#acomas

Text

Frog Drum

Joe Seymour Jr

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

Girl, you are pregnant

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Camas Flower Drum

Joe Wahalatsu? Seymour, Jr (Squaxin/Acoma Pueblo)

deer hide, maple frame, acrylic paint. 17.38” x 17.38” x 3”

#joe seymour jr#wahalatsu?#squaxin#acoma pueblo#drums#instruments#native art#first nations art#indigenous art

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mission church at McCartys, Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico

Photographer: John Candelario

Date: 1940 - 1950?

Negative Number: 165882

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

Acoma Pueblo potters (New Mexico)

The World of the American Indian, National Geographic, 1974

#indigenous art#indigenous#indigenas#indigenous history#acoma pueblo#ceramics#native art#indigenous artists#folk art#New Mexico#pueblo#vintage#nat geo

97 notes

·

View notes

Link

Excerpt from this story from Inside Climate News:

As a young girl, Arlene Juanico would rush to gather the laundry before the explosions started.

When the alarms sounded, Juanico would hustle to grab the clean garments off the clothesline before she was enveloped by dust clouds. But Juanico’s little legs usually couldn’t get her back to shelter in time.

That’s when the yellow-flecked dust—emerging from detonations in the sacred mesa the Laguna tribe knows as Squirrel Mountain—would catch up to her. That’s when it would enter Juanico’s throat, burrowing deep into her lungs.

It’s the same dust she would confront when, as an adult, she worked for the Anaconda Copper Co.

And it’s the dust that would persist in her lungs, kidneys and bones. There, hidden in the dark recesses of her chest, the particles lay until one day decades later a CT scan would show Juanico and people like her why they hadn’t been able to take a full breath in decades. They’d get a similar diagnosis—idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis—one mangled lung at a time.

As such, the dangers of one of the largest uranium mines in American history didn’t abate when the dust clouds dissipated.

Today, hundreds of mines lie abandoned across New Mexico’s Indigenous lands. So do scores of eroding radioactive landfills meant to bury uranium mine waste.

As a result, when the coronavirus struck in 2020, the Laguna—already afflicted by diseases that made it hard to walk, speak or breathe—were set up for severe Covid, said Loretta Anderson, a home health aide who is Laguna. So many of her people succumbed during the pandemic that the tribe enlarged its graveyard.

Federal guidance and state data suggest the same is true for thousands of Navajo and Acoma who were exposed to uranium before suffering life-threatening cases of Covid.

Now, these communities fear what the future holds for their wellbeing, health and culture.

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shooting the annular eclipse at the Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico was, without a doubt, the most profound and difficult photographic challenge and experience I had ever encountered. The Acoma Pueblo, perched atop its mystical mesa, held an allure like no other place. The sacredness of this ancient site beckoned me to capture an image that was not just aesthetically stunning but culturally significant. It is the longest continuously inhabited community in North America.

Obtaining permission to shoot on the mesa had been a herculean task in itself. The elders of the Acoma Tribe are understandably protective of their sacred grounds. It isn't a place where you just walk up and shoot. I had sent emails, made phone calls and left messages weeks ahead of time and it wasn't until a mere 15 minutes before the start of eclipse was to grace the sky, that a young member of the tribe, Jonah Chino, who worked with the dancers came through and granted their blessing and took her niece Ky'Mya Vallo and I up the mesa. The anticipation and tension in the air were palpable as I truly thought it was not going to happen.

As I lifted up my camera to shoot, a sense of gratitude washed over me, knowing that I had been entrusted with this incredible opportunity. I wasn't alone in this endeavor; I was working closely with the Sky City Buffalo Dancers from the Acoma Tribe and their leader Shane Keene. Their presence was like a bridge between the ancient traditions and the modern lens. Their rhythmic dances and ancient chants seemed to synchronize with the celestial ballet about to unfold.

The moments leading up to the eclipse were surreal, with a profound stillness in the air. As the moon began its graceful dance in front of the sun, I knew that the images I sought were not only the result of luck and passion but also the cooperation of the beautiful Acoma People. They had shared their sacred space and their heritage with me, allowing my lens to capture a moment where ancient wisdom and cosmic wonder intertwined.

In the poetic parlance, the female dancer in the Acoma traditional dance assumes a role of profound significance. They, the daughters of the earth, embody the very essence of fertility and motherhood. In their choreographic offerings, they grace the world with elegance and fluidity, their vibrant costumes adorned with the feathers, the tinkling of bells, and the visages of animal spirits.

Yet beyond this, their celestial charge extends to the Butterfly Dance. A ritual of healing, it beseeches the ethereal realm to mend the souls. Arrayed in butterfly wings and traditional garb, they exhibit the choreography of grace incarnate, invoking the tender spirits of the butterflies to mend the suffering soul.

Their function, however, transcends the earth. These female dancers ascend to a spiritual station of utmost importance. They serve as conduits to the unseen, incarnating spirits, their dances, a cryptic tongue for communion with the ethereal domain.

The resulting images were more than just photographs; they were a testament to the harmonious coexistence of tradition, nature, and modern artistry. They tell a story of unity, where the past met the present, and the eclipse became a bridge connecting cultures, generations, and the awe of the cosmos. I feel very blessed to have been there. Also, I was very blessed to be there with my lovely wife Hollee.

The diffuculty was due to the extreme differences in exposing the backlit foreground and the very bright Eclipse, compounded by the very high and far above the horizon apex timing at 10:35 MST. Finding a location for the foreground subject was incredibly difficult. Getting permission was incredibly difficult. Having no pre-run the day before made it incredibly difficult.

Camera Sony A7r3 Lens FE 4.5-5.6 100-400 GM

Filter -10 stop and -2 stop hand held and stacked (that is what caused the prism aberrations/lens flares) There is a reason that there are very few images with foreground subjects on this eclipse.

Support the Acoma People. Visit their pueblo, buy their beautiful ceramic pots, support their causes, and show them respect they deserve it.

[Pictures of New Mexico] :: [Rick Armstrong]

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

#photography#photographers on tumblr#my photos#35mm photography#35mm film#gallery#art print#new mexico#acoma pueblo#church#black & white

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Acoma Pueblo New Mexico, 1950s (2) (3) by David Redman

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I Went to my Territory

Joe Seymour Jr

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

@sixth-light you were right I love Mara of the Acoma & her meet-cute* with the local bandit leader she’s trying to recruit into her army by making herself bait. Incredible, showstopping, these are a few of my favorite things etc

*I’m just guessing, but I’m rooting for it because I am predictable

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Our Culture Is Woven Into the Land

Joe Wahalatsu? Seymour Jr. (Squaxin/Acoma Pueblo)

woven paper, synthetic sinew, framing. 32.35” x 37.75”

#weaving#joe seymour jr#wahalatsu?#joe wahalatsu? seymour jr#acoma pueblo#acoma#pueblo#squaxin#indigenous art#native art#first nations art#ndn art

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

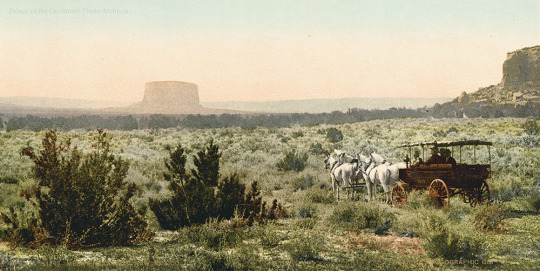

"Mesa Encantada, New Mexico"

Photographer: William Henry Jackson

Date: ca. 1899

Negative Number: 158668

511 notes

·

View notes

Text

«I love you» in different Native American languages

Qunukamken = I love you (Alutiiq Language, Alaska)

Chiholloli = I love you (Chickasaw, Oklahoma)

Ayóó’áníínísh’ní = I love you (Diné, Navajo, Arizona/New Mexico)

Moo ‘ams ni stinta = I love you (Klamath-Modoc, Oregon)

Ktaʔwãanin = I love you (Mahican Dialect, Stockbridge-Munsee Tribe of Wisconsin)

Konnorónhkwa = I love you (Mohawk, New York)

In ‘ee hetewise = I love you (Nimiipuutimpt, Nez Perce Tribe, Idaho)

Nu Soopeda U = I love you (Northern Paiute, Nevada)

Gizaagiin = I love you (Ojibwa/Bad River Ojibwe, Wisconsin)

Kunoluhkwa = I love you (Oneida Tribe, Wisconsin)

Thro sii muu = You are dear to me (Pueblo of Acoma, Acoma Keres dictionary, New Mexico)

Eee-peinoom = I love you (Pueblo of Isleta, New Mexico)

Amuu-thro-maa = I love you (Pueblo of Laguna, Laguna Keres dictionary, New Mexico)

Shro- tse-mah = I love you (Pueblo of San Felipe, San Felipe Keres dictionary, New Mexico)

‘Ho’doh’ee’cheht’mah = I love you (Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico)

Kʷ in̓x̣menč = I love you (Salish, Washington)

Gönóöhgwa’ = I love you (Seneca Tribe, New York)

Ixsixán = I love you (Tlingit, Alaska)

I daat axajóon — I’m dreaming of you (Tlingit, Alaska)

Ma ihkmahka — I love you (to a male) (Tunica, Tunica-Biloxi Tribe of Louisiana)

Hɛma ihkmahka — I love you (to a female) (Tunica, Tunica-Biloxi Tribe of Louisiana)

#Native American#NativeAmerican#Alutiiq#Chickasaw#Diné#Navajo#Klamath-Modoc#Mahican#Mohawk#Nimiipuutimpt#Paiute#Ojibwa#Ojibwe#Oneida#Acoma#PuebloofIsleta#PuebloofLaguna#PuebloofSanFelipe#PuebloofZuni#Salish#Seneca#Tlingit#Tunica#Love#Amor#foryou#parati#fyp#foryoupage

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mary Histia (1881-1973) an Acoma potter known for her large water vessels delicately painted with polychrome designs, photographed in 1900.

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

.

#also speaking of aus I personally have a special place for a rook lived but was in acoma for several years au#fjskdjsksjs#bc it allows Edith and Kiara to still be the same people who were fundementally changed by their mothers neglect#but also they get to have rook be there for events later in their lives#and Edith gets to have 4 dads wearing dads club shirts at her fight matches loll#but also not looking at the emotional turmoil that must be plaguing Rebecca and rook considering how she dealt w his absence and the way it#ruined her relationships w her daughters#fjskdjsksjs well actually I am looking bc that’s a v interesting thing for them to have to navigate lmao#anyway#rook acoma au is for when u want him to see his daughters be stupid ab love but also they need to still have the character development from#him dying#idek what Rebecca’s job is atm bc like Kiara nd Edith are only occasionally in way haven really atp#don’t think too hard ab it lol

6 notes

·

View notes