stands the Grass is propelled by projections of incipient famine in the NCR due to rapid population growth, and you see the beginnings of this in Flags of Our Foul-Ups- O'Hanaran was sent to the Army by his family to lessen their food burden. Chief Hanlon's very first line is about how the NCR is overtaxing most sources of freshwater within the core territory, and he recounts how tiny groups of settlers backed by NCR logistics were able to take and hold a well in Baja against scores of locals; IIRC there's a cut event at Camp Golf itself where you'd see NCR rangers doing the same thing to Mojave locals encroaching on their water supply. The White Wash demonstrates that the NCR's sharecropping setup in outer Vegas operates at the expense of the locals, who can only get the water they need to support their own crops via subterfuge. If you assume that Heck Gunderson's underhanded Brahmin-farming empire in Beyond the Beef is supposed to parallel the real-world problems with the sustainability of beef farming, you start to get a sense of where all of that water is going and what structural problems (Heck Gunderson) might be in the way of allocating those resources more sustainably. There are likely more examples of this storm on the horizon that I'm forgetting.

As a result of all this, there's a level on which I think introducing the Tunnelers in Lonesome Road as a dangling White-Walker style Looming Apocalyptic Reset Option hanging over the west coast was gratuitous, not because it's Avallone grinding his axe with the idea of society rebuilding, but because it's simply redundant with the political situation already depicted in the base game- If you want the NCR to have collapsed by a future installment, just establish that they weren't able to put the brakes on in time and devolved into a completely dysfunctional oligarchy that collapsed under its own weight!

(Now, as a final note, one thing preventing me from fully committing to this take is that we honestly don't have a fantastic sense of what day-to-day life looks like for the average citizen in the NCR heartland, which I feel is kind of important. Because if the textual situation is supposed to be that the resource crisis is due to misallocation due to interests capturing the government, I like that a lot better than if the situation is genuinely intended to be that there are Just Too Many Goddarn People, because that's like. Lazy and Malthusian and leads to the usual ugly conclusions pretty quickly. More and more it's looking like the upcoming Fallout TV show is leaning into the recent decline of the NCR as a plot point, so, uh, fingers crossed they stick the landing when it comes to fleshing that out?)

#fallout#fallout new vegas#NCR#new california republic#ask#asks#thoughts#meta#sorry for the delay in responding- getting back into a fallout mood due to the show#fnv

63 notes

·

View notes