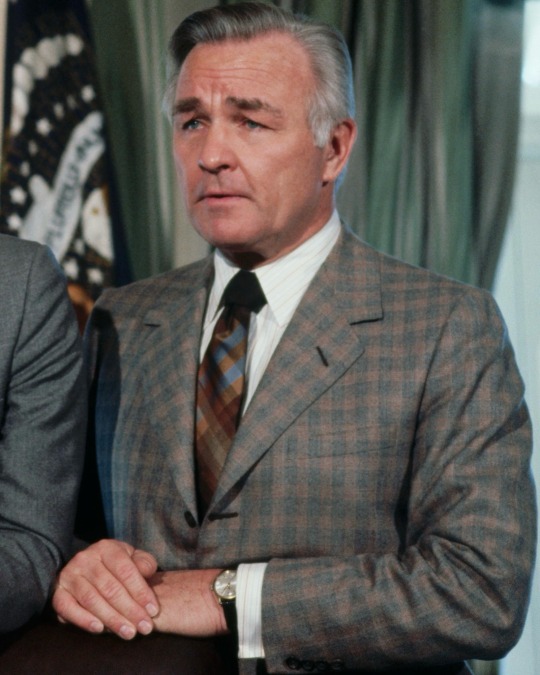

#Stansfield Turner

Text

Stansfield Turner

#suitdaddy#suiteddaddy#suit and tie#suited daddy#men in suits#daddy#suited grandpa#suitedman#silverfox#suit daddy#suitfetish#three piece suit#suited men#buisness suit#suited man#suitedmen#americans#cia director#Carter administration#Stansfield Turner

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

My father knew the inside scoop. My Dad, Butch Sheffield, was with the SR 71 program from cradle to grave and wrote down in his unpublish book some of his reasons why it was canceled prematurely.

During the Carter Administration, 1977-81, while Stansfield Turner was Director of the CIA, the two of them made a decision to rely upon National Technical Means (NTM) or Spy Satellites for intelligence. This included eliminating manned aircraft and spies on the ground. This has been proven to be one of the biggest intelligence mistakes ever.

The reason for this strategy was it was risk-free for the political Administration. No airplanes or spies could be captured and displayed like Francis Powers and the U-2. This made the politician feel comfortable.

NSA National Security Agency never liked the SR-71. Why? It did not collect Communications Intelligence’s (COMINT)! It went too fast for COMINT. Ninety percent of NSA executives came from a COMINT background. They thought that COMINT was the only kind of intelligence that was useful.

All the time I was Recce. Chief, they (the NSA) came to the Pentagon in groups to try to insult the SR 71 program in any way, they could. You would attend a meeting, and one or two people would attend from each service and DOD. NSA would show up with ten people. I would ask why. They would say that each one represents an area of NSA. It was a joke in the Pentagon. I would only let one at a time in my area.

They would tell the White House in a flash-type message that an SR was almost intercepted by a Foxbat when the Foxbat was three hundred miles away from the SR. These types of messages were never followed up with the truth, from NSA, that they had been wrong. They often were.

The cost of this, National Tactical Means (NTM) has never been made public; in fact, most people with security clearances inside the government don’t know the cost. I knew because I I knew because I got a copy, one of twelve printed each year by the NRO, telling the real cost of: the satellite, the launch cost, the communications cost and the ground station cost.

The cost was enormous. The NRO did not want to give me the book. I knew it existed and asked for it. Finally, they gave it to me after I pressured the Director when I worked for the U S Congress.

One might ask how did this affect the SR-71? The answer is that once this very large amount of money was being spent on satellites, they no longer wanted to fund the SR—the SR then went from a National collection platform to a tactical intelligence asset.

Col Richard “ Butch” Sheffield

@Habubrats71 via X

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

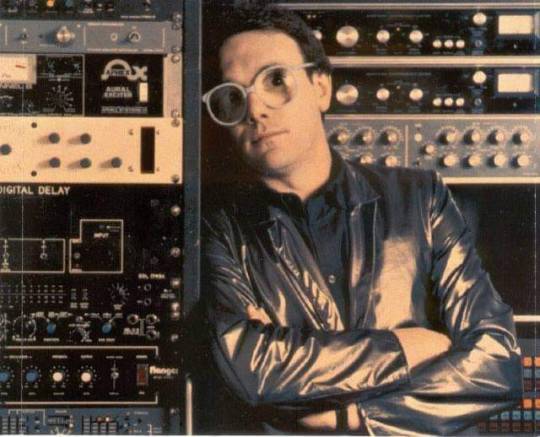

Trevor Horn

Grace Jones, Tina Turner, Robbie Williams, Lisa Stansfield, Pet Shop Boys, Simple Minds, Seal, Whitney Houston, t.A.T.u., Eros Ramazzotti, Mike Oldfield, Seal ,The Buggles (Member), Yes (Drama), Hurts ,Propaganda , Frankie Goes to Hollywood, Art of Noise (Member) , ABC ...

This IS the man, the producer who defined the 80's. Someone many tried to copy. Also responsible for the evolution onto the sound of the 90's, the designer of the Euro sound, and responsible for some of the most creative productions and some of the most creative use of both synthesizers and samplers in music history. Great bass player too!

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

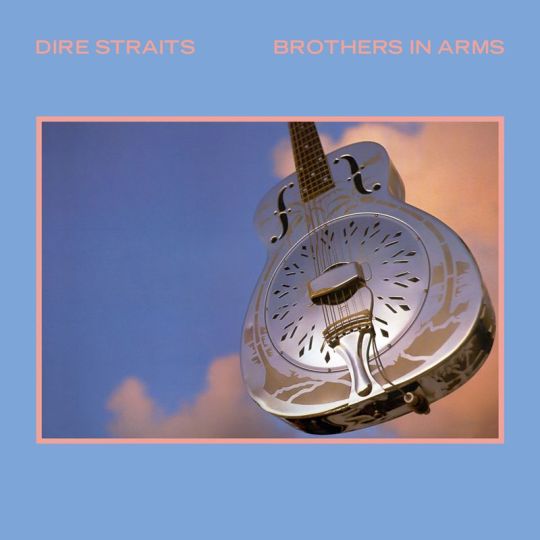

Cappelle Calling - 15 april 2024

Vandaag schoof een toekomstige nieuwe collega van Regio90 bij mij aan in Cappelle Calling: Danique Vukman. Op 1 mei start zij op 90FM met haar nieuwe programma Radio Da Da. Zij stelde vanavond alvast de playlist samen en koos als LP van de Week het album 'Brothers in Arms' van Dire Straits uit 1985.

Terugluisteren kan hier.

Dit was de playlist:

Uur 1:

Creedence Clearwater Revival - Have You Ever Seen the Rain

Ariana Garde & The Weeknd - Save Your Tears

Lisa Stansfield - All Around The World

Dire Straits - Money For Nothing (LP van de Week)

Fleetwood Mac - Rhiannon

Christian Walz - Wonderchild

Florence + the Machine - Stand By Me (DisCovered)

Bryan Adams & Tina Turner - It's Only Love

Barbra Streisand - The Way We Were (Filmplaat - uit 'The Way We Were' )

10cc - The Things We Do For Love

Dire Straits - Your Latest Trick (LP van de Week)

Uur 2:

The Outfield - Your Love

Maan & Goldband - Stiekem

Dire Straits - Why Worry (LP van de Week)

Pearl Jam - Black

Ben E. King - Stand By Me (DisCovered)

Bee Gees - Paradise

Cock Robin - The Promise You Made

Prince - Money Don't Matter 2 Night

Dire Straits - Brothers In Arms (LP van de Week)

Vaya Con Dios - Heading For A Fall

Patrick Bruel - Casser La Voix (live)

Cappelle Calling is iedere maandagavond van 20:00 t/m 22:00 te horen op Radio 90FM. Iedere woensdagmiddag wordt de uitzending herhaald van 18:00 tot 20:00. Suggesties voor DisCovered of De Filmplaat zijn welkom via de Facebookpagina van het programma of via [email protected].

0 notes

Text

1990 • Musical Memoirs Of Millennials

01. Sinéad O'Connor - Nothing Compares 2 U [4:41]

02. Phil Collins - I Wish It Would Rain Down [5:28]

03. Lisa Stansfield - All Around The World [4:26]

04. Sydney Youngblood - Sit And Wait [4:01]

05. Dusty Springfield - In Private [4:23]

06. Milli Vanilli - I'm Gonna Miss You [3:59]

07. Kylie Minogue - Tears On My Pillow [2:30]

08. Del Amitri - Nothing Ever Happens [3:54]

09. Cher - Just Like Jesse James [4:06]

10. Tina Turner - I Don't Wanna Lose You [4:14]

11. Rod Stewart - Downtown Train [4:40]

12. Belinda Carlisle - La Luna [4:44]

13. Madonna - Dear Jessie [4:22]

14. Quincy Jones (feat. Ray Charles & Chaka Khan) - I'll Be Good To You [4:55]

15. Kaoma - Lambada [3:29]

16. Arthur Baker (feat. Al Green) - The Message Is Love [6:22]

17. Laid Back - Bakerman [4:42]

18. Billy Joel - We Didn't Start The Fire [4:48]

19. Jimmy Somerville - You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) [5:16]

20. Technotronic - Get Up (Before The Night Is Over) [3:28]

Listen on Spotify or Youtube or even better download as 320 Kbp/s mp3 files. Use firatavci.com when RAR archive asks for password to extract files.

P.S. Before you download, can you do a little favor? Please use this link and sign up for a free MediaFire account. If you already have a MediaFire account with your primary email address, please sign up with a different email address. MediaFire will give you and me an extra 1 GB quota for free when you sign up using this referral link. So we can keep these carefully selected files alive for download without hitting bandwidth barriers. Thanks in advance.

INTRO • 1990 • 1991 • 1992 • 1993 • 1994 • 1995 • 1996 • 1997 • 1998 • 1999

#musical#memoirs#millennials#gen y#generation y#1990#1990s#pop#music#hits#playlist#retro#archive#nostalgia#nostalgic#spotify#youtube#mp3#download

0 notes

Text

Top Songs of 1989 - Hits of 1989

Top Songs of 1989 - Hits of 1989

Top Songs of 1989 including: Aerosmith - Janie's Got A Gun, Alannah Myles - Black Velvet, Alice Cooper – Poison, Bangles - Eternal Flame, Bee Gees – One, Belinda Carlisle - La Luna, Billy Joel - We Didn't Start the Fire, Bon Jovi - I'll Be There For You and many more! Subscribe to our channel to see more of our content! 1. Aerosmith - Janie's Got A Gun 2. Alannah Myles - Black Velvet 3. Alice Cooper - Poison 4. Avalanche - Johnny, Johnny come home 5. Bangles - Eternal Flame 6. Bee Gees - One 7. Belinda Carlisle - La Luna 8. Big Fun - Can't Shake The Feeling 9. Billy Joel - We Didn't Start the Fire 10. Blue System - Magic Symphony 11. Bon Jovi - I'll Be There For You 12. Bon Jovi - Lay Your Hands On Me 13. Camouflage - Love Is A Shield 14. Cher - If I Could Turn Back Time 15. Chris Rea - The Road To Hell 16. Cyndi Lauper - I Drove All Night 17. David Hasselhoff - Looking for Freedom 18. Debbie Gibson - Lost In Your Eyes 19. Depeche Mode - Personal Jesus 20. Dinamita pa los pollos - Pandilleros 21. Donna Summer - This Time I Know It's For Real 22. Edoardo Bennato - Viva la mamma 23. Elton John - Sacrifice 24. Fine Young Cannibals - She Drives Me Crazy 25. François Feldman - Les Valses de Vienne 26. Gloria Estefan - Don't Wanna Lose You 27. Guns N' Roses - Patience 28. Hanne Haller - Mein lieber Mann 29. Holly Johnson - Americanos 30. Hombres G – Voy A Pasármelo Bien 31. Janet Jackson - Miss You Much 32. Jason Donovan - Every Day (I Love You More) 33. Jason Donovan - Sealed with a Kiss 34. Jive Bunny & The MasterMixers - Swing The Mood 35. Kaoma - Dançando Lambada 36. Kaoma - Lambada 37. Kylie Minogue - Never Too Late 38. Kylie Minogue and Jason Donovan - Especially For You 39. La Unión – Maracaibo 40. Leandro e Leonardo - Entre Tapas e Beijos 41. Lisa Stansfield - This Is The Right Time 42. Locomía - Locomía 43. Madonna - Cherish 44. Madonna - Express Yourself 45. Madonna - Like A Prayer 46. Martika - Toy Soldiers 47. Metallica - One 48. Michael Jackson - Leave Me Alone 49. Milli Vanilli - Girl I'm Gonna Miss You 50. Mysterious Art - Das Omen (Teil 1) 51. NENA - Wunder Gescheh'n 52. Paul McCartney - My Brave Face 53. Phil Collins - Another Day In Paradise 54. Philippe Lafontaine - Cœur de loup 55. Poison - Every Rose Has Its Thorn 56. Queen - Breakthru 57. Queen - I Want It All 58. Richard Marx - Right Here Waiting 59. Riva - Rock me 60. Rocco Granata - Marina Remix 61. Roch Voisine - Hélène 62. Roxette - Dressed For Success 63. Roxette - The Look 64. Roy Orbison - California Blue 65. Roy Orbison - You Got It 66. Samantha Fox - I Only Wanna Be With You 67. Simply Red - If You Don't Know Me By Now 68. Sonia - You'll Never Stop Me Loving You 69. Soulsister - The Way To Your Heart 70. Tears For Fears - Sowing The Seeds Of Love 71. Technotronic - Pump Up The Jam 72. Texas - I Don't Want A Lover 73. The Cure - Lovesong 74. The Refrescos - Aquí no hay playa 75. Tina Turner - I Don't Wanna Lose You 76. Tina Turner – The Best 77. Tom Jones & Art Of Noise - Kiss 78. Tom Petty - Free Fallin' 79. Wet Wet Wet - Sweet Surrender 80. Zucchero - Diavolo In Me Related Searches: Greatest Hits of 1989, Best Jukebox 1989 Playlist, Late 1989 Non Stop , Top 1989 Non Stop, Mix 1989 Compilation, Best 1989 List, Late 1989 UK, Best 1989 Playlist, Best 1989 Non Stop, Best 1989 Video, Greatest 1989 Non Stop, Mix 1989 Playlist, Best Jukebox 1989 List, List of 1989 Mix, Top 1989 USA, Best Songs of 1989, Top Music 1989, Hits of 1989 Relate Hashtags: #songsof1989 #hits1989 #songs1989 #listof1989mix #hits1989 #bestsongs1989 #classic1989playlist #greatest1989nonstop #best1989list #best1989video #top1989mix #greatest1989video #mix1989playlist #top1989nonstop #mix1989compilation

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QOQ4AqIGrCs

#80S Greatest Hits#Songs Of 1980S#Old Songs#80S Songs#80S Music Hits#80S Hits#80S Songs Playlist#Grea

1 note

·

View note

Text

Armas en manos de civiles.

[Militarización de la policía]

El 3\23\94 WASHINGTON POST informó: “El Pentágono y el Departamento de Justicia acordaron compartir tecnología militar, incluidas armas de energía dirigida, con agencias civiles encargadas de hacer cumplir la ley para su uso en los campos de batalla urbanos de Estados Unidos. (2)

[... y sin embargo... Más humanos controlando a distancia]

En la década de 1970, en la revista de derecho Crimen y Justicia, un artículo titulado “El uso de la electrónica en la observación y el control del comportamiento humano y su posible uso en la rehabilitación y el control” decía: “En un futuro muy cercano, una tecnología informática hará posible alternativas al encarcelamiento. El desarrollo de sistemas para telemedir información de sensores implantados en o sobre el cuerpo pronto hará posible la observación y el control del comportamiento humano sin contacto físico real... será posible mantener vigilancia las 24 horas sobre el sujeto e intervenir electrónica o físicamente para influir y controlar el comportamiento seleccionado. Así será posible ejercer control sobre el comportamiento humano y desde la distancia sin contacto”. (Kieth pág. 102) (1)

[Un presidente para el pueblo]

Cuando Jimmy Carter se convirtió en presidente en 1976, rápidamente se movió para introducir un mínimo de control, instituyó la Ley de Vigilancia de Inteligencia Extranjera estableciendo un tribunal secreto de 11 miembros para supervisar las actividades de vigilancia de nuestras agencias encubiertas... El movimiento de Carter para reformar la CIA fue nombrar un extraño como jefe de la agencia, el almirante Stansfield Turner. Después de que Turner asumiera el cargo de Director de la CIA, 800 agentes “pícaros” fueron despedidos, aunque la mayoría de ellos encontró trabajo en varias empresas de fachada falsa que se habían establecido en los años anteriores. 84 (6)

…restricciones más estrictas sobre los experimentos con humanos, incluida la rendición de cuentas y la transparencia, no ocurrieron hasta 1997, cuando el presidente Clinton instituyó protocolos revisados sobre experimentos con humanos.87 (6)

Los rusos prohibieron todas las armas EMF en 2001. (6)

[ El levantamiento del estado policial ]

En marzo de 1993, el Instituto Nacional de Justicia (NIJ, Departamento de Justicia), emitió un informe titulado: “Iniciativa del NIJ sobre armas menos que letales”, que detalla la campaña para armar a las fuerzas del orden estatales y locales con armas dirigidas. -armas de energía para uso en asuntos domésticos. (2)

#armas#armas psicotronicas#oculto#tortura#control#mkultra#linkercargado#uruguay#tortrua#lesa humanidad

1 note

·

View note

Text

LÁZARO, es el nombre del sacerdote, Rolando Alvarez, en lo expedientes desclasificados de la CIA. "El manual preparado por la Agencia Central de Inteligencia (CIA) para las fuerzas anti sandinistas, está basado en guerra psicológica, utilizada por el Ejército de EE.UU durante la guerra de Vietnam", dijo ayer a la cadena de televisión norteamericana ABC, el Senador Demócrata John Patrick Moynihan.

LA INTERVENCIÓN NORTEAMERICANA EN NICARAGUA, FUÉ CRITICADA EN LA MISMA EMISORA, POR 2 EX DIRECTORES DE LA CIA. El senador demócrata aseguró que el documento preparado para los antisandinistas incluía, "palabra por palabra", párrafos de las instrucciones puestas en práctica por las tropas estadounidenses en 1968. Moynihan aceptó que el manual para la lucha contra el "RÉGIMEN" de Nicaragua, no menciona explícitamente el asesinato de dirigentes políticos, "pero sí HABLA DE CONTRATAR A DELICUENTES COMUNES, PARA LLEVAR A CABO DETERMINADOS TRABAJOS Y "NEUTRALIZAR", término habitual, por DAR MUERTE, en el lenguaje de la Agencia de Espionaje. El almirante Stansfield Turner, director de la CIA entre.1976 y 1980, declaró que "lo que está sucediendo, es que LOS AGENTES DE LA CIA, RECURREN A CIERTAS ACTIVIDADES, CUYA LEGALIDAD ES MATERIA DE DISCUSIÓN, LO QUE PUEDE PERJUDICAR A LA AGENCIA". Otro antiguo máximo responsable de la agencia de espionaje norteamericana, William Colby, que dirigió la CIA durante las administraciones de los presidente Richard Nixon y Gerald Ford,consideró que "LA AYUDA A LOS CONTRAS (GRUPOS GUERRILLEROS ANTI

SANDINISTAS) DEBILITA NUESTRA ESTRATEGIA EN EL ÁREA".

Fuente: EL PAÍS

0 notes

Text

Stansfield Turner, who led major CIA reforms, dies - Thu, 18 Jan 2018 PST

Stansfield A. Turner, who served as CIA director under President Jimmy Carter and oversaw reforms at the agency after the Senate uncovered CIA surveillance aimed at American citizens, has died. ...

Stansfield Turner, who led major CIA reforms, dies - Thu, 18 Jan 2018 PST

0 notes

Text

On this date in music!

April 20th

1949 - Phil Spector

Phil Spector's father commited suicide when Phil was just 9 years old. The title of the song 'To Know Him Is To Love Him,' which Phil Spector wrote for the Teddy Bears, (the only vocal group of which he was a member), comes from the inscription on his father's headstone.

1957 - Elvis Presley

Elvis Presley started an eight week run at No.1 on the US singles chart with 'All Shook Up.' It went on to be the biggest single of 1957 selling over 2 million copies.

1959 - Dolly Parton

Goldband Records released 'Puppy Love' by a 13-year old Dolly Parton in the US, a song that was recorded two years earlier when she was just eleven years old. The song didn't chart.

1968 - Deep Purple

Deep Purple made their live debut at a gig in Tastrup, Denmark. Formerly known as Roundabout, guitarist Ritchie Blackmore suggested a new name: Deep Purple, named after his grandmother's favourite song (which had been a hit for Peter De Rose), after his grandmother had repeatedly asked if they would be performing the song.

1971 - 420

Five friends at San Rafael High School in California coined the term "4:20" as a euphemism for smoking pot. April 20th became a popular day to spark one up, as does 4:20pm. Fans of the Grateful Dead helped spread the phrase, the Boston song 'Smokin'' clocks in at 4 minutes, 20 seconds, and if you multiply the title numbers in Bob Dylan's 'Rainy Day Women #12 And #35,' you get 420.

1976 - George Harrison

George Harrison, who is good friends with Eric Idle, joined Monty Python on stage at New York's City Center. Dressed as a Canadian Mountie, Harrison joined the chorus for 'The Lumberjack Song.' No mention was made of Harrison's appearance, and few in the audience recognised him. The next night, Harry Nilsson showed up to perform the same feat, but with disastrous results, as he fell into the audience and broke his arm.

1980 - George Burns

84 year old George Burns, who starred in the movie Oh God with John Denver, became the oldest person to have a hit on the Billboard Hot 100 when 'I Wish I Was 18 Again' peaked at No.49. When asked if he wished he were 18 again, Burns replied "I wish I was 80 again." Before this, his most recent charting record had been a spoken word comedy routine with his wife and partner Gracie Allen in the summer of 1933.

1981 - John Phillips

John Phillips of The Mamas & the Papas was jailed for five years after pleading guilty to drug possession charges; the sentence was suspended after 30 days. Phillips started touring the US lecturing against the dangers of taking drugs.

1985 - Bruce Springsteen

The charity record 'We Are The World' by USA For Africa was at No.1 on the UK singles chart. The US artists' answer to Band Aid had an all-star cast including Stevie Wonder, Tina Turner, Bruce Springsteen, Diana Ross, Bob Dylan, Daryl Hall, Huey Lewis, Ray Charles, Billy Joel and Paul Simon plus the composer's of the track, Michael Jackson and Lionel Richie.

1991 - Steve Marriott

Steve Marriott leader of Small Faces and Humble Pie, died in a fire at his home in Essex. His work became a major influence for many 90s bands. Small Faces had the 1967 UK No.3 & US No.16 single 'Itchycoo Park', plus 1968 No.1 UK album 'Ogden's Nut Gone Flake', Humble Pie, 1969 UK No.4 single 'Natural Born Bugie'. As a child actor he played parts in Dixon of Dock Green and The Artful Dodger in Oliver.

1992 - Freddie Mercury

'A Concert For Life' took place at Wembley Stadium as a tribute to Queen singer Freddie Mercury and for aids awareness. Acts appearing included; Elton John, Roger Daltrey, Tony Iommi (Black Sabbath), David Bowie, Mick Ronson, James Hetfield, George Michael, Seal, Paul Young, Annie Lennox, Lisa Stansfield, Robert Plant, Joe Elliott and Phil Collen, Axl Rose and Slash.

1993 - Aerosmith

Aerosmith released 'Get A Grip' their 11th studio album which became their best selling album to date with sales over 20m. The album which featured the hits: 'Livin' On The Edge' and 'Crazy' also featured guests Don Henley and Lenny Kravitz.

2001 - Peter Frampton

A memorial concert for former Small Faces and Humble Pie front man Steve Marriott took place at the London Astoria with Peter Frampton, Midge Ure, Chris Farlowe and Humble Pie.

2020 - Willie Nelson

Stuck at home in lockdown during the coronavirus pandemic, Willie Nelson staged the "Come And Toke It" live stream (in reference to 420 day, "the unofficial weed holiday"), to support efforts to legalize marijuana and free those incarcerated for it. Other guests included Ziggy Marley, Kacey Musgraves, Billy Ray Cyrus and Toby Keith.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stansfield Turner

#suitdaddy#suiteddaddy#suit and tie#men in suits#suited daddy#suited grandpa#suitedman#suit daddy#daddy#silverfox#suitfetish#buisness suit#suited men#suitedmen#suited man#americans#cia director#Carter administration#Stansfield Turner

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

The UK parliament’s Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee is working on its report (and recommendations) from its inquiry into the economics of music streaming. One of the big talking points during the inquiry’s evidence sessions was equitable remuneration (ER): specifically extending it from radio and TV to some streams.

The Broken Record campaign has made ER one of its key requests of the committee; labels have argued firmly against it; and (in our view, at least) the committee seems to be leaning more towards the former camp. But the committee isn’t the British government, so if ER is to be extended, ministers will need to be convinced too.

That campaign is already starting. A letter sent to Prime Minister Boris Johnson – and shown to Music Ally this morning – sees a who’s who of British musicians backing such an extension. Sir Paul McCartney, Annie Lennox, Chris Martin, Jimmy Page, Robert Plant, Kate Bush, Roger Daltrey, Damon Albarn, Noel Gallagher, Laura Marling, Sir Tim Rice… and many more.

“Only two words need to change in the 1988 Copyright, Designs and Patents Act. This will modernise the law so that today’s performers receive a share of revenues, just like they enjoy in radio,” argues the letter. But it also calls for a competition inquiry (or at least a government referral to watchdog the Competition and Markets Authority); for songwriters to get a bigger share of streaming royalties; and the establishment of a dedicated regulator “to ensure the lawful and fair treatment of music makers”.

Later today, we’ll publish our quarterly Music Ally report, including our analysis of the key talking points of the inquiry, and what might happen next. One of our suggestions was that while the DCMS committee seemed sympathetic to the Broken Record campaign’s arguments, the government ministers seemed to be leaning more towards labels’ view of the world.

The letter shows that the former group are going to work hard to change that, and in wheeling out the musical big guns, the intensity of the lobbying has stepped up several notches – even before the DCMS committee’s report has come out. Labels and their representative body the BPI must now decide how best to respond.

Here is the full text of the letter, and its signatories:

———-

Dear Prime Minister,

We write to you on behalf of today’s generation of artists, musicians and songwriters here in the UK.

For too long, streaming platforms, record labels and other internet giants have exploited performers and creators without rewarding them fairly. We must put the value of music back where it belongs – in the hands of music makers.

Streaming is quickly replacing radio as our main means of music communication. However, the law has not kept up with the pace of technological change and, as a result, performers and songwriters do not enjoy the same protections as they do in radio.

Today’s musicians receive very little income from their performances – most featured artists receive tiny fractions of a US cent per stream and session musicians receive nothing at all.

To remedy this, only two words need to change in the 1988 Copyright, Designs and Patents Act. This will modernise the law so that today’s performers receive a share of revenues, just like they enjoy in radio. It won’t cost the taxpayer a penny but will put more money in the pockets of UK taxpayers and raise revenues for public services like the NHS.

There is evidence of multinational corporations wielding extraordinary power and songwriters struggling as a result. An immediate government referral to the Competition and Markets Authority is the first step to address this. Songwriters earn 50% of radio revenues, but only 15% in streaming. We believe that in a truly free market the song will achieve greater value.

Ultimately though, we need a regulator to ensure the lawful and fair treatment of music makers. The UK has a proud history of protecting its producers, entrepreneurs and inventors. We believe British creators deserve the same protections as other industries whose work is devalued when exploited as a loss-leader.

By addressing these problems, we will make the UK the best place in the world to be a musician or a songwriter, allow recording studios and the UK session scene to thrive once again, strengthen our world leading cultural sector, allow the market for recorded music to flourish for listeners and creators, and unearth a new generation of talent.

We urge you to take these forward and ensure the music industry is part of your levelling-up agenda as we kickstart the post-Covid economic recovery.

Yours sincerely,

Full list of signatories:

Damon Albarn OBE

Lily Allen

Wolf Alice

Marc Almond OBE

Joan Armatrading CBE

David Arnold

Massive Attack

Jazzie B OBE

Adam Bainbridge (Kindness)

Emily Barker

Gary Barlow OBE

Geoff Barrow

Django Bates

Brian Bennett OBE

Fiona Bevan

Alfie Boe OBE

Billy Bragg

The Chemical Brothers

Kate Bush CBE

Melanie C

Eliza Carthy MBE

Martin Carthy MBE

Celeste

Guy Chambers

Mike Batt LVO

Don Black OBE

Badly Drawn Boy

Chrissy Boy

Tim Burgess

Mairéad Carlin

Laura-Mary Carter

Nicky Chinn

Dame Sarah Connolly DBE

Phil Coulter

Roger Daltrey CBE

Catherine Anne Davies (The Anchoress)

Ian Devaney

Chris Difford

Al Doyle

Anne Dudley

Brian Eno

Self Esteem

James Fagan

Paloma Faith

Marianne Faithfull

George Fenton

Rebecca Ferguson

Robert Fripp

Shy FX

Gabrielle

Peter Gabriel

Noel Gallagher

Guy Garvey

Bob Geldof KBE

Boy George

David Gilmour CBE

Nigel Godrich

Howard Goodall CBE

Jimi Goodwin

Graham Gouldman

Tom Gray

Roger Greenaway OBE

Will Gregory

Ed Harcourt

Tony Hatch OBE

Richard Hawley

Justin Hayward

Fran Healy

Orlando Higginbottom

Jools Holland OBE, DL

Mick Hucknall

Crispin Hunt

Shabaka Hutchings

Eric Idle

John Paul Jones

Julian Joseph OBE

Kano

Linton Kwesi Johnson

Gary Kemp

Nancy Kerr

Richard Kerr

Soweto Kinch

Beverley Knight MBE

Mark Knopfler OBE

Annie Lennox OBE

Shaznay Lewis

Gary Lightbody OBE

Tasmin Little OBE

Calum MacColl

Roots Manuva

Laura Marling

Johnny Marr

Chris Martin

Claire Martin OBE

Cerys Matthews MBE

Sir Paul McCartney CH MBE

Horse McDonald

Thurston Moore

Gary “Mani” Mounfield

Mitch Murray CBE

Field Music

Frank Musker

Laura Mvula

Kate Nash

Stevie Nicks

Orbital

Roland Orzabal

Gary Osborne

Jimmy Page OBE

Hannah Peel

Daniel Pemberton

Yannis Philippakis

Anna Phoebe

Phil Pickett

Robert Plant CBE

Karine Polwart

Emily Portman

Chris Rea

Eddi Reader MBE

Sir Tim Rice

Orphy Robinson MBE

Matthew Rose

Nitin Sawhney CBE

Anil Sebastian

Peggy Seeger

Nadine Shah

Feargal Sharkey OBE

Shura

Labi Siffre

Martin Simpson

Skin

Mike Skinner

Curt Smith

Fraser T Smith

Robert Smith

Sharleen Spiteri

Lisa Stansfield

Sting CBE

Suggs

Tony Swain

Heidi Talbot

John Taylor

Phil Thornalley

KT Tunstall

Ruby Turner MBE

Becky Unthank

Norma Waterson MBE

Cleveland Watkiss MBE

Jessie Ware

Bruce Welch OBE

Kitty Whately

Ricky Wilde

Olivia Williams

Daniel “Woody” Woodgate

Midge Ure OBE

Nikki Yeoh

1 note

·

View note

Note

oof i know you said not to ask you for music recs, but i legit just made a spotify a few days ago because i want in on all the playlists with extremely long names so could you maybe gimme some stuff please 👉👈?? (idk if this part is necessary but I like rock and the Very Specific genre that is love songs with religious imagery and, as to be expected, Gay Songs.)

I'm not sure what kind of rock music you're into, so I'll give you a good starter list of both hard rock/mellow metal and soft rock, as well as some good 80's rock and oldies alternative music.. as for love songs with religious imagery, I'm not sure if you're open to songs in languages other than English (most of my religious love songs are either Hozier or assorted Italian songs) but I do have a good amount of gay songs for you!! Sorry in advance for the hellstorm this list is going to be.

Without further ado:

For rock songs, we have..

20/20 by Crown The Empire

Adore by Numenorean

Adrenalize by In This Moment

Against The Wall by Seether(acoustic ver.)

Ain't No Rest For The Wicked by Cage The Elephant

All I Had To Lose by Mark Morton and Mark Morales

All My Friends by Creeper

All The Same by Sick Puppies

Angel by Theory of a Deadman

Angels Fall by Breaking Benjamin

Angel With a Shotgun by The Cab

Anger Left Behind by Atreyu

Another Life by Motionless in White

Ashes of Eden by Breaking Benjamin

Awake and Alive by Skillet

Bartzabel by Behemoth

Big Tings by Skindred

The Black by Asking Alexandria

Black Smoke Rising by Greta Van Fleet

Black Wedding by In This Moment

Bleeding In The Blur by Code Orange

Blind by Saint Asonia

Blood by Breaking Benjamin

Blood Eagle by Periphery

Bloodline by Inferious

Bloody by Five Finger Death Punch

Blue Lies by Year of The Knife

The Blue, The Green by Lonely The Brave

Blurry by Puddle of Mudd

Bother by Stone Sour

Bow Down by I Prevail

Breakdown by Tantric

Break In by Hailstorm

Breaking The Silence by Breaking Benjamin

Broken by Seether and Amy Lee (personal fav)

Burn it Down by Silverstein and Caleb Shomo

Burn it Down by Five Finger Death Punch

Bury Me Alive by Breaking Benjamin

California Dreaming by Hollywood Undead

Call Me by Shinedown

Carry The Weight by We Came As Romans

C'est La Vie by Protest The Hero

Choke by I DON'T KNOW HOW BUT THEY FOUND ME

Chop Suey! by System of a Down

Cirice by Ghost

Click Click Boom by Saliva

Close to Heaven by Breaking Benjamin

Cold Like War by We Came As Romans

Comatose by Skillet

Comedown by Bush

Crawl by Breaking Benjamin

Crawling in The Dark by Hoobastank

Cross Off by Mark Morton and Chester Bennington

Cry Little Sister by Seasons After

Cut the Cord by Shinedown

Cutthroat by blessthefall

Dance Macabre by Ghost

Dark by Breaking Benjamin

Darlin' by Goodbye June

Dawn by Breaking Benjamin

A Day in My Life by Five Finger Death Punch

Dear Agony - Aurora Ver. by Breaking Benjamin and Lacey Sturm

Deathbox by Mnemic

Defeated by Breaking Benjamin

Demon Rat by BackWordz

Demons Are A Girl's Best Friend by Powerwolf

DEVIL by Shinedown

The Devil's Bleeding Crown by Volbeat

The Diary of Jane by Breaking Benjamin

Dignity by Opeth

Disarm-Remastered by The Smashing Pumpkins

Don't Need You - Edit by Bullet For My Valentine

Don't Tell Me What To Dream by God Forbid

I think that should be good.. this post is getting super duper long so let's move on to love songs..

Angel of Small Death and the Codeine Scene by Hozier

Beige by Yoke Lore

Come Sono by Albert

End of Time by Johnny Stimson and Gisel

Foreigners God by Hozier

From Eden by Hozier

A few of the rock songs above have religious themes, so those can technically fit this section too

Finally, gay songs!

Suddenly I See by KT Tunstall

Secret by Chelsea Lankes

I Think She Knows by Kaki King

Sick of Losing Soulmates by dodie

Night Go Slow by Catie Shaw

I Was an Island by Allison Weiss

She by Jen Foster

Explosion by Zolita

She Keeps Me Warm by Mary Lambert

Sleepover by Hayley Kiyoko

Jenny by Studio Killers

Girls Like Girls by Hayley Kiyoko

strangers by lovelytheband

If I'm Being Honest by dodie

Human by dodie

In The Middle by dodie

In My Dreams by Ruth B.

Rhythm of Love by Plain White T's

I'm The Only One by Melissa Etheridge

Pink Lemonade by The Wombats

Shimmer by Fuel

She by dodie

Why by Annie Lennox

Get Here by Oleta Adams

That's What Love is For by Amy Grant

All Woman by Lisa Stansfield

Save The Best For Last by Vanessa Williams

Someone Else's Eyes by Aretha Franklin

Happy Ever After by Julia Fordham

Dance Without Sleeping by Melissa Etheridge

All I Wanna Do by Sheryl Crow

Coming Around Again by Carly Simon

Walking Away A Winner by Kathy Mattea

I'll Be Your Shelter by Taylor Dayne

The Best by Tina Turner

Only A Girl by Gia Woods

Pretty Girl by Hayley Kiyoko

Tea For Two by Pink Martini

Radiant Warmth by Miki Ratsula

July by HUNNY

Heart Break by Brittany Brannock (I love her so much you have no idea)

That should be plenty to get you started! Hope you like the lists!

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Complaints of a CIA agent

Here is my answer:

If your concern involves a program or operation administered by U.S. Government department or agency, please submit your concern directly to that agency.

- Stansfield Turner

0 notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://www.stl.news/stansfield-turner-who-led-major-cia-reforms-dies/69985/

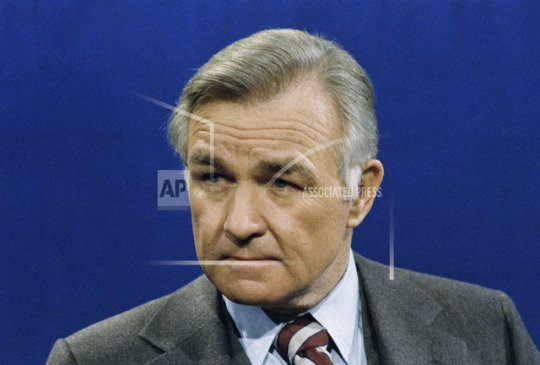

Stansfield Turner, who led major CIA reforms, dies

SEATTLE/January 18, 2018 (AP)(STL.News) —Stansfield A. Turner, who served as CIA director under President Jimmy Carter and oversaw reforms at the agency after the Senate uncovered CIA surveillance aimed at American citizens, has died. He was 94.

Turner’s secretary, Pat Moynihan, confirmed to the Washington Post that Turner died on Thursday at his home in Seattle but Moynihan did not disclose the cause.

A Rhodes scholar and 33-year Navy veteran, Turner commanded NATO’s forces in southern Europe from 1975 to 1977 before being chosen to direct the Central Intelligence Agency.

Turner headed the agency from March 1977, shortly after Carter took office, through the end of Carter’s term in January 1981.

Turner promised at his Senate confirmation hearing to conduct intelligence operations “strictly in accordance with the law and American values.” He also said “covert operations must be handled very discreetly. People’s lives are at stake.”

A day later, the Senate unanimously confirmed his appointment.

As in recent years, questions of how to structure and oversee the nation’s vast military and civilian intelligence operations were a big issue in the 1970s.

The investigation of the CIA in 1975 and ’76 by the Senate committee headed by Sen. Frank Church had exposed CIA assassination plots, including the hiring of Mafia hit men in a failed bid to kill Fidel Castro, as well as CIA surveillance aimed at American citizens.

When Turner was chosen as CIA director in early 1977, New York Times columnist Tom Wicker wrote that “he’s got a bear by the tail, one that even the most bold and determined director probably can’t control.”

Turner was the first director given full authority over the agency’s $7 billion budget. Assassinations and medical experiments on unwitting human subjects were prohibited. But he argued that some proposals aimed at sharing agency information with Congress went too far, because some operations were too sensitive and the possibility of damaging leaks too great.

Among the events occurring during Turner’s term was the Iranian hostage crisis of 1979-81 and the disastrous U.S. attempt to rescue the hostages in April 1980 that left eight U.S. servicemen dead.

In 1982, the by-then-former CIA chief Turner told The Washington Post that the rescue mission should be investigated, “not to look backward and cast blame but to look forward and learn the lessons that surely lie buried in (it.)”

After leaving the CIA, Turner’s positions frequently put him at odds with Carter’s successor, President Ronald Reagan. In 1987, Turner told reporters Reagan had to have known about the diversion of Iranian arms sale proceeds to Nicaraguan rebels at a time when Reagan said he had no knowledge of the plan.

In his 1985 book, “Secrecy and Democracy,” Turner said the CIA under the Reagan presidency had violated the law in failing to notify Congress of covert operations “in a timely manner.”

“Our ethical standards in dealing with our Central American neighbors were revealed as not what we would like to believe them to be,” Turner wrote. “The world saw that we had endangered the lives and property of countries not involved with the dispute between us and Nicaragua, and that we were deliberately interfering in the affairs of Nicaragua to the point of undeclared war.”

When President George W. Bush revamped intelligence in 2005, naming a national intelligence director with oversight over all operations, Turner argued for a more radical overhaul that would combine all intelligence-gathering under one roof, separate from the analytical function.

Each information-gathering agency, he said in an Oct. 6, 2005, speech, tends to value its own intelligence findings ahead of all others. Constant “tweaking” of the spy agencies’ functions and structure by successive administrations “has not left us today with a coherent intelligence structure,” he said.

In the post-Cold War years, Turner also was a strong advocate for nuclear disarmament. In his 1997 book “Caging the Nuclear Genie — An American Challenge for Global Security,” Turner propounded the concept of “strategic escrow” — effectively mothballing hundreds of nuclear missiles by storing them hundreds of miles from any launch site and allowing Russian observers to keep track of their movements.

The hope was with that gesture, the Russians would reciprocate and mothball a number of its own warheads.

Turner maintained that even if the Russians didn’t reduce their arsenal, the United States would still have enough nuclear weapons to retaliate with deadly force if ever needed.

Born in Highland Park, Illinois in 1923, Turner was an author, professor and corporate director.

Turner was in the same 1947 naval class at Annapolis as Jimmy Carter, but the men didn’t know each other. Turner finished 25th in the class of 820 cadets while the future president finished 59th.

After serving in both the Korean and Vietnam wars, Turner was appointed president of the Naval War College at Newport, Rhode Island in 1972. He was promoted to the rank of admiral and became commander of NATO’s southern European forces in 1975.

Turner praised his old boss in 2005 at the ceremony when the huge submarine USS Jimmy Carter officially entered the Navy’s fleet.

He said Carter was a model as “an effective president while also showing the world what the United States stands for in values, in integrity, in morality, in unselfish compassion for others, in the pursuit of peace.”

In addition to his writings and speeches, Turner taught in recent years at the University of Maryland’s School of Public Policy.

Turner’s first marriage to Patricia Busby Whitney ended in divorce in 1984. They had two children, Laurel and Geoffrey. Turner married Eli Karin Gilbert in 1985. She and three other passengers were killed in 2000 in a Costa Rica plane crash in which Turner was seriously injured. In 2002, he married Marion Levitt Weiss.

___

by Associated Press – published on STL.News by St. Louis Media, LLC (Z.S)

___

0 notes

Text

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/music-black-culture-appropriation.html

I'd encourage all of you to read -- actually read -- the reported essays in the #1619project. If these ideas or facts are new to you, if they upset you or make you uncomfortable, if they challenge your idea of America, ask yourself: why?

For centuries, black music, forged in bondage, has been the sound of complete artistic freedom. No wonder everybody is always stealing it.

By Wesley Morris | August 14, 2019 | New York Times | Posted August 18, 2019 7:52 PM ET |

I’ve got a friend who’s an incurable Pandora guy, and one Saturday while we were making dinner, he found a station called Yacht Rock. “A tongue-in-cheek name for the breezy sounds of late ’70s/early ’80s soft rock” is Pandora’s definition, accompanied by an exhortation to “put on your Dockers, pull up a deck chair and relax.” With a single exception, the passengers aboard the yacht were all dudes. With two exceptions, they were all white. But as the hours passed and dozens of songs accrued, the sound gravitated toward a familiar quality that I couldn’t give language to but could practically taste: an earnest Christian yearning that would reach, for a moment, into Baptist rawness, into a known warmth. I had to laugh — not because as a category Yacht Rock is absurd, but because what I tasted in that absurdity was black.

I started putting each track under investigation. Which artists would saunter up to the racial border? And which could do their sauntering without violating it? I could hear degrees of blackness in the choir-loft certitude of Doobie Brothers-era Michael McDonald on “What a Fool Believes”; in the rubber-band soul of Steely Dan’s “Do It Again”; in the malt-liquor misery of Ace’s “How Long” and the toy-boat wistfulness of Little River Band’s “Reminiscing.”

Then Kenny Loggins’s “This Is It”arrived and took things far beyond the line. “This Is It” was a hit in 1979 and has the requisite smoothness to keep the yacht rocking. But Loggins delivers the lyrics in a desperate stage whisper, like someone determined to make the kind of love that doesn’t wake the baby. What bowls you over is the intensity of his yearning — teary in the verses, snarling during the chorus. He sounds as if he’s baring it all yet begging to wring himself out even more.

Playing black-music detective that day, I laughed out of bafflement and embarrassment and exhilaration. It’s the conflation of pride and chagrin I’ve always felt anytime a white person inhabits blackness with gusto. It’s: You have to hand it to her. It’s: Go, white boy. Go, white boy. Go. But it’s also: Here we go again. The problem is rich. If blackness can draw all of this ornate literariness out of Steely Dan and all this psychotic origami out of Eminem; if it can make Teena Marie sing everything — “Square Biz,” “Revolution,”“Portuguese Love,” “Lovergirl” — like she knows her way around a pack of Newports; if it can turn the chorus of Carly Simon’s “You Belong to Me” into a gospel hymn; if it can animate the swagger in the sardonic vulnerabilities of Amy Winehouse; if it can surface as unexpectedly as it does in the angelic angst of a singer as seemingly green as Ben Platt; if it’s the reason Nu Shooz’s “I Can’t Wait”remains the whitest jam at the blackest parties, then it’s proof of how deeply it matters to the music of being alive in America, alive to America.

It’s proof, too, that American music has been fated to thrive in an elaborate tangle almost from the beginning. Americans have made a political investment in a myth of racial separateness, the idea that art forms can be either “white” or “black” in character when aspects of many are at least both. The purity that separation struggles to maintain? This country’s music is an advertisement for 400 years of the opposite: centuries of “amalgamation” and “miscegenation” as they long ago called it, of all manner of interracial collaboration conducted with dismaying ranges of consent.

“White,” “Western,” “classical” music is the overarching basis for lots of American pop songs. Chromatic-chord harmony, clean timbre of voice and instrument: These are the ingredients for some of the hugely singable harmonies of the Beatles, the Eagles, Simon and Fleetwood Mac, something choral, “pure,” largely ungrained. Black music is a completely different story. It brims with call and response, layers of syncopation and this rougher element called “noise,” unique sounds that arise from the particular hue and timbre of an instrument — Little Richard’s woos and knuckled keyboard zooms. The dusky heat of Miles Davis’s trumpeting. Patti LaBelle’s emotional police siren. DMX’s scorched-earth bark. The visceral stank of Etta James, Aretha Franklin, live-in-concert Whitney Houston and Prince on electric guitar.

But there’s something even more fundamental, too. My friend Delvyn Case, a musician who teaches at Wheaton College, explained in an email that improvisation is one of the most crucial elements in what we think of as black music: “The raising of individual creativity/expression to the highest place within the aesthetic world of a song.” Without improvisation, a listener is seduced into the composition of the song itself and not the distorting or deviating elements that noise creates. Particular to black American music is the architecture to create a means by which singers and musicians can be completely free, free in the only way that would have been possible on a plantation: through art, through music — music no one “composed” (because enslaved people were denied literacy), music born of feeling, of play, of exhaustion, of hope.

What you’re hearing in black music is a miracle of sound, an experience that can really happen only once — not just melisma, glissandi, the rasp of a sax, breakbeats or sampling but the mood or inspiration from which those moments arise. The attempt to rerecord it seems, if you think about it, like a fool’s errand. You’re not capturing the arrangement of notes, per se. You’re catching the spirit.

And the spirit travels from host to host, racially indiscriminate about where it settles, selective only about who can withstand being possessed by it. The rockin’ backwoods blues so bewitched Elvis Presley that he believed he’d been called by blackness. Chuck Berry sculpted rock ’n’ roll with uproarious guitar riffs and lascivious winks at whiteness. Mick Jagger and Robert Plant and Steve Winwood and Janis Joplin and the Beatles jumped, jived and wailed the black blues. Tina Turner wrested it all back, tripling the octane in some of their songs. Since the 1830s, the historian Ann Douglas writes in “Terrible Honesty,” her history of popular culture in the 1920s, “American entertainment, whatever the state of American society, has always been integrated, if only by theft and parody.” What we’ve been dealing with ever since is more than a catchall word like “appropriation” can approximate. The truth is more bounteous and more spiritual than that, more confused. That confusion is the DNA of the American sound.

It’s in the wink-wink costume funk of Beck’s “Midnite Vultures” from 1999, an album whose kicky nonsense deprecations circle back to the popular culture of 150 years earlier. It’s in the dead-serious, nostalgic dance-floor schmaltz of Bruno Mars. It’s in what we once called “blue-eyed soul,” a term I’ve never known what to do with, because its most convincing practitioners — the Bee-Gees, Michael McDonald, Hall & Oates, Simply Red, George Michael, Taylor Dayne, Lisa Stansfield, Adele — never winked at black people, so black people rarely batted an eyelash. Flaws and all, these are homeowners as opposed to renters. No matter what, though, a kind of gentrification tends to set in, underscoring that black people have often been rendered unnecessary to attempt blackness. Take Billboard’s Top 10 songs of 2013: It’s mostly nonblack artists strongly identified with black music, for real and for kicks: Robin Thicke, Miley Cyrus, Justin Timberlake, Macklemore and Ryan Lewis, the dude who made “The Harlem Shake.”

Sometimes all the inexorable mixing leaves me longing for something with roots that no one can rip all the way out. This is to say that when we’re talking about black music, we’re talking about horns, drums, keyboards and guitars doing the unthinkable together. We’re also talking about what the borrowers and collaborators don’t want to or can’t lift — centuries of weight, of atrocity we’ve never sufficiently worked through, the blackness you know is beyond theft because it’s too real, too rich, too heavy to steal.

Blackness was on the move before my ancestors were legally free to be. It was on the move before my ancestors even knew what they had. It was on the move because white people were moving it. And the white person most frequently identified as its prime mover is Thomas Dartmouth Rice, a New Yorker who performed as T.D. Rice and, in acclaim, was lusted after as “Daddy” Rice, “the negro par excellence.” Rice was a minstrel, which by the 1830s, when his stardom was at its most refulgent, meant he painted his face with burned cork to approximate those of the enslaved black people he was imitating.

In 1830, Rice was a nobody actor in his early 20s, touring with a theater company in Cincinnati (or Louisville; historians don’t know for sure), when, the story goes, he saw a decrepit, possibly disfigured old black man singing while grooming a horse on the property of a white man whose last name was Crow. On went the light bulb. Rice took in the tune and the movements but failed, it seems, to take down the old man’s name. So in his song based on the horse groomer, he renamed him: “Weel about and turn about jus so/Ebery time I weel about, I jump Jim Crow.” And just like that, Rice had invented the fellow who would become the mascot for two centuries of legalized racism.

That night, Rice made himself up to look like the old black man — or something like him, because Rice’s get-up most likely concocted skin blacker than any actual black person’s and a gibberish dialect meant to imply black speech. Rice had turned the old man’s melody and hobbled movements into a song-and-dance routine that no white audience had ever experienced before. What they saw caused a permanent sensation. He reportedly won 20 encores.

Rice repeated the act again, night after night, for audiences so profoundly rocked that he was frequently mobbed duringperformances. Across the Ohio River, not an arduous distance from all that adulation, was Boone County, Ky., whose population would have been largely enslaved Africans. As they were being worked, sometimes to death, white people, desperate with anticipation, were paying to see them depicted at play.

[To get updates on The 1619 Project, and for more on race from The New York Times, sign up for our weekly Race/Related newsletter.]

Other performers came and conquered, particularly the Virginia Minstrels, who exploded in 1843, burned brightly then burned out after only months. In their wake, P.T. Barnum made a habit of booking other troupes for his American Museum; when he was short on performers, he blacked up himself. By the 1840s, minstrel acts were taking over concert halls, doing wildly clamored-for residencies in Boston, New York and Philadelphia.

A blackface minstrel would sing, dance, play music, give speeches and cut up for white audiences, almost exclusively in the North, at least initially. Blackface was used for mock operas and political monologues (they called them stump speeches), skits, gender parodies and dances. Before the minstrel show gave it a reliable home, blackface was the entertainment between acts of conventional plays. Its stars were the Elvis, the Beatles, the ’NSync of the 19th century. The performers were beloved and so, especially, were their songs.

During minstrelsy’s heyday, white songwriters like Stephen Foster wrote the tunes that minstrels sang, tunes we continue to sing. Edwin Pearce Christy’s group the Christy Minstrels formed a band — banjo, fiddle, bone castanets, tambourine — that would lay the groundwork for American popular music, from bluegrass to Motown. Some of these instruments had come from Africa; on a plantation, the banjo’s body would have been a desiccated gourd. In “Doo-Dah!” his book on Foster’s work and life, Ken Emerson writes that the fiddle and banjo were paired for the melody, while the bones “chattered” and the tambourine “thumped and jingled a beat that is still heard ’round the world.”

But the sounds made with these instruments could be only imagined as black, because the first wave of minstrels were Northerners who’d never been meaningfully South. They played Irish melodies and used Western choral harmonies, not the proto-gospel call-and-response music that would make life on a plantation that much more bearable. Black artists were on the scene, like the pioneer bandleader Frank Johnsonand the borderline-mythical Old Corn Meal, who started as a street vendor and wound up the first black man to perform, as himself, on a white New Orleans stage. His stuff was copied by George Nichols, who took up blackface after a start in plain-old clowning. Yet as often as not, blackface minstrelsy tethered black people and black life to white musical structures, like the polka, which was having a moment in 1848. The mixing was already well underway: Europe plus slavery plus the circus, times harmony, comedy and drama, equals Americana.

And the muses for so many of the songs were enslaved Americans, people the songwriters had never met, whose enslavement they rarely opposed and instead sentimentalized. Foster’s minstrel-show staple “Old Uncle Ned,” for instance, warmly if disrespectfully eulogizes the enslaved the way you might a salaried worker or an uncle:

Den lay down de shubble and de hoe,

Hang up de fiddle and de bow:

No more hard work for poor Old Ned —

He’s gone whar de good Niggas go,

No more hard work for poor Old Ned —

He’s gone whar de good Niggas go.

Such an affectionate showcase for poor old (enslaved, soon-to-be-dead) Uncle Ned was as essential as “air,” in the white critic Bayard Taylor’s 1850 assessment; songs like this were the “true expressions of the more popular side of the national character,” a force that follows “the American in all its emigrations, colonizations and conquests, as certainly as the Fourth of July and Thanksgiving Day.” He’s not wrong. Minstrelsy’s peak stretched from the 1840s to the 1870s, years when the country was as its most violently and legislatively ambivalent about slavery and Negroes; years that included the Civil War and Reconstruction, the ferocious rhetorical ascent of Frederick Douglass, John Brown’s botched instigation of a black insurrection at Harpers Ferry and the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

Minstrelsy’s ascent also coincided with the publication, in 1852, of “Uncle Tom's Cabin,” a polarizing landmark that minstrels adapted for the stage, arguing for and, in simply remaining faithful to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel, against slavery. These adaptations, known as U.T.C.s, took over the art form until the end of the Civil War. Perhaps minstrelsy’s popularity could be (generously) read as the urge to escape a reckoning. But a good time predicated upon the presentation of other humans as stupid, docile, dangerous with lust and enamored of their bondage? It was an escape into slavery’s fun house.

What blackface minstrelsy gave the country during this period was an entertainment of skill, ribaldry and polemics. But it also lent racism a stage upon which existential fear could become jubilation, contempt could become fantasy. Paradoxically, its dehumanizing bent let white audiences feel more human. They could experience loathing as desire, contempt as adoration, repulsion as lust. They could weep for overworked Uncle Ned as surely as they could ignore his lashed back or his body as it swung from a tree.

But where did this leave a black performer? If blackface was the country’s cultural juggernaut, who would pay Negroes money to perform as themselves? When they were hired, it was only in a pinch. Once, P.T. Barnum needed a replacement for John Diamond, his star white minstrel. In a New York City dance hall, Barnum found a boy, who, it was reported at the time, could outdo Diamond (and Diamond was good). The boy, of course, was genuinely black. And his being actually black would have rendered him an outrageous blight on a white consumer’s narrow presumptions. As Thomas Low Nichols would write in his 1864 compendium, “Forty Years of American Life,” “There was not an audience in America that would not have resented, in a very energetic fashion, the insult of being asked to look at the dancing of a real negro.” So Barnum “greased the little ‘nigger’s’ face and rubbed it over with a new blacking of burned cork, painted his thick lips vermilion, put on a woolly wig over his tight curled locks and brought him out as ‘the champion nigger-dancer of the world.’ ” This child might have been William Henry Lane, whose stage name was Juba. And, as Juba, Lane was persuasive enough that Barnum could pass him off as a white person in blackface. He ceased being a real black boy in order to become Barnum’s minstrel Pinocchio.

After the Civil War, black performers had taken up minstrelsy, too, corking themselves, for both white and black audiences — with a straight face or a wink, depending on who was looking. Black troupes invented important new dances with blue-ribbon names (the buck-and-wing, the Virginia essence, the stop-time). But these were unhappy innovations. Custom obligated black performers to fulfill an audience’s expectations, expectations that white performers had established. A black minstrel was impersonating the impersonation of himself. Think, for a moment, about the talent required to pull that off. According to Henry T. Sampson’s book, “Blacks in Blackface,” there were no sets or effects, so the black blackface minstrel show was “a developer of ability because the artist was placed on his own.” How’s that for being twice as good? Yet that no-frills excellence could curdle into an entirely other, utterly degrading double consciousness, one that predates, predicts and probably informs W.E.B. DuBois’s more self-consciously dignified rendering.

American popular culture was doomed to cycles not only of questioned ownership, challenged authenticity, dubious propriety and legitimate cultural self-preservation but also to the prison of black respectability, which, with brutal irony, could itself entail a kind of appropriation. It meant comportment in a manner that seemed less black and more white. It meant the appearance of refinement and polish. It meant the cognitive dissonance of, say, Nat King Cole’s being very black and sounding — to white America, anyway, with his frictionless baritone and diction as crisp as a hospital corner — suitably white. He was perfect for radio, yet when he got a TV show of his own, it was abruptly canceled, his brown skin being too much for even the black and white of a 1955 television set. There was, perhaps, not a white audience in America, particularly in the South, that would not have resented, in a very energetic fashion, the insult of being asked to look at the majestic singing of a real Negro.

The modern conundrum of the black performer’s seeming respectable, among black people, began, in part, as a problem of white blackface minstrels’ disrespectful blackness. Frederick Douglass wrote that they were “the filthy scum of white society.” It’s that scum that’s given us pause over everybody from Bert Williams and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson to Flavor Flav and Kanye West. Is their blackness an act? Is the act under white control? Just this year, Harold E. Doley Jr., an affluent black Republican in his 70s, was quoted in The Times lamenting West and his alignment with Donald Trump as a “bad and embarrassing minstrel show” that “served to only drive black people away from the G.O.P.”

But it’s from that scum that a robust, post-minstrel black American theater sprung as a new, black audience hungered for actual, uncorked black people. Without that scum, I’m not sure we get an event as shatteringly epochal as the reign of Motown Records. Motown was a full-scale integration of Western, classical orchestral ideas (strings, horns, woodwinds) with the instincts of both the black church (rhythm sections, gospel harmonies, hand claps) and juke joint Saturday nights (rhythm sections, guitars, vigor). Pure yet “noisy.” Black men in Armani. Black women in ball gowns. Stables of black writers, producers and musicians. Backup singers solving social equations with geometric choreography. And just in time for the hegemony of the American teenager.

Even now it feels like an assault on the music made a hundred years before it. Motown specialized in love songs. But its stars, those songs and their performance of them were declarations of war on the insults of the past and present. The scratchy piccolo at the start of a Four Tops hitwas, in its way, a raised fist. Respectability wasn’t a problem with Motown; respectability was its point. How radically optimistic a feat of antiminstrelsy, for it’s as glamorous a blackness as this country has ever mass-produced and devoured.

The proliferation of black music across the planet — the proliferation, in so many senses, of being black — constitutes a magnificent joke on American racism. It also confirms the attraction that someone like Rice had to that black man grooming the horse. But something about that desire warps and perverts its source, lampoons and cheapens it even in adoration. Loving black culture has never meant loving black people, too. Loving black culture risks loving the life out of it.

And yet doesn’t that attraction make sense? This is the music of a people who have survived, who not only won't stop but also can’t be stopped. Music by a people whose major innovations — jazz, funk, hip-hop — have been about progress, about the future, about getting as far away from nostalgia as time will allow, music that’s thought deeply about the allure of outer space and robotics, music whose promise and possibility, whose rawness, humor and carnality call out to everybody — to other black people, to kids in working class England and middle-class Indonesia. If freedom's ringing, who on Earth wouldn't also want to rock the bell?

In 1845, J.K. Kennard, a critic for the newspaper The Knickerbocker, hyperventilated about the blackening of America. Except he was talking about blackface minstrels doing the blackening. Nonetheless, Kennard could see things for what they were:

“Who are our true rulers? The negro poets, to be sure! Do they not set the fashion, and give laws to the public taste? Let one of them, in the swamps of Carolina, compose a new song, and it no sooner reaches the ear of a white amateur, than it is written down, amended, (that is, almost spoilt,) printed, and then put upon a course of rapid dissemination, to cease only with the utmost bounds of Anglo-Saxondom, perhaps of the world.”

What a panicked clairvoyant! The fear of black culture — or “black culture” — was more than a fear of black people themselves. It was an anxiety over white obsolescence. Kennard’s anxiety over black influence sounds as ambivalent as Lorde’s, when, all the way from her native New Zealand, she tsk-ed rap culture’s extravagance on “Royals,”her hit from 2013, while recognizing, both in the song’s hip-hop production and its appetite for a particular sort of blackness, that maybe she’s too far gone:

Every song’s like gold teeth, Grey Goose, trippin’ in the bathroom

Bloodstains, ball gowns, trashin’ the hotel room

We don’t care, we’re driving Cadillacs in our dreams

But everybody’s like Cristal, Maybach, diamonds on your timepiece

Jet planes, islands, tigers on a gold leash

We don’t care, we aren’t caught up in your love affair

Beneath Kennard’s warnings must have lurked an awareness that his white brethren had already fallen under this spell of blackness, that nothing would stop its spread to teenage girls in 21st-century Auckland, that the men who “infest our promenades and our concert halls like a colony of beetles” (as a contemporary of Kennard’s put it) weren’t black people at all but white people just like him — beetles and, eventually, Beatles. Our first most original art form arose from our original sin, and some white people have always been worried that the primacy of black music would be a kind of karmic punishment for that sin. The work has been to free this country from paranoia’s bondage, to truly embrace the amplitude of integration. I don’t know how we’re doing.

Last spring, “Old Town Road,” a silly, drowsy ditty by the Atlanta songwriter Lil Nas X, was essentially banished from country radio. Lil Nas sounds black, as does the trap beat he’s droning over. But there’s definitely a twang to him that goes with the opening bars of faint banjo and Lil Nas’s lil’ cowboy fantasy. The song snowballed into a phenomenon. All kinds of people — cops, soldiers, dozens of dapper black promgoers — posted dances to it on YouTube and TikTok. Then a crazy thing happened. It charted — not just on Billboard’s Hot 100 singles chart, either. In April, it showed up on both its Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart and its Hot Country Songs chart. A first. And, for now at least, a last.

The gatekeepers of country radio refused to play the song; they didn’t explain why. Then, Billboard determined that the song failed to “embrace enough elements of today’s country music to chart in its current version.” This doesn’t warrant translation, but let’s be thorough, anyway: The song is too black for certain white people.

But by that point it had already captured the nation’s imagination and tapped into the confused thrill of integrated culture. A black kid hadn’t really merged white music with black, he’d just taken up the American birthright of cultural synthesis. The mixing feels historical. Here, for instance, in the song’s sample of a Nine Inch Nails track is a banjo, the musical spine of the minstrel era. Perhaps Lil Nas was too American. Other country artists of the genre seemed to sense this. White singers recorded pretty tributes in support, and one, Billy Ray Cyrus, performed his on a remix with Lil Nas X himself.

The newer version lays Cyrus’s casual grit alongside Lil Nas’s lackadaisical wonder. It’s been No.1 on Billboard’s all-genre Hot 100 singles chart since April, setting a record. And the bottomless glee over the whole thing makes me laugh, too — not in a surprised, yacht-rock way but as proof of what a fine mess this place is. One person's sign of progress remains another’s symbol of encroachment. Screw the history. Get off my land.

Four hundred years ago, more than 20 kidnapped Africans arrived in Virginia. They were put to work and put through hell. Twenty became millions, and some of those people found — somehow — deliverance in the power of music. Lil Nas X has descended from those millions and appears to be a believer in deliverance. The verses of his song flirt with Western kitsch, what young black internetters branded, with adorable idiosyncrasy and a deep sense of history, the “yee-haw agenda.” But once the song reaches its chorus (“I’m gonna take my horse to the Old Town Road, and ride til I can’t no more”), I don’t hear a kid in an outfit. I hear a cry of ancestry. He’s a westward-bound refugee; he’s an Exoduster. And Cyrus is down for the ride. Musically, they both know: This land is their land.

Wesley Morris is a staff writer for the magazine, a critic at large for The New York Times and a co-host of the podcast “Still Processing.” He was awarded the 2012 Pulitzer Prize for criticism.

Source photograph of Beyoncé: Kevin Mazur/Getty Images; Holiday: Paul Hoeffler/Redferns, via Getty Images; Turner: Gai Terrell/Redferns, via Getty Images; Richards: Chris Walter/WireImage, via Getty Images; Lamar: Bennett Raglin/Getty Images

#archives#music#must reads#african american history#american history#history#arts and entertainment#entertainment#entertainers#news#latest news#trending news#hip hop news source#1619#1619project

1 note

·

View note